YA Book Series That Never End

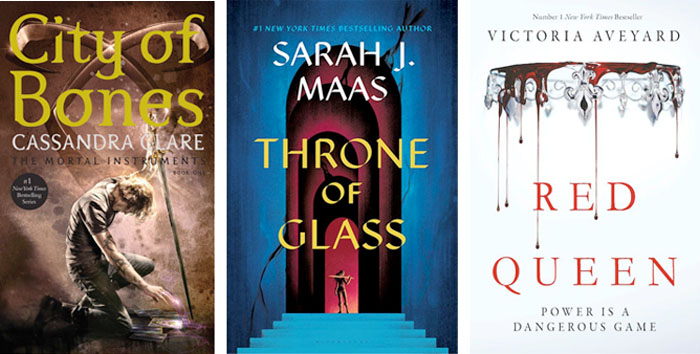

Cassandra Clare’s Mortal Instruments series, Sarah J. Maas’s Throne of Glass series, Victoria Aveyard’s Red Queen series … Most prolific readers of YA (young adult) fiction, or fiction targeted at an audience aged approximately 12 to 18 years old, are familiar with series that seemingly never end. Whether it’s a beast that grows and grows—in the ilk of Sara Shepard’s Pretty Little Liars series—or an ostensibly modest trilogy or five-booker that spawns further trilogies, prequels, sequels and so on—as in the three initial examples—expansive series are prominent in YA, especially YA fantasy.

Of course, massive series and multiple series are far from unique to YA or to the fantasy genre. Crime, in which series often tend towards the “episodic” (Nikolajeva 198), contains a good spread of sprawling series (hello Jack Reacher). Adult fantasy also loves the behemoth series, which, in cases such as that of Robert Jordan, can even outlive their author. Nonetheless, there’s a special penchant for series, particularly ones that “proliferate” (Wilkins 48), in currently popular genres of YA and upper middle grade.

So why do never-ending series have such a hold on YA genres including fantasy? And is the existence of these series good, bad, or other? Three key factors that play into the existence and popularity of such series are: efficiency, fans and proliferation. The below discussion addresses each in turn, while recognizing their variously overlapping and shifting elements.

Efficiency

“Laziness,” or a bid to make money easier might be less generous ways to talk about what is here described as “efficiency.” Serializing with efficiency in mind is author driven or publisher driven, and can have creative or commercial motivations according to authors. Similarly to many things in publishing, the likelihood is that it in fact has both. Authors can love their characters and not want to let them go at the same time as they see in series a potential to increase output and therefore in theory commercial success.

To pause for a moment on the output and commercial side of the equation, the idea generally goes that setting up a world and characters is a lot of work for an author. So, as a well-known British children’s author said, the more they can “squeeze” out of what they’ve already put work into, the better (personal interview). That way of putting it is somewhat mercenary, perhaps, but it recognizes that publishing is a business—a fact that most authors are obliged to acknowledge to some extent.

The idea that it’s efficient to serialize also recognizes demand from readers and therefore publishers to produce content quicker and quicker in an age where digital technologies mean instant gratification is increasingly the expectation (Wilkins 56). An extra short story here or a novella there might satisfy readers—and yes, also keep them excited about the world—while they wait for the production of another full book. And that book can typically be produced quicker if it’s in an existing series or world.

This talk of worlds offers an insight into the affinity between never-ending series and YA fantasy in particular. When “worlds” come up for discussion, the impulse for many is to leap to fantasy and its secondary worlds. Such worlds, and the characters who inhabit them, take setting up of a different kind to other worlds in fiction. So the “waste” of all that crafting for one book, or even three books, is often amplified in the fantasy genre.

Even so, the argument stands for all genres of YA—and really of fiction broadly: series are in part a tool that creates efficiency, and the efficiency increases with series length (Gelder 16-17). That’s not to say there aren’t downsides to the never-ending series model. There are many. For example, the efficiency of using a world that’s set up might be counteracted by the limitations of that world restricting the author’s subsequent ideas. Or the necessity to remember and not contradict details provided in books potentially written ten plus years prior might in fact slow things down.

If never-ending series were universally beneficial, no one would write or publish anything else. While there might be a lot of extensive series going around, that clearly isn’t the case. So they aren’t working for every genre, author, or for that matter, reader. But the efficiency that can come with serializing makes series that seemingly never end an attractive prospect, especially considering the nature of YA fans (Wilkins 48, 55-57).

Fans

Fans of YA—fantasy especially—whether they are young adults or not, are a very particular type of fan, characterized by their avid engagement, often voracious reading habits and strong emotional connection to what they read (Wilkins 48, 64). By and large, these fans want more of what they love. And it stands to reason that publishers and authors who are trying to make money will give them this.

When a publisher demands more from an author about X character or in Y world, this typically stems from reader demand for the same. Publisher driven serializing for efficiency generally comes down to success measured in terms of sales—it is efficient for publishers to produce what they have a good idea will sell based on the track record of previous books and an existing fan base. Fans and their purchasing behavior therefore influence decisions about the value of developing or extending a series.

The “avid fan” label aptly attributed to YA audiences brings with it behaviors such as the desire to curate collections. Young readers in the YA and middle grade spaces are likely to want to collect their favorite series (Watson 8). And it’s not only young readers who enjoy collecting. Anyone who’s spent time in YA fantasy Facebook groups or other social media equivalents will have seen shelfies showing off painstakingly curated and displayed collections belonging to fans of all ages. While such fan behavior isn’t unique to YA readers, its presence in these fan communities lends a further dimension to the prevalence of series that grow and grow.

It may be a chicken and egg scenario, but whether fans create never-ending series or never-ending series create fans, series suit avid fans who just want more of what they love. And series facilitate fans indulging their love by collecting books—and products related to them, which is where proliferation comes in.

Proliferation

The idea of proliferation draws together and extends the production and reception considerations above. Kim Wilkins describes proliferation as “one of the ways that fantasy texts offer glimpses, and hint at a much larger storyworld” that is not “containable” within one book, or even necessarily within the pages of books (52). Proliferation doesn’t happen only within books or only outside them, but in a myriad of ways relating to both stories and material objects. And naturally, it doesn’t relate only to fantasy worlds or to worlds where books are the initial product.

Proliferation happens so readily, and often successfully, in YA because of the appetite and participation of fans, who are offered a deeper connection to a storyworld by processes of proliferation—and also, of course, due to the motivations of authors, commercial and otherwise. As the above chicken and egg comment alludes to, there’s a cycle where the loop feeds back, leading to more and more series that never end because they work. Fan appetite leads to never-ending series, which feed fan appetite further. In that desire for “more,” proliferation flourishes.

To demonstrate how proliferation might look at work in series that never end, the following paragraphs touch briefly on the examples of Rick Riordan’s Percy Jackson world and Victoria Aveyard’s Red Queen series. Technically, Percy Jackson fits more in middle grade than YA, but it’s hard to look past the world of Percy Jackson as a contemporary example of textual proliferation. And of course, swathes of series “crossover” in terms of readership (Beckett). Harry Potter, for example, may start firmly in the middle grade camp, but most would agree it finishes in YA territory.

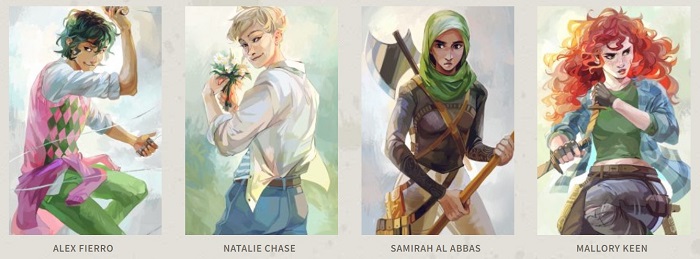

So, unashamedly bringing in Percy Jackson as an example, Riordan’s multiple series demonstrate how a world can proliferate and expand to distinct characters and stories within books. What started as the Percy Jackson series has grown into The Heroes of Olympus, Magnus Chase and the Trials of Apollo. Each of the series within the world shifts focus to a different set of characters, and often to a different part of the world, showing readers that more exists than they had anticipated. This ecosystem builds a richer world and gives Riordan space to play with different ideas and casts … though these don’t diverge too far from what readers expect and what was working in the first place. This harnessing of series to expand a storyworld keeps readers of the original series engaged—for the most part, anyway—and draws in new readers through ongoing visibility and freshness.

On the matter of downsides once again, spreading out series nodes by bringing in new characters after an original series that centers around one heavily branded character, à la Percy Jackson, runs the risk of alienating fans who really want more of that character. On the other hand, though, multiple series and the Percy Jackson approach allays one issue of long series that aren’t split up—namely, readers who come to multiple connected series part way through don’t need to go right back to the beginning to understand the story.

As mentioned above, proliferation happens beyond books as well as within them, and this is a major factor in building fandom. “Transmedia adaptations,” such as merchandising, interactive activities and reader groups that discuss and promote popular worlds, are some examples of proliferation beyond books themselves (Wilkins 1).

Wilkins discusses proliferation in relation to Aveyard’s Red Queen series, using the Scarlet Guard fan site as an example. As Wilkins describes it, through the site, “fans are charged with sharing links across their social media in order to be rewarded with previews of content and cover art” (54). Here, fans are actively participating in proliferation, effectively providing free labor to publishers and authors by spreading the reach of series and worlds. Notably, readers are participating by choice (Wilkins 54) because they enjoy feeling a sense of connection or proximity to the author/storyworld. Such activity cultivates the kind of fandom that encourages series that never end.

Fans want the worlds they are invested in to proliferate, and if authors, publishers and other industries don’t deliver (or even if they do), fans will often take matters into their own hands. Such participation spreads the worlds and characters of YA series beyond the books, creating space in both commercial and storytelling terms for more than what might originally have been perceived as the scope of a series. When authors fill this space, series that seemingly never end are one of the results.

It’s easy to see the YA series that never ends as nothing but a money grab. And certainly, instances would exist where that is the case. But there can be a lot more to the equation than meets the eye, and ultimately, readers are getting what they want and quite often demand. When there stops being an appetite for more, publishers and authors will typically move on, because publishing is a business. That’s a reality, whether for good or bad. The existence and popularity of YA series that seemingly never end therefore reflects the dynamic interplay between authors, publishers and readers in contemporary book production. It’s not always easy to tell what the core driver behind a never-ending series is, and nor, perhaps, is it necessary. Many observers are quick to insist on a stark distinction between creativity and commerciality, and to demonize the latter. But those who find joy in YA series that never end will continue to do so regardless, so those who don’t might as well let them.

Works Cited

Beckett, Sandra L. Crossover Fiction: Global and Historical Perspectives. Routledge, 2009.

Gelder, Ken. Popular Fiction: The Logics and Practices of a Literary Field. Routledge, 2005.

Nikolajeva, Maria. “Beyond Happily Ever After: The Aesthetic Dilemma of Multivolume Fiction for Children.” Textual Transformations in Children’s Literature: Adaptations, Translations, Reconsiderations, edited by Benjamin Lefebvre, Routledge, 2013, pp. 197-213.

Personal interview. Email. 2 July 2019.

Watson, Victor. Reading Series Fiction: From Arthur Ransome to Gene Kemp. Routledge, 2000.

Wilkins, Kim. Young Adult Fantasy Fiction: Conventions, Originality, Reproducibility. Cambridge UP, 2019.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

This reminds me of a question Chris Morris asked a random member of the public for one of his earlier shows: “Do you think people use too many words these days?”

What a question! I don’t know that I’d have an answer …

The wrong ones do.

Man, Harry Potter release days where something else, never have I seen that many ppl desperate for a book. Specially for the final book, stores everywhere around me opened early so people could go to the bookstores, there would be police at the line up spot and at cash register. People where terrified of the book stores selling out before they got a copy.

I’ll never forget walking through a dark mall at 6 something in the morning, surrounded by a huuuge group of ppl of all ages wearing wizard robes, all beyond excited. All for one single book.

Extreme fandom – I probably wasn’t in the right place to see it in action, but I would have loved to observe that kind of thing 🙂

I was hired as security for a bookstore back in ’07 for the final Harry Potter release at midnight. I was 22 at the time but still a fan. The bookstore was nice enough to let me buy a copy after all the pre orders were picked up. I did go home and read the whole thing to prevent spoilers. Good times.

Oh nice! What an experience …

I’m from 1978 and I remember when Harry Potter craze hit. To me it was mostly exhausting, because I could hear from the buzz that the books were just not my cup of tea, and I started getting a bit snarky on the subject, but a friend of mine who studied literary history at the time said: “These books get people who would never pick up a book, reading! It’s an amazing feat, just think about it!” and I had to agree. I never boarded the HP hype train, but I started smiling and waving as it drove by me, because I focused on how many more people might also get to ready my favourite books, compared to before HP.

I was not aware of the YA genre even existed when I was “YA age”, but looking back I have read some. It’s just that I’ve been reading adult literature too from I was like, ten.

I’ve recently read the YA books surrounding Sword of Kaigen, and the Binti trilogy, and tbh I wish they were there when I was a nine or ten yo kid. I would have loved them for sure. They’d have slottet in fine next to McCaffrey’s Pern stuff.

I know at least one author who writes fiction that gets labelled YA, but who is actually not strictly writing with young people in mind. My understanding is that she’s writing for adults who would just like to read something cool while feeling safe knowing that no PTSD symptoms or other nastiness will be induced.

I think that is a very worthy cause and I love that there is a space for it.

I don’t enjoy a lot of YA myself (I am one of those masochistic Malazan fans! It can’t get too grim for me!) but I really, really appreciate that those books are there for other people to grab them and seek thrills and comfort from.

That’s an interesting point about the author who is labelled YA but is writing for adults! I’ve come across some authors who were surprised about where their books were positioned in the marketplace, but most of them started out a while ago, when there was perhaps less info going around about how the industry works.

And I suppose the popularity of YA might encourage publishers to position things there if they seem like they could fit, even if that’s not the author’s intention.

My dad worked for FedEx during the Harry Potter mania and he had people following him while delivering around bookstores at some point they had to have special deliveries so people wouldn’t try to rob the delivery drivers.

Wow, that’s scary!

I really really enjoyed Throne of Glass. I love Celaena! She is a human version of a dipped ice cream cone.

That’s an interesting description!

Celaena is definitely the best assassin. But for a good and believable story about an assassin, look somewhere else.

I absolutely loved it! The characters, the plot, the writing. Everything. (Also I’m completely and utterly in love with Chaol)

The skill of the novelist is to make sense of the chaos that life often seems to be. If they can’t even end their story in a coherent, satisfying way…they probably aren’t doing a very good job.

I definitely like a satisfying ending.

There are some well written YA books that I’ve really enjoyed. Given I’m a big fan of fantasy and so much of YA dabbles in that, it’s a nice genre extension. There’s some real dross out there as well, but then you can say that of any genre!

I’m glad there are YA books you’ve enjoyed!

Great article. I work in a public library, and in my experience the YA collection is read by pretty much everyone except young adults – younger readers want to read above their grade, and older readers want to read below theirs, but ‘young adults’ (whoever they are) generally have better things to do…

I’m interested in the idea of reading up – I haven’t really considered it in relation to the other direction, though … So thanks for that thought!

What an interesting observation!

When I as was a young adult (i.e. early 20’s) I read John Taylor’s book Enough is Enough (published in 1975.) He warned about the philosophy of limitless growth and told us simply, ‘Enough is enough!’

The book proved to be prophetic. It certainly changed my life, even if my friends at the time thought I was a bit odd!

“Enough is Enough” sounds interesting! I’m curious about that now.

Like the greatest family films, books conveying deep meaning and enjoyment to both children and adults are special indeed…

…Reading books we read as children, like ‘The Hobbit’, ‘The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe’ and ‘Watership Down’ again as adults can invoke those extraordinarily powerful emotions and memories stirred when revisiting greatly loved places from our childhoods.

I love rereading things as an adult … Of course, disappointment does happen too.

Agreed.

I particularly liked The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe by C S Lewis. It was a great read. It also motivated me to read Lewis’s other books that were intended for adults.

I’ve tried reading some of my son’s YA novels. I think the themes are for young adults and I am an old one who can’t project any more. The last one I tried was The Enemy and found it dull and I didn’t give a shit about the YAs or the parents in the story but then my son wasn’t engaged by that one either so maybe not a good example. I guess it just comes down to taste but YA fiction is generally not for me.

Fair enough! I don’t think anything works for everyone, after all.

His Dark Materials are my favourite books, and they’re YA. Depends on the quality of the book, i think.

Though I suppose “quality” is subjective, too.

Serialisation in publishing is an interesting topic and I haven’t seen much written about it before. I agree with a lot of what you say. I would like to add that serialisation seems to tamper sometimes with the integrity of writing, and that its quality may be sacrificed for the sake of getting another book to market.

Ideas about quality and the pressure to get books out are so interesting – I find them particularly so in the case of authors whose debuts are successful and the pressure they then have to follow up with a sequel.

I like films that are 90 to 120 mins long, books around 300 to 400 pages, and I don’t like podcasts at all, simply because they waffle on and on without getting anywhere. Albums too, anything over an hour is too much.

I listen to a lot of BBC radio 4 podcasts. Most are about 25 minutes long, and few more than 55 minutes.

40 mins is the ideal length for an album, i.e. it should fit on 2 sides of vinyl.

In fairness, after a CD-driven period where albums regularly exceeded an hour, more artists are releasing short albums these days. Streaming has made the format more flexible – nobody’s going to complain if a new release is 25 minutes long provided it’s good. When we were paying £14.99 for a physical disc there was an expectation of quantity as well as quality.

Yes I’d agree with that. There are exceptions (Wu-Tang Forever, To Pimp a Butterfly, several electronic offerings, especially if mixed) but 60mins or less is the ideal!

Why are our attention spans so short? We should embrace the lengthy YA book series! 😉

Because attention is a very very very expensive cognitive resource.

I sure embrace them!

To paraphrase Shakespeare, “the plot is the thing”. If it doesn’t serve the plot, cut it.

Yes, I tend to like books that keep things moving in a plot sense.

It’s videogames too. They go on and on and on now. A good story campaign used to last 20 hours, now they all seem to last 60 hours plus.

And so much of it is padding, repeating the same stuff over and over again. Any emotional impact is dulled by the sheer length of them.

The Last of Us 2 being a case in point.

This trend is on TV too – I have been watching “The Sister” but last nights episode really started to drag. Last one tonight, four nights in a row. Could have been three episodes and an attention grabber/keeper. As it is, popping off to the kitchen to make a cup of tea didn’t matter much.

I certainly feel that in TV the economies of scale no longer allow for shorter form pieces, especially in period drama.

It probably costs almost as much to make 2 hours of drama as it does to make 6 and as such the trend in recent years seems to be toward elongated narratives that quite often simply don’t merit the extra run time.

Off the top of my head, I would cite the Mrs America thing from earlier this year.

I enjoyed it, but there was at least 3 hours that were nothing more than good quality soap opera. There was a much, much better 3 hour drama hiding within it.

Similarly the Getty kidnapped drama with Donald Sutherland from a year or two back. Could have been cut in half if overall quality as opposed to value for money was the pressing imperative.

With film and TV it is definitely linked to the growing need for content.

When there were just a couple channels to fill there simply wasn’t time to show everything but now the multiple channels and streaming services are desperate for hundreds of hours of content…

TV adaptions that might have been ruthlessly edited to 3 hours, can now run for an hour with no ads over a dozen episodes.

e.g. a short book like Normal People eked out pointlessly to 12 eps, 6 hours in total. I’ve tried several times and given up by episode 5

Absolutely – the HBO / Netflix effect. They have oodles of money and acres of slots to fill, and they want to pull you into their environment.

So episodes are extended and series prolonged to give you ‘value for money’ for your sub.

The Kidman/Grant Undoing is current example: good, but flabby. One episode in, and an hour older, but 90% of that was background (and some gratuitous ff nudity [so not all bad]). A proficient director – a Hitchcock – would cover all that in a few scenes, including showing all the retrospectively important things. And would move the story along.

The Last of Us 2 could have done with some cutting. The overlong intro and the epilogue perhaps. But it was 25-30 hours maximum, and I took my time. Otherwise I agree with you generally. These days I would be very happy for most games to run their course in 15-20 hours.

I love getting this perspective on things! Not being much of a gamer, I would have anticipated the longer the better – the more you get and the more time you can spend in the game. Interesting to see that’s not necessarily the case.

My idea of a good length for a novel has been indelibly formed by Penguins – easily spotted on charity bookshop shelves not just because of their orange (or green) spines but also their slimness. Brevity, economy, and a great many classics of 20C British literature.

I am being tempted to go out and buy more of these when I can. It is good that we get revivals of books such as the Simenon novels, but we also need books of this length to be easily available from a wide diversity of contemporary authors too.

They are rather attractive, aren’t they?

Love YA books. I recently re read a bunch of Robert Cormier books. Loved them as a kid and loved them again. He never wrote down to young people. Showing my age there.

Many a time have I heard how important it is for those writing for young people not to write down to them!

I think I remember reading that John Locke spent 35 years working on “An Essay Concerning Human Understanding”, and in the end he didn’t so much finish it as his friends took it away from him and published it anyway.

Wow, that’s something!

I still read the teen and young adult novels that I ‘borrowed’ from my mother’s book shelves. Lots were written in the seventies by the likes of K.M. Peyton, Penelope Lively and Antonia Forest and they are still absorbing stories with universal truths about human nature. I also like the New Zealand author, Margaret Mahy, who wrote more in the eighties. And I still love the children’s book series, Just Jane, by Evadne Price, which is like The Simpsons in the way that it seems to be for children, but is really hilarious for adults, too.

I love this take on YA novels 🙂

Glad to see this made the lineup, and honored to have worked on the revisions.

Thank you for your help and feedback!

Oh YA, as a past bookstore employee and writer I find this category well extremely interesting. In one way it is the bridge between childrens and adults books, but in another way a kind of no no section for some younger people. I have said this before bookstore employees are often required to say that some YA books contain strong trigger points for young adults that may be upsetting. Yeah I know many people with in this age range are mature enough to handle the content, but let’s be honest some arn’t quite ready for it.

Now where YA really interests me is that it allows a book series to last a long time as characters can grow and age with its target audience or fans. For many authors that becomes such a benefit as one allows them to fulfil their dreams as a published author and two to keep them economically stable so they can support themselves and their families. Let’s face it not all authors are in the same position as J. K. Rowling; many are scrapping at the bottom of the piggy bank to survive or working other jobs to keep a roof over their head.

Truely many many book could be in YA category but publishers have motives to keep them in normal categories to avoid the YA stigma, but others jump at the chance to be known as YA. Some books are even weirder like Harry Potter these days often found in childrens, YA and its own shelves or display for both the original books and the illustrated versions, acting if it has transcend being in any category or genre.

Thanks for sharing this perspective. I’m fascinated by series where the characters age ostensibly with the readers! There are so many interesting factors to it in both practical and creative terms.

This is indeed an interesting dive into the facet of YA literature. Very well written, and you left me with a lot to think about.

Thank you so much 🙂 It’s definitely an area that keeps me pondering!

I re-read Isabelle Carmody’s dystopian fantasy Obernewton series in my early 30s and adored them just as much as I did in my early teens. Far from light reading though!

Carmody’s books do seem to come up a lot as ones that appeal across a lifetime!

I’m 25 and just now moving out of the YA section. I found the adult fantasy section a bit daunting and most of the well known books had Male leads, there’s nothing wrong with that but obviously I’m going to connect more with a female lead so I stuck to YA where majority of the fantasy books had female leads.

I feel the same – thankfully I’ve seen a ton of modern day fantasy books breaking the traditional: “Fantasy and science fiction are only for men” trope. Binti, The Fifth Season, the Lightbringer, etc. are a few examples of how fantasy and sci fi are becoming more inclusive, but there still remains what I like to call, “The old boys club of fantasy lit” where you still have traditional male leads and sexualized side female characters. Historically there have always been women in fantasy, but they often had to publish under a male name because publishers didn’t think a woman could sell in a “male dominated” genre.

Yes, I also enjoy the female leads in YA. Though I think when I was growing up reading middle-grade and YA, I predominantly read books with male protagonists and didn’t consciously think anything of it.

As someone who is about to turn 30, I’m right in that age bracket where YA titles are becoming “taboo”. It’s annoying. I like reading YA because they are often lighthearted with a good take-away at the end. However, some adult readers view reading YA as “immature” or “childish” and try to shame readers for enjoying them. I say, read what you want to read. If you enjoy YA, read it and don’t care about what other people think.

Absolutely! Read what you want to – definitely the way to go 🙂

I’m 40 and still read some”YA”. If it’s well written, it doesn’t matter to me if it’s marketed to high school and college kids.

I just finished reading Deep Water by Lu Hersey, and apart from the fact that the main characters are teenagers (three of them, anyway), you get so caught up in the pace of the action that you almost forget that you’re reading a YA novel…

I don’t know that one – might have to check it out!

While I had previously thought about how many YA and MG series are long-running, I hadn’t realised just how many of these series are in the fantasy genre. I agree that the world building element of fantasy contributes to the viability of writing sequels for this genre, in contrast to books focused on everyday settings.

Yeah, when I stop and think about it, fantasy definitely comes up a lot – though I could also be biased by my own reading 🙂

Y.A is a complicated area, as while it provides enjoyable reading experiences, lately it has been seen as a replacement for literature

I remember reading Pretty Little Liars for the first time and thinking what even is this? The writing was not for me and the plot was not the best in certain areas. I read the first four and regretted it instantly. 😂

Really enjoyed your piece regarding YA lit. and your thorough analysis of Transmedia adaptations. Marketing and business surrounding someones imagination and literary concepts is such an interesting topic – especially the way the Harry Potter series has been impressively monetised, example of films, merchandise and obviously the theme parks – which I can imagine is an authors dream

Thank you! Yes, I find it all very interesting. And Harry Potter is a fascinating case to look at, but always with an eye to the fact that it’s an exception rather than the norm 🙂

You are so spot on about the collectable value of YA series! I am very guilty of this–I basically have a Percy Jackson shrine, as a whole shelf on my bookshelf is dedicated to PJO books and memorabilia LOL

I love that! I think it’s great that we get so much joy out of the stories and characters 🙂

I’ve loved YA books since I was in my early teens and think am grateful that so many novels of this genre were developing as I have been growing into adulthood. I think that the experience of growing as the characters grow demonstrates the authors’ ability and opportunity to include themes and topics that are more mature in their later books than the ones that were included in, for example, the first book of their series.

It’s interesting to think about it as an opportunity for the authors – definitely makes sense, as there would be things not appropriate for younger readers that authors might want to explore in their worlds and with their characters.

I think it’s sometimes frustrating to have so many unresolved book series or a series that goes on and on. Sometimes the story just loses its appeal to the reader because it stretches on for so long. But at the same time, fiction is always a way to lose yourself. And you want the story to never end because you want that outlet with the characters.

Yeah, I get your point about frustration – including when reading a series that’s not yet complete.

Storylines like the Percy Jackson one deserved a more conclusive ending, like after The Heroes of Olympus. The two series in one were a perfect length to tell the initial tale and develop characters. While the other books also exist in the same universe, I don’t think the characters should have been reused or mentioned, SPOILER ALERT, with stuff like Jason’s death just being so unnecessary for those that read the original series. Sometimes it is better to just leave things when they are good than to drag them on. A lot of fantasy romance series do this too, where they add more books after the fact with kids, and then the kid’s kids, and it all just spirals. And don’t get me started on the authors that go back years later to add in a new book to a series due to fan demand and absolutely OBLITERATE the characters’ original personalities.

This is interesting! I know I often struggle to adjust when my favourite characters are reused as side characters in a different generation’s stories – I typically don’t like endings, but nor do I necessarily want to see the characters after their heyday!

What a question, brilliant!

I am an unapologetic lover of these series. Personally I love getting to stay with characters for longer periods of — but I would never claim these are quality stories (especially by the later books).

One thing I love about these authors though is getting to witness the evolution of their writing. Like Cassandra Clare for example, her current writing is incomparable to her earlier works.

Interesting point about witnessing development of craft – makes me wonder if there’s a research question that could be explored with what’s there to see!

I think the fan interaction aspect in this piece is particularly compelling as I can’t help but connect to the ever expanding practice of fan fiction that has become so popular on various platforms. I think with any book (or series) that’s done well, the readers will always be left with a sense of disappointment at the end of something they loved and when this need is not satisfied by publishers to consume more, many fans take initiative into their own hands. This makes it silly for the author and the publishing company themselves to not profit off of this obsessive behaviour.

I find the emotional investment of fans fascinating to ponder! Considering disappointment from my perspective as a reader, I always think it’s a fine balance. There have been times when I’ve been more disappointed that a series didn’t end when perhaps it might have been more satisfying for fans if it had. But I suppose it’s difficult to tell until after the fact 🙂