The Text Adventure: Relic of Gaming History, or Timeless Medium?

Once upon a time, in a world without diverse colour palettes, without Sony’s Playstation or WASD controls, there existed the video game in what was essentially its most basic form: the text adventure. As the name suggests, the interface in these games consisted primarily of nothing more than words – the player would read to get an idea of their surroundings, then type simple commands to interact with the game world. Kind of like a technologically advanced Fighting Fantasy gamebook. As the field of games development became increasingly advanced, text adventures were produced less and less, creators beginning to favour platformers, fighting games, and – the truest successor to the text adventure – the point-and-click.

It wasn’t long before the text adventure faded into obscurity, then obsoleteness. After all, why read a chunk of text when you can see the dungeon in all it’s technicolour glory before you? Why go through the tedious process of typing ‘examine object’, when you can simply click the visual representation of said object? It’s hardly surprising the genre died out: to play a text adventure in today’s world of Skyrim and Portal would be like playing a dusty game of checkers in a room full of arcade machines… wouldn’t it?

Well… maybe not. In fact, to claim that text adventures are entirely dead and gone would be to ignore two very special things: the age of the internet, and the creativity inherent in the production of a text adventure. Whilst it’s true that this particular breed of video game has likely vanished from the face of commercial titles forever, it lives on – and in many cases thrives – in the form of free, browser-based games.

The question is, of course, why? Who continues to produce these seemingly defunct interactive stories? What appeal continues to be held within these fascinating time-wasters? And what lies ahead for a medium that is thought to have died long ago?

Reliving the Glory Days: Classic Adventures

With programs and plugins like Adobe Flash and Unity becoming standard issue for most browsers, and the popularity of emulators growing by the day, the internet is no stranger to the revival of classic gaming titles. In the 1980s, Super Mario Bros could only be played through purchase or bootleg (or perhaps a visit to a friend’s), whereas today, a quick google search will bring up thousands upon thousands of flash and emulator versions of the original title, ready to be played at the click of a button.

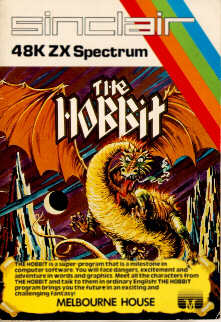

Text adventures aren’t excluded from this phenomenon – dozens of classic titles can be found online. As is the case with a surprising number of retro games, many offer something genuinely entertaining, and, ironically, seem new and fresh. One of the most notable titles that can be played online is the 1982 game The Hobbit, based, of course, on J.R.R Tolkien’s fantasy novel, restored through Java. You can play it here.

It’s safe to say it’s a faithful rendition of the original game. Indeed, some may say it’s a little too faithful, complete with excruciating ZX Spectrum loading times. The gameplay itself is often equally frustrating – Thorin consistently complains, the objective is incredibly unclear and death results in immediately being sent back to the beginning of the game. Perhaps this is just the effect of being a gamer of today exploring a creation of yesterday.

But there’s also an undeniable sense of fun (and, yes, adventure) in the game – unlike RPG successors to the text adventure, there’s a feeling of true choice in every action. The game doesn’t exclude the possibility that the player will not want to play by the rules, allowing for commands such as ‘attack Gandalf’ (although, inevitably, this never ends well). Sometimes it’s more like a text adventure Grand Theft Auto than a linear adventure game – the player can make Bilbo Baggins murder (or attempt to murder) key characters, drag around their corpses (if successful), and even become intoxicated on wood-elf wine (which alters the interface to a drunken slur in a stroke of comic genius). There is, obviously, a right way to do things – the game can hardly be beaten if the player has killed off characters that are vital to their success, and there are plenty of ways to die – but the programmers have included plenty of bizarre scenarios for the audience to have fun with.

What’s particularly interesting about this is that it couldn’t work in any other format – in a combination of Tolkien’s rich creations with the unique opportunities of player input, a text adventure is the perfect vessel. Because the text is so detailed in its description of events, a real-time, 3D game would pale in comparison. The text adventure establishes a unique dialogue between game and gamer, and in this case it’s a dialogue with a knowing wink – it spells nothing out, but when the player has come to understand its strange brilliance, there’s something fantastic about being in its company.

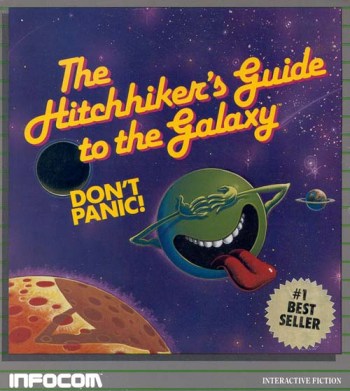

Intriguingly, another popular title from the 80s uploaded to the internet is also based on a British novel – the text adventure adaptation of Douglas Adams’ comedic science fiction masterwork The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy can be found here. Like The Hobbit, death comes quickly, unexpectedly and almost inevitably. Like The Hobbit, the interface makes little attempt to inform the player of how to avoid such deaths. And like The Hobbit, it’s tons of fun.

Unlike The Hobbit, however, the creator of the source material actually had a hand in the development of this. Seriously – in addition to the radio play and the series of books, Douglas Adams wrote the text adventure of The Hitchhiker’s Guide. To anyone who’s familiar with Adams’ style, this shouldn’t come as much of a surprise when playing the game. His trademark wit and slightly surreal sense of humour are present from the offset, and it’s his voice that makes the narrative feel warm and compelling (even, hilariously, in game over screens).

The game also differs from The Hobbit in that it isn’t quite as open – there’s no opportunity to assault your favourite characters here, and the world exploration is much more limited. What it lacks in this field, however, it more than compensates for in its employment of Adams’ writing. The prose is noticeably more sophisticated than the text in the aforementioned game, and the dry humour and vividly engaging descriptions lend the adventure a feeling of great authenticity (at the risk of sounding cliché, it’s as if you are actually in the novel). Even repeatedly dying rarely deters from the sense of fun, thanks to the game’s sharp handling of its interactions with the player. It’s worth a look, particularly for fans of the original books, with a smart, quirky edge that makes it a genuinely enjoyable experience.

So what can be taken away from this look at the original wave of text adventures? Well, for one thing, the significance of that word ‘adventure’. Providing players with vast, sweeping storylines and what could be seen as some of gaming’s first open-world environments, it’s no wonder they were popular. It’s also apparent that these kind of games did – and in many ways continue to – offer a completely different kind of experience. The presence of text and written narration is not simply a tedious part of a tutorial or cutscene, it comprises a core part of the game itself. This allows for a unique kind of relationship between player and game, one with all the intrigue and excitement of a large-scale RPG, yet also all the warmth and personality of a traditional written story. It seems that the text adventure was much more than a primitive predecessor to larger genres.

Something Old, Something New – A Slice of Life

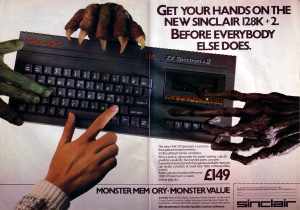

With this in mind, then, it’s no surprise that these games still live, albeit in a much less mainstream form. No more ZX Spectrums or Commodore 64s: all that’s needed to access the latest text adventures is an internet connection, a browser, and maybe a plugin or two. It’s even become common practice for enthusiasts to produce and publish their own text adventures on sharing sites such as TextAdventures.co.uk using free code engines like Quest.

So, what exactly has this phenomenon produced? What kind of games are now appearing in the new generation of text adventures?

In terms of genre, it seems very little has changed. According to the aforementioned site, the largest, most popular categories are fantasy and comedy – interesting when considering that The Hobbit and The Hitchhiker’s Guide fit perfectly into these respectively. However, it can also be seen that new areas have emerged, notably the ‘Slice of Life’ category, a strange phenomenon of a genre portraying everyday life. You could be forgiven for expecting this kind of game to be mundane in the extreme – how can an ordinary train journey or monotonous daily routine possibly provide an interesting backdrop for a work of fiction? Well, you’d be surprised.

Typical characteristics of ‘Slice of Life’ text adventures include a protagonist bound by societal constraints, usually relating to the life of the employee or a singularly mundane setting (a coffee shop or a park bench, for instance). This protagonist often possesses a cynical outlook on their dull existence, encapsulated once again by the use of text and narrative. Think Breaking Bad’s Walter White pre-criminal stage, or 1984′s Winston Smith, minus the terrifying totalitarian state and with a dosage of thin, pessimistic humour. The overall directions of the stories vary hugely – from an effective recreation of a normal day to a depiction of one in which everything falls apart, the seemingly limiting setting of reality is no boundary for the creativity of many text adventure developers.

A good place to start with this obscure breed of video game is Alex Warren’s Moquette, a strange little story about love, hangovers and the London Underground.

Told in the first person from the perspective of one Zoran Tharp, Moquette captures the monotony of the train journey coupled with the spontaneity of the human mind brilliantly, bringing an unexpected flair to something so seemingly colourless. Keep exploring and you may find extra appeal within the surprising visual tricks and plot twists, too.

Despite its repetitive and unremarkable nature, Tharp’s narration is rarely ever dull, his bitterness, wit and temper bringing life and humanity to the character. And there’s more to him than meets the eye – a lack of patience in stressful situations that can be both amusing and uncomfortably familiar, a wandering and lonely nature that makes his story both entertaining and soulful, and beneath it all, deep, conflicting desires. His internal monologue reveals a being like every one of us on some level, his predicament symptomatic of the human condition and the constant search for place and identity among a vast, seemingly alien collective.

You may leave this one feeling unsatisfied. Hell, you may not even want to finish it – it’s not for everyone, and it can certainly drag on at times – but if it is your thing, you may be in for a treat. It’s a strange, comedic, introspective look at ourselves and an examination of what we’ve become. In terms of an introduction to the ‘Slice of Life’ genre, there are few games more appropriate than this: for all its quirks and eccentricities, it’s arguably a fantastic representation not just of a man’s daily Underground journey, but also of the deeper concerns lying beneath the human psyche.

Another personal favourite is Sam Barlow’s Aisle, a game taking place – as the title suggests – entirely in a single part of a supermarket. It tells the tale of a man struggling with the past, the future, and a difficult decision involving pasta.

In an innovative stroke of creativity, the story is only ever a moment long. The interface is minimal, the player is only able to give one command per playthrough. This command, however, decides the outcome of events every time. Though this may seem restricting at first, it quickly becomes apparent that there are hundreds of potential commands, and therefore hundreds of different potential endings, thoughts, memories and plot twists that can occur. As the game itself puts it, each action decides ‘The end of a story. But not the only story…’ It’s difficult to go into detail here without spoiling the experience – but it’s a hell of an experience, delivering in nearly every area. It’s funny, it’s sad, it’s shocking, it’s one of the most unique, intriguing, and poignant works of art ever created, and it must be played to be believed.

‘Unmissable’ is a word thrown around a lot in most forms of media, but when it comes to browser games it’s somewhat less common. This, however, is exactly the term for Nicky Case’s Coming Out Simulator 2014.

Of all the ‘Slice of Life’ games mentioned here, this one best fits the category. As the title implies, it tells the true story of the creator’s experiences in coming out to strict, highly intolerant parents. You may expect such a plot to be dull, or just plain depressing – and yes, in many places it’s grim – but it’s handled with style, personality, and poignancy that makes it so much more. It’s innovative, using the device of a straight conversation between the player and the creator’s in-game incarnation to make the experience extremely personal. It’s striking, utilising simple artwork and visual style to evoke the strongest of emotions within the player. And above all else, it’s honest: despite labelling itself as ‘a half-true game about half-truths’, the scenarios explored are at once hugely relevant to Case himself and to thousands of others struggling with sexual identity, and it’s plain to see the passion he poured in to the project – a passion that can only come from experience. It’s a moving, memorable, and, yes, unmissable masterpiece. Words, ironically, cannot quite do it justice. Seriously. Play it.

A Quietly Thriving Medium

The games cited in this article are among the rarest gifts on the internet – funny, thoughtful, stirring and strange – and yet, the list is by no means exhaustive. There’s so much more out there – the hilarious ‘survival horror’ Don’t Shit Your Pants, the deceptively simple 9:05 with its blackly comic twist, and the excruciatingly awkward yet masterfully scripted The Writer Will Do Something, to name just a few of the thousands out there.

So what does all this mean?

Well, it defies the idea that the text adventure was only ever the foundation for larger, more complex games to be built upon. It demonstrates that in spite of the rise of consoles, the sheer scale of Grand Theft Auto V, and even the appearance of virtual reality with devices such as the Oculus Rift, there is still something to be said for a format that first appeared way back in the earliest decades of video gaming. The richness and simplicity of the written narrative, the uniquely intimate player interface, the depth, the humour, the sheer personality of the text adventure still holds power, still captivates players – albeit in a smaller, less commercial, more independent environment.

And this is something we often seem to overlook. The debate over whether video games can truly be considered art is ever ongoing, and will likely never actually stop. So maybe – just maybe – there’s even more to the text adventure. A legitimate and relevant form of video game? The examples cited in this article certainly seem to support the idea. But can a text adventure be considered more than that? Is it possible that these games fall distinctly into the category of art?

The answer, of course, is both yes and no. The reason for the complexity and divisiveness of the argument lies within the subjectivity of art – the perception of artistic value changes with every individual, and so the debate will never reach a definitive conclusion.

That doesn’t, however, mean that it’s pointless to talk about games as art – after all, the right kind of discussion can widen perspectives, constructively challenge what was once thought to be correct, change a single mind and the view of the world alike. We’re not going to find the meaning of life by talking about video games, of course (well, probably not), but the constant exchanging of views and ideas can only serve to help us reflect, therefore broadening our own minds and the minds of others.

Like the most popularly cited ‘art games’ of recent years such as The Last of Us and Braid, the listed games offer something nothing else can – powerful, well-told and satisfying stories, often over the course of no longer than half an hour. So whether or not they really are art (or even games – a point some members of the community may be adamant about), they certainly have the capacity to evoke strong emotion, from thrill, to joy, to poignant sadness.

Once upon a time, in a world without diverse colour palettes, without Sony’s Playstation or WASD controls, there existed the video game in what was essentially its most basic form: the text adventure. But it was more than that. And it still is.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

As a newbie sysadmin, I feel I’m living in a text adventure for some reason.

The one I remember playing a lot on my C64.. “You wake up. The room is spinning very gently round your head. Or at least it would be if you could see it which you can’t.”

Hitchhiker’s guide! The one I remember _not_ playing a lot because I never got anywhere. Finished Planetfall.

The truth is that games have changed considerably in the past 30 years. Sure, there were lousy games back then, just as there are now, but they were an entirely different kind of lousy. Usually they were, in my opinion, of the insanely difficult and un-fun type of lousy. There’s a lot less of those these days since insane levels of difficulty cause most gamers to do a 180 right quick.

Here in the UK there were a good number of such games published during the 8-bit micro boom of the early 1980s.

The first game to really start things going was Melbourne House’s The Hobbit which, on some platforms, included crude graphics for some of the locations. The parser for this game was quite complex, allowing the player to pass instructions on to other characters. The other characters in the game also had some form of artificial intelligence, granting them the ability to wader around at random and move things around. Consequentially no two games were ever the same.

Another significant developer was Level 9 who created huge games using text compression. These were sold for a huge range of platforms.

Another major development was when Gilsoft developed The Quill, a an adventure game construction kit. This allowed virtually anyone to create a game based around a standard runtime environment. Many games were then released to the market, some so cleverly constructed that major software publishers could pass them on at full price. Later add-ons were created that allowed in-game graphics, basic sound effects and other features. Text compression was eventually added, too.

Level 9 was great. The Snowball series was one of the most vivid/memorable games I’ve played — ever. I’m still trying to run away from those Nightingales. I used to order them direct from the UK for my Atari 8-bit, and they’d come in a DVD-type case, though they were on cassette.

I remember Level 9, they made some great games. I remember Knight Orc quite well. It came with a novella that filled in the background to the story.

I think the problem with text games was that you’d run into a dead end where the designer wanted you to do some particular thing, and if you didn’t do it, there was nothing else you could do. Adventure games need to give the player alternatives when he is frustrated. My kids play the Legend of Zelda games, and to my eye they have a lot in common with those early text games. The big difference is that when you get tired of figuring out the puzzle you are working on, you can set it aside and do something else.

If people continued to pour development money into text games, they’d probably be a lot more open ended and flexible than they were twenty five years ago.

Fantastic article.

I would say if there is one genre that really stood the test of time.

I am happy to see there are still many, many very creative people releasing this interactive fiction.

I really want to see some level of text based gaming come back. Hell it might be a great way to market a Wii Keyboard or something like that.

Haha, awesome. Yeah, Nintendo could be missing a trick. There’s certainly a lot more I feel could be done with it.

Thanks for the read and the comment!

Text gaming didn’t leave, it just went indie.

I remember great memories and genuine excitement about Adventure whenever a huge block of text would scroll into the screen, indicating a new area or a puzzle solved.

It’s a fantastic feeling, isn’t it? When done well, I find it can be a genuinely thrilling effect.

Thanks for reading and commenting!

I think that imagination plays a part in the appeal to text adventures. Also, great list of games. I will be sure to check some of them out.

Yeah, definitely. The details that can be conjured up with imagination are pretty much limitless, which certainly makes it a whole lot of fun.

Thanks for the read and the comment!

I just returned from BlizzCon 2015 and was my mind was blown! My son is one of the character artists for the World of Warcraft games for Blizzard, so I wanted to visit his “world” at the conference. The event was incredible and I left completely impressed with what is happening in the video game industry today. There were presentations on the storyboarding of games, the music, the cinematography, technology, actor voice overs, artistry, and so much more. So much goes into one game. I highly recommend to anyone that they try to attend it next year!

I think text adventures bring out the simplicity of games, but are compelling because it requires people to use their imagination. Imagination can sometimes be more vivid than 3D graphics.

Thanks for your comment!

Absolutely agree. ‘Simple yet effective’ really does apply in this case, I think. Good point about the vividness of the imagination – there certainly is that feeling of freedom and adventure that comes when playing a text adventure, and I really feel imagination is a huge part of that.

Great article. I started off thinking that this would never be entertaining to me but I started playing Zork (The Hobbit would not load) and I ended up spending an hour exploring. Your imagination just seems to take over once you get into the game a little bit.

Yeah, it’s amazing how immersive it can actually be, just through stimulating the imagination. It may be worth trying The Hobbit in a different browser – the site can be a little weird, sorry about that. Glad you found something else to enjoy! I haven’t yet played Zork; I’ll have to look into it sometime.

Thanks for reading and commenting, really glad you found it entertaining!

It was very intriguing to read about this topic seen through lens of a video game. One could also say that the text adventure falls into the subcategory of Interactive Fiction. As a writer, I find that the text adventure broadens the horizon for more exploration in a story (on the part of both the reader and the author). Overall, very interesting article. Nicely done!

Thank you!

Yeah, I was a little unsure of myself when describing it as simply a genre of video game, because, of course, it’s so much more. It’s a strange little category that lies kind of between game and prose, and I love it. Interactive fiction is probably the most accurate description, and like you say, the emphasis on story is often really charming.

I’m now in the latter half of my thirties and my girlfriend is in her mid-twenties and I was just rambling on about text adventure games. She looked at me like I had three heads and never heard of such a thing.

I distinctly remember a trip to a business with computers (and data stored on punch cards) when I was 10-ish and seeing the opening lines from Zork

A year or two later we bought a TRS-80 Colour Computer (with Extended Basic!) and I learnt to type by spending days and days and days with Pyramid 2000, Madness and the Minotaur, Raaka-Tu, Bedlam … and went on to enjoy those early “graphical” adventures like the Dallas Quest. I didn’t actually play Zork until much, much later.

It’s a shame these sort of interactive fictions passed away after the advent of the CD-ROM and Myst.

All this discussion and not a single mention of MUDs, MOOs or any online multiuser text based adventures! Does the fact that they’re running on a remote server and have multiple users somehow exclude them from being designated as text based game? I think not. If anything they’re far more imaginative and far longer player commitment than most single user adventures running on the local machine.

In that case, let me mention the Discworld MUD. A strange place where for over 15 years many, many people have been wandering around on the back of a giant turtle.

I really developed my interest in programming thanks to LPmud/MudOS programming. It was a great experience, with lots of feedback from other programmers and players.

Thank you! That was a major oversight in this article. Unbelievable. MUDs are still alive and well online, and I personally have a ton of great memories playing them. What better text adventure can there be than one you go on with your friends? I played MUDs for years and probably still would if not for the tremendous commitment it took to stay competitive with other players. MUDs made me a great typist, helped me develop an online identity, and immersed me in imaginative worlds that improved my descriptive talents as a writer.

I hope the author decides to update this article with a little research and expose on this greatly under appreciated gaming medium.

An oversight indeed – I’m surprised I’d never heard of MUDS until now. I intend to do some research/become involved, and hopefully add a section on the category to this article. Thanks for reading and commenting!

Interesting. You’ll have to forgive me for failing to include these – this is actually the first time I’ve heard of them. I’ll be sure to catch up on what I’ve missed as soon as possible! Thanks for letting me know.

I particularly remember one game where you had to use a vacuum cleaner to get rid of a ghost that was blocking a doorway… I was about 11 at the time, had never even heard of ghostbusters, and didn’t realise that people in the US called vacuum cleaners “vacuums” which, according to my dictionary, was something with no air in it. I eventually got past that particular hurdle by pausing the game (it was in basic), reading over the code (I was a nerd) in search of relevant keywords and guessing combinations involving everything I could pick up.

On reflection I suspect reverse engineering this game was more fun than the game itself…

I had similiar pain with a game called Hugo’s House of Horrors (not text based, but the same text input pain). In one of the rooms in the mansion, you open a cupboard to find a funny looking sprite on the ground. I must have tried a 100 different things to figure out what that sprite was. Eventually I looked in the game directory to see a file called “mask.gif”. Pick Up Mask. It was a wonderful thing when the click based adventure game (such as lucas arts games), was introduced.

Knowing the language is quite important when it comes to playing but most get by fine.

I would attribute some of my knowledge of the language (English is my second language, Norwegian my first) to my use of computers and especially text games. I’ve clocked close to 18000 hours on a particular mud (lensmoor.org 3500) and enjoy it just as much as I enjoy some graphic intensive games.

It is all about what you are looking for. Text lends itself to roleplaying games quite well as you can define anything without having to worry about how it will be done graphically.

Text-based gaming isn’t completely dead. There are niche markets, particularly with browser-based games.

I was a kid and I had a bare knowledge of English language as 2nd language, so it went like:

“You start off with your parachute snagged on a branch of a mangrove tree, leaving you helplessly dangling high above the jungle floor.”

> north

> go north

> down

> go down

> climb tree

> look tree

> look at tree

> look parachute

> objects

> inventory

> help

…

> untie parachute

In the immortal words of many MUDs that are still played today,

> What?

That looks like Espionage Island from Artic Computing. It was released initially for the ZX81, then ported to the larger memory ZX Spectrum with no changes – same limited text descriptions in upper case text, limited vocabulary, white text on a black background and so on. Their whole series of games were fairly limited plot-wise, and extremely linear – i.e. just one puzzle to solve at a time for most of the game. So if you got stuck on one puzzle there was no point exploring the rest of the game.

The only advantage that Artic’s games had is that they were quick, having been coded entirely in assembly language. Many other games of that era were written in BASIC, and therefore suffered from having slow parsers and logic engines, with some games taking almost a minute to respond to commands. One software publisher went half-way – they coded the vocabulary parser in assembly, but still had the logic in BASIC.

The literate gamer has not gone away. Yes there are fewer of them in proportion to mainstream gamers, but in reality the numbers are the same, or even greater. The market is out there for these games, someone just needs to take advantage of it.

Nostalgia overdose.

H2G2 was a game that you had to play with the hint book in your hand. There were a few places where you ended up in the dark and it would say something like ‘you can not see, hear, smell, taste or feel anything’. I have no idea how you were meant to work out that you were meant to keep looking until it changed to something like ‘you can not see, hear, smell, or feel anything’ at which point you had to ‘taste dark’ and then continue (or use some other sense, if that was the one that disappeared from the list of things you can’t do). Similarly, the Babel fish puzzle was crazy; you had to do so many things to get it that it seems crazy to expect people to work them out. You also had to make sure you remembered to feed the dog at the start, or you’d get near the end and be eaten by it.

I can’t help wondering if it was a primitive version of copy protection. Most people who pirated the game didn’t have access to the hint book, so they got stuck easily. Unfortunately, I played most of these games on my Psion Series 3 (not H2G2, because it was 150KB and I only had a 128KB flash card), and didn’t carry the hint book around with me.

They were willing to explore and exploit any environment and any popular genre. I miss those times.

Yes! Used to play some classics on my sun unix. Detective story, police procedural. Lovecraftian horror. Traditional, hard core Sci-Fi…

“Have you ever wanted to jump into a book and live inside that world? Here is your chance.”

This should stand as proof that graphics should not be in the forefront of the entire gaming industry, they had graphics then and did much better giving a fully descriptive story as was needed.

Back in the days, and I don’t speak from experience, computers were not for everyone so the market was different. Today, most gamers don’t have the patience to read a book, even less to think while doing so like you do in an interactive fiction game. Actually, the whole society is like that. So, shiny graphics ARE important today.

One major difference between the games then and the games now, is that there used to be a lot more of them that I actually had any interest in playing. Many of them I played clear through too, usually without an easily obtainable hint or cheat guide. Now, I’m waiting for the next halflife release and starcraft. And I’ve been waiting for a while. Beyond that, there’s really nothing I’m all that interested in. Of course, I’m older now too… less time for games.

Ah, fond memories of my first exposure to computers.

Where text adventures may lack the visual appeal of today’s hi-def environment, I will always think about the persistence of table-top RPGs in the realm of gaming. Unfortunately, text adventures lack the near-complete fluidity between the gamer and the game in platforms such as D&D or GURPS. Nevertheless, there will always be the loyal following and those interested in this slice of vast, concise video game history.

I really enjoyed your article. It gave me a glimpse into an era of gaming that I never really experienced.

I do tend to think that the argument about whether or not video games can be considered art addresses a foregone conclusion. I think most emerging mediums go through this same scrutiny before the argument simply loses steam, and then refocuses on a different emerging medium. At this point, video games are an established cultural medium, and only getting stronger as such – to briefly sing the praises of the argument’s effect – thanks to developers’ desire to make games that have artistic aims. For me, the conclusion of this argument is: of course video games can be art. I’d like to think that this is an obvious conclusion, but maybe this point of view comes with having grown up playing video games.

In any case, I look forward to playing some (hopefully all) of the text adventures mentioned in the article. Thanks for sharing!

One of my favorites, and one I’ve been playing for more than three years, is Kingdom of Loathing (kingdomofloathing.com). Yes, they do have images, but they’re stick figures, static GIFs, so it’s essentially text-based with a little accent. Humorous writing, complicated puzzles … all that stuff is alive and well in this fantasy RPG. They’re maybe halfway between pure text and an RPG like Bard’s Tale – more interface than the former, much more writing than the latter. Heck, they even have a grue familiar as an homage to some of the classic games. (It’s free to play, too. There’s a donation model, but non-donators don’t miss out on anything.)

I loved King’s Quest growing up! Pick up chicken. Pluck feather. Also it’s amazing that the Hitchhiker’s guide as a text based RPG and I’d love to get my hands on it. I think these will always have some spot in the world, because people like being “in” the story. It’s the same reason we have choose your own adventure books. It’s like reading a book, but choosing how it plays out.

I couldn’t get enough of the Sierra “Quest” games at the time. I was even trying to use what limited programming skill I had at the time to make my own. I LOVED those games and I kept playing them years after they were obsolete. I was also playing DOOM and DOOM 2 well into the current decade. I wouldn’t expect a younger gamer to want to play the older games, no more than I would want to play Pong.

IRBurnett,

Wow, but there’s a lot to think about here. I think that you’ve really uncovered some important points about a media form that doesn’t tend to get a lot of attention, in in historical assessments of communications technology. There were a LOT of things that I’d wanted to respond to, but here are the big points/questions:

I know you meant to call text adventures ‘time-wasters’ to engender discussion–and I guess that that just succeeded. Aside from all the other value you make evident in your article, videogames in general have long stood as a particularly nuanced example of the possibilities of interaction between audience and content. Even in the venue of text-based adventures, we are still constantly called on to read and think critically, to pay attention to detail, and to get creative in our solution-building, and all of it within an established structure whose rules [of the command line] we must come to understand, be able to function within, and perhaps even learn how to manipulate. That’s critical thinking, right there. And, in a more materially-, immediately-practically sense, it’s the opening of training in communications with non-human actors that, now, we do perform every time we say ‘Ok Google’.

You mention Hitchhiker’s Guide, which was my favorite text adventure; it was ‘brought back’ by the BBC a few years ago, but with the addition of graphics that provide an interpretation of the backgrounds described in the text and indicators of objects we can interact with (whose descriptions in the text we might have missed otherwise). How does this change affect our interaction with the game, especially given that, by its nature, no effects are actually necessary?

Also on H2G2: Aside from the eventual inclusion of graphics, the game originally had a cheat sheet walkthrough that could really help ease one’s frustration with navigation. This certainly sets it apart from modern visually-based games where glitchiness and other factors can impede one’s progress in ways that the structure of the presentation itself can’t necessarily help with. This also makes me skeptical of your claim that text adventures provided an ‘open world’, but, since you’re also addressing subjectivity, I’m not sure to what degree such a difference matters. They don’t need to be what we would today consider ‘open-world’ to have been expansive at the time, as we were still moving through that Hegelian universe of another’s imagination. That we might not have the opportunity to move in as many potential directions doesn’t lessen the plethora of possibilities we felt as we navigated these worlds, because we were still being presented with new and different options in a game world than we’d ever been able to enjoy before. The bits on-board the Heart of Gold were especially good for this.

The ‘slice-of-life’ modern examples you refer to indicate that the potential approaches that the game narrative might take in engaging its audience have expanded and inverted in the decades since text adventures first emerged. At that time, text [of length] was a far more predominant portion of our overall interactions with media, and, as stated earlier, the text adventures themselves took us out into realms of unknowability through their content. Now, though, the examples you use have aimed themselves more at our actual experiences as a base for engagement; this means that the strange, othered element in our interactions is, perhaps, more the text itself than anything. For a user that might have previously argued that the ‘textiness’ of text adventures was what put them off, might the novelty of the interaction today–with it’s lack of attention to specific, real, non-turn-based timing, specifically–be the big draw?

Finally, to the point of artfulness: Text adventures are of a format that, itself, in its entirety, could be subsumed into more modern virtual gaming worlds; we can enter a virtualized game world and watch an NPC sit at a computer and play a text-based game, and we can do so as part of a story, a narrative that, itself, can be considered art. The interactability of modern, virtualized game worlds, in the meantime, means that that act of engaging with text adventures in those settings could lead to the ‘materializability’ of the text in those narrative as something other than itself. The word isn’t the thing in our world, but it can be in the virutal one. Text adventures are of a kind, as well, that we can actually make them available to our own narrative, game-based creations. We can enter a virtualized game world and watch another real-life player sit at a virtualized computer and play a text-based game on a virtualized computer.

At the point that we’re passively watching someone else do it, whether that ‘person’ is real or not, it becomes meant for consumption of the moment by the consumer of the larger narrative. Again, story–presented however it’s presented–as art.

Oooh great read thank you!

This is a beautifully written and well organized piece that presents an incredibly strong argument. While reading this, I actually thought of an app that I downloaded to my phone called HOOKED. This app serves only to tell stories represented in the form of texts. What I appreciate about this app is the same thing I appreciate in text adventure stories; it allows the writers a greater freedom to use their own dialect. Mediums such as a novel or even a play couldn’t tell the story in quite the same way as games such as these.

Text based games seem to, today at least, exist in a limbo. We truly have been spoiled by hyperrealistic graphics along with the convenience and simplicity of of how we are accustomed to interacting with the digital worlds around us. I, personally, love the idea of text based games, but practically I have trouble getting into them. They’re clunky by today’s standards and although these games may be gold plated under just a layer of dust, that layer of dust may be harder to sweep away for some than for others. But whether you love them or you can’t stand them, text based games played an important part in video game history and are still looked upon fondly today. I believe it was the first Call of Duty: Black Ops that actually feature Zork in its entirety as a hidden Easter Egg for no reason other than respect and love for a beloved genre that’s fallen off the radar.

I must be getting old!

With age, I simply lost patience and reading too much from a computer screen is tiring. We were young. Now we are at best middle aged, at worst seniors. Most of us do not want or cannot waste as much time on tiring task.

I love text adventures so much, but at the same I can totally see how they are starting to wind down in popularity. People really want flashy visuals along with a well written story, but at the same time I think the rise of Twine games is a good sign they’re coming back

Neat! I’ve thought about crafting similar text stories with Twine. It reminds me of Depression Quest, which is a rather simple game to navigate, but the narrative evokes many emotions through text and music.

I think the love and appreciation for the games that are available at any given time surpasses mere acceptance.

I showed some Infocom games to some friends since I thought text adventures were a nice idea and when they saw there was no graphics they simply shrugged them off. Well, one did try Zork, and after a few minutes, he thanked me for showing him something he didn’t know.

Unfortunately, the dialog and descriptions were not always as good as we remember them.

One of the reasons that these games have enjoyed a resurgence is that the tools to create them are free to use and require very little experience to operate. Already mentioned in the comments, Twine is a perfect example of a simple to use platform that is actually quite sophisticated.

Text adventures are interesting because they foreground the limitations of the computer game and the logics that are used to create them. While most contemporary works are more visual, they can all be stripped down to the same structures that fabricate the text adventure.

One of the more frustrating qualities of games like Zork was in finding the command combination that was required to proceed. Although GTAV might conceal this limitation, even this “open world” is prohibitive of free action. This might be one of the reasons that computer games, like any fiction, are increasingly being studied in academia as forms or literature.

I have always wanted to play a text-based adventure game because I always thought of the idea as so intriguing that the world was basically defined on your creativity and own enginuity to play the game!

I was actually playing some of the games you mentioned on this article, and personally I loved “9:05”, and “Moquette” as well as “The Writer Will Do Something”. With “Aisle” I found your analysis was spot on and helped explain the perspective quite well regarding how open ended and yet chronological the story tends to be in that text game.

The same could be said of “Coming Out Simulator 2014”, which had a uniqueness for its humor, blunt approach and open ended gameplay, alongside the ending itself.

With that said, I do wonder if there has been any research done on the topic of text games versus visually presented games. Maybe someone should write an article about how the two may have occurred side by side and that somehow visually presented games can have as much of an impact as text games. It certainly seemed to be the casewith “The Writer Will Do Something” where the game revolved around such games and how the team tries to work together to make their product successful.

Its a thought really. With that said, a good article. It induced me to play text games once again. 🙂

Even if more options are available these days, and games are more accessible, I definitely think there’s still place for text adventures. Check out Stories Untold, a set of four interlinked horror stories that came out his year, that play with the format eof a text RPG, old bugbears intact and all. Really engaging, and provides a much freshers kind of spook than a lot of stale modern horror games.

Hopefully I’ll be writing on Stories Untold soon in fact.

I have died so man time playing The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, I have played it many times and am yet to finish it… but now I have the urge to try it again, thanks 😀

Great analysis! As many people have already commented, twine is an excellent modern-day source of text-only games. Overall, I think another thing related to a lack of text related games is that societies growth in digital media and immediacy has contributed to a lack of attention span. People simply aren’t patient enough to read something thoroughly and need immediate action/gratification to sustain immersion. The same phenomenon is seen with just basic reading.

I realize this is an old article, but I’m having no luck… when I was a kid, I used to play a text based game on cassette tape, on an apple 2e. It used two word verb+noun commands. What I remember of it is that there was a pool, and you had to empty the pool, climb inside, and retrieve ring. I think I also recall a fire in the house… anyone know what game this was?

Text adventure games seem to be making a resurgence. Since this article was written, Doki Doki Literature Club gained much notoriety and a bit of infamy. It was also used as a promotional game for the game that the company that made Doki Doki Literature Club wanted to sell. Having said this, DDLC was a well-made stand-alone game. If did help propel a sort of renaissance in this particular video game form.

I think one of the amazing things about the Hobbit (and the other Melbourne House title Sherlock Holmes) is that the game world progressed regardless of the player’s actions, I mean obviously the player could do things to disrupt or halt the progression, but people would go to work or visit certain locations or do specific things at specific times, which meant that different playthroughs could be very different, due to the time spent exploring a location (look at vase, examine painting etc) or just slow typing. A game which has somewhat recreated this in openworld 3d was Red Dead Redemption 2, where the NPCs will get up, go to work, go to the bar and do various other things during the day as has been documented by players who just spent the day staking them out. I’m going to check out some of the games you’ve written about, thank you for including links.

Peace,

Si

Good article.