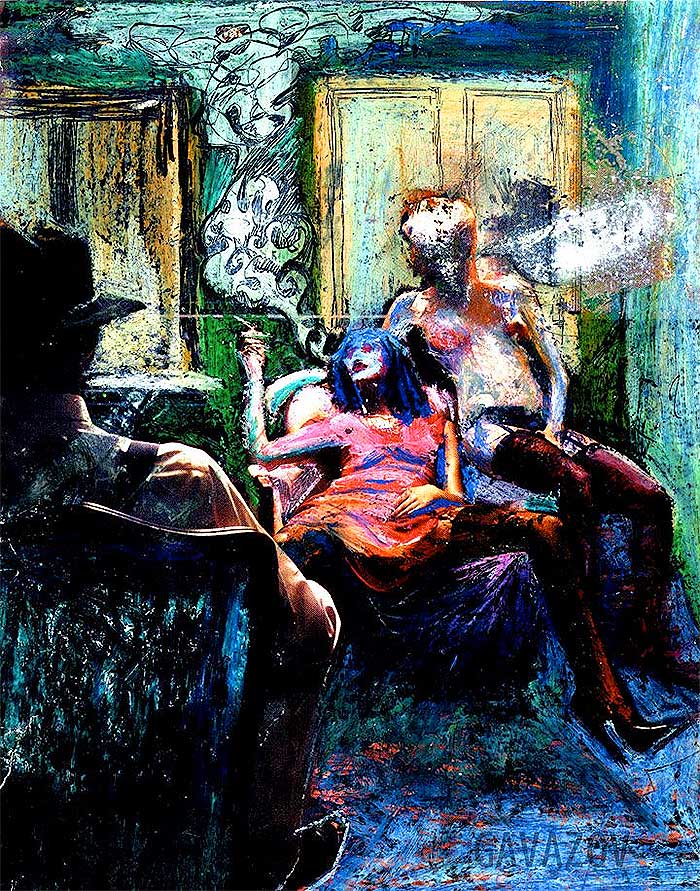

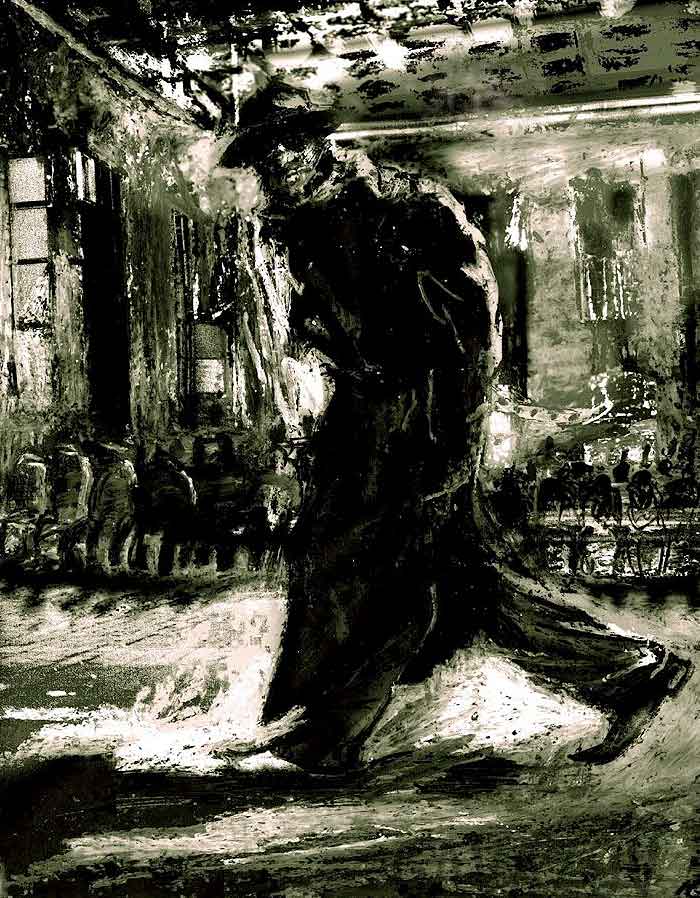

Gavazov and the Eastern European Art Scene

Delving into history, especially that of art, is complicated and often entails a great deal of imagination. The historian is given access to separate, sometimes random, pieces of information, and is then required to construct a credible, useful narrative from the partial evidence. In my mind this resembles the task of putting a puzzle together – sometimes the pieces get missing, there are gaps, yet the whole picture could still be visible if one manages to put the available pieces in place.

The Eastern European Puzzle

The Eastern European contemporary art scene’s origins and development offer grounds for a unique and colourful puzzle. Recently, many scholars from diverse parts of the world have turned their academic gaze towards the East, in the hope of bringing the puzzle together and thus foregrounding the place of performance art in the region. 1 The history of Bulgarian performance is heavily fragmented and among the most difficult ones to handle. Despite efforts, its picture is blurry. In major works about performance in Eastern Europe, Bulgaria does not take more than a couple of paragraphs as opposed to other countries which, for various reasons, allow for a broader exploration of this history. For example, Amy Bryzge’s influential book Performance Art in Eastern Europe from the 1960s (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2017) and Piotr Piotrowski’s In the Shadow of Yalta: Art and the Avant Garde in Eastern Europe 1945 – 1989 (London: Reaktion Books ltd., 2009) include examples of Bulgarian performances and artists in an attempt to map the various practices in the region. Yet this general overview remains comparatively descriptive and superficial.

Some of the few people to publicly address this deficiency of a critical discussion were the art historian and curator Vera Mlechevska and the artist Dimitar Shopov. In 2011 they embarked on a collaborative project with the aim of highlighting the hiatus in Bulgarian art history stemming from the ‘national complex regarding the lack of an avant-garde tradition’. 2 This lack is evidenced by the fact that introduction to new, experimental practices occurred relatively late in Bulgaria compared to other European places. For example, the first documented happening took place in the countryside, away from any authoritative and institutional view in 1985. This same year, the Arts Council in the UK ‘developed a new promotion scheme that helped to legitimize performance art and made it possible for other unrecognized forms’. 3 This interesting juxtaposition of the two events presents the distance between the East and West and their respective socio-political environments – it shows the belated phase at which Bulgarian performance art was at the same time when other parts of the Western world were beginning to accumulate better support. While experimental art in Bulgaria was starting to make insecure baby-steps, performance in other parts of Western Europe was at various stages of learning how to run. This is also evidenced by the lack of terminology in Bulgarian until recently. The word ‘performance’ is gradually becoming more accepted nowadays and serves as an umbrella term to indicate and historicise the heterogeneous and complicated developments of the avant-garde and the conception of performance art in the region. Some art historians, like Piotr Piotrowski, attribute this delay to ‘the absence of a tradition of independent art’, owing to the oppressive regime and art’s collectivisation by the state. 4

Historical Context

The geopolitical status of the country in the aftermath of World War II was a major contributing factor to the regulated progress of the arts. Being a satellite state of the Soviet Union, and therefore having some of the strongest political, economic and military pressures imposed on it, the Bulgarian government implemented strict regulations on all forms of cultural expression. Officially, no occasion was allowed for experimental art which might carry the potential for radical thinking and activism. All such activities were forbidden and because of the risk only rarely done in private with no material traces left. The absence of documentation, however, does not always mean the complete inexistence of performative work. Some historians argue that there were artists who worked in this mode, but who simply could not produce any evidence or leave any traces for the future generations. The strong links with the USSR and its communist ideologies demanded that the government controls each area within the socio-cultural sphere. Artistic production was severely censored, and artists were wary of putting themselves under the wrong spotlight.

The Birth of an Artist

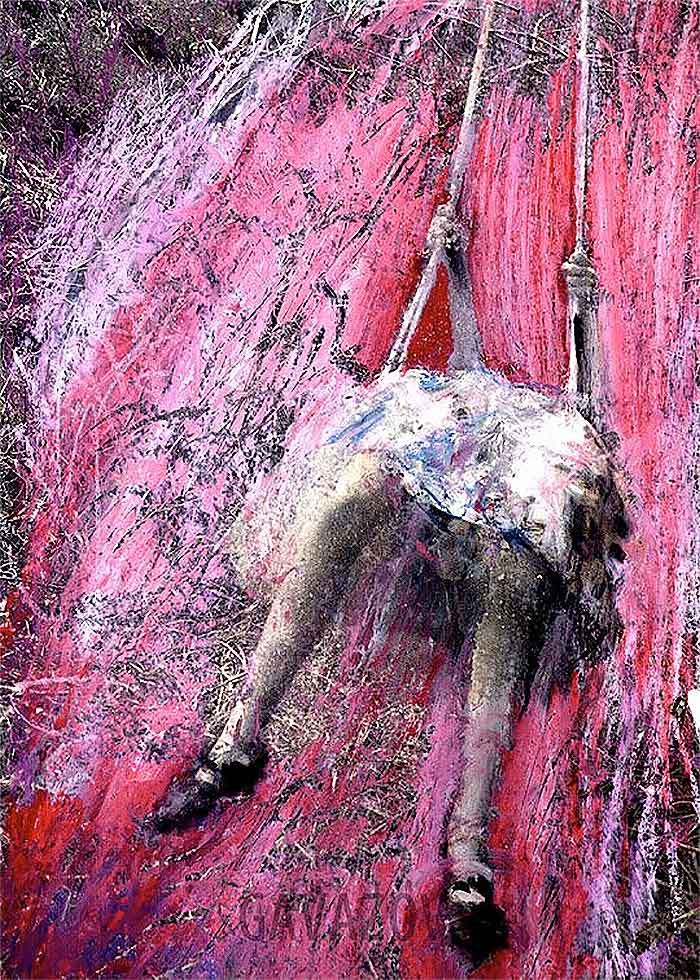

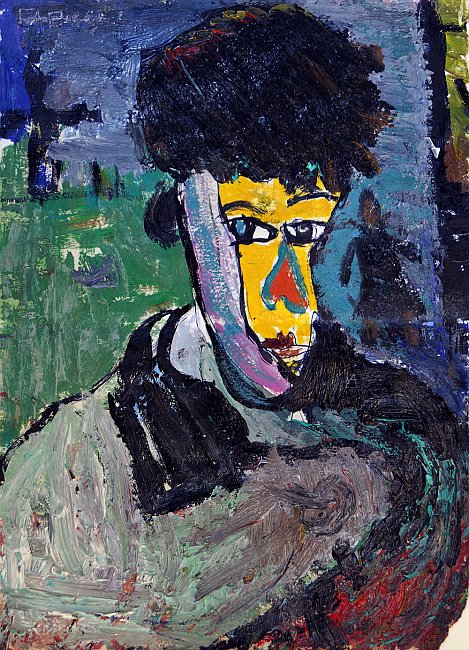

The project, which began as an experiment by Shopov, works on many levels. One of them being an attempt to fill in the gaps in the scattered and patchy history of performance. Shopov imagined a different past in which a famous Bulgarian artist lived and worked. Through performative lectures, exhibitions and the publishing of a biography, Milosh Gavazov was born. He is presented as a notable avant-garde artist, the person who ‘has done everything and pioneered everything one could imagine’. 5 He is often described as a painter, but his works encompass a variety of mediums, shaping his individual practice as an idiosyncratic synecdoche for the development of the arts in general. The impulse for this is described by Amy Bryzgel stating that ‘whereas most post-communist and post-socialist countries are eager to showcase those artists who continued the traditions of the avant-garde, Bulgaria carries the stigma of not having many of those traditions (at least not until the 1980s)’. 6 As a consequence, Gavazov embodied this hiatus in a playful and ironic way and is now seen as the incarnation of an alternative national past – a past imagined and told through his own personal history.

Milosh Gavazov

Supposedly born on the symbolic date of 15th September (the first day of school in Bulgaria) in 1908 (a year before the first Futurist manifesto), Gavazov’s life is imbued with purposeful inconsistencies, critical metaphors and incredible events. Not much is known about his childhood and there are various speculations regarding his death (some theories even claim he is still alive). He has travelled all around the world, worked in New York, had a studio in Paris where he had many followers and students, found personal and professional success in Bujumbura, placed the beginning of many contemporary movements within the arts and created unprecedented works in terms of both scale and essence. The project is presented as a humorous undertaking, the lectures being filled with laughter and light-hearted conversations among the presenters about Gavazov’s unimaginable achievements. 7 He is described as an egocentric and narcissistic artist, the founder of many influential movements, like destructive positivism and neo-constructive perspective, which supposedly left a radical imprint in art history. Furthermore, these fictions, presented as facts, do not exist on their own but are underpinned by a careful selection of real and imagined people (scholars, curators, artists, academics and critics) who construct the mythical life of Milosh Gavazov. This is the overt narrative presented by the authors. There is, however, another narrative, or meta-narrative, which is hidden and accessible to the readers and audiences only through their expanded understanding of the communist regime and the social atmosphere of the post-war period in the Balkans. This disguise indicates the project’s much deeper meaning by offering a broader critical field which enables a remodelled reading of history. The irony is derived from the fact that this narrative was not (and could not have been) possible in the original history of the country. It can only exist in the imagination of the present generation who have the privilege of using the historical distance to analyse the realities of the time. They imagine a past in which free artistic expression and experimentation was possible. Gavazov exists not only to ridicule some of the elements of cultural indoctrination, but to be an exemplar of such an alternative past.

Western Framework and Parallels

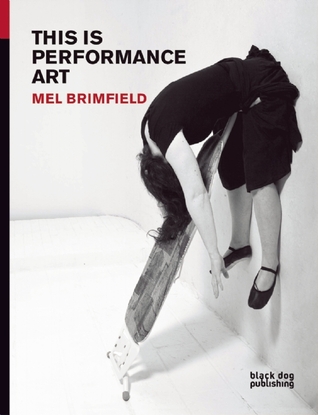

A similar critical strategy can be traced in the work of Mel Brimfield and mainly her notorious documentary This is Performance Art. In the foreword to the book carrying the same name, Matt Fenton describes her project as if he is describing the work of Gavazov, saying that it is ‘somehow entirely tongue-in-cheek and completely serious; it is simultaneously a sly insertion into the opaque history of performance art, (…), and a carefully constructed document of an event that never was. 8 Brimfield’s project is a critique of the slippery and unreliable historiographies of performance art deriving from the impossibility to have an objective overview when the documentation is partial. She imagines that past in a completely disordered manner, looking at the task of a historian through the prism of her own creative spectre. She is arranging events, people and works, as well as constructing new ones, thus introducing an alternative history of Western performance.

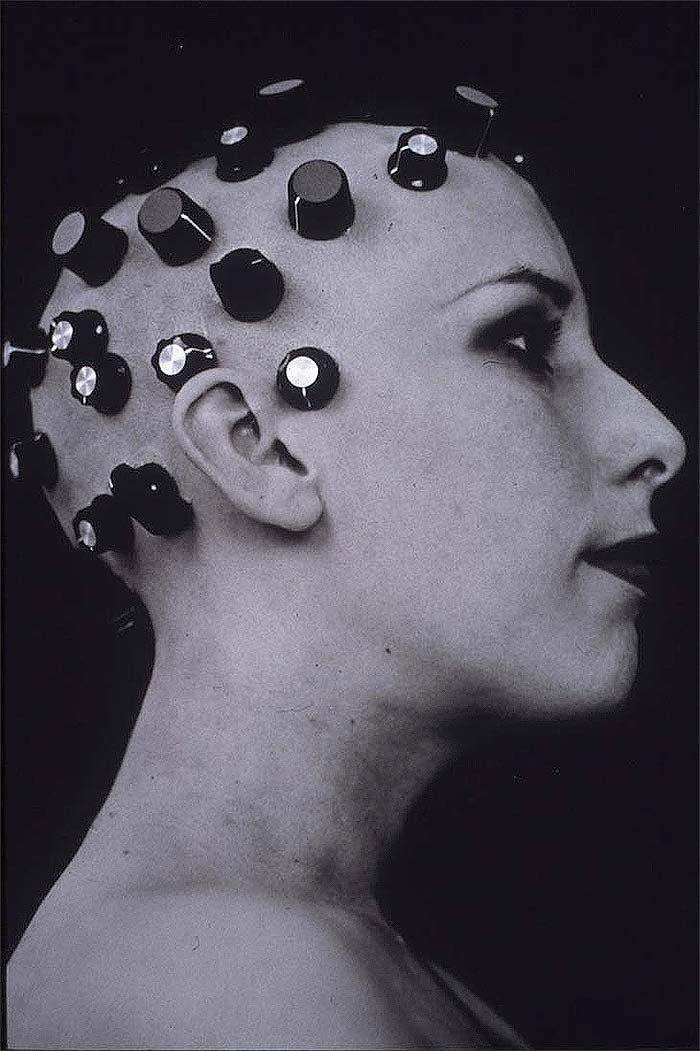

Another example of this approach, but directed towards a personal professional history, can be seen in the project Connotations by Hayley Newman. Through performative photographs the artist intends to create and manage her own individual narrative. Despite being distributed as documentation of performances taken between 1994 – 1998, the images in Connotations are simply a series of imagined events and performances the artist wanted to create but never did. Consequently, the images with their dates, collaborators and descriptions are entirely fictional and most of their making did not take more than a week. This was aimed at constructing her ‘own subjective performance canon’ by ‘creating opportunities that did not exist at the time’. 9

Both of those works present a connection with the same subject-matter. They attempt to insert a critical disruption in a certain aspect of life and thus create some sort of an alternative past. In the first case this aim is concerned with the field of performance art in particular, while the second case is entirely personal. The seductive qualities of confusing time, deceiving the facts and creating one’s own narrative, however, carry very distinct implications in the West and the East. Mlechevska and Shopov’s project expresses the same consideration as the works by Brimfield and Newman, but Gavazov’s personal narrative is also directed towards a broader socio-political critique. His existence transcends both the scope of performance art history and that of individual canonisation. The project moves on a larger effective scale, exploring numerous layers of the past, as well as influencing the present. It alludes to the realities of social, cultural, economic and political life in Bulgaria during the communist era, while also proposes an unconventional approach to the distribution of knowledge in the face of the performative lectures. Disguised as a sarcastic string of events, the complexity of Gavazov’s true essence is unwrapped as he ‘wanders between the unknown and the known, between the foreign and domestic, the naive and academic’. 10 He imagines the unimaginable, creates the impossible and speaks of the unspoken.

Socialist Realism – Essence and Issues

Freedom of speech, as well as of press and artistic expression, was one of the main elements that circulated within the formal rhetoric of the countries in Eastern Europe during the post-war period. This was, of course, as long as the things expressed propagated the relevant ideals and beliefs. Until the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991 and Bulgaria’s consequent breakup with the communist ties, the regime guaranteed those freedoms by law only if they were ‘in conformity with the interests of the working people and in order to strengthen the socialist system’. 11 This consequently entailed strict demands on artistic production.

The official artistic method which everyone had to follow and abide by had the equivocal name Socialist Realism. Michael Kelleher maintains that defining it ‘can be difficult, as it is a concept more than an artistic style.’ 12 The essential purpose of the method was to ensure that artists, writers and everyone working in the cultural sector supports the platform and ideology of the Soviet regime. The method was also applied not only to the regulations of literature, as is often mistakenly accepted, but also guarded the creation and distribution of the arts in general. The government controlled the radio, films, theatre, media and newsprints. Historian R. J. Crampton maintains that after September 1944 ‘every aspect of [Bulgarian] national life seemed to be refashioned on the Soviet model: education, culture, the economy, architecture and the military.’ 13 Every deviance from the general model was severely punished. The years of Stalin’s dictatorship in the USSR were marked by severe oppression, violent purges and constant prosecution and censorship imposed on the people. A similar model of rule, one not so intense in scale, was translated in Bulgaria through Todor Zhivkov – leader of the People’s Republic of Bulgaria from 1954 until 1989 and the General Secretary of the Bulgarian Communist Party.

Many significant works of art never saw the light of day and existed only as apocrypha. If, however, artists decided to take the risk and distribute unsettling, radical art, despite the legal restrictions, they were bound to get imprisoned, sanctioned, forced into exile or in some cases even sentenced to death. Cases of famous artists gone missing and then found dead (without a trial) were not a rarity. One such case is the story of the experimental writer Geo Milev who was taken to a police station for a ‘short interrogation’ from which he never returned. His fate remained unknown for 30 years and his body was found in a mass grave near the capital Sofia.

The Eastern Landscape

During the late 1960s – the period when performance art allegedly formed as its own category – the situation in other parts of the East was seemingly different. In former Yugoslavia, for example, students organised massive demonstrations demanding social justice and protesting against economic reforms. One of the results was that students in Belgrade were given a platform, the famous SKC (Student’s Cultural Centre), where they could develop and create their own work. Despite having a lot of shortcomings and regulations, this model gave the opportunity for free experimentation and autonomous practice. Artists started experimenting with various techniques, merging mediums, performing live, going out in the streets. Yet this artistic breakthrough was still politically conditioned and tied to national sensibilities. Bryzgel points out that:

While across the Eastern Bloc experimental artists were granted various degrees of freedom, it goes without saying that any criticism of the government or leadership would have serious repercussions – even if this criticism were merely suspected, as opposed to real. 14

Artists throughout the East tried to find ways in which to carve the path for new explorations and to gain independence despite the limitations. In Bulgaria, however, experimental artists had very limited powers and agency. All art was to be created in order to serve the state, i.e. the dominant communist party and its ideology. Gavazov, although ironically described as a ‘sworn socialist’, turns out to be the only one who fully succeeds in diverting this. 15 He escapes this pre-written faith because he had not existed then. He acts on the past only through his existence in the present. The performativity that the authors employ in their lectures is the critical tool with which they bring the artist to life and paint a different picture of the past. The word ‘performativity’ is derived from the writings of J. L. Austin in How to do Things with Words (Oxford: OUP, 2009). The idea being that certain utterances, in the appropriate circumstances, can be equal to performing an action. In other words, to say something is to actually make it. In the case of Gavazov, the lectures (and later the book) are the realm through which he exists and implements his powers.

Disguised as a series of actual statements, the stories Shopov and Mlechevska tell are in reality a fictional performative narrative. Despite being an art historian, however, Mlechevska does not pretend to be in the capacity to make history in terms of claiming any institutional recognition or factual truthfulness. The stories are a hoax, the facts are wrong, but the ironic gesture of lecturing on Gavazov’s life and art is more than just a mockery. It is transformed into a critical and political gesture, one that directs the public’s attention towards the disparities and gaps within the cultural history of Bulgaria’s avant-garde tradition.

The Meta-Narrative and Its Critical Effects

This is where the power of Gavazov lies. The meta-narrative that Mlechevska and Shopov embed in the stories about his life and art has the capacity to express the realities of the regime in a way that cannot be extracted from history books. The pair does not try to make the stories sound real, because the effects of the work are conditioned precisely by this transparent falsity. Finding themselves in this particular situation – where they are being denied the history and tradition of performance, they take matters into their own hands by creating this history in the present. Shannon Jackson points out that ‘the word performance derives from a Greek root meaning “to furnish forth,” “to carry forward,” “to bring into being”.’ 16 Therefore, the project seeks not only to bring Gavazov into being and thus comment on the past, but also to carry the tradition of performance forward and to develop it as a critical approach for the future. In this way, the authors disrupt the orthodox manner in which artistic production and institutionalisation happens. Their effort in expanding the practical scope of history and of contemporary art does not rely on any authoritative bodies, but on their sheer imagination.

Commenting on the project, Mlechevska says that ‘the precious thing in Dimitar Shopov’s pseudoscientific restoration is the reflection on a series of cultural facts by compensatory filling in of the missing Bulgarian history.’ 17 Moreover, through this filling in, the project foregrounds the basis needed for the further development of other experimental practices and genres.

Gavazov speaks from the past, but his voice reverberates in the now, breaking the decades’ long silence. His fictional actions and achievements are void in and of themselves, but the very act of performing this nothingness is where his analytical, critical powers lie. He speaks of a history which is denied and absorbs everything which is forgotten. He creates this past anew in order to compensate for the cultural hiatus caused by the regime. Despite being imaginary, his stories provide real lens through which to read, write and talk about the losses in Bulgaria’s consciousness which shape its current position alongside the Western world’s art scene. Therefore, the creative project manages to expand the scope of its own artistic bounds (and conventional bonds) in order to add the missing parts in the puzzle. It is seen not simply as an experimentation in form and artistic style, but also as a tool for unearthing the gaps in Bulgaria’s art history, such as the ‘lack of underground and avant-garde during certain historical periods.’ 18 Gavazov exposes the realities of the post-war period and simultaneously creates a context for himself and others in which to exist, create and thrive.

Works Cited

- When using the word ‘East’, I am referring to the Eastern European countries included in the term ‘Eastern Bloc’ – a division which occurred as a consequence of the Cold War. ↩

- Amy Bryzgel, Performance Art in Eastern Europe since 1960, p.331. ↩

- Jennie Klein, ‘Developing Live Art’ in Histories and Practices of Live Art, ed. by Deirdre Heddon and Jennie Klein (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012), pp. 12-36, p.20. ↩

- Bryzgel, Performance Art in Eastern Europe, p. 39. ↩

- Bryzgel, Performance Art in Eastern Europe, p.331. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- A brief excerpt from one of the lectures can be found here (with subtitles): Vera Mlechevska, Gavazov, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7Wtcl7prkqA> (2014) [accessed 04 January, 2020] ↩

- Mel Brimfield, This is Performance Art (London: Black Dog Publishing, 2011), p.8. ↩

- Hayley Newman, ‘Connotations – Performance Images (1994-1998)’ in Live: Art and Performance, ed. by Adrian Heathfield (London: Tate Publishing, 2004), p.168. ↩

- The Destructive Positivism of Milosh Gavazov <http://uniart.bg/the+destructive+positivism+of+milosh+gavazov%2B%2B%2B%2Bevents/1/MNevctKHY5KHcZOHYNWvcBe3Y1KLcBe-YVafMBebMZeXctKHclafMJefYFefI5KHcZK7> (2018) [accessed 04 January 2020]. ↩

- Constitution of the USSR 1936 (Article 125), partly reprinted in James, C. Vaughan, Soviet Socialist Realism: Origins and Theory (London: Macmillan, 1973). ↩

- Michael Kelleher, ’Bulgaria’s Communist-Era Landscape’ in The Public Historian, Vol. 31, No. 3 (University of California Press, 2009), pp. 39-72, p.63. ↩

- R.J. Crampton, A Concise History of Bulgaria, 2nd edition (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005), p.190. ↩

- [1] Bryzgel, Performance Art, .19. ↩

- Palić, Gavazov, p.35. ↩

- Shannon Jackson, Professing Performance: Theatre in the Academy from Philology to Performativity (Cambridge UK: Cambridge UP, 2005), p.13. ↩

- Stefan Ivanov, Who is Milosh Gavazov (26 April, 2012) < <http://siv.sofiascape.com/?p=4277> [accessed 11 December 19]. Translation mine. ↩

- Ivanov, Who is Milosh Gavazov. Translation mine. ↩

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Very interesting article that shows transformations in art brought on by globalization.

East european art is empowering!

Never ever heard about Milosh Gavazov, but now I want more. Thanks for this writeup.

I feel there is a profound rise in Eastern European art. Younger artists—tired of the lack of support from cash-strapped ministries and museums—are curating and promoting their own shows and hosting exhibitions in everything from small studios to abandoned nuclear bunkers. In fact, one of my favorite exhibitions was an experience last year in Romania.

Sharing this article with my colleagues at university, thank you.

There was a tendency in the first post-communist decade for East European Art scenes to respond primarily to the West, while second decade was dominated by looking introspectively at everyone’s local art histories.

Some neo-avant-garde art under Socialism.

but this is not fake…this is true… Gavazov could be a real artist 🙂

Dimitar, if this is you, then I want to say I am intrigued by your art.

may be because sometimes the art can be real…

thx Mort

Gavazov has many, many effective and active layers (as an artist, as a concept, etc.) I just tried to unpick one of them from a specific angle. True/false, real/imaginary, authentic/fake it’s all blurry and is merging and I feel this is what’s truly powerful about him and his work 🙂

You did good!

Thank you for the comprehensive article. I am inspired now to read more about Shopov and the Eastern European art scene.

I don’t know about you but if you look at artworks from the 60s, 70s, and 80s, sometimes it is quite difficult to tell whether the artwork is Eastern European or Western European. That kind of says a lot about the political climate of the times.

Art from Central & Eastern Europe is considerably more rich and expresses diverse views.

These pieces of art creates a challenging scan of social transformations.

I wish more art from our country would be featured like this more often. Many galleries in countries belonging to the “Eastern Bloc” (Poland, Romania, Bulgaria, Ukraine, Hungary) have been struggling to support contemporary arts, following the fundamental shifts in the 90s. They had to invent their own rules, to adapt to a system that had been mostly shared by artists approved by the state versus artists working rather as outsiders. The tides are changes now though and that is something to celebrate.

What country do you mean by “our country”?

“Gavazov” helped to create a stronger sense of identity for Bulgarian art.

Great treatment of this topic.

As a contemporary artist currently working in Eastern Europe, I thank you for writing this and bringing awareness to art here.

Sofia’s art scene is properly flourishing! A new wave of creatives are breaking it.

Interesting how Gavazov is a fictional character whose name Shopov adopted as his own pseudonym.

Europe is bursting with bizarre, thought-provoking and striking contemporary art – you just have to look in the right places.

Gavazov is a name with which I am familiar, although I have to admit I know, or knew, very little about, until now. An excellent piece of writing and thank for the fascinating journey. My only criticism would be more please! Still, you’ve left us with an interesting list of sources to delve into. Thank you.

I’m seeing a desire here among Bulgarian artists to be part of the Western, modern artistic community by emulating them and innovating the style based on these principles.

They lack the platform to introduce local artists to a wider audience.

The Eastern and Central European art industry suffers from the stigma of Communism even after over 20 years since its fall.

Eastern European arts have not enjoyed their time in the spotlights, and the social, economic and political context in the region can provide a part of the explanation.

I visited Sofia’s National Art Gallery on Battenberg Square, and saw some amazing Bulgarian art and great selection of European photography.

Is it bad if I say that I love print propaganda by Soviet Russia’s avant-garde artists and writers?

The Eastern and Central European art industry suffers from the stigma of Communism even after over 20 years since its fall.

Creating and promoting contemporary art often comes hand in hand with mastering the art of survival.

This article and the content is an evidence that a lot of Eastern European art is becoming very attractive for Western Europeans.

There is still a debilitating shortage of public money available to artists in the EU.

Wonderful article!

I am so glad that Mel Brimfield is a part of this article!

Are you yourself Bulgarian?

Yes 🙂

An interesting article about something I know nothing about. A nice job linking Eastern European art to its past under Soviet rule.

i love this post

Thank you for such an interesting article