Duality of American and Japanese Animation

Animation is animation, no matter where it comes from, or how it’s made. Yet in the sprawling jungles of the North American animation fanbases, there seems to not only be a misconception that anime and cartoons are different mediums, but that one must be superior to the other. While the latter is up to subjectivity and former is objectively untrue, there are reasons for such beliefs.

When it comes to animation, the U.S and Japan are the two biggest producers within the medium. You rarely ever hear animated works discussed outside the two, even when countries such as France, Britain, Ireland, Mexico, China, etc. have a presence in it themselves. Many people like to argue whether cartoons or anime are better, which is usually one of those heated debates where nobody really changes their mind.

First things first, anime and cartoons are the exact same thing. Anime is merely the Japanese term for cartoon. One Punch Man or Kill la Kill aren’t any less a cartoon than a show such as The Simpsons or Tom & Jerry. The advent of anime-inspired western cartoons such as Totally Spies, Teen Titans, Avatar: The Last Airbender, The Boondocks, etc. have also blurred the lines between how fans categorize what is and isn’t anime.

Those unfamiliar with Japanese anime, especially U.S audiences, will naturally prefer western cartoons due to environmental upbringings, cultural disconnect, anime stereotypes/tropes, the medium’s incestuous and homogenous visuals, etc. Meanwhile, anime elitists like to point at U.S animation’s saturated history of cartoons made only to sell toys, rarely appealing to demographics outside of young children, lack of risks and innovation in their storytelling, etc. Both sides have some valid criticisms for the other, but both also are often very biased and generalize the other as well.

Many non-anime fans either don’t watch any anime or only expose themselves to the more accessible, mass appealing shows such as One Punch Man, Death Note, Cowboy Bepop, Studio Ghibli films, etc, often saying how these shows or movies don’t “act like anime” (a notion I personally don’t like) or don’t adhere to the generalized conventions that many anime use.

Anime elitists, in turn, cite that all U.S cartoons are for kids, not only rarely aiming outside the realm of comedy, but resorting to the lowest facets of entertainment, i.e fart jokes, talking animal sidekicks, wacky catchphrases, shallow characters, etc.

Stereotypes exist for a reason, but they also emerge from ignorance. These generalizations stem from lack of exposure, with most people on both sides often being exposed to the most surface level of one than the other.

Just like any medium, animation encompasses a wide variety of genres and narratives, and despite perception within the geek culture shifting, is still stigmatized by the general public. Nobody goes into a bookstore and is surprised to see different books about cooking, fantasy, sci-fi, thriller, mystery, advice, education, action/adventure, etc. It’s widely accepted that novels are a medium that explores a wide range of topics and genres, but unfortunately, such isn’t the case for animation, despite it being true.

Yet even within the fanbases of the medium, there’s still division, especially when it comes to U.S and Japanese animation.

There’s a great quote from an online blogpost by an author named tamerlane: “The Americans and the Japanese are the two biggest representatives of mainstream narrative animation, yet they differ so radically in their understanding of the medium that it’s impossible for us to judge one by the standards of the other”.

People often don’t realize that while both are animation, they still come from different histories and cultures, and thus their modes of production, storytelling, and perception will be different. They assume that what they like from one must be present in the other, and thus reject it when their expectations aren’t met.

History and Techniques

Identifying the similarities and differences between the two calls for looking at the historical context in which both systems emerged: the Golden Age of U.S animation. It’s no surprise that most people are still unaware that early anime was inspired by Disney and the early Hollywood cartoons in general. Hollywood cartoons echoed the live action film emphasis on performance in the 20s to the 50s.

In American animation, the animator is the actor bringing inanimate objects to life. When Disney set out to create the first feature-length, cel-animated movie, the focus wasn’t on camerawork, the sets, or staging but how they would bring about characters like Snow White and Grumpy to be lifelike and connect with audiences as if they were real actors.

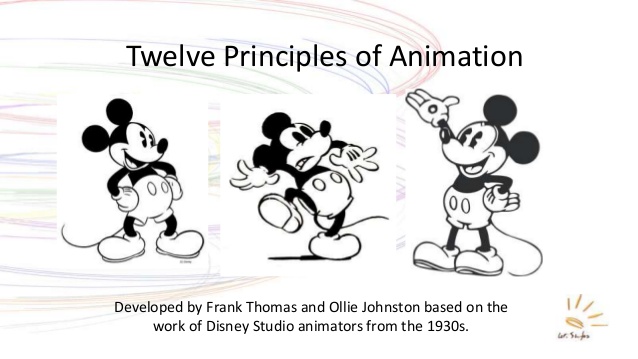

American and Japanese animation productions do not animate the same, the former using full animation and the latter limited animation. Full animation is defined as animating on the 1s or 2s, meaning that for every second of a 24ps animation, there are 1 or 2 drawings. This foundation developed into the 12 Principles of Animation, some of which include squash and stretch, secondary action, follow through, and moving holds.

These techniques cement the illusion that animated characters exist in a consistent version of reality, and that the audience don’t see the characters as animation. Disney’s standard was to create the illusion of life, hence no style changes as that would break the illusion. The standard was based on the animators being the actors. They watched and studied real-life objects, people, animals, etc. and emulated their movements on paper.

On the other hand, anime focuses more on character acting being symbolic. Rather than actors, Japanese animators act more as filmmakers using limited animation, which reduces the number of frames per second, usually about eight.

With limited animation, anime reuses common parts between frames rather than redrawing. Despite the influence Disney animators had on the anime pioneers, Japanese animation quickly diverged, with less emphasis on fluid character movement and more on composition and experimenting with camera movement to make the image appear more dynamic.

These differences in which the fundamentals were removed is a common criticism of the medium from the American perspective. Japan’s differing view involves learning how to animate by quantity, rather than mastering the fundamentals. Early Disney’s hierarchy required rigorous time and work for an inbetweener to elevate to a key animator, contrasted with the same process being more streamlined in Japan.

However, it should be noted that limited animation is not only reserved within anime productions. Outside of Japan, the technique’s use was likely most widely seen from studios such as MGM Animation, United Productions of America, and most notably, Hanna Barbera. Following WWII, they sought to contrast themselves from Disney but ultimately used it to save time and money.

The technique can be targeted as being lazy, but contrarily, a strength is that it emphasizes voice acting and writing to accommodate for minimal visuals. Another difference between these cartoons and Japanese ones is the use of cel layers, whereas Japanese animation simply reuses the cels altogether. Lower quality isn’t automatically an indicator of limited animation, as its timesaving techniques can allow for a higher flow of keyframes and overall presentation.

The most significant example of this can be seen from Japanese “sakuga”. The term itself is Japanese for “drawing pictures” and refers to animation itself. However, in an anime context it describes moments in an anime when the animation goes from standard to being exceptionally fluid and expressive.

This technique is the very foundation for the sharpest visual contrasts between Japanese and American animation, one that goes back to the earliest days of anime. An example is a 1929 animated adaption of the Japanese folktale Kobu-tori, which is focused on a woodsman with a large growth on his jaw who finds himself surrounded by magical creatures. Notice how detailed the characters are.

Using limited animation grants animators to emphasize detail in character designs, while full animation focuses more on character expression and movement. This is why anime often features characters with more detailed designs while American animated characters often look more cartoony and drawn from basic shapes.

Unfortunately, like any technique, it can be used for animated productions overseen more from corporate perspectives, in which output is generated at the expense of quality and in favor of advertising.

This is exemplified by what became known as Saturday morning cartoons, which were defined by their limited animation and a result of children shows being restricted by parents and networks alike in their content (with some exceptions).

All in all, it’s merely a technique in which its effects are seen by the user and their intentions, Some of Chuck Jones’ cartoons in the 50s had their artistic look facilitated by limited animation than the traditional kind. Even Disney isn’t exempt from this. The movement in the 5 minute sequence “Ave Maria” of Fantasia is done by camera.

Anime’s American Influenced Origins

Many critics of anime often cite the medium’s differences from American animation as being more of a “slideshow” than actual movement, and more mainstream audiences believing it has no relation to the American animation industry. This dismisses the fact that Japanese animation found its roots in American animation, as the anime pioneers sought out the American animation techniques. Such examples include Yasuo Ōtsuka, who worked in Toei Animation and Studio Ghibli, studied the US animation textbook by Preston Blair and Yaiji Yabushita went overseas as a research trip before Toei was set up.

Divergence from Disney still didn’t equate to divergence from western influence, as Warner and UPA were inspirations for Makoto Nagasawa. A 1931 anime short called “Ugokie Kori no Tatehiki” is styled to the resemblance of Max Fleischer and Otto Messmer. Even Miyazaki himself, the harshest Disney critic at Toei, enjoyed the Fleischers.

Industry-Based Differences

The Japanese animation industry’s divergence from its primary western influences paved a path for its own way of doing things, but that divergence doesn’t mean it’s inferior on a technical level. Japanese animators serve more as cinematographers than actors, addressing how a scene is shot, choreographed, and how subjects move in-frame.

If a Japanese animator is assigned a scene of a character tapping their fingers on a desk, rather than asking how they use the action to reveal the character’s personality or thoughts, they ask “How should the fingers look or move while tapping the desk?”

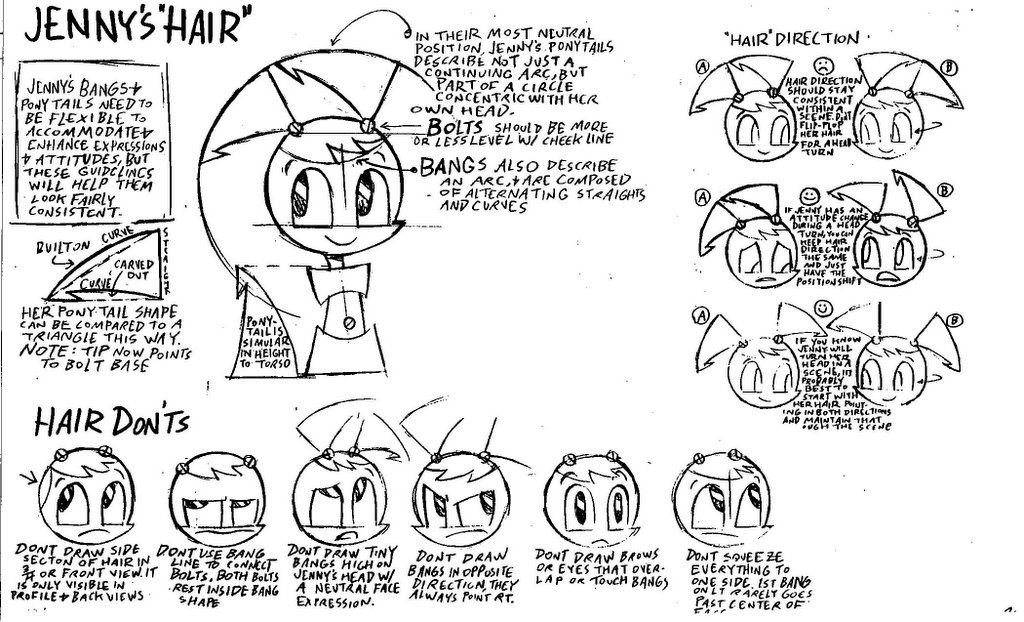

The decentralization of Japan’s animation industry provides animators more creative freedom to experiment and be distinctive, whereas in most US animation pipelines, the animation is more standardized and compact. Key animators being required to design their own layouts effects how they conceptualize their work.

From Yoh Yoshinari handling the digital post-production of his cuts to animators like Yutaka Nakamura choreographing their own fights in place of the director, Japanese animation’s reliance on small studios, subcontractors, and freelancers that outnumber large corporations incentivizes artists to think of their own scene or episode than the show as a whole.

This is why in Japanese animation and US animation fan circles, individual animators are generally more acknowledged in the former whereas it seems animators must be Disney/Pixar directors or TV animation creators to be mentioned in the latter.

Consistency is still present under deadlines rather than monetary constraints, which is counter measured by the “sakkan” or animation director, who oversees a project’s key frames. But the most significant development in anime was removing the distinction between character, background, and effects. With Japanese animators being cinematographers, everything that can be filmed must be their subject.

This can create flashy action scenes, but just as the best of US animation, the best of sakuga can depict the detail of what a character feels, not how they act.

Both US and Japanese animation have their own distinct beauties and, depending on who’s asked, drawbacks. With anime being deliberate and demanding a visceral reaction, whereas U.S animation seeks to be appear effortless and graceful, it’s no wonder the reception between the two differs so much. However, the distinction seems to run up to corporate management as well.

Both are obviously managed by studios striving for profitable products (anime also relies on pre-existing IPs in the form of manga and the cooperation of various production committees, but that’s a different topic), but the anime industry’s storytelling feats is primarily driven by its makers.

In contrast, most of U.S animation has been produced by studios who see the medium as a means of selling toys, often seeking projects aimed at younger demographics, and thus perpetuating the stigma that animation is plagued with today. In other words, because many execs in American studios don’t seem respect the medium, their products cause audiences to not to as well.

The medium’s perception has shifted significantly among niche, geek fanbases, and though there have been breakthroughs in animated film and TV, general audiences still refuse to take it seriously as any other medium.

Fortunately, the rise of digital media and globalization has allowed more innovation. Netflix has been investing heavily into animated content, especially with anime, while anime productions have recently invested in foreign, non-Japanese animators and creators.

There’s nothing wrong with preferences, but I urge anyone with prejudices towards either Japanese, U.S, or any animation to look beyond their generalizations and try to see what animation can and has offered. Subjectivity is intrinsic to interpreting art, but I believe it disingenuous to say that animation, American, Japanese, or any other, hasn’t impacted pop culture to the way we see it today.

Disclaimer: I refer to “U.S animation” rather than the umbrella term “western animation”, as I don’t have enough extensive knowledge of animation’s history in western countries outside the United States.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

When we say anime we understand a specific style of animation. A style common only for a certain region of the world.

I see where you’re coming from, however, if you’re referring to the art styles present, I think calling it a “style” is disingenuous and implies that there’s only one art style in anime. While it’s very homogenous, anime still has different art styles within it just as U.S cartoons do.

Miyazaki’s style isn’t the same as Osamu Tezuka’s, Tezuka’s isn’t the same as Hideaki Anno’s, whose isn’t the same as Katsuhiro Otomo’s, etc.

If you’re talking about how it’s created through limited animation and sakuga, then sure. Anime outside of Japan is referred to Japanese animation, but my point is that they’re still cartoons regardless. It’s all animated.

Same with manga vs western comics.

If you look at most western animation and compare them to most asian animation, It is noticiably different. Like the difference between western rpgs and jrpgs, there is a difference. How much this difference means to you is up to the person in question.

There’s also different cultural understandings of cartoons. Like cartoons are for children. This is because in America at least cartoons are primarily aimed at children, but this isn’t always the same elsewhere. This type of thinking leads a lot of people over here to think anime is a cartoon so therefore it is also for children.

However anime is for everyone.

It has several audiences including the shōnen (boys ages 12-18), shōjo (girls ages 12-18), kodomo (children), seinen (men ages 18-50), and jōsei (women ages 18-50). There’s even anime made for office people. The entire iyashikei genre is for people that like to relax after work. Even if you just went with the biggest audience for anime, it’s still shounen.

I don’t see how different cultural contexts make anime not cartoons. Anime is simply the Japanese term for animation.

One of the definitions of a cartoon is” a motion picture using animation techniques to photograph a sequence of drawings rather than real people or objects.” I don’t see how Japanese cartoons don’t apply to this as much as western cartoons do. If it’s animated, it’s a cartoon.

With that said, anime does have far more variety in its storytelling and demographics as you explained. I think anime had the advantage of not being held back by Puritan standards upheld by those who felt anything that wasn’t “child-friendly” was threatening or juvenile, unlike animation in the U.S. At least not to the same degree.

But don’t cartoons also have several audiences as well? There are those aimed at an adult audience such as The Simpsons, South Park, a couple of works by Seth McFarlane and animations on Netflix. Heck, I don’t think older cartoons were aimed at children, either, let alone exclusively aimed at children.

And I’m curious how that mindset of “cartoons are for children” persisted, when some of the shows I mentioned either have been running for decades or are classics. I think this mindset is a recent phenomenon.

You’re right, both American and Japanese cartoons encompass different genres and audiences as well. For the U.S, animation actually started off being aimed at adults as short films in movie theatres.

I’m still not completely on top of the history, but I do believe at some point animation’s transition from movie previews to TV created different standards, which included demographics. Studios didn’t want, or even couldn’t. spend as much money and resorted to cutting corners while making as much profit as possible.

They thus used animation as a means of ads to sell toys and merch for children, which created mandates they believed fit for child audiences. This included all the stereotypes of U.S animation I mentioned in the article.

The mindset has been around for quite a while. I’d say Hanna Barbera and ironically Disney is very guilty of this. HB’s Saturday Morning Cartoons convinced an entire generation of people that all animation is within that mold and an inferior art form to live action, and is only worthy of praise if it’s a feature done by Disney or Pixar.

Tom and jerry is anime in japan, any cartoon is anime there. Here in the west most people only consider it anime if it’s from japan. They don’t have that classification in japan.

The classification isn’t the same, that’s correct, however, anime, when referred outside of Japan, is still a cartoon, just with its production originating from Japan. If it’s animated, it’s a cartoon. A cartoon isn’t suddenly exempt from being a cartoon just because it’s from a different country.

Whenever someone asks me what’s anime, I tell them it’s Japanese cartoons. What else can I say?

Anime are cartoons.

With that said, saying cartoon has a connotation behind it, but so does anime. If you say cartoon someone will think childish, if you say anime, the “normies” will think perverted shit like hentai or DBZ/Pokemon.

The only reason why I see there being a difference is the connotation. But to avoid it all together you could just refer to it as animation, but I don’t really care anymore.

anime. -japan cartoon- the world

The fact that shows like Teen Titans and Avatar: The Last Airbender are often deemed anime-esque, if not anime outright, says a lot about what we associate with Japanese animation versus Western animation. There are plenty of actual children’s anime with chibi characters and animals, though not all such anime is necessarily for children. Either way, those shows rarely gain the same amount of traction as shōnen anime here in the West. It is instead the more serious, action-oriented anime that form the basis of the Western understanding of what anime is generally about. Even shows like Pokémon and Yu-Gi-Oh! which are often silly and, dare I say, childish, have plenty of serious moments that you would rarely, if ever, find in a show like Spongebob Squarepants or Phineas and Ferb.

In the anime community, traps are more or less a positive, or at least mostly neutral, thing. Outside? Its probably looked at as a derogatory term. Otaku is similar.

The quality and themes in anime are overall quite a bit more mature (with some exceptions) than that of what we commonly think of when it comes to cartoons (again with even fewer exceptions).

I see what you mean, but I think that depends on the anime. Most anime is targeted towards children, and just like U.S animation, the quality of an anime is subjective and its themes conveyed depends on the writers/directors.

With that said, Japanese animation statistically speaking has been far more ambitious in its storytelling as an industry compared to the U.S animation industry.

Great article

An important point you bring up is the growing variation and option pool in the global, digital market. As you establish in your article, Japanese animated works were more so a niche in the U. S. marketplace, but that interest has risen to become a sturdy foundation of taste. This development is concurrent to, in my view, the growing factionalism of taste and culture in the U. S., possibly the globe.

Even as the political landscape chafes under the two party system, consumers are turning away from a monolithic “mainstream” in favor of an eclectic personal palette. It is more difficult now to be a predominant pop star when a plethora of smaller scale musical outlets draw attention from smaller factions.

This societal development translated to greater respectability for both American and Japanese animation—smaller scale productions and material that would have been seen as abjectly odd 20 to 30 years ago now have audiences that justify their continued existence at the streaming baseline. As a result, animation as a medium, on either side of the Pacific, is respected as just such—a medium, rather than a genre for the kiddie matinee.

But, I digress. I appreciate your article, especially for the attention to detail in filmmaking language.

Thank you for the feedback, I’m glad you liked it!

I completely agree with you regarding the increasing globalization of animation, especially with Japanese animation. The internet has allowed for animated media, whether independent or industry-based, to be exposed to wider audiences through various outlets. Platforms such as YouTube, Newgrounds, Netflix, Hulu, etc. allow for these markets to rise and help put animation at the forefront.

Animation is definitely respected as a medium within the industry (by its creatives and I’m sure some executives) but unfortunately, it’s the opposite when it comes to many studios and general audiences. This stigma is a part of the reason many people deliberately refused to see Into the Spider-Verse, as it was a larger scale animated feature not done by Disney or Pixar, which I’m sure was off-putting to audiences not used to such a novelty.

Fortunately, animation is far more accessible than before. Places such as Netflix, Cartoon Saloon, Sony Imageworks, and a few anime production committees seem to be changing the landscape with more ambitious projects driven by diverse voices. This includes international efforts of animation studios and creators helping bring more innovation to the medium. I’m rooting for all of them.

Anime is a much broader genre in terms of subject matter. While western cartoons are almost exclusively created for and marketed to children, Anime often tackles much more adult themes and stories. Anime has a ton of sub genres. Something like Shounen, literally, “Boys Anime” are pretty close to western cartoons. Some examples of Shounen shows include Naruto, Sword Art Online, etc. But a vast majority of anime covers a lot more mature topics. Anime generally has much more character development, and more complicated stories and overarching themes. Unlike cartoons, almost all anime is marketed roughly towards the 16-26 age range, which is why the genre is so sexualized. Anime fans don’t want people to think they’re watching kids entertainment.

Personally, I think mislabelling anime as a genre is an aspect of the problem I see when people look at animation in general. I understand that anime tackles more mature subject matter more often than U.S cartoons, but the latter has its fair share of that as well, especially in the last decade.

U.S/western cartoons such as Batman TAS, Samurai Jack, Teen Titans, Avatar: TLA, Adventure Time, Hey Arnold, the DCAU shows, Regular Show, Steven Universe, Gravity Falls, The Breadwinner, etc. have all handled mature themes with serialized storytelling, and this trend is continuing.

Just because Japanese animation handles its stories differently overall doesn’t suddenly exempt them from being cartoons. The word “cartoon” may carry a childish connotation but that doesn’t change that they’re all animated, and thus cartoons regardless.

When you hear cartoon, you immediately think of western cartoons like adventure time or spongebob. And if you say anime you think of eastern cartoons like dragon ball or my hero academia.

Anime is cartoons, i dont think anyone denies that. We just use it seperate the two. Cartoon is used for western animations and anime is used for japanese. Yes they mean the same thing but as anime is quite different from western cartoons we like to keep them seperate

I understand separating them on principle, especially when looking at the different modes of production and subject matter. My point is that it’s all animation regardless and that a cartoon is a cartoon, no matter the location.

The word cartoon makes me think of kids watching Ben 10 or one of those cartoon network shows. It’s misleading to most and therefore others use it as a derogatory term to say anime is just for kids, of course it doesn’t feel right to me.

Anime just means animation and therefore it’s cartoons. But cartoons don’t necessarily have to be animations (they can be drawings or comics), while anime is by definition animation.

Animation is another fascinating movie media. What’s amazing is the fact that it’s dated from as far back as it is, and is often fascinating, colorful, and very lively. While American animation is often very cool, and is mostly done on computers these days, the Japanese animation has a different, and even more interesting quality to it, ranging from very gentle, to very harsh, rough-and-tough, and combat-ready characters-very peaceful to quite warlike, and in harsher lines than American animation.

i feel like too many people ignore what a word is used for vs fundamental meaning. sure a word could be intended for certain use by definition, but it has grown a certain meaning in certain cultures that the textbook definition isint the actual definition people use. yet people will still argue for the textbook definition despite how it is seen by the rest of the world. cartoon has very different connotations than anime does as a word.

I understand that, and you make a great point about definitions. Language is fluid, and a word’s textbook definition isn’t always the same as it’s used in certain contexts. But my point is that those connotations don’t change the fact that it’s all in the same medium.

Idk for anyone else, but for me I just consider cartoons animated tv from the west. Being incredibly clear, this does not include films for me. It is not a matter of strict definition but of culture, the trends and mindsets of those who work in animated film in the west are not the same as those who work in tv. They might as well be different mediums when talking about the two in any substantial way. As for anime (which I’ll just say is animated stuff from Japan. Obviously certain things create blurry lines yada yada, but that can be decided on a case by case basis. PSG is an anime lmao.) and cartoons, they’re written and animated absurdly differently. The culture, influences, intent, aesthetics, etc; are all incredibly different, and yes, this is true as a generalization. It has nothing to do with thinking one sounds childish or more childish than the other, in fact for myself I greatly prefer cartoons (or whatever you want to call western television animation lol) to anime. And functionally, it just makes sense to have different words for the two of them, and everyone already knows what you’re talking about.

I agree that the resources, production factors, and mindsets are different in animated film and animated TV, but I think it’s a stretch to say they’re in different mediums, but I digress. Using two separate terms does streamline things for conversations, I do agree with that as well.

Anime is a cartoon coming from JP and surroundings since the artstyle is totally different from Western, Cartoon is the one from the Western part.

Anime doesn’t have a single art style though. That’s like saying all Disney cartoons and every American TV cartoon all share the same art style.

People who get offended at anime being called cartoon get so because cartoon is seen as something targeted at kids and they dont wanna be seen as kids by people when anime targets a bigger audience than just kids.

I think the definition of cartoon is way different than what it used to be, Rick and Marty or Big Mouth are also Cartoons but no one would ever let their kids watch these shows in the morning cartoon Programme on TV.

The main reason, I believe, that people make claims such as, “anime and american cartoons are not the same thing,” is because, often, passionate people do not want to equate two things with certain differences because they are convinced that, by doing so, they are discrediting the medium in question as a source of quality, specifically if they prefer one over the other. They mistake similar quality with similar structure and purpose.

Agreed, and personally, I think that’s their problem if they hold those beliefs. There’s nothing wrong with preferences, but I don’t see how calling anime cartoons (when that’s what they are) discredits them just because of certain connotations founded on misinformed generalizations. Generalizations that are often made by people who either don’t respect animation or at least see it as an inferior art form.

Awesome look at the nuance of animation, very well written article! A thoroughly interesting analysis of the topic!

Thank you, glad you liked it!

I’m really impressed by your extensive knowledge and understanding of animation in America and Japan! I never even thought about the animators’ intents before and how different their animation techniques were. I just simply assumed, “One was more American, and the other was more Japanese.” Wonderful work on writing this article–I learned a lot!

This was a wonderful article, and very informative.

Impressive work and well done. As a long time fan of Japanese animation who had previously fallen into the trap of assuming it to be superior to anything the west can produce, I have to concede you’ve made your points very well. I stand corrected (or sit, as I’m having a cup of coffee right now). Great to see you’ve generated a good discussion as well.

I enjoy that this article makes a clear distinction that anime and cartoons are kin in the sense that they share an animated medium, and that there’s really no way to get around that. I’d be curious to hear more about the harem formula getting copy-pasted in so many mainstream contemporary anime (present in various classics as well!). I believe that it does a lot for initial Western interpretations of anime as being ‘perverted’ or lewd. Of course nay-sayers will argue for the blanket term “adult” in pro-anime arguments and “childish” applied to Western cartoons. Probably not a coincidence that when a show like Steven Universe comes out and tackles nuanced concepts such as sexuality and gender expression it’s framed as catering to SJWs or something silly like that. Whereas a universe in which NEETs and gamers are valuable, heroic protagonists are obviously perfect. Not me arguing against anime by any means because I’m a *huge* weeb, but it’s something I’ve observed in large capacities online.

I’m glad you enjoyed my article. I also agree with you regarding the double standards placed on U.S animation and Japanese animation. It seems due to Japanese animation’s long history of more ambitious storytelling compared to U.S cartoons, there’s either a sense of rejection or surprise when the latter does the same.

As you said, a lot of the rejection comes from a minority who are the loudest and complain about seeing topics such as sexuality or politics in U.S cartoons, despite many Japanese ones having and continuing to do the same.

It also comes from those, mostly adults and elderly folk, who look down on the medium as only kids’ entertainment and therefore become conflicted when their preconceptions of the medium are challenged.

I wouldn’t mind looking into the harem formula or general fanservice that exists in anime at all, as it’s one of the most common criticisms placed on it, especially from more casual viewers. Thanks for your input!

Anime incorporates an array of genres and is generally targeted towards mature and deeper content in terms of artistic style, story and character development- its much more complex. Thats why people are strongly against referring to anime as cartoons, since it has become directly associated to a medium that simply attracts a younger audience. I believe the word has become quite generalized and can barely be used to describe other animated sitcoms such as Rick and Morty or Bojack anymore yet alone anime. Either way, this article really did the job of cultivating idea and discussion.

The lines are definitely blurred by works such as “Avatar: The Last Airbender” – an animated series that uses a mixture of American and Eastern motion techniques, and one that also incorporates the many of the same story elements notably found in anime series’ such as “HunterxHunter” and several others. From the use of power-imbued youth to the insistence on self-mastery to obtain greater control and depth to personal power is central to both of these works of animation from a story-development standpoint.

I really enjoyed reading this article.

While I have always understood anime to be the colloquial term for Japanese animation, I can’t say that I will ever be able to consider cartoons and anime one and the same, simply because they can be put together under the umbrella term “animation”.

I believe that the author raises a good point in noting the different methods of (among other things) storytelling dependent on culture.

Anime has had a more profound impact on me than any Western cartoon I can name. As a result of this I feel uncomfortable with the comparison between shows like Deathnote and The Simpsons; I’m not sure that comparing the two to begin with is the right way to go about explaining that the two can, at least in one way, be can be considered the same.

Imagine being so triggered over people wanting to differentiate anime from cartoons that you make a huge article about it. if cartoons were truly the same as anime, people would naturally feel that way on their own without you needing to write a PR piece trying to convince people that this is the case.

Not saying cartoons are bad though. things like the disney classics(especially its artstyle) have their own charm to it that anime cannot replicate.

The only similarities that cartoons and anime have is that they are drawn. Other than that, when it comes to the types of stories, the story structure, tropes, character building etc. they are very different. And to be honest anime story structure, story telling and character building just has more depth than cartoons,

even when a cartoon is drawn in an anime style i can still tell that it was made by a westerner simply because of its way of story telling and character building and tropes.

the only ones from the west that have successfully managed to get the anime feel to it, are those who are made by either western born asians or westerners who are big weebs.

Is this what agenda in the animation world feels like?

The origins of the visual style of Anime can be linked to traditional woodblock prints from the Edo period known as ukiyo-e.

Katsushika Hokusai’s collection of drawings and caricatures entitled Hokusai Manga published in 1814 are worth looking at as a point of origin for modern Manga and Anime.

It all boils down to what you prefer and remember; “don’t diss the other”!

You know that one article here about anime girls? Some people in the comments are actually SJWs. And believe me, I’m NOT an SJW. Honest.