Traffic & Sicario: Reevaluating America’s War on Drugs

Cultural landscapes and the media they produce are self-perpetuating forces; media is used to depict and reinforce elements of American society with the resulting product acting as a cultural artifact for future generations to inform themselves upon. The American War on Drugs is one such recent event that shaped its representative media to conform to the American status quo, whether through coercion or in a natural process. Former drug czar, Barry McCaffrey, even made it his mission to sign off on only the prime time content that reinforced this hegemonic, anti-drug view, going so far as to grant networks a deal on ad time as long as they pushed anti-drug narratives.

Now, approximately ten years after what has been deemed the war’s failure, scholars and filmmakers alike can approach the event with fresh eyes, with the cultural artifacts of these border films made during the war acting as reminders of American mentalities. 2000’s Traffic, while unconventional in some ways for its depiction of Mexicans in the conflict, repeats many of the popular consensus’s talking points depicting the conflict as a noble crusade. 2015’s Sicario offers a far different take, rife with moral ambiguity and inversions of archetypes.

Traffic

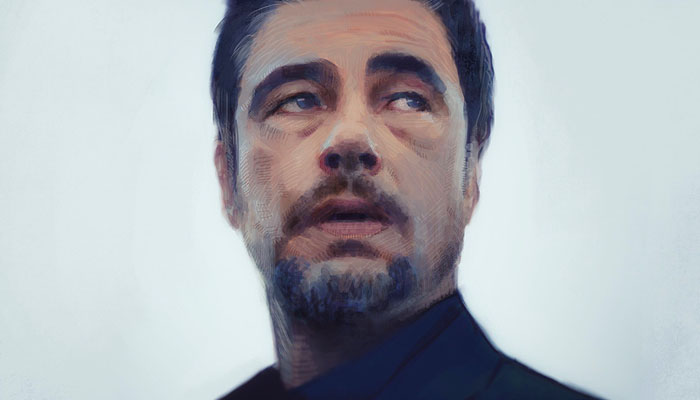

Traffic uses multiple storylines to depict the actors in the War on Drugs in a variety of settings; officer Rodriguez (Benicio del Toro) attempts to fight corruption on Mexican soil, drug czar, Robert Wakefield (Michael Douglas), works with Mexican officials and struggles with a heroin-addicted daughter, and DEA agent Gordon (Don Cheadle), fights cartels directly. This allows a wider breadth of perspectives on the conflict not afforded by prior American-made media, namely through the story of the Mexican Javier. This storyline’s dialogue is spoken solely in Spanish and prompts a Mexican perspective that is not antagonistic as before.

However, the character of Javier embodies the same narc cop tendencies most prior anti-drug media has portrayed. Camilla Fojas describes his character as resembling “the righteous hero alone in a sea of NAFTA-esque corruption [which] derives from a U.S.-based cowboy mythos, but in this case it masquerades as Mexican to fulfill the larger political agenda of expressing the need for better cooperation of Latin American governments in U.S.-backed and based drug control programs”. 1 Indeed, Javier is dramatically pitted in a fight to do the right thing when it turns out practically all of Mexico is in league with the cartels. The lone, morally-determined wolf in the war on drugs is an American trope transplanted onto a Mexican character, which also reduces any of America’s complicity in the process.

Mexico itself is depicted as a near-dystopian wasteland shot in an acrid yellow filter, rife with corruption and in desperate need of salvation. Javier’s choice to testify to the DEA about Salazar is not only morally just (done in exchange for electricity in his neighborhood so children can play baseball at night), but framed as the only reasonable decision for any audience member to make circumstantially. However, this premise restates the erred beliefs that kickstarted the War on Drugs in the first place, 2 that there is a clear enemy in Mexican drug cartels and the corrupt government that supports them. This generalization continues in the following storyline, which proposes a solution to the drug trafficking problem in the form of U.S.-Mexican cooperation.

Douglas’s Wakefield is an Ohioan drug czar whose anti-addict approach strongly resembles that of former drug czar, General McCaffrey, except the character is humanized by having a heroin-addicted daughter. His press conference illuminates the hypocrisy of the 10-point plan which labels potential family members as the “enemy”, a realization the real McCaffrey did not come to. This still comes at the cost of indirectly labeling Mexican drug traffickers (and perhaps the government, too) as the bad faith actors, saying “68 million children have been targeted by those who perpetuate this war, and protecting those children must be priority number-1”. His language and seeing the effects of addiction on his daughter, Caroline, are vehicles of pathos that help further shift the blame onto Mexico, implying the country is not only solely responsible, but dragging on the conflict.

Furthermore, Douglas’s casting is rooted in his epochal castings of the ‘80s, the start of the Reagan-era, anti-drug wave. Here he is the neoconservative figurehead many likely identified with, his harsh policies a result of (in this case) direct victimization from the drug trade in the form of an addicted daughter. The premise is the worst fear of every father of the early 2000’s, but Wakefield’s position as drug czar empowers him to do something about it.

Sicario

While Traffic takes the then-popular stance towards the War on Drugs and its causes (chief among them, blaming Mexico), Sicario is far enough removed from the conflict to offer different explanations. Screenwriter Taylor Sheridan envisioned this film as the start to a trilogy dealing with themes related to the modern American frontier. And despite it’s modern furnishings, there are several traits inherent to westerns and border films, namely in the protagonist, FBI Agent Kate Mercer (Emily Blunt).

A semi-reluctant lead, she agrees to join the DOD-CIA task force under the condition of bringing those responsible for two officer deaths to justice. Already she resembles the “narc” cop concept described by Fojas as a “good but maverick cop, the “narc” stand-in who works alone on a moral mission against a Latin-o American drug empire deemed a nightmarish system of late capitalism”. 3 Only in this film, her powerlessness to bring about justice is compounded by her outsider status and the true nature of the War on Drugs being a lawless and immoral free-for-all.

The title alludes to the character, Alejandro (Benicio del Toro), “sicario” being Spanish for the word “assassin”. The film suggests that morally-determined officials like Mercer cannot cut it in this conflict, leaving only professional killers like Alejandro, to get things done. This further implicates the U.S. in the conflict as they utilize assassins to do their dirty work, use Kate purely for the legal jurisdiction her role provides, and consistently engage in murder and torture for their gains.

The post-drug war Mexico in Sicario represents a vacuous heart of darkness that swallows up those who dare to step foot within it, Alejandro explains how out of place Kate’s sense of right and wrong is here with the film’s last lines; “You should move to a small town where the rule of law still exists. You will not survive here. You are not a wolf. And this is the land of wolves now”. This implies that law does not exist on the border, neither on the Mexican nor the American side. The revelation that American police officer Ted (Jon Bernthal) works for the cartels is proof of this. The Mexico of Traffic is certainly comparable, but not because of American involvement as in Sicario.

Settled Accounts

The moralistic pursuits of Traffic cannot be explained in Sicario; there is no Caroline character for the audience to see the long-standing effects of the drug trade within American borders, and whilst the Sonora Cartel is vile, the U.S. task force rivals them at times. All this takes the issue of the War on Drugs out of the hands of civilians and onto bureaucrats and operators whose political motives rival the moral pursuits of McCaffrey’s vision for America.

The actions of lead characters in Traffic were always done for the greater good of the innocent, while in Sicario this concept of a noble crusade is highly questionable. Each side of the conflict have significant flaws; the Sonora Cartel kills judiciously to send a message, but the task-force frequently engage in extrajudicial killings and torture just as much. In the case of the crooked Mexican cop, Silvio, the audience is allowed to emotionally bond with his family before he is surreptitiously executed at the film’s end by Alejandro, all this before killing the innocent family members of Alarcon before him. For the two officers killed by an explosion in the film’s opening, the task force ends up killing scores of cartel members, some of which are like Silvio, family men caught in a land of wolves. The majority of Sicario’s Americans are not Traffic’s narc cops and politicians, but rather career soldiers and bureaucrats who, more importantly, are uninterested in the moral ends this war would bring.

Sicario also illustrates the retaliatory method by which the U.S. operated in the War on Drugs; rather than curtailing incoming supply and incorporating drug treatment programs, the American way is in militarization and an attack on foreign soil. According to the conflict’s actors, the ends justify the means; Matt tells Kate “until somebody finds a way to convince 20% of the population to stop snorting and smoking that shit, order’s the best we can hope for. And what you saw up there was Alejandro working toward returning that order”. At least in Traffic characters like Wakefield have a change of heart upon realizing the antithetical nature of the war. The aggressors of Sicario not only are aware of the violence they perpetuate, but are complacent in it, and offer lackluster explanations for why it continues instead of taking any part of the blame. In other words, the motivation for fighting is clear and moralistic in Traffic, but it is difficult to even discern why the task force in Sicario (and America in commentary) continues to engage in this conflict.

Much like how 1968’s Green Berets and 1979’s Apocalypse Now offer startlingly different takes on the Vietnam War, the time between the release of Traffic and Sicario has allowed reflection on the War on Drugs. In the former, a more neoconservative approach is retained, encouraging Mexican cooperation with the U.S. and using Mexican characters to embody the narc cop ethos from the start of the war (in the form of Javier). Sicario, however, reasons that America isn’t faultless in their pursuit of this conflict, and that any moral motivation for doing so has been lost in a tangled web of bureaucracy and politics. In another ten years, there may be another film released that defies both these works’ conclusions. Thus the creation of media to reflect real-world events, often as they unfold, perpetuate a self-sustaining cycle of conclusions and reevaluations.

Works Cited

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Sicario has some great sequences, but I left the film with one question going around in my head: what was the point of Emily Blunt’s character? She does virtually nothing in the story other than tag along with the people who actually have agency, asking questions and looking horrified at the answers. You could remove the (supposed) central character and it would barely affect the story. Indeed, I ended up wondering if her character was the creation of a writers’ room round-table organized to help fix up a script that had a set of striking set-pieces and scenarios but nobody with whom the audience could identify, and no reason to give any exposition.

i take your point. i would argue that she shows how they depend on a sheen of legality and how they exploit the relevant agencies.

I want to see Traffic again and give it another chance. I always lose it among the brilliance of stuff like The Argentine, Guerrilla, The Informant!, Out of Sight, The Limey, Haywire, Erin Brockovich et al. I just remember Michael Douglas’ daughter’s boyfriend as a device to burp facts and figures and condemnation at Douglas/the government when someone in his position would’ve actually STFU.

The original tv show was better.

Traffic is a great example of a kind of film that doesn’t get made often enough – one that tackles a massive, complex and multi-layered subject and tries to show you it from lots of angles. The Wire did it, but then again it had over 50 hours to do it in. That Traffic makes a good go at it in under 3 is pretty impressive. The only film I can think of that’s comparable is Syriana. Both are films for people who like to pay attention – huge topic, ensemble cast, complex interweaving storylines, and both hugely underrated.

Loved it. Has all the elements you could want from an ensemble and they gave it their all but Benicio del Toro is operating at even a level above of the rest.

I’m a big Soderberg fan but Traffic has aged terribly. Nowhere near as good as the C4 original. And that’s another thing that’s aged terribly: C4. It used to make amazing TV.

The TV series was much better with the great Bill Paterson

That look that del Toro gives Vargas in the car after Vargas has betrayed them both is one that is burnt in my memory.

I was looking forward to Sicario but was seriously disappointed. Cant understand why it’s received so many positive reviews. To me it was confusing, cliched and pretentious. What was the point of the Emily Blunt character? She might just as well not been in the film. Prisoners and particularly Incendies were very good, engrossing works. This was just silly.

Plotline wise, the point of her character is to allow the CIA to operate across borders. They cant unless attached to a domestic agency. Hence the need for her character to tag along (and therefore why they didnt want her partner initially, the lawyer, who would know exactly what was going on). but her character was more to illustrate the moral ambiguity that ensues in the region between Mexico and the US. An honest question though: was it hard to really understand those intricacies in regards to the need for Emily Blunt’s character? I only as because I saw it with someone who loved it but after the movie i still had to explain to them why Josh Brolin’s character needed Emily Blunt in the first place.

Sadly, I agree.

I went in with high expectations as I have loved the director’s previous 2 pictures, but I was very disappointed. After a great opening, the film never really happened for me. I felt like it kept going round in circles with no real payoff. I understand that the film was probably supposed to be filled with unlikable characters, but Emily Blunt, who I usually love in everything played a frustratingly weak and somewhat pointless character

I would have loved for a different ending. Now it is as if nothing really happened with Blunt’s character throughout the movie. But I would have loved an ending where she would become immoral as well, as in highlighting that this war has this effect on the people wanting to end it. Which is basically the premise of the movie.

Love Villeneuve’s work, like Incendies and Prisoners I found Sicario genuinely chilling -particularly with Jóhann Jóhannsson’s brilliant score – and very, very intense.

I saw Sicario recently and loved it. Amazing cinematography and tense performances. Particularly Benicio. He needs to be in more films, I feel like I don’t see him enough.

This guy is the man. Any film with him in it is automatically improved.

He’s starting to look like an older, hispanic Brad Pitt.

Drugs won that war.

Upon first viewing of Traffic, I thought it was a great movie, and then I saw the original Channel 4 series and it became very clear that Soderbergh had declawed and defanged the original, propping up the policeman and politician characters as heroes while deleting the story line dealing with the struggles of a poor poppy-growing family, perhaps the best part of the original. A compassionate, realistic and humane multiple-part series was turned into yet another only-law-and-order-can-save-us one-off movie.

I’ve seen Prisoners, Enemy, and Incendies, and enjoyed all three. Shamefully, as a Canadian, I didn’t realize until now that they all shared the same director. Enemy in particular is one of the strangest of films, and seems to have been pretty much overlooked by most film fans, but I urge anyone who hasn’t seen it it take a look. Its landscape (a washed-out Toronto) is urban but feels oddly empty, and there are surreal aspects that haunt you long after the closing credits. Gyllenhaal’s performance is also notable. Going to check Sicario next!

Villeneuve is a fantastic director, I immediately felt a lot better about the Blade Runner sequel when I heard he was attached.

Incendies is a brilliant piece of work, incredibly intense with twists and turns right up to the very end. Highly recommended.

I really quite like this director. Prisoners was quite underrated, I thought I was excellent, not least for the brilliant cinematography!

America taking steps to legalise drugs hopefully takes the power away from the cartels. Hopefully Europe and the UK can soon follow suit.

While I like Traffic I actually think Gaghan’s Syriana is a better film. I struggled to keep up on first viewing but still go back to it years later because of how layered it is.

Yeah, Syriana is better.

Traffic feels horribly cliché these days. Some of it not entirely Soderbherg’s fault in that the heavy on the filter style he pioneered in the 90s was nicked by everyone.

Syriana? What a sprawling mess of a film.

A lot of people seem to have given up on Syriana because they couldn’t follow the plot. I think it’s an amazing film – it’s complicated because it’s about a complicated subject, but it really rewards you for paying attention.

Also worth mentioning that these films show Hollywood can make some proper grownup movies with A list casts. It doesn’t have to be all CGI and spandex.

Syriana? What a sprawling mess of a film

I really like Traffic and have rewatched it a number of times. Catherine Zeta Jones is very good in it, as is Michsel Douglas, and Benicio del Toro does his thing brilliantly. HOWEVER, it’s not cliche-free: the “innocent white girl pimped out by black man in ghetto without names or faces” subplot could have been straight out of a reefer madness moral panic movie 50 years earlier. Equally, the use of the hazy red filter for scenes in Mexico and the clinical blue filter for Washington/US scenes rehashes old passionate/mystical/Hispanic vs rational/logical/Anglo stereotypes. (I suppose that the fact that every other Hollywood director used the same trick for every film set in Mexico for the next 20 years and turned it into a cliche can’t be blamed on Soderbergh).

I seem to recall a lot of criticism of the Traffic more recently although I have yet to understand why. It’s not a masterpiece and a bit clichéd, but it’s certainly pretty scathing about the drug war at a moment when most Americans still supported it, and builds out the ensemble characters far better than many films do today.

Superb film, Sicario. Reminded me of the bleak, existential films of the 1970s. Villneuve’s directorial style is minimalist; the camera lingers on the actors’ faces for long moments. There is little dialogue, it’s all in the emotions on people’s faces.

Sicario is another in the line of an increasing number of political films which exploit the tensions of a globalised world; and yet, to its credit, it wasn’t attenuated by cheap heroism or an act of redemption, as others have been.

Villeneuve’s work does raise the question of what makes a satisfying film. I do not have to deny an appreciation of the excellent direction and cinematograph to admit that I found Sicario difficult to enjoy. Its message is extremely bleak and, despite calls from the Mexican side to boycott the picture, portrays the Americans in just as unflattering a light.

While Sicario excels in the frantic, claustrophobic, ambiguous terms of its own drama, it only hints at the ramifications of these drug cartels and the way in which authorities fundamentally exacerbate the problem by seeking to gain ‘control’ rather than a remedy. The scene in which del Toro’s character finally catches up with Manuel Diaz is perhaps the most powerful of the film, admittedly with several to choose from; but I think the unique thing about that atrocity is that it was a microcosm of what the film really points towards through the CIA and other factions: the West’s aggressive stance against crime belies our complicity in its global structures.

That ostensibly idyllic family with its mansion and fine cuisine–although the father defecates fatally close to where he eats, as the intrusion proves–could stand for any wealthy indulgence. In short, recreational drugs kill Mexican and Colombian children. The final scene, where the fatherless child’s football game continues through the gunshots, confirms that such terrors have become inseparable from daily life; just as migrants only cross waters because they feel to do otherwise would mean the destruction of their families, the Mexicans and others allow these tragedies to unfold because of systematic poverty and inequality.

i really like your comment. i am also more appreciative of the film than loving it. it is just too bleak to be enjoyable.

I loved Sicario. Especially admire the cinematography and score. However, I’m grappling with something here… Can someone explain to me how the film wasn’t just using tragic conflict for a thrilling and suspenseful entertainment? That the film had a point that it was making that merited this particular story being told? And being told in this fashion?

In the end it’s the writing that lets it down.

Ahh… Sicario. My only gripe is the focus on Blunt’s decent into bothersome silliness. Yet this is dealt with well enough when Alejandro looks upon her frail, fallen soul, almost fondly, and explains that she reminds him of someone he was once close to…prior to re-affirming the trajectory which only a bullet in his brain will arrest.

Watch thisover Bond every time. Strong female character, good script, solid action set pieces and a great look. Blunt for the next Bond.

The moment you discover Del Toro’s motivations and cause of his nightmares left me cold.

A good essay addressing the difficulties of what has been called the War on Drugs-a cute, but meaningless PR term created for political consumption. Both movies, critiqued well in this essay, show the frustrations, difficulties, and despair of trying to determine how to do something that, at least, seems effective at reducing drug use in the United States and reducing drug shipments from Mexico.

I love Traffic – even the minutiae is great – the banter between Luis Guzman and Don Cheadle. Soderburgh has a real eye for detail whilst confidently telling a larger story. This and Erin Brockovich are fantastic.

A really exciting brilliant film, I loved it.

I could definitely see a different film plot surrounding drug cartel issues; the culture has changed significantly since the early to mid 2000s.

I’ve never watched “Traffic”, though I’ve heard of it. I’ll watch it later to make a comparison with “Sicario” later on, which I’ve watched and rewatched because the plot is brilliant and Benicio Del Toro was excellent in it.

The points made in both movies got me curious, especially about the take on this War on drugs and how the characters were portrayed. The concept of morality played a big role in this war, which had been tackled in this essay. It was up to us to understand the point made: that our own morality could get lost and tangled up in bigger webs woven by more problematic issues. Justice? Even that concept can get muddled pretty easily and lose all of its aspects.

Seeing a task force use the same tactics as a cartel really forces people to reflect: are the good guys still any different when they’ve realized their methods don’t work and have begun to use the most unorthodox methods to get their targets? Are they still the good guys? In “Sicario”, you ask yourself this question because the end justified the means. As antithetical as this war is, the American task force keeps going for reasons I can’t really pinpoint and justify, thus taking away all moralistic view in their actions. What they’re doing is disgusting, morally wrong… but they keep going. And they don’t care as long as it brings results.

This was a very interesting essay.

Drugs can’t be fought in a way,but regarding teen people I don’t think if the government allowed weed usage in medicine it would fight against home usage and that’s why I think they can’t

Villeneuve is definitely one of my favourite directors of all time; Sicario helped cement him in such high esteem. The film is equally engaging and grounded; it is a very visceral experience.

I was wondering what the author’s position was regarding the Sicario’s sequel and if that changes somehow his original ideas. But I am afraid that’s an answer that I’ll never get…

Twisted double talk. Traffic leaves one with a feeling of hopelessness and moral ambiguity.The bureaucracy is shown as ineffective. A drug lord’s wife is presented as a sympathetic character. The American side is just cops and robbers with neither the goods guys or the bad guys having anything but comic book dimensions. Michael Douglas as the neo conservative judge throws in the towel for illogical reasons.He gives up protecting his daughter from drugs. Even the somewhat moralistic Mexican cop gives up the fight for a deal that preaches prevention but begs the issues. Traffic is truly morally bankrupt but not for the reasons stated here. Sicario on the other hand, doesn’t shy away from the war. It is equally bankrupt in its own way in that it settles for less: order instead of victory. And it tries to prove that by having the Sicario act out of charater by killing the drug lord’s family to prove the cause is unwinable.Siracio is cut from the same cloth as Traffic-trying to portray Mexico as something more than it really is which is a totally corrupt, desperate and yet complacent culture. At least Sicario doesn’t pretend cooperation is the answer and doesn’t pretend at Mexican nobility. And yes the dichotomy of these two movies is yet another legacy of the Vietnam War but it is the phony legacy that we were defeated and that defeat is our only option if we choose to fight. We didn’t lose In Vietnam.Politicians gave victory away after it was once by refusing to continue to support the South after the peace.Yes I can hardly wait for the next media iteration of this war. And shame on you Taylor Sheridan for exploiting Mexicans to prove a specious point.

A good essay. A perceptive examination of two movies addressing drugs from different points of view.

A good essay on a good movie. I wonder whether there is some credibility to the whether the drug world is as portrayed as in this movie.