Urban Fantasy’s Monstrous City

And a city the size of this one, with all the hiding places it contained, would make such a perfect hunting ground for a demon—especially one that could look like a cloud of smog. (Children of the Night, Mercedes Lackey, 1990)

That was what they wanted, what they all wanted: to feed until they killed. The power of life and death. (The Sweet Scent of Blood, Suzanne McLeod, 2009)

They stood among the ancient grave markers of the small family cemetery, waiting. Nothing waits as patiently as the dead. (Guilty Pleasures, Laurell K. Hamilton, 2007)

The opening epigraphs were selected as examples of elucidating fear, anxiety and dread in urban fantasy (UF) narratives. For example, the use of the terminal space of the graveyard is a staple of any horror story, as demonstrated by Laurell K. Hamilton. A place that reminds us of our mortality, tainted by superstition and fear, the graveyard is a landscape already connotative of dread. In addition, UF authors go beyond such stock locales and delve into the city itself to reveal the myriad liminal spaces and confined places of the city edifice. As Mercedes Lackey indicated, a city is full of hunting grounds suitable for the supernatural. In turn, Suzanne McLeod reminds the reader that the creatures that stalk the cities are the salver an author uses to evoke the thematic concerns of fear, anxiety and dread—for what is more terrifying than the threat of death?

UF is a complex genre and for those who are not experienced with what this means, or would like to know more about the genre as a whole, feel free to examine this definition first, ‘Defining Urban Fantasy.’

UF has deep roots—it draws on ancient myths and folklore, the terror and gore derived from horror and dark fantasy, and the more subtle atmosphere of fear and dread of gothic literature. As a subgenre, like any other fiction, UF touches on a wide variety of thematic concerns. However, at its core are the prevailing concerns of fear, anxiety and dread. These themes are a consistent element due primarily to UF’s choice of situating its tales in an urban landscape. The aspects of the non-rational, supernatural, violence and gore are present in UF as aids in developing the concerns of fear, anxiety and dread. However, UF is fundamentally tied to the city; thus, it is the presence of those aspects within the city that evoke these thematic concerns. The urbanscape that UFs develop are necessarily based in the real world because they conform to this need as a characteristic of the subgenre. UF authors deliberately connect the intersection of the non-rational and real-world setting of the city to unsettle the reader. For what is more terrifying for an audience to realise what they witness may too come for them?

The familiarity of the setting in UF works in a similar manner to popular horror fiction. It uses the threat of within-the-known to excite a negative response in the reader. As a theme, fear occurs often in fiction because it is a ‘reliable source of suspense, conflict, and reader identification.’ 1 UF introduces fear, anxiety and dread into the narrative because these are recognisable concepts for any city dweller. The flipside to the modern, freeing city is the dichotomous den of darkness and danger. In turn, UF deliberately develops particular landscapes that are able to feature these thematic concerns.

Our Fear of the City Itself

Any form of dark fiction draws on these similar thematic concerns as they work to unveil the deeper psychological concerns at place in the literature. They help to reveal our worldly concerns and, as such, indicate why readers are drawn to them. This point was made by Dani Cavallaro:

We cannot resist the attraction of an unnameable something that insistently eludes us. Narratives of darkness nourish our attraction to the unknown by presenting us with characters and situations that point to something beyond the human, and hence beyond interpretation—a nexus of primeval feelings and apprehensions which rationality can never conclusively eradicate. 2

Cavallaro argued that readers are drawn continually to tales that evoke their darker imaginings. A reader may realise also that the monsters of fiction are frightening because they are already present and representationally believable in our minds. Yet stock monsters, extreme violence and obvious metaphors are not enough to evoke readers’ deeper, more primal fears. The traditional role of dark fiction is to help readers learn to dispel their fears, much akin to the role fairy tales held in ancient societies. Thus, it is necessary for the narrative to develop believable (in the context of the story) elements that unsettle, but do not evoke disbelief. UF authors must then draw on atmospheric qualities to guide the reader into moments of fear, dread and anxiety within the believable boundaries of their cities. The atmospheric element is best explained by H. P. Lovecraft:

The true weird tale has something more than secret murder, bloody bones, or a sheeted form clanking chains according to rule. A certain atmosphere of breathless and unexplained dread of outer, unknown forces must be present; and there must be a hint, expressed with a seriousness and portentousness becoming it subject, of that most terrible conception of the human brain—a malign and particular suspension or defeat of those laws of Nature which are our only safeguard against the assaults of chaos and the daemons of unplumbed space. 3

UF relies on both the unsettling insertion of the supernatural and the already fixed presence of fear in the city. If the city evoked less ambiguity in the minds of society, then the incursion of the non-rational would fail to upset and disturb. Thus, to enrich their narratives, UFs employ the already present struggle with tensions, threats and fears common to a modern city.

UF follows a plot structure more similar to gothic or detective fiction, where the agents become known before the final confrontation, and the gore, though present, is not imperative to the development of the atmosphere. Instead, a primary characteristic is fear created by an awareness of impending threats and danger. The protagonists are hunters who actively seek out the danger, which does not alleviate the reality of that threat, but instead heightens the feelings. The fear in UF can range from facing the supernatural to incremental fears of not knowing, which Patricia Briggs identified in Moon Called as ‘[n]ot the kind of fear you feel when unexpectedly confronted by a monster in the dark, but the slower, stronger fear of something terrible that was going to happen.’ 4 Fear of the unknown occurs throughout the UF narrative; however, it is alleviated by revealing the antagonist early in the plot. Fear is used to provoke the reader into considering the outcomes of the threads facing the protagonist.

Also present in UF is a more primal threat—of dying. After all, to be mortal is to be concerned by death. UF evokes a range of primal emotions along a spectrum of violence, murder, death and terminal landscapes. Dread is not simply fear, but is touched by an awe or reverence for that which evokes fear. The deliberate use of terminal landscapes, at times death-scapes, provokes this sense of dread. In particular, vampires are creatures designed to conjure a mix of reverence and fear. They represent a form of immortality, as well as being disturbingly unnatural. UF authors exploit the landscapes of the city environment—both natural and unnatural—to produce a sense of dread, which works to awaken other emotional experiences. Cavallaro 5 suggested that, in experiencing dread, a reader turns to curiosity and anger. In the anticipation of dread lies ‘a consuming desire to know who or what is unsettling us’, 6 thus evoking curiosity, while anger comes from ‘a sense of irritation produced by the impossibility of final knowledge.’ 7 Dread becomes a gateway to a range of other sensory emotions by the reader. The author encourages the reader to engage more fully with the actions or environment of the narrative by developing a sense of dread.

The concern with unnaturalness and disorder is at the heart of humankind’s monumental triumph over nature—the city. The urban environment is meant to protect, yet, within its walls, people are aware of the threat of that order descending into chaos. This understanding underpins the sense of anxiety that runs throughout UFs. The liminal spaces, city edifice and tensions between past and present all emphasise the anxiety that is already a part of city life. The violation of cultural boundaries within the city—aided by images of disorder, alienation and monstrosity—is unsettling. 8 Yet it is recognisable in a real-world city as the source of anxiety. UF adds a non-rational element to the narrative, but is drawing on anxieties already present in Western cities. At their core, UFs are primarily urban dramas that build on already-present thematic concerns with the incursion of the supernatural. The threads of fear, anxiety and dread tie UF cityscapes together more completely than any other thematic concern.

Liminal Spaces and China Mieville’s King Rat

Within the boundaries of the city are spaces and vantages that offer a uniquely disturbing landscape that is able to inspire fear, anxiety and dread. As a form of fantasy fiction, UF is an imaginary and illusionary subgenre that offers itself easily to the creation of liminality. As such, authors have seized on this and developed liminal spaces within the city. Such transitionary locales offer a thinning of the boundaries—a way for the supernatural to intersect with the ordinary. They are temporary and at times able to occur unexpectedly. Thus, they appeal to our inner anxiety about the changeable nature of the world. Their continued presence throughout the tale evokes fear and dread, opening up the space to examine the inherent fears of city dwellers.

Liminal refers to being on the boundary or threshold of different states, or existing in an intermediary or transitional position. The liminal state is almost a position of limbo, and those undergoing this transitionary period exist without clear definition. These liminal spaces are necessarily only available to characters that exhibit liminal characteristics. The ability to cross into these liminal spaces is a particular characteristic of the UF protagonist. Their ability to traverse these landscapes imparts power. Yet the protagonist does not exist exclusively in such spaces; instead, the liminal mythic characters the protagonist hunts or associates with primarily occupy such zones of the city. In addressing the question of liminality, Charles La Shure 9 identified that, for liminal mythical characters, liminality must be their original state. Their existence in these liminal spaces ‘allows them access to the social structure at any number of points, much like a sewer dweller would have access to a city at any number of points.’ 10 These antagonistic mythical characters are able to emerge from the liminal spaces ‘betwixt and between’ a city, and influence the ordinary world. Thus, they are able to ‘flit across the borders at any time, penetrating the social structure at will, but [they] cannot stay there’ 11 In contrast, the protagonists must act as a bridge between the real-world setting of the city and the liminal zones of the fantastic. The protagonists’ unique characteristics (often supernatural in form, but not always—as in the case of musicians, poets, artists or so forth) allow them to pass into and through the liminal spaces to which mythical characters become confined. The clearest example of this is China Mieville’s King Rat novel. 12 There, the human protagonist, Saul, traverses both the city and underground to gain power, while his mentor, King Rat, is weakened when leaving the liminal space of his sewer home.

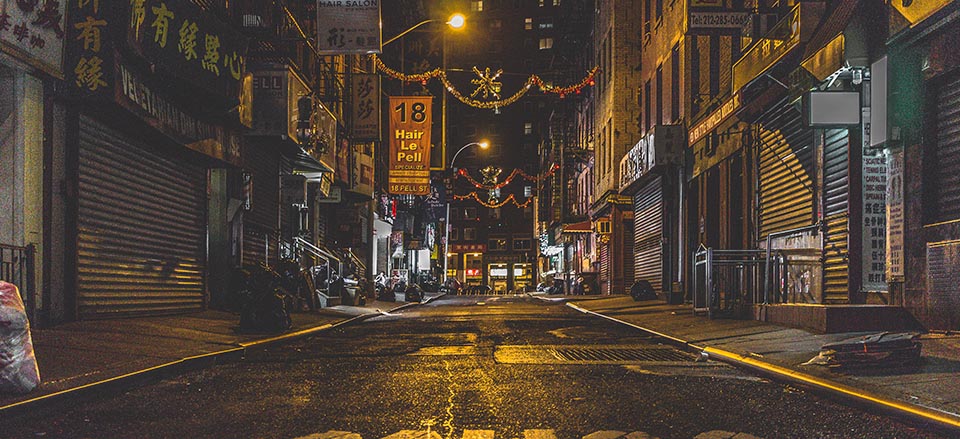

UF authors tend to develop liminal spaces such as those that exist on the edges of human society. In a city, this can refer to the literal outskirts (often slums, ghettos or industrial areas), but also to spaces that are unique to a city, yet often overlooked or ignored by daily city dwellers. Common choices are the underground sewer systems, water courses, ancient cave systems, crypts and basements. These places exist below ground, are often ignored in ordinary life and still retain a taint of the unknown. Liminal spaces are also the abandoned or forgotten places around a city, such as alleys no longer commonly used, rooftops without access points, rubbish or construction dump sites, abandoned transport centres, and unfinished or decayed buildings. They are locales forgotten or abandoned for various reasons, and while they may still be used by people, these are people already on the outskirts of humanity—the homeless, lost, infirm, insane, runaways and so forth.

In turn, ordinary spaces can also become liminal when their usual purpose in usurped by the non-rational. This is when the supernatural is able to subvert a traditional space for its own use. It is a distinct part of UF that the known may be turned unknown by the presence of the supernatural. The supernatural are able to render the ordinary fantastic, and subsequently create the liminal in the truest sense. These are transitionary, in-between spaces that are able to operate in a temporary state for the actions of the supernatural to occur. A further element is often incorporated to add to the mythical transformation of the city space into a betwixt space, such as night-time, shadows or locales of transfer (stairs, alleys, windows, doors or transportation) that link a start and end point. Any space that can be used to represent a midpoint can be adopted as a liminal space.

Liminal spaces in UF serve a number of vital purposes. First, they provide a distinct locale within which the supernatural and antagonists can operate without causing dissonance from the believability of the real-world setting. Even though a number of UF authors have inserted supernatural creatures into the ordinary parts of their cities, it is notable that, in these spaces, they behave in expected human roles. For example, the vampires in Laurell K. Hamilton’s series are often strippers or entertainers at night. Their job suits their lifestyle and is not beyond believable. In a similar manner, when UFs include shapeshifters and were-animals, whether the world knows of their existence or not, they remain in human form in public and hold human jobs, rather than roaming the streets in their animal form. Thus, the supernatural is incorporated into city life in a believable manner. The liminal space is then able to offer a believable locale where the otherworldly can expose their otherness. Urban liminal spaces are already imbued with particular connotations that the UF author uses for atmospheric purposes. Operating in these spaces helps emphasise the otherness of the supernatural. By locating their stories in these below, forgotten, abandoned places or by corrupting the safety of the known, UF authors are able to develop strong senses of fear, anxiety and tension in the reader.

The most commonly developed liminal setting is the below space. A ‘below’ urban setting is associated with myth and instinct, drawing on a rich background of classical mythologies. Below has always been associated mythically with underworlds. Two well-known examples are the Orpheus myth of travelling to Hades’ Underworld and Dante’s journey into Hell. Even contemporary parodies and popular-culture representations of Hell are commonly located in an intangible ‘below’. In the urban context, these subterranean spaces are also populated with imagined myths and horrors. For example, the sewers—a place whose purpose is to discard human waste—are a source of disgust and ignorance, and already hold a popular-culture association with urban legends and horror stories, such as the alligators that live in New York’s sewers, or the ‘below’ people of dystopic stories that emerge to kidnap and kill the ‘above’ people. UF novels tap into a mythos (both classical and modern) that is already strongly in place. Even without the mythic, human instinct shies away from places that enclose us or are associated with waste and discard. The UF novel that most successfully captures the liminal space of the sewers is Mieville’s King Rat. The sewer system under London has already been developed by authors of urban realism or horror. It is a system that allows criminal elements to travel unseen, undetected by the ordinary citizens. It is a place to hold secret meetings and hide a body. It is a space occupied by only the most rejected of society, and by rats. Mieville’s character King Rat is the human embodiment of a ruling rat:

I’m the big-time crime boss. I’m the one that stinks. I’m the scavenger chief, I live where you don’t want me. I’m the intruder. I killed the usurper, I take you to safekeeping. I killed half your continent one time. I know when your ships are sinking. I can break your traps across my knee and eat the cheese in your face and make you blind with my piss. I’m the one with the hardest teeth in the world, I’m the whiskered boy. I’m the Duce of the sewers, I run the underground. I’m the king. 13

King Rat represents the rats and their role as vermin, disease carriers and insidious citizens of the below. He, more than most UF characters, embodies the mythical liminal character and is subsequently inseparable from his environment.

The sewer system Mieville (2011) created is more than literal—it becomes a liminal space when King Rat reveals it to the protagonist, Saul:

Shapes moved in front of him. He thought they were real until the corridors themselves began to emerge from the darkness and he realised that those other fleeting, indistinct forms were born in his mind. They were dispelled as Saul began to see. 14

Saul learns to perceive the sewers as a space of fluidity. He sees more than the drains and walls, but also ‘the energy it contained spilling out’ 15—the ‘aura’ of the sewer space. Saul is inducted into the liminal space by a mythical trickster—the king of rats—who leads Saul into an unknown world that is separate, but clearly abutting, the real world, where ‘[o]ccasional growls of traffic filtered through the earth and tar above, to yawn through the cavernous sewers,’ 16 reminding the reader that this space is present below the streets of London. Mieville created a labyrinthine space that appears to have no start or end—it is a mid-space that only a rat could traverse at ease. As Saul observes, the ‘rule of the sewers were different, the distinctions and boundaries between areas blurred;’ 17 in opposition to the certainty of above-ground landmarks, the sewers take on a ‘sameness’—an endless quality. Akin to Dickens’s own representation of London, Mieville did not attempt to beautify the space; rather he was brutal in portraying the ugliness. It is ‘a study in perspective, the shit—and algae—encrusted walls … and everywhere the smell, rot and faeces, and the pungent smell of piss, rat piss.’ 18 Mieville’s sewers are functionally a concept for disgusting and unsettling the reader. Only Saul’s adaptation and rat-training allow him to exist in this space, and it is a transitionary space even for him.

As a UF novel, Mieville’s narrative does not remain isolated in the sewers. Mieville did not attempt to create a secondary world below the city streets. Instead, Saul must traverse the sewers, while learning to move between the sewers, the ordinary world and other liminal spaces of the novel. In many ways, Mieville’s novel is the most liminal of the UF subgenre because the protagonist and his mentor occupy almost exclusively liminal spaces, while the central antagonist moves in the ordinary world. When Saul is above ground, he remains in back alleys, feeds from dumpsters and travels across the ‘[a]lternative architecture and topography’ 19 of London’s rooftops. The places where violence and fighting occur are liminal—a hidden room in the sewer system built for King Rat, a vehicle demolition site that is abandoned and decaying, a ghostly subway station that is no longer in use and a derelict warehouse used by ravers. All such places are ignored in the ordinary world, but become battlegrounds and haunts for the otherworldly. Such liminal spaces are never fully forgotten or abandoned, but live ‘a half-life, never being finally laid to rest, haunted by the unlikely promise that [they] would one day open for business again.’ 20 All these spaces are decayed, broken, dangerous and isolated. They add to the atmosphere of fear and uncertainty because, unlike traditional fantasy battlefields, these UF liminal spaces offer the option that good will not prevail.

Saul comes to view the city as an entity of weakness—a place that is vulnerable when its secrets are learnt, and only a character who sees beneath the city’s façade can understand its truth:

This point of view was dangerous for the observer, as well as for the city. It was only when it was seen from these angles that he could believe London had been built brick by brick, not born out of its own mind. But the city did not like to be found out. Even as he saw it clearly for the product it was, Saul felt it square up against him. The city and he faced each other. He saw London from an angle against which it had no front, at a time when its guard was down. 21

Saul’s perspective allows the transformation of the entire city into a liminal space because, at its heart, a city is a place of transition. This view captures the anxiety associated with weakness and change that a reader can understand, which transforms the entire landscape of the novel into a place of ceaseless tensions. The illusion of Mieville’s liminal city is furthered by the development and focus on the individual liminal places where the action of the novel occurs. This causes the individual liminal spaces of the novel to become inseparable from the overall transitional nature of the city. Even as time moves forward and alters the uses and façades of a real city, the UF city locates in these changes the liminal, forgotten places left behind.

Terminal Landscapes

Further, owing to the focus on concerns of death, dying and the undead, UFs are populated with terminal landscapes—both in the physical locales associated with these concerns and the inclusion of undead characters who challenge the linear concept of existence. Places belonging to the dead are already touched by emotional awe and fear, since they are an unwelcome reminder of mortality. Thus, the creatures of the undead are a challenge to the sanctity of life, as they must take others’ lives to continue their own. It is easy to see how the undead evoke the same fear and dread as the landscapes they inhabit. The senses of fear, anxiety and dread are further developed by the presence of the city edifice. Arising from a history of gothic edifices, the city edifice contains the boundaries of the cityscape. It fulfils the characteristics of claustrophobic confinement, subterranean pursuit and supernatural encroachment. The city acts to enclose, confuse and subvert the ordinary and orderly spaces of the city.

In UF, the themes are often explored in what can be perceived as a terminal landscape—by which I mean a landscape involving, associated with, symbolic of or populated by death, dying or the undead. Such spaces can include, but are not limited to, morgues; cemeteries; hospitals; the underground; ancient ruins; burial grounds; crypts; or any space populated by dead bodies, bones or decaying bodies, vampires, ghouls, zombies or other forms of the undead. The inclusion of terminal landscapes is part of the underlying mythologies present in UF. Our association between urban and death has been present since the development of the earliest cities. Richard Lehan suggested that, as the first cities ‘were founded as a place where wandering tribes could return to worship the dead … the idea of the city has never been separated from the reality of death.’ 22 We attempt to deny our mortality, and equally yearn for and are appalled by immortality. From there rises the myths of the immortal vampire—a creature that may live forever, but is always a monster. Cities house the lives of people, yet also contain the dying and dead. UFs often centre on the transitionary stage of life into death and, through magic and myth, this can include the undead. Existence then becomes truly liminal because, with the option of being undead, the final resolution has been moved out of reach.

More so than other undead, the vampire represents a prototypical liminal character. It is a living corpse that symbolically violates the moral border of existence. For a vampire to feed, it must take the life force and blood of a living human—a fundamental violation of our belief in the sanctity of life. Laurell K. Hamilton in her long running Anita Blake: Vampire Hunter series delineated the difference between humans and vampires by identifying the ‘otherness’ of the vampire—the contrast to our warm mammalian selves:

There was a neck-ruffling smell to the room, stale. It caught at the back of my throat and was almost a taste, faintly metallic. It was like the smell of snakes kept in cages. You knew there was nothing warm and furry in this room just by the smell. 23

Hamilton’s protagonist, Anita, is a necromancer by birth and an animator, homicide consultant and vampire hunter by trade. Thus, her most common locales are terminal spaces populated by death. She is situated in bloody back alleys, ghoul-infested cemeteries, hospitals and morgues filled with ‘killer zombies’, murder scenes and burial grounds. Predominantly set at night, these spaces already belong to death. The further descriptions of violence and gore heighten the natural dread to become fear—a fear that is increased by the understanding that these terminal landscapes remain confined to the city. Although vampires serve as love interests, Hamilton’s vampires are depicted as monsters and unnatural. They sleep in coffins and live in underground spaces. The presence of the vampires becomes synonymous with blood and danger, regardless of the intimacy of a scene. Hamilton further related her vampires to sexual deviancies that stand against mainstream American culture. Linked to death, sex and violence, they are portrayed as unnatural and immoral. The vampire is a monster associated with a wide range of transgressions both socially and mythologically. This alternative nature was once associated with isolated ‘dark lands’, yet has now come to be connected with the urban. As humankind expands its borders, it is believable that vampires have slipped within the city boundaries to hunt.

Associated with elements of countercultural norms, the vampire has a tangible effect on the landscapes it inhabits. When feeding, killing, taking blood or hunting, the vampire becomes a siren of imminent death. Its hunting zones then become terminal landscapes because the vampire’s presence comes to represent the potential for death. More disturbingly are the realistic locales that UF authors select for their vampires to emerge from:

Crowded terraced houses blurred into unkempt semis with junk-filled gardens and peeling paintwork. Light spilled around half-closed curtains to pool on the pitted, uneven pavements. Graffiti-scarred tower blocks thrust into the night sky like giant tombstones and here and there houses squatted like waiting nightmares, their windows shuttered with blank steel plates. Sucker town in all its midnight glory. 24

These places in a state of decay are already tainted by the terminal. It is believable that the edges of a city that experience crime and social problems are the perfect hunting grounds for all types of monsters. These terminal landscapes are atmospherically emphasised by the use of dark imagery—the vampires emerge from shadows and out of darkness. They belong to the night—a time considered dichotomous to life and light. UF authors depict their creatures in caverns, sleeping underground (Hamilton) or in abandoned houses surrounded by the ghosts of those they have killed (as in Patricia Briggs’ series Mercy Thompson). For UF, the terminal landscape and undead are irreducibly linked because each functions to further the imagery of the other.

The terminal landscapes developed in a living city aid in the atmosphere of fear and dread. Many of the liminal spaces are situated in terminal landscapes, which are places in a state of decay or abandoned/forgotten locales. However, unlike the below of a city, a terminal space is implied as any place touched by the dead. This opens up all the traditional safe zones of a city (such as homes, sacred spaces and places of authority) to the threat of the dead, thereby creating invasive terminal landscapes—for who can escape death? The emotional weight of a terminal landscape contributes to the development of UF’s thematic concerns. The physical locales associated with the transition of dying are tinged already with fear and dread. For although people may come to accept death, they have not accepted the process or its presence in modern life. The locales of the dead are touched by a mix of emotional worship, loss and grief. However, the deep pain of loss is often negated by a final acceptance of the permanency of the state. By introducing the undead to such static places, UF authors are subverting and somewhat perverting these places. This creates a terminal landscape of liminality where the end point has become unclear because, even though zombies may be laid to rest and vampires ‘die’ in the day, the mythology of UF allows these creatures to rise again in the same space. This notion evokes an unsettling sense of dread.

The mythos connected to raising the dead already occupies a place of deep unease in Western Christian society. Connected from a Christian view to the story of Jesus and the saints, it appears in UF as a strong perversion of divinity. The other legends of the dead rising commonly used in fiction today derive from Vaudun or voodoo traditions. Every culture, religion and time has a set of beliefs regarding the ability to raise the dead. It is a fundamental desire of humankind to be able to find a way to restore our departed. UF appears to primarily maintain that the ability to raise the dead comes either from the process of vampirism or a personal ability of necromancy. Regardless of a particular UF’s mythology, the result is the presence of the undead, whose very unnaturalness upsets the balance of the world. With a focus on the undead or death in various forms, UF requires the presence of terminal landscapes where characters face horrors dichotomous to natural life. The dread evoked by these places in the reader is furthered by the accompaniment of blood and violence.

For UF characters and readers, the city is now a place of unrelenting fear. The urban landscape are commonly based on, and in, real world cities where the terrible intersects with the everyday. The settings are recognisable to any city-dweller, as are the moments of potential terror, evoking an uneasy anxiety. For what is more terrifying than to realise we might too be victims of the monsters in our city?

Works Cited

- Attebery, B. (2008). Introduction: fear and fantasy. Journal of the Fantastic in the Arts, 19(1), 1-4. Retrieved from http://go.galegroup.com ↩

- Cavallaro, D. (2002). Gothic vision: Three centuries of horror, terror and fear. New York, NY: Continuum, p. 6 ↩

- Lovecraft, H. P. (2004). Introduction to supernatural horror in literature. In D. Sandner (Ed.), Fantastic literature: A critical reader. Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers. p. 105 ↩

- Briggs, P. (2009c). Moon Called. London, England: Orbit, p. 123 ↩

- Cavallaro, D. (2002). Gothic vision: Three centuries of horror, terror and fear. New York, NY: Continuum, p. 7 ↩

- Cavallaro, D. (2002). Gothic vision: Three centuries of horror, terror and fear. New York, NY: Continuum, p. 7 ↩

- Cavallaro, D. (2002). Gothic vision: Three centuries of horror, terror and fear. New York, NY: Continuum, p. 7 ↩

- Cavallaro, D. (2002). Gothic vision: Three centuries of horror, terror and fear. New York, NY: Continuum, p. 8 ↩

- La Shure, C. (2005). What is liminality. Liminality: The space in between. Retrieved from http://www.liminality.org/about/whatisliminality/ ↩

- La Shure, C. (2005). What is liminality. Liminality: The space in between. Retrieved from http://www.liminality.org/about/whatisliminality/ ↩

- La Shure, C. (2005). What is liminality. Liminality: The space in between. Retrieved from http://www.liminality.org/about/whatisliminality/ ↩

- Mieville, C. (2011). King Rat. London, England: Pan Books ↩

- Mieville, C. (2011). King Rat. London, England: Pan Books, p. 34 ↩

- Mieville, C. (2011). King Rat. London, England: Pan Books, p. 102 ↩

- Mieville, C. (2011). King Rat. London, England: Pan Books, p. 103 ↩

- Mieville, C. (2011). King Rat. London, England: Pan Books, p. 106 ↩

- Mieville, C. (2011). King rat. London, England: Pan Books, p. 206 ↩

- Mieville, C. (2011). King rat. London, England: Pan Books, p. 103 ↩

- Mieville, C. (2011). King rat. London, England: Pan Books, p. 119 ↩

- Mieville, C. (2011). King rat. London, England: Pan Books, p. 193 ↩

- Mieville, C. (2011). King rat. London, England: Pan Books, p. 338 ↩

- Lehan, R. (1986). Urban signs and urban literature: Literary form and historical process. New Literary History, 18(1), 99-113. doi:10.2307/468657, p. 105 ↩

- Hamilton, L. K. (2007). Guilty pleasures. London, England: Orbit, p. 249 ↩

- McLeod, S. (2009). The sweet scent of blood. London, England: Gollancz, p. 132 ↩

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Love the genre. I recommend Christopher Moore’s work who has a comedy vampire trilogy set in San Francisco: Blood Sucking Fiends: A Love Story, You Suck, and Bite Me.

While I enjoyed book no. 1, book no. 2 is still waiting for me to finish it, and I cannot see this happening any time soon.

I like Moore, don’t get me wrong. But his vampire trilogy are not the best of his books.

I liked A Dirty job much more (have just seen there is a second book to that) – and Practical Demonkeeping … But his best was Lamb: The Gospel According to Biff, Jesus’ childhood pal.

I only ever read the first one of that trilogy and no other of his books. An escape from the total Gothic vampire would be nice occasionally.

I too have enjoyed some of Christopher Fowler’s novels- I think they sit happily in this genre.

Ben Aaronovitch’s Rivers of London series is a must read. It has a black hero making it not very mainstream though.

The USA is a big market, and its underlying racist streak has become very apparent over the last year. That’s a lousy reason for changing a character, but it is there. It’s also dangerous. We’re not that much better here in England, even without the residues of slavery. My own experience suggests that for many of us the UK’s coloured population is still too new for us to be comfortable.

One of the reasons I love the Rivers of London series is because Aaronovitch included PoC living in the city. A lot of writers forget to add them. I also really liked Gaiman’s Anansi Boys.

Kate Griffith’s Monsters Anon series has a protagonist of Asian descent. I really enjoy that series.

I came to love this genre. A big thank you to all authors of such material.

Has anyone read the Benedict Jacka “Alex Verus” novels? Admittedly I am a bit biased as they seem to be set in all of my old stomping grounds around Camden Town and I love spotting my old haunts! But I love the premise of magic as something logical and scientific-ish that is happening all around us. It is just that most of us just can’t see it. His friend Arachne is one of the best Urban Fantasy creations too. I can’t get enough of her but I am pretty sure I wouldn’t want to meet her face-2-face!

I like my fix of UF books. Most of them I’ve read contain large doses of horror, dealing as they are with monsters most of the time who cause much bloodshed and destruction.

I’m an aspiring UF writing and I’ve always liked the idea of America splitting, with one area becoming a series of city states who, more or less, rule themselves. Gives you a great deal of freedom.

The thing with urban fantasy is the juxtaposition of the real and the fantastic. The mundane and the magical.

My urban fantasy novel, Fringe, is set in New York and Toronto–because I’ve been to both a half-dozen times, and have wandered the streets of both after midnight trying to get back to my hotel. I’d also allow myself to write a novel set in D.C., Vancouver, Edmonton and Dubai, given my familiarity with the cities.

I think that a cool way to do an Urban fantasy is with a city that was founded a long time ago, but has modernized with the times! Think a lot of old European cities.

I like the contrast of the modern concrete jungles and ancient catacombs, new tech and old magic, all that. There’s something compelling about a modern city built upon an ancient one.

Thank you for the afternoon read. A big part of the point of the genre is the clash between the fantastic and impossible and magical… and the normal, the real, the familiar. You can play that clash in a variety of different ways depending on the story, setting, and tone- from Comedic relief to Horror to deeply personal drama and all sorts of fun stuff, but the crux of the genre is about putting impossible, magical ideas and events and people and creatures into an otherwise familiar and easily-recognizable world, leveraging what your audience knows about real life to your advantage, both to fill out bits of the setting, and to emphasize the supernatural elements to give them more kick.

I love Ben Aaronovitch’s Rivers of London series because you can see how much he knows and cares about the city: what lesser-known places there are, what different parts feel like, how the people tick, how they live, etc. I think that’s something you can’t just learn by using Google Earth.

Thanks you for a great article. I’m a discovery writer and my current work in progress has quite accidentally propelled me into the urban fantasy genre. I’ve been trying to wrap my head around the question of what genre my story has become. This helped!

Me too! I wasn’t sure what my category my new story would fall into until after I read this. Thanks for sharing!

Any great UF recommendations?

The Walker Papers by C.E. Murphy

Jane True series by Nicole Peeler. It is, by far, the funniest urban fantasy series I have read.

The Nightside series from Simon R. Green.

Simon Green’s Secret Histories series is really fun.

The Kate Daniels series by Ilona Andrews. By far a favourite of mine, right there with the Night Huntress.

I would recommend Ilona’s Edge series, and it’s a complete series.

The Dresden Files by Jim Butcher,

The Iron Druid Chronicles, by Kevin Hearne.

There are in a sense two genres of urban-fantasy fiction.

One – the usual cast of were-types, zombie-types, computer/android types and vampire-types, set in some futury-dystopia-type world that, as the episodes continue, gets less and less “other” and more and more like present suburban America, as do the characters.

Two – all sorts of uncategorisable stuff, and people and things, not necessarily reducible to first-world contemporary culture tarted up a bit.

Neil Gamain’s writing contains both. China Mieville’s gets more strange and brain-stretching. There are other writers out there but, because they don’t write the familiar “types” and tropes immediately recognisable to marketing executives, they will never be made into TV shows or games (not that this is the aim).

True. A commercial genre and a literary space for weird experimentation. I like both!

I think some of China Mieville’s stuff could be the source for some grand television. Or awful SyFy cgi dreck but either way he’s a writer certainly has scope for a long form tv adaptation.

I don’t think anything by China Mieville is filmable. Except maybe Un Lun Dun, or Kraken. New Crobuzon is all about the description.

London has surely become the modern home of Urban Fantasy novels.

The last thing the fantasy genre needs is another medieval soap opera masquerading as fantasy.

Much as I love urban fantasy, there is an awful lot of were-sex, possibly for those with where-sex?

I lay the blame for urban fantasy descending into shapeshifter and vampire pron squarely on Laurel K. Hamilton. Largely a good writer with an appealing premise, she discovered that sex sells and never looked back.

Cucc, surely it goes back to Anne Rice in terms of sexualisation. Though, some have noted that even in the Victorian period, vampires were always ‘all about foreplay’.

I feel like American cities are best suited for urban fantasy because you can have so many different mythologies interacting with one another in one place.

South and Central America could also fit for the same reasons!

I have to share a series I read that I totally LOVED!! If you want a fun, quirky and imaginative series whose characters stay with you for a long time [in a very good way!] try R.L. Naquin’s Monster Haven series!!! Just brilliant!!! 😉 Also, Pippa daCosta has a few small series that are well worth a read, including the Veil Series!!

I always love New England as a setting. There’s something so creepy about Puritans and witch hunts. There’s a reason Stephen King and Lovecraft both use NE frequently!

I’m in the midst of a new novel about a re-imagined Los Angeles, transformed by a wayward revolution against the past and this article is super handy. Thank you.

The stereotype is that most of the authors in urban fantasy are female, whether the good writers like Emma Bull and Seanan McGuire or the hacks cranking out sex-with-were-leopards commercial extruded fiction product.

I really like the horror angle in urban fantasy and it should not be underestimated. As most good UF stories deal with monsters of varying shades of darkness, horror inevitably becomes a major focus, unless of course the story is really paranormal romance, in which case the horror will be played down a great deal. Most of the best UF books I’ve read have been quite dark and haven’t flinched from the horror these monsters inspire, and indeed cause within the story.

For me, the best thing about urban fantasy is how real it feels. The setting is so mundane and normal It makes the fantasy elements that much richer because they are in the real world.

I’d love to read more about how urban fantasy maps on to our current anxieties in the USA in particular. Our whole world feels liminal these days, very uncanny and unstable.

I really love Jim Butcher’s Chicago-based Dresden Files.

Nicely done and thank you for an interesting read. During the late 1970s I spent some time in Hong Kong. The city of Kowloon was monstrous to me – noisy, smelly, dirty, oppressive, dangerous (in some areas) and permanently on the go 24/7…and yet in a strange way I loved it.

Love the discussion of terminal vs. open spaces, and the ideas that readers are drawn to the stories that invoke their darkest imaginings. The same is true for writers, too. I’m a writer working on her first dystopian-type project. I’ve never even liked dystopia, but my main character showed up and said she was living in 2133 as part of a minority group, so have fun with that. Sometimes I wonder exactly why my mind wants to go the places it goes when creating fiction. Maybe this is why.

Very provocative topic combined with outstanding writing. I would have preferred the title “Monstrous City: The Urban Fantasy Domain” for greater impact and to draw the reader in. But, I suppose it’s fine the way it turned out.

#wow

I was very intrigued by your paragraph explaining how dread bring out curiosity and anger at the unknown. It relates to how human nature will always need closure or at least a sense of it in everything.

I learned a lot more about urban fantasy, thanks to your article!

You’ve done a very detailed excavation of the UF genre! I especially like your mention of liminal spaces. I think something interesting about urban representation in fantasy is perhaps, as you mentioned, the connection to real-life anxieties. You mentioned people who are outsiders and literally on the outskirts, and how horror translates into portraying these marginalized people as something to fear. We see this a lot with people who have disabilities in fiction. You also mention sewer systems and underground systems, and Jordan Peele’s US portrays the Tethered as existing underground, literally being hidden away under everyone else until they choose to rebel and ascend.

I think a city is often representative of very strong racial and class-based tensions. The presence of the vampire in these scenarios is complicated, because though many representations of vampires in fiction show them to be oppressed (or disadvantaged because of blood hunger, sensitivity to sun, appearance like the Nosferatu in Vampire: The Masquerade), traditionally vampires are aristocratic and wealthy, even in modern fiction (Edward Cullen, Bill from True Blood). So, portraying certain supernatural entities in an urban setting introduces the possibility to explore complicated dynamics.

An interesting essay, well developed and enjoyable to read.

I see a sort of return to the primal in such dystopia. Reminiscent of Cyberpunk.

To me, the most fascinating thing about the Urban Fantasy genre is the quirk of worldbuilding sometimes called the Veil: in a lot of UF, regular humans are not allowed to know about magic and magical creatures, either because of a law (as in Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them) or some kind of spell that erases magic from humans’ awareness.

Imagine if other fantasy worlds, like Middle-Earth, had this trope. Stories would be very different if one of the racial groups was almost completely unaware of the existence of every other racial group. Themes of prejudice and cooperation would be a little different, too.