Before ‘The Counselor’: Examining the Novelist as Screenwriter

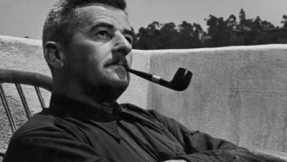

Set to release for this fall, The Counselor, is the latest Hollywood feature film to be penned by a novelist. Cormac McCarthy, author of Blood Meridian, No Country for Old Men, and The Road among many other works, has written the screenplay for The Counselor. While the one-line synopsis of the film is quite underwhelming, “A lawyer finds himself in over his head when he gets involved with drug trafficking,” we can surely expect this Ridley Scott helmed film to be much more explosive and dynamic. Bradd Pitt, Cameron Diaz, Javier Bardem, Penelope Cruz, and Michael Fassbender (in the role of the aforementioned lawyer), star in this highly anticipated thriller. What little, but enticing, bit of the plot and scenario of the film the trailer reveals will strike fans of the film adaptations of The Road (2009) and No Country for Old Men (2007) right in the gut. Brilliantly, that is.

Insight into the deft concision of McCarthy’s screenwriting broadened just slightly for readers of The New Yorker this past June. Readers were given a small feast when an excerpt from the screenplay was published in their annual fiction issue. Entitled, “Scenes of the Crime,” these few yet dense pages detail McCarthy’s eye for exhilarating action and crisp mise en scène. The excerpt follows the maneuvers of the key-lime green motorcycle seen in the trailer. Most notably, his vivid and climactic leap across the screen:

SHOT OF THE green rider with his face turned back to the floodlight, which is now behind him. Suddenly, his head zips away and, in the helmet, goes bouncing down the highway behind the bike. The bike continues on, the motor slows and dies to silence, and in the distance we see a long slither of sparks recede into the dark.

The excerpt published in The New Yorker contains no dialogue. Yet, it is not absent of sounds. Temporarily removing the human element of speech enhances the impact each and every other sound makes. Quite similarly to the previous films McCarthy’s worked and written for, the voids are what stand out most saliently.

The excerpt published in The New Yorker contains no dialogue. Yet, it is not absent of sounds. Temporarily removing the human element of speech enhances the impact each and every other sound makes. Quite similarly to the previous films McCarthy’s worked and written for, the voids are what stand out most saliently.

Much is unspoken in a McCarthy novel or screenplay. The quiet, unsaid things that many other writers and screenwriters would jump at and embolden for effect are notably absent in McCarthy’s work. It may be a trademark of his—an example of the mastery he has over emotion, drama, and image. To get a sense of what the silences of a McCarthy film, one scene in particular comes to mind. The moment occurs in No Country for Old Men, were Anton Chirguh, played by Javier Bardem, sadistically harangues an unsuspecting gas-station owner in a general goods store, berating him with questions, trying to figure out if the man with many lonely aspects typical to middle-of-the-road folks, will be his next victim. The general goods store man looks at Chirguh with wide and blue eyes, and the viewer wonders if he knows that he’s falling victim to this murder’s methods. Behind the man, there are ropes for sale that are hung in loops. Yet, in this moment they suggests many small nooses, drawing the connection between death’s looming presence and the man’s earthly occupation as a purveyor of consumer products into one.

Yet, what captivated me upon watching this scene was the way Chirguh crushes the wrapper of the peanuts he was crunching on and lets it twist and unravel while never breaking eye-contact with the shook looking man. The wrapper is viewed by the man and increasingly, by the camera, which looks ignobly upon it as the wrapper writhes back into a shallowly uniform shape. This scene captures the film’s essence. In the tortured wrapper, we experience the tortures of Chirguh’s pathology—the pathology of a serial killer.

McCarthy utilizes these consuming silences again in The Counselor. And in many instances too. Yet, unlike in previous work, The Counselor is marked by a sense of thrill and delirium that surrounds those involved in cocaine trafficking. For the screenplay for The Counselor, McCarthy impressively employs his evocative writerly talents while inhabiting the many minds of characters whose lust for the best of life’s vices: lawlessness, sex, money, and power, is done with a surfeit of deft credibility.

After examining the trailer and “Scenes of the Crime,” these two glimpses into The Counselor will assure audiences that McCarthy’s descriptions, dialogue, and details will become an excellent vision on the silver screen. While he is an exceptional novelist, one with a knack for cinematic thinking and precision for the technical aspects crucial to a good screenplay, do other novelists hold to the same standard when plying their trade in Hollywood? Do the landscapes of creative work—of creating figurative and imaginative worlds, characters, and plots—relay unto the confines and deadlines of screenwriting? Here is a look at the novelist as screenwriter.

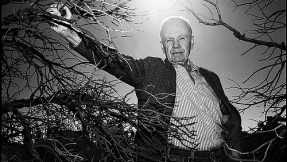

William Faulkner and The Big Sleep

Widely considered a seminal film within the history of movies, the screenplay for The Big Sleep was written in part by novelist William Faulkner. While the 1946 film had many big names attached to it: Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall in the lead roles, Howard Hawks directing, and the whole deal based off of a Raymond Chandler novel of the same name, no star was brighter, nor would burn longer, than Faulkner’s. Among the many talents involved in The Big Sleep, the dramatics, film noir mise en scène, and poignant yet colloquial dialogue, were all the more effectively rendered due to William Faulkner’s verve as a writer.

Along with Ernest Hemingway, William Faulkner is foremost on the list of great writers of the modern era. Yet, he found himself in Hollywood out of necessity, not desire. Faulkner was broke, and while his novels were kept in circulation do to warm reviews, they were not selling well enough for him to support his large family. Faulkner aimed to ameliorate his troubles in Hollywood. He left his home in Oxford, Mississippi to abate his financial worries while attempting to support his infamous ego. While it would be another decade before he would receive a Nobel Peace Prize for Literature, his self-image as a superior writer, was already eating away at himself. He wanted the laurels of greatness now and for the magnitude of his talents to be every man’s envy. Yet, despite himself, screen writing was not the easiest road to travel in order to become a part of the American cultural canon.

At the time, writers who worked for Hollywood were still considered somewhat of a hack, prostituting their art for the strictures of the industry and the big bucks that comes with easy fame. Yet, Faulkner’s incredible ability for creating narratives and characters so intricate and distinct as to assume forms that transcended the words that created them–of becoming individuals, with shadows and selves–like those he wrought in Light In August or in the potboiler Sanctuary, did not make him invaluable in Hollywood. Faulkner leaned heavily on his figurative texts and his recursive story arcs. Rather than propel him to new celebratory heights, his attempt to write for the movies failed to mesh with the technical framing and quick dramatic action of Hollywood films.

Faulkner may have been a part of the team behind one of the greatest films of all-time, but what he really managed to accomplish was to pay his bills. For him, nothing so germane like As I Lay Dying could ever translate onto film. That is, until James Franco mistook Faulkner’s most perfectly calibrated text, where every word is the exact and necessary one, as fodder for another gapping look at the American South.

Faulkner may have been a part of the team behind one of the greatest films of all-time, but what he really managed to accomplish was to pay his bills. For him, nothing so germane like As I Lay Dying could ever translate onto film. That is, until James Franco mistook Faulkner’s most perfectly calibrated text, where every word is the exact and necessary one, as fodder for another gapping look at the American South.

For the cinephile in you, Faulkner’s desperation and drunkenness, were the inspiration behind much of the Coen brother’s Barton Fink (1991), especially that of the addled Southern Gentleman character, W. P. Mayhew.

Dave Eggers and Promised Land

The writer as activist. Political writing. However you want to phrase it, Dave Eggers writes stories that weave the issues of our time into settings, characters, and scenarios that are capable of connecting with audiences. Despite the global market for his work, Eggers can make audiences feel alive, enraptured in the art of storytelling, like they used to be as children. And the effect of his works is usually well wrought. However, Promised Land (2012) is not quite as deep, as interwoven a narrative of memoir and critique as A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius and What is the What are. In fact, it debuted to mixed reviews. Some found that the story could have dug further, really gotten past the politics and platitudes for and against Hydro Fracking. Or that, John Krasinski and Matt Damon did not fully realize their characters. Some critics seem to just plain out dislike Gus van Sant, who directed the film.

While Promised Land managed to be touching and heartfelt at times, the film did not fully convey the poignancy of Eggers’ gambit. The film is something else. For once, Eggers chose to widen his lens and show us a world rather distant than the micro-universes his tales usually revolve in. Rural Pennsylvania has not seemed so distant and real until Eggers took us there. Yet, the film was not as involved, not so elliptical as Eggers’ writing. It lacked his distinct voice and humor that evoke something deeply personal in viewers, as if our best friend were telling us his story at the right time and the right place.

Eggers imparts a precious quality to his work that has made him unique and successful. However, as talented and driven as Eggers may be as a writer, activist, and philanthropist, his knack as a post-modernist does not always carry over successfully with audiences when it comes to his screenplays. For instance, some people still haven’t been able to digest the stilted retelling of Where the Wild Things Are (2009) that he wrote the screenplay for. So, perhaps it’s not the politics that’s making people uncomfortable.

Eggers imparts a precious quality to his work that has made him unique and successful. However, as talented and driven as Eggers may be as a writer, activist, and philanthropist, his knack as a post-modernist does not always carry over successfully with audiences when it comes to his screenplays. For instance, some people still haven’t been able to digest the stilted retelling of Where the Wild Things Are (2009) that he wrote the screenplay for. So, perhaps it’s not the politics that’s making people uncomfortable.

Michael Chabon’s Flummoxes

Hailed as one of the most important and successful writers of our time, Michael Chabon is the author of the books The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay, The Mysteries of Pittsburgh, and The Yiddish Policemen’s Union among many other works. Yet, for a man of such wit, veracity, and astonishing ability to produce quality literature relatively quickly, Chabon has yet been able to flourish in Hollywood. Or, at the very least, Chabon has yet to explode like so many spectacular and damned near fatal rockets in the film industry as fans of his writing may suspect. While some of his books have been adapted into feature films, including, Wonder Boys (2000) and The Mysteries of Pittsburgh (2008), unlike his fellow literary luminaries such as Paul Auster and Sam Shepard, Chabon has struggled over the years, unable to bring a screenplay to fruition that resounds as well as his books do.

Fans of Chabon are quick to quote his love of genre fiction, that of superheroes and comic books in particular. And they are right to do so. No other American literary figure has done as much work to make the cape crusader a cool, albeit, vaguely bookish, kin to the rest of literature’s family of Holden Caulfields and Henry Perownes. Yet, his forays into the superhero movie business have resulted in rejections and half-born out of the ashes, half into oblivion, screenwriter credits on films such as John Carter (2012) and Spiderman 2 (2004).

Fans of Chabon are quick to quote his love of genre fiction, that of superheroes and comic books in particular. And they are right to do so. No other American literary figure has done as much work to make the cape crusader a cool, albeit, vaguely bookish, kin to the rest of literature’s family of Holden Caulfields and Henry Perownes. Yet, his forays into the superhero movie business have resulted in rejections and half-born out of the ashes, half into oblivion, screenwriter credits on films such as John Carter (2012) and Spiderman 2 (2004).

In his defense, Chabon cites his “pre-emptive cynicism” for his flummoxes in the business. A mixture of too pragmatic audiences coupled with studio executives who lack the gene for open-mindedness are what seemingly beset Chabon’s woes. Yet, if equally as lauded, talented, and productive writers can write screenplays for the big Hollywood machine, Chabon’s inability to get a superhero treatment that lifts the roof beams off of the proverbial movie-set rafters produced, is a sign that even the mighty giants of literature stumble among the hills of Hollywood from time to time.

Bret Easton Ellis and The Canyons

Writers go to Hollywood for several reasons. Some go for money, for the lurid enticements of fame, some go to ensure that the integrity of their adapted work is not botched, and some go out of the love of film even. And successful writers go for much the same reasons that the nominal writer does. Yet, what about the darker films? Those were blood is shed and it does not look like melted Crayola 64-packs? What about the films were the sex is portrayed as a nasty and hot affair? Something grand like Titanic yet not so eccentric as to be another Eraserhead? In a word, cinematic. Bret Easton Ellis writes those kind of screenplays. Famous for penning American Psycho (2000) and The Rules of Attraction (2002), Easton Ellis has brought his most recent tale of lust and self-destruction to the big screen in The Canyons (2013).

This film borrows many of the best elements of Easton Ellis’ novels to great effect in this Paul Schrader directed film. The intensity of well-poised dialogue and the heat of dramatic couplings is turned into a gripping tale of mind games and bloodlust in The Canyons. Yet, what this film is on another level, is exceedingly familiar to both screenwriters and novelists alike: the meta-representation of the writer’s world. Over and against the winning elements Easton Ellis brings to this film, The Canyons is a movie about movies. The film portrays a version of Hollywood that is not totally familiar yet somehow recognizable, if not only from the memories it stirs in the viewer.

This film borrows many of the best elements of Easton Ellis’ novels to great effect in this Paul Schrader directed film. The intensity of well-poised dialogue and the heat of dramatic couplings is turned into a gripping tale of mind games and bloodlust in The Canyons. Yet, what this film is on another level, is exceedingly familiar to both screenwriters and novelists alike: the meta-representation of the writer’s world. Over and against the winning elements Easton Ellis brings to this film, The Canyons is a movie about movies. The film portrays a version of Hollywood that is not totally familiar yet somehow recognizable, if not only from the memories it stirs in the viewer.

We used to go see, or at least our older siblings used to go see the genre films The Canyons references. Those deserts, the way the actresses look, they are of a type, a Hollywood type. Writers try and try again to tell us what they know. So, it comes not as a shock but a tap in the gut to see that the novelist writing in Hollywood will write about the machinations of the movie industry.

Easton Ellis’ special draw as a writer is that his tales do not seem to pause or reflect, instead, they are robust with flair. Writing about a many-layered world that is constantly aware of its self-image, Ellis’ take on the sometimes dangerous world of Hollywood decadently unravels, revealing the stark coupling between the tremendous highs and shadowy lows of show business.

What of the Novelist in Hollywood?

While I only surveyed the list of novelists who moved west, wrote (and more often, attempted to write) screenplays for the big screen, there is still much yet left to discuss and uncover. I consider myself somewhat like a neophyte astronomer, gazing into the sky and immediately recognizing first the biggest and brightest stars, shouting out, “Here, look at them all!” That being said, the writers left to examine yet are manifold. But that is not where this article will drift. Instead, I consider that by looking back at Faulkner’s, Eggers’, Chabon’s, and Easton Ellis’ times in Hollywood, while keeping an eye ahead, towards the future of films, McCarthy and The Counselor are put into conversation with a rich tradition of highs, lows, successes, and failures—the whole deal. Further, it is worth keeping in mind that all of the aforementioned writers are no ink-stained wretches either. These men are some of the most gifted of their trade. Yet, they seem to lack what McCarthy culls time and time again: great panache for the mores of Hollywood feature films. Absent too, are any discussions of female writers or writers of color. Their tales will be given the full extent of analysis and study that they deserve, but in due time.

For now, let’s retrain our sights on Cormac McCarthy and The Counselor. Later on in the screenplay for The Counselor is a short description of a man, punctured by a bullet, sitting on a sofa, carefully bleeding out:

A MOBILE HOME at the edge of the junk yard. Interior. The wounded man is lying on a cheap sofa, with his leg stretched out on a coffee table that is covered with a sheet. There is a plastic bucket on the floor filled with bloody gauze.

Scenes like this are liberally peppered throughout “Scenes of The Crime,” which means that we can dream for now, and expect the story of the bleeding drug trafficker to resume this autumn. While only a few pages were published, the rest of the screenplay promises to be even more captivating. And because Cormac McCarthy wrote it, the screenplay does not bar any pretenses to be less riveting than the scenarios related in “Scenes of the Crime”. The Counselor may be McCarthy’s most enterprising work to date. It looks to be more thrilling where The Road was ghastly. High-octane where No Country for Old Men had a funereal tread.

Scenes like this are liberally peppered throughout “Scenes of The Crime,” which means that we can dream for now, and expect the story of the bleeding drug trafficker to resume this autumn. While only a few pages were published, the rest of the screenplay promises to be even more captivating. And because Cormac McCarthy wrote it, the screenplay does not bar any pretenses to be less riveting than the scenarios related in “Scenes of the Crime”. The Counselor may be McCarthy’s most enterprising work to date. It looks to be more thrilling where The Road was ghastly. High-octane where No Country for Old Men had a funereal tread.

Looking at the trailer for The Counselor again, we can be sure to expect a great film. One that combines the throes of literary creative endeavors with the precision and illumination of motion pictures.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

I’ve read the screenplay and it’s a fascinating and very unconventional screenplay, and it’s perfectly fitting yet a very stark difference in McCarthy’s catalogue. I really liked it and believe it will make a very fine movie, but the third act was very frustrating. I know that it works for the themes of the story, but iit’s even more challenging and infuriating than No Country For Old Men in it’s introducing of new characters and lack of focus on who we thought the main character actually was, and the sort of heartless disposal of characters we become invested in. It’s really going to piss some people off… But that’s probably a good thing.

I came across a copy too. I think it’s written to be adapted for the screen. Well, all screenplays are but this one’s got a lot of details and good pacing. It’s also got sudden bursts of violence and dark stuff. McCarthy has a vision and I see him playing a vital role on the sets and in filming. I found it slightly dull but I’m damn sure Dariusz Wolski will fix that.

I’ve watched the 2 trailers and no story seems to emerge from that. I found this article very insightful, thanks.

Well, I have yet to see anything by Bret Easton Ellis that is worth more than a pile of dog manure. Certainly not “American Psycho”, nor “Less Than Zero”, both books that, academically speaking, are garbage. I should know, I graduated with distinction in American literature. 🙂

Scott’s a very overrated director in general he only really has two truly great films (obviously Blade Runner + Alien) and he let it get to his head with a career of relatively by the numbers films after. Hopefully he breaks the trend on this one.

I always think of Stevie Wonder. From the late 60s to the mid 80s, Stevie’s faucet runneth over. The genius was at his zenith of creativity. I guess one can only sustain that level of brilliance for so long. He’s still amazing but nothing can match his golden years. Probably not the greatest example but his name popped in my head when I thought about Ridley Scott. I guess we can’t expect an artist to sustain that level of creativity throughout their career. If they can, great.

Cronenberg is making me sad these days but I’m still a fan. I’ll give Scott another chance but I won’t forgive him for Lindelof.

If I had one wish, I would replace Scott with Michael Mann. Imagine it.

This definitely has the potential to show the complexities of the characters and humanity as a whole, but it could also derail and go in a totally goofy direction. I think it all depends on how well Scott deals with McCarthy’s decision to write Cameron Diaz’s character as a Trill. Of course it’s not like Ridley doesn’t have sci-fi experience, so I’m not too worried.

Fantastic article! I loved Chabon’s Kavalier and Clay, which was supposed to be made into a film very shortly after its publication. I recently read a summary of his screenplay for it and was really disappointed with its lack of respect for the source material; someone commented that he just isn’t at all precious enough about his own work.

Thanks for reading the article, Amelia.

I agree, Kavelier and Clay is one of the best books I’ve ever read. Yet, Chabon approaches Hollywood with more reproach and skepticism than most other writers would. It’s unfortunate. It’d surely be a benefit to see an original screenplay of his on the big screen.

Speaking of preciousness, have you read his article on Wes Anderson that he wrote for the New York Review of Books? Now, what a collaboration that would be!

Yes! It would be absolutely incredible.

Bret Easton Ellis did not write the screenplay for either American Psycho or Rules of Attraction.

Bret Easton Ellis’s surname is Ellis.

I truly think Sir Ridley will handle this very well. Most of his duds were because of not very well written scripts. I believe that Sir Ridley has been dying to adapt a Cormac McCarthy novel(Blood Meridian) for a long time so I think he will do McCarthy justice. It’s an interesting choice for him because it’s so minimalistic compared to the usual Ridley Scott epics that everyone expects from him.

Also this is kinda sad to say but I think with the death of his brother Tony, Sir Ridley might relish in the very bleak tone of this film and not shorthand anything.

nice article. Cormac is my favorite author and The Counselor is one of my favorite books, so I’m prettttty excited for the film.

Charles Bukowski is a very interesting case of novelist-turned-screenwriter, particularly as we have a novelised account of the making of ‘Barfly’ in Bukowski’s ‘Hollywood’.

Great article! I honestly hated the counsellor, which was such a shame because Ridley Scott + Cormac McCarthy + heaps of great actors SHOULD theoretically lead to a good film!!! Nevertheless, I was significantly underwhelmed and left very very confused (which I believe was the general consensus)

I have read excerpts from the screenplay, and Cormac’s writing is beautiful (to say the least). So where did it fault?! Casting? Directing? Or was it just simply that Cormac’s writing failed to transfer well to the screen? The storyline was vague and consisted mainly of action scenes intertwined with deep and meaningful monologues about greed and death…. not a good watch.

I love all the elements that went in to creating The Counsellor, I’m very surprised it was so underwhelming.

I loved the Counselor, but I feel like I might be the only one…

McCarthy’s great strength is his ability to construct concurrent realities, and crash them into each other… Everyone secretly hopes the world has a bottom, a limit, that certain unthinkable horrors should never be allowed to occur simply because they are unthinkable. We construct lives within this belief and let the passing years convince us that the unspoken contract we hold with life – that we will be spared horror – is binding, or resonates with something beyond our own desperate desire. The Counselor, to me, epitomizes McCarthy’s ability to both articulate and destroy this illusion. Absolutely masterful execution. I can’t wait to watch it again.