Story Telling and Interactivity in Video Gaming

Gaming is nowadays an industry with varying forms and types 1. This article is particularly interested in video gaming, and how the medium has changed in terms of story telling and interactivity. This article is also focused on how the medium affects the experience, this being of the player. Video games have especially seen a significant development since 1972, when Magnavok Odyssey began being sold on retail. The Magnavok Odyssey was essentially a Pong console, which were popular in the 70s until the arrival of the Atari 2600. This was a console released in 1977 and lay the foundation for games to have characters, minimalist but simple plots, and player interactivity 2.

In terms of Interactivity and Story Telling, and particular to this article, all games mentioned or discussed will involve games released after 1977 (i.e. after the release of the Atari 2600). This article, however, will focus on games released between 1991 and 2002, and cover games based on depth put into story. All this is irrespective of genre such as Real Time Strategy (RTS), First Person Shooter (FPS), Role Playing Game (RPG), and Turn Based Strategy (TBS). This article does not cite sport games as having a story telling component. This game will also not discuss text-based video games, as an article on The Artifice already discusses that topic.

A background is necessary in order to understand the core concepts of both Interactivity and Story Telling from a video game perspective. After this, examples of games which are either influential, unique, or revolutionary in their approach will be provided. Details pertaining to the games themselves will only be provided if it helps with the question this article is attempting to answer.

What is Interactivity?

Interactivity is, in the most simplest of terms, a term used to describe how the player experiences the story, mechanics, and environment of a game. There are numerous discussions on the topic of Interactivity in Video Games, and some of these are available on Youtube. Interactivity has changed significantly since the arrival of the Atari 2600, and this is due to the introduction of new means to make the experience of a game likely, involved, and interesting. This is balanced with making sure that the game itself does not force players into suspending disbelief. These are necessary so as to prevent players from becoming disillusioned by the game and therefore choosing to stop playing it 3.

The simplest example of Interactivity reverts back to the Atari 2600, in which games were developed for home consoles to emulate the same experience as if in an arcade. Because they had to be simple, having low learning curves, and adaptability, these games are the prototype from which developers would learn or adapt their end product 4. Some frequent examples include Pitfall, Enduro, and Frogger.

Interactivity has, however, developed significantly since Atari 2600’s lineup of games. Most successful and influential titles (e.g. Best PC Games: Editors’ Choice Games Reviewed by IGN) are now expected to have well developed environments, industry standard music (if not better), and character models which are imaginative, but identifiable. Interactivity also determines which game mechanics are standardized based on game genres. These mechanics tend to become tropes in their respective genres. This can range from the regenerating health mechanic courtesy of Call of Duty games (post-Modern Warfare), the turn-based system of fighting courtesy of Final Fantasy, and the use of quick time events (QTE) courtesy of God of War (although Dragon’s Lair, a 1983 arcade game later remastered for the PS3/PS4, was the first to introduce QTE).

If the interactivity of a game is difficult, cumbersome, or insufficient for a player to invest in a game, then it may result in the game becoming known only for those qualities more. One very infamous example is E.T., an Atari 2600 adaptation of the movie of the same name. It is notorious for its unresponsive control scheme, unexplained gameplay mechanics (for those playing it on an emulator or on a console without the manual), and use of pitfalls, as well as being a cause for the 1983 North American Video Game Crash.

It is therefore important for interactivity in games to be easily contextualized by a gamer. However, interactivity is one of the qualities which defines how successful a game is. This is where Story Telling comes in.

Story Telling

Story Telling is, in other words, the narrative structure of a game. It involves the same questions which arise when purchasing a book: what kind of story will it tell? How good are the characters? Is the plot memorable? Is the environment engrossing? All these questions are as important to a video game as they are to a book. When successful, the inspire players to have discussions and learn new concepts and ideas. With the arrival of the Super Nintendo, SEGA Genesis, Playstation One, Game Boy, and improvements in PC gaming technologies, it became a necessity to have stories that were able to stand on equal grounds with interactivity in-game.

In terms of story telling, games which are cited as being influential include The Legend of Zelda, The Last of Us, Bioshock, The Walking Dead, Dungeons and Dragons: Shadows over Mystera (a 16-bit arcade game made by Capcom), Bloodborne, Max Payne, Deus Ex and Wing Commander. All of them are important because their interactivity makes the story – the plot, the characters, the environment in-game – more tangible. Therefore it incites discussion, while at the same time being entertaining entities. Some of these have been discussed for their literary qualities, such as Bioshock, The Last of Us, Ultima 4, and Deus Ex to name a few.

This is because games have, from second generation consoles – or from 1994 onwards – put emphasis on their stories as well as on concepts of “player involvement” and “the illusion of choice”. As a result, games are not only an exercise of good interactivity, they are also a test of how strong their stories are and how effectively these stories have been told. Many elements from these stories have, by themselves, become iconic in the industry. The use of object descriptions to help piece together a story, as Bloodborne uses, is one such example. Another is the “finding and combining the four elements of earth, water, air, and fire to fight the villain” story, which was made iconic by Final Fantasy III. These game stories are iconic because the stories were incorporated into the games themselves, whereas games released prior relied heavily on their manuals and addentum of reading material (such as Ultima 4).

With Interactivity and Story Telling explained, to a reasonable extent, this article will now proceed to show how interactivity and story-telling in video games affect the player. Before each game selected, a contextual perspective will be given as to why the game itself was selected. All games selected will answer the following three questions: what do players experience during the game, how does this experience affect players who have completed the game, and will this experience be considerably influential for players?

Beneath a Steel Sky (1994, Revolutionary Software, PC)

Beneath a Steel Sky is a 1994 PC Game released for MS-DOS. It falls under the Point-and-Click Genre and has been remastered for the PS4 and XBoxOne. It is influential both because it is an example of how interactivity – music, character development, player choice, and player immersion – were first integrated into a game, while also holding a competent story, and well developed pacing.

Context

Beneath a Steel Sky belongs to a genre called Point-and-Click games. Prior to Point-and-Click, games were either arcade games with minimal graphics (such as those from the Atari 2600 era), or were defined genres whose stories were published in manuals to be read by the player. The latter still hold true for games published in the fantasy genre (such as Witcher 3). In between, a trend towards text-based games had also started, in which the game is composed of text and – like a traditional RPG – the game progresses through specific actions. While it did not last long, it did inspire the Point-and-Click genre significantly.

Point-and-Click games are unique because they only require a mouse to control the protagonist, and other characters involved in the story. Games released after 1998 would integrate both the mouse and keyboard; with the advent of Steam and HD Remastering, these games would also be adapted for XBox and Playstation controllers. They have an inventory system in which puzzles are solved using a specific object. At the same time, they also have story-telling elements as item descriptions hint either to the progression of the story, or the progression from scene to scene. Point-and-Click games are also important to mention in terms of interactivity because dialogues are dependent on the type of questions which are asked by the player 5.

While point-and-click games are simple examples of interactivity – this being due to the simple mechanics layout which has generally remained consistent and standard – it is through the story that the game in itself becomes identifiable. Among the first games to have been released in the Point-and-Click genre include 1987’s The Shadowgate but the most popular and most significant include The Secret of Monkey Island (1990), Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis (1992), Gabriel Knight: Sins of the Fathers (1993), Under a Killing Moon (1994), I have no mouth and I must scream (1995), Blade Runnner (1997) Grim Fandango (1998). and The Longest Journey (1999). These represent the first generation of Point-and-Click Games 6.

Beneath a Steel Sky was selected, bearing in mind the above context especially. However, there is more involved with the game, as will be discussed shortly.

What do the players experience during this game?

Of all the games produced by UK studios year upon year, the most quintessentially British might forever be Beneath a Steel Sky. Simultaneously delicate, sophisticated, campy, and melancholic, it’s also a great interactive comic book. Its point-and-click action, peppered with cut scenes by Watchmen artist Dave Gibbons, makes it one of the most fondly remembered and revisited of the early 90’s adventure games. (From Tony Mott’s “1001 Video Games You Must Play Before You Die: You Must Play Before You Die”)

This game features standardized point-and-click approaches – the main character is in a single scene, and thus must scroll the mouse around the room until they find something to perform an action with. That action is determined by how close the protagonist is to the object, or if the object requires a key or a component to function properly. The point-and-click adventure games, knowing that the game itself did not have the player actively controlling its action scenes – and this is a significant aspect here in Beneath a Steel Sky – invest a significant portion of their gameplay towards character development. As a result, the player experiences the protagonist, the characters, and the environment with more detail, and thus it plays like an interactive mystery/puzzle piece 7. For this reason, Beneath a Steel Sky is a very linear game, with a concrete story told through an independent protagonist from beginning till end. It is also important to mention because it proceeds from beginning till end, rather than the in media res approach which most stories in games tend to follow. These include The Order 1886, Max Payne 2, Final Fantasy X, and God of War.

Beneath a Steel Sky however, does afford replayability. The point-and-click approach means that some portions have significant player choice opportunities. As a result players, regardless of the linear story, are given subtle moments whereby they watch the protagonist and other characters – major and minor – develop and grow organically. They also afford opportunities for the game to present its brand of humour, for which it still is cited as influential 8.

How does this experience affect players who have completed the game?

The game Beneath a Steel Sky is composed of British humour, dry wit, and significantly serious plot twists. As Dave Gibbons was asked to make cut scenes for this game, it also has many dark over- and under-tones. However, these are expressed subtly, rather than succinctly. This is a quality which works in Beneath a Steel Sky’s favour – while it may not have a significant variety for player choice, it makes up for it with a very fluid player control experience. It also has a very high replay value, because the characters themselves, such as the protagonist Robert Foster. It is also notable because the environments, combined with the subtle story telling technique used, makes players laugh the first time they played the game – the interaction between all characters in this game is laced with good humor – but appreciate the game’s narrative and plot once completed 9

.

Will the experience be considered influential for players?

This aspect goes without saying. The point-and-click adventures, having seen a resurgence, brought about by games such as Skyrim, The Witcher, Mass Effect, and Red Dead Redemption, as well as Android/iPhone technology, has made them more popular over the years. This especially applies to Beneath a Steel Sky. The use of sound and music in this game improve the narrative and story-telling component of the game. It is also pertinent to mention that Beneath a Steel Sky, unlike some of its notable counterparts such as I Have No Mouth and I Must Scream, handles its subject matter lightly. These aspects significantly help in the overall experience, and have been cited as being crucial from a story-telling in video games perspective 10. It is therefore, a cross-generational experience whose influence has only increased over the years, and especially because of the Internet and Android/iPhone and Modern Console technologies.

Chrono Trigger (1995, Squaresoft, SNES/PSOne/NDS)

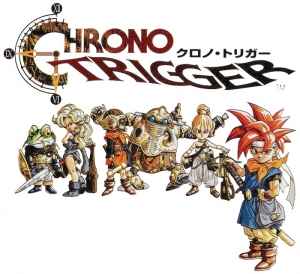

Chrono Trigger is a 1995 Square Enix title which was first released for the SNES, and then ported onto the Nintendo DS and PSOne. It is a TBS Japanese Role Playing Game (JRPG) which has a significant and memorable story arc, an ingenious gameplay mechanic, and is considered significantly influential in terms of its development of in-game environments for Japanese RPGs and TBS RPG in general.

Context

Japanese Role Playing Games (JRPGs) had gained a foothold from 1986 onwards, although it was 1989’s Phantasy Star II which helped to make it a staple as a genre. In the context of this article, although JRPGs have a notable interactivity element, it is the storyline aspect which makes them important.

Most of the notable JRPG titles that are included in Recommended Gaming Lists e.g. IGN, have staple interactivity elements: there are more than one protagonists in the story; the protagonists can be given different names by the player; there is a standardized system of improving character attributes (standard being Strength, Dexterity, Intelligence, and Stamina) through defeating bosses or a certain number of enemies per level; availability of different weapons and items, which either improve the character or develop the story; and side quests. The stories tend to range from very memorable, as has been the case with Phantasy Star II, Final Fantasy IV, Final Fantasy VII, and Kingdom Hearts, to notorious, such as Hydlide, Castlevania: Simon’s Quest and Final Fantasy XIII, to name a few.

Although JRPG and Point-and-Click both featured good storylines, the latter is dependent on a predetermined story-arc whereas the former will allow the player to take the role of the silent protagonist. The former, therefore, has the options of multiple endings, whereas the latter is story driven. This is particularly interesting to mention: even though in both cases, interactivity with NPCs is a significant part of the story, JRPGs take steps from Point-and-Click games and expand on it. Thus why JRPGs have multiple endings. Also, unlike Point-and-Click games, they are Turn-Based-Strategy (TBS) system based.

Chrono Trigger was released in 1995, and was significant in the development of the JRPG genre, as well as TBS. Further details regarding the game itself are provided below.

What do the players experience during this game?

Chrono Trigger is a TBS RPG game, with some significant and influential aspects included. Unlike previous games, in which NPCs did not have a significant role other than progressing the story, Chrono Trigger puts emphasis on player choice. Although the name of the main protagonist is Chrono, it can be altered at the start of a game – an RPG trope common to TBS RPG games released by Squaresoft (now SquareEnix). this is illustrated from the carnival segment of the game, a portion that has become iconic for this game 11. That scene, combined with other important (but spoiler ridden) aspects of the game itself make it an experience for gamers – they are not only playing the game, but are also involved in how the game will end 12.

Whereas Beneath a Steel Sky in the context of this article put emphasis on the story of the main protagonist, Chrono Trigger has notable side-characters and minor characters all of whom not only can be interacted with, but also emphasize a non-linear approach to the game resulting in multiple endings. The player, therefore, experiences the characters as projection protagonists – they play the characters as themselves and thus decide how the game should end. Chrono Trigger also benefits from an inspiring score that manages to describe the story, the characters, and the general interactivity through its composition.

How does this experience affect players who have completed the game?

Chrono Trigger is one of the best video games ever made. A universally cherished role-playing game, it was originally released for the Super Nintendo in 1995. Its creation is the stuff of legend, as it was developed by a dream team of the most talented RPG makers of the 16-bit era, all coming together to work on this one epic project. (Lucas M. Thomas, IGN Editor)

Fans and casual players of the game have found the experience of Chrono Trigger immensely satisfying. Because of the use of time-travel, the core plot, as well as the easy-to-learn fighting mechanics of the game, it has constantly been included in top 100 games of all times lists. There are also reviews on the game as a whole, but rely on the three points that make the game itself a classic: its main character Chrono, its battle system, and it being the first to introduce “New Game+” as an option. In some respects, Chrono Trigger is also successful and beloved because it is a single title, whereas Final Fantasy is a complete universe of its own and other JRPG games have multiple entries in their roster. Chrono Trigger, being a single game, is a complete experience, and is an experience which affected players in a positive way. They learn the values of chivalry, honesty, and even loyalty in friendship because these themes are extensively integrated into the game itself. What this means is: in Chrono Trigger, the interactivity of the player with other NPCs affects how the story progresses and changes. This is best described by the Trial Scene – without going into too many spoilers, in the beginning of the game, all actions performed in the carnival are questioned, and the answer to the questions affects not just the ending of the game, but the interaction between NPCs.

Will the experience be considered influential for players?

It goes without saying that Chrono Trigger has become an embodiment of an era, that of the 16-bit generation of games. It has been cited consistently from modern games like Undertale, through to From Software, with their 1999 title Echo Night (an obscure first person based puzzle and mystery solving game). The aspect of “New Game+” is also integrated into most, if not all, modern games, and has been especially prominent for games such as Dark Souls, Bloodborne, and Shadow of the Colossus. The themes explored in this game are also inspirational, because of the importance given to player choice. Because the game as a whole is non-linear in terms of interactivity, but linear in terms of gameplay, the multiple endings also instil involvement even after the game’s age of nearly 20 years. Chrono Trigger would also emphasize the need to have competent stories, at a time when stories in games were simple, straightforward, and often considered padding.

Context for both Soul Reaver and Silent Hill 2

While Point-and-Click Games and JRPG have had their trends and timelines, the categories of platformers, hack-n-slash and traditional third person 3D movement became popular with the advent of the Playstation, Nintendo 64, and PC.

The most well known example of a platformer is Super Mario Bros for the NES, released in 1985 as an original part of the console. Other titles which are included in the platformer genre include the original Atari Pitfall, released in 1982, and Prince of Persia for Microsoft Disk Operating System (MS-DOS) released in 1989, and Sonic the Hedgehog for SEGA released in 1991. All these are examples of 2D platformers, and only Prince of Persia had a full fledged story – the rest of these games retrospectively developed their stories, or went without them altogether. This aspect made such games, even today, easy as a concept but difficult as an implementation device – it is for this reason that the genre has very easily identifiable interactivity elements 13. Most platformers also became useful in developing the hack-n-slash genre.

Hack-n-Slash is a term which refers to either RPG style games in which the player uses physical or magical strength to reach the end of a level, employing very basic story-telling. Or it refers to beat-em up games, which arose as a result of this type of interactivity. Beat-em Up Games include the classic Golden Axe trilogy, Streets of Rage trilogy, the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles games for NES and SEGA, and Metal Slug for the NEO-GEO 14. Like the previously mentioned platformers, these titles are technically 2D based, and like Prince of Persia used a very basic story-telling element.

However, with the advent of JRPG, the introduction of full-motion video (FMV) through PSOne and Sega CD, and with 3D polygon technology, both platformers and hack-n-slash genres were often conjugated together. As a result of JRPG and also because of Point-and-Click games, story-telling was considered a significant part of good games. This proved to be the case with Silent Hill, released in 1999 for PSOne by Konami; Spyro for PSOne in 1998 originally by Activision; Crash Bandicoot for PSOne released in 1996 originally by Naughty Dog; and Resident Evil 3 for PC, Gamecube and PSOne, originally released in 1999 (which was a marked improvement from the original Resident Evil). Silent Hill is a horror-genre third-person 3D hack-n-slash game; both Spyro and Crash Bandicoot are traditional platformer games; and Resident Evil 3 is a horror/survival third-person 3D hack-n-slash game. All of them use voice acting to varying degrees of success, while others

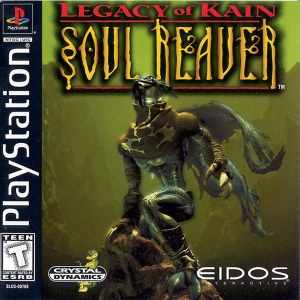

Legacy of Kain: Soul Reaver (1999, Crystal Dynamic and Eidos Interactive, PSOne)

Kain is deified. The Clans tell tales of Him. Few know the truth. He was mortal once, as were we all. However, His contempt for humanity drove him to create me, and my brethren.I am Raziel, first-born of His lieutenants. I stood with Kain and my brethren at the dawn of the empire. I have served Him a millennium. Over time, we became less human and more …divine. Kain would enter the state of change and emerge with a new gift. Some years after the master, our evolution would follow. Until I had the honor of surpassing my lord. For my transgression, I earned a new kind of reward… agony.

There was only one possible outcome – my eternal damnation. I, Raziel, was to suffer the fate of traitors and weaklings – to burn forever in the bowels of the Lake of the Dead. (Legacy of Kain: Soul Reaver, Introductory Cutscene)

Legacy of Kain: Soul Reaver, referred to as Soul Reaver by critics and fans alike, is a 1999 Crystal Dynamic and Eidos Interactive title released exclusively for the PSOne. It is a third-person platformer with puzzle solving components of interactivity, and mixes this with hack-n-slash and boss fights. It has been applauded significantly for its story, music, environmental design, and characters – particularly Raziel and Kain. Soul Reaver is the second in the series, succeeding Legacy of Kain: Blood Omen and a story sequel to Legacy of Kain: Blood Omen 2.

What do the players experience during this game?

Soul Reaver has been applauded and appraised consistently for its script, both in terms of writing and in terms of voice acting. Soul Reaver is unique because, unlike games released prior to it, voice acting tended to be seen as campy or incompetent. This is particularly the case with King of Fighters ’99 and Resident Evil. For this reason, the story of the game, combined with the environment, change in sound to emphasize a change in scenario, and the designs of the characters themselves, all help in making the voice acting a worthwhile addition to the game. It is also unique for having the same actors reprise their roles for future titles in the Legacy of Kain series. Tony Jay plays the role of The Elder God, Raziel’s mentor and the antagonist of Legacy of Kain: Defiance, as well as Zephon (a boss character in Soul Reaver). Simon Templeton reprises his role as Kain in this game, as well as voice act for Dumah (a boss character in Soul Reaver), and would continue to do so up till Legacy of Kain: Defiance. Michael Bell, a voice actor for 80s era animated series such as “The Smurfs”, “G.I. Joe” and “The Transformers”, plays the role of Raziel, as well as Melchiah (a boss character in Soul Reaver). And finally, Anna Gunn, who is notable for playing Skyler White in “Breaking Bad”, reprised her role as Ariel, and would continue to play the same role up till Legacy of Kain: Defiance.

Players are also treated to a few other qualities which made Soul Reaver unique for a PSOne game: the entire experience does not have a single loading screen save for the start of the game, the initial introductory cutscene, and the end credits. the environment of the game is, therefore, one fully loaded map around which Raziel, the protagonist, interacts to progress the story. Because of its competent voice acting, Soul Reaver is also able to provide an introductory level – to help players familiarize with the game mechanics and environment – which serves to amalgamate interactivity with character development and plot progression. This is particularly the case between Raziel and the Elder God, and were useful in laying the foundations for their interaction in Legacy of Kain: Soul Reaver 2 and Legacy of Kain: Defiance.

With that in mind, Soul Reaver has also earned a small amount of notoriety for its difficult puzzle solving component. First time players, from the perspective of reviewers, would find the initial exposure to puzzles either obtuse or difficult to complete. This is because of the use of both astral, and physical realms in order to solve puzzled and proceeding to the next stop in the game. The game does not provide any indication of this to the player, which does not interrupt the game experience but contributes to the difficulty in general. First time players are, therefore, advised to play this game with a walk-through guide.

However, Soul Reaver makes most use of the PSOne control, and was at the time of its release, a competitive example of “player control”. While Tomb Raider was amongst the first titles for platforming in 3D, Soul Reaver stands out because of its use of environmental cues, change in music, and depth of plot and character development 15.

How does this experience affect players who have completed the game?

Most players have found the ending cutscene of Soul Reaver a significantly influential cliffhanger, as well as an effective use of foreshadowing in future Legacy of Kain titles. However, because of the depth put into the game as a whole, especially the characters of Kain, Ariel, and Raziel, it has been applauded in how it established a series without relying on the trope of “obvious sequel baiting is obvious”. Soul Reaver is also commendable for revising the depth that both interactivity and story-telling can reach if balanced successfully, with Raziel providing the role of a narrator, as well as an independent protagonist. Almost all players have had a positive experience with Kain, who is a rarity in terms of Vampire depictions – he has motivations, a defined personality, and many of his quotes have become synonymous with the Legacy of Kain series as a whole.

Conscience…? You dare speak to me of conscience? Only when you have felt the full gravity of choice should you dare to question my judgment! (Kain, Soul Reaver)

The game is also an important landmark because of how it uses the ending of the first game, Blood Omen, to emphasize the change in Kain’s perspective. Both he and Raziel are embodiments of how the player feels in terms of betrayal, manipulation, and a general fear of helplessness 16. At the same time, they also illustrate how a competent story, a good environment, and an effective use of themes and concepts intrinsic to Vampires can be used more effectively. Soul Reaver, and the Legacy of Kain games in general, are a strong contrast to modern portrayals of Vampires, such as “Twilight”. Some articles believe it has to do with how Kain and Raziel are developed, especially when taken as characters 17. As a result, players experience a very effective story told using a well-placed, but fairly difficult and slightly irritating but effective gameplay mechanic and system.

Will the experience be considered influential for players?

The Legacy of Kain series became a reality because of Soul Reaver, and continues to be cited as an inspiration and influence in video games. It is unique amongst players because of how it used the Vampire mythos effectively. The use of a pre-loaded map to minimize load-times and use of load-screens is a mechanic that has been used in many third and fourth generation titles, such as Skyrim, Bloodborne, and Arkham City. The introduction of cut-scenes with effective voice acting and competent scripts is, nevertheless, the most significant influence of Soul Reaver. Because Simon Templeton, Tony Jay, Michael Bell, and Anna Gunn were provided effective scripts, and had prior experience with voice acting, Soul Reaver paved the way for many modern video games to work with actors in providing their talents. For example, George Takei for Red Alert 3, Liam Neeson for Fallout 3, Kiefer Sutherland for Metal Gear Solid V: The Phantom Pain, Kevin Spacey in Call of Duty: Advanced Warfare, Sean Bean and Patrick Stewart for Elder Scrolls IV: Oblivion, Samuel L. Jackson in Grand Theft Auto: Vice City, Mark Hamill as the Joker in Batman: Arkham City, and Elijah Wood in Spyro: A New Beginning, amongst a notable few major actors who have lent their influence to games.

The use of shift in music to indicate change in environment or a cue for a cut scene is also an integral influence brought by Soul Reaver. This has become almost integral to games, with examples of Skyrim being one prominent example.

Silent Hill 2 (2001, Konami, PS2)

Silent Hill 2 is a 2001 Konami title, the second to be released after 1999’s Silent Hill. A PS2 exclusive, it is a third person perspective horror/mystery genre game. It also remains to this day the most well received and deeply respected from the Silent Hill franchise. It is single handedly the most successful title from the Silent Hill series, Konami’s most influential entry in the horror genre, and amongst a handful few titles in the horror genre which are constantly cited for their effective use of themes, symbolism, and dark imagery to understand their protagonists. Some of these titles include Amnesia: The Dark Descent, Clock Tower, Penumbra, and Pathologic 18.

What do the players experience during this game?

Players take on the role of James Sunderland who leaves to Silent Hill to determine what happened to his wife. Silent Hill as a series has been famous for its use of the environment, especially the titular Silent Hills location, to explain the characters and their past. This was first reflected in Silent Hill 1, and unlike Silent Hill 2, would be used to more gruesome effect in subsequent games. Silent Hill 2 is unique because of its very protagonist centric story development, an element which has made it a unique literary analysis in itself 19.

Silent Hill 2, although not very well known for its voice acting, did produce a competent effort from its cast. The voice actor for James Sunderland, Guy Cihi, would later do voice acting for the game Mother. Donna Burke, the voice actor for Angela Orosco, also did voice acting for Claudia Wolf in Silent Hill 3, and is the voice of the iDroid in Metal Gear Solid V: The Phantom Pain. However, unlike Soul Reaver, Silent Hill 2 takes significant pride in being a minimalist game. Music is played only in select moments, if at all, and the only sounds heard are those of James Sunderland as he explores Silent Hill. Silent Hill 2 also uses audio to an effective extent, so that players are able to determine where the monsters (or rather, manifestations of monsters) will attack.

The most important experience from this game, however, is a character who has become iconic for the series: Pyramid Head. Pyramid Head is a central character in the Silent Hill series, and plays a significant role in establishing, from a story-telling standpoint, the crust of the problems that the protagonist faces. In the context of Silent Hill 2, he is the embodiment of fear and distress that James Sunderland must face, and why he should face them is at the core of the story. Hence, the player is determining why Pyramid Head attacks James Sunderland, and how to contain him 20.

How does this experience affect players who have completed the game?

Most players remember this game specially for its soundtrack, which include Promise (Reprise), Theme of Laura, and Maria’s theme. The success of this game is because of the ending, the phenomenal integration of player involvement and game interactivity, and the environment being in itself a plot device helping the progress of the story 21. Most players also found the character of Maria significantly integral to their experience of game, and this resulted in a Director’s Cut being released, which contained Born from a Wish. This could be considered the equivalent of a DLC, and helped explain the story through Maria’s perspective. Players were also treated to replayability because, per Silent Hill tradition, a casual playthrough of the game resulted in the “bad ending”. This ending has the main protagonist not learn from their mistake and therefore, forces the player into a position of disbelief. Silent Hill 2, technically, has six endings, inclusive of good, bad, and easter egg. However, all endings not only provide players with “player choice”, but all endings are effective from a story-telling perspective.

This is because the plot of Silent Hill 2 effects each player differently, and this is emphasized significantly by how much attention the player puts into the game itself. From the easter eggs, to the dark undertones of loneliness, betrayal, and depression, through to the maturity of James Sunderland depending on the player’s experience of the game, all influence how Silent Hill 2 affects the end product. At the same time, each playthrough also explains aspects which are referenced in other games, and put Silent Hill as a central environment of most Silent Hill titles (minus Silent Hill: Shattered Memories).

The most significant experience of this game, is Pyramid Head. There has been significant critical reception since he first appeared in Silent Hill 2, and his role in the context of this game also makes him an effectively employed manifestation of James Sunderland’s state of mind . Pyramid Head is also integral to mention because, prior to Silent Hill 2, Silent Hill was compared to Resident Evil and thus, with Pyramid Head they were able to remove that comparison and become their own entities 22.

Will the experience be considered influential for players?

Both Resident Evil and Silent Hill as gaming series, have become significantly downplayed. At present, Silent Hill as a series is on hiatus. This has become especially troublesome for Silent Hill because its creator, Hideo Kojima, had left Konami. While Silent Hill continues to be cited as an iconic game series, and Silent Hill 2 continues to be cited for its story, excellent use of interactivity, and in-depth perspectives of its characters (especially James Sunderland and Maria), it cannot help the series as a whole. Most critical reception since Silent Hill: Shattered Memories has been negative, especially for Silent Hill: Downpour. For players, it has become a heated point used against Konami, who are perceived by most as a money grabbing corporation and are often criticized, alongside Capcom, for making terrible executive decisions that will only break them rather than build them 23.

Silent Hill 2, nevertheless, continues to enjoy an avid liking by fans, enthusiasts and literary critics alike. While Silent Hill has tried to spread into other mediums, such as comics, these have been panned by some critics. The movies are also critical failures. However, regarding Silent Hill 2, there have been significant appraisals given for it to be as relevant at the time of its release, as it is now 24.

The use of multiple endings, as well as the dark themes discussed, in Silent Hill 2 would be used in other titles. They are more prominent, however, in Bloodborne and Dark Souls 2, where through interaction with other characters, item descriptions, and subtle cues in-game environments, the themes are fleshed out. This provides an opportunity for players to conclude and understand these themes, and make their own perspectives on them.

Conclusion

In all these mediums discussed, the type of interactivity and story-telling used has an influence on the player. Most of these titles are notable for being effective in their genres, as well as the choice of gameplay used. Furthermore, they are noteworthy for tackling themes or tropes in unique ways. Soul Reaver for instance, handled the Vampire mythos and genre in a theatrical format, with the environment being a living and organic entity. Similarly, Silent Hill 2 used the environment itself to help with the progression of the plot, as well as the development of its protagonist James Sunderland. Silent Hill 2 and Beneath a Steel Sky are also interesting as video game titles because of the way they handle serious themes: the former is more serious, albeit subtle and reliant on environmental cues and character interactions, while the latter uses player choice, character responses, and humour to inculcate the dark themes of its story. Chrono Trigger is notable as well, because like Beneath a Steel Sky and Silent Hill 2, the experience depends on player choice. Although in Chrono Trigger, player choice is a significant part of the gaming experience, whereas in Beneath a Steel Sky it is limited to dialogue choices, and in Silent Hill 2 it is limited only to the ending.

Modern games which are important and have been cited include Bioshock, Shadow of the Colossus, The Vanishing of Ethan Carter, and I Have No Mouth and I Must Scream, all of which are influential in their own forms and ways. Some of these games use interactivity and story-telling mechanics from titles discussed in this article. It is therefore, a positive attribute for a game, if its story-telling foundation – character development, plot progression, environment use – is balanced and (preferably) matched with its use of interactivity – music, competent voice acting, sound design, character design, choice of gameplay mechanic, and overall capacity to help in plot progression.

Works Cited

- Ryan, M.-L. (2010). From Narrative Games to Playable Stories: Toward a Poetics of Interactive Narrative. Storyworlds: A Journal of Narrative Studies, 1(1), 43–59. https://doi.org/10.1353/stw.0.0003 ↩

- Sousa, H. A. de. (2014). Writing for the player : adapting a traditional screenplay into an interactive format. Retrieved from http://repositorio.ucp.pt/handle/10400.14/16455 ↩

- Vorderer, P., & Bryant, J. (2012). Playing Video Games: Motives, Responses, and Consequences. Routledge. ↩

- Wolf, M. J. P. (2010). Assessing Interactivity in Video Game Design. Mechademia, 1(1), 78–85. https://doi.org/10.1353/mec.0.0095 ↩

- Vara, C. F. (2014, October). Creating Dreamlike Game Worlds Through Procedural Content Generation. In Seventh Intelligent Narrative Technologies Workshop. ↩

- Howard, J. (2008). Quests: Design, theory, and history in games and narratives. CRC Press. ↩

- Robert A. Shiels. (2008). The Genre that Mouse Built? How Culture, Markets and Technology Shaped the Rise, Fall and Resurrection of ‘Point and Click’ Adventure Games (MSc Multimedia Systems). University of Dublin, Dublin. Retrieved from http://robshiels.com/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2011/09/Adventure_Game_Dissertation.pdf ↩

- Ince, S. (2006). Writing for video games. A&C Black. Retrieved from https://books.google.de/books?hl=en&lr=&id=7gvM5hQjx8QC&oi=fnd&pg=PP1&dq=%22Beneath+a+Steel+Sky%22+AND+%22Influence%22&ots=5vI8WvYah5&sig=V46XXVCaYRYcbrVgvVgt5ukUgdg ↩

- Tringham, N. R. (2014). Science Fiction Video Games. CRC Press. ↩

- Lund, A. V. (2012). Sound and Music in Narrative Multimedia : A macroscopic discussion of audiovisual relations and auditory narrative functions in film, television and video games (MA Thesis). University of Oslo, Norway. Retrieved from https://www.duo.uio.no/handle/10852/34613 ↩

- Olson, C., Kauffman, D., Fowler, A., & Khosmood, F. (2015). Teaching Japanese through game mechanics: An exploratory study. In Sixth fdg Workshop on Procedural Content Generation. Retrieved from scholar-google-co-nz. ezproxy. aut. ac. nz. ↩

- Norman, F. (2011). ‘A peaceful world is a boring world’: a study in narrative structure and mythological elements in Squaresoft‟ s Chrono Trigger. Retrieved from http://www.diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid=diva2:401861 ↩

- Sorenson, N., & Pasquier, P. (2010, January). The evolution of fun: Automatic level design through challenge modeling. In Proceedings of the First International Conference on Computational Creativity (ICCCX). Lisbon, Portugal: ACM (pp. 258-267). ↩

- Garda, M. B. (2013). Neo-rogue and the essence of roguelikeness. Homo Ludens, 1(5), 59-72. ↩

- Sivak, M. (2011). Blocks, planes, drain, and kain: well played for legacy of kain: Soul Reaver. In Well played 3.0 (pp. 151–161). ETC Press. Retrieved from http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=2031872 ↩

- Valentine, L. J. (2010). Amnesiac Avatars–The Role of Memory Loss in Fantasy and Game. University of North Carolina Wilmington. Retrieved from http://dl.uncw.edu/etd/2010-1/valentinel/lennyvalentine.pdf ↩

- Romaneski, L. (n.d.). Legacy of Kain and the Digital Masculinities of Video Games. Retrieved from http://myweb.fsu.edu/lromaneski/midterm.htm ↩

- Kirkland, E. (2009). Storytelling in survival horror video games. Horror Video Games: Essays on the Fusion of Fear and Play, 62–78 ↩

- Kirkland, E. (2005). Restless dreams in Silent Hill: approaches to video game analysis. Journal of Media Practice, 6(3), 167–178. https://doi.org/10.1386/jmpr.6.3.167/1 ↩

- Zourgani, M. D., Lalu, J., & Weisser, M. (2016). Intermediality and Video Games: Analysis of Silent Hill 2. In Contemporary Research on Intertextuality in Video Games (pp. 54–69). IGI Global. Retrieved from https://books.google.de/books?hl=en&lr=&id=juR5DAAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PA54&dq=%22Pyramid+Head%22+AND+%22Narration%22&ots=sTk-vGAEqw&sig=Mhlr6NMSmotTUVRaGUbKnV6B1Oo ↩

- S̨engün, S. (2013). Silent Hill 2 and the Curious Case of Invisible Agency. In International Conference on Interactive Digital Storytelling (pp. 180–185). Springer. Retrieved from http://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-319-02756-2_22 ↩

- Perron, B. (2012). Silent Hill: The Terror Engine. University of Michigan Press. Retrieved from https://books.google.de/books?hl=en&lr=&id=vc9lzxnJpccC&oi=fnd&pg=PP8&dq=%22Pyramid+Head%22+AND+%22Narration%22&ots=hDrCGCLuf-&sig=iQ8nmVMt161os0lp3fn1-JdE8L8 ↩

- Hennig, M. (2015). Why Some Worlds Fail. Observations on the Relationship Between Intertextuality, Intermediality, and Transmediality in the Resident Evil and Silent Hill. Retrieved from http://www.gib.uni-tuebingen.de/own/journal/upload/8b67282882ef4efaf389cd1778a45101.pdf ↩

- Kirkland, E. (2007). The self-reflexive funhouse of Silent Hill. Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies, 13(4), 403–415 ↩

What do you think? Leave a comment.

If a games studio is given enough money, to put the time and effort into the storyline, the characters and construction of the virtual environment the gamer will be experiencing, there is no limit to what their imaginations can achieve.

Unfortunately, the fault lies not just with the determination and the technology of the company making the game, it also lies with the supporters / fans of the company.

No Man’s Sky, for instance. It promised a lot, but it didn’t deliver. THAT, is the claim of the fans, and something which I have noticed a lot of gamers make glaringly obvious.

In contrast, gamers had a middle line perspective on DOOM 2016. I personally LOVED it. I absolutely adore that game. However, I also respect the perspectives and opinions of those who actually thought it was repetitive, tedious, and even from a story-line standpoint, kind of pointless.

More to the point, its not about the money entirely. Its about manpower, determination, adaptability with technology. And generally how to improve or innovate the experiences of the gamers.

Again, that’s my opinion. Money should work in conjunction with imagination and technology, not as a predominant necessity.

One of the unique qualities of games is the feeling that you are driving the plot and dictating the action (even though you’re obviously not).

Its very true, because it is a power fantasy setting. You, the player, are aware that it is a power-fantasy. You are immersed in it, because you as the player understand that in the end, life in the game will not affect life in real life. So the effects are, at best, psychological. Maybe even spiritual depending on how good the game is.

But it has been put into another perspective as well. The false perspective, to the best of my knowledge, comes from games which believe in “save state killing”. DOOM 2016 actually used this technique, and it has been used in games released prior.

The concept is simple: At the highest and most extreme difficulty, if the protagonist dies, there is no extra life. They are dead, therefore YOU are dead. THUS, all trophies and achievements and all collectibles are gone. You therefore start from the ground up.

Bioshock Infinite also has such a mode. But its called 1999 mode.

Great article. This is a great publication. Any chance the author could have a word with game reviewers on other sites? Game reviews have been terrible for ages now, I’m complaining here because this article proves what this paper is capable of regarding gaming it’s just a shame the game reviews are so shockingly awful.

Unfortunately, I do not know any game reviewers anywhere. Not personally at the very least.

I’ve come to a conclusion that the best way to experience a game is if you hear about it from academic sources, or from very close friends / from family directly. OR, you went into the game blind.

The problem with games are, they don’t really lend themselves to “social context reviews”. This is because the world sees gaming the way we see things we don’t relate with: the whole us-and-them perspective.

I consider myself a gamer. I’ve played games on the following platforms (excluding PC): Gameboy Advance, PSOne, PS2, PS4, Xbox 360, SEGA Genesis, and NES. From the PC I wound up playing games through emulators for: MS DOS and SNES. Unfortunately, gaming is in and off itself, not AS big a community as, say… boxing, or snooker, or table tennis, or even simple cards.

And this is important to realize. Game Reviewers grew up playing traditional games, hell they practically only play traditional games. So if they are put in a situation where they should, for example’s sake, play Bloodborne, I don’t expect them to be very kind to it. Then again, when the game itself is made with good gameplay mechanics, the story has higher gears to fill in, and that works in its favor when its good (such as these games in my article mention).

New forms of narrative are certainly welcome. I think it’s worth making an actual distinction between games with good writing (of which there have been at least a few for many decades), and forms of writing with some non-linearity. The game/non-game distinction is useful for marketing, but not otherwise.

I don’t always agree with the non-linearity part to be honest. Somehow, being a traditionalist on story-telling structures, I hate it when I have to fill in the blanks by myself and make the story sensible or whatever. That’s lazy pathetic and sloppy work on part of the creators, and fans should know better than to fall into that trap. Unless the game itself treats the story like a badass, I will never tolerate sloppyness as a consumer, let alone a gamer, leave alone a fan.

I think the best example of a game which used non-linearity – which, by my definition, means that the story is not always a straight-forward approach with a clear climax and a conclusion structure to it – is actually DOOM 2016. the story is almost entirely bareboned. BUT, for me, it suits the attitude the game uses. And it uses its approach like a boss. Doomguy literally makes murder great again. And I’m eternally grateful for how DOOM 2016 handles his story.

All the same, to each their own. Bloodborne wasn’t my cup of tea. However, I respect people for why they would like that game. Its non-linear, yes, but it makes up for it through its interactivity, its environment, and all the cues and gameplay mechanics it uses to involve the player with the universe they play as the protagonist.

WOW! Awesome Article!

You dedication to researching and discussing this topic is awesome. This is such a great point of discussion and you have done an amazing job synthesizing the different aspects of video game storytelling and interactivity.

Gaming is really an exceptional medium and there are so many ways for game designers to create and tell a story. Gaming is an incredibly diverse medium and when people push the limits great stories and experiences are created. I feel that story telling in gaming is not given enough credit despite the fact that so many writers and game designers make such as amazing stories using in this medium.

My personal favorite ways to tell a story is through audio logs/files like in games like Bioshock. The deeper dive into the story/world is there for those who want to find out more about the world and its characters but for those who don’t want to dive deeper (those who just want to have some amazing gameplay!), they can just keep going with the game.

Amazing article! Thank you for creating such a great read!

Sorry for the late reply.

I thank you for your humbling comment. And you are right – there is plenty of underappreciation when it comes to story telling in video games. The medium is much more involved, although it boils down to the fact that habit prevents a person from actually thinking. Which is why we ignore the actual story.

Bioshock does that pretty well. It does have problems, but as a story it is bar none really well handled.

I don’t play games nearly as much as I used to but, for me, The Last of Us felt like a giant leap forwards in terms of marrying strong narrative and great gameplay.

It most certainly was. TLoU was one of those few games that made me feel what Joel felt, and the last action scene made me feel hurried and stressed without the requisite timer that most games feel is necessary.

Give Life Is Strange a try too. It’s not action oriented by any means, but details you pick up and remember can lead to drastic changes to how the game plays out.

Games are getting a lot better at telling stories but really the industry is still in its infancy in this regard and I think that there’s a tendency within the community to laud good examples excessively. Bioshock springs to mind – I love both games but some of the plot ideas are pretty undeveloped or on-the-nose (it’s an incredibly patriotic society? But they’re also a bit racist? What a groundbreaking idea!), yet this is often lauded as one of the shining examples of plot and gameworld.

Personally I think games often work better when the storytelling isn’t centre-stage, games like Dark Souls or Journey have the balance just right in my opinion. An engaging game world that encourages you to explore and creates an atmosphere that implies there’s more to find out if you want to. Obviously games are an interactive medium and I think it works better when more of the story is revealed as you put more into the game, which seems to me appropriate given that this kind of storytelling is unique to games. That’s just me though.

One of the text based games that I enjoyed was the Zero Escape series (so far two games with a third on the way). There are large passages of text, mixed with puzzle solving and ability to make decisions that affect the plot.

Interesting article, shared on FB.

Most games today lack what Chrono Trigger embodied. A great story, interesting characters where their abilities were unique (not the generic “character” where abilities are interchangeable with “skill points” or whatever a game decides to call it) and you cared about the characters. There are maybe a handful of games that were made in the last five years that I could see myself playing 21 years after they came out.

Games today are too generic and once their “newness” wears off no one will play them. They just keep making the same game with subtle updates.

Most RPG’s now are so complicated now you need a degree to play them and understand their plots or have no life (100+ hours for linear RPG’s, a lifetime for MMORPG’s).

I recently replayed Chrono Trigger on the DS and while there are some minor issues with looking back at old games, I still found it to be a fun experience. (Sometimes I wish I could just forget everything about the game and then start over from scratch, but oh I remember too much.) Square did such a great job on this game that it overshadows everything after it (Chrono Cross was terrible. The characters were bland, the plot way too complicated, and if it didn’t have Chrono in the title now one would have bought it) and Square refuses to make any sequels to it because fanboys would eat it alive unless it was perfect.

Is it nostalgia? yes! Because it was such a great experience that few games can match it. Most people don’t get nostalgic about a game that sucked (unless its one of those games that its so bad its classic. In which case it can be charming).

Story is a tool used to hide a weak game usually. A game should be a game… have gameplay and challenge the dexterity of a player.

My favourite example of this sort of thing is Enslaved. Loved the story so I played it to the end. Hated the game though, as it was so basic. That game really needed a “skip game” button so I could move on to the next cut-scene.

It’s interesting how story telling can be turned into video games. That video games can be turned into a story.

Most games are still simulators though. A few lovely, or perhaps not so, graphics away from being binary code. Whenever people talk about stories in games becoming more important I think they’re misreading games in general becoming more mainstream, there have always being games with solid stories, it’s only now they’ve started to gross billions of moneybucks.

Is cinema or literature really any different? There’s the triple A titles, then there’s everyone else in the mere mortal categories down below them. I’m not exactly condoning the way the system works but I am happy to pay for a product that can give me 30+ hours of entertainment and have no objection to those who created them making money from it… just a shame that the profit often isn’t going to the actual developers as much as it should. The real criminals are the likes of Zynga who have made untold stupid amounts of cash on the backs of half-arsed games that barely make shareware standards.

Gameplay should be about experience. It’s about safely being something you can never be for a few hours. It should be fun and it should leave you wanting more. I don’t much want to be in the “is it art?” argument because whether the game experience itself is art or not is irrelevant. Actually if cooking a damn soufflé can be considered art by some then I don’t see why not.

Games are a composite experience taking elements from writing, art and literature and using them to build the immersion. I’ve a couple of concept art books from Mass Effect and Bioshock on my bookshelf and the beauty and creativity is self evident within them. Is a game art? Maybe. Does a game contain art? Most certainly yes.

The trouble is games all follow similar narratives, and are heavily influenced by the latest films. Gaming need to get back to basics and improve on game mechanics, and forget trying to ape Hollywood.

The trouble with Hollywood is that films all follow similar narratives. There is always a love interest and a foreign bad man etc. Films might look great these days but how many actually say something new? Very few and usually only Indy films.

I would say games like Mass Effect have more complex stories than most films – if only because it requires about 40 hours investment rather than the limiting factor of 1.5-3 hours for film content.

I’d put TV series ahead of film in regards to depth of content also for the same reason.

Films are generally stale and unimaginative unless you are looking at Indy titles or psuedo-documentaries (that are still unimaginative but usually carry some moral weight) but that is another matter.

Games keep trying to replicate cinema for the same reason so much early cinema kept trying to replicate Theatre. It’s still a very young medium that is only starting to figure out its own language, so in lieu of any real ideas many game makers borrow the storytelling tools from games.

Not every game maker is Miyamoto, just like every early film-maker wasn’t Edwin Porter.

Great piece. It’s not only about interaction, but the fact that games are an action-focused media and there is only so much you can do with action.

I played Chrono Trigger for the first time two or three years ago. I often have trouble playing older games because I find it hard to get over their outdatedness, so I think the fact that I really enjoyed CT says something.

Despite being dated by the standards of representational and high definition graphics, the art direction and design sense in the game (courtesy of Akira Toriyama) remains one of the most timeless, unchanging appreciations I have for the game (the backgrounds, layered flat images providing the illusion of depth, in the opera house sequence, for example, still impress me with their stylization). The score may not employ the synthesized orchestral capabilities we have today, but still remains compositionally effective and emotionally engaging (that 600 A.D. map tune, and the dystopian bells of the post apocalyptic future still give me chills in all their technologically inferior glory).

The medium has matured because of a continuum created by tradition over time, but just like any other maturing creative medium worthy of analysis and scrutiny, its the assumed knowledge of those traditions and developed communicative conventions that form new directions for it (and subsequently make the old, from which the traditions sprang, feel antiquated). In American cinema this happened in the 70s, with the rise of the New American Cinema speaking to a generation, for the first time, inundated with previously digested filmic experience.

For me the best games are the ones with a high degree of emergent gameplay, such as XCOM, Civilization, GTA and Skyrim. Games that set up a world or a set of rules and allow non-scripted story-like elements to occur.

Who can forget that time I was escaping in a stolen ambulance, then hit a post and went flying through the windscreen into the sea? Or that time Zhang was bleeding out, so “Nuts” Vega dodged plasma bolts from several enemies in order to rescue him?

What I’m saying is, the emergent stories that happen only to you are generally far more memorable than the ones that the writers have scripted for you.

Yup – well said.

For me Fallout was even better than Skyrim for throwing up emergent stories. In Fallout 2 I my character met a strong silent type with a sniper rifle at a ruined motel. We shared our tragic back-stories. Even ended up dressing the same way (his hat made me better at shooting guns, we both looked good in tight boiler suits). We were never apart – companions in Bethesda games are just scripted that way. We slept in the same dinghy motel room, in a single double bed, before rising early to shoot varmits and get stuck on awkwardly positioned geometry together.

It was at this point I realised I was playing out a homo-erotic romance. It was not planned – I genuinely had a moment of realisation where as the player I twigged the character I was controlling did not share my own sexual orientation….!

This is a great article regarding the area of gaming. I am an animator and teach animation as well. The concept of Storytelling in animation is an important factor. We ask the question when developing a story, who is the character and what does he/she want? Then we have to determine the obstacles will keep the character from getting what they want. Think about Indiana Jones, he is the character; he wants the Holy Grail and the obstacles that will keep him from getting what he wants is the local natives and the Germans.

This concept from the movie is translated into the game as well. So, storytelling is a big factor in animation and gaming.

I really appreciated seeing Soul Reaver: Legacy of Cain and Silent Hill 2 in your article here! Playing them when I did, I took them for granted for the leaps and bounds in story telling and just how interactive they were for the time period of gaming they were released in. I have been thinking a lot recently about empathy and story telling in video games and games operating on high levels of interactivity with rich narratives seem to be key to evoking a empathetic response in players. This was definitely a refreshing read!

It can be a bit strange at times. I can play sports games like FIFA and Football Manager or strategy/simulations like Civilization for hours but couldn’t get into Skyrim for example because of the lack of story. In fact have enjoyed all the recent Bioware games even the ones criticised for being a bit weak (Dragon Age 2, Mass Effect 3) because the story was at least enjoyable.

I suppose I can to an extent ignore the story aspect for certain genres but once it comes to an RPG but even action and FPS games, a decent story becomes a must

Interesting that you mention Skyrim. My sons, 14 and 11, have played it for more than a year and enjoy the lack of a story because it allows them to create their own stories. Their characters have backstories, there are reasons for things happening and not happening, and there’s a strong narrative about where things are going only to be blown off course due to their decisions. For them, the game provides fragments of action and paths that they can assemble into a story that is theirs. Both boys dislike games that push a stronger story.

Video games often sacrifice overall excellence to highlight one or two features. Game play, graphics, or storytelling can differ wildly in quality. This was not the case though for Chrono Trigger, my favorite game of all time.

I don’t think that any game has ever hit the heights of immersion of playing Half Life for the first time when the soldiers actually took cover and tried to flank me…

Some people don’t really place value on plot in terms of an engaging story line being present in a video game, and it certainly boils down to everyone’s personal preference. Everything is subjective. It is, however, interesting to look at how the video game industry has developed, and how similar it is to the evolution of the film industry. Early film, while certainly pivotal to today’s standard of what constitutes a movie, was rudimentary at best back when people first started dabbling in movie making. Camera movement wasn’t really a thing, so you’d typically have a camera hoisted on a tripod, taking static film of a busy street, or a moving train (Lumiere Brothers, I’m looking at you). Obviously, over years of tech. development, camera quality, editing technique, and things like that, our standard for what constitutes a “good” movie has shifted. I think that’s for sure to be expected in the video game industry as well, given our grasp on new technology, and I think, like any other form of art, it’s going to face harsher criticism if the industry fails to deliver games up to par, especially if the game in question lacks the inclusion of an engaging plot (something that video game audiences more or less come to expect lately). If a game looks bad by today’s standards and the gameplay sucks, like any bad movie, that’s going to kill the overall immersive experience.

I like this post! It’s the kind of stuff I feel jealous for not writing it myself.

Games have the unique ability to tell a story by experience, this is ultimately where their art lies.

Even action-oriented games can ascend to the next level through good writing.

Chrono Trigger has one of the best storylines in the history of video games.

Bloodborne’s narrative is so deep and thought out. Even the DLC feels like it was planned from the early moments of game development. The fact that I felt like the plot was so sparse on first play through just shows that the more work you put in, the more you will get out of the story. A life lesson learned through figuring out plot.

Fantastic article. And very well researched!

excellent!

Nice work! I’m not a fan of video games, but I definitely appreciate a game that has a great story. (I’ve seen some examples with computer games, which are definitely quite a bit different). I also liked your analysis of how interactivity levels have changed. I think some people would argue that game interactivity has reached its peak, but I think if game creators focus more on story than the latest and greatest graphics, interface, etc., they can continue to create truly memorable games.

I always find it fascinating to look at how gameplay relates to story in games, and how the narrative is communicated. I LOVE how Shadow of the Colossus created that gamefeel for climbing/fighting the Colossi where you can start to feel something’s off about your mission before the twist at the end is revealed.

However, I’m always kind of on the fence about storytelling in games like Bioshock where the environment is FANTASTIC for the narrative but the actual gameplay doesn’t have a whole lot to do with it. The situations you’re fighting in are drenched with story, but the fighting itself is could be removed and you wouldn’t lose too much of the narrative. Now, the fighting is what makes it a game in many regards, so it’s an interesting challenge to figure out how a designer might bend gameplay expectations into something original which fits a wholly unique narrative.

When the plot thickens, we often get engaged, at the very least, in story-based games.

This seems quite comprehensive; it covers so many video games, that I don’t recognize about half of them.