Evolution of the Smart Heroine

In the last decades of the twentieth century and the beginning decades of the twenty-first, intellectual heroines have become more common across mediums. In fact, they’ve become a trope, with TV Tropes dedicating a page to The Smart Guy or in our case, The Smart Girl. TV Tropes describes this character as a person who is “prepared, sometimes Crazy-Prepared.” She is associated with “rapid-fire typing,” “techno babble,” and a deep and abiding love of books. Often, the smart heroine is also what TV Tropes calls a Meganekko, or a cute girl who wears glasses (often of the Coke bottle variety). The Smart Girl is often an introvert; she may in fact be what trope-lovers call a Shrinking Violet who gets bullied or pushed around frequently.

There is nothing wrong with a smart heroine who fits these tropes, per se. In her own way, this heroine type is a classic, like the oldest Disney princesses (Snow White, Cinderella, Aurora), whose main purposes were to sing, be achingly sweet, and wish for their princes to come. Like all heroines though, the smart heroine needed to evolve and has done it well. Not all smart heroines look the same anymore. Those who do embody classic tropes such as glasses, an introverted personality, and a tendency to talk high above their expected age level, also carry unique traits that make them multifaceted and relatable.

There is nothing wrong with a smart heroine who fits these tropes, per se. In her own way, this heroine type is a classic, like the oldest Disney princesses (Snow White, Cinderella, Aurora), whose main purposes were to sing, be achingly sweet, and wish for their princes to come. Like all heroines though, the smart heroine needed to evolve and has done it well. Not all smart heroines look the same anymore. Those who do embody classic tropes such as glasses, an introverted personality, and a tendency to talk high above their expected age level, also carry unique traits that make them multifaceted and relatable.

For the purpose of our discussion, we will define a smart heroine as any heroine in media whose intelligence is her major character trait. A heroine with this trait will also use her intelligence to further her story’s plot and make positive impacts on fellow characters. She may be classically smart in the ways we have covered, but she may also be gifted in other areas. For example, a smart heroine may not have a particularly large vocabulary or make perfect grades in school. She may not be interested in Science, Technology, Engineering, Art, and Math (STEAM) as we think of them today. However, she may be intelligent in interpersonal, intrapersonal, kinetic, nature-based, or other fields. She may use a combination of intelligences and other character traits to facilitate personal growth and the growth of others.

The Classical Bookworms

There are two profiles of classic bookworms. A “classic bookworm” heroine embodies the traits most commonly associated with a smart heroine. A classic bookworm like the ones listed below takes great joy in books, reading, and words. Reading is one of her chief pastimes, if not her number-one favorite. She spends more time reading or pursuing intellectual hobbies than interacting in “the real world,” and may or may not struggle socially. A classic bookworm is generally introverted. Her friendship circle, if one exists, is small and tight, although once she counts a real person as a friend, that person becomes an implicitly trusted confidant (e). Finally, the classic bookworm can have either an intellectual or fantastical outlook on life. If fantastical, her outlook will inspire her to entertain possibilities and solutions to problems that others don’t readily see. If intellectual, her outlook will turn more on the fulcrums of logic, deductive reasoning, or research.

Belle, Beauty and the Beast

Belle, or Beauty as she’s sometimes known, might be the oldest and most well-known smart heroine on our list. Most modern readers or viewers associate her with the Disney version, a girl immediately defined as a bookworm. In fact, that version of Belle is arguably the only literate resident of her “provincial” French village (Disney doesn’t specify a time period, but researchers place Belle in circa fourteenth-century France). However, Belle or Beauty is classically smart in almost every version of her tale. If she has siblings, she is painted as the only one with common sense. Her sisters are far more concerned with physical beauty and charm than, say, their merchant father’s safety on his travels, or helping ensure their household runs smoothly in his absence. If Beauty has brothers, as in an African version of the tale featured on HBO’s Happily Ever After cartoon series, they are lazy and not inclined to defend and protect their home or sister as they should. If Belle or Beauty is an only child, she is often painted as a retiring, introverted type who prefers the safety of her home and father to friends and society. In the Disney incarnation, Belle seems to want friendship but is far more comfortable with her beloved books than the people who constantly judge her as “beautiful, but [a] funny girl,” “rather odd,” and even “as crazy as [her father].”

Belle is also a classically smart heroine in an unexpected way. Many Disney analysts have said she’s a snob for calling her life “provincial” and not mixing with the other young women of her village. In internet conversations on this topic, you’ll even find a few people who claim the live-action Belle, who teaches village children to read, lords it over the other villagers. Belle is otherwise kind enough that these theories don’t hold much water. However, it could be argued that like any bookish heroine who is judged, she uses defense mechanisms. For instance, Belle reads while walking through town, and we can infer she does it every day. She doesn’t make eye contact. She might pat a little kid on the head or offer a “Bonjour,” but she only makes real conversation with the bookseller or, in the live-action version, her literate pastor. Once done at the bookseller’s, she heads straight home. She says she has to help her father, which is true, but these choices aren’t helping whatever unfriendly reputation Belle has garnered. Like a classically book smart heroine, she finds the literary world much friendlier and more accepting than the real one. Author Jennifer Donnelly explores this, and the ensuing fallout, in her novel Lost in a Book, a companion story to the live action Beauty and the Beast.

However, it is Belle’s weaknesses, her defense mechanisms, her longing for a different life, that help her evolve as a smart heroine. They’re what endear her to us more than twenty years after her most bookish incarnation came to the silver screen and the pages of companion stories. These weaknesses make her human, and they set her up to succeed, although at first, it looks as though she will fail spectacularly. Belle gets what she wished for–life in a castle and the accompanying fantasy world full of beautiful décor, enchanted objects, and realities beyond what her village has taught her exist. On the flip side though, she’s a privileged prisoner. In gaining what she wanted, Belle lost what she had–namely, the safety of her village and her close bond with her father. At first, it seems she got an unfair trade–a bitter, temperamental literal beast who is content to let her starve in a well-appointed palace room.

Belle mourns, as anyone would. In the musical version of her story, she sings the plaintive solo “Home,” wherein listeners can read regret for what she’s done. “Yes, I made the choice…but I don’t deserve to lose my freedom…” she sings. She goes on to muse that she, “never dreamed a home could be dark and cold…my heart’s far away,” and lament, “What I’d give to return to the life that I knew lately.” Yet with the gumption that has earned her admirers, Belle soon gets smart. She might be socially awkward and frightened of the Beast, but she’s intrapersonally intelligent. Intrapersonal intelligence is the art of knowing oneself well, and Belle knows herself. She knows her limits, and she knows what she will and won’t accept from herself, too. She has a deep sense of self-respect and faith that she can improve her world, and those show her in good stead. Belle acknowledges she’s made mistakes where the Beast is concerned–“He was mean and he was coarse and unrefined…but there’s something in him that I simply didn’t see.” She treats the castle denizens as friends, not servants, because she knows what it is to be judged by outward appearance. In the live action movie, we see Belle asking the Beast questions about his life, his experiences, and the castle, as well as sharing hers. These choices allow Belle’s character to grow. In addition, they let her take the inward knowledge she has built up, and apply it to an outside world that accepts her, a system that works for and with instead of against her.

Hermione Granger, The Harry Potter Series

When twenty-first century girls think of a smart heroine or see the phrase “smart girl,” Hermione Granger is probably one of the first that comes to mind. Arguably, Hermione I the most classic of the classically smart heroines we’ve discussed. This girl is not just a bookworm; J.K. Rowling calls her a “genius” and a “prodigy.” Some Hogwarts students might study a bit or do some summer reading before a new term. An excited first-year might page through her books, eager to learn. In contrast, by the time readers meet her, Hermione Granger has memorized large chunks of her textbooks, if not the entire texts. She’s been practicing spells for weeks or months and getting most of them right. She can answer any question a teacher throws at her, with textbook accuracy. Indeed, she’s eager enough–and brave enough–to practically stretch out of her seat with her hand raised for several minutes so Professor Snape will acknowledge her.

Also like a stereotypical, classically smart heroine, Hermione is what we’d call a “nerd.” She’s buried in a book even and especially outside of class, causing classmate Ron to note, “She needs to sort out her priorities” and call her “mental.” We don’t see Hermione engaging in any social activities until around book four, and even then, it’s mostly things like the Society for the Promotion of Elvish Welfare (SPEW), which most classmates think is a waste of time. Hermione is also classically unattractive, described as having buck teeth and “bushy” hair that usually remains untamed. In one of many scenes that have made him despised, Snape notes he sees “no difference” in Hermione’s appearance when a cruel classmate hexes her teeth so they grow almost past her chin. Hermione rushes out of Potions in tears. Other than Ron and Harry, no one else appears to support or sympathize with her.

In the case of the tooth hex, Hermione’s lack of support might be because most Hogwarts students are scared of crossing Snape or becoming his next target. However, in Hermione’s case, she has never done a lot to endear herself to the majority of her peers. She comes across as a know-it-all from the moment readers meet her, and unlike with Belle, it’s not a subtle defense mechanism. Hermione is quick to point out that less experienced classmates “[aren’t] very good” at their work, especially in first year when her peers are most vulnerable. She’s vocal about the fact that she considers books that weigh more than she does “a bit of light reading,” and makes remarks like, “Honestly, don’t you read?” Like a stereotypical smart girl, Hermione is also unable to deviate from the textbook, the rules, or whatever other parameters are placed in front of her to figure out problems or help those who need it, at least when we first meet her. One of her most famous lines, “I’m going to bed, before either of you come up with [an] idea to get us…expelled,” shows a form of maturity but also makes her look like a goody-two-shoes. First-time Potter readers might wonder if Hermione would snitch on or sell out friends, a la Percy Weasley, to get in good with authority figures. The two best friends she has, Ron and Harry, she gets in a somewhat cliched way. After Ron accurately observes Hermione doesn’t have any friends, she runs off crying to the girls’ room, a well-known move for middle school-age girls in books. It is only when the boys defend her against a troll that she becomes their true friends, a moment that gives Hermione humanity but may make her seem like a damsel in distress.

Yet Hermione redeems herself, and arguably grows more than any other classically smart heroine, giving the trope the most room to evolve with her. She doesn’t stay awkward and crying in the girls’ room for long. She learns where her best intelligences lie and how to make them work for her. Essayist Lorrie Kim explains that as a Muggle-born, Hermione struggles because she’s not used to the world of magic and its rules. She sometimes acts like a know-it-all because to her, magic has no logic and she’s afraid of failing, losing her place in a world that seemed to accept her. In fact, we find out in Prisoner of Azkaban that Hermione’s Boggart is Professor McGonagall, telling her she’s failed all her classes and thus “expelling” her from the Wizarding World and success in it. But when Hermione finds a place where logic works, she shines. The first time this happens, during the climax of Sorcerer’s Stone, Hermione is the one who saves the day not once, but twice. The first time, she calls on her logical intelligence and keen memory to remind Ron Devil’s Snare hates sunlight. She’s calm enough to warn him to relax, and to cast Lumos, which calls off the deadly plant. “Lucky Hermione pays attention in Herbology,” Harry says, acknowledging that logic and memory, not magic, mattered more in the moment.

The second time, Hermione gets her friends out of a dangerous situation when she solves a logic puzzle. The puzzle’s theme is Potions; Lorrie Kim posits that perhaps Snape crafted it with his logical, Muggle-born student in mind. Indeed, stereotypical magic–what Snape would call “wand waving and silly incantations”–doesn’t make a blip on Hermione’s radar here. Instead, she focuses on figuring out the potion patterns, getting their amounts correct, and watching her timing so she can unlock her part of the maze at the right moment. Hermione excels when presented with the scientific and mathematical exact art of potions, and the minute details contained therein. This is perhaps the first time we’ve seen a classically smart heroine engage in STEM and blow people’s socks off doing it, which gives the smart heroine trope even more room to grow. Belle and many other bookworms like her are usually more interested in literature than STEM, which gives Hermione a modern edge.

Hermione’s gifts for STEM and logical bent continue shining throughout the Harry Potter series. Hogwarts’ curriculum lines up well with STEM; Potions is comparable to chemistry, Herbology to biology, and Arithmancy to mathematics, to name only a few courses. But even if Hermione didn’t show interest in STEM or STEAM, her unique brand of “smart” would have served her well. Born to Muggle (non-magical) parents, Hermione has the least connection to the magical world of the series’ Golden Trio. Arguably though, Hermione’s Muggle upbringing makes it easier for her to think beyond boundaries. In Chamber of Secrets, for instance, the magical students and adults at Hogwarts are stumped about how to deal with the deadly basilisk. There aren’t any safe spells to help them dispatch it. Potions and plants can’t help eliminate the basilisk; they’re used to heal the damage it causes. Indeed, Hermione falls victim to that damage, becoming petrified and falling into the magical version of a coma. Before she succumbed, though, Harry and Ron find out Hermione united her magical knowledge with a Muggle talent–good, old-fashioned research. Once again, Hermione’s penchant for “knowing it all” marks her as a heroine, not an annoyance. Once again, her ability to look beyond magic, or find the logic within, helps her and her friends grow and change.

Hermione’s character arc turns on moments like these throughout the five remaining Harry Potter novels. Like Belle, she faces and conquers weaknesses, such as her almost pathological need to study everything at once, which nearly lands her in the Wizarding hospital for most of the year. She learns to break the rules, but only when doing so is morally right or otherwise appropriate, not for the sake of breaking them. Hermione’s friendship circle doesn’t expand much beyond Ron and Harry, but by the time the seventh book rolls around, she’s secure enough that she doesn’t need it to. Hermione has learned who she is, and the answer to that question is not defined by “Muggle” or “witch,” “logical” or “magical.” She has developed into a heroine who can be both, who can not only find peace with dual identities but own and enjoy them. In a world where readers, especially girls, are encouraged to define themselves primarily as one thing, Hermione breaks the mold. She teaches readers to be smart in any way that benefits them, to use all kinds of gifts in any combination, and to be the truest friend you can to the ones you have, whether that’s two or twenty-six.

Brilliant and Beating the Odds

Along with multifaceted identities, fully evolved smart heroines face many different obstacles inside and outside academia. Classic bookworms like Belle and Hermione face these, but their external and internal struggles are often kept separate. Belle becomes a prisoner, but in dealing with that, she must take focus off her desire to be accepted for who she is. Hermione Granger becomes a voice of a Wizarding World revolution and fights in a war, but while she uses her smarts to do that, she doesn’t have a lot of time for introspection or nurturing of her academic prowess.

The next step in crafting a fully evolved smart heroine, then, is to marry her external and internal stakes. Many modern smart heroines face tremendous odds, and situations in which they will fail emotionally, mentally, or socially if they fail academically. Our next group of smart heroines deals with situations like ongoing abuse, cultural problems, and inborn difficulties, not on top of their academic experiences but in direct conjunction with them. As they grow academically, these heroines are challenged to open themselves up to different types of learning. They are challenged to admit and deal with what they don’t know, and find solutions to their knowledge gaps for the sake of the people and world around them.

For the purpose of our discussion, a smart heroine who fits this category might be a classic bookworm. Alternatively, she might embody some classic bookworm traits and not others. The key to her status lies in her external circumstances. To be considered brilliant and beating the odds, the heroine in question must face greater stakes than social struggles, insecurity, or discrepancies between what is real and what could become real. She often faces real-world, external problems such as abuse, bullying, and cultural tensions. A heroine who is brilliant and beating the odds might also be pigeonholed as too little, too bookish, or too inexperienced to influence her circumstances for the better. She might live with the pressure of racial or cultural stereotypes, or the distinct possibility that her adverse circumstances won’t improve. Often, this type of heroine must combine book knowledge and “street smarts,” or real-world, “on the job” learning, to succeed.

Matilda Wormwood, Matilda

Roald Dahl’s Matilda is one of the most memorable smart heroines whose external stakes work in conjunction with her internal. She begins her story at a distinct disadvantage compared to the heroines we’ve discussed. At only about five (the film version puts her at six and a half), she is over five years younger than our youngest classic heroine Hermione. Living with parents and a ten-year-old brother, Matilda would be considered the low person on the totem pole in the most loving family. Unfortunately, she’s at an even bigger disadvantage because her family doesn’t love her. Dahl explains that Matilda “doubted her parents would have noticed had she crawled in the house with a broken leg.” From babyhood, Matilda’s accomplishments are ignored or shamed; when she writes her name in spinach at less than a year old, she’s only reprimanded for making a mess. Parental neglect forces her to walk ten blocks to the library alone, and when she brings home library books, her father destroys at least one of them.

In many cases, a smart heroine in Matilda’s situation would find refuge at school. That’s certainly the case for Hermione Granger, who felt misunderstood as a Muggle and found common magical ground at Hogwarts. But for Matilda Wormwood, school at Crunchem Hall is the proverbial “out of the frying pan, into the fire” situation. Headmistress Agatha Trunchbull has no use or respect for learning of any kind, nor does she like children. For her, being a headmistress is a power game, a sanctioned way to bully and intimidate. Every day, Matilda must face this woman, and the knowledge that because Trunchbull is the school’s highest authority, there isn’t much Matilda, a kindergarten/first grade student who has only attended formal school for a little while, can do. The kindness and mentorship of her teacher Miss Honey ensures Matilda can keep growing academically. It’s a miracle she progresses socially at all, but she does make several friends, probably based on the camaraderie of survival. However, it is only when Matilda opens herself up to different kinds of learning, and experiments with new knowledge, that she can face her adversaries and her hostile environments with confidence.

Neither Roald Dahl’s book nor the Danny DeVito/Robin Swicord film paint Matilda as a passive abuse victim. Because she is so young though, it takes her a while to absorb the idea that she can fight back. Genius or not, there aren’t many self-determined moves a preschooler or kindergartner can make–unless she applies academic knowledge to whatever real-world knowledge she has. For Matilda, this begins when she discovers her parents are fallible humans. The movie adds some interesting psychology to this. Matilda’s father, in a fit of rage, tells her that, “When a person is bad, they deserve to be punished.” The narrator then explains Matilda’s father “gave her the first practical advice she could use. He meant to say, ‘When a child is bad.’ Instead, he said, ‘When a person is bad,’ and thereby introduced the idea that children can punish their parents.” Matilda, like any small child, understands punishment and reward. She also understands, probably more than most kids, what personhood means. Dad is a person, with the potential to be bad. Bad people are punished. Dad has been bad, and ergo, should be punished. This inspires Matilda to engineer some fairly harmless, but memorable pranks, such as mixing Mom’s hair dye into Dad’s shampoo and gluing his hat to his head. They lead to needed comic relief, but Matilda’s not laughing–much. Unbeknownst to her, she’s practicing for a bigger, scarier enemy.

From her first moments at Crunchem Hall, Matilda impresses her classmates and Miss Honey. With true modesty and matter-of-factness, she multiples double and triple digits in her head, and shares that she has already made significant inroads in the Western literary canon. However, this knowledge isn’t enough to make school bearable. Miss Honey tries to get Matilda transferred to a more advanced class to ensure proper stimulation, but Trunchbull won’t have it. Once Miss Honey singles Matilda out for good, the Trunchbull appears to single her out for ill. (In the film, her motivation is also tied to a meeting with Matilda’s father, in which he makes his daughter out to be a brat). At first, Matilda is content to keep her head down and stay quiet, like the rest of the student body. Yet she quickly realizes she has a lot to learn about coping with someone who’s not only an abuser, but a tyrant. She can’t hide behind books like she can at home, and harmless pranks won’t dent the Trunchbull’s sadism. But open rebellion will only get Matilda punished. It’s not stated outright, but rebellion might get her removed from school, or make her too afraid to go–something Matilda couldn’t cope with. She’ll have to combine book smarts with street smarts to win this battle–although here, the “mean streets” are the normally innocuous halls of elementary school.

Fortunately, Matilda is well-equipped to handle this challenge. Her very name comes from two High German words meaning “strength” and “battle.” After seeing schoolmates like Bruce and Lavender terrorized, and spending a little time in the Chokey herself, Matilda is more than ready to go to war. The situation reaches a breaking point when Trunchbull takes over Miss Honey’s class and has a violent reaction to a prank–a newt in her water glass. She blames Matilda, who stays quiet, but not cowed. Instead, Matilda is able to coach the glass to tip over, from her desk across the room. After several minutes of mental coaching, Matilda feels as though “tiny hands were shooting out of her eyes,” along with her eyes burning. The glass tips and shatters, alerting Matilda to her developing telekinetic powers.

It doesn’t take our heroine long to realize she can use these powers to help others and, in turn, save her school. Learning Miss Honey’s dark secret–the young teacher is Trunchbull’s beleaguered niece–adds an upshot to Matilda’s motivation. Once again, she combines book smarts with a good dose of courage and recklessness, teaching herself how to control her powers based on her limited knowledge of how and when they work. The film adds a psychological component, wherein Matilda draws on memories of her parents’ verbal abuse to make objects do exactly what she wants. Once she has her powers down, she slips out at night to sit on Trunchbull’s garage roof and use them, making Trunchbull think her house is haunted. Trunchbull is properly horrified, screaming “Leave me alone” and throwing objects around, but gradually becoming too traumatized to act–as she has left many a student before.

Matilda’s powers hold her in good stead during the climactic scenes of her book and film. When Trunchbull takes over Honey’s class again, Matilda manipulates the chalk and other classroom objects to make the headmistress think the ghost of Magnus Honey has come to avenge his abused daughter. The scheme succeeds, but this isn’t Matilda’s coup de grace in beating the odds. That happens when she subverts her parents’ attempts to spirit her away to Guam ahead of the authorities, who have exposed Mr. Wormwood’s criminal extortion. Matilda, visiting Miss Honey at the time, is armed with adoption papers, and we’re to assume she’s been carrying them around for a long time. She confirms she got them from a library book. “I’ve had ’em since I was big enough to Xerox,” she explains, hinting that she has understood for years her parents are not good custodians of her, nor are they her only option. The neglectful Wormwoods don’t care, so long as Miss Honey doesn’t call on them for child support, and both heroines get the loving family they’ve always needed to thrive. Thus, Matilda has beaten her own odds and helped Miss Honey beat hers in the bargain. Matilda has learned her academic prowess can help people in the real world, and even win personal battles everyone thought she was too young, too small, or too naive to face.

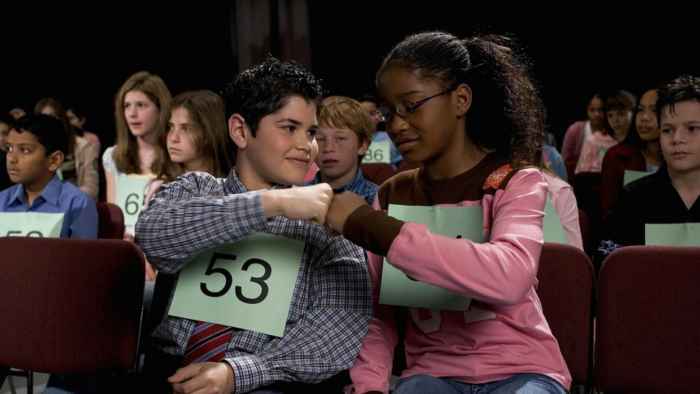

Akeelah Anderson, Akeelah and the Bee

Even smart heroines raised in loving families can face tremendous odds, as Akeelah Anderson shows us. Akeelah, heroine of the 2006 film Akeelah and the Bee, is an African-American eleven-year-old growing up in a rough Los Angeles neighborhood. Her father was shot in a random act of violence when she was six, so Akeelah’s only parent is her hardworking single mother, who does not appear to support Akeelah’s dreams. One of Akeelah’s brothers is in the military and usually not around. The other is on the precipice of gang activity, and Akeelah’s older sister is a teen mom. Akeelah herself is exceptionally bright, especially in the fields of spelling and language arts. But her school, Crenshaw Middle, is substandard in curriculum and construction. “Why would I want to do anything for a school where they can’t even put doors on the toilet stalls?” Akeelah asks her principal when he suggests she represent Crenshaw in a school-wide spelling bee. When the principal presses her, Akeelah explains she “ain’t down for no spelling bee” because “everybody [will] call me a freak and a brainiac.”

It’s clear Akeelah, though bright, doesn’t see much of a future for herself, at least as long as she stays in her neighborhood and school. Watching a tape of the previous year’s National Spelling Bee only cements this. Most of the contestants are white or Asian, and Akeelah doesn’t recognize any of the words being called. Intimidation flashes across her face when she hears contestants asking for “language of origin,” and being told, “Latin” or “Greek” or “French.” “I thought this was supposed to be English,” Akeelah mutters. Her family is no help. Mom disapproves of the whole idea; she thinks Akeelah should concentrate on summer school, where she’s been sent to make up for skipping classes during the year. Her brother predicts, “You’re going up against a bunch of rich white kids. They’re gonna tear your black [butt] up.” This feels Akeelah with personal and cultural shame, as it drives home the idea that blacks are oppressed, lesser, and not as smart. Even when Akeelah gains a mentor in Dr. Joshua Larabee, she faces shame and internalized categorism. Dr. Larabee censors Akeelah’s natural speech cadences, calling them “ghetto” and saying, “We only use words from the dictionary in here.” Akeelah feels personally attacked and minimized, as well she should. It doesn’t help that Dr. Larabee is black; if anything, this sends Akeelah the message that people of her own race only think themselves worthy to the extent that they can mimic whites and white culture.

Like Matilda, Hermione, and others before her, Akeelah proves you can’t keep a smart girl down for long. She tackles Dr. Larabee’s “ghetto speech” comment head-on, letting him know, “I don’t need help from a dictatorial, supercillious gardener.” She balks at Larabee’s rigorous spelling bee prep regimen, but soon finds comfort and stability in learning and memorizing words, stems, and origins. Akeelah proves herself a tireless, if sometimes smart-mouthed, student, and gradually opens up to Larabee about her insecurities. This gives Akeelah a level of uniqueness, and an edge over the other smart heroines we’ve discussed, whose stories don’t center on mentor-mentee relationships. In addition, working with Larabee prepares Akeelah to accept not only who she is academically, but who she is culturally and where she lives and grows as part of that culture.

Throughout the spelling bees leading up to the National Bee, Akeelah is constantly reminded that a “little black girl” isn’t expected to win, and might be considered a traitor to her neighborhood and culture if she did well. Akeelah has to lie to her mother to attend spelling bee practice at Woodland Hills, an upscale school for highly gifted kids. Some students she meets, like Javier Mendez, are friendly. Others, notably Dylan Chu, greet her with suspicion and derision. “It starts with an X,” Dylan spouts at Akeelah when she starts to spell “xanthosis” with a Z. Some of the parents too, don’t think Akeelah belongs, because she’s black and because she’s female. Dylan Chu’s dad is fairly vocal about this, out of fear that Akeelah will relegate his son to second place not only in spelling, but for “[his] whole life.” Worse, Akeelah’s mom is furious when her daughter’s lie is exposed. Akeelah has to promise to double up on chores for three months to even continue competing, and at one point, she only advances because a cheating contestant is caught. Akeelah’s neighborhood eventually respects her prowess in spelling, but they put intense pressure on her to win against 199 other contestants, most of whom have been training longer, harder, and with better resources. She’s treated with what TV Tropes calls a You Are A Credit to Your Race attitude, and breaks down at one point because of it.

At times though, it takes a breakdown for a heroine to come back stronger. Akeelah is a notable smart heroine in that she is the first one in our discussion to truly exemplify this. Heroines like Belle and Hermione have certainly cried or raged before, but Akeelah gives full vent to her problems, not just her feelings. By the time the pressure gets to her, Dr. Larabee has refused to coach her further, and her best friend Georgia has branded her a lousy friend. “Dr. Larabee don’t wanna coach me no more. Georgia don’t wanna hang out with me, and all these people are expecting me to win…it’s too hard, Mama,” she sobs to her mother one night. This serves as a wake-up call for Mom, who shares her own insecurities with her daughter, explaining she was afraid Akeelah would be one loser among hundreds at the bee, and thus, give up on her dreams like Mom gave up on medical school. Mom lets Akeelah know she is valued and a source of pride because of who she is, not how well she can spell, but that spelling is also a valuable gift she should nurture. She also challenges Akeelah to think about the “50,000 coaches” she has right in her neighborhood–the same people who, though they may have pressured her, truly have her best interests at heart.

Akeelah is able to take Mom’s advice and bounce back. Although Dr. Larabee agrees to coach her again, we see a montage of Akeelah working with other coaches across cultures, from her African-American teacher to a local Asian store owner to a multicultural mix of schoolmates. She’s floored when one of her older brother’s friends tells him to blow off gang activity to “stay here and help your sis”–which he does. During this time, Akeelah memorizes 5,000 tough spelling words, including championship-level ones. More importantly, she sees that people from an impoverished neighborhood can and do support education and big dreams, without expecting her to mimic white people or accusing her of betraying her roots. She calls her neighborhood “[the place] where I learned how to spell,” and viewers are meant to know she’s not just talking about definitions, word origins, and spelling. She’s talking about embracing roots, breaking down barriers and stereotypes, and accepting her gifts as gifts, not stumbling blocks that make her different or freakish. Akeelah does win the National Bee, becoming a co-champion with Dylan, who she wins over as a friend. Viewers cheer for that, because an academic victory is what this heroine needed to complete her journey. Yet they cheer even more when Akeelah says “my neighborhood, where I come from” with a sense of pride. She might still have to go to Crenshaw, where they can’t put doors on the toilets. She might always deal with bullies and only have a couple true friends, and her family might always struggle with some of the issues that plague people of their socioeconomic standing. But the lessons Akeelah has taken from the National Spelling Bee, and what it took to get there, mean she will be more than okay. She will become “brilliant, gorgeous, talented, [and] fabulous.”

Strange Outside, Scholarly Inside

Does a smart heroine always have to look and act smart from the outset of her story? Does she always need a deep connection to books and academia to be considered brilliant? Can she use her smarts to beat the odds even if she doesn’t get straight A’s, win academic competitions, or use her brains to save people? The answer to all these questions is “yes,” and some of our most recent smart heroines prove it. As the smart heroine has evolved, she has not only increased her external stakes, but given her personhood a makeover. The last smart heroines in our discussion don’t always look or act the part, but that endears them to readers and viewers. We root for these heroines not because they fit the mold like Belle or Hermione, and not because they battle with their brains like Matilda or Akeelah. These smart heroines, we love because they broke the mold in half, and yet stay true to what it means to be smart heroines in their own ways.

Keep in mind, a heroine who is strange outside and scholarly inside is not mentally ill, emotionally unhinged, or without social skills. When applied to this type of smart heroine, the word “strange” refers to the fact that she doesn’t look or act smart on the outside. This type of heroine might read and enjoy certain books, but she won’t devour them. She won’t use book smarts or street smarts to fight against external circumstances, at least not in obvious ways. She can have a bevy of friends or only a few, and will likely enjoy pursuits that aren’t traditionally intellectual. The heroine who is strange outside, scholarly inside might even look quirky or flighty to a classic smart heroine. Yet, this heroine consistently proves herself intelligent in outside-the-box ways, endearing herself to broad audiences inside and outside her universe.

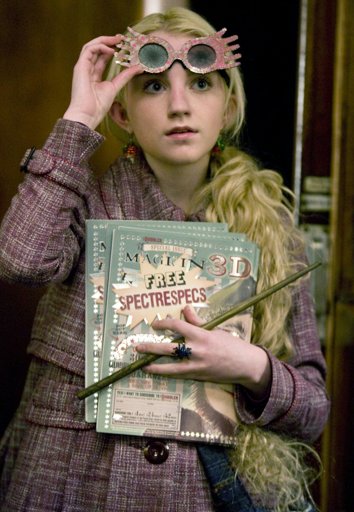

Luna Lovegood, The Harry Potter Series

Put “smart heroine” or “smart character” in the same sentence with Harry Potter, and most people will fill in “Hermione Granger.” As we’ve discussed, Hermione is a genius and a strong heroine. Many girls who read the Harry Potter books or watch the movies identify with her, including her portrayer Emma Watson. However, Luna Lovegood is not to be forgotten. She’s a Ravenclaw, but doesn’t fit the stereotype of the wise and learned Hogwarts student. Most students claim she’s “odd,” and the majority, Hermione included, tend to call her “Looney Lovegood.” Indeed, Luna embraces beliefs that even her fellow wizards and witches find strange. She’s an avid reader of the alternative press paper The Quibbler, of which her dad is the editor. She’s one of the only Hogwarts students who can see and interact with Thestrals, skeletal black horselike creatures that pull carriages. Luna often talks about creatures like Nargles or Wrackspurts, and blames them when people lose objects or have a bit of “brain fog.” As noted, she’s almost universally ridiculed for this, even among fellow Ravenclaws. We don’t know anything about Luna’s grades, and she certainly doesn’t seem the type to memorize textbooks and research for fun, like Hermione. She’s whimsical, almost ethereal, and seems absentminded or spacey. Coming across her in the Muggle world might be like coming across a classmate who makes great connections in Advanced Placement English or Chemistry, yet still wholeheartedly believes in Santa Claus or has an imaginary friend. So then, what sets Luna apart as a smart heroine? Beneath the odd packaging, what makes her so brilliant?

The key lies not in the fact that Luna makes great grades or is a bookworm, but in the type of thinker she is. At first blush, readers and viewers may wonder how this girl made it into Ravenclaw House, because Ravenclaw is the house of the “ready mind, where those of wit and learning will always find their kind.” It makes more sense, though, if readers focus on the word wit. “Wit” connotes not just a scholarly bent, but creativity, the ability to take the knowledge you have outside the box. If there was ever an outside-the-box thinker, Luna Lovegood fits the bill. She thinks beyond the obvious, textbook answer and accepts there is more than one way to get things done. In one of her interactions with Harry, she tells him, “My mum always said the things we lose…come back to us eventually, if not always in the way we expect.” At the time, she and Harry are standing in a corridor, where a bully has somehow hung Luna’s sneakers from the ceiling. Certainly, the bully didn’t give the sneakers back, and Luna was either unable or unwilling to summon them back to her closet–but they did come back to her. With this seemingly insignificant incident, Luna teaches Harry to look past what’s right in front of him, a skill both students will need for their coming travails.

Luna Lovegood is so popular with some readers that they wonder why she doesn’t show up until book five, well into the series. However, there could be a solid reason for J.K. Rowling’s choice not to bring Luna forward until Order of the Phoenix. Recall during this book, Hogwarts nearly cracks under the strain of Delores Umbridge’s rule. In direct contrast to Luna, Umbridge thinks only inside the box–and she shoves people into the box with her. She disdains practical learning and stays willfully blind to the reality of Voldemort’s return, not caring such blindness could get her students killed. Worse, she punishes and quashes anyone who dares go against her. What a terrible adversary for a heroine like Luna–and yet, what a perfect one for her to win against. In many ways, Luna is Umbridge’s foil. They don’t go toe to toe; readers and viewers don’t see Umbridge singling Luna out or even punishing her, although we can assume it happened because Umbridge is an equal opportunity abuser. However, Luna’s presence reminds her fellow students there is hope and light still in their school. There is something greater worth fighting for, even if they can’t see or touch it, or it seems strange to them. Perhaps to show this, J.K. Rowling makes Luna one of the biggest supporters and first recruits of Dumbledore’s Army. In a beautiful scene of the Order of the Phoenix film, we see Luna is one of the first DA recruits to cast a Patronus–a hare. The animal sums up Luna’s personality nicely. It’s a bit shy and somewhat hard to catch hold of, and because of associations with works like Alice in Wonderland, it could be considered odd. The hare is smart, though in a more understated way than a fox or eagle or owl. Most important, like Luna, hares and rabbits can be associated with new life and joy, something Luna brings plenty of to Hogwarts and Harry’s friend group.

Finally, Luna Lovegood is brilliant because of how she interacts with people. She’s empathetic, though not always obviously so. Luna’s empathy doesn’t come from living her friends’ situations and relating to them. If anything, she’s far removed from the typical teenage lifestyle and associated feelings. That’s why she is thrilled when Harry asks her to go to a Slug Club party as friends in Half-Blood Prince, and why she says being in the DA “was like having friends.” Yet Luna remains empathetic because she can observe people and make them aware of feelings, ideas, or gifts they weren’t aware they had. Like Hermione, she makes her friends think in new ways, but without the intimidating “I’ve memorized my textbooks” factor.

Luna first shows this skill while talking with Harry about Lord Voldemort and his strategy. Just before this, she has explained only people who have seen death can see thestrals, thus explaining why she and Harry can see them (Harry lost both parents, while Luna lost her mother). A stressed-out Harry asks Luna what she thinks Voldemort wants, and how he can anticipate his enemy’s next move. “Well, if I were You-Know-Who,” Luna says, “I’d want you to feel all alone, cut off from everyone else.” On the surface, it’s a simple answer, exactly what Voldemort would want. Deep down, Harry knew it, too. It was the internal, hidden reason he formed Dumbledore’s Army and stuck so close with the students of that group during Order of the Phoenix. Until Luna put it in words though, Harry wasn’t able to access that information. He wasn’t able to face up to that knowledge, because doing so might have rendered him emotionally helpless. Luna’s delivery is soft, matter-of-fact, and again, empathetic. She tells Harry the truth, but in a way that boosts his confidence and reminds him at the end of the day, he is more than The Boy Who Lived. He is a valuable person, worthy of life because everyone is worthy of life. He must save the magical world not for his own sake, not because Dumbledore demands it, but because in doing so, he will save goodness and hope from those who wish to destroy it. Of course, Hermione could’ve told Harry the same thing, and used statistical data to back it up, but Luna’s brilliance and light are what Harry and the Wizarding World needs now. Defeating an enemy who wants to cram everyone into his pureblood fanatic mold requires the acumen of someone who got an Outstanding in creativity, wit, and learning out in the field.

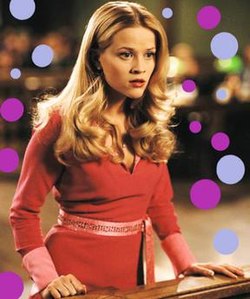

Elle Woods, Legally Blonde

If ever a smart heroine existed who didn’t look or act the part at first, it would be Elle Woods. If anything, Elle seems the exact opposite of a smart heroine at first. She’s a fashion major at the fictional CULA, president and sweetheart of her sorority Delta Nu, and a social butterfly with a handsome, popular boyfriend. At face value, Elle looks like the kind of girl who’d bully a smart heroine, or at least disdain her. Yet Elle endears herself to viewers because she’s surprisingly, sincerely sweet. She has a tight group of sorority friends, but over time proves she’s no respecter of persons. Like Luna Lovegood, Elle is highly empathetic and interpersonally intelligent, but this is not enough to keep her in good stead on her character journey. Elle’s arc, and what makes her smart and unique, comes from what she learns about new fields, and herself, during her story.

Because Elle’s innate smarts are interpersonal, the people in her life are vital to her. One such person is boyfriend Warner Huntington III, who she expects will become her fiancé early in the movie. When Warner dumps her, Elle is devastated, but less because of the act of dumping than his flimsy reasons why. Warner is going into law school at Harvard, and claims he needs “someone serious” as a girlfriend. “I need a Jackie, not a Marilyn,” he clarifies. A stunned Elle counters, “So you’re breaking up with me because I’m too…blonde?” It’s meant as a joke, but viewers know there’s a lot more to it. Warner is in fact discarding Elle because he thinks she fits the “blonde” stereotype–flighty, no intellectual prowess, and little interest in anything other than looks, clothing, and fashion. Even Elle’s parents buy into this somewhat, claiming she’s not serious. Her dad says the kind of girl Warner wants is “dull, boring, and serious–and you, Button, are none of those things.” He means it as a reassuring compliment, but Dad reinforces the idea that Elle is not good enough for the people around her. Thus, Elle subconsciously decides she can only reclaim her worth if she gets Warner back. She heads for Harvard with a car full of pink possessions, a borderline LSAT score of 179, and no idea what she’s in for–or the good things waiting for her.

At first, it seems Elle’s Harvard experience will be more of the same. Male students taunt her with comments like, “Hey, check out Malibu Barbie” and “Where’s the beach?” On her first day, Elle gets kicked out of class for not doing an assignment we don’t know if she was aware of. She’s woefully underprepared for the competitive nature of law school; she doesn’t have basic necessary tools, like a laptop, and answers questions incorrectly or simplistically. As for Elle’s social personality, it’s fairly useless at Harvard. Elle introduces herself to classmates as a “Gemini vegetarian” and Delta Nu sister, while her contemporaries define themselves by prestigious academic awards and humanitarian efforts. When she does get invited to a party, it’s a cruel trick courtesy of Warner’s new fiancée Vivian. A snooty classmate keeps Elle out of a study group, snarking, “Maybe there’s like, a sorority you could like, join instead, like.” All signs indicate Elle will end up crashing, burning, and looking incompetent.

The worse things get for Elle though, the more determined she becomes to prove herself. Fairly quickly, her focus shifts from getting Warner back to proving herself as a competent law student. What’s great about that though, is Elle adjusts to law school on her own terms, without losing her personal style. Her laptop skin is embroidered in hot pink, and whenever we see her studying, she’s also doing something like getting her hair done. While her fellow students wear khakis, cardigans, and collared shirts to class, Elle sticks to her signature hot pinks, deep reds, turquoise blues with sparkles, and florals. This might not be “smart” in the traditional sense, but it’s a highly intelligent move on Elle’s part. It shows she is resilient, able to rise above stereotypes and cutting remarks thrown at her. Moreover, Elle’s attitude demonstrates that although people don’t take her seriously, they should. She might not have the traditional law school credentials, but she’s willing to learn what she doesn’t know and put it to good use. Her efforts pay off when she does well at Harvard–so well that she nets a coveted internship and a place on a high-profile murder case.

Elle’s knowledge of the law doesn’t come to the forefront during her internship, leading some viewers to assume she hasn’t become that smart. However, it is when Elle is allowed to use her innate intelligences, to be herself, that she triumphs. Her interpersonal gifts make the somewhat hostile environment of Professor Callaghan’s firm more bearable. For instance, she gives adversary Vivian another chance–they bond over Elle’s dog Bruiser–and finds out the other girl is a powerful ally in a male-dominated office. Elsewhere, Elle uses her knowledge of fashion to expose a lying witness, who claims to have been defendant Brooke Wyndham’s lover, but is homosexual with a presumable long-term partner. She puts her reputation and place at Harvard on the line to help a beleaguered divorcee who unfairly lost her beloved dog in the settlement. Elle also clings to her faith in Brooke’s innocence despite everyone else’s skepticism, based on the fact that she knows Brooke personally and considers her a friend. Elle might not rattle off laws, statistics, and precedents as readily as someone like Vivian, but her intelligence has taught her the law is about people. It’s about getting to the root of who the clients are and helping them keep their good names. As an intensely loyal friend and expert at reading people, Elle Woods is the perfect candidate to defend Brooke Wyndham, another woman who is judged only by face value.

The climactic courtroom scene is probably the one Legally Blonde fans remember best. On the surface, we love that scene because in it, Elle uncovers the real murderer, gets Brooke acquitted, and proves she can hack it as a lawyer. These are all reasons to love the scene, but the biggest is Elle’s intelligence. Some critics claim Elle “got lucky” when she noticed witness Chutney’s intact perm, and uses it to expose her. But it’s more likely Elle, who loves all things related to fashion, hair, and makeup, subconsciously notices details like Chutney’s perm. Additionally, Elle has had years of absorbing rules like, “Don’t wet your hair after getting a perm for at least 24 hours.” In a lot of ways, this is no more or less smart than a sports aficionado or Harry Potter fan absorbing reams of trivia. It might seem useless to everyone else, but when Elle needs it, her knowledge is right there, waiting to help her and others. Elle’s knowledge pays off, as does her confidence. Had Elle not been comfortable enough in her own skin to bring it up, Brooke might have been found guilty. At the least, Elle would have continued thinking she wasn’t worthy of being taken seriously. She might never have seen the value in her core interests, or expected more of herself than “to be a Victoria’s Secret model.” By the end of Legally Blonde, Elle is not only a law school graduate, but a fully realized woman who has learned she can succeed outside her comfort zone, but that her personality and interests have a valuable place in the world.

A Final Salute to Smart Ladies

When we think of a smart heroine, we usually think of a girl in thick glasses, buried in a book and avoiding social interaction. Some smart female characters are like that, and they are valuable. Some could be considered role models. However, smart heroines have evolved just like any other fictional archetype. Whether they’re classic bookworms, battling external odds, or nontraditional in their intelligence, we learn to love these heroines from a fairly early age. Smart heroines change their stories and the world around them for the better, inspiring readers and viewers to do likewise. This has been only a sampling of smart heroines, but it’s a safe bet there will be many more in the future.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Legally Blonde is a feminist masterpiece and I will always watch it at least once every two months.

I just watched this movie again, and I love it so much!!! It really is incredibly inspiring.

Genuinely one of the reasons why I went to law school. I think the economy was doing better in her year though

There is almost never a perfect representation of a feminist because nobody can decide on what that woman would be like anyway. It’s like Elizabeth Bennet says in Pride and Prejudice, “I’ve never seen such a woman”. The other characters in the room think she is being too severe, but she’s commenting on the standards that women have to be perfect to be considered worthy (and I would argue the men of her time did too, though in different ways). They aren’t given the credit of being unique and flawed humans first, and have to fit a mold. As soon as a woman becomes unique, she’ll fit within the “ideal feminist” quite as easily as she fit into the “ideal woman”.

Well written and thoughtout post. In my early twenties I worked at a video store. We had to play PG movies on the screens in the morning. Beauty and the Beast was one I put in often. I always thought it was a great story, and I was a raging, punk feminist at the time.

As a child I always looked up most to Belle because she CHOSE to love the Beast. I honestly think this movie had a huge influence on my eventual identification as a feminist. Belle kicks ass.

A good essay. No wonder my daughters all dressed as Belle from Beauty and the Beast during Halloween–I certainly sees them as smart girls who become smart women.

Beauty and the Beast is a very interesting piece to study. Belle doesn’t go to the bottom as the beast does. She’s a better person, who grew up in a better place (although still with her own obstacles, which she overcomes better than the beast does). The beast brings more to the marriage in terms of opportunity (he’s a rich guy with a newly functional castle, after all), but she brings more in terms of temperament and moral compass. He’s the first guy she’s met who has been willing to change his opinion based on her words, and that’s what attracts her. (He reads books she recommends — that’s hot!) The hairiness is barely an obstacle at all.

I haven’t seen the Beauty Beast movie and it’s not really my cup of tea as I want my fairytales to be self-aware and twisted (Utena, anyone?) as opposed to officially ‘clean’ and yet very rotten at heart, as seems to be the case in the live action movie and in the animated Beauty and the Beast movie.

And this live action version immediately makes me think of furries. Or beastiality. I know the Beast is actually a human but all the visuals revolved around a young woman prancing and falling in love with a furry with horns. Yeah.

I do think many of the most prominent female characters in Harry Potter are shown to be extremely talented magically and have great overall strength. I think of people like Hermione, Professor McGonagall, and Mrs. Weasley.

There’s also the question of whether J.K. Rowling was reflecting the world as it is or as it should be. I’m inclined to think it’s the former, although she could have done more to challenge that. But I also don’t know if that would have the same mass appeal. She was asked not to use her first name so that boys wouldn’t be turned off from the books. So there are all sorts of complicating factors here.

A story about a genius little girl that loves books and can move things with her mind; quite simply awesome.

Akeelah Anderson has the heart that so many of us want, that it was touching to watch the movie. I felt like I was really within her life!

Luna totally sucks. She sucks because… she’s just… sucky… and bad.

I think she is one of the most universally-liked characters, but whether she is most beloved I can’t say. There are very few fans of the series who actually dislike her. Maybe you are the only one!

Elle Woods figured out what she wanted, worked EXCEPTIONALLY hard for it, and got into harvard because of it. Most feminist story of them all.

I’m sentimental about movies that touch on father/daughter relationships, so Akeelah really tugged at my heartstrings.

I remember the first time I read Matilda when I was 10. I loved the story. Time hasn’t changed my love for Matilda and I feel like I can appreciate her tale more now as an adult with fresh eyes.

The story of Matilda is just absolutely enchanting; it always has been to me, it was one of my favorite movies growing up.

I LOVED the excellent word choice and the detail in the book. I felt like I could have pushed a print button and the vivid image in my mind could have been made into a tangeable picture.

Kate Winslet narrated the audiobook and she was AMAZING!! One of the best narrations I’ve ever heard.

In HP, the female characters do not seem to always stand alone by themselves without a male character and pretty much every important character in the HP world is male. That alone is a big message that doesn’t get erased away by the few female characters being smart and eloquent.

Some of the themes and messages of in Harry Potter are heavily shaped by JK Rowling’s personal dislike for certain types of people (‘catty’ girls, people who betray others) and, due to her own personal circumstances when writing, certain rewards and important institutions being things she herself longed for (the reverence of mothers as she was in the process of losing her own mother, the family and stable marriages as ideal and universally desirable goals while she herself was starting a new life after an abusive marriage and living in poverty as a single mother).

I also feel she created some great characters (Hermione, Luna, McGonagall) who have entered pop culture as role models, while also having other important notes in her books which are less often picked up on (e.g. the Patil sisters, two non-white girls, being the most beautiful and desirable girls in Harry’s year, and indeed, relationships between people of different races being no big deal, although that’s getting into intersectional territory now).

Wow, really well written analyses. You’ve managed to put a bunch of vague notions about the movies and books I’d had into a very coherent form.

I’ve always thought Beauty and the Beast was the most feminist of all the Disney movies – I mean, she chooses intellectual stimulation over the attention of boys at every turn, has big dreams of doing things rather than marrying someone, is incredibly brave, saves her father, saves herself… she’s one of the few female protagonists with autonomy and confidence who doesn’t get bowled over the minute she has a crush.

With Beauty and the Beast, I want to say my complaint with the story from a feminist perspective is not that I think Beauty doesn’t have agency, or that she chooses to stay with the Beast. There are many articles that do make this point and that argue that the reason Beauty is not a feminist hero is because, despite all her dreams and ambitions, ultimately she ends up as your standard issue married princess. I don’t think this is a very strong thesis myself. Beauty can choose to be a princess and there is nothing wrong or anti-feminist in that choice.

Legally Blond is an example of how femininity can be powerful and strong. Femininity doesn’t equate to being ditsy and air headed. I love that movie!

It’s just kind of unrealistic. Good movie, but practical? No

Stripping away the cheesy aspect, Akeelah and the Bee misses something. Yes, there is a statement about racial discrimination and stereotyping aside from the obvious message of the movie. But the movie is forgettable in that this plot has been done, in a better fashion, with Finding Forrester, Hotel Rwanda, any Sports Movie.

I had high expectations of this movie because of the ratings. I wanted to like it, I really did, but it was just TOO cheesy.

Oh thank you for this article. It’s been over ten years since I last read Matilda and I’d never realised before now how much of the book has stuck with me through my life, from understanding and using the word “phenomenon” at a young age to viewing margarine as a “poor” substitute for butter.

As a feminist I wholeheartedly agree with everything in your lovely article. Excellent analysis of work with surprisingly strong heroines.

This is a wonderful and important article! Thank you for analysing in such birlliant detail a handful of those magnificent girls!

While I grew up with Beauty and the Beast and always enjoyed it, I also couldn’t help wondering what lesson the Beast learns. He was supposed to stop judging based on appearance, but he’s the ugly one and he falls in love with a beautiful girl…

Belle is a feminist heroine because she is a woman with agency, ambition, and humanity who chooses to exercise them in the face of adversity and wins. Those morals and values are not retrograde, they are timeless.

The HP books have sexist roots in them. Jk Rowling has made sexist comments in the past. Rowling views some women as the “right” women. Hermonie is one of those right women. There are very few other “good” females in the book. She openly hated Pansy P who was very opposite of Hermonie.

JK Rowling definitely isn’t anti-feminist, but her feminism only extends to women who she deems worthy.

I dunno, I mean, JK Rowling is only human – can’t she just dislike a person type without it being part of her ideology?

This is a wonderful piece! There is a desperate need for strong heroines and female representation in both film and literature, and this article is such a welcome analysis. I also appreciate that you chose heroines who were all different ages, especially Matilda, and that you included racial diversity by mentioning Akeelah Anderson. Thank you for being so thorough and considerate of the diversity needed to address such an important subject!

I will also note that I feel sometimes that the broader Harry Potter fandom has lost sight of the core ideals of the world Rowling created, when you get to things like harems and marriage laws and super-Harry with his medieval team of witches swooning over him. The whole point of wizarding society was to be a mirror to our own and progressive in some ways, while regressive in others, not as some kind of feudal backwater where all the worst bits of our society were out in force along with other regressive behaviors.

Really interesting perspective! Thanks for sharing!

There was an interesting take on Beauty and the Beast that I saw recently. Basically, that Belle (as with many of the female “heroines” in Disney movies) is not whom the story is about. It’s the Beast’s story, he’s the one who grows and changes and learns to love. She was portrayed as an already self-actualized woman who for some reason still needed a man to make her life complete.

It was something that I’ve never noticed before, that Disney produces a lot of movies about ‘likable’ female stars, but they don’t allow them to undergo growth or personal development like a normal human being.

I would disagree with the interpretation that Belle is self-actualized: for all that Belle has to recommend herself, she begins as a rather insular character, uninterested in anything outside of her bubble. Ultimately, this story is just as much Beast improving Belle in having her see the world around her (along with the servants as anthropomorphic household objects) as it was Belle improving Beast in him becoming more discerning and having him look beyond the superficial. In one sense, Beast was a mirror to how the world saw Belle. The two needed each other.

For me feminism is not set in stone. It is a point of view. Its about who a woman wants to be and if she is able to be what she wants.

Matilda is a gem, Miss Honey is an angel and Roald Dahl’s my hero! <3

I wondered why Rowling didn’t make it Harriet Potter instead.

What a wonderful read! So many powerful women together. Luna in particular stands out. Resistance and intelligence need not to be in your face, it can be gentle and ethereal too.

Great discussion. Feminism takes many forms.

Thanks to all my readers for these great comments! No matter which heroines you do or do not like, the important thing is to keep the discussion going. All great movements and changes began with a discussion, or an idea, or a sentence. Without those, we wouldn’t have these lovely heroines to begin with.

What an interesting article! I really appreciate the thought and effort you put into this piece! The fact that these kinds of characters are evolving and being represented more and more excites me. Although there is still a long ways to go, it’s great to see the public and the industry take notice of why these kinds of characters matter in popular media.

An excellent article with perfect examples! I love how over time, female characters are becoming increasingly dynamic and unique.

I’ve always loved the classic bookworm character. I always feel so connected to them and I appreciate that such a hero uses wit and creativity to solve problems.

i agree with the writer here. some of the things i like about Hermione Granger and Luna are that while they were intellectually sound they were at the same time not cowering behind the male characters for protection. when it came down to a fight they very well held their own. i like that these characters found the perfect balance of being strong and not hostile or dominant.

The parallels among the characterizations of many of these women is astounding. It seems that for a good number of these characters — Belle, Hermione, even Luna — being intelligent is not only a significant plot point, it is also the entry point to mocking from peers. I love how that highlights the need for feminism and how characters are becoming increasingly nuanced.

Surely Shakespeare and The Bible (among other classics) offer examples of “the smart girl” — think of Beatrice in “Much Ado About Nothing” declaring: . “I had rather hear my dog bark at a crow than a man swear he love me.”

Wow! This is a wonderfully-written article, complete with all of the characters that I grew up adoring and wished to be like. I love the parallels drawn between the different characters and the struggles they face, whether racial, academic, or magical.

Wonderful examples of female heroines that exist for themselves, not just to prop up another character. I love the categories you created for them and showed that there’s more than one way to write a smart woman – which makes sense since smart women come in many forms. The popular choices like Belle and Hermione were expected, but I was surprised to see Akeelah and Luna called out as well. A great read!

Interesting read, and I was struck by the fact that the characters chosen in this piece are my daughter’s fictional heroines as she was growing up (millennial, now 26). She went to a feminist, alternative, social-justice oriented girls school, and often had to “sell” her teachers and classmates on her choices…why Elle Woods might be a feminist icon, or a Disney princess, for that matter. Popular culture is not a reflection of our politics, but is often where are political and personal choices are formed and debated. Well done.

Popular culture may not be a reflection of politics, but it certainly comments on them. That has been a staple of pop-culture since its origin. If anything, I think we’re now too afraid of letting our culture speak to our politics. When big franchise works do step out of their way to include base representation of minorities or other ideals, people accuse those works of being ‘too political.’ I think this article and your comment, however, show how important it is that we get a little political, to take our stand and create heroes for people who don’t currently have any.

That classic smart girl is evolving into a badass female character who is not only smart but physically kicks butt. It feels empowering to watch or read about a powerful woman who doesn’t let anyone hold her back. A well written character impacts people. As a child watching Matilda I definitely wanted to be as brave as her. Strongly written characters are so important and you used a lot of good examples in this article

This is a great read! I love how you included different types of smart heroines, such as Hermione (and it was book Hermione, not movie Hermione!) and Luna from Harry Potter. While different, both of them have just as much right to fit into that category.

As a reader, I’ve seen a lot of authors write smart heroines as unbelievably amazing and beautiful. This article would help a lot of them develop their characters into human beings, rather than unattainably perfect people.

This is such a well thought out piece!

It’s sad that we do still find media lacks these intelligent heroines when comparing the small number of them to the undeniably large amount of strong and smart male characters.

Amazing analysis on Hermione and Elle Woods, both of whom are sources of inspiration for young girls and women. I love Hermione and it never occurred to me that she was so dependant on memorizing her textbooks and such because she was afraid of failing in a world that is completely new to her. I can relate to her so much more. Elle Woods is a prime example of how women can be smart and powerful and not have to sacrifice feminity.

I thoroughly enjoyed this piece! Very well thought out and was a delight to read. I never would have thought that some of the characters mentioned would have classified as heroines in the way they did. Well done.

Hi everyone it’s my first time checking out this website, but I’m excited to see what it has to offer! I’ve been writing since I was little…I started out writing in journals when I was around 7 or 9. I would usually make up stories or document my day. Later I wrote in diaries, which by the way, in one of them I documented my entire middle school experience, and the other is based on my freshman year. When I was a junior in high school I joined the poetry team. I performed twice in the school’s theater in front of hundreds of students. I have also performed at various locations in Albuquerque. It wasn’t until recently that I finally got the chance to travel for poetry to compete in a competition known as CUPSI. this year is was held in Houston. My writing evolved as I kept on writing poetry over the years. I’ve also written stories for classes, but none that I’m truly satisfied with. I nevertheless, hope to be a writer for film someday! that said, I was extremely interested in reading this article because I relate to “smart heroines.” I relate to many other types of characters too but deep inside I can honestly say a smart heroine is who I truly identify with.

Excellent piece. It’s so good to see more and more movies and literature being produced with smart heroines. The traditional damsel in distress has done enough damage.

What a great topic to write about! This was really well-written, and I like how you chose different types of “smart heroines.” One thing I noticed was how young all the characters were.The oldest is probably Elle, who is in her early 20’s, so it would be fascinating to see older female characters who fit the trope of “smart heroine.” I guess there would be some overlap with professional women or those in positions of power being seen as threatening or domineering just because they’re intelligent.

Very enjoyable reading. Thanks for such an interesting take on some of my favorite smart heroines.

Great essay. I personally don’t admire Beauty and the Beast for its writing anywhere near as much as its animation (not fond of romance stories in general) but your take on Belle definitely made me appreciate her as a character more.

I also forgot about Akeelah and the Bee until your article. You reminded me about all the social commentary that movie had, especially regarding racial biases and societal pressures placed on kids from an early age.

I appreciated the care you took when defining “smart heroine” for the purposes of your article, and the many branches of that definition—the “marrying of internal and external stakes” section is especially interesting, for example. “To be considered brilliant and beating the odds, the heroine in question must face greater stakes than social struggles, insecurity, or discrepancies between what is real and what could become real. She often faces real-world, external problems such as abuse, bullying, and cultural tensions.” An intriguing contrast!

I also appreciated the range of heroine examples in this article (nice reference to Matilda, one of my childhood favorites). So many more heroines could make this list, as I am certain you know…fun to consider who else could join the conversation. I thought of Anne of Green Gables and The Great Gilly Hopkins when reading.

Thanks for writing!

Yes, this is exactly what we need. More represantation of real characters and real human beings just like women we know in our lives. Better rolemodels that girls can actually look up to.

As someone who was bullied for being smart, my escape was studying the stories of these heroines, very similar to Matilda. This article struck a chord.

I loved these characters as a kid but I hadn’t taken the time to think about them critically as an adult. This was an excellent read. Both nostalgic and eye-opening.