The Legacy of Ramona Quimby

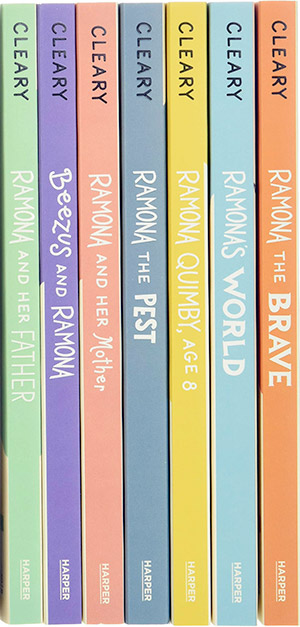

On March 25, 2021, the world lost Beverly Cleary. The prolific and beloved children’s author gave us several memorable characters and series. Readers might recognize names like Henry Huggins, Ellen Tebbits, Ralph S. Mouse, and Otis Spofford. However, perhaps no Cleary character is as memorable and beloved as Ramona Quimby.

Ramona Quimby first appeared as a deuterotagonist to her older sister Beatrice (Beezus) in Beezus and Ramona, first published circa 1955. At the time, Beezus was a sensible nine-year-old, quiet, demure, bookish, and in many ways an ideal girl of her era. In complete contrast, four-year-old Ramona was loud, rowdy, a budding tomboy, and creative in arguably inappropriate ways. Ramona was the kind of girl who would blow into her straw “as hard as she could ‘to see what would happen,'” thus spraying lemonade everywhere. She would wipe finger paint on the cat, take one bite out of every apple in a family-size box and leave the rest, or invite her entire preschool class over without telling anyone.

In the years and decades following Beezus and Ramona, young readers were treated to more Ramona books. Ramona aged and matured somewhat in each book, but her tendency to get into scrapes matured with her. The preschooler who shoved her doll into the oven in a game of Hansel and Gretel became a kindergartner who constantly pulled a classmate’s hair and chased and kissed another on the playground. The kindergartner became a second grader who squeezed out a whole tube of toothpaste to see what would happen–and vent her confusing emotions. The second grader became a third grader who got raw egg in her hair in front of the entire school cafeteria.

Ramona Quimby: A Different Kind of Heroine

In other words, Ramona Quimby was never what BuzzFeed Books contributor Scaachi Koul calls “an ideal child.” “Ramona gave pests like me hope,” Koul writes, adding this character made it okay to be “a Ramona in a world of Susans.” When Ramona first appeared on the children’s literature scene, most of her counterparts were focused on “becoming better children.” Their stories were often built around morals and behavioral improvement. In contrast, Koul tells us Ramona does not “improve” with age. And for Beverly Cleary, that was the entire point of the Ramona books. “I was so annoyed with the books in my childhood because the children always learned to be better children, and in my experience, they didn’t,” Cleary said in a 2014 interview.

Not to say Ramona’s brattier actions are good or imitable, but Cleary and Ramona gave their readers the freedom to experience the ups and downs of childhood. Ramona’s readers loved, and still love, her because as Scaachi Koul puts it, she can be a jerk. She can do unacceptable things and learn better to a point, but she’s allowed to make mistakes. She’s loved and appreciated mistakes and all, if not always understood. Perhaps best of all, Ramona Quimby teaches readers, children and adults alike, how to navigate the world the Ramona way. In other words, perfection and being “better” is not always the ultimate goal, nor the one we need. Sometimes we all need to become Ramonas in a world of Susans. Ramona and her books show us how.

Bend the Rules Without Breaking Them

One of Ramona’s biggest and most relatable struggles is, her personality doesn’t mesh with a lot of the people around her. Again, some of this is down to her original era and her author’s agenda. Ramona could not and would not conform to a demure feminine mold, and Beverly Cleary didn’t want her to. As a result, her shenanigans were funny to readers, but often things they would never dare do. Additionally, Ramona sometimes faced harsh discipline or unfair attitudes for actions that parents and teachers would handle differently today. For instance, Ramona was often chastised or marked down for using incorrect spelling on first- or second-grade level schoolwork. Today’s teachers might warn her, but recognize this tendency as what we now call phonetic spelling. Ramona is sent to her room or sometimes swatted for misbehavior. Many of today’s parents would eschew both punishments. Spanking is considered inappropriately physical, and sending a child to their room is often seen as counterproductive because that’s the same place they sleep and play.

However, Ramona is the furthest thing from a hapless product of her environment. She knows she’s different, and though that frustrates her, she finds ways to embrace it. She’s creative and exuberant, and she makes those traits work for her. When Ramona’s kindergarten teacher Ms. Binney explains an uppercase Q has a tail like a kitty cat, Ramona creates a signature Q with ears, whiskers, and a tail. In first grade, when Ramona loses a shoe on the way to school, she creates a “bunny slipper” with thick layers of paper towels, a stapler, and a hand-drawn pink bunny face. Her unfailing optimism and constant stream of ideas lead her dad to dub her “spunky,” a label Ramona carries with pride. When Ramona finds something she likes or wants to explore, she throws herself into it, such as when she admires firefighters so much, she wears her pajamas under her clothes to school so like them, she can be ready for anything.

Older siblings, parents, and teachers don’t always understand Ramona’s intentions. As with her spelling, they often see Ramona’s creativity, questions, or explorations as purposeful attempts to cause trouble. For instance, in Ramona the Brave, Ramona starts first grade after spending the summer watching construction take place on her house. Said construction involved knocking out a wall to add an extra bedroom. During the year’s first Show and Tell, Ramona announces “some men came and chopped a great big hole in [her] house.” Her friend Howie immediately corrects her, saying he saw himself that the great big hole was not chopped, but pried away with crowbars and covered in plywood. Mrs. Griggs, who is much stricter than Ms. Binney, basically accuses Ramona of fibbing. The whole class follows that lead, and Ramona becomes a first grade laughingstock. She’s embarrassed and indignant, but scolded further when she expresses anger.

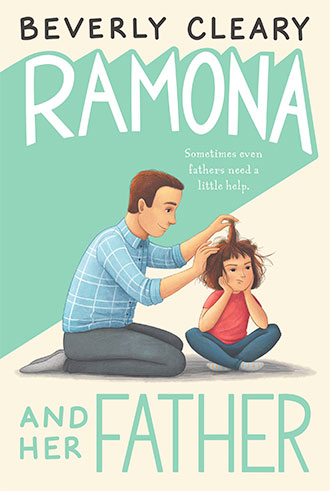

Ramona continues this struggle throughout her books and three more grades. Often, her desire to help others goes wrong, such as when she determines to become a commercial actress and earn a million dollars so her recently unemployed dad doesn’t have to go to a job he hates and her mom won’t worry anymore. (The 2011 film Ramona and Beezus adds the worry the bank will repossess the Quimby house). As a result, Ramona once tries to crown herself like a girl in a commercial playing a princess. Unfortunately, the only crowning material she has handy is a bunch of burrs. Pulling and snipping said burrs from her hair results in many cries of “Yow! Yipe!” from Ramona–and increased worry and frustration from her parents. In other words, Ramona experiences the exact opposite of what she wanted to happen.

In each of her books and the associated film, however, Ramona learns to bend the rules without breaking them, or appearing to break them. She learns how to communicate better with those around her, and in turn, they learn to understand her better. One heartwarming scene in Ramona Quimby, Age 8 shows Ramona drawing a huge mural with Dad, which inspires him to return to college for an art degree. The film adds onto this, showing Dad drawing sketches of Ramona in textbook margins for inspiration. A similar scene in Ramona Forever shows her suggesting her Aunt Bea’s wedding party pick flowers from the yard when the florist can’t deliver on the arrangements. In a later scene, Ramona convinces Beezus both sisters should ditch their uncomfortable bridesmaid shoes and finish the ceremony barefoot.

In all three cases, Ramona either bends the rules of “proper behavior” herself or helps someone else do it. Dads of her era weren’t expected to go back to school, let alone get degrees in fields like visual arts. Proper older sisters did not complain about uncomfortable shoes during formal occasions. In many cases, these expectations still exist, if in different forms.

Ramona, then, reminds us that sometimes, bending the rules–our own or someone else’s–will lead to better outcomes. We’ll express ourselves more freely, abandon the things we’re doing simply to conform, and perhaps find common ground with people who thought we were just trying to fray their nerves. Of course, this takes a bit of finesse. We may still have to cross and dot all our pertinent points to meet reasonable expectations. We may have to live through tough circumstances or watch the tough stuff happen to someone else. The Ramona way, however, reminds us how outside-the-box thinking can make the dull or hard parts of life a bit more fun.

Express, Don’t Explode or Implode

To go along with bending the rules, Ramona teaches us it’s better to express ourselves rather than bottle up our feelings or let them cause destruction. This usually comes across as a cautionary tale, although to Beverly Cleary’s credit, she often handles those with humor, so readers don’t feel preached at. The times when the cautionary tale is more serious, readers can empathize more with Ramona and understand why she makes the choices she does, even if they know those choices are wrong.

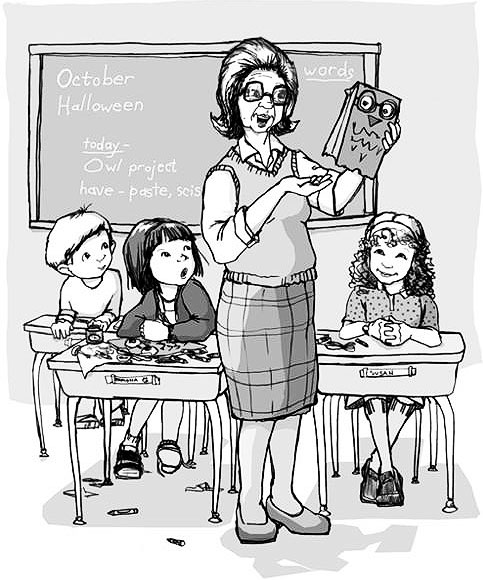

The best example of an empathetic cautionary tale occurs in Ramona the Brave, when Ramona is in first grade. As noted, her teacher is Mrs. Griggs, and their personalities clash. Mrs. Griggs is extremely serious, starting every day with a reminder that “the first grade is not a place to play like kindergarten” and “[first-graders] must learn to be good workers.” Her classroom routine involves endless repetitions of “number combinations and reading circles” presented in a somewhat rote fashion. Mrs. Griggs rarely engages in group activities, arts and crafts, or anything messy or loud. While her teaching style might be comforting to quiet children or those who find comfort in routine, it’s mind-numbing to Ramona. This reaches the point where Mrs. Griggs constantly accuses her of “napping” or not being a good worker when in fact Ramona completes her schoolwork with decent marks and tries hard to pay attention. However, everything boils over during the paper bag owl incident.

Ramona is thrilled when before Halloween, Mrs. Griggs finally lets her class do an art project. They’re assigned to make owls from paper bags, which will then be displayed on Parents’ Night. Ramona throws herself into her owl, creating features like several drawn V’s for realistic feathers and large black spectacles, because owls are supposed to look wise. When Mrs. Griggs gasps in pleasure, Ramona expects she has finally pleased her teacher. But to her horror, Mrs. Griggs praises Susan’s owl in front of the class–an owl that looks like Ramona’s, down to every last feather.

Susan has copied, a high first grade crime. But Ramona knows she can’t prove it didn’t happen the other way around. In fact, she suspects if she speaks up, Mrs. Griggs will think Ramona copied. Failing that, she would almost certainly use one of her favorite phrases, [“Student], nobody likes a tattletale.” Since Ramona already feels Mrs. Griggs doesn’t like her–and Mrs. Griggs has done nothing to dispel this feeling–she can’t risk her class disliking her because she’s a tattletale, too.

Angry, hurt, and confused, Ramona has no idea what to do. In her mind, constructive options will get her in more trouble, but she must do something. So on the way out to recess, she gives in to impulse, grabs up Susan’s owl from the finished line of them, and “scrunches” it until it looks like nothing but “a paper bag scribbled with crayon.” She does the same to her own owl and refuses to make another. Worse than that, Mrs. Griggs forces Ramona to apologize to Susan in front of the whole class. Because of the era, Mr. and Mrs. Quimby express approval of this discipline.

Most readers will recognize it is wrong to wreck another person’s project out of anger, or to wreck your own in an attempt at revenge. Yet the circumstances surrounding the incident, and how Mrs. Griggs chooses to handle it, inspires empathy. In the ensuing chapter, Cleary notes several classmates are extra nice to Ramona after the apology, because they feel Mrs. Griggs was wrong to make her apologize publicly. Many modern readers, and their parents or guardians, might well protest this happened at all, and wonder what they would do in the place of Ramona or a parent. Young readers might suggest ways Ramona could’ve handled the situation differently while maintaining her dignity.

Ramona’s situation inspires empathy based on her anger and impulse. Young readers will recognize those feelings, and may cite times they too have done things they regretted. Some may talk about times they felt they couldn’t go to an adult with their problems or feelings. As for adults, they will probably look at Ramona’s owl incident with empathy and chagrin. This writer remembers rereading the chapter and mentally begging Ramona to speak up, if not to Mrs. Griggs, to a parent or even Beezus. Surely if she had simply explained what happened, she might have avoided humiliation if not discipline, and gotten some help handling the owl situation in a way that didn’t leave her with the short end of the stick.

Most first-graders are not yet in a place to make that connection. But the fact that young readers can with help, and adults can as they reread Ramona the Brave, is inspiring. It reinforces a valuable lesson, too. That is, some adults are still prone to explode and cause some kind of destruction when they’re angry. They may say nasty things they can’t take back, or throw things, or punch walls, or frighten those around them. Some adults still feel they won’t be heard if they approach a bad situation constructively. Maybe they have a Mrs. Griggs in their heads, still insisting, “Nobody likes a tattletale.” However, speaking up and standing up is usually worth the risk if it prevents explosion and the misunderstandings that lead to adult forms of discipline. Speaking up and standing up, more importantly, is always worth it because doing so instills confidence, as well as trust in people who help you do it.

Ramona learns this lesson somewhat in subsequent books, but it takes a while before she learns to consistently manage her emotions. By third grade in Ramona Quimby, Age 8, her explosive temper has mellowed quite a bit. She can acknowledge Susan politely. She also has an easier time with her third grade teacher Mrs. Whaley, who uses humor, projects, and hands-on learning to communicate with her class. Additionally, Ramona likes Mrs. Whaley because she treats her more as a person on the teacher’s level. Mrs. Whaley invites the kids to enjoy DEAR (Drop Everything and Read) time every day. Mrs. Whaley lets the kids interact with fruit flies for science class. She encourages the class to “sell” books for book reports, drawing on creativity. In other words, Mrs. Whaley expects her class to be more grown-up without being pedantic. Being more grown-up is a privilege the class has earned, and it can be fun if handled responsibly.

Unfortunately for Ramona, this leads to an incident of emotional implosion. A big trend for third-graders involves bringing hard-boiled eggs to school in their lunches and, rather than peeling them, rapping or whacking the eggs against their foreheads. Ramona’s new friend Sara is a careful, timid rapper, but our Ramona is a whacker. This would be fine, except the day she asks for an egg in her lunch, Mom accidentally takes one from the raw egg shelf in the fridge. Ramona ends up with egg literally on her face and in her hair. While she’s waiting for the school secretary to wash the egg out, Ramona hears her in a conversation with Mrs. Whaley. “I hear my little show off came in with egg in her hair,” the teacher says amicably. She then chuckles, “What a nuisance.”

Ramona is crushed. A teacher she likes, a teacher who treated her like a responsible person, called her a nuisance. Mrs. Whaley, it seems, thinks what everyone else does about Ramona–she’s an ignorant little kid whose attempts to fit in or be serious are at best funny and at worst inappropriate. Thus, Ramona makes up her mind never to bother Mrs. Whaley or do anything nuisance-like at school. She draws inward, and for a while, it works, until the day of the fruit fly project.

Mrs. Whaley gives each kid a jar of fruit flies to study. The insects are living in oatmeal dyed blue so the kids can see them. Already a bit queasy, Ramona finds the blue oatmeal makes the sensation worse. She considers telling Mrs. Whaley she doesn’t feel well, but that would bother her teacher and make Ramona a nuisance. So she tries to talk herself into feeling better, trying not to move anything, “even a little finger or an eyelash.” But then, “everything in her middle [seems] to go in reverse, and there [is] her breakfast on the floor.”

In Ramona’s mind, she has committed the ultimate “nuisance” infraction, and the most humiliating infraction an elementary schooler can, period. As kids her age are wont to do, Ramona feels isolated, as if she’s the only one who has ever vomited at school. This, coupled with her fear of bothering her teacher, makes it hard to enjoy the little perks of being a sick kid, like having Mom at home to care for her and getting to drink soda, which as both a junk food and an unnecessary expense, isn’t often found in the Quimby house. Not even her classmates’ get-well cards, including a message from Mrs. Whaley, help, because as Beezus says, “They copied them off the blackboard.”

Ramona holds her feelings in so much, their negative impact continues even when she returns to school. She loses her enthusiasm for a creative book report project, is sullen with her parents, and withdraws from Beezus rather than bantering or picking on her. In fact, if it were up to Ramona, she might never have confessed the truth. Rather like her vomit, it comes out unexpectedly and in front of Mrs. Whaley, in that Ramona accuses her, “You called me a nuisance,” to her face. In Ramona’s era, and sometimes in ours, this wouldn’t be kosher behavior. Kids, especially those who aren’t nuisances, don’t eavesdrop on teachers, and if they do, they don’t let on to what they heard.

The good news is, both Ramona and Mrs. Whaley learn a lesson from the incident. Mrs. Whaley apologizes and explains she meant the egg in Ramona’s hair, not Ramona herself, was a nuisance. She also kindly warns Ramona that next time, she should ask what was meant first, even if it means approaching her or another adult with an uncomfortable question. Cleary doesn’t give us Mrs. Whaley’s point of view, but readers can also assume the teacher learned to be more careful with her word choice and tone. In interviews, Beverly Cleary did mention this whole incident was a “softened” version of a time when a teacher actually did call her a name. Knowing Cleary’s attitude toward children and their relationships with adults as they do, older readers can see a connection between what went wrong in Cleary’s story vs. how Mrs. Whaley and Ramona rectified their situation.

Ramona’s egg incident and the rest of Age 8 holds another lesson for adults. Most adults, this writer included, tend to think they’re handling emotions well as long as they aren’t causing grown-up destruction or exploding. But adults who hold their emotions in will implode as Ramona did. Worse, because of their ages, adults will face bigger and farther-reaching consequences related to imploding. Ramona probably made herself sicker than normal with a common stomach flu; adults might get sick with more severe illnesses or have nervous breakdowns. Ramona lost her spark in school; adults might end up burned out and questioned, chastised, or written up at work. Thus, just like for Ramona, adults can learn to approach others with their real feelings. They would do well to find a “Mrs. Whaley” in their lives, such as a trusted family member, clergy, or counselor to help, especially if emotional bottling occurs long-term.

Seek Positive Attention and Outlets

Ramona’s books are so popular in part because of her antics. Kids find her exploits funny, and adults can look back on them with nostalgic chuckles. It’s important to note though, Ramona’s antics don’t translate well to real life. Kids who attempt them might get a laugh or two, but are more likely to get in trouble. As for adults, most will not purposely engage in antics or pranks because as with exploding or imploding, the consequences may be farther-reaching and harder to live down.

Yet, Ramona’s irrepressible imagination and impulses do have something to teach adults, and kids too, about attention. That is, the Ramona series does a non-preachy, humorous job of exploring the difference between positive and negative attention. What’s interesting about this is, every time Ramona does something that garners negative attention, she eventually does something that garners positive attention. They may not balance each other out completely, but the balance does ensure readers keep rooting for Ramona. It also helps readers of all ages understand how to find positive attention, or outlets when such is not available.

One of the first and best examples comes from Ramona the Brave. As noted, Ramona has struggled all year to get along with Mrs. Griggs, in part because of the hole-chopped-in-the-house and owl debacles. In the book’s last chapter, Ramona faces a large, scary dog on her walk to school. The encounter leaves her unhurt, but shaken, as she had to distract the dog to get her lunchbox back, and lost a shoe. To make the situation worse, Ramona has to rush to get to school on time, and nearly misses her opportunity to lead the Pledge of Allegiance, an honor she’s coveted all year.

Not about to let said opportunity slip by, Ramona attempts to lead the Pledge on one foot, her shoeless one tucked behind her ankle. When Mrs. Griggs notices and asks what happened, Ramona expects to be scolded or disciplined yet again. Yet Mrs. Griggs surprises her, and gets a surprise from Ramona, too. The teacher is not concerned about Ramona’s lack of a shoe, but whether or not she’s hurt or upset. Furthermore, when Ramona explains what happens, Mrs. Griggs doesn’t accuse her of exaggerating. Instead, she and Ramona’s classmates are impressed and compliment her bravery. Best of all, Mrs. Griggs loves the slipper Ramona made to replace her shoe. Mrs. Griggs not only praises the work, but notes it’s particularly creative and above Ramona’s age level.

As the book ends, Ramona finally feels like the brave and spunky girl she wants to be. She is not a fibber or an owl copier, or the poor little kid whose classmates had to be “extra nice” to her when she got in trouble. She is instead someone her classmates can admire and respect, and someone who adults can recognize as maturing.

Mom, Dad, and Beezus constantly tell Ramona she should grow up, but don’t tell her how. So like any kid, Ramona learns through trial and error. During Mother, she decides to squeeze out an entire economy-size tube of toothpaste into the sink, just because she has always wanted to do it. Ramona crafts an interesting creation, a toothpaste “cake” complete with swirls and rosettes. But she also wastes toothpaste, a fairly serious infraction since money is tight, and ends up “banished” from the family tube until the used stuff is all gone. And during Father, Ramona not only crowns herself with burrs, but also makes a smart remark to her teacher in an effort to imitate a child in a commercial.

Ramona does try to help. She runs into problems because she’s still too young to understand her “solutions” won’t always translate to the adult world as such. In Father, she joins Beezus in trying to get Dad to quit smoking. Some attempts are innocent and funny, such as when Ramona makes a huge NO SMOKING sign to hang in the house, which reads as NO SMO KING because she ran out of room on the paper. Other efforts, such as hiding her father’s cigarettes, are not nearly as appreciated or taken as innocent. Additionally, Ramona’s frequent efforts to imitate Willa Jean (e.g., calling tomatoes “tommy-toes”) are seen as babyish and annoying, whereas with Willa Jean, they’re cute.

Ramona encounters similar problems during Mother. A great example occurs in Chapter 1, A Present for Willa Jean, when the Kemps come to an after-Christmas brunch at the Quimbys. Knowing she’ll be expected to share her favorite toys–and likely see them destroyed–Ramona decides to give Willa Jean a present. She notes if she gives Willa Jean a present, the adults will dote on her, saying how generous and kind she is to do it, “and so soon after Christmas, too.” Ramona imagines herself in her red turtleneck and green plaid slacks, favorably compared to a Christmas elf.

Drawing on a favorite memory, Ramona decides Willa Jean needs a box of Kleenex. She can pull the sheets out one after the other, as fast as possible, and fling them all over the house as Ramona once did. Ramona knows she’d get in trouble if she did this now, but recalls at Willa Jean’s age, it was great fun. Besides, Willa Jean is so doted on anyway, the adults will probably laugh. Actually, the adults are horrified when Willa Jean figures out what she’s supposed to do with the Kleenex. Her good intentions misconstrued again, Ramona gets a lecture, and spends most of the brunch alone in the kitchen.

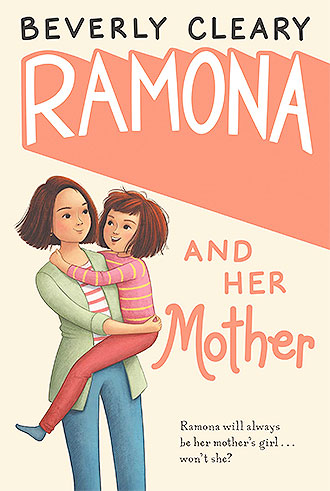

Ramona is never kept down for long, though. She knows she is capable of pleasing adults, so she keeps trying. It’s slow at times, but her efforts pay off. Later on during Mother, Mom and Beezus fight over Beezus’ hair. Beezus is sick of home haircuts and has saved her money to get a professional styling at a beauty school a short commute away. When Mom balks because of the commute and expense, Ramona sides with Beezus, noting she will look “pretty” in the hairstyle she chooses.

Mom agrees to go to the beauty school, but Beezus is matched with an inexperienced stylist. Beezus wails that the ensuing haircut looks like a “cheap wig,” and Ramona privately agrees Beezus looks like, “an unhappy sixth-grade girl with forty-year-old hair.” But where before, Ramona would’ve milked the opportunity to pick on Beezus, this time, she keeps her assessment to herself. Even when Ramona is offered a free cut as compensation, and hers turns out great, she doesn’t lord it over Beezus. Her quiet empathy brings the sisters closer, and lets Mom know Ramona is capable of maturity. By the end of the chapter, Ramona feels like the benevolent pixie for which her hairstyle is named. She’s still on cloud nine from the positive attention her haircut received from other stylists, too. But getting a positive reaction from Mom, and a true sisterly moment with Beezus, meant more.

Similar examples happen in Father. The first is expanded on in the film Ramona and Beezus, when Ramona and Dad combine their artistic talents to draw a mural. In the book, this is simply a rare father-daughter moment. In the film, the mural creation occurs when Dad stays home with Ramona when the latter is sick (the aforementioned vomiting episode). Dad suggests they draw “the longest picture in the world,” and a detailed rendering of Ramona’s school and neighborhood, plus some Oregon landmarks like Mount Hood, results. Ramona and Dad bring the drawing to school, and Ramona’s class and teacher are impressed. In fact, the teacher asks if Dad might be interested in becoming an art teacher at Ramona’s school. In other words, Ramona’s love of art has brought her closer to her dad, helped her straitlaced teacher see her creativity has worth, and possibly helped Dad with his employment situation. Better: Ramona has not had to try impressing adults to do any of this. She’s simply herself, and it pays off.

Another episode not mentioned in the film, but important to Ramona and her Father, puts Ramona’s burgeoning maturity and creativity in the spotlight again. At first, though, it seems like this slice of life will go as badly as Ramona’s present for Willa Jean did. The Quimbys’ church is gearing up for the Christmas pageant, and Ramona’s Sunday school class is tapped to play sheep. Ramona will need a sheep costume, and after seeing the one Howie’s grandma made him, she just knows Mom, with her sewing talent, can replicate it.

In reality: Mrs. Quimby has taken on a lot at work and is too tired to sew. A store-bought costume is out of the question. When she overhears Dad warn Mom, “We don’t want a spoiled brat on our hands,” Ramona nearly reveals she was eavesdropping and breaks down. To even have it suggested she’s a brat, when that’s the last thing she wants to be, is demoralizing.

Ramona does get to be a sheep, along with classmates Howie and Davey. But while the boys have actual costumes, Ramona is consigned to wearing a cotton ball tail and homemade ears, with a set of white pajamas that are faded and too small. They even have pink bunnies all over them, which no self-respecting sheep would ever wear. Ramona feels foolish next to her friends, and less worthy of positive attention next to Beezus, who is playing Mary and didn’t need a costume because the church supplied hers. There is a moment when Ramona slips off to the bathroom and almost starts to cry at the injustice of the whole thing.

The catch is, Ramona isn’t alone. Three older girls are in the bathroom doing their makeup. Ramona sort of recognizes their costumes but questions who they are. “We’re the Three Wise Persons,” one girl says, explaining none of the boys in their age group agreed to play Wise Men. To Ramona’s surprise, the older girl also recognizes right away she’s a sheep–pink bunnies or no. Deciding Ramona needs a black nose, she dabs one on with her mascara wand. Upon seeing it, Howie and Davey decide black noses are a must have for that Christmas’ sheep. Once again, thanks to Ramona, something “traditional” has become more fun. While Beezus as Mary will be praised for her “perfect” portrayal, Ramona will get to be a legitimately cute, fun little sheep. Older readers may also infer that the Three Wise Persons’ empathetic–and wise–response to a little kid who seemed lost and alone may help Ramona connect better with little kids as she gets older.

Keep Your World Wide and Open to Change

Children and adults alike have trouble with change. Early on in her series, it seems Ramona is no different. In Beezus and Ramona, she begs Beezus to read her the same picture book over and over. When Beezus takes her to the library in search of a different book, Ramona finds one, but it’s still about her topic du jour, steam shovels. In Ramona the Pest and Ramona the Brave, Ramona struggles with temporary or long-lasting changes, from a substitute replacing her beloved kindergarten teacher to chocolate chip cookies from the store replacing homemade ones in her lunch because Mom has to work. When Ramona does embrace change, such as a new room to herself, she also battles age-appropriate fears like the dark and an imagined gorilla-like monster.

As Ramona gets older though, she learns to embrace change more and appreciate how much wider her world is becoming. She still experiences angst about some things. In Ramona Forever, for example, she worries that Dad’s new job offer in Eastern Oregon will result in a move, a new school, and other upheaval she can’t handle. And she is crushed and confused when the family cat Picky-Picky dies of old age. Aunt Bea’s impending wedding to Howie’s annoying Uncle Hobart piles even more stress on Ramona’s third-grade shoulders at first.

Yet, within these changes, more than the changes of other books, Ramona finds ways to thrive. She tries to imagine what Eastern Oregon might be like, although all she really knows is, the region has a lot of sheep. When the possibility of a move is brought up in the film, Ramona consoles Beezus, who is also worried, by pointing out they’ll still be together. In both book and film, Ramona comforts Beezus again during Picky-Picky’s funeral scene. “I hope you have nine lives, and maybe tomorrow you’ll wake up as somebody else’s cat,” Ramona says in her eulogy. She then reminds Beezus of some good times with Picky-Picky, such as how much he liked melon rind and how Dad purposely mispronounced his name. It’s a great bonding moment, possibly the best and deepest the girls have across the series. In addition, it’s a painful but touching and age-appropriate way for Ramona to face death, one of the biggest changes and mysteries the world can throw at a kid.

Ramona finds a wider place in the world thanks to Aunt Bea and Uncle Hobart, too. She’s against their relationship at first because it will mean “losing” Aunt Bea, who is also a youngest child and has always understood her. Ramona’s sadness only intensifies when she learns Bea and Hobart will move to Alaska post-wedding. However, she finds ways to be helpful and look on the bright side during wedding preparations in both book and film. For example, in the book, Hobart lets Ramona be responsible for a younger child for the first time in her life, giving her charge of Willa Jean. Ramona takes the responsibility seriously and tries to be amicable with Willa Jean, even if it means reading her every single ice cream flavor on a board of over 30. In the film, we see more of Ramona’s fun and creative side as she touches off a water fight and fun family moment while the Quimbys prepare their house for a showing. In both mediums, Ramona is also the heroine of the wedding–for the wedding party when she finds a missing ring, and for Beezus, when she convinces the latter to go barefoot instead of wearing pinching shoes.

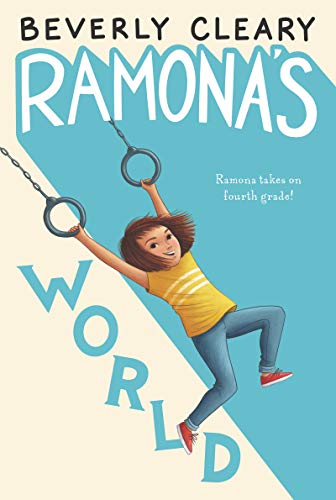

Perhaps Ramona’s biggest triumph in the wider world though, happens in Ramona’s World. Published in the mid-1990s, Ramona’s World is the last book in the series and the most “friendly” toward modern readers. Dated language and spellings are dropped; “cooky” is rendered as “cookie,” and where the Quimby parents were Mother and Father or Mother and Dad before, now they’re Mom and Dad. Ramona’s tomboyish personality is more natural; in fact, she’s not viewed as a tomboy in this book. Rather, she’s a naturally athletic, active girl, and that’s fine. Her pixie haircut, made much of in Ramona and her Mother, is no longer an anomaly, either.

Readers also find out Ramona has grown up a lot between third and fourth grade–or, if we’re using book time, in the decades between her last two books. She struggles with her straitlaced teacher Ms. Meacham, sort of like she used to with Mrs. Griggs. But now Ramona can understand better why certain rules that seem unnecessary to her, such as rules about spelling or following project instructions to the letter, can be good. She maintains a rivalry with Susan Kushner, who is still portrayed as a bit of a goody-two-shoes, especially in the film. Ramona even confesses she still longs to yank Susan’s “boing-boing curls,” but notes she has learned restraint. She sometimes chafes at her relatively new role as the Quimbys’ middle child, but during Ramona’s World, is an attentive sister to baby Roberta. Ramona even notes with some chagrin that Roberta exasperates her just like she once exasperated Beezus.

The final Ramona book sees our heroine branching out with new friends, getting her first female “best friend” in new girl Daisy Kidd and expanding her friendship with Danny, AKA Yard Ape, who was once a “frenemy.” Both friends, as well as the majority of Ramona’s class, is invited to her tenth birthday party, a picnic in the park. Ramona shows some grown-up restraint as far as the invites go, too, when Mom insists on inviting Susan. Susan is the last person Ramona wants to invite, as her superior attitude has been played up during the book. But in a show of almost-ten maturity, she agrees with Mom, albeit reluctantly, that to exclude Susan would be rude.

Ramona’s maturity continues at her party, in what has become a memorable moment for her readers. During the party, Susan is not social and in fact seems genuinely uncomfortable with Daisy, Danny, Howie, and the other kids. She doesn’t show interest in unstructured play or active party games, making the other kids think she’s being a bratty guest. Susan’s greatest offense, however, occurs when she refuses a slice of cake. She takes out an apple and proclaims she won’t eat the cake because it has Ramona’s spit on it from blowing out the candles. Daisy, instantly defensive of her best friend, calls Susan out on her behavior. The other kids agree, showing anger and disdain toward Susan, who ends up crying.

Ramona, and perhaps readers, are surprised when Susan’s actions disturb Ramona. She figures no kid should cry or have to be off by herself at a birthday party, so with Mom’s help, she goes to investigate what’s troubling Susan. It’s here that Ramona and readers learn Susan’s “spit story” was a cover. Her mom sent her to the party with an apple and strict instructions not to eat the cake. Left out of the most important part of a birthday, Susan broke down. She tells Ramona and Mom Quimby that it’s hard “to be perfect all the time,” and confides her mom has always had higher-than-healthy expectations for her. Again, Ramona empathizes, thinking that although her parents haven’t always understood her, they have always loved and never purposely pressured or shamed her. The times that did happen, Mom and Dad were apologetic and understanding.

Ramona realizes Susan’s snottiness is her way of masking insecurity and anxiety, and recognizes this can’t be fun or easy for her. Thus, Ramona does what she can to help, agreeing with Mom that Susan can eat some cake, brush her teeth afterward, and not tell her mother. Ramona even agrees to keep the secret, whereas before she might’ve relished tattling on Susan if she felt justified.

Ramona Quimby: A Treasure of Our Literary World

By the time readers finally leave Ramona in Ramona’s World, they might wish there were more books but know Ramona will be okay. More than okay, she will be well-adjusted, happy, and as creative and spunky as ever, even if she still has to be a “pest” sometimes. Additionally, readers will have found pieces of Ramona in themselves, whether they’re reading along at her age or adults revisiting her adventures.

In fact Ramona, kid though she may be, has plenty to teach readers of every age and every generation. She’s a character we can turn to when we need an outlet, a space to be creative, or a safe way to ask perplexing questions, including those with no answers. She’s a way for us to let our inner children out and maybe confess some “childish” opinions we still have (nobody should be allowed to copy another person’s project, no matter how trivial–and yes, why don’t we wear pajamas to work or school? They’re infinitely more comfortable)! Beverly Cleary may have set out to create a protagonist who was simply realistic and not always “good” or “nice,” and she succeeded. More importantly though, Beverly Cleary created a protagonist whom her readers could relate to, empathize with, and perhaps emulate, no matter their ages.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

I’m re-watching a show I have seen numerous times and there’s an episode where a character dresses up as Ramona Quimby. Because I recently read your article during the editorial process, this is the first time I’ve seen the episode and understood who she was talking about! A useless piece of information, for sure, but it’s what I thought of when I saw your article published.

Also, great writing as always! 🙂

Thank you Beverly Cleary for sharing your wonderful and relatable world and turning countless children into avid readers. And thank you Stephanie for writing the best article I have ever read on her work.

When i was in elementary school I discovered the joys of the Ramona series. As a big sister with a very precocious little sister I identified with Beezus so much. I also felt like Ramona was so on point it was as if Mrs Cleary had a window into my world and she was describing it so accurately. I used to “help” my mom by reading my little sister a bedtime story most nights…usually a Ramona chapter and I often wondered if she felt how I did about the characters and saw herself as Ramona. When my childhood best friend and I had sleepovers (we were shy kids) we would stay up late reading the books and trading each other when finished. I learned later in life that she treasured the books so much she asked her mom for the series for Christmas. I gifted my eldest niece the series when she turned 8 and she still has them at 21. My youngest niece just turned 7. I think I know her next must read series. When my sister was expecting and trying to figure out a great name for my now 7 year old niece, my suggestion was Ramona. My sister did not go with it but my niece would have definitely lived up to the name.

I love that story. Thank you.

Naturally, the Ramona books were the drumbeat of my childhood. The way she was misunderstood and her interior life never seemed to “go” with her exterior life were invaluable touchstones for me as I grew up in a challenging family situation. Emily’s Runaway Imagination and Sister of the Bride were favorites as well, showing us that Ms Cleary’s understanding didn’t begin and end at Glenwood School.

And now, I have a Ramona. An impatient, curious, frenetic, loving, sloppy, full of life and yearning little girl who loves pretty things and named a doll Honey Bunches of Oats. I will read again the Ramona books, not just to comfort myself on the passing of their beloved creator, but to remember what Ramona needs and how I can help her feel loved and understood.

That’s great. 🙂 A doll named Honey Bunches of Oats? Yup, that’s definitely a Ramona move. Love it!

Beverly Cleary gave me a mirror in the character of Ramona. Later, when I taught first grade, I shared her books with my students every year. Best part of every day.

Ramona has always been an inspiration. The best novelists make writing children’s books look easy. It isn’t. I tried to write a YA novel. When Things Go Bang was set in 1959, a coming of age story. However… as I wrote it, the underlying intent began to morph. Darker storylines took the place of the lighter humour originally intended. The village characters changed, some with their own dark intent. In the end I took it to a critique group and was told what I’d suspected: my book, most especially after a complete rewrite, was no longer a YA novel but a dark historical fantasy more suitable for adults. In the meantime, I was reviewing for another author several actual YA novels, brilliantly written in a style that reminded me of Richmal Crompton’s “Just William” books. I wondered how she had done it. She thought it was relatively easy. Sadly, I have reached the conclusion that I really cannot write for children or even teens. Dark themes are irresistible to me.

Good luck with your book!

Absolutely nothing wrong with dark themes for children. Think of all the murders and gruesome bits in fairy tales.

I don’t believe that the William books were ever originally written for children. I never suspected this when I actually was a child, but on trying to read the stories to my young daughter, I realised for the first time how many seriously long words they have in them, and how much time they spend looking over William’s head and sharing a look of wry amusement with the reader.

Great article. Any book that catches the imagination of a child and encourages him or her to rad more is a ‘good’ book’.

As a child it was Enid Blyton that started me on the road to becoming the avid reader that I am to this day. I think it is foolish and counter productive for parents to attempt to censor their child’s reading because they, the parent’s, do not like the author for one reason or the other.

I loved the Ramona books back in the 1970s, a favourite from the library. I still think of Ramona’s kindergarten misconception of the national anthem as ‘Dawnzerlee Light’ and she asked her sister to switch on the ‘dawnzerlee’. So many subtleties there that have stayed with me since primary school. Fabulous that Cleary is celebrated here. Thanks.

Oh yes. The corollory I remember is, Stand beside her and guide her, Through the night with the light from a bulb. Stays with you, doesn’t it?

I moved from the inner suburbs to the country at nine and discovered the joy that was the “mobile library”, a bus with a carpeted floor to lie on so that you could examine the lowest shelves, only cms from the floor, and a step stool to reach the highest, just under the roof. At home we had precious few children’s books – I still own mine and there are about eight – but I read my way back to the picture books and forward to Agatha Christie.

Ramona was a delight to me as a nine year old, and she stood out in a solid diet of British book children with names like “Fatty” and “Fanny” and obsessions with smugglers and fruit cake. I devoured all those books like Enid Blyton’s protagonists devoured their midnight suppers, and I am grateful for them all, but I LOVED Ramona like a real little sister. Thank you Beverley Cleary.

My sister loved them in the late 80s/early 90s. Technically I was a bit old for them, but always used to secretly listen in when she was playing the audiobooks!

A reminder that oodles of Cleary books are available in the children’s section of public libraries. Go for the hunt!

That’s where I met Ramona. Loved the books – still think of Ramona when I write a capital Q).

My kids hated Beezus and Ramona. Without exception. With most ‘kids books’, a couple of them liked some others, a couple didn’t.

I was an avid reader as a child and the book Fifteen made a huge impression on me in preparing me for high school, dating, and the social pressures of growing up.

Oh how I loved Ramona, Beezus and Picky-picky.

Thank you for encouraging a lifetime love of reading, Mrs Cleary.

I enjoyed Beverly Cleary’s books when I was a little girl and maybe even more enjoyed reading them to my own kids. Her writing was honest and clear-eyed, not just about how kids interact with the world but about the lives of everyday families.

Fond memories. Rural primary school, every 3 months a big box of books would arrive, Books that we’d chosen from the puffin book club. An unbelievably exciting day, smelling the pages of our brand new books. The Mouse and the Motorcycle was one of my selections, I can still conjure up the smell of that hotel. Thank you for the magic Beverley.

I remember my sister reading Beverley Cleary as a teenager in Yorkshire, she is now 55. My sister wasn’t an avid reader at the time but ‘15’ opened a world of teen fiction for her.

I loved “15”, read it over and over again when I was 13. I wonder how it would be received by a teenager today

So did I. My copy completely disintegrated.

Ramona was never on my reading table, but growing up, I loved the Roald Dahl books. Had a great dragon poems book too, though I can’t remember what it was called. It’s so important to try and foster a love and appreciation for decent reading material in kids.

“The Dragons Are Singing Tonight”, by Jack Prelutsky? I still love that one and occasionally read it to myself, in my 50’s 🙂

Beverly Cleary influenced a lot of contemporary children’s writers, like Kate DiCamillo. We are living in a golden age of children’s literature, beyond Blyton, Dahl, Ransome and Milne. Check out your local public library, consult an independent children’s bookseller who read and reviews books,

“We are living in a golden age of children’s literature”

I completely disagree, children’s book stores are struggling and reading for children is actively undermined by insanity like Geronimo Stilton.

I loved Ramona and Beezus. Like Beezus, I had a younger sister, who I felt took up more than her fair share of bandwidth. Poor Beezus didn’t even get to have her own name (Beatrice).

Beverly Cleary’s books are warm, funny and authentic. Who couldn’t love Ramona! Fortunately she has some worthy followers. Having spent over 25 years as a children’s librarian in the States, I’d like to suggest a few contemporary American authors who authentically portray childhood friendships and concerns. The following three series are all brilliant, funny, and true to life. Megan Macdonald’s JUDY MOODY series, Sara Pennypacker’s CLEMENTINE books and Annie Barrows with IVY AND BEAN. And don’;t miss Judy Moody’s little brother STINK, who features in a series of his own.

Our elementary school librarian was appropriately named Mrs. Smiley. I still remember the excitement as we would gather on the floor in the library around her and she would exuberantly read to us from one of her favorite authors, Beverly Cleary. She spoke about Ramona as if she was her own grandchild.

I absolutely adored Ramona as a kid who never felt very smart in school and was not an excellent reader at first. But the way Mrs. Cleary wrote was so simple and delightful and created a world and people whose voices I could hear and faces I could see as I read and chuckled along. She started my love of reading as an elementary student and that love eventually turned into studying literature as a major in college and using writing to express myself over my lifetime!

My youngest daughter also had a hard time being still and listening to stories. She hated princess characters and resented books that stereo-typed girls as loving pink and dresses and hating to be dirty, etc. I tried so many books with her! Then, finally remembered Ramona smashing bricks into smithereens with Howie Kemp, smashing an egg on her head, jumping through the hole in her house, and Ribsy the dog going on an adventure all from the dog’s perspective, and I realized I had to try Beverly Cleary with my youngest. Bingo! From the first page, Mrs. Cleary had my messy, creative, pink/princess hating daughter hooked on reading!

I will forever be grateful to Beverly Cleary for caring about children, for loving a good story, for honoring childhood and the little things in life that make it so good.

I remember being in grade school and our teacher brought us to the library to select a book to read. I remember thinking, “there is nothing here for me” but then I discovered Ramona and I fell in love. I became so obsessed with all things Ramona, I felt like she was a friend I would love to have. I read the entire series and loved all of the characters. I just couldn’t get enough. When my girls were old enough I introduced them to the Ramona collection.

I didn’t read Mrs. Cleary’s books until young adulthood, but the Ramona series brought back so many memories of my own childhood that I had to share them with my children. Now I have the fondest memories of reading those books together. I’m not sure I’ve ever read an author as perceptive to the inner lives of children or as empathetic to everyone, even adults and bullies, as Mrs. Cleary. I’m so grateful for her books.

I am loving all these stories about Ramona. 🙂

These books are a timeless treasure from my childhood.

I read Beverly Cleary’s books every year to my classes of second graders and they loved every minute of it, as did I. Her stories were so believable and appropriate; many children had a pesky sister or cousin like Ramona or a bossy older sister or cousin like Beezus. Her books used standard English, unlike many of the books for children who were seven or eight years old. I taught in a small rural village in northeastern Ohio, and we could easily transport ourselves to Klickitat Street in Oregon through her wonderful storytelling skills. I’ve been retired from education for almost fifteen years, and the number of former students who mourned her passing was touching, to say the least. Such a talented and beloved writer…

I read the Romona books over and over, again and again. During the summer library reading program, I would check them out multiple times even though I couldn’t add them to my reading log more than once. Of course, being an older sister, Beezus was my hero. Beverly Cleary’s books helped me develop a love of reading that I still enjoy today. This love of reading not only shaped my childhood, but was a major influence to me selecting English as a major in college, so I feel it has shaped my entire life.

The film has a lot of the wit and heart of the originals.

I read many of her books as a youngster, in particular the Ramona and Henry Huggins series of books. They were a big part of mine and many others of my generation early foray into reading.

I didn’t know her or her work but she seemed to be a lovely lady who lived a full life making kids happy. Why isn’t the world full of people like that?

A fine record of a long life.

What a lovely article. I can’t stress enough how wonderful and important reading books for children really is and how it is fundamental to their growth and understanding of other subjects and of life itself. I can see it in both my sons and their use of imagination and quick witted turns of phrase and even in their understanding of other languages.

I absolutely adored Ramona and felt i could be a princess and still ride my bike and play with earthworms and rolypolys. I felt a part of her book snd felt the many adventures and utter delight in each book. The books were written through the minds of children, simple and raw and brilliant. So many of us were Ramona. We could just be ourselves, no peer pressure.I turned into an avid reader and read tons of her books and now that I’m a mom of daughters, I also spread my love of reading and my love for all of Beverly Cleary books to them. These books will always be enjoyed snd I thank Beverly Cleary for allowing us to run wild and free with Ramona and having the best childhood ever.

For me, Ramona seems utterly relatable. Nice job with this article.

Those stories and characters are still relevant today. RIP Beverley Cleary.

Cleary’s books were among my favourites when I was a child, and I was delighted when my daughter (who is now a teen) declared her love for them when she reached the right age.

A thing that struck me, rereading them as an adult, was how subtle Cleary could be — about the employment struggles of Romona and Bezzus’s father, for instance, or how Ramona and their father had similar characters (including an artistic bent). The books thus have this perfect combination of directness and subtlety — addressing children on their own terms and yet never speaking down to them either. I know many would think it goes too far, but I have always classified Cleary as a genius.

We’ve been splitting our reading nights for our soon to be six year old son. Lately, on mom’s night it’s been the Ramona series and on dad’s night it’s been the Borrowers series. Two completely different experiences, but they are both equally loved.

For an assignment in 6th grade in 1980, we were asked to write a letter to our favorite author. Most students did not get a response, but I did in the form of a very personal handwritten letter from Mrs. Cleary, one of my most cherished memories. So grateful that she took the time.

My third and fourth graders loved Beverly Cleary books! We read them every year. For part if our writing classes, the kids and I would submit new characters or a change in plot to Mrs. Cleary along with pictures, and she would write the class a personal letter thanking us!

What I loved best about the Ramona Quimby books was that you could see inside Ramona’s head. Even when Ramona did some pretty terrible things (such as destroying a classmate’s art project), you could understand the emotions leading up to her actions. Ramona as a character had oodles of glaring faults, just like the rest of us. No wonder she was so relatable.

I read the books to my kids 25ish years ago, to my grand two-ish years ago, and again to my grand, at his request, during the past year. We recently read Ramona the Brave, in which Ramona is experiencing a struggle year with serious growing pains and a teacher who is just a little more rigid than Ramona is ready to navigate. Her frustration continues to build in a chapter called “Ramona Says a Bad Word.” Her parents have just received her progress report, which is honest in its assessment of Ramona’s need for better “self-control.” Ramona disputes this, of course, but her internal monologue unexpectedly made me choke up: “She hardly ever raised her hand anymore, and she never spoke out the way she used to.” Ever felt like you had to totally shut down to be accounted as “good”? Yeah.

That’s why I don’t think it’s possible to outgrow Beverly Cleary books.

I remembered the “Guts” thing, but had forgotten about the progress report. And sadly, some teachers still expect or encourage kids to “shut down” in order to be considered “good.” This is especially true for neurodivergent, disabled, or gifted children, because unfortunately teachers are taught that most kids fit into a box, and those who don’t fit, have problems. It is almost never considered that the problems are not the students. The problems are the presentations of school and learning.

I also remember being a young Ramona reader and thinking, “Why didn’t Ramona just say directly what was going on or what was bothering her? Why didn’t she just say, ‘I don’t raise my hand or shout out anymore, so I don’t know why Mrs. Griggs is still saying I have no self-control?'” But looking back, I realize that even as a kid, my mind was operating on pure logic, which most first-graders don’t operate with yet. I also realize that, while it didn’t feel like it, I was growing up in a different era than Ramona. That is, my parents encouraged total honesty, but Ramona’s may have encouraged the best example of proper behavior. And in both our eras, the best example of proper behavior was/is, “What the person in power says, goes.” This makes me think maybe Cleary was being a little subversive, and I love it. 🙂

After reading Ramona Quimby Age 8 I instantly feel in love with reading and books. Some of my fondest memories from my childhood including going to the local bookstores to decide which Beverly Cleary book to read next. I was excited and surprised about 2 months ago when I discovered all of my Beverly Cleary books at the mom’s house packed away nicely. It was as if she knew how special they were to me.

Her stories made me enjoy reading. Something I still don’t do as often as I should. Most writers are boring to me but her stories were very enjoyable.

As a third grade teacher for 14 years, I read some of the Ramona books to my students.

I’d read her books in my elementary school library. I loved the so, they reminded me of my childhood. In fact, I just recently retired as a children’s librarian, I became one partly because Mrs. Clearly had been one, and because I so admired my own school librarian, Mrs. Read.

Too many people write stories for children. Dahl got it right. He didn’t write stories or children, he wrote them for grandchildren: murder the parents on page one and let the protagonist be terrified.

I didn’t learn English until we moved to US when I was 8. The Ramona series helped me learn English and kickstarted my love of reading!

I wanted to be a translator when I was a kid (as in, for the CIA), and still love languages. I love hearing stories about what helped people learn English, and Beverly Cleary is, in my opinion, a great place to start.

My 3rd grade teacher read ‘Ramona the Pest’ at the end of the day, everyday, before the bell rang for a page or two.. It’s the first time I remember wanting to stay at school involuntarily. Hooked ever since, and love sharing her with my 6 year old son.

We started “in person” school again today in Kent, WA. Been out for 13 months. My read aloud for my third grade class? “Ramona the Pest.” I’ve read this to many classes. My kids love it and it introduces them to Beverly’s other stories.

Congrats on starting in-person school again. I’m sure Ramona will bring some much-needed comfort and humor to your kids.

Loved reading because of Beverly .. she has inspired me to keep reading through out these years. I loved all her Ramona books. Loved Ramona the Pest lol . She has always left an impact in my life.

She really understood childhood and adolescence; the angst, the fear, and the courage it takes to get through it.

I have loved Beverly Cleary throughout my life. She understood kids and the difficulties and struggles of a young family of modest means. The kindness of her created worlds helped me realize that not all adults are mean, short-tempered, and disinterested in the children around them. She gave me hope.

Because I really was Ramona Quimby Age 8 in the 3rd grade and it felt like she wrote that book for me! It was very personal. That writer-reader connection led me to read Socks, Ribsy, Dear Mr. Henshaw…I just connected with Beverly’s writing instantly!

Ramona the Pest was a significant book for me when I was a kid. I was in third grade and had begun to struggle with paying attention in class, something that I’d never experienced before. (Significantly, 8 is around the age where attention disorders begin to show in children). My third grade teacher definitely considered me to be a pest as a result.

Seeing a reflection of an imperfect child in media, one whose teachers also find her to be a handful and who sometimes does things that others consider strange or outside of the unspoken social order can have a great positive impact on students struggling with learning or developmental disorders. Ramona makes mistakes, she misunderstands social cues, but she is still shown love. She is allowed to make mistakes and grow from them, though she is not expected to immediately morph into the perfect child. If nothing else, it made her more fun to read about!