What Mothers? Mother Figures in The Magic Toyshop

In most fairy tales, the figure of the mother is absent. For instance, the mother in Little Red Riding Hood only appears at the beginning and takes no major part in the story. In other works, the good mother dies and she is replaced by an evil stepmother who terrorizes the protagonist. The child left alone has to take on the role of the mother, like Snow White or Cinderella, performing all its expected duties. But there is always a need to replace the mother, whether it is with the fairy godmother or the promise of a new family when marrying Prince Charming.

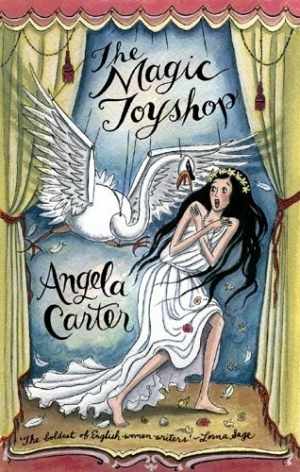

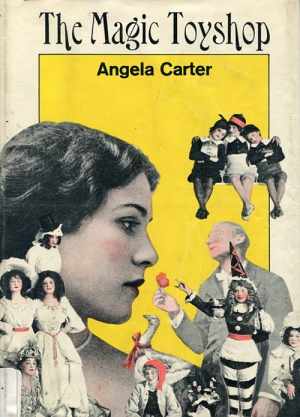

In The Magic Toyshop, Angela Carter cultivates this literary tradition with the story of Melanie, who loses both her parents in a tragic accident and is sent with her siblings to their evil uncle’s house. Throughout the novel, many characters appeal to motherhood in a patriarchal world where femininity is repressed, and most of them become substitutes for Melanie’s mother. Each character performs motherhood in his or her own way which highlights the need for mothers and the connotations associated with that figure. But in the book, motherhood also denied or made inaccessible by the patriarchal society which eventually leads to the loss of the mother. This impacts the child and his interaction with the social structure that surrounds him and that he has to accept. Therefore there is a need for the child to find an alternative mother figure to challenge the overpowering masculinity described in the novel.

The Need for Mothers: Connotations, Symbols and Challenges

Traditionally, mothers are the pillars of humanity – not only do they maintain procreation, they also provide the love children need to grow up. The figure of the mother is idealised by the child as she becomes the centre of his universe; his survival depends on her. A bondage is created during pregnancy and continues later through childhood and adolescence. ‘The ideal mother defines herself as a giver and a feeder, takes her existence and sense of purpose entirely from giving’, says Iris Marion Young 1. There is a sense of sacrifice in her giving hence her status becomes sacred, ‘wrapped up in some weird kind of holiness’ says Luce Irigaray. 2. She is ready to do anything to protect her infant, and provides basic needs like feeding, changing, bathing and nursing. Irigaray states that:

The maternal function underpins the social order and the order of desire, but it is always kept in a dimension of need. […] the role of the maternal-feminine power is often nullified in the satisfying of individual and collective needs’.

Thus the maternal is at the core of society’s foundation, but it is only apprehended on the level of basic needs – women cannot live outside their roles as feeders and carers.

Culturally, the role of mothers is to provide education to the new generation and build a sense of identity into their children. They also serve as mediators between the child and the external world and shape his social and cultural understanding of it. ‘Early interactions with caretakers become the foundations for beliefs, attitudes, and expectations about the self. When the primary caretaker is the mother, it is in the mother-child relationship that the self is born’ 3. Thus she prepares the child to evolve into the patriarchal world and teaches him its associated codes, from clothing to sexuality.

This is illustrated in the first chapter of Carter’s book, where Melanie experiments with her body and develops her sexual identity. Melanie’s imagining of her future husband demonstrates how culturally determined she is to embrace marriage.

She gift-wrapped herself for a phantom bridegroom taking a shower and cleaning his teeth in an extra-dimensional bathroom-of-the-future in honeymoon Cannes. Or Venice. Or Miami Beach. She conjured him so intensely to leap the space time barrier between them that she could almost feel his breath on her cheek and his voice husking ‘darling’. (Carter, 2) 4

Through her mother’s wedding dress, Melanie anticipates her role as a wife and mother. The dress is passed from mother to daughter, a symbol associated to the institutionalised society where marriage and parenting become social commandments. Thus the mother, through her belongings, helps construct the social and sexual identity of her daughter; but what is uncommon here is that it is Melanie who takes the dress in secret and embraces those gender expectations in the absence of her mother. This tells us more about the mother herself as Carter depicts a new type of woman who takes distances with her maternal position.

Melanie’s mother remains mysterious throughout the novel. We never meet her, never learn her name and she never directly speaks – we only get glimpses of her through photographs, objects around the house and Melanie’s recollections. She resembles the mother in Little Red Riding Hood, who pushes her daughter on the path of growing up but leaves her on her own from the start. She is often depicted through her clothes: ‘Her mother, in particular, was an emphatically clothed woman, clothed all over […] ready for some outing’ (10). It is easy to imagine her as an over-clothed, independent middle-class woman, concerned about her appearance and her social life. ‘When […] her mother cuddled her, the embraces were always thickly muffled in cloth’ (10). Here, her clothes become a barrier that disconnects Melanie from her mother’s tenderness. Are clothes used here as a protection, a way to distance herself from her role as a mother?

She leaves Melanie, Victoria and Jonathon to the nanny who treats them like her own children. For instance, while Mrs. Rundle knits clothes for the children, their mother has her own dressmaker and presumably buys their clothes. Melanie never talks about her mother’s cooking, and says that her mother ‘loved bathrooms’ (57). Thus she doesn’t incarnate the traditional connotations assigned to motherhood but is instead very concerned about her image as a feminine woman. Carter steps out of the traditional mother-daughter relationship and already sets the distance between Melanie and her mother which foreshadows her loss.

The Mother Figure Under Patriarchal Rule: From Denial to Loss

The denial of the mother figure is a way for the masculine world to monopolise social control. The mother is not desired but she is needed for procreation; after raising the children, man censures her body. Irigaray states that the primary sacrifice of the mother has been rooted within western culture since Ancient Greece. ‘The social order, our culture…want it this way: the mother must remain forbidden, excluded. The father forbids the bodily encounter with the mother'(Irigaray, 536). Thus a woman’s desire is forbidden by the Law of the Father which envisions mothers as threatening monsters associated to madness and death. Western culture is not founded on parricide but on matricide. Hence the father figure keeps its value, while the mother is brushed aside. She is restrained because of the special bond with her child, which represents a major cultural taboo.

For Cixous, the Freudian theory states that there is essentially one male libido and that the first object of love is the mother. The son and the daughter both desire the mother, but in the case of the daughter it is unnatural, an ‘anatomical defectiveness’ 5 thus it must be stifled. Cixous echoes Irigaray’s reading of the matricide, where the mother is blamed for the rise of decadence and has to be repressed. ‘Torn apart between son and father’ (Irigaray, 535) she is fragmented into pieces and therefore unable to articulate her difference.

With the loss of the mother, patriarchal rule becomes the ultimate sovereign and immobilizes women. Cixous argues that ‘in the extreme the world of “being” can function to the exclusion of the mother. No need for mother – provided that there is something of the maternal: and it is the father then who acts as – is – the mother. Either the woman is passive; or she doesn’t exist’ (360). The father becomes the ultimate figure of power and preserves a masculine genealogy within society, replacing the mother with his authority. The son desires the mother but tries to liberate himself from this bond in order to dominate his sexuality and women’s actions. She has to disappear in order to fully accomplish manhood. This is reiterated in Iris Marion Young’s theory:

“Such patriarchal propriety in women’s bodies maybe unconsciously motivated by a desire to gain control over himself by mastering the mother.” But sexual desire for the mother must be repressed in order to prepare the man for separation from femininity and entrance into the male bond through which women are exchanged. (159)

After replacing the mother and mastering his sexuality, the father becomes a sort of fake mother – he gives birth to a world built on his own reflection. Carter illustrates this point through the character of Uncle Philip, the anti-mother. He is presented as the binary opposite of the rest of the family and of the mother; in the wedding photograph, his face is blank in contrast with the smiling people. Melanie uses words linked to oppression and patriarchy to describe his dominating behaviour – his ‘immense, overwhelming figure of man’ (Carter, 69), his ‘shirt-sleeved, patriarchal majesty and his spreading, black waistcoat’ (73). She calls him ‘The Beast of the Apocalypse’ (77) as if he impersonated a demon who annihilates the feminine world. She adds that ‘his authority was stifling (73)’; ‘his presence, brooding and oppressive, filled the house’ (92). Melanie trembles at the thought of being constantly watched and supervised – she is conscious of the restrictions imposed on her as a woman.

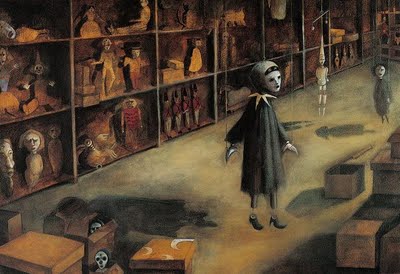

Uncle Philip is also a creator – he builds puppets and uses them in his shows. ‘”He is a master” said Finn, “There is no one like him, for art or craft” ‘ (64). Uncle Philip also moulds the members in his house and places them under his control in his own live-show. He takes Finn and Jonathon as apprentices, forbids women to wear trousers and even uses Melanie as a human puppet in his show. Mirrors are prevented as the characters are not allowed to shape their own appearance – they are meant to accept Uncle Philip’s vision. Margaret remains silent and never revolts against her situation, thus she is metamorphosed into Philip’s doll – he selects the clothes and jewelry she wears, decides when they make love and assigns her to the kitchen. He even controls human interactions and tries to force Finn to make love to Melanie. Thus the household becomes a stage and Uncle Philip is its sole director; he performs virility by crushing all that represents the feminine. For example, he disdains Melanie’s father as he envisions him as emasculated. Where Melanie sees her father’s intelligence as a proof of masculinity, Philip praises manual work and strength, and completely discredits him. He suppresses him like he rejects his sister- they both represent the mother’s side, the ‘other’ that needs to be bridled. Hence Philip illustrates this fake-mother stage where the father forces the feminine side to become part of the world he has created. Irigaray points out the main problem of this masculine appropriation:

By denying the mother her generative power and by wanting to be the sole creator, the Father, […] superimposes […] a universe of language and symbols which cannot take root in it except as in the form of that which makes a hole in the bellies of women and in the site of their identity. (Irigaray, 537)

Thus the loss of the mother has considerable impact on womanhood but also on the stability of the children. If she is the carer, the feeder and the sculptor of his inner-entity, then her absence unleashes deep sexual and social instabilities within the child’s coming of age.

The Mother Is Gone: Repercussions on the Child’s Development

The loss of the mother compromises the children’s journey towards adulthood as the father takes control of their path and inhibits their feminine side. This is especially destructive for the daughter, who according to Freud takes her mother as a model and tries to reproduce her body. Cixous argues that if the body of the mother disappears, then the daughter has no access to femininity therefore develops a deranged sexual and social entity. As Judith Ruskay Rabinor poses, ‘Devaluing the mother and imposing unrealistic standards for mothering can cause confusion and despair in the daughter’s own journey through womanhood’ (237). The separation with the mother must be done at the right time, when the daughter is ready to evolve in the world of adults and share her love with the opposite sex. Iris Marion Young states that ‘a woman’s infantile eroticism in relation to her mother must be broken in order to awaken her heterosexual desire’ (159). But if it is removed unnaturally, if the mother disappears from the daughter’s life too early, then the child’s development of a sexual identity is disturbed.

Carter explores the effects of the lost mother on the children’s psychological and sexual identities mainly through Melanie. The wedding dress symbolically foreshadows the loss of the mother and the mental repercussions on Melanie’s identity. Even before the announcement of the accident, Melanie feels something is wrong with the dress – she is too skinny for it. ‘She was bitterly disappointed that the dress was too big’ (Carter, 16). This shows that Melanie is too young to become a wife and mother. The fact that she has taken the dress secretly, not following the tradition, already suggests disorder; Melanie, too impatient, should have waited for her mother to give her the dress at the right time, when she would have been ready to assume the feminine role. Thus the mother-daughter transmission has failed and the mother has been removed unnaturally.

This leads to a feeling of guilt as Melanie blames herself for her parents’ death. ‘It is my fault because I wore the dress. If I hadn’t spoiled her dress, everything would be all right (24)’. Later on, she calls herself ‘the girl who killed her mother’ (24). The brutal loss of the mother has created a feeling of shame and guilt in the daughter which distorts her natural maturing and makes her depreciate her femininity. Melanie tries to recreate her mother’s presence by wearing her make-up and her perfume; ‘there was an oppressive stench of Chanel No. 5 from a litter of broken bottles. […] Covered with lipstick and mascara, her face was a formalised mask of crimson and black’ (26). By wearing all that represents femininity, Melanie tries to fill in the emptiness left by her mother. She unleashes her anger and tries to incarnate her mother, which overshadows her own personality and prevents her from blossoming into an independent woman.

In the next stage, Melanie tries to detach herself emotionally from her mother. ‘Mummy. No, Mother. Now she was dead, give her the honourable name, “Mother” ‘(32). Here the mother is envisioned through her status but is no longer tied to the emotional side of the daughter. Thus Melanie tries to progress through her transformation to womanhood by overcoming the suddenness of the mother’s loss and making it a voluntary separation, an attempt to regain control over her sexual growth. But the unnatural loss of the mother keeps disorienting the children, and in Carter’s novel leads to incest. At first, Melanie is repulsed by Finn’s attempts to kiss her (her ‘uncle-in-law’) but she quickly surrenders and believes they are meant to be together. Thrown into the sexual encounter with the man, she is forced to believe he is the one, whereas we are never sure she truly loves him.

Her mother being absent, she cannot share her experience with her and ask advice. Margaret is of no help – she has lost her mother at an early age and therefore did not get a maternal perspective on sexual matters. Completely repressed by her husband, Margaret has developed an unnatural lust for Francie. Francie and Finn were not able to detach themselves from their desire for the mother, thus they always carry this desire with them; Finn projects it on Melanie, and Francie on his sister Margaret. Hence Carter argues that the premature loss of the mother provokes sexual instabilities; but these lead to the need for the child to replace the mother with a substitute and, for the daughter, to become a mother herself.

The Need to Replace the Mother: Transposed Mother Figures

As the mother is essential, the children try to find a way to replace her and fill in the emptiness left by her loss. Even socially, it is expected to replace the mother – the son takes a wife and the daughter becomes a mother herself. Irigaray says that in the absence of any representation of the mother, there is a constant danger of going back to the primal womb and seeking refuge in any open body, in the bodies of other women, just like Finn and Francie try to access their mother through Melanie and Margaret’s bodies. Hence it is necessary to find a successor to the mother. In The Magic Toyshop, Mrs. Rundle, Margaret and Melanie herself become substitutes for Melanie’s mother. Mrs. Rundle acts as the traditional housewife and mother – loving and caring, she provides the children with basic needs and fulfil the role left by the absent mother. If we go back to the connotations associated to motherhood like providing food, clothes and protection, Mrs. Rundle accomplish them all perfectly, and Melanie refers to her as the ‘mother-hen’ (29). For instance, Sarah Sceats argues that:

Food is a currency of love and desire, a medium of expression and communication[…] For many people the connection of food with love centres on the mother, as a rule the most important figure in an infant’s world, able to give or withhold everything that sustains, nourishes, fulfils, completes. It is this person who shapes or socialises a child’s appetite and expectations of the world.

Mrs. Rundle shows her love to the children by overfeeding them with bread-pudding that she bakes herself with ‘extraordinary virtuosity’ (Carter, 3). Hence she takes on the role of the feeder and suits the social stereotype of the cooking mother. She also knits sweaters for them at Christmas when they are at their Uncle’s house. The sweater ‘seemed to warm her [Melanie] with more than wool, as if Mrs. Rundle had purled and plained some of her love into it with every stitch’ (160). Here, the sweater shows how Mrs. Rundle provides more than clothes but also comfort to the orphans, which makes her an adequate mother figure. She seems even more committed to it as she embraces its traditional connotations and knits the sweater herself, unlike Melanie’s mother who has a dressmaker. She sings lullabies to Victoria and is ready to protect the house from anything, ‘brandishing the poker she kept beside the bed to deal with burglars in the night'(17). Thus the nanny becomes the feeder, carer and protector of the children and fully embraces motherhood in the absence of Melanie’s real mother.

Margaret also acts as a replacing mother for the children. Her special bond with Victoria releases her maternal instinct; ‘Aunt Margaret wanted babies so much, she wanted Victoria for her very own’ (78). Throughout the novel, she overfeeds Victoria to compensate for her loss and give her the love she needs; ‘She became fatter […] Aunt Margaret spoiled her and adored her’ (88). Margaret welcomes the children with food described in comforting terms: ‘a steaming and savoury pie’, ‘white bread and brown bread, yellows curls of the best butter, two kinds of jam […] and currant cake’ (47). Despite being constantly repressed, Margaret tries to create a homely environment evoking the maternal archetype.

When Melanie faints, Margaret feels a real motherly distress, and Melanie comes to see her and Francie as surrogate parents. ‘He and his sister stood on either side of the bed, bending over her as if to protect her from the perils of the night with their own flesh and bone’ (122). When Margaret caresses Melanie’s cheek, she imagines her own mother: ‘Then she smiled, stroking Melanie’s face again, so tenderly that Melanie closed her eyes and imagined it was her own mother caressing her’ (122). Hence Carter makes of Margaret a substitute mother needed by the children to re-access their feminine side and oppose Philip.

After her mother’s death, Melanie feels it is her duty to take care of her siblings and to become a surrogate mother. Mrs. Rundle keeps saying she needs to be ‘a little mother to them’ (28). ‘I am responsible […] I am no longer a free agent […] The burden is all mine’ (31). Melanie associates motherhood to containment and responsibilities – with the brutal loss of the mother, she forfeits her childish innocence. When she is with Finn, she realises that ‘they might have been married for years and Victoria their baby’ (177), a prophetic vision of her future role. Thus the daughter needs to become a mother – but through Carter’s feminist viewpoint, she becomes one in order to recreate the lost mother-child bondage hence re-establishing the feminine side within the next generation. To replace the mother with other women or with the daughter is to perpetuate a maternal genealogy, to regain control over the child and help him grow up. It is needed in order to restore the natural stability between both sexes. Thus the feminine frees itself from the dominance of the father.

Conclusion: Redefining and Re-empowering the Mother

Carter’s novel can be regarded as the feminist rewriting of a fairy tale, where the essential figure of the mother is absent due to the rise of patriarchal rule. Her loss creates sexual and identity instabilities in the child who is subject to the Law of the Father where men like Philip create a world to their image. Yet the negative effects on the child’s development reinforces the need to find substitutes to the mother, just as Melanie finds in Mrs. Rundle and Margaret surrogate mothers. But she is also pushed to become one herself in order to re-access her feminine side and contest patriarchy. Thus Carter suggests the re-empowering of women through a redefinition of mother figures.

Works Cited

- Young, Iris Marion. “Breasted Experience: The Look and the Feeling.” On Female Body Experience: Throwing Like a Girl and Other Essays. Ed. Iris Marion Young. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2005. 75 – 96. Print. ↩

- Irigaray, Luce ‘The Bodily Encounter with the Mother’. taken from Lodge, David and Wood Nigel, Modern Criticism and Theory third edition., UK: Pearson Education Limited, 2008. (pages) Print. ↩

- Ruskay Rabinor, Judith. “Honoring the Mother-Daughter Relationship.” Feminist Perspectives on Eating Disorder. Ed. Fallon, Patricia, Katzman, Melanie and Wooley, Susan. New York: The Guilford Press, 1994. 272. Print. ↩

- Carter, Angela. The Magic Toyshop. Great Britain: Virago Press, 1981. Print. ↩

- Cixous, Hélène. ‘Sorties’. Taken from Lodge, David and Wood Nigel, Modern Criticism and Theory third edition. UK: Pearson Education Limited, 2008. (pages) Print. ↩

What do you think? Leave a comment.

I had a gut feeling that Angela Carter would become of my new favorite authors after reading this book and I was not wrong.

I really loved The Bloody Chamber, and I do like Carter’s writing, but didn’t like this one. Good writers have written some of my least favorite books, precisely BECAUSE they are so good at their writing. Such is the case here.

I have to say, Finn is an extraordinarily creepy leading man. I don’t think Carter wants us necessarily to root for them as a couple.

I love Angela Carter from what I’ve read of The Bloody Chamber, so kudos on this incredibly thorough post!

Carter’s writing is so descriptive and evocative that you feel as if you’re an extra in a film and experiencing every sensation and emotion she describes.

Nice article but I must admit this was a difficult read. It was a very uninvolving book with characters that I found hard to feel any emotion for.

This one echoes poetry throughout. I was completely taken in when reading it.

Thanks for sharing, enjoyed it a lot. I have Burning Your Boats on my shelf right now which I’m reading next.

Carter and no fairytale. I don’t buy it!

I love that it’s from the point of view of a child teetering on adulthood– in a way, it’s a coming-of-age story–in an unsavory environment.

A completely brilliant read.

This was one of my books for my university reading list, so I was sort of expecting something non-controversial, non provocative.. Boy, was I wrong. I wish the ending had been more drawn out. It was really bizarre, and I felt I needed more time to get used to Margeret and Francie before the abrupt ending. Maybe that was the whole point. Anyway, lovely article!

Great essay. I can understand why it is a classic and something that can be read and reread again and again.

I found Melanie’s passivity and eagerness to embrace womenhood to be irritating. She has flashforwards to them as a couple with a brood of redheaded children and she is discomforted by this, but then she goes along with it anyway.

Awesome read!

While reading this article all I could hear was “Just A Girl”- No Doubt running through my mind.

“Don’t you think I know exactly where I stand

This world is forcing me to hold your hand..”

Thanks for this interesting thought regarding the role mothers or lack thereof play in fairytales.

The way that Carter strings together words in such an eloquently made fashion is truly magical.

What’s better than feminist fairy tales?!

Carter writes with such honesty about what goes through the mind of an adolescent.

I was surprised because I thought it would literally be about a MAGIC toyshop.

This has a great feminist subtext.

It’s an extraordinarily oppressive book!

Angela is a master at combining fantastical whimsy with the disturbing realities

I really like the wistful way that Carter seems to write.

It is really wonderfully well written and a story that will stay and stay with one, because of its complexity.

It is by far one of my most favorite books.

carter has a great way describing setting and scene.

I used to read Angela Carter way back when, oh, probably the 90s. I was really take with her macabre style and coldly calculating prose. She was a good, dark read, and she used to clobber you in the guts with her twists and turn of phrase.

Carter has a way of giving you the chills when she describes Melanie in her mother’s wedding dress doesn’t she!

A look into our souls…

Interesting article. There is plenty of material on what happens to real and fictional children who grow up motherless, but this is one of the first articles I’ve seen that talks about the “denial” of the mother figure. In many ways, an existing but passive mother might be worse than no mother at all, as your examples and analysis of mothers in the patriarchy clearly demonstrate. Historically accurate though this is, it’s always depressing to think that mothers are “not [desired, but] needed for procreation.” I wonder if, subconsciously, that’s why so many writers dispense with the mother or don’t let her take an active role. That is, the writers explore the mothers’ feelings of, “I’m not needed here, so I’m going to disappear or at least shut up.”

I think that what can be shown here is that when someone is deprived of a necessity, the deprived attempts to recreate or reconstitute it, sand the result will be something far inferior to the original.