The Secret History: A Novel with Staying Power

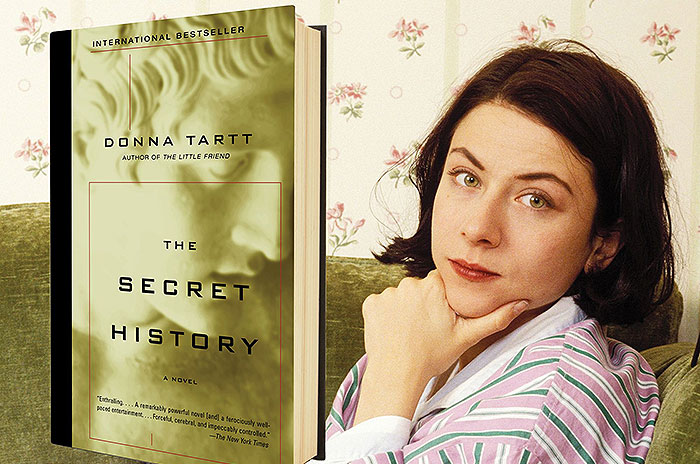

When Donna Tartt published her debut novel The Secret History 1 in 1992, it became an instant classic. With more than 5 million copies of the novel sold worldwide, and it being translated into 24 languages, Tartt was transformed into something of a literary icon. Possessing a unique and timeless quality, many have read this cult classic. More than this though, The Secret History has amassed a devoted following which is still thriving almost thirty years after its publication.

The author describes The Secret History, not as a whodunit, but as a ‘whydunit.’ Set in an idyllic liberal arts college in Vermont in the 1980s, the novel focuses on a group of mysterious and elegant Classics students. However, not everything is as it seems in this peaceful corner of New England. Haunting this prestigious clique of students is the murder of their peer, Bunny. The novel’s fame suggests that The Secret History is more than just a captivating murder mystery.

From the way the story is told to the story itself, Tartt’s The Secret History has enormous staying power. On the surface, the enthralling plot, picturesque setting, and enchanting characters keep the reader invested. But the novel’s staying power comes from more than just this. The way this novel has been constructed carries as much importance as its content. From the deliberate choice of narrative style to the author’s subtle sense of humour, this novel leaves readers with a lasting emotional impression.

Warning: this article does contain major spoilers.

An Unconventional ‘Whydunit’

In identifying the reasons for The Secret History‘s popularity, it would be remiss to not include the novel’s exceptional and well-paced plot.

The first sentence of the novel’s prologue introduces the death of Bunny, a character we are yet to meet. The narrator, who we are also yet to meet, admits to being “partially responsible” for Bunny’s death. We also learn that this death was premeditated murder. Thus, within the first few pages we learn the details of what should be the complication in the plot. That is with the exclusion of one important fact: why did they do it? For this reason, readers spend the first half of the book wondering, what happened? as the narrator slowly retells every event that led up to that gruesome occasion. The novel is truly a ‘whydunit’, a play on the famous term ‘whodunit’ ascribed to murder mysteries in which the killer remains a secret until the conclusion.

After this punchy prologue, the story builds with immense slowness. We meet our narrator, Richard Papen, and all of his friends slowly thereafter. Together, they study Ancient Greek under the impassioned tutelage of Julian Morrow. They discuss what seem to be abstract ideas; everything from striking beauty to the ability to lose all control. As Richard grows closer to this group of scholars, we do too. Just like the narrator, we see everything good about these people. Consequently, as we read, we cannot fathom how this intelligent and elegant group of friends end up where the prologue says they end up.

Until, that is, one event that changes everything. During Richard’s first Greek lesson we learn, as the students do, about the Greek ritual known as a Bacchanal. Having a grasp of Ancient Greek history is not crucial — it is explained simply enough. This ritual causes the participants to lose control of their actions entirely. During this ritual, they may even see the God Bacchus (or Dionysus in Greek). Henry Winter, the unspoken leader of this group, decides that he wants to participate in a Bacchanal ritual.

Richard, not yet close enough to the group to be involved, learns of this after the fact. The rest of the group partake in the traditional preparations, fasting and drinking copious amounts of alcohol. At the last minute, they make the decision to exclude Bunny as he refuses to take it seriously.

The ritual worked. But, it results in the group killing an innocent farmer in a gruesome manner. It is here that everything changes. Though eager to keep this accident covered up, Bunny finds out. Wracked with guilt, his mental health begins to deteriorate and he grows ever closer to telling someone about his friends’ transgression. By this point, Richard gets dragged into the drama and it is here that the group decide that they must get rid of Bunny.

This marks the end of book one. Book two contains, arguably, less excitement. The guilt-stricken friends participate in the ten day police search for Bunny, believed simply to be missing. While the local Hampden police are oblivious, the FBI come close to discovering the truth. The recovery of Bunny’s body prevents this, and the funeral ensues.

The novel reaches its conclusion, then, with this group of friends having unravelled completely. The friends are no longer friends, one ends up an alcoholic, charged with drunk driving, one commits suicide whilst another attempts to do the same. Richard is the only one who graduates from college. From that one pivotal and murderous moment of their young lives, they are destined to live with permanent guilt and sadness.

The Secret History builds slowly and adds the right amount of excitement. Readers are captivated by this unusual sequence of events — the tragedy and sadness of it all is striking. From the prologue’s first sentence, readers are hooked to find out just what happened. But to attribute the novel’s staying power to just this would do it a disservice. The novel’s appeal comes from far more than its plot.

The Campus Novel

The campus novel genre has its origins in the 1950s. This genre is usually characterised by its setting; novels of this category are set in and around a university campus. Often, these novels will critique or mock the perceived pretentiousness of this setting. The coming-of-age story usually works in conjunction with the campus novel.

Canadian writer, Randy Boyagoda, wrote on the appeal of the campus novel, explaining that:

“The campus novel is a genre that makes a distinct promise to readers. It offers a hothouse evocation of highly educated individuals in close orbit and in frequent collision, who uniquely combine intense personal interests with abstruse professional pursuits – all while surrounded by young people making uneven transitions to autonomous adult living. Often, they do so with the threat of personal and institutional breakdown and bankruptcy in the air.”

Randy Boyagoda, Why Campus Novels Matter, University Affairs.

As preferred genre is subjective, it would be misguided to attribute too much of the novel’s popularity solely to its genre. That being said, the campus novel does have a certain appeal. As The Secret History demonstrates, this type of novel allows room for a high degree of acceptable snobbery and eccentricity. It takes a romanticised institution, the college campus, and makes it accessible to any person who might want to experience it. It creates the perfect environment for adults without responsibilities to run amok. For part of Tartt’s audience, this would certainly prove an important factor in their enjoyment of the novel.

The Picturesque

“Does such a thing as ‘the fatal flaw,’ that showy dark crack running down the middle of a life, exist outside literature? I used to think it didn’t. Now I think it does. And I think mine is this: a morbid longing for the picturesque at all costs.”

These opening lines of the novel’s first chapter eloquently sum up both the focus of the novel and one reason why the novel is so adored. That word in particular, picturesque, is the pillar upon which this novel rests. The narrator is in pursuit of it; when he finds it, we get to enjoy it alongside him.

A Brief Lesson in Semantics

The Oxford English Dictionary offers several definitions of the word ‘picturesque.’ It details the various ways in which this particular word has been used throughout history.

The way in which the contemporary reader likely understands the word ‘picturesque’ has been in use since the early 1700s. Derived from the word ‘picture’ – the word denotes that which has the qualities of a picture. Usually given to scenery, ‘picturesque’ is used to describe that which is beautiful and striking in appearance. This seems the kind of picturesqueness that our narrator, Richard, pursues.

More obscure, the word ‘picturesque’ is also used in relation to language and narrative. It is used to describe stories, narratives, or accounts which are very obviously graphic, vivid, and striking. The rich description that appears on nearly every page of The Secret History demonstrates that, with her unique story-telling, Tartt is creating a picturesque narrative. This, it seems, is the kind of picturesqueness that we as readers are drawn to.

Both definitions of this peculiar word are working in concert to create the truly timeless text that is The Secret History. Tartt’s world and character building creates an atmosphere most romantic and enchanting.

A Romantic Setting

From the moment the narrator steps off the bus and onto the grounds of Hampden College, readers are given a sense of the picturesque. Vermont, over four thousand kilometres away from Richard’s home in Plano, California, is described “like a country from a dream.” A sun rising over mountains, birches, and thriving meadows greet the narrator.

Bennington College in Vermont, the gardens of which are pictured below, is where Tartt was studying when she began writing The Secret History. This school, like the fictitious Hampden College, is a liberal arts institute. It is believed that in creating Hampden, Tartt drew inspiration from her own campus. It appears that Richard, in his pursuit of the picturesque, has certainly found it in this setting.

Tartt manages to make even the least wonderful of buildings, dorm rooms, seem picturesque. Richard explains that what he expected in a dorm room was “cinderblock walls and depressing, yellowish light.” But, to his elation, his accommodation turns out to be one of many “white clapboard houses with green shutters.” His room in particular has “big north-facing windows” and expensive wooden flooring. Hampden College, it seems, is the exact place Richard has been searching for.

Throughout the novel, Tartt emphasises beauty by making other places, or people, seem comparatively less beautiful. Richard seems to view everything as a dichotomy; it is either enchanting and picturesque, or it is not. He either approves wholeheartedly or he disapproves. Demonstrating this idea, the narrator introduces his hometown of Plano, California, on the first page of the first chapter as “a small silicon village.” He associates Plano with “drive-ins, tract homes, waves of heat rising from the blacktop.” Compared to the rich imagery assigned to Hampden, readers are positioned to see this home town as inherently inferior.

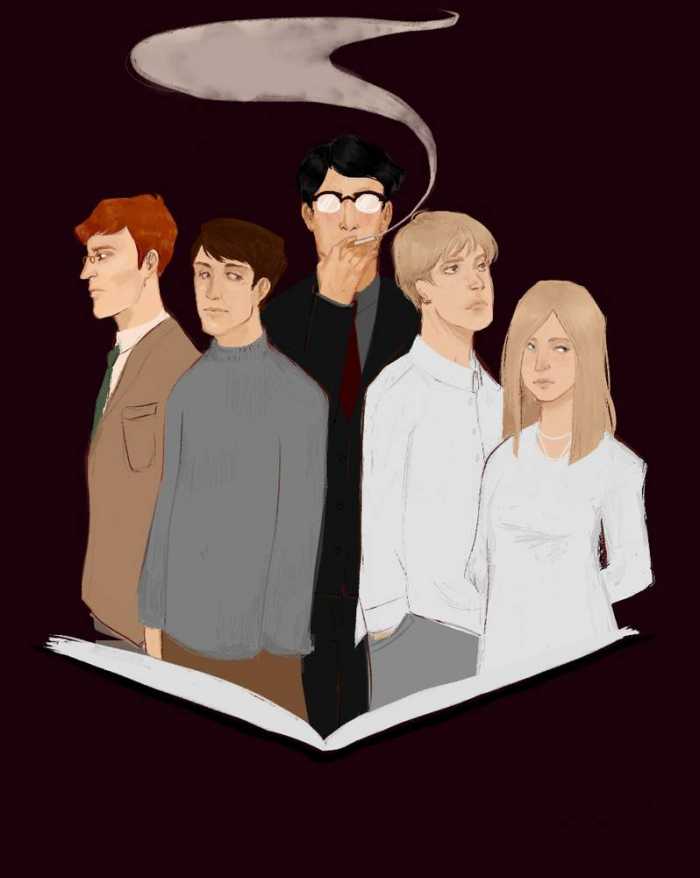

Enchanting Characters

While the picturesque is usually limited to landscapes, the same romantic descriptions can be identified in Tartt’s character building. The key characters are described as infinitely more desirable and dynamic than the novel’s few supporting characters. The best way to understand the enchantment ascribed to these individuals is to read how Tartt has chosen to portray them.

Henry Winter is oddly charming, he has several peculiarities. He wears small, old-fashioned glasses. Over six feet tall, he’s dark haired and a little mysterious. Dressed in English suits and carrying an umbrella, he is said to have walked with the “self-conscious formality of an old ballerina.”

Henry seems to come from equally as mysterious origins. His father is a construction tycoon, yet nobody knows what he really does, and Henry acts as if he does not even know himself. He’s an only child, adored by his “awfully young” mother. Henry’s family is fabulously wealthy, but it is allegedly new money. Tartt portrays Henry as enigmatic from the novel’s outset. Within the first few pages of the novel, the other characters are introduced. However, it is not until the second chapter, over fifty pages later, that Richard, and readers, are introduced to Henry. He is continually positioned just out of reach; he’s a source of intrigue.

Edmund ‘Bunny’ Corcoran lacks some of the mystique that his friends exude. He’s “a sloppy blond boy, rosy-cheeked and gum-chewing,” as well as perpetually cheerful. He wears the same old-fashioned glasses as Henry. Each day, he wears the same tweed jacket, slightly frayed and not quite tailored.

Despite being less alluring than the others, Bunny’s wealth boosts his social standing. He had “an American childhood.” His father was a football star who later became a banker. With four brothers, Bunny grew up in a wealthy suburban home. They had everything that Richard saw as desirable for a childhood; “sailboats and tennis rackets and golden retrievers.” They went on frequent holidays to Cape Cod and they were educated in the best schools.

From left to right, Francis, Richard, Henry, Charles, and Camilla.

Charles and Camilla Macaulay are the only twins on campus. Their faces are clear and epicene, and they both have blonde hair. Hampden is known for its intellectualism and decadence and, as the stereotype goes, students dressed in black and moody attire. The twins, preferring to dress in light colours, stand out. Compared to the “dark sophistication” of the rest of the campus, the twins appear to the narrator as “long-dead celebrants from some forgotten garden party.”

Camilla, being the only woman of this group, instantly grabs the attention and gains the affections of the narrator, more so than the others. Richard describes her as being blisteringly beautiful. So much so that, when her face was illuminated by the sunlight, the narrator says it was “a shock to look at her.”

The twins are orphans, but even this is portrayed as a fortunate upbringing. Camilla and Charles were raised by various grandparents and older relatives. Though their family life is not delved into, they are said to have grown up surrounded by “horses and rivers and sweet-gum trees.”

Francis Abernathy is “the most exotic” of this group. He’s “angular and elegant.” He has bright red hair. His wardrobe is impeccable; he wears beautiful shirts with French cuffs, expensive neckties, and a long coat that billows out behind him as he walks. Despite having perfect vision, he even wears fake pince-nez from time to time.

Francis’ mother was only seventeen when she had him. After his wealthy father ran away, Francis was brought up by his grandparents, with his mother being more of a sister to him. Despite this, his family life is described as “impressive.” He spent summers holidaying in Switzerland, he had English nannies, and attended several private schools. Francis is wealthy, with much of the story taking place at his extravagant home in the country.

To the narrator, a self confessed plain and clumsy man, this elegant and mysterious group of friends seem wholly unapproachable. Tartt is cautious to stress that the narrator, who is meant to be the reader’s equal, has nothing in common with this group of students. Yet, like the reader, Richard is burning with curiosity to know them. Part of the novel’s appeal is the appeal of these characters.

There are undeniable elements of the picturesque within the way these characters are described. Likened to angels or garden party attendees, they are written to be admired, liked, and envied. Tartt emphasises these ideas by making negative contrasts. Richard describes the students outside of this friend group in a rather unflattering fashion. Judy Poovey lives a few doors down from the narrator. He says that “she had wild clothes” and a voice “which rang through the house like the cries of some terrifying tropical bird.” Or of Judy’s friend, Beth, Richard says she had “a rubbery face and an idiotic giggle.” Richard loathes her. Tartt uses these comparisons to ensure readers understand the narrator’s attraction to the Murder Squad.

It is Richard’s longing for the picturesque that gets him in trouble. He learns too late that the decadence and pretentiousness of his friends is merely a facade; perhaps he would have been better off befriending the uncouth Judy. His desire for the picturesque, it seems, really is his fatal flaw.

This idyllic world is where readers wish to be too, though. Just like Richard, we are sucked into this too-good-to-be-true world. The way Tartt is able to make her story-world appear timeless means that, for readers in 1992 and for readers today, this Hampden world is enticing and inspires admiration.

Thoughtful Narration

By making the deliberate choice to have Richard as the narrator, Tartt has created an inherent intimacy about her storytelling. The narrator’s eyes, through which we see, saw these events unfold personally. Instead of choosing an all-knowing omniscient narrator, readers are positioned in close proximity to the narrative.

The reader’s feelings, then, are mirrored by Richard’s. When we first learn of the mysterious friends, we share his curiosity. Richard slowly gets to know his peers. After few failed attempts he is accepted into the inner sanctum of the Greek students. We learn of them at the same pace as Richard does. Thus, the narrator’s elation is once again matched by the reader’s when he gains their acceptance. Richard grows closer to the group, and so, too, do we as readers. Perhaps this is why readers love it. The readership feel like they have been invited into something so remarkable, something only very few are allowed to join. For this reason, the novel’s title is slightly deceiving. By seeing through Richard’s eyes, we learn of the murder plot before everyone else. Indeed this history is a secret. But, thanks to Richard’s narration, it is not a secret to us. We are amongst the fortunate few in the know.

With such a narrow margin of narrative distance, it is easy for the reader to become immersed in the fictional world. It is, indeed, this choice of narration that allows the story to slowly build in the tantalising manner that it does. However, the narrator’s introspection is potentially more important to the novel’s staying power.

An Exercise in Introspection

The story of Hampden College that we read is told by the narrator years after the event. It is set up as just that: a story. It includes all of the bias and selective memory associated with human remembering. From the prologue, the narrator acknowledges that this is a story and, in fact, the only story he can tell. The present day narrator interjects throughout the story. Not as explicit as the famous Jane Eyre line, “Reader, I married him!” But, from time to time, present day Richard will begin a sentence with “this part…is difficult for me to write” or “reading back over this, I feel that…” Narrator introspection proves key to the novel’s progression. Without it, the reader might not understand the choices made by Richard and his friends.

Richard is not foolish. He doesn’t just blindly follow, though on the outside it would certainly seem that way. The reader gains insight into the way Richard thinks. Just after he learns that his friends killed the farmer, he reflects:

“I suppose if I had a moment of doubt at all it was then, as I stood in that cold, eerie stairwell looking back at the apartment…Who were these people? How well did I know them? Could I trust any of them?”

This becomes a major point in the narrator’s life as he further reflects that this was “the one point at which I might have chosen to do something very different from what I actually did.” Statements such as this, and the fact that they are remembered years later, highlight how deeply affected Richard is by what he did. The novel is much deeper than a flippant crime story where the assailants escape happily.

However, the narrator’s reflections upon his mixed feelings for Bunny are the are most poignant. Of all the friends, Bunny is the one whom Richard gets to know first. Richard admits to loving him. After the group make the decision to kill Bunny, just looking at him could spark a “strong pang of affection mixed with regret” in the narrator. But, as a hot-headed and insecure twenty year old, Bunny’s increasingly frequent insults about Richard’s lack of money hurt. No matter how much love was felt, this hurt fuelled the anger that allowed the narrator to feel comfortable with killing him.

The wiser present day Richard recognises that this was wrong. He makes the heartbreaking confession that “I can’t think of much I’d like better than for [Bunny] to step into the room right now.” Even sadder still, the broken man realises that “love doesn’t conquer everything.”

The deeply sad introspection afforded by Tartt’s chosen narrative style is touching. It speaks to feelings of loss, hurt, regret. Feelings that are universal. Each and every reader will resonate with some aspect of Richard’s reflections — though likely not to the same extremes. This is a part of why the novel inspires such devotion, even years later.

Youth: A Snapshot

What Tartt has created by combining each of these factors is an accurate, albeit heavily dramatised, snapshot of what it is like to be on the cusp of both youth and adulthood. Murder and Dionysiac rituals aside, The Secret History captures the essence of what this period of life is like.

Whether you are looking forward to it, currently experiencing it, or looking back upon it nostalgically — this time of life is often pivotal. Tartt, having been at university when writing this novel, was likely very aware of this. This is, perhaps, why it is such an effectual age bracket to write about and, consequently, why The Secret History resonates with so many.

Selecting Richard as the narrator is important, as he demonstrates a desire that many feel when they first reach adulthood: the desire to be someone. He wants to transform from the suburban boy into the scholarly man. As he reaches adulthood he is finally able to reinvent himself. He’s dissatisfied with his reality of being a plain boy from Plano. For this reason, he admits to lying about his home life:

“On leaving home I was able to fabricate a new and far more satisfying history, full of striking, simplistic environmental influences; a colorful past, easily accessible to strangers.”

So enthusiastically embarrassed by his upbringing, it makes sense that Richard would go searching for a picturesque location and exciting people, in the hopes of blending in with them. But it also suggests why he would do anything to keep up appearances. It offers insight into why he acted the way he did, including covering up for his friends’ murder of the farmer.

Henry notices this desperate and insecure behaviour in Richard, and panders to his sense of pride. In a conversation, Henry nudges the narrator closer to the truth about the murder of the farmer. When Richard finally guesses correctly that the group had killed a man, Henry retorts:

“Good for you…you’re just as smart as I thought you were. I knew you’d figure it out, sooner or later, that’s what I’ve told the others all along.”

To the reader, this is received as a disingenuous statement. However, Richard takes this as a kind of approval from his new and exciting friends. His desperation to fit in with these people is complete with this confession, he is forever bound to them. This suggests that it was Richard’s youthful insecurities that influenced his decision to implicate himself in a crime that he had nothing to do with. His lack of life experience clouds his judgement to believe that this friendship is worth more than the preservation of his own innocence.

Another element of youth that Tartt manages to depict aptly is the complexity of relationships, and the weight they are perceived to carry. Again, the text explores the idea that friendship is more important than anything. However, various romantic relationships are also hinted at throughout, before being addressed later on.

Instead of the traditional love triangle, Tartt opts for a significantly messier tangle of relationships. Richard loves Camilla, but Camilla loves Henry who ends up dead. Charles has an incestuous relationship with his sister Camilla and is subsequently jealous of every man she speaks to — this leads to a severe falling out between Henry and Charles. Francis has feelings for Charles, who also may have feelings for Francis, but denies them profusely.

Tartt is clever, though, in that these relationships are not ever the novel’s sole focus. Like in life, they are set in the background. The naivety of the Murder Squad, then, is evident in this dynamic. It is made to seem ridiculous that they have just caused the death of two innocent people, but are still preoccupied with unrequited love and jealousy. But this proves accurate of life, though again rather dramatised. At a young age, these issues can sometimes seem most important.

Thus, part of the novel’s staying power can be attributed to this snapshot of youth offered by Tartt. She is able to present many of the insecurities that early adulthood harbours. The desire to fit in, the desire to make something of yourself, the desire to fill your life with interesting people. Even the smallest elements of this are likely to resonate with more readers than a novel focusing on a different life stage. Perhaps going hand in hand with the campus novel — this coming-of-age element to The Secret History is important to the novel’s popularity.

Tone: A Juxtaposition

Within her novel, Tartt has mixed a distinct sense of melancholy with subtle levity to create a tone that readers enjoy. This juxtaposition, sadness with humour, leaves a lasting emotional impression.

The Secret History is unmistakably sad. The novel does not conclude with the characters living happily-ever-after because they got away with the perfect crime. Instead, each member of the Murder Squad is left irreparably damaged by their actions. Richard’s narration gives readers a sense of the inner thoughts plaguing these students. After Bunny is murdered, and Richard returns to his dorm room, he reflects:

“It seemed as if I was waiting for something, I wasn’t sure what, something that would lift the tension and make me feel better, though I could imagine no possible event, in past, present, or future, that would have either effect.”

He is deeply haunted by his actions. Perhaps readers should not sympathise with a murderer. However, comments like this suggest that maybe these were good people who made a genuine mistake.

The narrator who did everything in his power to be accepted by the mysterious group that he admires realises too late that he should not have. He had what he wanted, he was in the group. But, after everything that happened, Richard angrily remarks, “I was stuck with them, with all of them, for good.” There is no happy ending for Richard — he got what he thought he wanted, but he was still deeply unhappy. It is with the inclusion of these small details that Tartt has created a tone that has an impact on readers.

However, sprinkled throughout the melancholic novel is the author’s subtle and irreverent sense of humour. Not least is Tartt’s frequent use of witty one-line jokes. She uses these passing jokes to diffuse tense situations. Just after Henry and Francis finish telling Richard about the murder of the farmer, Richard realises, “music from a neighbor’s stereo was filtering through the walls. The Grateful Dead. Good Lord.” Despite the horrible news that readers just learned, they cannot help but be amused by this coincidence.

Tartt’s frequent use of irony is also effectual. One example being when Richard explains what he dislikes about true crime novels. He says that “at the points of greatest suspense…it would suddenly…switch to some unrelated matter.” The irony in this, however, is that this reflection is placed in the middle of the narrator’s explanation of Bunny’s death. Right when the novel is most suspenseful, it cuts away.

Arguably, the most disconcertingly humorous event in the book occurs during Bunny’s funeral. This event combines deep sadness with Tartt’s subtle humour. The five people who are responsible for the death of Bunny are morally obligated to attend his funeral. They are also compelled to help out and bolster Bunny’s family in their time of need. The narrator describes this as a cruel and unusual punishment:

“It was one of the worst nights of my life…the hours passed in a dreadful streaky blur of relatives, neighbors, crying children, covered dishes, blocked driveways, ringing telephones, bright lights, strange faces, awkward conversations. Some swinish, hard-faced man trapped me in a corner for hours, boasting about bass tournaments.”

The hyperbolic way that the narrator describes the evening conveys a distinct sense of the uncomfortable. It seems that the Murder Squad are being punished for their actions. Wracked with guilt and the paranoia of potentially being caught, this socially awkward situation seems infinitely worse for them (and infinitely more amusing for readers). Instances such as this pop up throughout the narrative.

Readers should be sad about the events transpiring, but they are laughing — this is part of The Secret History‘s appeal. Mixing deeply troubling topics with a flippant sense of humour is a significant part of why readers are so drawn to this novel. The story itself is humbling; the students don’t get to live happily. Their youthful transgressions have severe consequences. But Tartt refuses to be a downer. Her humour adds the lightness needed in this dark tale. The Secret History holds significant staying power, and its playfully melancholic tone can be attributed to this.

After twenty-eight years since initial publication, The Secret History is still devoured and adored by readers. Young, old, academics, non-academics. It is almost a rite-of-passage to read Tartt’s novel at least once. Whether for the reasons listed above, or the product of other factors, Tartt’s novel has an undeniable staying power. A dark and funny campus novel, both beautiful and tragic, this mystery has found a place in the hearts, and on the bookshelves, of many.

Despite its positive reception overall, a point in which the novel has been criticised is its alleged glorification of beauty over substance and praising of the superficial. As one of Tartt’s characters rightfully expresses:

“There is nothing wrong with the love of Beauty. But Beauty — unless she is wed to something more meaningful — is always superficial.”

However, The Secret History demonstrates that despite its spotlight on the picturesque and beautiful, superficial, it is not. Tartt has filled her narrative with ample emotional complexity. For this debut novel of a then-unknown author to find instant and long-lasting fame suggests that it remains a valuable addition to the literary scene.

Works Cited

- Tartt, Donna. The Secret History. Melbourne: Penguin Group (Australia). 2008. Print. ↩

What do you think? Leave a comment.

I read this during my last year at secondary school and absolutely loved it. It’s one of those books that I never wanted to end because I didn’t want to say goodbye to the characters, they seemed so real to me. I subsequently went on to study Classics at uni so points 2, 5 and 9 really resonate with me. I go back to it every few years and each time brings new readings. I accept that not everyone will like it but for me it is the best book I have ever read. Fully agree with all the points in the article as well.

I found that it was a book I raced through on the first read, so taking my time on the second read definitely let me get more out of it. It’s a book to be read more than once in my opinion!

Decent book, but I just didn’t like any of the characters. Maybe that was the author’s intention, but I find it hard to really buy in to a story with no sympathetic characters.

I can understand that! I personally don’t mind that all of the characters are pretty awful people, but I get how for others it can be off-putting. It reminded me of The Great Gatsby in that way though, none of the characters in that book are very likeable either.

Donna Tartt … the Terry Malick of letters.

I read it at the right time: I had just started a postgrad degree at Cambridge, and loved it loved it loved it. Elitism, humor and racy plot at a time academia still seemed desirable and mysterious. Reread a few years later, and yes the strings were showing a bit. Not great literature perhaps, but still an unsurpassable first novel.

The Secret History was a quintessential first novel… brilliant in spots and places, it lured me in and kept me reading fast, but it utterly fell apart 2/3 of the way through. The last third simply doesn’t make sense. In fact, it was the first of an avalanche of novels for me where I found myself asking where the editor was. I can’t count the number of modern novels I’ve read that break out of the gates at a trot, get winded at the mid-point, and flat-out collapse in the home stretch. The Secret History was riding the allure of the macabre, and none of the characters rose above the crime the students commit in the opening pages.

For my taste (and it should be clear that any critique of a novel is just an opinion) The Little Friend was an incomparably better novel because Tartt learned to pace herself, and, if anything, the novel kept opening up and getting better. The darkness at the heart of it was much subtler and hence more believable and compelling. But it was here that she allowed character to drive narrative…not the other way around.

I so know what you mean about modern novels. The more I enjoy the early stages of them, the more I dread the deflation of a waning middle and a saggy ending. The Secret History certainly has the latter. I think Sadie Jones’ The Outcast’ is a wonderful exception – it keeps up its harrowing intensity well, and I wept at the climactic resolution. The Poisonwood Bible doesn’t let you down either.

Know that exact sense of dread you’re talking about, and that’s why I call for more oversight. Unfortunately, cutbacks have profoundly effected this field; my husband is a writer and a friend is a highly regarded writer of what I call the “quiet” kind (most wouldn’t recognize his name, though he’s had glowing reviews in the NYT’s Book Review for each novel) and they’e both decried the death of the editor. Michael has told us that unlike the golden era of Maxwell Perkins (Fitzgerald’s, Wolfe’s, and Hemingway’s editor)virtually no editing takes place anymore. Forget the true artistry of the profession (the suggestions for major changes, cutting, adding, rearranging, pointing out inconsistencies, explaining why something doesn’t work, etc.) at far too many publishing houses they barely check for typos and spelling and grammatical errors. In fact, several houses now make the writer promote his or her own book, and pay for someone to do a line-by-line edit. Houses also keep dropping editors, so even if a writer had the good fortune to find one dedicated to the craft, he or she may leave just as the process is unfolding and the writer is left in limbo; to meet a publication deadline, the rest of the text just gets left as is.

I can’t remember which dreadful thing it was in, but a few years ago I was reading a novel where a character was quoting from “Ode on a Grecian Urn.” It was credited to Shelley (and it was not the character making a mistake; it was the writer’s unwitting error). It’s that egregious.

I will look for The Outcast because if you put it in the same class as The Poisonwood Bible, it must be good. I’m glad you mentioned Kingsolver because she is a writer with a keen vision, steady hand, and perfect pace. She exists in the zone between popular fiction and excellent fiction. I’ve taught many of her novels over the years, including The Poisonwood Bible, and each time my appreciation for her craft deepens.

I have to agree that the first half of the novel is definitely more enjoyable. I don’t think I would say it fell apart, though of course that is just an opinion. But I did enjoy getting to see the characters face the consequences of their actions, I thought that was a really interesting angle to pursue. They didn’t just get away with it, nor were they simply caught by police.

Glad the article made the lineup, and so happy to have helped in the revisions.

It’s great to see this article up! Your article provided me with a good introduction to a book I have never read (but am now intrigued to). I especially loved your final remarks about the superficiality vs. substance debate in regard to this book. It reminded me so much of something Oscar Wilde might say in defense of “beauty for beauty’s sake” (with plenty of potential meaning tucked away inside anyway).

Thank you! I’m glad you enjoyed my article. The Secret History is a lengthy read, but one that I would definitely recommend.

A good essay, interesting to read.

Blasting analysis. That opening with its ‘..this is the only story I’ll ever tell..’ (paraphrased so misquoted by me, I’m sure) gets me every time. Full of melancholy and regret and perhaps even a Great American Novel as well as a fantastic debut.

What struck me in a positive way, and I haven’t seen anyone else mention it, is that it seems like a rewrite of Lord of the Flies, only the isolation that distorts the young people’s morality is intellectual, not physical.

Bunny = Piggy; surely the similarity of names was no accident.

Nice observation re: lord of the flies. I also find the opening peculiarly touching. I often just take it down from the shelf to read those lines.

Downstream there are those who bemoan the elitism and lack of emotion but I found it a novel full of emotion and universal themes. Yes it has a surface layer of elitism and intellectual posturing but the real tragedy at the heart of it is the impermanence of youth and idealism.

What gets me every time is the perfect conjuring up of the time when your friends are everything and your little group is at the centre of the world and the inevitable heartbreak as that slips away.

I always get a little emotional at the line in Stephen King’s ‘The Body’ where he says (badly paraphrased by me also) ‘I’ve never had friends like those I had when I was 12, Jesus, does anyone?’. The part in The Secret History where Richard begins to hope they can stay in their little bubble of friendship forever and no-one will ‘get married, have kids, move away for work or any of the other treacherous things friends do after college’ hits me just as hard.

Whether you are in working class 50’s America or in an elite New Hampshire college that yearning for a certain moment in time when everything was possible is just as keenly felt.

I had never considered this connection before, but it really does make a lot of sense. Thank you for leaving this comment, it’s given me an entirely new way to look at this text.

I came to The Secret History late – I think I was 29 when I read it – and I found it to be tremendously bloated. I can see why people are so smitten with it, though – it flatters the reader from the outset with ‘confidences’, like a clever club you know you have the clever clogs to get into.

Some of the scenes resonate – the bacchanalian parties, the descriptions of beautiful locations – but much of the pontification on character could have been achieved with clever plotting. Tartt’s major failing is that she cannot simply ‘show’ sometimes – she has to ‘tell’, meaning she can exhibit her skills in writing, specifically in the way she describes and in the way she can incorporate philosophy into her work (along with a huge amount of information – I was very impressed with how intelligent and well-read the author must be; shouldn’t I be thinking that about the character, or characters?).

Although the protagonist in the book is learning to be a cynic, and I am definitely a cynic, I read this and longed to be younger, or I wanted to not understand all of the references. I think to really fall in love with this book, elements of the plotting or the characters or the setting have to be completely new to you, to distract from how unnecessarily long it is.

“it flatters the reader from the outset with ‘confidences’, like a clever club you know you have the clever clogs to get into.”

That’s exactly the psychological trick played upon the vulnerable narrator – they flatter him and set him up to take the blame, or even to die. His moment of realisation is absolutely blood-curdling.

This book is simply awful. I read it years ago and it sticks in my mind as being one of the most pretentious, self-satisfied, smug, aren’t-I-jolly-clever novels I have ever had the misfortune to struggle through in order to reach the anti-climactic and so-bloody-what end. It’s like spending an interminable evening in the company of the most tediously over-educated, pretentious, immature bores to ever make it into a junior common room,

I’m still amazed it hasn’t been made into a film. Seems ripe for movie treatment.

Several have tried. Gwyneth Paltrow was attached at one point (she’d have been perfect as Camilla) but for some reason it’s never been adapted.

It would be awful if they tried to update it though. It’s very much a book of its time – pre mobiles and internet and the tech revolution. One of the main draws of the book is the sense of isolation and being cut off from the outside world.

That surprises me too!! But I wonder who they would cast in each role?

Loved this and read it while at Uni, so the timing felt perfect. Poor Bunny and his ludicrous essay – that made me laugh so hard I cried.

That’s why I enjoyed this book so much. It’s genuinely funny!

I was lucky enough to hear Donna speak to a small group in Oxford in 2000 or thereabouts, before The Little Friend appeared, when it was assumed she was stuck getting past The Secret History. She spoke at good length about her writing process (long form, by hand) and her sources of inspiration.

I remember her describing how, as a child, she went through times of intense boredom, staring at the floorboards of her house and the nails driven into them, noticing their variations and peculiarities. It was, she said, the kind of precious boredom that feeds the imagination.

What a novel. Still my fave repeat read.

I wish we’d talked about Donna Tartt’s eccentric career as an audiobook narrator of other people’s audiobooks!

I had no idea she narrated audiobooks!

Her audiobook reading of Charles Portis’s True Grit is really good. There is a Yt clip of her reading her essay about the novel which came with the audiobook.

It’s a long time since I read The Secret History but I thought very badly of it. It seemed that we were supposed to take seriously the protagonists’ own view of themselves as brilliant, geniuses etc. It seemed that Tart intended the art of the book to be consist in the confrontation of these brilliant people who are also privileged, snobbish, amoral etc with the consequences of their actions, consequences that their brilliance will prove, painfully, ‘tragically’, to be no match for. That is a very high dramatic ambition; if it works, you pull off a masterpiece; if it fails, you fall flat on your face.

I though it was the latter. I could not take seriously the author’s presentation of the characters as having exceptional minds. It was all the ‘intellect’ etc as it might be viewed by someone who has internalized a cliché. It all seemed to depend on very trite, faux- Nietzschean received notions of what intellectuals are and the kind of thing that ‘intellectuals’ talk about and the kind of amoral plans ‘intellectuals’ hatched. The kind of thing that could work for Hitchcock with ‘Rope’ but not in a medium of discourse like the novel of ideas, even if it was also intended to be a suspense fiction.

And none of this was intended, I thought: we weren’t supposed to read this and think: cliché. We were meant to take it all seriously.

Yeah, but maybe I got it all wrong, missed something completely.

The Secret History is one of the greatest books ever based on Attc Greek Tragedy.

Thank you for writing this. This has been an absolute favourite of mine for so very long, one of the few books that I have read across decades and found that it has lost nothing to a re-read. Even knowing the answer to the situation does not diminish the read.

I could not agree more! When I read it the second time, especially seeing as it is such a long read, I expected to find less enjoyment in it. This was not the case, though, as I found it just as captivating.

It’s an interesting book but frustrating, as you never really find out what actually happened, or why.

What didn’t you follow? I thought it was all pretty clear.

I didn’t like it much at all. Thought it was clever, but shallow and empty of real emotion and feeling. Bit like your average college student, I suppose.

I agree with Sammy. It’s tediously long, contrived and vastly over-rated.

I was quite young to be reading it (I think that I was 17), but one of the major themes that I took away was about frustrations of the class system and about someone from a poor background looking at a fetid and rotten upper-class, recognising it for what it is, but also wanting to be part of it. I would potentially have a different impression if I read it now.

I definitely think that the age you are and the life experiences you have impact upon how you feel about this book. That’s an astute observation about the protagonist though, I think that his conflicting feelings are certainly evident.

One of my favourite books…

I exchanged a half finished copy of some Robert Luddum spy nonsense for a second hand copy in an Australian cafe in 2005. A great swap! Loved The Little Friend too.

It’s an engaging potboiler, really, a high-end airport novel. It was enjoyable enough but Tattr’s need to show off her erudition really grated, and I found the characters so unengaging, I was only interested in the plot in itself, as a fancy structure – and even that didn’t really pay off. I actually preferred The Little Friend. The Southern cliches were a bit too heavy handed and the story ultimately unsatisfying but at least it had some great moments, some decent writing and a compelling heroine.

I can understand what you mean by her showing off her erudition. When I first read the book, that first Greek lesson seemed ridiculously long and pointless to me. I thought it was just filler. It wasn’t until I read the book again that I realised it was actually a really significant detail.

I’m with you! Although I’d be a bit more generous to The Little Friend. I think it’s wonderful, and so much better than The Secret History.

It’s been a while since I read The Little Friend, but the protagonist is unforgettable and the bit with the rattlesnakes was brilliantly done. I’ve got a phobia of snakes so strong, I usually stop reading when a scene like that comes up, but with this one, I couldn’t.

The end was a little underwhelming, though. Tartt seems to be better at set pieces and atmosphere (the murder, and the evocation of being cold and poor in a bare room, in Secret History are excellent) than she is at the big arcs a novel needs. Perhaps she’d have made a better short story writer.

Am I the only one who prefers The Little Friend to The Secret History? Shout if you’re with me! Or perhaps just reply below …

I have never actually read The Little Friend, but many seem to recommend it so I definitely want to now!

I haven’t read The Little Friend because of the general ill feeling toward the book. I saw there was a copy in my local second hand shop yesterday. Fingers crossed it’s there tomorrow….

They did have it! The Little Friend for 50p. Bargain.

I haven’t read The Secret History, only The Little Friend. There was lots to admire in that from a writerly point of view, but did it really take her 7 years to construct such a tonic-free ending? Maybe it did: maybe she arranged things that way specially out of pure malice to the reader. Because the other thing that forcibly struck me about the book was its sheer inhuman callousness. It is chock-full of pain and acts of casual viciousness and I came away with no feeling at all that Tartt gave f*ck 1 about any of her characters. Scary really. I wouldn’t feel quite easy in my skin living next door to her.

The Secret History was an atmospheric book I totally immersed myself in.

I agree! It is definitely an immersive novel, you can’t help but get sucked into the story world.

I didn’t really get what the fuss was about. I thought it was trying to hard to be clever, and I didn’t much care whether any of the characters lived or died. Ah well, horses for courses.

The Secret History is one of the most powerful, original, haunting and poetic novels of the 20th century, a subtle and deeply moral thriller – I envy anyone who has not yet read it.

A reason to love this book could be its strong sense of place. I haven’t read it in years but I can still vividly picture that Vermont college town as a cold winter comes in. It’s not a ‘cinematic’ book, but the setting is perfect.

Memories…

The way she describes the campus makes you (or at least makes me) want to be there!

I’ve read The Secret History twice, and it is a wonderful first novel.

‘The Secret History’ is probably destined to become a classic of its genre.

I think you might be right!

I liked the summation and analysis of Secret History. It’s something that I wasn’t aware of before but does seem to have a psychological depth. I also like how the article turned out. Good job!

Many people see campus novels as a slice of life genre and not very interesting. I personally like those knds of books, this book has been a book I’ve been meaning to read for a while now and I really like murder mystery books so it really combines the two

Hi Samantha,

Interesting analysis of the techniques and features that sustain this book’s popularity. I’ve only read it recently after numerous recommendations and was captivated by the many highlights you feature… Until the ending… I’m interested that you didn’t include the Professor in your cast analysis. He was a malevolent force and critical to the story, I thought. By dismissing him you ignored the fact that he conveniently disappeared when the going got tough. What did you think of how Tartt wrapped up the story after having invested so much time into building this rich world and characters? After travelling so far, I was sorely disappointed.

“Picturesque at all costs.” What a great descriptive phrase. The delusion of what you think life should be and the reality that follows. I remember reading several War novels before I volunteered, thinking/believing I was about to enter some sort of romanticized chapter during the War in Vietnam. I was, but it wasn’t what I thought. My “Campus Life’ came later, but there were no delusions left for me to believe.

this is very well written.

Even though it has been several years since I read The Secret History, this article reminded me of why I originally loved it and still think about it. You nailed how her use of the picturesque and theme of Beauty contrasts with the dark context of the plot and characters and thus enhanced the dangerous delusion of romanticizing things. Additionally, I agree with you in commending the psychological depth of the characters, Donna Tartt is very skilled in her creation of compelling, complex characters which is undoubtedly showcased in this story.

This is brilliant! Agree with so much of what you said. I read this for the first time recently and absolutely loved it – might just be my favourite novel.

This was so much fun to read – thank you!

A classic, apparently, though I found myself unable to like it. The article, I think, focuses a lot on how well-constructed the book was, especially in appealing to readers’ emotions, but I thought quite the opposite. I couldn’t sympathize with any of the characters, and I sure did not find Henry ‘charming’ in the traditional sense.

Henry is very much implied to be a clinical sociopath – unable to sympathize with anyone else, remarkably self-centered, charming and witty to others so that they don’t realize that he doesn’t feel emotions at all. In my opinion, Henry was the reason any of this book ever happened, because he knew how to attract people and all of the people he attracted, while wealthy to a certain degree, were not quite as well off as they appeared. The article did mention that Richard was chasing the picturesque, but undoubtedly, the rest of them (except for Bunny) were too.

I agree with Decypher above as well, in that the professor was undoubtedly the moving force behind the story, even more so than Henry, probably because he inspired Henry. If I recall correctly, it was the professor who first put the idea of killing someone into Henry’s mind, and Henry who decided to act upon it. But I don’t remember enough about the book to say for sure.

Overall, not as quite a deep or thorough analysis as I was expecting/wanted to read, but an interesting perspective nonetheless.

I finished The Secret History over a period of three days. Once you have entered Tartt’s world, you never wish to leave. Her style of writing, and the feelings it invokes, are rarely captured by modern writers. Tartt is able to made the reader feel as if they were truly a member of this inner circle, in a way that blurs the lines of morality. You cannot help but sympathize with the actions of Richard and his friends, to wish for their redemption despite what they have done.

This book was amazing. Certain parts of it felt a bit too slow, but after finishing it, I was so glad I picked up the book in the first place. The characters, plot, and beautiful details in this novel have moved me and made me want to read more Danna Tartt. Now The Goldfinch is next on my list.

Love the article! I really enjoyed The Secret History, I think part of that appeal personally was from growing up reading books filled with adventures and drama and meeting fabulous people who are otherworldly and desiring to have my own experince like that. The Secret History is in some ways a fulfillment of that desire in a matured version. It takes the mundane and romanticizes it, takes the typical drudgery of school and turns it mysterious with enigmatic peers and dramatic secrets. Compared to the reality of the university experience this is exciting. While I can see the novel as taking the pretentious tone a little too far that for me was part of the resonance of the text.