The Philosophical Filmmaking Process of Terrence Malick

Much has been made of the philosophical themes that run throughout the canon of Terrence Malick’s films. Although I will briefly discuss some of these themes, my primary focus will not be on the content of Malick’s work, but rather, on his unique filmmaking process and the evolution of this process through a series of artistic leaps of faith. I will trace the flowering of this process from his innovative magic hour cinematography in Days of Heaven (1978), to his post-production discovery of narrative in The Thin Red Line (1998), to his radical subjectivity and use of camera as character in The New World (2005) and Tree of Life (2011), to his complete abandonment of script and story in To the Wonder (2012), Knight of Cups (2015), and Song to Song (2017.) I will discuss Malick’s unusual (and perhaps exploitive) use of actors and non-actors. And finally, I will argue that although Malick has shared credit with many of the leading actors in Hollywood, with a crew that includes several talented film editors, and with the most celebrated cinematographer in recent history, Emmanuel Lubezki, Malick views his films first and foremost as a collaboration between himself and God.

Winner of two Palme d’Or awards and nominated for three Academy Awards, auteur filmmaker, Terrence Malick, is one of the most distinguished American filmmakers of the past fifty years. He has made exquisite, haunting, enigmatic, and sometimes frustratingly impenetrable films and given us dazzling and awe-inspiring images that have influenced a diverse array of filmmakers like Christopher Nolan, Alejandro Iňárritu, Zack Snyder, and David Gordon Green.

But Malick didn’t set out to be a filmmaker. He began his career as an academic philosopher. Following his undergraduate work at Harvard, Malick pursued his doctoral degree at Oxford University as a Rhodes Scholar, where he studied Kierkegaard, Heidegger, and Wittgenstein. But after a bitter dispute with his thesis advisor, Gilbert Ryle, Malick left Oxford without a doctorate.

Malick continued to contribute to philosophy as a lecturer at MIT. He also published a translation of Heidegger’s The Essence of Reasons in 1969 (Northwestern University Press), but that same year, he earned his MFA from the AFI Conservatory, and turned his attention to the art of filmmaking.

Badlands, Days of Heaven and Magic Hour Cinematography

Terrence Malick’s 1978 film, Days of Heaven, is most often credited with the emanation of “magic hour” cinematography. But the seeds of this fruit can be seen in his seminal 1973 film, Badlands. In fact, although much of that film appears sun-bleached or harsh, the most famous shot of the film, in which Martin Sheen stands Christ-like, rifle behind his head, is a paradigm magic hour shot. The fact that the effect was achieved accidentally or at least spontaneously was, I believe, critical to the genesis of Malick’s method as well as to his collaboration with the Divine.

In photography, magic hour refers to the few minutes from just before sunrise to just after and from just before sunset to just after. More precisely, it occurs when the sun is approximately 4-8 degrees below the horizon. In these few minutes of twilight, the light is soft, scattered, and diffused. Shadows are long, the horizon takes on an ethereal glow, and when backlit, faces are often haloed with golden light.

There is little evidence to suggest that this influential shot was deliberately realized. The production of Badlands was troubled. Working quickly on a $300,000 budget with a non-union crew with which he frequently clashed, Malick shot from morning to night out of necessity. The film, inspired by the Starkweather murder spree of 1957-8, is Malick’s most traditional and accessible and was shot in a relatively traditional manner, although Sissy Spacek recounts that sometimes, Malick would see a cluster of clouds that he liked and they would run towards it to shoot before the light changed. 1

What Malick discovered by accident, epiphany, or revelation, he soon forged into an art. For his next film, Days of Heaven, he replaced cinematographer, Tak Fujimoto (and two others), with lighting specialist Nestor Almendros, who had worked with new wave European directors like Éric Rohmer and François Truffaut. (Almendros would win the Oscar for Best Cinematography for Days of Heaven.) The film was shot in southern Alberta in August, where the magic hour lasted about forty minutes rather than about twelve. It is often reported that Days of Heaven was shot entirely during magic hour using only available light, but in an interview, Almendros clarifies. He says that the daylight hours were spent shooting interiors and in those scenes, in the barn or in the farmer’s house, some artificial light was necessary to preserve the stability of the image since the sun is constantly changing. But almost all of the exterior shots (about 80% of the film) were shot during magic hour. The cast and crew would spend most of the day rehearsing, blocking, setting up camera angles, and waiting. Finally, when the sun began to dip, the film would roll. Almendros tells us that Malick would often continue shooting until well after dark: “Terry would always say, ‘Nestor, let’s just shoot it ….Who knows what it’s going to look like? Maybe it will be great.” 2

And it often was. In the predawn, the diffuse rays of sunlight would shine on the wheat fields and the bounce light gave the faces of the actors a heavenly glow. And after dusk, the yellows and oranges and reds of the sunset would fade and blue wavelengths began to color the sky, giving the action a moody or ominous tone. The amazing scene, in which the entire field is burned in a massive fire, extended well past nightfall and is at times lit only by the fire itself.

Days of Heaven was a triumph, critically and aesthetically, and Malick’s preparation, patience, and faith was solidified into a mystical artistic process. Malick would not use a storyboard or traditional filmmaking techniques again. But it would be twenty years before Terrence Malick made another film.

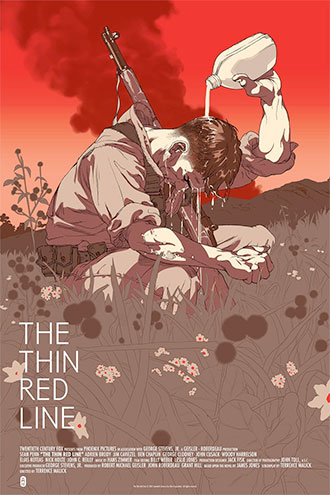

Post-production Discovery of Narrative in The Thin Red Line

Malick returned to cinema with the star-studded 1998 film, The Thin Red Line, an anti-war World War II film (adapted from the novel by James Jones) set around the battle of Guadalcanal. At this point, his two films, his strange hiatus from film, and his increasingly reclusive behavior 3, had made him a Hollywood legend and actors were lined up for the opportunity to work with him.

In the film, Malick cast Adrien Brody, who was to be the lead in the film alongside an ensemble cast that included George Clooney, Sean Penn, Nick Nolte, John Cusack, Ben Chaplin, Woody Harrelson, Elias Koteas, Jared Leto, Thomas Jane, Dash Mihok, Jim Caviezel, Tim Blake Nelson, Nick Stahl, John Travolta, Paul Gleeson, Kirk Acevedo, and John C. Reilly. The production was nearly as maverick and wild as the shooting of Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now. Malick had the actors attend a Boot Camp and camp in the wild without showering for a week at a time. The actors were given real M1s, made to dig their own trenches, and to sleep with their weapons. Although there was no storyboard, there was a script, which was extremely long and constantly being rewritten. Additionally, each actor was given a packet which might include hundreds of pages of ideas, photographs, histories, dialects, lists of books to read, films to see, and music to listen to. Although the actors were prepared psychically, Malick did almost no actual rehearsal of scenes. Elias Koteas reports that when he asked Malick if they were ever going to rehearse, Malick said, “Elias, your whole life has prepared you for this moment.” 4

Toward the end of production, Malick began shooting off-script with no schedule at all. Actors would report to set, be made up and wait to see if their name was called that day and if it was, they would improvise or interact with Melanesian locals. (The film was shot near Port Douglas in Cairns.) In one case, Jim Caviezel reports, “Terry says, ‘Jim, go over and talk to that girl.’ And it’s in the movie!”

Kirk Acevedo: “On any given day, any given hour, you didn’t know what you were going to shoot. He’s very spontaneous. So, the lighting suited this moment, this scene; so that’s what we’re going to shoot ….” Acevedo adds, “His direction is very poetic … catching for fairies and butterflies.” 5

Malick’s directorial style was certainly becoming radical and experimental, but it was Malick’s editing on The Thin Red Line that made his process revolutionary. Although Malick shares credit with three film editors on that film, he is himself, a hands-on editor and he often takes a year to edit his films. While the script centered around Adrian Brody’s character with George Clooney’s character providing important support, Malick discovered in the cutting room that the story was really more about Jim Caviezel’s character. This post-production discovery of narrative follows from Malick’s newfound understanding that image is the first element of cinema. As a visual art, it is not the story, but the image that comes first. And since the image precedes the narrative, and given that the best images are unpredictable and capturing them is an act of faith, we cannot know the story until we review the images.

The Thin Red Line was another critical success and was nominated for seven Academy Awards, including Best Picture and Best Cinematography (John Toll.) Malick was personally nominated for Best Director and Best Adapted Screenplay. But not everyone associated with the film was happy. Adrien Brody, who believed he was the star of the film and gave interviews to that effect, found out at a press junket a few minutes before the première that his role had been reduced to only a couple of lines. Brody said,

I was so focused and professional, I gave everything to it, and then to not receive everything…in terms of witnessing my own work. It was extremely unpleasant because I’d already begun the press for a film that I wasn’t really in. Terry obviously changed the entire concept of the film. I had never experienced anything like that…” 6

Bill Pullman, Lukas Haas, and Mickey Rourke, who said his acting in The Thin Red Line was “some of the best work I ever did” were cut completely from the film and George Clooney’s role was whittled down to only a few shots. 7 Billy Bob Thornton’s 3-hour narration of the film was also completely cut. Martin Sheen, Jason Patric, Gary Oldman, and Viggo Mortenson were also cast in the film but their parts were cut prior to principle photography.

Although Malick receives the highest admiration from some actors like Martin Sheen, who described him as, “a deeply spiritual, bright, articulate man who had a profound influence on me…” 8 and Elias Koteas, who distinguishes his life in two parts: life before meeting Terrence Malick and life after meeting Terrence Malick 9, many actors who worked with Malick began to feel betrayed, exploited, or cheated.

Radical Subjectivity in The New World and Tree of Life and Malick’s Alleged Exploitation of Actors

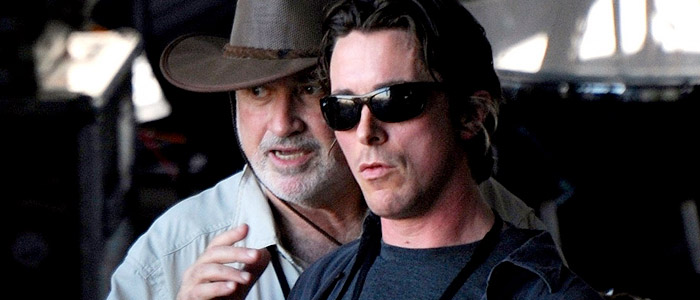

The production of Malick’s next project, The New World, a dream-like reimagining of the discovery of America by Europeans and their relationship with the native population, was full of conflict with actors. Colin Ferrell and Christopher Plummer (who later vowed to never to work with Malick again) expressed great frustration was his process (although Ferrell is warmer to Malick in later interviews.) The sets on The New World were built to allow 360 degree shooting. In a traditional film shoot, there may be dozens of cast and crew members just outside the scope of the shot, but with Malick’s new improvisational style, anyone and anything was fair game. In an interview, Christian Bale remembers a moment on set when Malick was shooting a scene that didn’t involve his character, John Rolfe. Bale was standing under a tree smoking a pipe when suddenly the camera was aimed at him. So he improvised and that footage is in the film. 10

Farrell and Plummer’s frustration had to do with the fact that they were not able to contribute to the film in the way in which they had agreed. Respected actors and beautiful plants and birds were equally important to Malick’s camera. Plummer reports:

“Colin Farrell kept saying, ‘My character, he’s a fuckin’ osprey. That’s how he sees me.’ You’d be playing a passionate scene, and he’d say in that strange southern voice of his, mixed with Harvard and Oxford, ‘Ah, jes’ stop a minute, Chris. I think there’s an osprey flying over there. Do you mind if I just take a few shots?’ I wrote him an infuriated letter because I saw the film and I was hardly in it—he cut my part to shit.” 11

The New World is an exquisite looking film and cinematographer, Emmanuel Lubezki (Malick’s fourth cinematographer through four films), was nominated for an Academy Award, but the picture received only a limited release in the United States to mixed reviews.

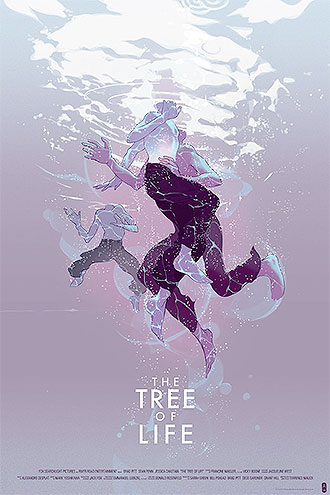

Malick’s next film, 2001’s The Tree of Life, is the most ambitious project of his career. The film is part family drama, part existentialist response to Dostoevsky, part autobiography. The film comes the closest of Malick’s films to providing a philosophical argument although the premises are somewhat obscure. It also contains two of the most extraordinary sequences in his oeuvre. In fact, the first of these, a fifteen minute history of the universe and the Earth beginning with the Big Bang and extending through the development of life and the age of dinosaurs, is one of the most startling and breathtaking sequences in all of cinema.

The film, his last to use a script (or at least a script that he would share with his actors), finds the O’Brien family (overbearing father played by Brad Pitt, grieving mother played by Jessica Chastain, and three sons), living in 1950s Texas after the startling news of the death of one of the sons; and it follows one of those sons, Jack (Sean Penn), in the early 21st century as he attempts to cope with success and alienation. 12(Malick himself came of age in the 1950s in Oklahoma and Texas and lost his brother at a young age like Jack.)

Early in the film, a distinction is made between “the way of nature”, the dog-eat-dog view of the world and “the way of grace”, the empathetic and spiritual way of life. But we see in the film that suffering comes equally to both the followers of the way of the nature and the way of grace, so the question is posed, why should we choose the way of grace? Why should we practice compassion or religiousness in a cold, indifferent, absurd world? Malick presents us with a kind of theodicy, a religious response. Malick’s answer seems to come near the end of the film when Jessica Chastain’s character says, “The only way to be happy is to love. Unless you love, your life will flash by. Do good to them. Wonder. Hope.” But the film doesn’t end here. The film rejoins 21st century Jack as he surrenders to the way of grace and joyfully wonders around his familiar world, seeing things as if for the first time.

Although we get a conclusion of sorts, I stop short of dubbing this a philosophical argument for two reasons: First, the premises in this argument are elusive and it is unclear whether Malick is prescribing the way of grace for everyone, for himself (since the film is very autobiographical), or for these particular characters. Second, the film is poetic, both in narrative and in form. One of the reasons it was not generally well received by audiences is that it feels more like a meditation or a personal prayer than a film (in the sense that most American audiences are used to.)

The Stories of Old, a film analysis YouTube channel, expresses this idea well: “Malick doesn’t just want you to experience The Tree of Life intellectually, analyzing every frame for what he could have meant by it. He wants you to experience it emotionally ….” Malick’s precedence of image over story insists that great art is capable of expressing more than words. The analysis continues: “He fully utilizes the medium of film – meaning that there really is no distinction between the story and the way the story is filmed. What this implies is that every image, every piece of music, however random it may seem, serves a purpose to the narrative.” 13

The first great sequence in The Tree of Life, comes twenty one minutes into the film as Jessica Chastain’s character is questioning the Divine and the relationship between humanity and the Divine. Then, Malick cuts to an extraordinary cosmological sequence beginning with a gentle light, then the Big Bang and the expansion of the universe, and finally the development of life on Earth, from single cell organisms in water through dinosaurs. This sequence begins with grace but primarily here, we witness the shocking and violent way of nature.

Malick’s second revolutionary sequence is shorter and not nearly as spectacular, but it is noteworthy. We begin with Sean Penn’s character, Jack, reflecting on his family, his birth, and childhood. We see, presumably through Jack’s imagination, the warm and romantic beginnings of his parents’ marriage. We see his mother’s pregnant belly, her screams of labor, Jack’s own tiny feet in his father’s hands. We then shift to baby Jack’s POV. Although Malick’s camera alternates between first person POV, over the shoulder POV, and non-POV shots, we experience a radically subjective, phenomenalistic view of childhood. Not only do we see the world through the eyes of a child, we see the world through the eyes of this child, Jack, a character that we have met but may not really like or sympathize with yet.

Malick is not the first or only director to use first-person POV. Hitchcock did it famously in films like Vertigo to show a character’s distress. Filmmaker Gaspar Noe uses it almost exclusively in his 2009 psychedelic film about death, Enter the Void. But Malick’s use of camera as character is unique. Malick (and Lubezski) use innovative wide-angle close-ups and forced perspective to distort images, recalling hauntingly our own overwhelming view of the world as children. And as we see more of Jack’s family and childhood from his unique perspective, we are emotionally drawn in. Malick effectively uses this technique to help us feel empathy.

The Tree of Life was hailed by critics and received Academy Award nominations for Best Picture, Best Director, and Best Cinematographer, but audiences generally found it confounding. 14

Malick’s Experimental Trilogy: To the Wonder, Knight of Cups, and Song to Song

To the Wonder, the first film in Malick’s so-called experimental trilogy, is an odd film indeed and audiences did not respond favorably to it. Even many critics slammed the film. The Long Take, an internet film analysis channel reports that To the Wonder is “generally considered to be to be his worst film.” The analysis continues:

For the majority of American moviegoers, accustomed to the traditional storytelling structures and hallmarks of popular entertainment, Malick frustrates those expectations to an infuriating degree. The further he has progressed in his career, the more he has abandoned the requisites of good storytelling. Anything resembling a three act structure, a clear narrative, and a character arc looks increasingly like a vestigial trait on an evolving organism.

Although I don’t agree with this commentator regarding a lack of character arc, Malick certainly frustrates audience expectations. For instance, audiences (probably with some justification) assumed that this film set in Oklahoma, starring Ben Affleck and Rachel McAdams, would be in English. The fact that the film is almost entirely in French and some Spanish, spoken by Javier Bardem, with only a little background dialogue in English, came as a surprise even to this Terrence Malick fan.

But To the Wonder, a tribute to love and to the strange and beautiful world inhabited by human beings, is an amazing film. The film is narrated primarily by a French woman, portrayed by Olga Kurylenko, and we see the world, especially the American southwest through her eyes. We see America, in all its glory and ugliness, as a foreigner, an alien, a stranger.

It’s unclear whether Malick intended to make this particular sort of film when shooting. In an interview with CNN, Kurylenko acknowledges that there may have been some sort of script, but if so, it was not shown to her: “The script wasn’t present or available to us. I only heard the story from Terry.” She continues, “The scenes … he would tell us [at] the last minute because he didn’t want us to overthink it, to rehearse, so he likes the spontaneity; he likes the mistakes to happen; he likes the real thing.” 15 Christian Bale, who starred both in The New World and Knight of Cups, echoes this idea, saying that Malick’s philosophy on acting is “Let’s start before we’re ready.” 16

Javier Bardem, who plays Father Quintana, a priest in spiritual crisis, says, “I don’t know [who] Marina is in the movie because I don’t have the script. I don’t know how their relationship is . . .. No one tells me. Not even the director. So, the relationship I have with Marina, Olga’s character, or Ben’s, is what I see and what I hear.” 17

Once again, it’s clear that the film took shape in editing. Kurylenko says that Malick “doesn’t film just the story he’s going to make. He films the whole palette. He will do his painting in the cutting room. He doesn’t paint while he films. He only gets the colors.” 18

And once again, this post-production discovery of the film came at a high cost to many of its contributors as actors Michael Sheen, Rachel Weisz, Berry Pepper, Amanda Peet, and Jessica Chastain all had their parts excised completely from the finished film. But To the Wonder also invites another, more serious charge of exploitation. Like in The Thin Red Line, where Malick employs a large number of Melanesian extras, To the Wonder makes use of many non-actors, locals from the town of Bartlesville, Oklahoma, where the film was (mostly) set and shot. Many of these extras are disfigured, seriously ill, seriously impoverished, or incarcerated, their bodies ravished by obesity, disease, or drug addiction, and many of their scenes are sad or disturbing. Although like Diane Arbus before him, Malick (and in fact, much of the cast and crew, including Javier Bardem) spent time with and forged relationships with these local extras, the scenes may have represented them in an unflattering way that they did not understand when they agreed to be filmed. (Certainly most of us would look unflattering juxtaposed against the likes of Ben Affleck and Rachel McAdams.) I don’t believe it is Malick’s intention to exploit the actors or non-actors he employs in his films. Rather, it is a natural consequence of his process that his camera views them all as living props, no more or less important to the finished art than the birds or rocks or trees or waters that he films. Malick is not collaborating with his actors. He is using them in service of his collaboration with God.

In the end, To the Wonder, was a commercial failure and furthered Malick’s reputation as an avant garde arthouse director, too out of touch with mainstream audiences to connect on either an intellectual or an artistic level.

The final step (or final step thus far) in Malick’s filmmaking journey came with 2015’s Knight of Cups and 2017’s Song to Song. Knight of Cups had no script and only a loose narrative, inspired by “The Hymn of the Pearl”, a story from the apocryphal Acts of Thomas. In this film, Malick revisits many of the themes from his past films, such as loss, grief, authenticity, and purpose. To this familiar list, Knight of Cups also adds temptation and excess as Malick comments on the beautiful, shallow, seductive characters of Hollywood and Los Angeles. Malick also advances his spontaneity, improvisation, and use of camera as character. Natalie Portman says in an interview, the camera was another character: “You feel like the camera is a person in the scene, another character, which it is” 19. But with Knight of Cups, Malick’s faith in finding the film went even further. He collected a great amount of B-roll footage via random drone shots. He even went as far as equipping Christian Bale with a GoPro camera and asking him to drive around the city or walk around the beach without Malick or the any of the crew present. The film, though full of dazzling images, was generally a disappointment to audiences, critics, and Terrence Malick fans alike.

Malick’s most recent film, Song to Song, continued this experimental process. The film, which is part relationship drama, part live music event, is set in and around Austin’s SXSW music festival and stars Ryan Gosling, Natalie Portman, Rooney Mara, Michael Fassbender, Cate Blanchett, and Holly Hunter alongside festival attendees and musical acts such as Patti Smith, Iggy Pop, John Lydon, and Red Hot Chili Peppers. As with Knight of Cups, there is something like a narrative and certainly, there are well developed characters with some degree of a story arc, but the films wonders in and out of the lives of these characters without providing much to hold onto. This all seems very deliberate as Rooney Mara’s character, Faye, says, “We thought we could just roll and tumble, live from song to song, kiss to kiss.” Song to Song was once again panned by critics and audiences alike, making Malick’s experimental trilogy a commercial failure and perhaps also a critical one. Knight of Cups and Song to Song certainly advanced Malick’s reputation as an incomprehensible artist. Critic Ben Mankiewicz said of Malick’s recent films, “His movies make me feel dumb …. They make me feel like I’m not smart enough to understand it.” 20 By his own admission, Mankiewicz is not a critic who prizes visual artistry above story. But neither do most patrons of cinema.

Malick’s filmmaking career is characterized by a series of artistic leaps of faith. In Badlands and Days of Heaven, Malick discovers and develops magic hour cinematography, not always knowing what he will get; only believing that it will be spectacular. With The Thin Red Line, The New World, and The Tree of Life, he abandons traditional filmmaking techniques, like storyboarding and rehearsing. Instead, he prepares actors psychically and employs a radically subjective perspective. And in his most recent trilogy, To the Wonder, Knight of Cups, and Song to Song, he abandons script altogether, having faith that through patience, preparation, and editing the film will emerge, led by the ontologically first element of film, the image. Through these acts of faith, through his collaboration with the Divine, Terrence Malick has contributed beautiful films and revolutionary innovations to the medium. In the end, I’m not sure if I can say whether or not Malick’s final leap of faith found consummation. His experimental trilogy has not found favor with audiences or critics as works of cinema, but perhaps as a work of theology or a personal prayer shared with the world, he has succeeded.

Works Cited

- Badlands – Interviews with Martin Sheen, Sissy Spacek, Jack Fisk. YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oMbdY_wiU00 ↩

- Shooting “Days of Heaven”. Filmformfilmpractice. https://www.bing.com/videos/search?q=youtube+malick+days+of+heaven+production&&view=detail&mid=51834696D8353E3B12B951834696D8353E3B12B9&&FORM=VRDGAR ↩

- During his twenty year hiatus, Malick worked on a few screenplays and tinkered with film projects. During this time, he became very private. He continues to avoid having his photo taken, has politely declined all requests for interviews and press junkets since 1975, and has turned down his invitations to the Academy Awards ceremony. ↩

- The Thin Red Line – Actor’s Perspective. YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mCQR4iEihW0 ↩

- The Thin Red Line – Actor’s Perspective. YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mCQR4iEihW0 ↩

- “10 Actors Cut From Terrence Malick Films & How They Reacted”, Jessica Kiang. http://www.indiewire.com/2013/04/10-actors-cut-from-terrence-malick-films-how-they-reacted-99568/ ↩

- “10 Actors Cut From Terrence Malick Films & How They Reacted”, Jessica Kiang. http://www.indiewire.com/2013/04/10-actors-cut-from-terrence-malick-films-how-they-reacted-99568/ ↩

- “Martin Sheen – The Progressive Interview”. http://martinsheen.net/id151.html ↩

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7H1WYej8hP4 ↩

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HK686pye6YM ↩

- “10 Actors Cut From Terrence Malick Films & How They Reacted”, Jessica Kiang. http://www.indiewire.com/2013/04/10-actors-cut-from-terrence-malick-films-how-they-reacted-99568/ ↩

- Notably, this is the first present day sequence in the canon of Malick’s films, which have to this point, all been period pieces. ↩

- “The Tree of Life – Crafting an Existential Masterpiece.” The Stories of Old: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zxnGHhEWXbc ↩

- It’s Rotten Tomatoes critic score is 24 points higher than it’s audience score. Retrieved 3/24/2018: https://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/the_tree_of_life_2011/ ↩

- CNN interview with Olga Kurylenko. “Acting without a script on To The Wonder”: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z-T0ecJpn0w ↩

- https://www.mercurynews.com/2016/03/09/christian-bale-says-filmmaker-terrence-malicks-m-o-is-lets-start-before-were-ready/ ↩

- To the Wonder Featurette. Behind the Scenes Productions. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jZYd_FVPQ_E ↩

- Film editor, Keith Fraase adds: It’s all about “whether it’s honest or not and if any hint of falsity or theatricality comes through, then we abandon that even if it’s more accurate for what the scene is.” 21To the Wonder Featurette. Behind the Scenes Productions. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jZYd_FVPQ_E ↩

- Knight of Cups – ‘The Malick Process’. Broad Green Pictures Featurette. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RxaP6SZ0-84 ↩

- What the Flick?! Official Review of Knight of Cups. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8DihDphqWdw ↩

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Malick made one stone cold classic, Badlands, and two very decent efforts, Days of Heaven and Thin Red Line.

Everything else I’ve seen of his has been various degrees of dreadful. The New World actually made me angry.

In other words, he’s an emperor who started off immaculately dressed, then gradually disrobed until he was completely naked, but nobody dare call him on it because he has this untouchable auteur mystique about him.

Personally I’d rather watch another installment of the Transformers franchise than anything he does.

The New World is a masterpiece, particularly so the extended cut.

The Tree of Life is the best film released since Mulholland Drive.

Sadly, I agree with you about The New World. I mean it didn’t make me angry but I thought it was his least successful film until Song to Song. Actually, although I don’t mention in the article, To the Wonder is my favorite, but I get why most people didn’t like it. So crazy that a film starring Ben Affleck and Rachel McAdams and set mostly in Oklahoma is 90% in French! Not the kind of thing you generally want to spring on audiences.

Hats off to Malick or one of his editors for including the psychedelic punk stylings of the mighty John Dwyer and his diabolically exciting ‘Thee Oh Sees’. You only hear snatches of their weird punk noise in a Malick film but, strangely, they were heard in the background in both ‘To The Wonder’ and ‘Knight of Cups’.

He has the same problem as all the 70s American directors: their strength involved feeding off the major period of art cinema in Europe and Japan in the 50s/60s very closely.

When those sources of influence weakened as their traditions declined in the 80s-present, they tried to look for ideas in contemporary American cinema, which had also worsened.

The key is to still work from the influence of the films of the art cinema of the 50s and 60s, as they contain the seeds of the powerful ideas that made 70s American cinema such a success.

This is a pretty interesting comment. I don’t neccessarily agree with it because I think Malick had a second wind with TNW and TOL.

“The key is to still work from the influence of the films of the art cinema of the 50s and 60s”

Totally agree with this….so much cinema today is lacking in thought and experimentation. In order to look forward you really do have to look back. Moonlight was revered as some kind of new cinema but it was retreading old ideas aesthetically. I watched a film by Miklos Jancso recently which was more adventurous than anything you’ll see today.

What was really weakened in the 80s was the screenwriting, the more actors and producers try to cobble vehicles together the worse this gets.

It’s a mistake to think that cinema is the best way to rejuvenate cinema.

We live in a referentially soaked world via repetition, irony, pastiche, satire, sequels and so on.

The way to forge a new cinema isnt by looking backwards at all. Least of all backwards to older films, which is essentially what we have now. Imagine if instead of making Taxi Driver Scorsese had remade The Searchers or The Big Sleep..he let Michael Winner get on with that one i think god bless him. The old classics are great, but they weren’t made looking backwards nostalgically either. Lets hope for more films where we havent got the faintest shit what is happening, 2001 A Space Odyssey moments. Films like you never saw before.

Agree with most of your comments Claudie. My personal graph for cinema is 50s through to late 60s culminating in a peak – e.g. Persona, Blow Up, Andrei Rublev, 2001: Space Odyssey – essentially experimental films with the latter garnering a massive audience. The previous era fed 70s American filmmaking to its benefit which has since dissipated, and my graph has been going down since then, abetted by Lucas’s industrialisation and the rise of the franchise. Days Of Heaven was a succinct, favourite of mine in which dialogue was muddy and incoherent but Thin Red Line I had few feelings for – the large scale versus internal meditation failed in my eyes, and I love a meditation – pity. I couldn’t get past the casting – John Travolta – either.

The Thin Red Line is brilliant. I only saw it a few years ago, and wow everybody was in it, even in 1998! I absolutely love The New World.

Thank you for your detailed film analysis. The shots depicted in this article are sumptuous!

I can’t say that I always understand Terrence Malick’s film/filmmaking decisions but he is one of the most interesting directors making movies. His movies are visually stunning and he has examined a wide variety of topics and time periods. The Thin Red Line is my favorite Terrence Malick film. I am also excited for his new film “A Hidden Life”, which seems to have beautiful cinematography and powerful themes. Thank you for the wonderful article!

Thin red line was, is, the best ‘war’ film ever

I’ve often wondered with Thin Red Line if using so many stars in small roles was a good idea. It’s a bit of a cameo fest and on first watch I found it distracting.

I do wonder if there was another point however, in that using stars we know in minor roles gives an added dimension by suggesting everyone has a story even in a massive army, and they’re all mourned by someone when they die. So many war films treat death so casually and we rarely get to invest any emotion in bit part characters who are destined to be short lived. Thin Red Line is different in that way.

It’s still a masterpiece even almost 20 years later.

From what i read about the making of the film many of those roles weren’t originally intended to be so small (I think Clooney and Travolta get about a line each, don’t they?). And those characters certainly have more extensive roles in James Jones’s book. I think Malik just left many of them on the cutting room floor (probably much to the actors’ consternation).

He is a great director but there is only so many shots of tress, fields and forests as person can take while the film has no narrative structure.

I saw Days of Heaven when it first came out — not once, but three times in one week. There had been nothing like it before, in my experience, and nothing since for sheer, natural beauty interlaced with a compelling story. The light stunned me. It was like watching a series of paintings projected onto canvas. I still revisit Days of Heaven on occasion, and it has not paled after nearly 40 years (at least not for me).

Malick should have stopped with two films (Badlands & Days of Heaven). Everything that has come since has been disposable. He destroyed his own legacy and is now just a director that made to classic films and another half a dozen that the world could have done without.

I think he’s a director out of time. He reminds me of the 1960’s and 1970’s european directors, like Visconti. Slow paced and beautifully shot. Telling stories through visuals. He also would have made a brilliant silent movie director.

Cinema audiences also used to have a greater attention span. Even in blockbusters, like Lawrence of Arabia, Lean would spend an age setting up a scene and moments of tension. There’s no way a director could get away now with the meeting with omar sharif and O’ Toole at the well. There’s no way you could even spend the time on a scene like the plane/crop scene in North by Northwest. But thankfully even a flawed Malick is a thousand times better than most of the turgid dross I see at the cinema now.

I think there is still a place for the children of the 50s 60s 70s, but I;m not sure Malick is him/her.He does seem out of time. Bergman and Antonioni are my touchstones, but i’m enjoying films by Refn etc in a way that makes Malick look passe.

A good essay, nice develop of one director’s films.

Tree of Life left me in an emotional heap. I watched it twice in a row — the second time with my roommate — because I loved it so much. That movie has stuck with me through the years. I think of that movie and Aronofsky’s The Fountain as bookend pieces. They have similar themes and an ageless feel.

Thanks, Chad. Never thought of it’s similarity to The Fountain, but great call. Both feel like cosmic, poetic prayers.

Days of Heaven is one of the greatest American films of all time. Now, I liked Tree of Life but don’t really have much interest in going back to it and was not remotely interested in his last two movies. I suspect Malick might’ve reach a shark jumping moment in his career or at least he’s got stuck with the themes he’s covering (he’s probably the US’s nearest equivalent to Tarkovsky but it all seems a bit samey). Casting a bunch of idiots who can barely act doesn’t help.

What is his obsession with water about? I never figured it out.

I don’t know. Maybe without it there would be no life. Perhaps he likes the way light reflects on its surface.

The reason why Badlands and Days of Heaven appear to be better than the subsequent films may be due to the lack of money Malick had at this stage of his career, camera-shy Malick may even have appeared in the first film to save money on an actor. Once he had money to make the films he wanted, his typical modus operandi would be to shoot hours of film, often at random when the actors were resting on the set, and then edit it down. The Thin Red Line is a fascinating film about the Pacific campaign, and it has its moments particularly the battle sequence with Nick Nolte and Elias Koteas, but the film has no linear narrative, and the last scene is obviously tacked on with no real purpose. The New World also has its moments, but a thinly layered story. If anything, The Tree of Life is Malick’s most coherent recent film, juxtaposing the life of nature with the life of grace, but on a religious/Christian view of life that may not appeal. Yes, he is a self-indulgent director, but that is what you get with Malick and you are free to ignore his work and it won’t lessen the quality of your life.

Agree to some extent. Financial pragmatism often ends up in taut creative splendour, but industry reverence and an open cheque book often end up in creative masturbation. For me that is what has happened and C21st Malick doesn’t rate it for me, there are dozens of European and Asian directors who could do better with the money.

Don’t get me wrong – Badlands and Days Of Heaven are awesome but I feel he is lost in this century.

Thin Red Line is worth watching for its portrayal of Japanese soldiers alone- stunning. So too for the pained expression of son when trying to please father in The Tree of Life.

Okay, so the general consensus seems to be that Malick made three masterpieces: Badlands, Days of Heaven and Thin Red Line.

How many other filmmakers of Malick’s era can you say made three masterpieces? Not many: Scorsese would be one, Coppola another, Kubrick, I’d say Altman and Woody Allen and you can add your own personal selections, but very, very few filmmakers manage to produce three masterpieces. It really and truly is quite an astonishing achievement. Even the mighty Orson Welles, from a different era, could only mange one masterpiece (maybe two if the hype about the uncut Magnificent Ambersons is to be believed).

The point is, these geniuses don’t owe their audience anything and it’s a bit narky and unseemly to be clamouring for replications of their masterworks — c’mon Utzon, give us another Opera House you pretentious has-been wanker!

Rather than agonising over old Man Malick’s creative travails, perhaps one’s time would be better spent seeking out the masterpieces being made by new young filmmakers?

I think any ‘genius’ owes his audience good art. You do not automatically earn the right to shit all over people if you did something good once.

This is not in reference to Malick but to your proposal.

There’s no-one else making films like him. and compared to the drivel hollywood is pouring out as a cloning device of plots and structure and “characters” he’s still a tornado of fresh air. look at his influence, his out from ’05s The New World onward, and see the film makers who have taken inspiration – Moonlight, American Honey, the revenant just off the top of my head. I find his films entrancing, magical, beautiful, haunting and lots of other nice words that are generally scorned, or looked for only once in a while. that his films don’t offer easy and immediate explanations and ways in seems to be such a problem with the increasingly homogenised rotten tomatoes obsessed critical community; it can’t be because he’s being repetitive, as directors such as woody allen, zack snyder, any marvel product, get a fairly free ride. people might have expectations that everything he produces will be a revolutionary game changer – something that makes their review easier to write, giving it a hook and USP. He belongs in the ranks of Bergman, Antonioni, Ozu, quietly creating his own world and vision away from Hollywood. (though i’m sure he’s enjoying using a selection of Hollywood’s best actors to put them through something they’ll likely never have to do again).

I couldn’t have put it better myself, Alessandra.

Yep, I mean he has actually invented his own cinematic vocabulary, like Kubrick and some of those others you mention, to criticise him for then using it, is like whining about Scorsese’s use of whip pans, pop songs and violence etc.

We’ve already covered my love of Malick’s work in the editorial stage, so I won’t repeat myself. Your article is excellent. It’s a riveting read and well presented. I’ll be sending a link to this article to various friends.

Thank you so much. Your interest and encouragement means a lot.

Tree of Life is a masterpiece and To the Wonder is bloody brilliant too.

‘The Thin Red Line’ was a film that made me question myself: “No, it can’t have been as good as I that…..”. I saw it again, just to check, and yes, yes it was. ‘The New World’ was pretty great although Malick’s knobbing around with its running time suggested a lack of confidence. I saw the longest cut, as well as the shorter, and the Blu-ray longest version played very well.

It’s hard for me not to love an artist who just gets more and more extreme and abstract as time goes on, when many others get too fat, lazy and comfortable, turning in will-this-do?-style dullness.I think it was John Lennon who said that “…avant-garde is the French for ‘bullshit'”. Maybe Malick benefits from the comparison with the leaden stuff tossed out by others when, in actual fact, his own stuff isn’t very good either, just a different brand of rubbish? I don’t know for sure but I do know that I love his work.

Adore all his films up to and including Tree Of Life. I can’t see me going to see another of his for fear of ruining further my mindblown memories of his previous work.

Those 12 minutes of origin of life in The Tree of life was a masterpiece. It certainly beats the origin of life scene from Prometheus where a bald naked muscular man eats caviar and disintegrates into a waterfall.

Love Badlands and The Thin Red line.

Thank you for all the great comments. I’ve been traveling and haven’t had a chance to respond to specific comments yet. But I’ve enjoyed reading and very much appreciate your feedback. More soon.

So excited for Malick’s new film, ‘A Hidden Life’. Trailer looks amazing! https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aC27zIAdPjU

His method doesn’t seem to have changed much. August Diehl says: “There are no breaks for light changes or counter shots, you are always on the whole time — that makes you after a few weeks just living it,” Diehl told TheWrap’s Steve Pond at the Toronto International Film Festival. “You live the whole thing, you are breathing it, you are not thinking abut particular scenes — you think about the life. You think about the hay that needs to be changed or working on a farm”

“I remember one day, I was laying on a meadow sleeping because I was so exhausted and the camera was here,” he said, pointing to his face, “and they are filming everything they can have.” — https://www.thewrap.com/hidden-life-on-terrence-malick-film-no-breaks-video/

The Thin Red Line is a work of art, and The New World is staggeringly underrated. After Tree of Life I must admit I lost interest. Still, I might come back to him.

Terrence Malick is a birthday twin and I thus anyway have a soft corner for his work, not that his films do not deserve it by their own merit. Interested people should also check out his ‘Voyage of Time’.