The Virginian’s Political Journeys

The 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s were the golden age of Western movies and television shows in the United States. In 1960, for instance, there were more than half a dozen major Hollywood Westerns released in theaters, including The Magnificent Seven, starring Yul Brynner (who later did an ominous parody of this role in 1973’s Westworld, which today, remade, has become a major hit for HBO), The Alamo, directed by and starring John Wayne, Flaming Star, starring Elvis Presley, and The Unforgiven, starring Burt Lancaster and Audrey Hepburn. There were also more than a dozen Westerns on television in 1960, including Gunsmoke, Wagon Train, Have Gun-Will Travel, Maverick, Rawhide, and Bonanza.

Why were there so many Westerns in this era? That’s a question I’ve been asking myself for decades, almost since I first started watching TV in the very late 1960s as a little California kid who was bewildered by the endless Westerns—and I almost always changed the channel when one came on. For many years I avoided Westerns, in part because they seemed politically right wing, and instead watched shows like Star Trek and The Twilight Zone. But over time I slowly realized that some Westerns are more complex than my youthful impressions led me to believe, and I’ve come to agree with George Lucas, who, influenced by Joseph Campbell, called Westerns an “American fairy tale, telling us about our values” 1.

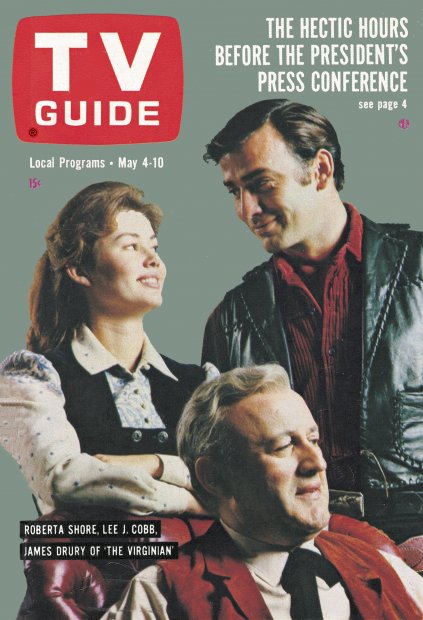

The Virginian, broadcast on NBC from 1962 to 1971, was in many ways the peak of the classic television Western—and was the most politically sophisticated. CBS’s huge hit Gunsmoke, which premiered in 1955, inspired a deluge of TV Westerns in the following years. But Gunsmoke—like several other Westerns in the late 1950s and early 1960s—was a low-budget, 30-minute, black-and-white show. In contrast, NBC promised in a press release at the launch of the The Virginian that it would be “the most ambitious and costly programming enterprise in network television history—one that will present television features with motion picture dimensions each week,” which would be “achieved not only by the ninety-minute length—which allows for full character development and expanded story-telling opportunities—but by color photography, location shooting, outstanding scripts and original musical scores” 2. And The Virginian came close to living up to this hype during its nine year-run of 249 episodes, each of which is like a little Western movie with continuing characters.

As Frank Price, an executive producer on the show, later wrote, “When we started on The Virginian, we didn’t know that producing a series of weekly 90-minute movies…was nearly impossible. So we managed to get the job done” 3.

There was real-life drama behind the scenes in network TV-land in early 1962 that created the expensive gamble that was The Virginian. At that time NBC’s top-rated show—and in fact the highest-rated show on all of American television—was the hour-long Wagon Train. (1962 was also the year that Gene Roddenberry made his first pitch for Star Trek, which he described in a way that he thought network executives could understand as “Wagon Train to the stars” —in other words, a Western in space.) But it was contract renewal time for Wagon Train, which had already had a very successful 5-year run, and at the beginning of 1962 ABC made a bold move and legally “stole” Wagon Train from NBC, by offering the producers of that show a better deal.

And so NBC lost their top show and top money-maker. NBC executives were mad, but more than that they were going to get even with ABC—no matter what the cost. And so directly opposite ABC’s time-slot for Wagon Train—which was already a fairly elaborate Western with more big guest stars and location photography than Gunsmoke (although still done in black and white)—NBC green-lit The Virginian in color directly to series, without even making a pilot. The Virginian was the most expensive show on television when it premiered on September 19th, 1962, with an average production budget per episode of $330,000, which is almost $3 million in today’s dollars 4. The only other color Western at the time was NBC’s Bonanza (in 1962 less than 3% of US households had a color TV), which had an average budget of $119,800 in 1962, about $1 million today. (Production costs for hour-long dramas in the 21st century range from about $1.5 million per episode for a show like Downton Abbey, to as much as $10 million per episode for the last seasons of Game of Thrones.)

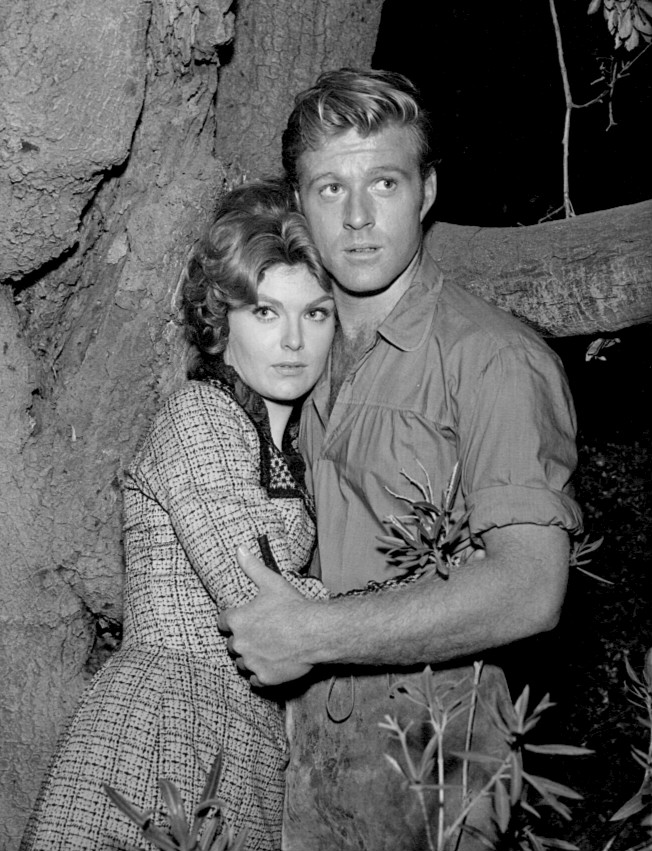

What did NBC get for its money? With its for-the-time lavish budget The Virginian could afford guest stars like Lee Marvin, Bette Davis, Ricardo Montalbán, Gena Rowlands, Robert Redford (who later said he used the $10,000 he was paid to buy his first land in Utah for what became his base for the Sundance Film Festival), Angie Dickinson, George C. Scott, Joan Crawford, and many others—including future Star Trek stars William Shatner, Leonard Nimoy, and DeForest Kelley. The show would also hire some of the best writers, directors, cinematographers, and composers. To give just one example from the last group, Bernard Herrmann, the composer of iconic scores for Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo and Psycho, was hired to compose scores for four episodes of The Virginian.

In addition to the deluxe production, The Virginian’s main cast had good chemistry from the start, and the show was able to beat Wagon Train in the ratings by a wide margin. In fact, in a few years Wagon Train was off the air. The improbable idea of making a TV series with “motion picture dimensions” had paid off—an idea that would be revived in our era of “peak TV.”

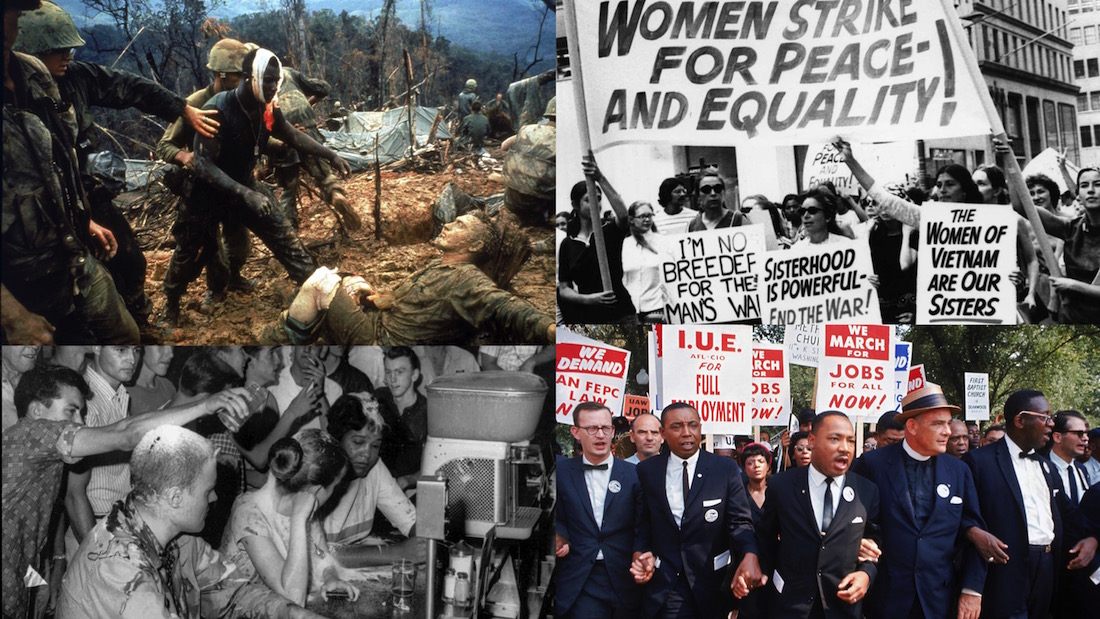

But the political transformation of the West in The Virginian was just as significant as its elaborate production values. The 1960s were, of course, a time of turmoil and political change, and The Virginian at times offered progressive explorations of class issues, the death penalty, Native American rights, and women’s rights.

One key to this political reimagining of the TV Western was the never-named Virginian, played by James Drury—a real-life cowboy who trained at New York University as a Shakespearian actor—as a thoughtful contrast to Western stereotypes. To get around from saying the character’s name he’s called “the Virginian,” “the foreman,” or other nick-names, but Drury thought this was a strength rather than a weakness, because it made the character “a man of mystery” 5.

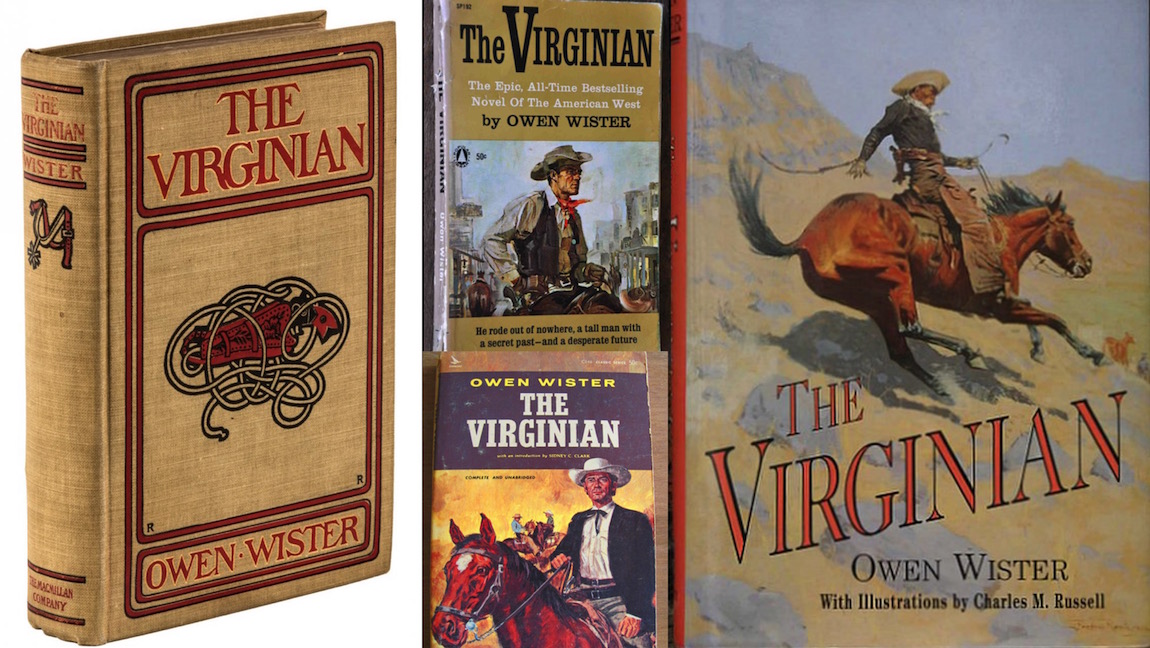

The Virginian TV show was loosely based on the famous novel of the same name by Owen Wister, published in 1902, where the Virginian’s name is also never revealed. Wister’s book, which sold steadily for decades—even into the 1960s—is considered by many the founding novel of the whole Western genre 6. The book is a weird mixture of love poem to the West, and specifically Wyoming, combined with a politically reactionary story—which in crucial ways was changed for the TV series.

The Virginian’s love of nature in the book comes through in the following passage, which anticipates more recent environmental ideas about being one with nature: “Often when I have camped here, it has made me want to become the ground, become the water, become the trees, mix with the whole thing. Not know myself from it. Never unmix again” 7.

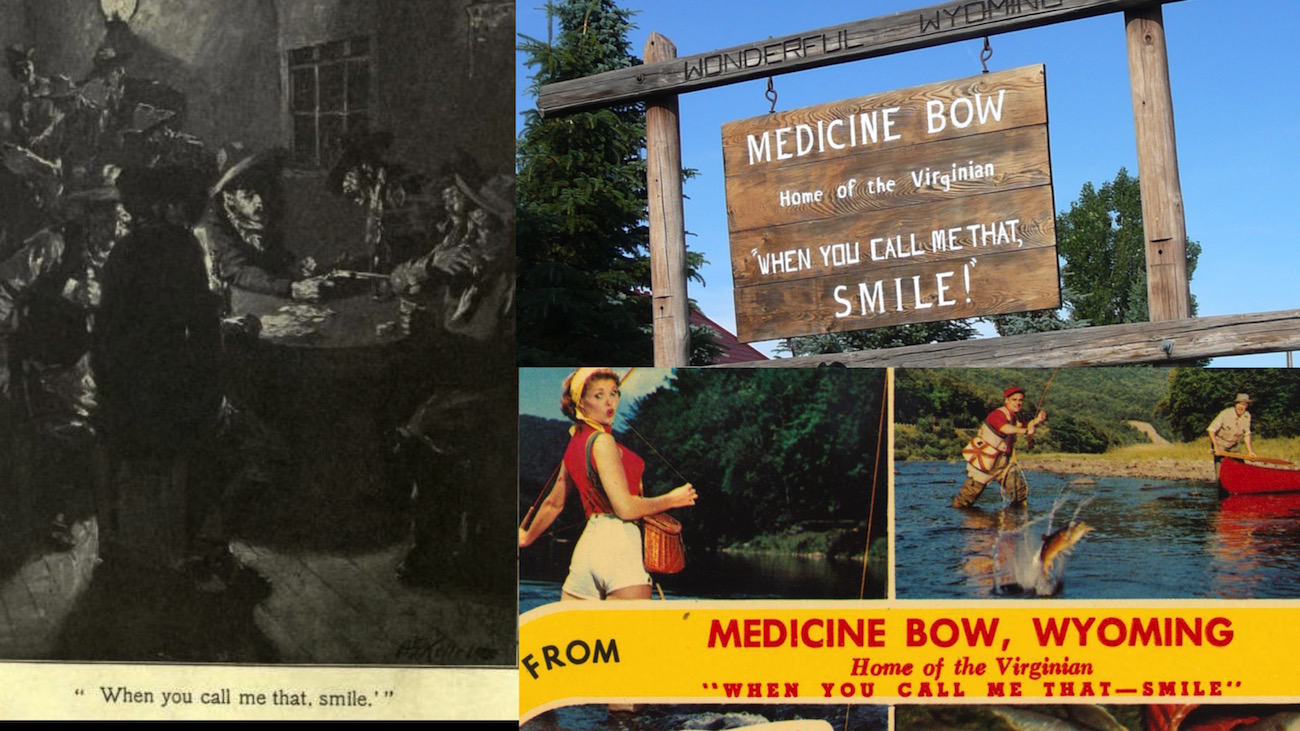

In the novel, the Virginian meets in the town of Medicine Bow, Wyoming, a no-good cowboy named Trampas. As the two of them play a high stakes game of poker, Trampas says to the Virginian, “Your bet, you son-of-a- –––––.” The Virginian cooly replies, “When you call me that, smile” 8. This became one of the most famous lines in Western fiction. It also became a tourist calling card for Wyoming, even found on highway signs, and was eventually included in an episode of the TV show.

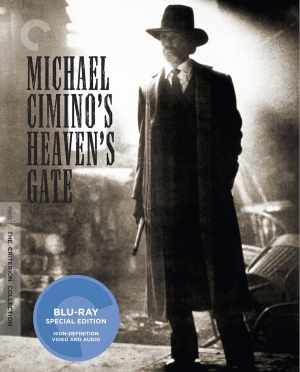

Wister was born in Philadelphia, and graduated from Harvard, but like his Harvard classmate and friend, President Theodore Roosevelt, he stayed for a considerable time on ranches in the West. Wister was often in Wyoming during the years of the Wyoming Range War, a series of hangings and gunfights between rich ranchers and poor homesteaders between 1889 and 1893. But while Michael Cimino’s epic 1980 movie Heaven’s Gate takes the side of the homesteaders, as have all recent historians, Wister’s novel instead takes the side of the well-off ranchers, and has the Virginian pitted against the alleged rustlers.

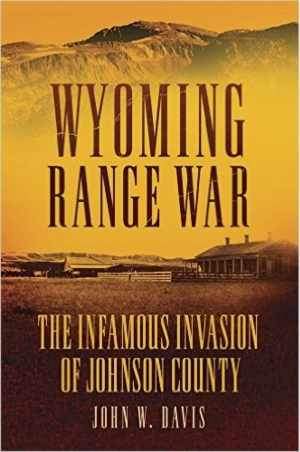

In the real Wyoming Range War, also called the Johnson County War, many alleged rustlers were killed on flimsy or no evidence. For instance, 29-year old homesteader Ella Watson was strung up from a tree in 1889, for supposedly branding a few stray cattle as her own. The monied ranchers, who formed the Wyoming Stock Growers Association (WSGA), manipulated the press after her death to portray Watson as a prostitute and cattle thief. The WSGA later hired 23 gunmen from Texas to terrorize and kill the homesteaders, leading to dozens of murders.

John Davis, in his book Wyoming Range War, writes that the conflict was part of the widening divide between rich and poor in late 19th century America, writing that “the Johnson County War was of a piece with the 1886 Haymarket riot, the 1892 Homestead strike, and the 1894 Pullman strike; they were all points of explosion stemming from deep conflicts permeating American Society” 9.

In the novel, the Virginian is the foreman for Judge Henry’s huge ranch, and takes the side of the rich ranchers, even making sure that his good friend Steve hangs for cattle rustling.

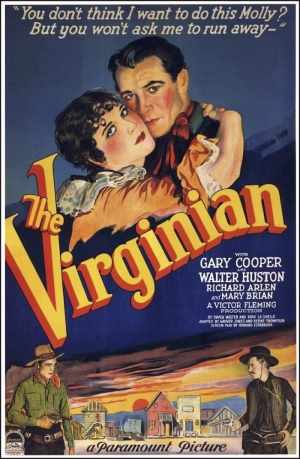

The most famous movie version of the story, the 1929 film that made young Gary Cooper a star in the title role, stays true to this tale—although somehow Cooper, through his tortured expression as his friend hangs, manages to keep the character sympathetic. The 1946 Technicolor remake of The Virginian, starring Joel McCrea, also stays true to the original plot. And in the 21st century there have been two additional movie versions of The Virginian—in 2000 a TV-movie starring Bill Pullman (who played the President in Independence Day), and in 2014 a theatrical feature with country-music star Trace Adkins in the starring role, both of which also stick fairly closely to the novel.

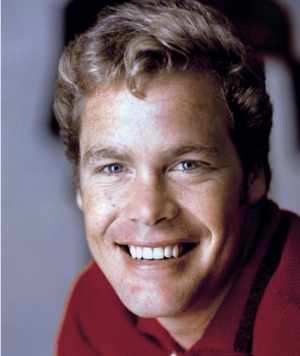

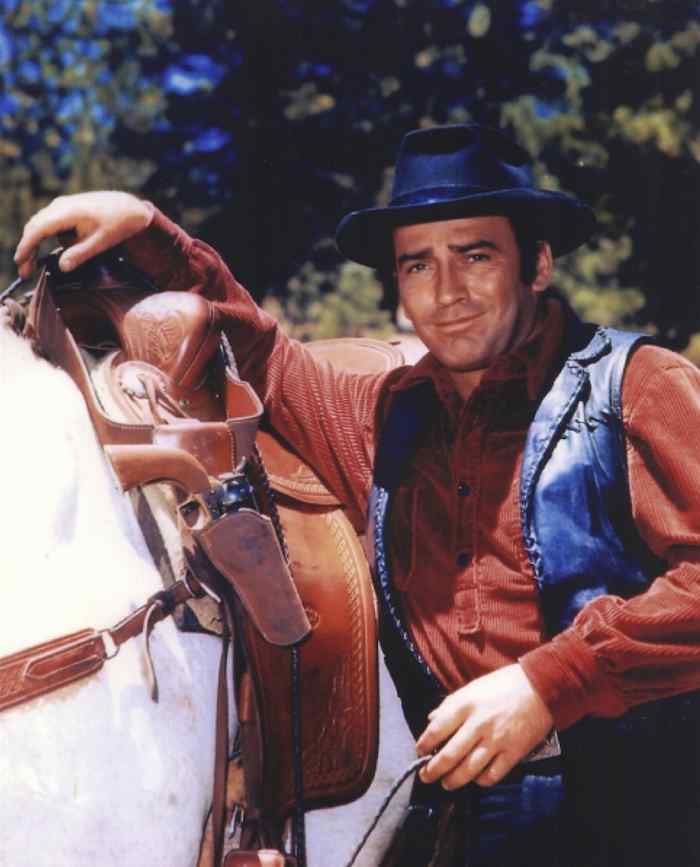

But when NBC decided to adapt the book for a series, the writers and producers made significant changes—all of which made the Virginian more sympathetic, and also made him, and the show, more politically progressive. Trampas, played by the charismatic Doug McClure, was transformed from a villain shot down by the Virginian into his best friend. Steve, played by Gary Clarke, stays a friend, rather than being a rustler hung from a rope. And the romantic interest in the novel, Molly Wood, played by Pippa Scott, gets a career as the owner and reporter of the local newspaper, the Medicine Bow Banner.

And the Virginian’s role in the Wyoming Range Wars is also changed in a key episode of the first season, called “Throw a Long Rope.” This episode gets its title from a saying from Wyoming’s territory days: “Throw a long rope over a tall tree, and hang the rustler till dead.”

To a montage of film clips, the Virginian sets the stage in a voiceover that is almost unique among Western TV shows of this era in its attempt to summarize and analyze real history:

Virginia. I was born here. It’s peaceful, beautiful. And a long, long way from Wyoming. Beautiful too in its special way. Vast, proud, and lonely. It’s my country now, Wyoming, but not exactly a peaceful one. It had happened before, in New Mexico where over a hundred men were killed in 1878. In Montana, where scores more died only a few years later. And now it was happening in Wyoming: Range War. The stakes were always the same: cattle and land. And the opponents were always the same: big ranchers versus farmers seeking open range to settle on under the Homestead Act. The cattleman who came first and carved his vast rangeland out of the wilderness saw himself facing destruction, as the homesteaders settled on his range, fencing him off from the grass and the water. The homesteader had many names in the West—squatter, nester, and sometimes with truth, rustler. The cattlemen struck back, fast and hard.

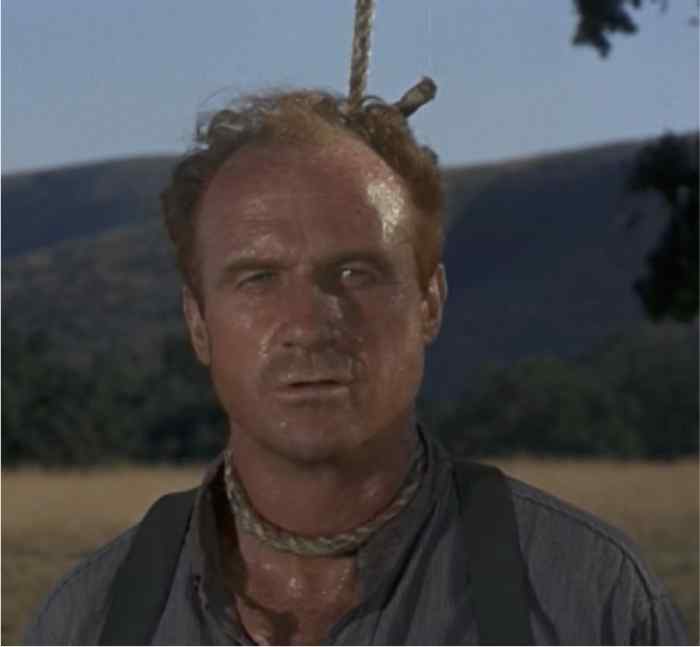

And that’s what we see at the start of the episode, as guest star Jack Warden, playing homesteader Jubal Tatum, who is accused of cattle rustling, is strung up by a rope from a tree by ranchers, with a horse-drawn wagon underneath. The monied ranchers include the Virginian’s boss, Judge Henry Garth, played by distinguished actor Lee J. Cobb (who was nominated for an Oscar for his role in On the Waterfront).

Jubal says, “I’m no thief….You’re murderers. Every last one of you: murderers.”

Jubal is including in this accusation the Virginian, who looks on with a pained expression. The Virginian then demands that the calf Jubal is accused of stealing be allowed to pick its own mother. And when the calf picks Jubal’s cow, seemingly he’s saved from the noose. But then Jubal’s young son runs up, and, trying to save his father, blasts a shotgun. This spooks the horse attached to the wagon, and the Virginian and Steve are barely able to cut Jubal down in time, and he’s left with a broken leg and a rope-burned neck.

It’s a shocking beginning, especially for just the third episode of the show, because it makes viewers think that the show’s supposed heroes, the Judge and maybe even the Virginian, are on the wrong side, and maybe even potential murderers. But the Virginian quickly decides he wants no more of it. He wants to keep his job, but decides he has to do what’s right, and tries to convince the Judge. But Garth still thinks Jubal is guilty, even if that particular calf was in fact his, and says that hanging rustlers is allowed under Wyoming law. The Virginian angrily replies to his boss, “Then the law legalizes murder!”

Some classic television Westerns often have characters who are binary, either good or evil. But in part to effectively fill the 90-minute time-slot of The Virginian (and actually each episode is 75 minutes long without the commercials), many characters on The Virginian are more complex and ambiguous. This is especially true for the characters played by many of the guest stars, but even continuing main characters like Judge Garth, Trampas, and even the Virginian himself once-in-a-while make significant mistakes, or have flaws, as in this episode.

But the Virginian quickly recognizes his mistake (unlike Judge Garth), and tries to help. Since Jubal is too injured to work his farm, and so faces ruin, the Virginian strips down from his Sunday best to his bare chest to set posts for a fence for Jubal, and to plow his family’s land.

And looking at this image with the bare chest of the then 28-year old star, we can try to make an observation about the audience for The Virginian—as well as some other TV Westerns. The Virginian’s most important creator and executive producer, Frank Price, put it this way, “I believed women controlled the television set dial. This was before multiple sets and remote controls. So I tried to do stories that would appeal to that vast women’s audience. If women wanted to watch the show, the men would agree” 10.

Part of how The Virginian did this was by often having strong women characters in the main cast, and especially as guest stars. The show also had women behind the scenes as writers, some of whom wrote feminist teleplays—one of which we’ll look at shortly. And, of course, many women like Westerns for the same reasons that many men like Westerns—action-adventure in the mythological West.

But part of the show’s appeal for some women, as some women who are long-time fans of The Virginian have have told me, was also that it had a number of handsome and sympathetic single men beyond the title character, including the already mentioned Trampas and Steve, as well as Sheriff Emmett Ryker (played by part-Cherokee actor Clu Gulager), Randy Benton (played by Randy Boone), and others. And once in a-while scenes such as of the men in the bunkhouse taking baths, would allow for the display of handsome bare-chested men in a way that otherwise was not seen on TV at the time—which has also been mentioned to me by some women who are fans of the show. The Virginian would also, of course, often have beautiful women as guest stars—but the men in the show were sometimes even more on display as a spectacle.

(And The Virginian, of course, was not the only Hollywood example of displaying handsome men as spectacles, which is something that’s been present throughout film and TV history. A perceptive analysis of this in the previous decade is found in the book Masked Men: Masculinity in the Movies in the Fifties, by Steve Cohan. Or, as Anna North writes in her recent analysis of the new Wonder Woman movie for the New York Times, “Especially in his (very tame) nude scene, Mr. Pine is working in a mode previously explored by Chris Hemsworth in “Ghostbusters” and Channing Tatum in pretty much everything — the preternaturally attractive man who wears his beauty lightly….[E]ven the acknowledgement that male bodies can be beautiful sometimes feels subversive….[and] is a welcome break from a culture that frequently lays the heavy burden of hotness exclusively on women.”)

Getting back to “Throw a Long Rope,” the Virginian, after he gets his shirt back on, becomes a detective, taking off for a two-week trip in the high country of the vast Shiloh ranch, and then beyond, to find out if the accusations of cattle rustling against the homesteaders are true. He’s on the trail of Sweede Torgenson, who was already hired by the ranchers to find out where some of the cattle have disappeared to. On his journey, the Virginian runs into eccentric and difficult characters, but finally finds the cattle, who have been stolen by rustlers, not by the homesteaders. He also finds the body of Sweede—shot in the back by the rustlers.

The Virginian wraps up and carries the body back to Judge Garth’s very large ranch house, and then has it out with the Judge and the leader of the rich ranchers, Major Cass, played by John Anderson. Just as in the real Range War, the battle is in part one of propaganda played out through the newspapers, with the Major showing the Judge fabricated headlines (an example of how “fake news” is not new) to justify the brutal slaughter of the homesteaders.

The Virginian says, “You’d better tell that army outside to go home, Major. Bushwacking the homesteaders isn’t going to fix anything….The trouble’s on the other side of the hill—a rustler gang.”

When the Major sticks to his guns, the Virginian says to the Judge, “How long are you going to let this strutting Napoleon trade on your name….Why don’t you admit it, Major—You ran out of wars since the Wounded Knee fight. No more Indians to slaughter, no more cavalry charges. No more wars, so you gotta make one!”

This teleplay by Harold Swanton completely rewrites the approach to the Wyoming Range War found in Wister’s novel, becoming instead a critique of not just the rich ranchers and their war, but even of the slaughter of Native Americans during the settling of the West by whites—at Wounded Knee and elsewhere. And the Virginian risks his life to stick with the homesteaders to the very end.

The Virginian was also more progressive than almost all other TV Westerns of the time in its portrayal of women. Viewers of Bonanza know that a woman falling for one of the Cartwrights was taking an awful chance. The Cartwright curse began in the first season, when the first woman Michael Landon’s Little Joe falls in love with, as one Bonanza fan described it to me, “gets shishkababbed with a pitch fork thrown by James Coburn.” In “Inger, My Love,” Lorne Green’s Ben falls for Inger Stevens, who is killed by an Indian arrow; in “Erin,” Dan Blocker’s Hoss falls for the Indian-raised title character, killed by racist violence; and in “The Sisters,” Pernell Robert’s Adam falls for one of the sisters—and she dies. There are so many more examples that in truth Bonanza is family-friendly fatal attraction.

Of course, keeping the romantic possibilities open for the main characters was also a big part of The Virginian. But more often than not the women he fell for, and who also fell for him, would get their own happy ending, rather than a death sentence.

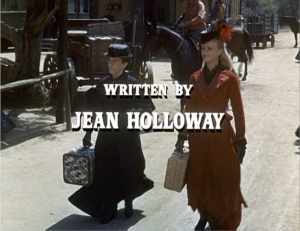

“All Nice and Legal,” for instance, stars Anne Francis as Victoria Greenly, a lawyer from back East who moves to Medicine Bow because she found out that Wyoming has the fewest number of attorneys per capita. This episode was written by Jean Holloway, one of a few women who wrote for the show. Producer Price said that Holloway was a “reliable and outstanding” writer, adding that “Jean wrote very strong women” 11. Holloway wrote six episodes for the show.

In this one, Victoria’s late father was a famous lawyer in Philadelphia, but she doesn’t want to trade on his name to make her career. Victoria’s chaperone, played by Ellen Corby, later Grandma on The Waltons, complains as they walk down Medicine Bow’s dusty main street that Victoria should have married one of her suitors back East. But Victoria is in no rush to marry because she wants to launch her career, and says that the way she feels now she might only marry if she could find a man who is “nine feet tall.”

And just then she bumps into the Virginian riding his white horse, and as she looks up at him he seems about nine feet tall. She clearly likes what she sees, and says humorously to herself after they’ve met, “You have to watch what you say in Wyoming.”

Victoria finds a good office to rent for her law practice, and since it’s owned by Judge Garth, the next day she travels to Shiloh and ends up talking again with the Virginian, but this time she doesn’t get a good impression. When he finds out she’s a lawyer he’s surprised, and asks if she’ll be relying on her legal fees to pay the rent.

The Virginian says, “Out here most law cases are between men. It might be hard for a man to think about hiring a woman to fight for him.”

She replies, “A legal fight is one with brains, not brawn. Or don’t you concede that a woman can have a brain?”

“Of course you have a brain,” he answers.

“You just don’t think I should be allowed to use it. Is that it?” She says.

After Victoria coldly takes her leave, the Judge’s daughter, Betsy, played by Roberta Shore, says to the Virginian, “Don’t tell me you’re one of those men who think the woman’s place is in the home?”

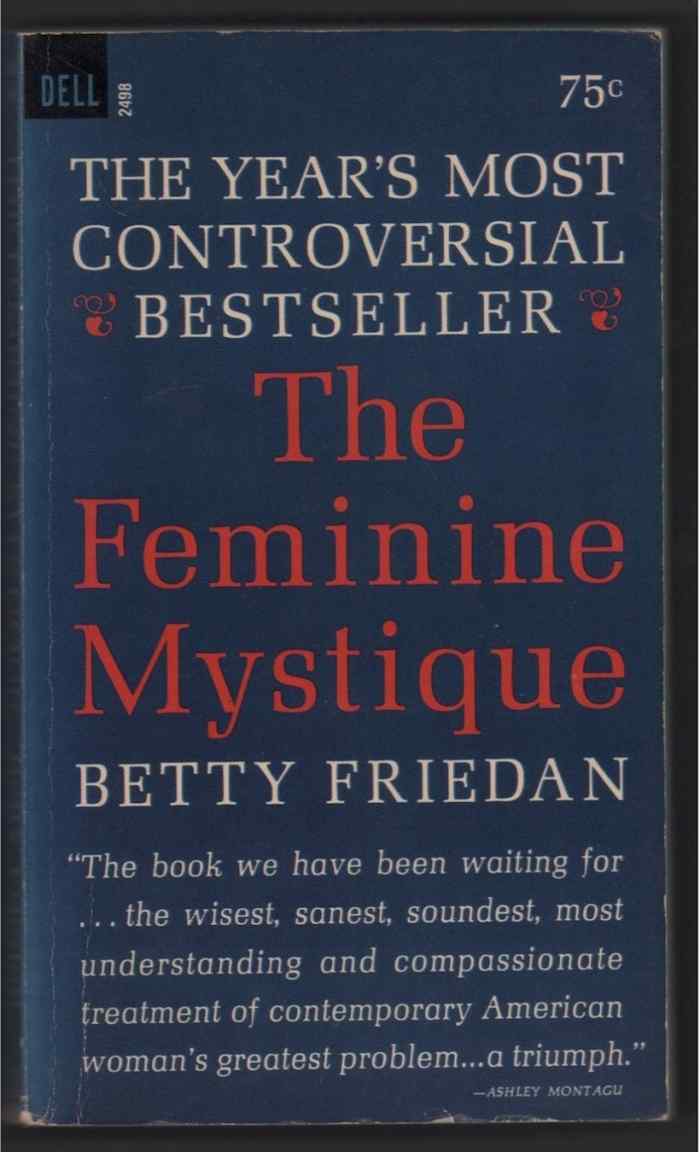

This episode was broadcast in 1964, just as the second wave of feminism in the United States was getting going, launched in part by Betty Friedan’s landmark 1963 book The Feminine Mystique. Friedan, like teleplay writer Holloway in this episode, challenged the widely-held belief that “fulfillment as a woman had only one definition for American women…[as] the housewife-mother” 12. TV Westerns don’t frequently provide progressive examples of gender roles, but with this episode The Virginian was on the cutting-edge of social change.

Betsy adds that she thinks her father, who’s away, would rent the office to Victoria because, unlike the Virginian, “He’s not old fashioned.”

The next day the Virginian sincerely apologizes to Victoria, and says that if she has references, and the price suits her, he’d be very happy to rent her the place. They make up and soon even start flirting a little, and eventually he invites her out for dinner. But just then the Virginian is served by Sheriff Ryker with a summons because of a dispute about a saddle he bought.

The Virginian explains to Victoria that he returned the saddle because it was improperly made, and was slipping off of his horse when he was doing hard roping work. She asks if he needs a lawyer, but he says he doesn’t need one as long as he tells the truth.

Victoria replies, “I’m afraid the law isn’t that simple.”

“It is when you keep lawyers out of it!” he says, confidently.

In court, the saddle maker has a very able lawyer who conducts a devastating questioning of the Virginian, who is argumentative and tongue-tied, all of which is observed by Victoria from the courtroom gallery. It’s clear he’s going to lose. The Virginian goes back to her office during the recess, and, having learned another lesson, asks if he can still hire her.

She says, “On one condition: you place yourself entirely in my hands”—which is obviously a reversal of how things often work in TV Westerns.

He agrees, but adds, “Do you know anything at all about saddles?”

“No,” she says, “But I will when I go into court.”

She gets a continuance to prepare the case, and then begins a journey with the Virginian around Shiloh to learn about the world of saddles and cowboys. She’d dedicated to learning, and this helps demonstrate that lawyers, like cowboys, gain knowledge and ability through study and practice—they aren’t born with it. And while she’s learning about saddles, they’re also learning about each other.

Victoria wins the case, articulately proving in court that the saddle was improperly made for its intended purpose. And the Virginian’s admiration for her intellect and other qualities is clear.

Soon her reputation as a lawyer spreads, and the courtroom gallery is often filled with people who’ve come to hear her eloquent arguments. The summation below by Attorney-At-Law Greenly is heard by the top aide to Wyoming’s governor, and it is perhaps the most convincing defense of the rule of law ever heard in the usually gun-happy genre of the Western:

Laws are established as rules of conduct—for civilized people. And civilized people must fight for the law, whenever it needs defending. A man who picks up a gun and goes after a suspected thief is answering possible robbery with potential murder. He’s compounding lawlessness….He would judge his fellow man with rage in his heart, and a gun in his hand. And a gun or a fist fight doesn’t prove who was right—only who’s strong. Here is where men with grievances must come… Here—in a court of law. Where both sides will be heard…This is the civil process, for civilized people. And it must be upheld. I’m here to plead for a man. But I also must plead for the law.

The Governor’s aide soon offers Victoria a job on the Governor’s legal staff in Cheyenne, just as she and the Virginian are falling in love, and even talking about marriage. Victoria is torn, but finally decides to take the job, and the Virginian wistfully says goodbye to her at the train station.

When Victoria wonders aloud if she should stay, the Virginian thoughtfully says, “Remember what you said the other night: When one woman takes a step forward all women benefit. I think you meant it.”

They kiss passionately, and part on good terms. Needless to say, there’s a big difference between this and the Cartwright kiss of death. As Sue Matheson writes in her book Love in Western Film and Television, “portrayals of love in Westerns have reflected the changing nature of relationships between men and women” (p.3). And this was particularly true during the 1960s, as “Americans experienced an exodus of women from hearth and home to the workplace” (p.4). “All Nice and Legal” sensitively portrays the challenges of trying to find fulfillment in both work and in love, and respects Victoria for choosing work even over the Virginian.

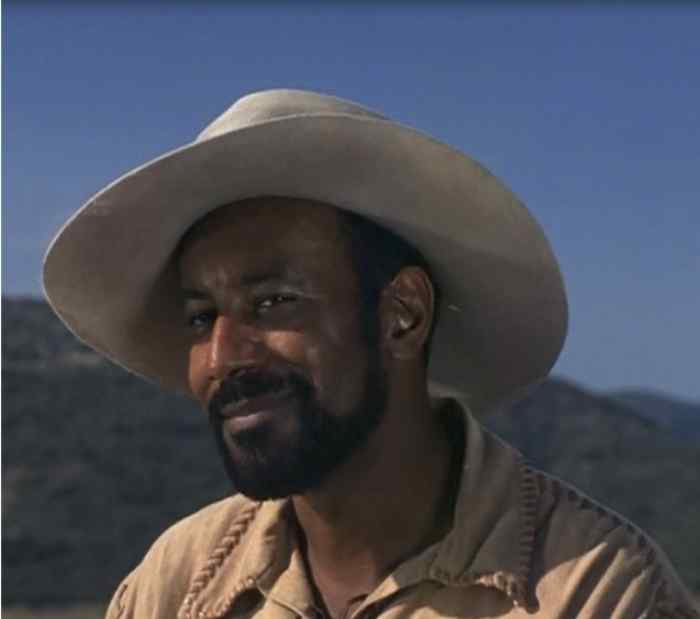

I’ll admit that I’ve carefully selected these two particular episodes to analyze, and many episodes of The Virginian are closer to traditional TV Westerns of the time. But there are many other episodes that could also serve as examples of the progressive tendencies of the show, including a 1968 episode titled “The Heritage,” starring Buffy Sainte-Marie, which was apparently the first Western TV show or even movie to cast all Native Americans in Indian roles. There are also episodes that question the death penalty (including “The Executioners”) as well as episodes that have prominent roles for African Americans (such as Raymond Saint Jacques, who was one of the guest-stars in “Trail to Ashley Mountain”). And behind the camera not only did women sometimes write for the show, but actress and director Ida Lupino directed a notable episode titled “Dead-Eye Dick” in 1966.

Why was The Virginian more complex and progressive than most other TV Westerns? Part of the answer is that star James Drury and producer Frank Price had high ambitions for the show. As the now 83-year old Drury said in a recent interview, “I attribute the success of The Virginian to its 90-minute format, which allowed our writers to write big, important, juicy, meaty guest star roles for men and women. Actors will walk barefoot over broken glass to play roles that they want to play.” Or, as Price explained, “One of my maxims to all was that our goal was to make our shows for the critical ten percent of the audience. Ninety percent of the audience will be entertained by almost anything you do—if they like the actors and the concept of the series. But ten percent have a higher threshold of approval. And those were the people we were trying to please. We didn’t always succeed, but we were always trying” 13.

The Virginian remained relevant and got good ratings throughout the turbulent 1960s, even as most other TV Westerns launched in that decade had relatively short life spans. And it transformed a book and a character shown by extensive analysis by historians Richard Slotkin and Jane Tompkins to be racist, Social Darwinian, sexist, and even anti-democratic 14, into television narratives that are often progressive, and once-in-a-while even liberal. The Virginian a liberal? To some “liberal” might be almost a curse word—and so if you ever call him that, smile.

Works Cited

- Stephen and Robin Larsen, Joseph Campbell: A Fire in the Mind, Doubleday, 1991, p.541. ↩

- Gary A. Yoggy, Riding the Video Range: The Rise and Fall of the Western on Television, McFarland, 1995, p.395. ↩

- Paul Green, A History of Television’s The Virginian, 1962-1971, McFarland, 2006, p.4 ↩

- Paul Green, A History of Television’s The Virginian, 1962-1971, McFarland, 2006, p.99 ↩

- Paul Green, A History of Television’s The Virginian, 1962-1971, McFarland, 2006. p.97 ↩

- Edward Buscombe, Editor, The BFI Companion to the Western, Atheneum, 1988, p.18; Richard Slotkin, Gunfighter Nation: The Myth of the Frontier in Twentieth-Century America, University of Oklahoma Press, 1998, p.175-183; Jane Tompkins, West of Everything: The Inner Life of Westerns, Oxford University Press, 1993, 131-157 ↩

- Owen Wister, The Virginian: A Horseman of the Plains, Dover, 2006, p.287 ↩

- Owen Wister, The Virginian: A Horseman of the Plains, Dover, 2006, p.17 ↩

- John W. Davis, Wyoming Range War: The Infamous Invasion of Johnson County, University of Oklahoma Press, 2012, p.xv-xvi ↩

- Paul Green, A History of Television’s The Virginian, 1962-1971, McFarland, 2006, p.42 ↩

- Paul Green, A History of Television’s The Virginian, 1962-1971, McFarland, 2006, p.3 ↩

- Betty Friedan, The Feminine Mystique, W.W. Norton, 1963, p.xi-xx ↩

- Paul Green, A History of Television’s The Virginian, 1962-1971, McFarland, 2006, p.58-59 ↩

- Richard Slotkin, Gunfighter Nation: The Myth of the Frontier in Twentieth-Century America, University of Oklahoma Press, 1998, p.170-175; Jane Tompkins, West of Everything: The Inner Life of Westerns, Oxford University Press, 1993, 131-157 ↩

What do you think? Leave a comment.

I haven’t watched any of it, but I appreciate content were various sensitive topics are handled in a real-to-life manner.

Wish British tv would rerun some of the great old westerns again I would love to watch the Virginian.

I grew up watching all of these Western series. They were all very popular on the BBC and ITV. I don’t understand why they are ignored today in the UK. Since moving to America I’ve been fortunate to see many classic Western shows again on cable TV over here. They are still entertaining and make a pleasant change from the numerous forensic crime shows that are popular today.

During the 1960s and 1970s we tended to see a lot of American shows in prime-time in Britain, but that changed in the 1980s.

As a writer, “The Virginian” helped give me my start. And still writing after all these years I’m not sure whether to thank the producers or not. I do recall, however, with much pride and joy, meeting with the Producer and pitching my story. And more important his telling me he liked it, and asking the name of my agent. It was a different day. Like the o’ west…a better day.

Thanks for writing this article and I’m looking forward to reading it later tonight when I am back home from work. This is one of my all time favorite TV shows.

I learned so much from this article. A topic that deserves to be remembered.

Great Article! Love the show and James Drury!

What a well written love letter(my words)to this gem of a show. As a child I don’t remember watching it that often. My taste as well leaned more toward Little Joe & Bonanza and the Sci-Fi series you mentioned. But now not only am I a proud member of a Facebook group that honors the show but I own most of the series! Great work in front of and behind the camera that I really couldn’t appreciate as a child. Thanks for this grand article Benjamin.

The Virginian’s episodes tell stories that are timeless. The battle of good and evil. Quality cast members and guest stars. It doesn’t get any better.

So much nostalgia! I would watch every episode again, and with great enjoyment!

I think this show was overshadowed by the more famous and popular shows of the time.

Never heard about it, but better late than never when it comes to watching The Virginian I suppose.

I love westerns & have read over 100 of louis lamoure books. they are feel good books! I enjoyed the time in the u.s.a. 1930’s & 40’s’. people were very close & built poches in front of their homes instead of decks in the backyard with fences. this is the feeling i get watching this series.

From my memories of the show, female characters generally stood up for themselves – unless ‘their man’ told them to shut up and act all lady like.

It was my favourite TV western when I was a child, and I believe it was much more superior than the other TV westerns of the 70s.

The life lessons we learned in this show are still with us.

Love The Virginian but I also loved Cimarron Strip.

I wasn’t a big fan of “Cimarron Strip” Bethel. I watched episodes again a few years ago but have never cared for Stuart Whitman in the lead. Randy Boone was under-used compared to his work on “The Virginian.”

My son in law just set up Tivo so I can record all of The Virginian Series on the TV and watch them when ever I want to. Save the episodes you want and erase the others. Not very expensive and better then the China DVDs and cheaper then buying the authorized DVDs

The more I learn about it, the more I fall in love with The Virginian.

The Virginian was more historically accurate than many TV Westerns of the 1960s.

Terrific and very detailed analysis. Thank you.

Used to love this show – esp. the theme music! The 60s had some great TV theme music, esp. westerns.

As a kid I was madly in love with James Drury.

used to show it on TG4 in Ireland a few years ago, used to have little clips of an interview with James Drury before the show (AFAIR)

quality bit of television!

The Virginian was my first tv hero, even before Captain Kirk. He always wore a black hat, even though he was a goodie, and a party was always called ‘a celebration’ (sigh).

Doug McClure went on to be an action hero, and, as I remember, Clu Galager went on to be a baddie in every tv detective show in America!

The Virginian is a very positive series with great moral values.

Westerns is the genre I like best.

I’m not a big Western fan, but appreciated your thorough analysis of The Virginian, especially the roles of women in the show. I see great compare/contrast potential between this and other, more “politically traditional” Westerns such as, say, Little House on the Prairie or Bonanza.

Color TV coming along in the 1960s. We could go to a store front and watch Bonanza through the store window to see what color TV was like–obviously a way to get people to come in an buy a color TV. For years, Bonanza was thought of as the selling point for buying a color TV. I remember going with my parents on a Sunday evening to stand in front of a store window, along with other families. We probably did not stay for an entire show, I don’t remember sound, just the picture.

I love the West, grew up there but was 80 years late! My family were all cattle and horse folks. I am 75 and still have steers! The Virginan makes me happy and isn’t just a gunfight or misery. I had to stop watching Wagon Train because of the weekly suffering. I was living in dust storms and praying for rain myself!

Thank you for writing a very insightful piece about The Virginian. I consider mutton be one of the 10%. The story lines, character development, costumes, musical score lead the viewer to look at the moral aspects of life. Challenges faced today are called to question 50 years ago. Great acting and always a little quirky humor. Randy Boone’s singing is a pleasant diversion from the story lines and much appreciated. There are times when watching this show I c an close my eyes and listen to the dialogue, it’s as if someone is reading a good book to me. It’s nice to know others appreciate the work which went into producing a great series