“A Bout de Souffle” by Jean-Luc Godard: How Did It Reinvent Modern Cinema?

During the 1950’s, the popularity of French cinema had gravely declined. It was in need of renewing itself but it had not yet succeeded. In 1960, when Jean-Luc Godard’s first full-length feature, A Bout de Souffle (also known as: Breathless), premiered in cinemas, it ignited an uproar. The film conquered audiences and critics and initiated the movement of la Nouvelle Vague (the New Wave) alongside François Truffaut with 400 Blows and Alain Resnais with Hiroshima Mon Amour. These films greatly affected and influenced the cultural scene during the sixties and has continued to influence it today.

A Bout de Souffle illustrates the theory and practices of the New Wave. To describe this movement, one could simply refer to Vivre sa vie by Godard, when a girl said: “The story is stupid, but it’s really well written.” In 1957, Françoise Giroud in the newspaper L’Express, gave this name to a new generation of filmmakers (all former critics of the Cahiers du Cinéma). The group called themselves a “band of outsiders” and they were united by their contempt of the ‘tradition de qualité’ which dominated the film industry at that time. The quality of French films became trapped in a standard which lacked imagination and tried to copy the Hollywood norms. The critics of the Cahiers du Cinéma were tired of this old fashioned style and wanted to bring the spirit of the youth back to films.

A Bout de Souffle and the ‘Death of Cinema’

Godard declared that, “A Bout de Souffle is a story, not a theme.” The film does not have a theme as it incorporates several genres like crime, comedy and love. At first, it presents itself like a typical detective film. Michel Poiccard (Jean-Paul Belmondo) stole a car in Marseille, then killed the cop who followed him. He escapes to Paris and tries to run away to Italy with Patricia (Jean Seberg), an American expatriate, who he says he’s in love with. However, due to threats by the police, Patricia tells on him and he is killed. The film never stays true to one genre. It has an erratic nature because Godard filmed it without a complete script. With a general storyline, during the four weeks of principal photography, he constructed the film from day to day. “It’s not improvisation,” he said. “It’s decision-making at the last minute.”

During the first part of the film in Marseille, several elements of spontaneity can be found in the film. At first glance, it evokes the film noir. A Bout de Souffle begins with a close-up of Poiccard who is wearing typical gangster clothes and has a cigarette between his lips. When he steals the car, Poiccard abandons his female accomplice to the crime. All these elements are classic of detective films. However, there is a sudden stark separation with this typical Hollywood style during the sequence on the Nationale 7, when Michel is fleeing Marseille in the stolen car. The scene is full of jump cuts which gives it an accidental effect, disturbing the spatial and temporal continuity. When Michel shoots the policeman, instead of using close-ups of their faces to bring emotion, Godard filmed close-ups of the gun. This technique makes the policeman’s death impersonal because we never see his face. Furthermore, Michel and the policeman never appear in a single frame together. Michel is presented like a man who breaks the rules as he wants, and this image also represents Godard.

What is more striking, during the National 7 sequence, Michel speaks directly to the audience:

MICHEL: “If you don’t like the sea, if you don’t like the mountains, if you don’t like the city, go fuck yourselves!”

Godard draws attention to the artifice of cinema because he breaks the cinematic tradition that it must create the illusion of reality. Michel mocks the audience and they become aware of the pretence that is cinema. It seems that his speech to the audience does not serve to the development of the plot but it can be said that this awareness of the pretence satirises the classic Hollywood editing. According to Godard, “A Bout de Souffle was the type of film where all was permitted, it was in its nature.”

Godard began his career as a critic, his vast knowledge of films allowed him to remake the classic Hollywood style and to use references to American cinema which provided an elaborate intertextuality. Godard did not hesitate to display his influences. The film is dedicated to the American producers of series B gangsters (low budget commercial films). Its biggest reference is of Humphrey Bogart. Throughout the film’s entirety, Belmondo raises his finger to his lips and this tic pays homage to detective films, made famous by Humphrey Bogart in The Maltese Falcon. This obvious reference satirises Hollywood and brings an air of comedy.

Many critics consider the end of A Bout de Souffle as ‘mythical’. Poiccard tried to escape the police, but he is struck down with a bullet in his back. He stumbles along la rue Campagne Première and mutters before dying:

MICHEL: “It is really disgusting!”

PATRICIA: “What did he say?”

A POLICEMAN: “He said that you’re really disgusting.”

PATRICIA: “What does ‘disgusting’ mean?”

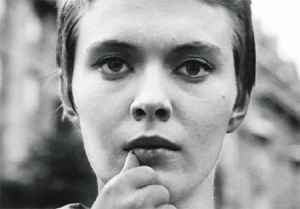

This scene pays homage to High Sierra, when Ida Lupino asks Humphrey Bogart before he dies, “What does it mean… when a man ‘crashes out’?” Furthemore, Patricia turns to face the camera and lifts her finger to her lips in reference to Michel’s tic which is inspired by Bogart. In differentiating and satirising Hollywood conventions, A Bout de Souffle ends in ambiguity. The film never resolves what ‘disgusting’ means. Does the word signify Patricia’s betrayal or Michel’s death? This introduces two themes: the role of woman and death.

Before filming A Bout de Souffle, Jean Luc Godard suffered a period of depression. He wanted to make a film “of a boy who thinks of death and of a girl who does not.” The subject of death is present from the beginning of the film. The first frame is of a woman on a newspaper, predicting Poiccard’s death at the hand of Patricia. Later in the film, Michel asks her, “Do you ever think of death? I never stop thinking of it.” Since Godard wanted to reinvent cinema, it can be said that A Bout de Souffle is the metaphorical ‘death of cinema’. In his opinion:

“Cinema is the only art which, following Cocteau’s phrase (in Orphée, I believe), ‘films death at work.’ The person being filmed is in the process of ageing and dying. We therefore film a moment of death at work. Painting is motionless, cinema is interesting because it seizes life and the mortal side of life.”

The inherent relation between death and ageing has a link to the theme of time. Poiccard is always asking what time it is, which demonstrates his obsession with death and his mortality. Moreover, the general fast-paced editing, with his heavy use of jump cuts, reflects the imminence of death and Michel’s race against time.

To come back to the idea of ‘death of cinema’, “we find these two poles in documentary and fiction.” The two methods combined of using handheld camera and on-location filming produce an unexpected effect of a documentary in a story of fiction. This documentary style makes the film more authentic and realistic. The filmmaker opens his audience to a new world of “an unforeseen form of naturalism.” The overall rapid rhythm of the film slows down during the ‘household lover’s scene’. At 24 minutes long, it makes up nearly a third of the film. This scene, which displays ‘naturalism’, was a new invention providing the audience with an impression of realism. It’s an intimate scene which is evident through the spontaneity present in the mise-en-scène and the dialogue. The scene is scattered with the comings and goings of the two characters during which their conversation spans from literature to Michel’s desire to sleep with Patricia. With the alternating camera movements, it underlines the difference and misunderstandings between man and woman.

The ‘household lover’s scene’ does not only represent the realism of modern lovers but also demonstrates the evolution of changing relations between man and woman. This opens up the examination of the role of woman in A Bout de Souffle. The scene presents a mix of wide frames of the two characters together, with close ups of their faces, and tracking shots which follow Michel and Patricia around the hotel room. The oscillation of different frames show the changing values of woman in society at that time. The scene pivots between Michel and Patricia: Michel who wants to sleep with her and her resistance before giving in to his advances. However, the reason for which she says no at first and later changes her mind is never evident.

Although Patricia embodies the female stereotype with her romantic ideals, “I want us to be like Romeo and Juliet”, she is hesitant and unsure of what she wants to do and if she loves him. Her career as a journalist is still a priority. In the scene where Patricia joins other journalists to interview a famous writer, Parvulesco, a question is posed:

A JOURNALIST: “Who is the most moral: a man who abandons or a woman who betrays?”

PARVULESCO: “The woman who betrays.”

This prediction of Patricia’s betrayal whilst she is pursuing her professional ambitions illustrates her role as a femme fatale in the genre of a classic film noir. Although at the same time, it underlines her inner conflict between love and a career. During Parvulesco’s interview, he reduces her ambitions to nothing but that she’ll be a pretty woman and Patricia smiles in return. When he finally responds to her question, we see a close up of her face which looks directly to the camera and this predicts the end of the film. Her imitation of Michel gives ambiguity and provokes the conventions between the role of men and women in films noirs. Although Patricia realises the role of the femme fatale at the end of the film, she disrupts the conventional role of woman at that time.

A Bout de Souffle and its Impact

It is difficult to imagine the history of cinema without A Bout de Souffle. The film had a profound effect, after its release and still today. After the birth of the New Wave, between the years 1959 and 1960, the number of entries of film increased in millions. Furthermore, there was a regular and rapid increase of investment in film until the 1980s. A Bout de Souffle was filmed on location which reduced the studio expenses and was filmed without expensive, famous actors. Godard showed that filming was possible for anyone. He inspired young people and encouraged them to make their own films – even at a small budget.

Through A Bout de Souffle, the filmmaker influenced directors of the sixties and beyond to think of new ways to make and think of films. Today, he has influenced directors such as Lars Von Trier and Quentin Tarantino. Like Godard, they have a tendency of breaking the conventional boundaries of cinema. Lars Von Trier was inspired by Godard when he started the movement of the Dogme 95 with fellow Danish director Thomas Vinterberg. In parallel to the New Wave, Dogme 95 inspired filmmakers to gain recognition not through big Hollywood budgets or famous actors but through quality. Characteristics of the Dogme 95 reflect elements of Godard’s work as shooting was done on-location and through the hand-held cameras. It also demanded only diegetic sound and special effects were forbidden. All this was done to incite the reimagination of cinema. With Quentin Tarantino, his production company, A Band Apart, was named after Godard’s film Bande à Part. His films are recognisable through their parodies of stereotypical characters and stories which are similar to those of the series B thrillers. David Denby, in his review of Pulp Fiction, explained:

“Pulp Fiction is play, a commentary on old movies. Tarantino works with trash, and by analyzing, criticizing, and formalizing it, he emerges with something new, just as Godard made a lyrical work of art in Breathless out of his memories of casually crappy American B-movies. Of course Godard was, and is, a Swiss-Parisian intellectual, and the tonalities of his work are drier, more cerebral. Pulp Fiction, by contrast, displays an entertainer’s talent for luridness.”

Tarantino’s films experience a post-modern self-consciousness, forcing the audience to be aware that they are watching a movie, just as Godard did in A Bout de Souffle. For example, in Pulp Fiction, Mia draws a rectangle when telling Vincent to not be a ‘square’, and this was visually highlighted as Tarantino added white dashes on the screen. This unexpected visual effect of the rectangle breaks the illusion of realism in cinema. Also heavily featured in Tarantino’s films is intertexuality, with Pulp Fiction making references to films like Psycho, A Clockwork Orange and The Seven Year Itch. Through the unconventional deconstruction and reworking of popular Hollywood genres, Godard inspired filmmakers to provide an escape from the banality of cinema.

“I love A Bout de Souffle enormously, but now I see where it belongs – along with Alice in Wonderland. I thought it was Scarface,” Godard admitted. This statement reflects his attitude and lack of preoccupation with categorising the film. A Bout de Souffle is the first ‘post-modern documentary’ of the aspirations of the filmmakers of the Cahiers du Cinéma and of what they wanted to accomplish through the New Wave. Although it reflects the traditions of the film noir, it reversed its conventions through satire and parody. Godard said, “What I wanted, was to depart from a conventional story and remake it, but differently, everything that cinema had already done.” The director deliberately incorporated elements of comedy in the gangster narrative to encourage filmmakers to renew the production of cinema. “A categorically obvious departure from all the technical rules, an evident taste for provocation, drove Jean-Luc Godard to reinvent cinema,” emphasised Jacques Siclier. We can not identify ‘the theme’ of A Bout de Souffle, with its documentary style in a story of fiction. The filmmaker showed us the unlimited functions of cinema and the metaphorical ‘death’ of how cinema had once been.

Works cited

Fotiade, R., À bout de souffle, (I.B. Tauris & Co Ltd, 2013)

Godard, J.-L., Jean-Luc Godard par Jean-Luc Godard (Cahiers du Cinéma/Étoile, 1985)

Siclier, J., Nouvelle Vague ? (Les Editions Du Cerf, 1961)

What do you think? Leave a comment.

I watched this for the first time this week in my film studies course (I’m a musician, but I love movies and I’m doing this course for fun!)

I found it interesting, but not easy to get used to. It’s the first French New Wave film I have seen, I’m finding the learning curve quite steep. However, despite the apparent lack of plot, I enjoyed it. I loved the interaction between the two protagonists and felt the dialogue (admittedly in English translation; I don’t speak French very well) was sharp and witty. I also liked the camera-work, which made the whole thing seem very real, as if a chunk of real life was simply being recorded as it happened by somebody with a camcorder. Despite this superficial “reality”, however, there was clearly a deeper artistic level which I have yet to penetrate! I look forward to seeing it again.

The first time I saw A Bout de Souffle, I was just dipping my toes into the French new-wave, and it was my first Godard film. I was put off by what I thought was overtly ‘Frenchy’ types of attitudes by some characters, mostly by the lead in Belmondo’s performance. But I had admiration for the craft of the film- the editing and shots extraordinary at times- and as I’ve seen it again I think it’s better than the B grade I gave it a year ago. I don’t think it’s one of the best Godard films I’ve seen (Alphaville, My Life to Live, and Band a parte take those positions), but it’s an important film to be seen by film buffs, for better or worse for the viewer.

I saw this as a parody of the noir genre. The long conversations about nothing, the jumpy editing was funny for me, etc. I thought it as an excellent movie and understand its context, but I saw the whole thing as satire.

This film was not worth wasting time on, being merely a historical artifact for film theoreticians to foam over and immaculate.

Don’t get me wrong, some of my favorite films are from that period — 8-1/2, La Dolce Vita, Jules et Jim, La’Aventura, L’eclipse, Dr. Strangelove, Bicycle Thieves, even Orphee.

So, in that context, Godard looks like a pretender, the mumblecore maestro of his time… in other words, self indulgent, crappily done and largely pointless.

I guess people must have been really desperate for entertainment in 1960…

I like your idea of Godard as a “mumblecore maestro” …I never thought about him like that haha : )

I wouldn’t say his work his pointless, though. Just as 8 1/2 is concerned with film, so are most of Godard’s features. Godard focuses on the act of film, what is film, what are characters, the physicality of film. He may seem cold at times (certainly not like Truffaut!) and inhuman, but his great films are very solid, and very different from anything mumblecore.

I think this movie is fantastic! One of the big contributors to New Wave.

Love the film noir feeling and the themes of the movie such as the ideas and perspective of American woman vs. French man or broken relationship.

One of the the most important aspects of Breathless is that along with 400 Blows and Le Beau Serge it incorporates the idea of the flaneur into film. Characters will go on long walks talking, looking, and listening. Louis Malle also introduced Jeanne Moreau to the world in a similar fashion a few years earlier in Elevator to The Gallows

Griffith popularized montage. That is linking shots together to make a sequence instead of shooting an entire scene in one shot. In fact, his movies are the opposite of jump cuts as his movies attempt to make te editing invisible (as has become the standard Hollywood style).

When I first saw it, I loved the movie in little pieces (such as bits of dialogue) but not as a whole, narrative structure. It was also my first Godard film and my second New Wave film (the first was Truffaut’s Jules et Jim, which I LOVE). However, I just saw My Life to Live and I thought it was a masterpiece, mostly because although people praise the quick, spontaneous feel to Breathless, My Life to Live felt that it was more planned out and not like Godard was just making it up as he went along.

I thought Godard’s main influence was the “up close and personal” feel to his movies, namely this movie. The hand held cameras, dodging in between characters, following them through city streets etc. I’ve always thought that the “New-wavers” birthed a sort of freedom in film making. No scene in this looks staged, or unauthentic like most American films of the time. It is all on location, fluid and free. I know the use of jump cuts was influential to a degree, but I thought that was a more minor technique in Godard’s films.

I find it interesting that you bring Tarantino in the conversation of influence in reference to Godard’s work. I had never really considered the two of them to be in similar veins, mainly because of the sheer difference of scale between the works of the two. Godard tries to show the rich workings of the inner lives of his characters by giving the audience little to reflect on in the terms of the plots of his works, instead choosing to focus in on the interactions of the very “real” seeming people in his films. While Tarantino gives an almost opposite effect by completely exploding the actions of his characters across the screen through the use of extreme violence and the heavy use of one-liner-esque dialogue which makes the characters almost parodies of real human beings. But upon reading this I find it hard to ignore the fact that Tarantino’s post-modernist leanings most likely find their origins in the New Wave. Very thought provoking article. Good work.

Woody Allen clearly had a fixation on his work, Annie Hall often feels like a comedic A bout de souffle. And Allen influenced everyone. The whole framing of characters standing in the street and moving around a city is especially influential.

I definitely agree, reading this article after re-watching Annie Hall recently helped me see more of the connections. Godard and Allen, two ground-breakers, in love with the art of cinema, that’s for sure.

I saw this movie in French class, and your analysis really helped me see more in the film than I did before. I was especially interested in the connections your analysis provided with death and the woman/femme fatale.