The Debatable Importance of Historical Accuracy in Period Films

In retrospect it seems vaguely humorous that the future American President Ronald Reagan should have found himself cast as the celebrity-seeking martinet George Armstrong Custer in the 1940 Warner Bros. Western Santa Fe Trail (1940). The picture purports to recreate a famous chapter in American history, following its heroes — all recent graduates of West Point and future leaders of both the Union and Confederate armies — as they head out along the Santa Fe Trail and soon thereafter take a detour off the important caravan route from Missouri to New Mexico. The film Santa Fe Trail concentrates instead on the conflict between the Army and the abolitionist John Brown. In reality, only Errol Flynn’s character, J.E.B. Stuart, graduated from West Point in 1854, the year in which the film’s action is set. Sitting squarely in the middle the fence, refusing to side with either the South or the North, screenwriter Robert Buckner tries admirably to simplify matters as illustrated by the following dialogue delivered by J.E.B Stuart (Flynn) when he is asked about the dilemma between slavery and insurrection: “Our job is to be [soldiers], not to decide what is wrong or right.” Politically muddled and historically confused it may be, but the film rarely falters as entertainment.

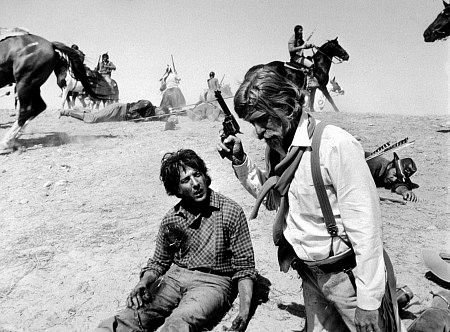

General Custer, an oft-vilified and rather ambiguous figure in American history, was also brought to life on the big screen by comic actor Richard Mulligan in Arthur Penn’s Western epic Little Big Man (1970). Infused with the same serio-comic sensibility Penn brought to his revolutionary 1967 film Bonnie and Clyde, Little Big Man is in essence a more politically aware precursor to the relatively harmless populism of Forrest Gump (1994).

The film opens in the present day with Jack Crabb (Dustin Hoffman) — at this point a cantankerous 121-year-old who claims to be the only white man who survived the Battle of Little Big Horn — being interviewed by an incredulous young historian (William Hickey). Jack tells his misinformed interviewer to just sit back, shut up and listen — he has a few things to say about Gen. Custer, and an assortment of historic events from the latter half of the previous century. He was there. He experienced them.

What follows is a sprawling, not-too-serious investigation of terribly serious subjects such as manifest destiny, the government-sanctioned genocide of Native Americans, religious and sexual hypocrisy, and the folly of war. Jack’s sometimes absurd embellishments of each story are a particular highlight, because you’re never sure, in fact, if they are falsehoods or the truth. If history proves anything, this film tells us, it’s that crazier things have happened. Over the course of the film, Jack spends time variously as a Western settler who’s kidnapped and raised by peaceful Cheyenne Indians, as an orphan being pursued by a lecherous preacher’s wife (Faye Dunaway), as a snake-eyed gunfighter, as the sidekick of a medicine show con artist (Martin Balsam), as a down-and-out drunk, and as a scout for the vain, egotistical and utterly buffoonish General Custer (Mulligan). Sarcastic though its tone may be, I have a hunch that this picture’s portrayal of Custer is probably closer to fact than Ronald Reagan’s glorified iteration of the man in Santa Fe Trail. It is the rare film that manages to be both a reasonable facsimile of history and an immense entertainment simultaneously. Little Big Man does this. Santa Fe Trail does not.

Little Big Man fits nicely into the subgenre known as the Revisionist Western. Popularized primarily in the late ’60s and early ’70s, such films as Sam Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch and George Roy Hill’s Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid came to define this style of moviemaking, as audiences and directors alike began to question the idealistic way in which the old American West had been previously portrayed on film.

It may be that Robert Altman’s McCabe and Mrs. Miller (1971) is the definitive Revisionist Western. Altman once called the film an “anti-Western,” owing to its subversive elements. The film focuses on the romance between a gambler named McCabe (Warren Beatty) who arrives in a town called Presbyterian Church — so named due to the central location of the house of worship. McCabe soon establishes a brothel, and quickly develops a romance with his business partner, Mrs. Miller (Julie Christie at her best). Such risqué subject matter would have been prohibited under the strict rules of the recently abolished Production Code, and Altman took advantage of a momentary lapse in censorship to show audiences what he imagined the American West would actually have been like. He opted to shoot the film in the winter months in British Columbia, rather than in John Ford’s Monument Valley home base, which was largely responsible for mythicizing the West in the minds of the general public. This locale provided Altman with a heightened sense of realism and makes McCabe and Mrs. Miller one of the more authentic pieces of cinema to be produced by its genre. Indeed, this is quite probably as close as movie watching will ever get to time travel.

How interesting that Altman’s breakthrough film, the previous year’s MASH, should have turned out to be one of the most historically questionable films to come out of Hollywood. Ostensibly it is the story of a team of American doctors working at a frontline Army Hospital during the Korean War. But Altman’s genius is that he frames this story within a socio-political context which would be more relatable to disillusioned American audiences of the early ’70s. With their long hair and rebellious attitudes, the characters played in this film by Donald Sutherland and Elliott Gould have more in common with the protagonists of Easy Rider than with the more traditional heroes of previous war films. MASH is really part of a subgenre of period films which are best understood as being intentionally anachronistic.

The best example of this kind of picture might be writer-director Sofia Coppola’s 2006 film of Marie Antoinette. It has been well-established that the doomed wife of Louis XVI of France was never actually quoted as saying “Let them eat cake,” yet Kirsten Dunst in the title role utters the infamous phrase almost, it seems, to deliberately vex the audience. As this film’s soundtrack proves, the music of the movies can be just as important as the dialogue and visuals in terms of capturing a specific moment in time. I am reasonably sure that audiences would have reacted to Coppola’s film differently had it been lacking a score comprised primarily of music from New Wave and post-punk bands such as Siouxsie and the Banshees (“Hong Kong Garden”) and New Order (“Ceremony”). Coppola employs this music for a specific purpose, it is worth noting. Juxtaposing the decadence of eighteenth century Versailles with the Bow Wow Wow song “I Want Candy” lends this film a greater relevancy to modern audiences and places the story in a context that the average viewer can better grasp.

Coppola’s Marie Antoinette was an Oscar winner for its costume design and you would be hard-pressed to find a film which better captures the look of the period in which it is set — or at least our presumption of how a period should look. Admittedly, it is plainly clear that Stanley Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon (1975) was a profound influence on this film’s visual sensibilities. However, I would argue that Coppola’s unprecedented access to the Palace of Versailles increases this film’s visual authenticity inestimably above the Kubrick picture.

Certainly, at least, the importance of historical accuracy in period films is debatable. The historian A.E. Larson has pointed out the profound effect of Mel Gibson’s Braveheart on Scottish politics of the mid-1990s. The film’s negative portrayal of the English was largely inaccurate, but it nonetheless helped pave the way for the 1997 referendum which resulted in the foundation of the Scottish parliament. Likewise, Oliver Stone’s JFK persuaded an alarming number of Americans that Lee Harvey Oswald was not acting alone when he assassinated John F. Kennedy. In short, Larson argues, do not underestimate the power of films to alter a society’s beliefs.

In that sense one could make the case that it is somewhat troubling that the Scottish people were influenced, in part at least, by a fictitious Hollywood movie to fundamentally change their system of government. Having said that, I remain unconvinced that any intelligent and discerning moviegoer would blindly accept period films as fact rather than fiction. Since historical events are rarely as entertaining as the movies they inspire, it is crucial that filmmakers be granted a great deal of leeway when it comes to accuracy.

Indeed, as Oscar-nominated costume designer and historian Deborah Nadoolman Landis has stated, “Period costume design must always resemble the year in which the film was made. The audience wants to recognize, and relate to, the characters in every story.” In other words, if the appearance of the film is in any way distracting, filmmakers risk losing the attention of their audience. When Hollywood and international films turn their attention to historical events, modern relevancy is — for good or ill — more important than accuracy.

Works Cited

Nadoolman Landis, Deborah. Hollywood Costume. Harry N. Abrams. ISBN 9781419709821.

Phillips, James. Cinematic Thinking: Philosophical Approaches to the New Cinema. Stanford University Press. Page 55. ISBN 9780804758000.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Films such as Operation Daybreak, Gladiator, Is Paris Burning and The Lives of Others all contain inaccuracies but they do at least try to remain true to real events and/or give an accurate impression of what it was actually like. These films will also often encourage people to find out more.

Films like Braveheart and Pearl harbour are just an insult to peoples intelligence. The trouble here is that many people will see them and think this is what happened.

Film producers often argue they are making a film not a documentary, but you don’t need to sacrifice authenticity for drama. Valkyrie and the Battle for Algiers were both exciting and very accurate.

The key is striking the right balance. While the story in Titanic was pure fiction (aside from the ship sinking) the set and costumes appear well researched. In Atonement they appear not to have even bothered with the basics e.g: a Lancaster bomber flying 4 years before it was even invented??

A film being historically inaccurate is only a problem if it pretends, non-satirically, to be historically accurate.

Great article! Historical inaccuracy in film is not bad, but it does depend on what you are changing. Overdramatizing battles or feuds between two people is one thing, but completely changing a persons backstory just for the plot is simply lazy.

Films are only one facet of the prism through which history is presented to us. They’re not the primary medium. That’s sources, interpretation, historical writing. There’s always something lurid about films, even the best of them. Compare original source film / photography of Nazi atrocity with Spielberg’s ‘Schindler’s List’, authenticism- seeking dramatisation if ever there was.The fact of the comparison in the first place gives ‘Hollywood distance’, and even burning truthful scenes are rendered for the camera, in a way that what they attempt to replicate wasn’t, if it was ever seen at all beyond victims and perpetrators.

Put films in context. They are not that important. Although they may be influential. That’s a different issue.

Hollywood and sticking to the facts? What Hollywood movie ever came close?

Braveheart is a shockingly bad film, both for its mashing up of history and the ever so cheesy last line of William Wallace; “FREEEEEEEEEEDOM”. How a film with Mel Gibson flaunting about in a kilt was nominated for ten Oscars, and ended up winning five, is beyond me.

Well I’m Scottish and it probably just shows that not many people know about or care about Scottish history. Understandable to some extent as there are 100s of other countries (and some a lot bigger!!) in the world. I mean some people think Highlander is accurate 😉 – and it wasn’t even filmed in Scotland.

Braveheart is just astonishing. It contains about as much historical truth as The Lord of the Rings.

Oscar-winners, especially in the past 20 years or so, are as much victims of their era as anything else– I mean, Crash?

The thing about the current trend for true story films is that, first and foremost, they represent a terrible collective Hollywood failure of imagination. Even when the events they depict are entertaining or interesting, they just play themselves out with leaden linearity. They’re not satisfying as stories. The fact that they’re also often not even faithful to the truth just shows that lying and fictionalising aren’t the same thing.

If you want history don’t go to a cinema… go to school, a library or open a book.

This might not apply to everyone, but a lot of my personal enjoyment of a film comes down to its credibility.

Now, if a film is quite confidently set in a world of suspended disbelief, then I don’t mind. I’ll take a Tarantino, a Wes Anderson, a Matrix, Lord of the Rings etc. any day.

But if the point of a film is to tell a story using the real world (past or present) as its setting, then I like it to be believable – you could say ‘accurate’.

I get a far more cathartic experience from a film if it feels real. Did I think Argo was an OK film 2/3 of the way through, in spite of Ben Affleck’s visage resembling a mopey mask throughout? Yes. But the cheesy make-believe ending totally ruined it. I can’t believe it won an Oscar.

So as far as I’m concerned, whether historical films are taken as fact or not is irrelevant: I’m far more likely to enjoy them if they’re accurate – your emotions are responding the reality of the story rather than the manipulations of the director.

The problem is not historically inaccurate films, it’s that people accept filmic representations of history as fact.

Exactly, I couldn’t agree more with this comment here. Because of how gigantic Hollywood and films are in mainstream society, it makes it all the more crucial for the facts to be a faithful to the truth as possible. Unfortunately though, given that film-makers and producers are ultimately more interested in making money for the sake of entertainment, some cultures’ entire traditions, heroes, and stories (even historical events) too often get tossed to the wayside and may become even more misunderstood by those who fall under that so-called “lowest common denominator.” What was done to William Murdoch in Cameron’s Titanic, demonizing him for the sake of drama (while ignoring that he had survived the sinking instead of committing suicide) was probably one of the most blatantly unethical ways of doing so ever in a film that billed itself as being “historically correct” with its portrayal.

A lot of good points here (and in the comments thus far). Have to say that one of my pet peeves is when an author is so intent upon showing how much research they’ve done than in telling the story. This is a bigger problem with text than with film, but I’ve seen many elements in both kinds of work that were shoe-horned into the story to show off authorial knowledge. It always bugs me.

I feel like this articles is the beginnings of an idea for an article about whether historical accuracy is important or not. Pursue this topic more and come back to it. You have so much more you could do with this!

God can’t alter history, film directors can!

Films are works of fiction. And I say this as an academic who teaches film studies. Yeah, it’s fun to figure out what’s fact and what isn’t (if that’s even possible much of the time…), but fiction films are not historical documents. Even documentaries are not historical documents.

I loved Monty Python’s response to Passion of the Christ: ‘Same as our film, but without the jokes.’

“The human face is the great subject of the cinema. Everything is there.”

– Ingmar Bergman.

Interesting topic. As a history student, I always get bugged about weird (often misplaced) modern things within a historical film. The Deborah Nadoolman Landis quote in the conclusion wraps up the article well. I am not sure I agree that accuracy is less important than relevance, but a well written article with good points and examples. Perhaps it would be interesting to further examine less popular, more indie films, such as “girl with a pearl earring”. It is a social commentary to see that actual brutally historically accurate films, are very unpopular.

“Intentionally anachronistic” frames of mind can lead to the most convincing stories. When I am at home, perusing Netflix, I am looking for entertainment, plot and character development bar education. John’s notion that historical accuracy does not always make for the best story is, well, true. There is, of course, value in cultural and historical accuracy. It just is not always necessary.

I particularly like: “I remain unconvinced that any intelligent and discerning moviegoer would blindly accept period films as fact rather than fiction.” Congrats guys! We don’t all blindly believe everything told to us.

Further, “historical fact” is, in itself, only factual because a historian once named it thus. Film is just another theoretical (though lucratively designed) interpretation of history. Perhaps some of the oldest stories we know, particularly those with religious basis, were deemed “historically inaccurate” in their time.

What is wrong is when film (or TV, or books) present themselves as something that they are not.

Stone’s “JFK” is a prime example – it almost needs a health warning edited into the beginning of the film.

is there any actual proof that anything happened in history, or is it just opinion?

The problem I often find is that most people are too lazy or indifferent to do their own research. They are happy to accept whatever Hollywood dishes up to them as fact. I know plenty of people who watch films without questioning what they see.

This is an interesting topic and one bound to have a boatload of opinions. My personal stance on the topic stems from what has been called the number one rule in film-making: Don’t be boring. When 100% fact is boring, then it’s time to spice up the plot-line or give the characters a nuance they perhaps never had. Sometimes that may turn what is supposed to be a biopic into a work of historical fiction (a la Yankee Doodle Dandy and The Untouchables), and that’s perfectly okay.

Historical movies and Biopics are still FICTION.

I think the qualifying term here is “based on.”

None of the films purport to be documentaries or historically acurate. They are filmmakers interpretations of a story.

Besides, it’s showbiz innit?

The other standard qualifying term is “inspired by”, which means it’s even more historically bogus than “based on”.

I think Sari has it correct. Propagandists rely on that affect. I get a kick out of the tag line, “Based on a true story”. They never really tell you how much.

That said, any intelligent viewer is going to understand that films are entertainment. They are aware of “creative license” being employed. Realize also that any major film is subjected to unbelievable scrutiny by the producers whose primary purpose is to sell the story. That means a return on investment, so the standard ploy of any salesman of bending the truth a little to make the sale is, in their mind, an obvious and accepted practice.

I also question whether it’s truly possible to be completely “historically accurate”. Any historian necessarily infects his subject with his interpretation of events. To arrive at any semblance of the truth of an event you have to look at more than one account.

The real sadness in this debate is what has happened to what used to be called “journalism”.

I was about to make a comment on Inglorious Bastard but then found “Quentin Tarantino Says “Inglorious Bastards Not a Period Piece””, which should have been obvious now thinking about it.

They are movies and their job is to get people interested in a subject they do not necessarily understand or comprehend. Watch the movie then do your own research on the subject, if it is of interest to you. Movies are not factual historical documents, they are entertainment which can, if done well, pique interest.

In most cases, if you are looking for historical accuracy, don’t watch commercially produced films.

This is such a great topic– people tend to be so focused on whether or not an adaption of a novel to the screen is true to the source or not, that no one ever questions whether we are dumbing ourselves down by assuming the historical genre is actually remotely historical.

Modern relevancy is only relevant when picking which historical event to interpret. In the making of the film, however, historical accuracy–at least to me– maintains supremacy. Easier said than done no doubt. Instead of taking a historical event and changing it’s literal qualities to make a movie, let’s use technology and modern advances to accurately depict the past and study it.

What I haven’t noticed here in the comments yet is a discussion of revisionist histories that are damaging to a minority community (or maybe I just missed it! Sorry if I did)… I personally am okay with sacrificing some historical inaccuracies in most of the period films and TV that I consume–I think of Downton Abbey and its wonderful trainwreck of anachronisms. But it becomes majorly problematic when those revisions of history are erasing the stories of marginalized peoples. A recent example is the upcoming film Stonewall, which takes a story about a riot started by mostly trans* people of color and replaces the heroine with a young white gay male. Lady Mary incorrectly blurting out, “I’m just sayin’,” now seems trivial in comparison to the entire erasure of a minority community’s history.

If the film deals with prominent historical figures, then the importance of maintaining at least some historical accuracy is not that debatable… I mean, of course it’s movies and their details shouldn’t be too obsessed over, but nobody wants another Reign situation: https://prettyandwittyandbright.wordpress.com/2014/10/03/on-tv-revisting-reigns-first-season-and-the-horrors-of-historical-fanfiction-ahem/

John,

I would be split with my opinion and probably bore the reader with my elaboration, but I would suggest that we make sure that if the statement “based on a true story” that the creative liberties are strict than “inspired by a true story”. Personally I enjoyed watching “Band of Brothers” which was even said in the making-off that they combined various historically accurate events into one location or one character. While not true per-se it has been condensed with facts to make it more entertaining for the short period the filmmaker has.

On the other hand, if we have a movie called “Lincoln” my assumption and expectation would be, that this is a movie that would portray the titles character as close to the “real deal” as possible, while eventually condensing surrounding characters and events as in BoB for artistic reasons. If you want to make it less accurate, call it “Lincoln the Vampire Slayer” and I don’t think anyone will expect any accuracy here.

Finally, as I have been reading a lot of essays on rhetorical history lately, I agree with some of the previous comments that we can not always be sure what “true history” actually is. After all, the winners write history, and there will always be people who are going to scream “bias” when someone criticises their favorite historical character or period of time. But we shouldn’t “expect” people to know what is and what is not accurate. Just as we implemented a rating system so that people would know that Mad Max is not child friendly, we should consider a “historical accuracy” meter, even if that would mean the end of the History Channel!

Great points about McCabe and Mrs Miller. It might also have been interesting to go deeper into how the film’s micro elements combine to create authenticity.

When I walk into a movie, unless it is a documentary (although even then) I expect to be told a fascinating story that will hold my attention. That being said, if I have studied the subject matter and find too many inconsistencies with the film in front of me and my own research it makes it difficult for me to suspend my disbelief and enjoy the story.

I always try to remember that when you see a movie you are seeing it literally through someone else’s lens, that person being the director, screenwriter, producers, editors and of course, the actors. Which, really, when you think about it, history is also always seen through someone else’s lens as well. So when a movie maker decides to make his/her own history so to speak…they are doing the same thing historians have been doing forever; which is picking and choosing which elements of a story to bring to the forefront and which to leave in the background.

That being said, any story that aggrandizes someone who isn’t worth it, is not a movie I like to watch and I avoid historical films that give too much credit to white male history without including all the other people who were there too.

As a writer I often struggle with historical relevancy. In one of my plots I have the two main characters getting married only months after meeting, and then the rest of the time they are married and have to go through the relationship struggles while dealing with the main plot. It’s something I took a long time thinking over because in today’s culture it is much more appealing to have the characters marry at the end of the story. This modern trend allows for sexual tension and anxiety over whether the characters will end up together at the end. The debate is then to follow historical accuracy and provide reader appeal in other ways or to follow the modern trend and use proved methods of keeping an audience’s attention.

I don’t have much to add to the discussion as my view seems to have been (incredibly eloquently, if I may add) by the commentators above. Nevertheless, I must chip in with my two cents, liberty with the facts is necessary sometimes in order for the film to avoid a downwards trajectory due to adherence to the facts (for example, the recent ‘Unbroken’ completely wasting the fantastic dynamic between Jack O’Connell and Domhnall Gleeson due to the latter requiring to depart from the picture, and really bogging down the whole second half of the film)

This is a very effective critical analysis of film and its historical accuracy, as well as how film has immense power to manipulate the way the audience thinks, feels, and interprets history. When films are historically inaccurate it can be a hindrance and annoyance, but also shows artistic and creative freedom.

An interesting essay about some good movies. It is always enjoyable to question the accuracy of movies that make a stab at addressing an historical topic. Somehow a warning label needs to be inserted at the beginning of these movie saying, “This is just a movie, entertainment matters more than accuracy. Enjoy.”