Tolkien’s Art and Politics: Is Middle-earth Real?

The world of Middle-earth is real.

Professor JRR Tolkien created a work of literature which has highly developed cultures with workable languages and complex political/social organizations. It also includes an expansive geography populated by forests, marshes and mountains which animate the narrative and help complete the visitor’s entrance to this secondary world. His artistic creations featuring Middle-earth, through his published visual art and narratives, have received extensive critical and public acclaim, especially The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit. Others have documented the astounding success of these works; some have even claimed that Tolkien is the greatest English-speaking author of the 20th century (see Shippey, 2000 and Mathijs, 2006).

It is incontestable that these works has reached a wide audience and birthed a multi-billion dollar industry, but on what basis may I claim that Middle-earth is real? This thesis rests on the strength of Tolkien’s art (writing and visual) and its ability to create meaning and shape values in the mind’s eye of the reader, thus making his invented world very ‘real.’ In short, powerful visual and literary art impacts real world values/culture and can lead to the creation of political beliefs and public policy. I know this is a lot to accept, but please follow with me (if you will) as I make this case through the remainder of this essay.

Tolkien’s Visual Imagery

A legion of Tolkien scholars have attempted to dissect how his art and literature were created and what accounts for their appeal. Much attention has been paid to the design element of his work; that is, the construction of his various invented languages, the creation of maps of Middle-earth, family lineages of its characters, the etymology of its key names and the like. Others have pointed to the metaphorical and allegorical features and connect it to larger values that they suggest evoke spiritual and religious reflection (see Dickerson). Indeed, the scholarly energy applied to understanding his creative process in forming Middle-earth is remarkable; however, less attention has been paid to the Tolkien’s writing craft. I use craft here to mean the specific style, prose and ‘voice’ the author uses to frame his narrative. I argue that there is a high value in examining the presentation of Middle-earth (i.e. its design) through the scope of his literary craft in that it provides another layer for understanding the work’s appeal and opens valuable insight into the process of secondary world creation through this artistic device (see MacLeod & Smol, 2013).

Tolkien’s talents as a poet, narrative designer, philologist and visual artist (drawer and painter) were honed over a lifetime of devotion to his art; he was variously a scholar, father, husband, soldier, Catholic, teacher, artist and numerous other identities in his rich and long life. It is clear that all of these aspects of his personality contributed to some extent to the creation of his artwork, literary and visual.

While not diminishing any of these influences, I propose that his imagery is mainly activated through his skill and talent as a painter/drawer, which supplied a constant source of inspiration for his visual imagination and directly inspired his writing craft. In essence, I maintain that JRR Tolkien’s enchantment springs from his ability to employ the power of the written word with the observational skills of the visual artist. The connection of light (hence, colour) with the metaphorical use of language is used to such effect that it moves the reader to secondary belief; that is, one can feel the world Tolkien imagines, not simply have it described to us.

It has been shown elsewhere that Tolkien was a skilled drawer and painter and enjoyed a lifelong interest in making pictures (MacLeod & Smol, 2008 and Miller, 1981). It is clear that he was an accomplished visual artist; he employed a variety of techniques and mediums and rendered a wide range of subjects. His artwork was published during his lifetime and he had at least one posthumous solo exhibition. One can only imagine the prices his artwork would command if they were available in the market today.

“In the style of’” for a visual artist may describe artistic content and link it to an artistic movement or ‘ism’, but just as likely it could be a commentary on the artist’s technique or craft. Using the theoretical paradigms associated with the visual arts can provide insight into his drawings/paintings and it can also comment on the form of his writing style. Therefore, I argue that Tolkien’s painting and drawing technique (and his writing technique or craft) can be described in terms of an artistic movement, such as: Impressionism, romanticism, medievalism and pre-Raphaelitism. As Hammond and Scull note Tolkien’s artwork has been described as “Post-Impressionist, Expressionist, even a cubist!” (Hammond and Scull, p. 11) I go further and remind readers that he was a competent designer (book jackets) and calligrapher.

Tolkien’s impressionist label seems appropriate when you see his work. Hammond and Scull describe it thusly: “A simplification of natural forms and the use of flat colour for pattern effect rather than modelling” (Hammond and Scull, p. 9). I’m not sure I would describe his use of colour as flat. Rather, colour is applied loosely with visible brush strokes and bright primary colours – a hallmark of impressionist technique (Impressionism was first recognized in France between 1860 – 1900, painters such as Monet, Renoir, Morrisot, Degas, although some have argued that Impressionism is really of Italian origin).

One of the aesthetic strengths of Impressionism is that it allows room for the viewer to participate with the artist in completing the picture. Unlike a highly detailed photo, or hyper-realist painting where most everything is described for us, Impressionist work demands a different reaction from the audience - the simplified forms are more universal and the direct colour choices present a world, allowing for the possibility of the viewer to complete the details in his or her mind’s eye. In short, Tolkien’s ‘Elvish Craft’[1] dances in his expression of colour and form as an artist and writer.

On another level, it is interesting to reflect on the content of his pictorial images – that is, the combination of technique with the subject of the composition, including the values, ideas and feelings present. For me, many of his pictures evoke a spiritual and meditative quality (see MacLeod and Smol, 2008 and Hammond and Scull, 2004). Tolkien bids us enter a world of vivid colours and fantastical shapes and forms suggesting other-worldly landscapes, seascapes, creatures and people. Other than his early work, compositions drawn and painted from direct observation of nature, his formative pictures at the height of his creative power suggest a deep reflection on the afterlife and spiritual realms. I purposely separate spiritual from Christian in this context; Tolkien’s work does not seem to reference standard Christian (including Catholic)iconography. I have found no examples of Tolkien’s artwork that portrays the Biblical narrative or Catholic imagery that he no doubt would have been well familiar. Moreover, Tolkien does not present a safe, clean world of child-like naiveté – not at all; his bright palette and compositions show us beauty and despair. His use of simplified forms and colour does not mean his art is simple; rather the opposite, he presents deeply felt values and emotions that ask for a response from the viewer, like Impressionist paintings.

Some critics try to dismiss his art (and creative writing) as naive, prepubescent and sexless, perhaps a fantasy best suited for adolescents who have yet to discover their sexuality and sophisticated moral insight. I counter that’s unfair – his art and writing provide portals to deeply moving spiritual expressions of love, courage and sacrifice, every bit as satisfying to the adult mind as an artfully expressed sexual encounter.

A visual artist whose work contrasts nicely with Tolkien’s is Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio. The interesting point of comparison is that Caravaggio was hired by patrons to paint on walls and canvases to illuminate the spiritual (i.e. Catholic) world view, but often he ended up showing us visceral, bold yet base compositions of street life in 16th century Rome as Catholic iconography. His work is violent, even brutal in its portrayal of lust, greed, hate, etc. He shows us decapitations, torture and various other physical forms of assault. All of this is laden over with a heavy dose of barely veiled sexuality; indeed, painted figures (often young males) ask us (the viewer) to approach and be treated to sexual pleasure (for examples, see Franklin and Schutze, 2011).

Not only is Caravaggio’s content removed from Tolkien’s, so is his technique. Caravaggio’s scenes are carefully rendered figures placed on darkly tinted canvases, dramatically lit in chiaroscuro light (Caravaggio is credited with inventing the chiaroscuro technique). My point is that both artists can awaken equally powerful feelings in the viewer. One draws its energy from a spiritual/meditative source the other from bawdy, lusty, raw humanity. Both express beauty and ugliness.

Jeff MacLeod, acrylic on canvas.

Tolkien’s Writing Craft

The link between Tolkien’s visual art and his writing style is apparent in the techniques which effectively evoke a rich secondary world. Tolkien has variously been applauded and criticized for the amount of detail in his creative writing. However, I argue that the key to unlocking his Elvish Craft is linked to understanding his writing style and is acknowledging that specific phraseology and word choices are far from being overly detailed, in fact they are layered with ambiguity, vague suggestions of form with a simple colour palette applied in broad brush strokes (identical to his visual art, just expressed through text).

Even in his earliest published works, such as The Hobbit, his Impressionist style is evident. Consider the following examples:

“…a wide land the colour of heather and crumbling rock, with patches and slashes of grass-green and moss-green showing where water might be.” (p. 45)

“The last green had almost faded out of the grass, when they came at length to an open glade not far above the banks of the stream.” (p. 46)

The Impressionist lilt of Tolkien’s prose is fully realized in The Lord of the Rings. Indeed, so effective is his use of this technique that often close examination is required to show the opposite; overall, ambiguity and vague impressions manifest themselves in his framing of geography and characters of Middle-earth:

Geography:

“Outside everything was green and pale gold.” (FoftR, p. 135)

“…on such a morning: cool, bright and clean under a washed autumn sky of thin blue.” (FoftR, p. 135)

“…the mountains: the nearer foothills were brown and sombre; behind them stood taller shapes of grey, and behind those again were high white peaks glimmering among the clouds.” (FoftR, p. 187)

“…the sky away westward cleared, and pools of faint light, yellow and pale green, opened under the grey shores of cloud.” (FoftR, p. 387)

“…chimneys of grey weathered stone dark with ivy.” (FoftR, p. 187)

Characters:

“He [Aragorn] went forth clad only in rusty green and brown, as a ranger of the wilderness.” (FoftR, p. 279)

“…he threw back his hood, showing a shaggy head of dark hair flecked with grey and in a pale stern face a pair of keen grey eyes.” (FoftR, p. 156)

[Gandalf] “In his aged face under great snowy brows his dark eyes were set like coals that could leap suddenly into fire.”(FoftR, p. 227)

[Elrond] “His eyes were dark as the shadow of twilight, and upon it was set a circlet of silver; his eyes were grey as a clear evening, and in them was a light like the light of stars.” (FoftR, p. 227)

Again, I maintain that a careful reading shows that Tolkien’s descriptions are not overly detailed, he uses a simple palette and the viewer is left to insert the details through their mind’s eye (see Miller, 1981 and MacLeod & Smol, 2008, 2013).

Tolkien’s Political Imagery

It is worth spending some time examining how visual and writing craft (aided by design) evoke imagery, because they inform an understanding of how an image works to evoke a narrative, which in turns actives a frame (an amalgam of values). By a careful reading of the imagery evident in The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit (what Tolkien would call ‘Elvish Craft’) it is possible to draw conclusions about the use of the author’s political imagery and suggest the deeper values they activate.

The Lord of the Rings has been characterized by some as a depoliticized work, in the sense that political power in all its forms is seen as a corrupting influence, indeed, it is manifest in the Ring itself the apex of evil (Arvidson). The ‘good’ characters shun political power and strive over a thousand pages of text to unmake it (power as represented by the Ring) through an immense, if not hopeless, quest. This directly opposes the tenets of realist theory, where the very goal of the state is to achieve as much power as possible through economic and military might. This is no way the goal of the Fellowship of the Ring; this narrative is as much about a spiritual quest for the characters as it is an attempt some sort of strategic victory in the temporal world.

I argue that Tolkien’s Middle-earth is not so much depoliticized as it is asking the reader to re-consider the composition of political authority. It presents an alternative world-view to political structures that simultaneously seem familiar and utterly unrecognizable, even implausible. Moreover, the main ‘states’ and cultures in Middle-earth resist an allegorical comparison to contemporary politics. The main characters in The Fellowship of the Ring do not operate within the realm of “bounded rationality” expected of political and public policy actors of the 20th and 21st century.

Gandalf uses feelings, or his heart, to make judgments. For example, when the company becomes lost in the Mines of Moria, he does not want to take a certain tunnel because his heart warns him against that way, and it doesn’t feel right. Elrond, when selecting the composition of the Fellowship of the Ring, abandons wisdom to allow Frodo’s friends, Merry and Pippin to join the quest. Again, the main factions for good are following a different path than direct political expediency. The Istari (Gandalf) are striving to defeat the ancient devil, Sauron. The elves are suffering the ‘long defeat’ where they willingly give up their realms in Middle-earth to rejoin their kin in the undying lands and allow other races (humans) to rule. The Dunedain are the race from which Aragorn hails and they are descendant from the Numenorians who have a direct relationship with the Valar (gods of Middle-earth). Like the elves, and Istari, they are seeking a spiritual redemption from their sundering from the Valar.

The only groups and characters which resemble modern political institutions and leaders are the ‘evil’ factions: orcs, goblins, trolls, Saruman (after his fall), Sauron and his lieutenants (Ring-Wraiths). The orcs are organized into a conscripted army where they’re given numbers and are bullied by sergeants into following orders. Saruman employs his main power, his voice with soothing tones (but peppered with deception) to convince others to serve his narrow agenda. Sauron uses his all-seeing eye to maintain order in his ranks and spy on his enemies, whilst his emissaries travel Middle-earth seeking alliances; these ambassadors employ Orwellian double-speak to confuse and enslave others.

Indeed, the one ruling Ring was forged by Sauron, and it controls all of the other rings of power; it corrupts nine kings of men into becoming Sauron’s wraith-lieutenants. In short, Sauron and his allies and minions are entirely motived by greed, lust and attaining political rule through military conquest (a familiar trope to modern eyes). Moreover, Tolkien’s clear view on power is that it is a corrupting force, in the vein of Lord Acton’s assertion that “absolute power corrupts absolutely.” I agree with Shippey’s claim that Tolkien is arguing that it is not so much a king could be a good or bad, but the mere act of becoming king (or the desire) will make you corrupt. (Shippey, 2000).

I characterize the fundamental political tension in The Lord of the Rings, and to some extent in The Hobbit, as manifest in the enchantment vs. magic dichotomy. Tolkien addresses both of these concepts in his seminal essay On Fairy Stories ‘OFS’ (2001).

Enchantment can be described as the use of creative energy, academic curiosity and simple wonder to explore the world around you, with no greater motive than to experience and learn how things are on their own terms. Or, put differently, the ability to see things through another’s frame/values.

Magic, on the other hand, is the quest to seek knowledge in order to serve a desired predetermined end. Through experiments, one attempts to bend natural and human resources to achieve the objective of the hypothesis. In essence, magic allows for the alternating of the thing being studied to suit the experimenter’s purpose. It is really about trying to control the ‘other’ through study and craft to expose the subject in order for it to serve the magician’s intent.

It is clear that the elves and the White Council (wizards) embrace enchantment: elves, who are essentially immortal, achieve their insight and excellence through art-making, long study and practicing craft. Existing in harmony with nature allows them to achieve remarkable results as foresters, gardeners, makers of music, wine, poetry, etc. Indeed, they are able to create beautiful artifacts, and they allow themselves the possibility to be changed or re-created by the beauty they encounter in their environment.

Enchantment is apparent in the operation and management of the Fellowship of the Ring in its approach to power: Elrond calls for a volunteers to attempt this perilous quest, stating “…no oath or bond is laid on you to go further than you will.” (FoftR, Ch. 3, book 2 The Ring Goes South,p. 281). The Fellowship, chaired by Gandalf, debates at length whether to take the pass in the mountains or proceed through the mines of Moria. In the end, the final vote is left to one of the least qualified to judge (at that point in the story) but maybe the one with the most at stake, Frodo, the hobbit.

Aragorn shows continual humility and reluctance to use power when faced with perilous decisions. He shows mercy and compassion at every stage of the narrative, even allowing his own troops, who have lost their will, to abandon their post as they approach the Black Gate for the final battle.

Consider Gandalf: he is a powerful wizard but placed by the Valar in the body of an old man in order to constrain his angelic-like power. His role is to guide and encourage virtuous resistance, not to fight the battle himself (video games and Peter Jackson’s misreading of this character in the film version of The Lord of the Rings notwithstanding).Overall, the Fellowship of the Ring is an egalitarian and multi-ethnic association, constituted under a freely given alliance.

By contrast, Sauron and his allies are governed by a strict authoritarian hierarchy. Orcs are governed through verbal abuse and corporeal punishment (where there is a whip there is a way); Saruman employs slave-orcs he’s bred (quasi-genetic engineering) and he verbally and physically abuses his chief lieutenant, Grima Wormtongue. Sauron’s most powerful captains have had their will overthrown through magic and are bound to servitude through his cruel domination. Moreover, no tactic or strategy seems to be beyond consideration by this alliance: mass genocide, chemical weapons, and destructive sorcery are all at play. Whereas Sauron’s approach is victory at all costs, the Fellowship seeks survival, but only through virtuous means. (Shippey, 2000)

Regrettably, modern bureaucracy and military organizations tend to follow the model employed by Sauron and Saruman rather than Aragorn and Gandalf. Civil servants are expected to swear an oath not to reveal government “secrets” and to follow process and conform to corporate “mission statements”. Employees who violate these codes risk dismissal and even prison terms. Military “education” and socialization is even more humiliating, new recruits have their identity assaulted and are forced to change their appearance (uniforms and rigid hairstyles). Also, training can be abusive with drill instructors berating and yelling at recruits – techniques that would make any orc-sergeant proud.

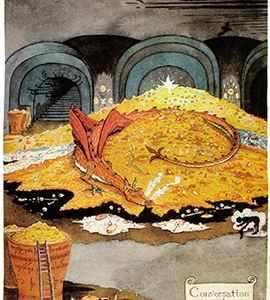

It is important to recall that Tolkien’s creative writing around Middle-earth is more of a spiritual reflection (Tolkien once described The Lord of the Rings as a Catholic work) and art-making exercise. When it strays into political imagery it is to treat naked political power as an insidious evil; it is a corrupting influence in and of itself (Tolkien occasionally refers to it as the ‘dragon sickness’; an addictive desire for wealth and power (see The Hobbit, Ch. 1). I postulate that to the contemporary political analyst, schooled in the tenets of realism, modern governance structures and the philosophy of Machiavelli, Tolkien’s reflections on political authority must seem hopelessly naive. Hierarchical structures are evident in corporate, military and governmental structures and are deemed essential to maintaining social cohesion. Accompanied by an economic system governed by the postulates of the ‘dragon sickness’ Tolkien’s voice strikes a shrill, unfamiliar chord. His critics call his work unrealistic, childish fantasy and archaic. Moreover, the genre of writing he has inspired is labeled ‘escapist’; but Tolkien himself mused as to whether it is the flight of the deserter or the escape of the prisoner? (Tolkien, OFS). What Tolkien offers us is insight into values, not a literal prescription for contemporary political organizations.

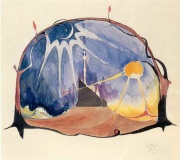

acrylic on canvas

This is my painting based on JRR Tolkien’s work.

Middle-earth is real.

It is real because it evokes a frame that allows viewers to enter its world; it affects real world beliefs and can inspire primary world political action. Indeed, the brain makes no distinction between frames activated by real or imagined imagery; therefore, the beliefs created through Middle-earth can be just as powerful as a speech delivered by a president, often more so. However, I have argued that this is not a unidirectional manifesto Tolkien is imposing on us through the ‘magic’ of his art; in fact, he offers an alternative – perhaps it can even be described as a democratic partnership, through enchantment.

This enchantment also works at a more subtle level; indeed, it is not only evident through the actions of the characters and in the design of the plot, but is expressed in the craft of the writing style and visual imagery. In essence, to express imagery is not simply a matter of what you say, it is how you say it – it is the melding of content and form. Tolkien’s style of writing and visual imagery, through the artfulness of its form, allows us an easy portal into his invented world; while we are there we are treated to his deepest reflections on spirituality, and of course, his political thought. But through enchantment, we (the visitors to Middle-earth) have some power to image, and re-image, the feeling of the whole. Thus, Middle-earth becomes in a very real sense a creation of a collective, others have taken this artwork and re-made it in ways Tolkien may not have foreseen (and likely would not have approved).

Magic in art (and science) relies on control and attempts to restrict the imagination and participation of the viewer. Enchantment does the opposite: at its best, it allows the participant to be a full partner with the artist in making the artwork – maybe that is a lesson in democracy Tolkien can show us. The apex of enchantment is the creation of a believable secondary world through art; when done with care and attention to beauty it can stir millions to enter and maybe allow us to see our own world a little clearer – perhaps that is what JRR Tolkien was able to achieve.

Works Cited

Arvidson, Stefan. ‘Greed and the Nature of Evil: Tolkien versus Wagner’ Journal of Religion and Popular Culture, Volume 22(20: summer 2010).

Carpenter, Humphrey (2000). J.R.R. Tolkien: A Biography. New York: Houghton Mifflin.

Dickerson, Mathew (2003) Following Gandalf: Epic Battles and Moral Victory in The Lord of the Rings. Brazos Press.

Flieger, Verlyn (2002). Splintered Light: Logos and Language in Tolkien’s World. Rev. ed. Kent, OH: Kent State UP.

Franklin, David and Sebastian Schutze (2011) Caravaggio & His Followers in Rome. Yale University Press.

Hammond, Wayne G. and Christina Scull (2004). J.R.R. Tolkien: Artist & Illustrator. London: HarperCollins.

Jackson, Peter, dir. The Lord of the Rings. Screenplay by Peter Jackson, Fran Walsh, and Philippa Boyens. Perf. Elijah Wood et al. New Line Cinema, 2001-2003. Special Extended DVD Editions. United States: New Line Home Entertainment, 2002 – 2004.

MacLeod, Jeffrey J. and Anna Smol. “A Single Leaf: Tolkien’s Visual Art and Fantasy.” Mythlore 27.1/2 (#103) (2008): 105-26. Print. Available for download: http://ec.msvu.ca:8080/xmlui/handle/10587/566

MacLeod, Jeffrey & Anna Smol. “Tolkien’s Painterly Style: Landscapes in The Lord of the Rings” Conference paper for the Mythopoeic Society, Michigan State University, East Lansing (July 12, 2013 ).

Mathijs, Ernest, ed. (2006). The Lord of the Rings: Popular Culture in Global Context. London and New York: Wallflower Press.

Miller, Miriam Y. “The Green Sun: A Study of Color in J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the

Rings” Mythlore 1.7 [4.26] (1981): 3-11.

Rosebury, Brian (2003). Tolkien: A Cultural Phenomenon. 2nd ed. Basingstoke and New York: Palgrave MacMillan.

Shippey, Tom (2000). JRR Tolkien: Author of the Century. Harper Collins.

Tolkien, JRR. “Leaf by Niggle” (2003). Tree and Leaf, including the poem Mythopoeia. London: HarperCollins, pp. 93-118.

Tolkien, JRR. (1995). The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien. Eds. Humphrey Carpenter with Christopher Tolkien. London: HarperCollins

Tolkien, JRR (2004). The Lord of the Rings. 50th Anniversary Edition. London: HarperCollins.

Tolkien, JRR (2001) “On Fairy-Stories.” Tree and Leaf, including the poem Mythopoeia. London: HarperCollins, pp. 3-81.

Tolkien, JRR (1999) The Silmarillion. Ed. Christopher Tolkien. London: Allen & Unwin, 1977. London: HarperCollins.

Tolkien, Priscilla. “My Father the Artist.” Amon Hen: Bulletin of the Tolkien Society 23 (1976): pp. 6-7.

[1] See Tolkien’s essay “On Fairy Stories” for a complete description of the concept of Elvish Craft. In brief, it refers to the process an artist uses to create a believable imaginary/secondary world.

Featured image by John Howe.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Tolkien is amazing. If anyone gets the chance, I highly recommend reading his lesser known book, “Roverandom”.

It’s a beautiful story that he created for his son, Christopher, when he lost his toy dog on a beach. It’s a really great story.

Roverandom is a great read. I also recommend ‘Leaf by Niggle’ – this story deals directly with the struggle with art-making and ‘life after death’.

Had an old damaged copy of The Hobbit years ago and I cut some of the pics out and framed them: http://i.imgur.com/DzD0f1j.jpg

You are a true fan! I’m told there is a new book coming out which if full catalogue on his artwork, I hope that is true.

Thank you Jeff, great article.

You’re welcome.

Great art or no, Tolkien’s illustrations are at least better than his bloody songs.

You got me there – I’ll leave the song article to someone else. Thanks for the comment.

I’ve always thought that Tolkien’s landscapes are beautiful and evocative, though his people are dreadful. The cover of the first edition of The Hobbit, in particular, is wonderful. How he found the time to do them, I can’t think.

I agree with you. It would have been interesting to see how far Tolkien would have taken his art if he had the time.

I’m surprised he didn’t illustrate more of his own books. Paulkine Baynes illustrated a lot of his books

Tolkien was very critical of his own art. An early critic of The Hobbit praised the text but derided the art-work Tolkien included, I think that damaged his confidence. He loved Barnes’ art, I think he met her through a recommendation by CS Lewis.

I’m a huge fan of Tolkien’s imagined world, with its broad narrative sweep, imagined history, and accompanying cartography.

You and I agree. Tolkien developed his cartography skills during WWI as it was part of his duties as a British officer.

Middle-earth is real.

I agree!

Thank you, all. Tolkien’s visual art is “enchanting.”

And I agree with Blake, Middle-earth is real.

Jeff, in regards to Smaug-I appreciate your choice of colors, positions and execution.

Thanks, Venus. Your kind comment inspires me to attempt to make more art.

Thanks, Venus. That painting is fairly large, about 2′ x 3′. I enjoyed painting it and I may try again to render a dragon – a challenging task!

I think Middle Earth is certainly as real as Hogwarts or the Hunger Games, and I have read Tolkien’s marvellous trilogy a dozen times, I think. Not sure that best-selling equates necessarily to best quality in the 20th Century though!?

I agree, sales is only one indicator of ‘success’. I’m more impressed by the impact art has through the affect it has on the viewer/reader; that a difficult thing to measure, but you know it when you see it.

Awesome read! Really well researched. Tolkein is a damn genius!

Thanks! I agree, Tolkien was a genius in the true sense of the word.

Tolkien was proficient in calligraphy. You can see his art that utilized these skills are by far the most interesting and mature of his works.

His mother practiced calligraphy, I think he picked it up from her, although she died when he was still a child.

I have always liked his work and wish more of the Tolkien related stuff would look to it for inspiration.

I agree.

J.R.Art. Tolkien

Clever. 🙂

He has a really interesting style of writing.

Yes, it is deceptive, he gives you enough for you to add the details, at least that it was I assert.

Yes, poetic in that sense.

One of the oddest Tolkien artists, but one who Tolkien did admire was Cor Blok, who really went to town with the impressionistic view of Middle Earth. His pictures are quite crazy, but entirely fitting for the fantasy landscape. Here is a link if interested: http://fan.theonering.net/~rolozo/cgi-bin/rolozo.cgi/collection/blok

Yes, Blok is unique – I don’t care much for it, but Tolkien liked his work.

As much as I like LOTR (and to a lesser extent The Hobbit) I didn’t think that most of the illustrations were particularly good – a bit lumpen,in my view.

This is a very valid point, his art is not to everyone’s taste; my own style is quite different from his.

Tolkíen was a good visualizer.

I agree, I describe him as a visual writer.

Lovely selection of artwork you’ve presented with your essay.

Thank you very much, Katelyn.

Thank you for the read!

You’re welcome. Thanks for taking the time to read it.

He’s dead and gone. Some of us artists are alive and ignored.

Tolkien died, but his art is very much alive. I see your point though, as an artist myself I understand the struggle to get noticed.

The films of The Lord of the Rings come nowhere near to reproducing Tolkien’s imaginary world, visually or otherwise.

I think the films made some interesting insights into Middle-earth, but overall I agree with you.

I was fascinated by the beauty of his maps and runes when I was a child reading The Hobbit and the Lord of the Rings.

Tolkien created a unique runic alphabet, and invented two more-or-less complete languages (and elements of other languages) to support Middle-earth. He also completely designed the original map of Middle-earth (with some help from his son) which appears in many versions of the editions of the published books.

Tolkien created a world, not just a story.

I agree, he did create a world – which you help complete every time you read his work or engage with his art.

Yes, Tolkien took me to a whole new world I could explore through reading and then in my imagination.

I think he helped shape a lot of us through our imagination.

I just want to say that the art work is awesome, and it has really great detail. Your article is also awesome as well.

Thanks, Aaron. I connect with Tolkien on an artistic level, that’s why I admire his writing and painting so much.

Tolkie’s stories are so deep scarred in so many peoples lifes.

Yeah, these stories are filled with enchantment.

I have always loved Tolkiens story’s and his art gives an insight into his world.

I agree, Blackwood.

Amazing to think that Tolkien found it just as necessary to escape into fantasy as the millions of caged humans who grasp at books, DVDs, music, TV and films as an alternative to what’s going on outside their front door.

Yes, the escape of the prisoner. I’d never want to live in a world without art and stories.

I’m not sure that “escape into fantasy” is the right way to put it. In one sense he was trying to wake people up to what was going on outside their front door, not hide it away.

Poor comment.

LOTR is awesome. Much like my imagination of the story before any of the films.

That’s good point. I wonder what it would have been like to see the films first and then read the book? I imagine the visuals of the movies would have a strong impact on the reception of the story as a text.

I watched the films first – i was 11 at the time! – and the books seemed more ethereal to me than the films. Kind of more childlike?

I see your point,Francesca. The books are more of an open canvas, the films, by the nature of the medium, impose a bit more on your imagination through the strong visual imagery they present. Can anyone else ever play Gandalf after Sir Ian?

What a good read. Though I have to confess I never cared for his artwork. To me, the true mastery of Tolkien’s work lay in the way that the world he invented seemed to already exist somewhere in my memory.

Well put. Tolkien’s art gives insight to how his mind works, but I accept that it may not be a strong as his writing craft (although I like his visual art). Tolkien once stated the felt the Lord of the Rings was a story which already happened and he was just transcribing it.

His style was entrancing to me at a young age …. really magical – clever and singularly evocative.

It had the same impact on me, I first read The Hobbit when I was 11, I read the Lord of the Rings two or three years later.

A cherished possession of mine is the first Tolkien calendar, featuring his illustrations. They have informed my every reading of the books, and there have been, literally, too many to count.

Many talented artists have attempted to render Middle-earth, my personal favourites are Allan Lee and John Howe (both of whom were conceptual artists for the Jackson films).

I really love the quotes you chose for Tolkein’s descriptions. I haven’t read LOTR in years, and it is nice to see the descriptions in isolation as it does remind me that his writing is beautiful as well as scholarly. Almost like creative-non-fiction fiction! My favourite is Smith of Wootton Major – lovely Faery story that always feels like it could have happened in my town…

You’ve said it! His writing allows us to help make his world seem like one we could live in. That is powerful art, a true faerie story.

There is nothing quite like Tolkien’s own illustrations…

I agree, he has got his own style.

Great insight, great pictures.

Thank you.

The Lord of the Rings is without question one of the great books of the 20th century.

I’m a political science professor by training, so I joke with my English prof friends that is not my opinion, it is a fact that Tolkien is the greatest English-speaking writer of the 20th century – I usually get a raised eyebrow in return, but my friends put up with me.

He was a pleasant enough artist, but no sort of genius. His books are among the finest ever written for children – but that’s what they are – for children. Adults reading them should grow up.

I resist entirely the need to grow up.

But if we all grow, how will any of us ever write things for children so those children can grow up well?

That is a good point. Also, the Lord of the Rings is not a children’s book. Tolkien takes on the argument about fantasy being a child’s genre in his essay’ On Fairy Stories’; I think he skewers the argument that only children can appreciate and ‘like’ fantasy literature.

I know plenty of adults who couldn’t decipher his prose.

That’s true. Tolkien said he work should appeal to “clever” children and sophisticated adult readers.

He should have done much more painting and much less writing.

I’m glad he did both.

Tolkien’s art is received like his writing.

I agree.

Tolkein was a talented artist.

I agree, he had skill at a variety of levels.

The section on magic/enchantment was truly brilliant. I think that it is one of the most underrated parts of fantasy and not much attention has be directed towards how authors use it. Great article and very thought provoking

Thank you! I was inspired to reflect on magic and enchantment after I first read Tolkien’s description of elivish craft in his easy ‘On Fairy Stories’. That essay is really the behind-the-scenes notes on how he approached the making of Lord of the Rings as an artwork.

I’ll admit freely: I skimmed parts of this article. It’s very long, and I was having a hard enough time marshalling my thoughts on the parts I did read. Your analysis is interesting, and shows a good grasp of the creative process, but I feel like you’re not giving enough weight to certain aspects. In particular, prejudice. You talk about Lord of the Rings, etc. as being an objection to absolute power, and I certainly agree with that, but I think that as a whole creation it’s too charged with Tolkien’s own biases and understandings to be apolitical even a little bit. He does offer insight into values rather than institutions, but that insight is coloured by his own world view, and that needs to be taken into account when considering the politics of his writing. He had a lot of very interesting ideas, and he created an incredible thing, but in a lot of ways it’s not a diverse creation, and because of how influential it was mainstream fantasy has become a much more narrow genre- or perhaps it was narrow before, and Tolkien only encouraged it. It’s hard to say where the beginnings and endings of genre mutation are, because it’s so organic, and everything affects everything else.

Tolkien created an amazing thing, and he said many things therein that are very positive. All of his overt messages and the general impression of his art and his writing is a progressive, evolutionary one that has for good reason captures thousands of minds. But every writer is trapped by their own world view, and Tolkien’s does seep through. This is a good article and a good exploration of some aspects of his creativity and the sum of his work, but it might have been deeper and better still if you’d looked a little more at the more subliminal and subconscious politics of the writing.

Thank you for your interesting comments.

I do agree with you that an artist is bound to include their own bias/world view in their work, I just don’t think Tolkien was “trapped” by it; indeed, he embraced his lens on the world and built an artwork that is still growing in influence over 50 years after its publication. If his was trapped then a lot of us are trapped with him.

I’m not sure what you mean by a “diverse” creation, but the fantasy genre has not been made narrow by Tolkien, if anything, it has expanded. Many have tried to clone Tolkien’s work and none have matched it, but in other aspects of fantasy literature authors and artists have gone in entirely different directions and have created impressive work. Even a brief glance at the list of The Artifice articles on this subject shows the incredible volume of material produced.

On your last point, I do agree there is much more which can be explored on the subject of Tolkien’s art and politics. And I like the idea of “reading” texts on their sbconscious level as I think there is where “art works.” I’ve explored this subject in an article I’ve published elsewhere called “Imagery as Political Action.”

Again, thank you for your comments, I enjoyed reading and discussing them here.

Never got around to reading anything of Tolkien’s stuff. But the article is very thought out, and well executed. Kudos !

Thank you.

REALLY like the original Hobbit cover.

Me too, I think it inspired a lot of artists later.

Interesting stuff. Many of Tolkein’s literary themes and locations were influenced by his early life – Mosely Bog and Sarehole Mill just outside Birmingham, England are often cited as influences on his vision of the Shire and the Old Forest.

I wonder how these childhood locations might have contributed to the “spiritual and meditative quality” of his artwork.

Thanks, Simon. I think his time spent in rural England (especially Sarehole) as a a child, and the fact he was raised by a Priest after his parents died contributed to his affection for forests and farms, as well as his spiritual and Catholic beliefs ( add to that his deep study of pagan and other pre-Christian traditions, too).

Really brilliant article. I just love how in depth Tolkien went with his work and how his work (and fantasy) reflects reality. One day, when George r.R. Martin has finally finished the ASOIAF he too will do a Silmarillion-esque book for Westeros and Essos.

Thank you for this kind comment.

Is anyone going to left alive after Martin’s last book from the ASOIAF? 🙂

HBO will certainly be crossing they’re fingers

You bet 🙂

Brilliant article, so thorough and well-written. All your arguments stand, and I love how you’ve taken different positions – written style, visual style and politics. The comparison to Impressionism is especially fascinating. Well done!

Thank you, Rachel. I very much appreciate your kind comments, espcially those related to how visual art and Tolkien’s work is linked.

Jeff I enjoyed this post immensely, you seem to have done a thorough bit of research and it has paid off. Your ideas flow nicely and the analysis weaved well with the commentary.

Thank you, Bethany. I am a fan of Tolkien but also do scholarly work on Tolkien studies as well. I’ve published work in the journals Mythlore and Mallorn. But I must say I enjoy the feedback from publishing in The Artifice the most.

Great article! Though everyone always talks about Tolkien’s written work, I’ve never before read any approach about his drawing and paintings. I’m a big fan of his visual work (I even have his Smaug drawing tattoed on my back) and I think it’s totally underrated.

Wow! Your passion for Tolkien’s art cannot be questioned with a tattoo of Smaug – I’m impressed. I hope to see more attention on Tolkien;s visual art as it is often overshadowed by his prose work.

There is a tremendous amount of information in this article, and a pretty good “works cited” list as well. The author moves in and out of the discussion, advancing the thesis while playing off of other experts. My main problem with the article is not the content so much as the framing device–the notion/thesis that Middle Earth is “real.” It’s not a very effective hook, and whether one believes in “real” or not, the information in the body of the article is still interesting, except when it’s a little off the mark. For example, the politics of Middle Earth are quite recognizable–it is a world that believes in the “divine right of kings,” and celebrates the traditions–Medieval as they are–as something much better than English democracy. Who wouldn’t want to serve under the god-like king, Aragorn? There is a clear racial and gender hierarchy in LOTR as well that would be very familiar to conservative readers. Further, the work plays out as a Crusade Tale: the White versus the swarthy dark-skinned evil southerners/Orcs who inhabit the land of Mordo–i.e., Mordor. Far from unrecognizable, LOTR is very recognizable as symbol and metaphor for Tolkien’s longing for an age where the world worked much more simply than it does today. But the question remains: is there a mythological past that somewhere lost in the mists of time where evil is evil and good is good?

Thank you for this thoughtful response.

I’m not sure I agree that the politics of Middle-earth is as clear as you assert, although with some of your points. However, Aragorn had to earn his title and was reluctant to take it when offered; also, the fellowship of the ring was about as democratic as you can get, hardly ruled by the barked orders of an entitled king. Tolkien had a subtle mind and so I think his work is very sophisticated in its treatment of political ideology.

On the premise of the ‘realness’ of Middle-earth I merely want to point out that powerful works of imagination have a great impact in the primary world and are not simply ‘escapist’ as they are so often described. Also, neuroscience shows us that practicing and experiencing art can actually change your brain, it doesn’t get more real than that.

Again, thank you for your comments, I appreciate your feedback.

I never knew about Tolkien’s art, and I’ve always considered myself as an expert in anything Middle Earth. A wonderful argument, and a beautiful presentation. Overall, a fantastic article!

Thank you! I’m glad I opened the curtain a little bit more on Tolkien’s art for you.

Love this article: so glad to read one about Tolkien which doesn’t JUST focus on WWII.

Thanks! I agree with you, Tolkien was much more than a soldier in the Great War.

I have to agree there, especially the part about spirituality, which I didn’t think about before. Also, not to nitpick, but I think that you’re probably referring to WWI, where he served in the army and fought on the Western Front in France. In WWII, he was a codebreaker. I think Jeff read between the lines and assumed, but just wanted to point it out.

This article is amazing. I’m currently doing research for a paper about Tolkien, and your writing has opened my eyes to how in depth and intricate his writing is.

Thank you!

You’re welcome. Good luck with your paper.