Theatre Beyond the Ground: Staging a Defiance of Gravity from Aeschylus to Živadinov

Near the beginning of Edward Gordon Craig’s famous treatise, On the Art of the Theatre, he describes the all too familiar dilemma of a young theatre enthusiast trying to explain to their parents why they want to devote their lives to the stage. He says:

you could give no reasonable answer because you wanted to do that which no reasonable answer could explain; in other words, you wanted to fly. There you got your answer. It’s an inconcrete and ambiguous answer but so is the theatre. Basically you want to fly, but you’re unable to. Hence ‘theatre’ for me is ultimately an endeavour to make something impossible possible; a rebellion against our inability and our human limitation (Craig, 2).

Though his use of the term “I want to fly” is clearly meant to be metaphorical, there is a long tradition of theatrical endeavours that have aimed precisely at literalizing statements of this kind. For practically as long as theatre has existed, attempts have been made to use it as an magical means to defy our worldly limitations, gravity being one of them.

For most of human history, this illusion has been created with this use of some variation of what is called a “fly system” (sometimes referred to as a “rigging system”). It is, by definition, a simple machine; by attaching one end of a specially-designed pulley mechanism to the actor and having a member of the backstage crew act as a counterbalance by pulling on the other end, the performer can be lifted up off of the ground and appear as if he or she is flying. Though centuries would be spent re-designing this system with the hopes of eventually arriving at the best possible mousetrap, it was not until the 1980s that newer – and more technologically sophisticated – methods would come along to do away with the ropes and wires altogether (to be discussed below). From the ancient Greek tragedies to the biblical cycle dramas of medieval England, the debut production of Peter Pan to contemporary Broadway musicals, all the way to revolutionary “postgravity” theatre of Slovene director Dragan Živadinov, attempts to implement y-axis mobility to the stage have been historically integral to the on-going process of innovation in the aesthetics of performance and spectacle.

The Original Deus Ex Machina

To begin this examination into the use of fly-type systems in theatre, it is beneficial to begin with the birth of the western theatre itself, in ancient Athens. It is often difficult to appreciate the extent to which the Greeks employed intricate staging technology, considering that, at that time, it was enough of a marvel for audiences to see people playing characters other than themselves in a larger-than-life narrative performance. In Aristotle’s Poetics, he counts “spectacle” as one of his six constituent elements for tragedy, but hierarchically last among them. Of it, he says that, “spectacle, while quite appealing, is the most inartistic and has the least affinity with poetry […] for achieving the effects of spectacle, the art of the mechanic of stage properties is more competent than the art of poetry” (Aristotle, 15). Even if he was not overly fond of spectacle’s contribution to the tapestry of theatre – keeping in mind that he was focusing his study primarily on the poetic elements of tragedy, which was rooted in the oral tradition first and foremost – he still acknowledged it as a noteworthy part of dramatic staging. His observations of spectacle act as an indication of the importance of it to the ancient practitioners and audiences, which made it such a pervasive ingredient of early drama.

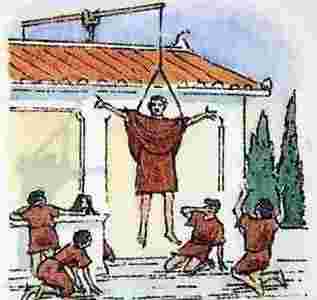

The manner in which the Greeks employed rigging in their spectacles was through their recurring motif of bringing the gods onto the stage as a symbolic presence of divinity that manifests physically to interact with the human characters. Examples of this can be found in the some plays of Aeschylus (The Eumenides, The Suppliants, Prometheus Bound), Euripides (The Bacchae, Hippolytus, Iphigenia in Tauris), and Aristophanes (The Frogs, Thesmophoriazusae). None of the seven surviving plays of Sophocles employed this device; it consequently cannot be known if he ever dabbled with it in his works that have since been lost.

In order to visually differentiate these immortal characters from the earthbound mortals, these god characters would be lowered down into the playing area by a crane-like “machina” (the Greek word for machine). There is a lovely fictionalized depiction of ancient thespians using the machina in Mary Renault’s 1966 historical novel, The Mask of Apollo. In Chapter II, we get the description, “The music rose to cover the creak of the machine; the rope at my back was taut. I grasped my silver bow, and leaned on the harness in the arc of flight. Up I soared, out above the skene” (Renault, 43). Shortly after, the true limits of this technology are shown, when the rope nearly snaps under the actor’s weight during a performance.

This technical innovation is now best known for having spawned the term “deus ex machina”, which translates to “god of the machine”. The phrase has entered common usage today as a literary device to define an instance in which characters are saved from a difficult scenario by an external – and often omnipotent – force. This was frequently the context wherein the gods appeared in the Greek plays to necessitate their entrance by means of the machina. It is typically given a negative connotation, often when authors are seen as too lazy or unimaginative to think of an actual solution to the conflict that they have established.

The presence of the gods played a very important role to the religious significance of early tragedy. For the ancient Athenians, theatre-going was not the recreational experience that it is today; it was a religious ritual and a social duty in which all of the men of that society were obliged to participate, mainly at the annual Festival Dionysia. The act of experiencing catharsis had a special spiritual impact that we have long since veered away from, and coming face-to-face with the otherwise invisible deities may have created an additional level of divine exuberance. Seeing these beings fly no doubted contributed greatly to the sublimity of the godlike presence wielded by the characters as they entered from a space that was closer to the heavens than the mortal spectators could ever imagine a man could go.

The Big Man Upstairs

Many centuries later, western civilization underwent a great many changes as everything began to shift from poly to monotheism, characterizing the medieval era; the desire to represent invisible deities in the visible realm of theatre, however, was not one of them. Much like their ancient Greek predecessors, the theatre practitioners of medieval England were mainly concerned with using the stage as a vehicle for the propagation of their religious mythology. The Christian church, however, took “vehicle” literally, leading to the popular cycles of pageant dramas for the sake of performing biblical parables (typically known as “Mystery Plays”) in a parade of wagons with platform stages through the streets of York, Wakefield, and Chester, among others. Having predominantly taken place before the translation of the Bible into English – and taking into consideration the mass illiteracy among the populace under a feudal regime – these plays acted as the most accessible means of conveying the Bible’s content to the general public.

Though we have many sources which suggest that pulleys were still used in these plays when angel characters appeared (Davidson, 30), a different method was often employed when the character of God – no longer one of many, and therefore needing a special position to connote His importance – took the stage. As Katie Normington recounts in her book, Medieval English Drama, “It is clear that the wagon had two stories, one served as a general acting area and the other, symbolized by decorative angels, represented heaven and was used only by God” (Normington, 69).

By placing the God character of these plays in this physical hierarchy over all others, His tremendous might and supremacy is presented to the audience in a starkly visual manner. This structure of having him exist beyond the world of mankind stays true to the Judeo-Christian mythos, in which God is omnipresent, but seldom interacts directly with man. That said, the framework of the wagons could be interpreted as a microcosm for the spectators’ real lives under that system of beliefs, in which the human characters cannot see God, but he is present and looking down in judgement. Staging this metaphor for Christian metaphysical beliefs is an extension of the Greek model without the need of fragile ropes and wires. This God does not need to “fly” to assert His existence on a higher plain.

The theatre of the Early Modern period that followed saw a decline in the depictions of God onstage, and the theatre itself began to increase in popularity as something greater than a religious propaganda machine. Further technical innovations in the field of stagecraft arose by the time that Shakespeare entered the scene, allowing many of his more supernatural characters – such as Puck, Ariel, and the Witches – to fly with similar pulley systems that were built directly into the Globe Theatre’s architecture. Additionally, some of his less magical, but still fantastical, plays (among them Hamlet, Julius Caesar, and Richard III) that feature ghost characters may have employed rigging as well to make these apparitions appear as though they were emerging from out of the great beyond. The issue with this was that the armour-clad depiction of ghosts of the period were often very difficult to move with the technology that was available to them. The weight of the armor made it take very long to lift, and required many stagehands on the other end of the rope to make it work. The spectral illusion that they had hoped to achieve was easily interrupted by the most minor of complications, rendering a scene that was intended to terrify or disconcert the audience into the butt of many jokes. In fact, it was for this reason that ghosts would soon begin to be costumed alternatively in a white sheet, as a form of “spirit drapery” (Jones and Stallybrass, 246). It is because of sub-par attempts at making stage ghosts fly that we have the iconic image of a ghost that is still emblematically in use today.

Faith, Trust, and Pulley Dust

Fast forward a few hundred years to Britain in 1904. The popular theatre landscape had been dominated almost entirely by cookie-cutter melodramas and well-made plays for decades, and was slowly beginning to embrace the new naturalistic style of Ibsen and Strindberg that had been taking the Scandinavian theatres by storm. This was the year that one landmark production surfaced, leaving its indelible mark on British theatre history and completely reviving the spirit of “gravity defying” theatricals: that play was J.M. Barrie’s Peter and Wendy (better known as Peter Pan), which premiered at the Duke of York’s Theatre in London on the 27th of December that year. The story of a boy refusing to grow up, a family longing for excitement, a pirate holding a bitter grudge, and a Christ-like fairy evoking sympathy from even the most cynical of spectators; it is a timeless tale – assuming one can look past the racist portrayal of indigenous characters, which somehow has not hampered its continued appeal – that has been revived countless times all over the world ever since. Among the most iconic aspects of the play for which it is chiefly remembered is its breathtaking staging of children in flight.

The revolutionary flying effects were created by a specializing firm called Kirby’s Flying Ballet. It was founded by George Kirby in 1889, but it was not until his collaboration with Barrie in 1904 that his service really began to take off as a rare gem of theatre arts. Prior to 1904, “his flying apparatus was limited to primitive aerial movements; moreover the harness was extremely bulky, and since it took several minutes to connect it to the flying wire, an actor was invariably attached to his ungainly umbilical cord throughout the scene in which he had to fly” (Birkin, 109). Barrie tasked Kirby with creating equipment that was more discrete, which prompted Kirby to create a “revolutionary harness that not only allowed for complex movements, but could also be connected and disengaged from the flying wire within a matter of seconds” (ibid.). The rest, as they say, is history. Because of the ambitious vision of Barrie and the technical ingenuity of Kirby, flying actors via a rigging system became all the more believable in the eyes of audiences – some suspension of disbelief required. As a result, Kirby became an overnight sensation, with his invention becoming a highly sought-after commodity among deep-pocketed producers looking to capitalize off of the now popular illusion of flight before it became stale.

This abundance of producers wanting to strike while the iron was hot led to more and more plays being written to employ this technology. Although this became an amazing badge of success for Kirby – whose little firm that had previously been little more than an obscure niche – the plays began to pop-up all over the globe faster than Kirby could. In 1950 he sent an employee by the name of Peter Foy to New York to coordinate the first Broadway production of the musical adaption of Peter Pan. For the next seven years, Foy would manage all of Kirby’s accounts in America, while secretly spending much of his time tinkering with his own designs for improved rigging equipment. In 1957, he left Kirby’s Flying Ballet to form Flying by Foy, a firm of his own that ultimately inherited Kirby’s entire American market to become the industry standard on that side of the Atlantic.

Peter Pan has since become the epitome of theatrical flying, made evident by its frequent citation as the foremost exemplar of such. In the book, Stage Scenery: Its Construction and Rigging, a practical handbook of protocols for technicians by A.S. Gillette and J. Michael Gillette, the section on procedures for flying actors is prefaced with the almost anecdotal assertion that, “Few plays have as much appeal for both youngsters and oldsters as Barrie’s Peter Pan. Almost everybody has a desire to fly, and certainly a part of the fun and appeal of this play comes from the vicarious pleasure people receive from watching others fly” (Gillette and Gillette, 367). Even this predominantly clinical guide to backstage work cannot help inserting an editorial as to why this play is so appealing. Significantly, the answer proposed is an incredibly valid explanation for why stage flying is such an engaging practice, in this play and nearly all of the other examples traced in this survey. The source of Peter’s flight power is linked directly to his rejection of aging; Barrie tells us this in Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens, his 1906 novel recounting Peter’s origin story, when he very matter-of-factly states (as if it is common knowledge) that all children “having been birds before they were human, [are] naturally a little wild during the first few weeks” (Barrie, 299), and Peter is therefore able to fly without the assistance of Tinkerbelle’s fairy dust because his refusal to age has allowed him to retained the perks of his avian infancy. If adult humans are, according to Barrie, the subsequent stage in the evolution of birds, then the act of Peter and the Darling children flying is an extension of the thematic defiance against the natural process of developmental maturity. That said, youngsters enjoy watching the airborne spectacles of the play because it speaks to the wide-eyed belief in magic that they still possess, and oldsters can appreciate it out of a nostalgic longing for that same belief that they have lost upon entering the adult world. Flying represents the impossible, and that is something that everybody needs to embrace from time to time, even if only for the two hour’s traffic of the stage before returning to the real world and all of its heavy-weighing limitations thereafter.

Everyone Deserves a Chance to Fly

Although rigging productions became all the more common in the post-Kirby theatre, making actors fly continues to take a lot of supplementary effort, as well as requiring many additional safety considerations that consequently make it cost a lot more to mount a show that necessitates such spectacles. That being the case, it is predominantly the theatres with money (i.e. big-budget commercial theatres) who can afford to get these plays off the ground. This sector of the industry is primarily occupied by the grandiose Broadway-style musicals. Since they are the ones who can afford to not only make actors fly, but make them fly believably, companies specializing in these types of costly plays designed for bourgeois consumption quickly acquired a monopoly in flying in the theatre.

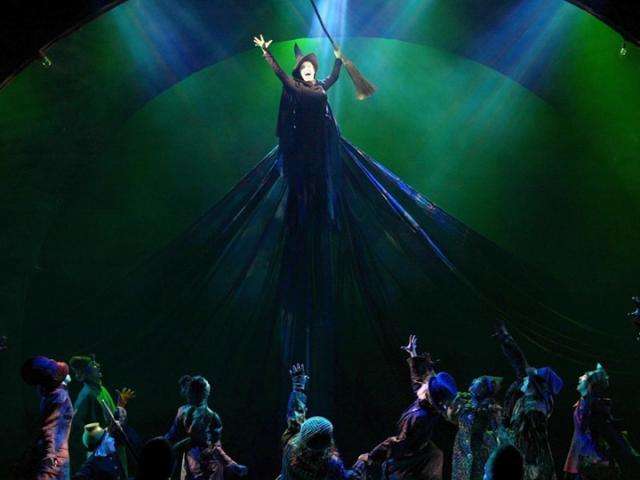

There are a number of big budget musicals known for their high-flying spectacles, from stage adaptations of A Christmas Carol and Mary Poppins, all the way to Billy Elliot and Spider-Man: Turn Off the Dark, just to name a few. One in particular that holds a special place in the history of contemporary staging practice – thereby making it a worthy subject for additional scrutiny – is Stephen Schwartz’s Wicked. Being a play that is so deeply hinged on the concept of “Defying Gravity” (which happens to be the title of what is unambiguously its most well-known song), it made a special point of employing a re-imagined approach to staging the act of flight.

In Carol de Giere’s book, Defying Gravity: The Creative Career of Stephen Schwartz from Godspell to Wicked, she recounts the story of how director Joe Mantello devised the system by which Elphaba (the soon-to-be Wicked Witch of the West) would “defy gravity” at the extraordinary musical climax of Act One. “To stage it, Mantello instinctively knew not to use the traditional Peter Pan type of flying back and forth. He believed people would start looking for wires and stop listening to the deeply emotional song” (de Giere, 367). This provides some context to the latter development of Kirby/Foy-style fly systems, which by 2003 – nearing a century after the first production of Peter Pan, which had amazed audiences with its ground-breaking approach to aerial staging – had become overdone. A new method therefore needed to be conceived.

What they came up with was a way for her to rise up vertically on a hydraulic platform while her black cape flows down and out of the light to cloak the mechanical evidence in a shroud of darkness. With the right lighting to defer focus away from the hidden apparatus, it looks exceptionally seamless. Of this, Mantello said, “Their [spectators’] imaginations can do so much more than anything we are capable of doing in the theatre. So my job, I felt , was to engage their imaginations so that they said, she’s flying – I didn’t tell them she was flying, but in their imaginations they saw her flying” (his emphasis; quoted in de Giere, 367).

The result was something truly mesmerizing, simultaneously taking advantage of the technology that was available to them while keeping everything deceptively simple. From an evolutionary perspective, this imagination-oriented approach may seem to be a less noteworthy innovation than that of Kirby a century prior, since its method has not been replicated on every subsequent production that required flying. However, perhaps it is better that way; this method of the flight illusion has yet to become tiresome and predictable. Though it can be difficult to speculate what the future has in store, it seems unlikely that, a hundred years from now, a director of a new play will be saying, “I instinctively knew not to use the traditional Wicked type of flying.”

Another form of theatricalism in a similar vein that must be addressed as well is circus performance, specifically trapeze and other aerial acts. The key difference between circus aerials and plays like Peter Pan and Wicked is that the spectacle of the flight is the focal point of the performance, rather than a means of visually complementing the action of a larger story being told. By supplementing narrative with “death-defying” feats of physical acrobatics, it blurs the lines between art and athleticism, illustrating how the act of flying through the air alone is enough to sustain an evening’s entertainment. Sally Jane Norman has described the appeal of these kinds of performances in saying, “Acrobats propose projections of living bodies that defy the rules of locomotion that govern the rest of us, heavy earthlings as we are” (Norman, 197). In theory, this reasoning applies to all of the abovementioned performances, but what makes acrobats particularly exceptional is their specialized athletic skill. Anybody can tie a rope around their waist and have others hoist them up, but these performers make themselves fly by their years of honing in on this near superhuman ability to the point of sheer biomechanical perfection.

There are No Strings on Me

Although there are innumerable other examples of ways in which fly systems have been used for theatrical spectacle throughout history (so many that it would be impossible to cover them all), it is also important to address ways in which performances have innovatively created similar illusions without the use of such mechanical technology. In many cases – not unlike the example of the rooftop placement of the God character in the medieval pageant plays – an illusion of flight can be created without the use of ropes and rigging. One noteworthy example comes from French-Canadian visionary auteur theatre director and certified wizard, Robert Lepage, whose theatre company (appropriately named “Ex Machina”) has been pushing the envelope of theatre’s supposed limitations since its inception in 1994.

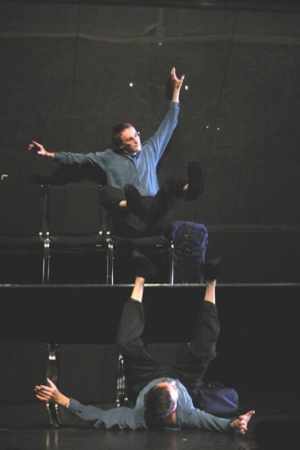

Lepage has provided scholars with no lack of subject matter to discuss in his oeuvres, but the one production of his that best applies to the topic at hand is The Far Side of the Moon, his 2000 solo piece about the space race, navel contemplation, and the reconciliation between two brothers (Philippe and André) in light of their mother’s death. So much of this play interlays motifs of outer space with Philippe’s desire to rise above his earthly struggles, which ultimately culminates at the very end with a jaw-dropping piece of theatricality that can be defined only a testament to Lepage’s artistic genius.

The stage direction in the published script says, “he rolls smoothly over the ground. His image is reflected in the mirrors placed above him. He performs a sequence of movements in slow motion, giving the impression that he moves in a state of weightlessness.” (Lepage, 77; translation from the French, courtesy of Google Translate). The result is an astounding image of flight, which unlike all of its predecessors, is achieved without ever leaving the ground. By rolling on the floor adjacent to a strategically placed and angled mirror that projects his image upwards (not unlike a periscope), he creates the unmatched illusion that he breaks free from the Earth’s gravitational pull and gently floats all the way up to the moon to see its elusive other face. Mark Leiren-Young, of the Vancouver Sun, described this by saying that, “There are moments the movement seems stylistically closer to modern dance that simple theatrical staging especially the dazzling final scene which brings to mind people’s disbelief a century ago when they realized what true magicians could do with mirrors.” From a horizontal position on the floor, he creates as sense of defying gravity that is more impactful than the actual lift that would be created by rigging. Perhaps this illustrates how illusion is so often more powerful than reality, a guiding tenet of theatrical praxis.

In 2003, Lepage made a film adaptation of this play, and attempted to translate the same effect from stage to screen. In a DVD bonus feature, titled The Creative Space of Robert Lepage, the film’s visual effect’s designer, Martin Lauzon, discussed how they went about transferring this illusion from one medium to another:

Robert’s initial approach was to recreate the choreography by rolling on a green carpet. That pushes the limits of green-screen technology too far. It’s unworkable. The green-screen should be distanced from the actor, in order to isolate him and place him in another setting. So, ultimately, there should only be one shade of green. We should simply be able to click on him and remove him. Above all we had to preserve Robert’s choreography which he’s been doing in the theatre for years. We suggested using a harness, or something else I’d thought up, but it made the scene awkward. It was more important to preserve his artistic vision, rather than the technology […] We worked long and hard to salvage it and isolate him. But what’s always most important is to stay true to the actor’s vision. (Subtitled translation from the French provided by CNST, Montreal.)

The upsetting fact of the matter is, this scene in the film is not nearly as effective as its counterpart in the play. It was probably still wise of them to not resort to using a harness, as that would likely have removed the very soul of the piece; and yet, in spite of the best efforts of everyone involved, it still looks somewhat awkward. The problem appears to be chiefly due to the overall theatrical (as opposed to cinematic) nature of the illusion. Today’s movie-goers are so preconditioned from seeing big-budget blockbusters that are capable of counterfeiting reality with remarkable accuracy. Regardless of one’s personal preference between theatre and film, there can be no denial of the latter’s ability to generate true verisimilitude in its special effects in ways that the former simply cannot.

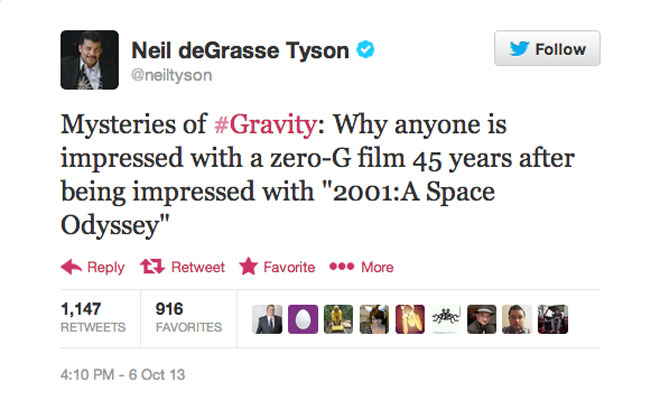

Ever since the landmark achievement of Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), creating realistic anti-gravity effects has become sort of a rite of passage for science fiction filmmakers trying prove that they are worth their salt. Between such films as Andrei Tarkovsky’s Solaris (1972), George Lucas’ Star Wars (1977), Steven Spielberg’s E.T. (1982), Ron Howard’s Apollo 13 (1995), Juan Diego Solanas’ Upside Down (2012), and most recently Alfonso Cuarón’s Gravity (2013), among countless others, seeing the defiance of gravity on the silver screen has become a relatively common occurrence – which makes it somewhat less impressive than intended when a film, like Gravity, decides to centre its entire premise around the creation of such effects (as was was humourously noted on Twitter by Neil deGrasse Tyson). If Lepage wanted to compete with these films on their own turf, he would have had to re-adjust elements of his performance style to something more cinematic in nature.

Postgravity Theatre

In each of the examples discussed so far, the illusion of flight has been created with the use of ropes, harnesses, platforms, or mirrors. Though these tools have been very successful for thousands of years, some of the most radical alternatives to emerge in recent history have taken things one giant leap further. In these performances, gravity itself (be it a lack thereof) is the primary agent that creates a genuine sensation of flight, taking the concept of flying in performance to a whole new level. The defining characteristic of this difference is weight versus weightlessness. A pulley system is designed to counterbalance the weight of an object in order to allow it to lift, in spite of its own mass; in the following performances, weight is not at all a factor. The tools being used here are “Reduced Gravity Aircrafts” (RGAs) by means of parabolic flight. The concept was first proposed by Fritz and Heinz Haber in 1950 as a method of preparing astronauts for the gravitational conditions of outer space (Haber and Haber, 395), but has since been applied in a variety of other creative ways. One these creative uses is what contemporary Slovene director, Dragan Živadinov, refers to as “postgravity” theatre. By staging theatrical works inside flying RGAs, gravity becomes literally defied in a way that could scarcely have been imagined by Aeschylus, Barrie, and Mantello. Instead of working within the confines of gravity to create lift, these works take place in environments where gravity (momentarily) is not at all present, and therefore requires no further effort to be combated.

Živadinov is perhaps best known for his integral affiliation with the Slovene multidisciplinary arts collective, Neue Slowenische Kunst (NSK) as their chief theatre exponent, forming numerous production companies under their banner since the early 1980s. His first project to truly characterize this postgravity notion was his 1999 piece, Biomechanics Noordung. A small group of actors and spectators were brought up into the air in an Ilyushin-76 MAK aircraft (RGA) used by the Yuri Gagarin Cosmonaut Training Centre in Star City, Russia. The experience has been describes as follows: “spectators, critics, performers, scenery, and objects alike were set into zero-gravity conditions, freely floating in the air for between twenty-five and thirty seconds, directly in the middle of a fully staged theatrical play” (Salter, 73).

In addition to the purely experiential facet of this performance – which is miraculous in itself – there is a deeper sociopolitical layer hiding within its subtext, as is the case with all NSK works. In Alexei Monroe’s Interrogation Machine, he says that, “Noordung actions embody the concerns of all NSK groups to escape the ‘gravitational’ pull of the historical, political, artistic, and economic regimes that structure their environment” (Monroe, 265). Given the tumultuous history of former Yugoslavia – especially in the years leading up to this performance – the desire to transcend all worldly boundaries may bear with it a more deep-seated resonance than the mere physical thrill of making your internal organs dance. This form of transcendentalism can be furthered to surpass its own political constraints through a heightened sense of release from politics and its burdens, symbolized by the release from gravity itself. In 1998 (one year prior to this piece), Johannes Birringer writes, “The antigravity conception of his future theatre implies a kind of altered state, a form of mental space travel that shifts theatrical perception of the real to a different, planetary level” (Birringer, 58). It allows its participants to enter a world of their own, freed from all terrestrial turbulence down below.

Another production of Živadinov’s that follows this thread is his Noordung Prayer Machine (often alternatively titled as One to One). The interesting thing about this piece is its unconventional performance schedule, being presented only once every ten years. The first installment was in 1995, followed by plans to compound it in 2005, 2015, 2025, 2035, and a grand finale scheduled for 2045. Each successive performance takes into account the technological developments that have transpired since the previous one, and infusing them into the next version. In 1995, one of the performers was raised into the air on a “floating” object that was hoisted upwards using very traditional rigging technology like those discussed above. By the time that the final performance occurs, it is expected to be able to float up without the threads that currently hold it in place.

The long span between the first and last performance promises many other possible changes during the interim, one of them being the high likelihood that some (if not all) of its sixteen cast members will die before 2045. This possibility is not only accounted for, but has become a key component of the piece’s essence. There are many different accounts of how actor’s deaths will be managed, but the most reliable – and most bizarre – comes directly from Živadinov:

If an actor dies in this time interval, his text will be substituted by rhythm, while if an actress dies, her words will be replaced by melody. According to the mise-en-scène, where a live actor performed, we’ll use a substitute of the actor. First a model, but after the actor’s death, it will become a module. In 2045, I will take, by rocket, all the sixteen modules into the equatorial orbit, 400,000 meters above the Earth. I will place them around sixteen different spots around the planet Earth, next to the information satellites. There will be a teleportable apparatus inside the material, sending the story about the deceased actor to the satellite, and the satellite will regularly transmit the story about the actor, who was on planet Earth and was changing, or transforming, back to the planet. (Živadinov, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XUr1zGq5OMM)

It is not easy to tell to what degree his eccentricities are truly serious, versus the possibility that it may be part of this larger-than-life persona that he has created for himself in executing these (for lack of a better word) wacky performance ideas. Sally Jane Norman’s account of this omits all mentions of rockets and teleporters, and rather simplistically says that it will end with “Živadinov’s own death at the final performance in 2045” (Norman, 198). Although his death may be the most likely outcome of him attempting such a voyage by rocket beyond the stratosphere, Živadinov himself alludes to nothing of the sort. His trip to space, as the sole survivor of his ambitiously lengthy project is meant to be, not a death, but instead a final “farewell ritual” to the world, and all of the gravity that it has been using to keep him down.

There have been other artists to utilize RGA technology in their work; one of the more notable being French choreographer, Kitsou Dubois. Often finding herself in the the same planes as Živadinov, and working with their mutual collaborator, Marko Peljhan, it is contested among scholars which of them was the first to experiment with the theatricality of parabolic flight (La Frenais, 56). Through her work with Arts Catalyst (a UK-based arts and science hybrid organization), Dubois has published numerous articles on her findings with regards to dance in weightless environments, which have greatly influenced subsequent astronaut training programs to diminish the amount of motion sickness experienced in orbit. The one major downside to her postgravity performances is that, though many of them have been filmed, she has not brought audiences up into the aircraft with her to witness the experiences live. A large part of what made Biomechanics Noordung so special was that it allowed performers and spectators alike to float simultaneously in its reduced gravity setting. Though watching Dubois’ videos can be just as remarkable as watching film adaptations of Peter Pan and The Far Side of the Moon, this passive external position is nowhere near the same as the phenomenological experience that Živadinov provides to his audiences.

Conclusion

This has by no means been a complete historical survey, but rather a key sampling of the important theatrical events in the history of artistically-driven flight simulation. It is clear that mankind has always had a desire to fly, and theatre has historically offered a release valve in which we can attempt to act upon this longing. Gravity is a physical force that has held our species down; it is this fundamental law of nature that has fueled such a long series of innovative developments in order to conquer this limitation: innovations in the fields of science and transportation (from airplanes to rocket ships) as well as theatre and performance (from pulleys to RGAs).

In May of 2012, the Mars One organization announced their intentions to establish the first human colony on Mars by 2026. If such an outlandish dream should ever come into fruition, it is not illogical to assume that theatre will eventually insert itself into the fabric of these newly established cultures – just as it has done with practically every other human civilization throughout history. With the help of people as passionate about space exploration as Živadinov and Dubois, who have already begun preparing theatre to adapt to the foreign conditions, the task of aestheticizing outer space may not be as difficult a feat as one might expect. It would not be at all surprising if Živadinov were selected to be part of their mission, aboard which he will surely provide the entertainment. Just as the works staged inside RGAs were the next evolution of theatrical flying after the long tradition of ropes and pulleys, the theatre that will be performed beyond the Earth’s atmosphere will no doubt be the next evolutionary stage to come. It is only a matter of time until we boldly go where no theatre artist has gone before.

Works Cited

Aristotle. The Poetics. Trans. Preston H. Epps. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1970.

Barrie, J.M. “Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens.” Ed. Alton, Anne Hiebert. Peter Pan. Peterborough: Broadview Editions, 2011. 287-341.

Birkin, Andrew. J.M. Barrie and the Lost Boys: The Real Story Behind Peter Pan. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003.

Birringer, Johannes. Media & Performance: Along the Border. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998.

Craig, Edward Gordon. On the Art of the Theatre. New York: Routledge, 2009.

Davidson, Clifford. Technology, Guilds, and Early English Drama. Kalamazoo: Medieval Institute Publications, 1996.

De Giere, Carol. Defying Gravity: The Creative Career of Stephen Schwartz from Godspell to Wicked. New York: Applause Theatre & Cinema Books, 2008.

Dragan Živadinov- NOORDUNG, Cosmokinetic Theatre. Dir. Tone Stojko. Perf. Dragan Živadinov. 1999. Online video.

Gillette, A.S. and J. Michael Gillette. Stage Scenery: Its Construction and Rigging. New York: Harper & Row, 1981. Print.

Haber, Fritz, and Heinz Haber. “Possible Methods of Producing the Gravity-Free State for Medical Research.” Journal of Aviation Medicine. 21.5, 1950. 395-400.

Jones, Ann Rosalind and Peter Stallybrass. Renessaince Clothing and the Materials of Memory. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

La Frenais, Rob. “An Introduction to Vertigo.” Hill, Leslie and Helen Paris. Performance and Place. Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006. 52-59.

Leiren-Young, Mark. “Review: Far Side of the Moon takes flight as star shines.” The Vancouver Sun. 2 November 2012.

Lepage, Robert. La Face Cachée de la Lune. Montreal: L’instant Même, 2007.

Monroe, Alexei. Interrogation Machine: Laibach and NSK. Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2005.

Norman, Sally Jane. “Anatomies of Live Art.” Ed. Bleeker, Maaike. Anatomy Live: Performance and the Operating Theatre. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2008. 187-204.

Normington, Katie. Medieval English Drama. Cambridge: Polity Press, 2009.

Renault, Mary. The Mask of Apollo. New York: Pantheon Books, 1966.

Salter, Chris. Entangled: Technology and the Transformation of Performance. Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2010.

The Creative Space of Robert Lepage. Perf. Martin Lauzon. 2003. DVD Bouns Feature.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Whenever I see flying on the stage, it gives me a heightened reality or emotion.

All the effort into stage flight is in the name of creating a spectacular theatrical experience for the audience.

For a time in ancient Greece, flight on stage became so common that the comic poet Antiphanes remarked that when playwrights no longer know what to do, “just like a finger, they lift the machine and the spectators are satisfied.”

Stage flying is nearly as old as theater itself.

Excellent article. Continue in the same spirit.

I work in this industry. It is extremely important that the operators and staff fully understand how the fly system works and what safety precautions must be taken when loading and operating the system.

I’m wondering how things will look like in a few decades. Will it be zero gravity, if you get my point.

Thank you for sharing, great post.

Seventeenth century sailors often found employment rigging and flying in theatres. As on a ship, they used to communicate with each other through whistles, different whistles meaning commands like ‘bring the set in’ and ‘all clear’. If an unlucky actor happened to be walking across the stage whistling, they could find a set piece coming down from above.

As a theatre performer, in order to achieve effective performer flying from the simplest effects to the amazing feats, it’s essential that the performers trust the equipment and the crew they are working with.

This is very true. Speaking from experience, a strong team make a far superior show.

Zivadinov is a pioneer and most important to the development of performance.

One of the earliest records of flight on stage was the 425 B.C. production of Euripides’ “Medea”.

There is an ever-increasing desire from audiences to be thrilled by the show. Little do they know… these techniques have existed for a very long time. Just upgraded to our generation.

A plain, vertical movement can appear rather dull. Glad things have evolved over the years.

Lovely article. I will share it in my Theatre Appreciation classes.

A theatre’s flying system is a vital way of effecting quick scene changes.

That is a great article! Being a theater person, this is incredible!

Thanks for noting Ancient Greek. Ought to be clear from this – much of what we are debating, arguing, talking about, discussing, and experiencing, was already part of the Greek scene in ancient times.

The very idea of theatre – and the word itself – both from Greek.

Shakespeare used a variety of special effects at the Globe, including flying actors using a pulley system, flymen and ropes, a technique which is still used today.

Thanks for your writeup on aerial work, really interesting!

Totally sharing this on my social media channels, thank you for a great article on stage performance.

I believe we can safely say that as long as there are people and performance, there will be flying, and it will undoubtedly incorporate ever more ingenious and sophisticated technology.

I love the observation that flying in the theatre is a way to defy our earthly limitations, and a reason for choosing a career in the theatre. Well-cited and informative!

Why do people even attend theatre when you can go to the movies?

Love it

Re: the Deus ex machina: Athena appearing to save Odysseus in the final books of the Odyssey (I believe the final one, Book XXIV) from the Ithakans is an Example of this from about 800 BC (in the oral tradition; written about 400 BC).