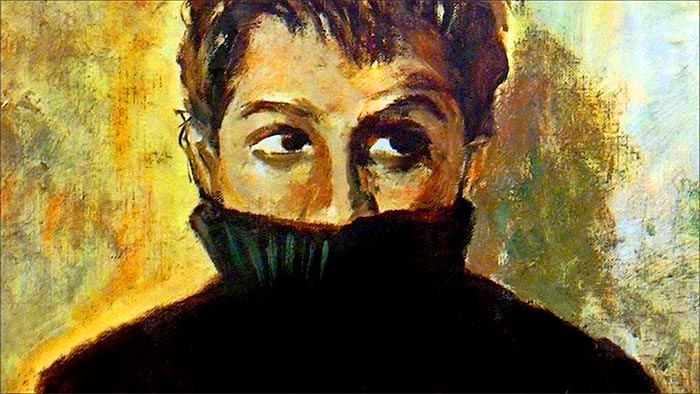

Antoine Doinel – Juvenile Spirit of the New Wave

We are often tortured by memories of youth, by situations that make us cringe, that make us look back to the past and hurt us. We wish we could have acted in a different way, still bruised by moments long gone. We relive such moments from time to time and they affect us so much that we might even break down and cry with the heaviness of pain that weighs our soul down. It’s memories from childhood that make us cry with laughter, make us sob with nostalgia, shudder with embarrassment or weigh us down with the pain inflicted upon our psyche.

Who is François Truffaut?

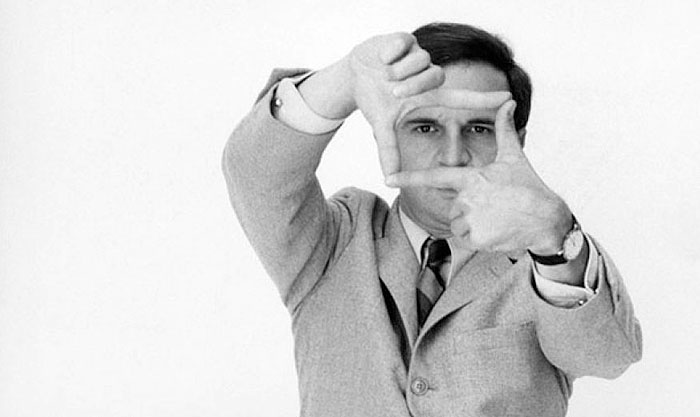

Such power is contained in Les Quatre Cents Coups, François Truffaut’s first feature film, released in 1959. It is a timeless, semiautobiographical film that transports the viewer to that moment of one’s youth when, not yet grown up, no longer a child, one starts to understand life and its injustices, but one hasn’t got the independence to fly away from the nest. François Truffaut started his career as film critic for Cahiers du cinéma, under the mentorship of André Bazin. Most of us know Truffaut as belonging to the French New Wave movement, alongside big names like Jean Luc Godard, Claude Chabrol, Agnès Varda, Alain Resnais, Jacques Rivette and others. He stands out from all these names for two reasons: the famous 1954 article, which inspects with great detail all that is wrong with the traditionalist French cinema of the age (le cinéma de papa), and the fact that he succeeded in becoming a mainstream director while holding onto his revolutionary beliefs expressed in the 1954 article. His old friend Jean Luc Godard famously accused him of having sold out, of having renounced his credo which he had so eloquently expressed during his Cahiers du cinéma career. Certainly Truffaut’s filmography is not as experimental as Godard’s, but his passion for cinema succeeded in transcending generations, cultures and languages. It captured human sensibilities and emotions with force, imagination and pathos and succeeded in cementing Truffaut’s name alongside that of his heroes: Luis Buñuel, Ingmar Bergman, Robert Bresson, Roberto Rossellini.

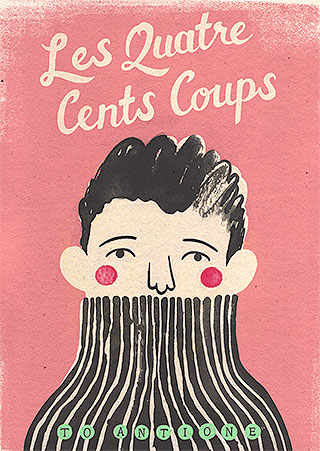

What does 400 blows mean?

The original title, Les Quatre Cents Coups, which means ‘to raise hell’ or ‘to get into mischief’, has been, unfortunately, translated ad litteram, robbing the non-French speaking world of the context before introducing us to the world of Antoine Doinel. The original title gives the audience a hint that the hero of the film is someone who tends to get into mischief, makes no excuses and won’t play the victim. However, as we will see, he will find it hard to mature, to grow out of his ‘raising hell’ phase. In Les Quatre Cents Coups and all subsequent films from the ‘Antoine Doinel’ Cycle (Antoine et Colette, Baisers Volés, Domicile Conjugal, Amour en Fuite), our hero is almost always looking out for love, life, fulfilment, almost always coming up short. Indeed, the Doinel teenage persona has haunted the real-life actor Jean-Pierre Léaud, who despite having a career outside the Doinel films, has remained associated mostly with this character he brought to life on the big screen.

Nostalgia, Paris and childhood thrills

The opening song will never cease to make me cry, regardless of how often I hear it. It encapsulates playfulness, nostalgia and, paired with a romantic view of 1950s Paris, an almost unbearable anguish tied with growing up misunderstood, unloved, dreaming of independence. The narrative follows Antoine Doinel, a 12-year-old boy who lives in a very small flat with his mother and stepfather. He’s a sensitive, fun-loving preteen who understands, to his chagrin, that he was an unwanted child. He is going to an all-boys public school, where the teachers still have the absolute power to punish and even strike pupils who misbehave. This is an all-too-real world, a time capsule of a society which saw children as adults in miniature, where “children should be seen and not heard”, where their personalities didn’t matter, where conformity was the rule of the day.

Truffaut’s Fear of Punishment

Speaking of the making of this film and what it meant for him, writer-director Francois Truffaut explained how he had sad memories of his childhood, where he was constantly afraid he would be punished for things his parents considered serious transgressions like the accidental breaking of a plate. However, in Les Quatre Cents Coups, Truffaut doesn’t portray Doinel, who becomes the director’s alter ego, as a victim. Antoine Doinel is a strong-willed boy. He is an intelligent, curious and sometimes responsible young man, who gets into trouble on occasion, but who ultimately has a good heart.

Doinel has grown up being misunderstood by the adults around him and unjustly punished. He is forced to grow up almost overnight, as he feels he cannot live according to the rules imposed on him by his demanding authority figures, those in charge of his upbringing. Jean-Pierre Léaud, the actor portraying Doinel, succeeds in transforming the character (who may have been written as a sombre, wistful preteen) into a multi-layered figure, relatable and ultimately beloved. Léaud as Doinel, under the direction of Truffaut, creates an enduring screen persona through talent, willpower and a level of roguishness that we feel is almost excusable.

Psychoanalysis in Les Quatre Cents Coups

The character of the mother is deeply flawed, with very few redeeming features. Her relationship with her son is doomed from the moment he overhears her saying to her husband (who is not the boy’s father) that they should put him in an orphanage. Antoine Doinel does not linger on this rejection. He, as most children his age, gets temporarily distracted by adventures with his best friend, skipping school and getting into trouble. His self-preservation mechanism kicks in, not allowing him to sulk or be unhappy, but take his mother’s rejection at face value and make the best out of a terrible situation.

From the psychoanalytical point of view, the relationship between Antoine and his mother is verging on oedipal, through three key scenes that illustrate the natural progression (natural at least according to Freud). Early in the film, Antoine is seen stepping into his mother’s boudoir, trying on her perfume and touching her things at the vanity table. The process is seen as if almost violating a sacred ground because Antoine is not allowed to step in his mother’s bedroom. He doesn’t have a bedroom. Instead, he is seen sleeping on a makeshift single bed in the kitchen. His status as second class citizen in the familial universe is confirmed when the mother comes home from work one night, opens the kitchen door and steps over her sleeping son to get to the main rooms of the house.

The second scene which reinforces the damaged relationship between Antoine and his mother is when he sees her kiss another man. Because he was running late for school and fearing extreme and exaggerated punishment, Antoine and his friend René skip school altogether. They run around Paris without a care in the world when they stumble across Mrs Doinel locked in an embrace with a man who isn’t Mr Doinel. She sees Antoine and is mortified. This scene can be analysed from both Antoine’s and his mother’s point of view. From Antoine’s point of view, his mother is cheating on his stepfather, but she is moreover betraying him, Antoine. The look on Antoine’s face when he discovers her could be perceived as the look of someone who has caught their lover ‘in flagrante’, not their mother. He cannot confront her, however, for he is out and about breaking the rules: skipping school. He does feel betrayed, but at the same time he is aware that his mother doesn’t love him to begin with, so perhaps the betrayal is not as hurtful as when she confesses that she would rather he were someone else’s responsibility. If we look at the scene from his mother’s point of view, we finally understand that this is a woman unhappy with her lot. She is still young, desirable and desiring, who feels stifled in a marriage of convenience, a marriage that provided her ‘bastard’ son with a name, but which ultimately doesn’t bring her any happiness. Here we must take a step back and acknowledge the difficult position of women in the 1940s and early 1950s, a time when contraception wasn’t yet readily available and when women had to pay for a moment of passion with many years of responsibility towards an unwanted offspring. Mrs Doinel has few redeeming features, but presented in the context in which she grew up and became a woman, one can almost understand her dislike and even resentment towards her son. At the same time, her backstory becomes less important when we witness firsthand the effects her indifference has on her young son. We side with Antoine, we see him as a victim of the environment he grew up in and we admire him for his strength of character and force with which he is seen battling on despite being young and unwanted.

The only moment when we see him cared for and pampered is when his mother is afraid he might divulge her infidelity to her husband. This third scene is deeply Freudian, as we see Antoine being bathed like an infant. This regression to infancy is also marked by the fact that Antoine is fully naked. Just like an infant, he is affectionately cleaned up with a towel and allowed to nap in his mother’s bed. This is used to seal the pact between mother and son, both their duplicity bringing them together, albeit for a short while. We have come full circle, back to the mother’s sacred bedroom, in which he is now allowed to enter, desecrating it and breaking the aura of mystery surrounding the mother figure. Antoine now knows that she is only human, just like him and that the reason she denies him affection has less to do with him and more to do with her. Thus, he must battle on, learn to identify his demons and live with them for the rest of his life.

Who’s asking for pity?

In the silent era there were two great comedians: Charlie Chaplin’s tramp was the one asking for the audience’s compassion, while Buster Keaton’s bum, despite being kicked around, would roll with the punches, asking nothing else but a laugh in return. Like Keaton’s screen persona, Antoine Doinel hasn’t got time for pathos and self-pity. His resilience is what sets Antoine apart. He has tried to be a victim albeit briefly (“Here lies poor Antoine Doinel, unjustly punished by Sourpuss for a pinup fallen from the sky. It will be an eye for an eye, and a tooth for a tooth!”), quickly understanding that it brings no reprieve from the pain of being a child from a broken home. He soldiers on, but the world keeps serving unexpected blows, which he must face alone. He adapts, he flirts with danger, he toys with vandalism and he lies, cheats and tries to steal away his own reprieve, but founders even deeper into being misunderstood.

How many among us have felt growing up that we were unjustly punished and thus dreamed of running away from home, just to escape the anguish of the imminent punishment looming over our heads like an executioner’s blade? Antoine Doinel, driven by that anguish, runs away from home. Hungry, cold and alone on the streets of Paris, he steals a typewriter which he then attempts to pawn off to a stranger on the street. His best friend, René, is the only one who understands him and tries to help, since he himself is another victim of neglectful parenting.

Antoine, however, gets caught with the typewriter by his stepfather. He is handed over to the police, in an example of severely cruel parenting. By handing him over to the police, later to be sent to a juvenile correction facility, they don’t relinquish their parental rights over him, nor do they admit their own failings reflected in his miseducation. They simply concede that “nothing works with this child, we have tried everything except hitting him”, suggesting that perhaps that would have been the way forward. His lies and petty crimes have caught up with him. As he is shipped away from home, he understands, perhaps too early for a young boy of 12, that he is alone in the world and that he cannot count on anyone but himself. However, he is in constant search and longing for a normal life, which he will never have. As he is locked away in, looking out into the wide world, with freedom stripped from him, he’s also outside of the normal society, looking in to a world which is ready to move on without him and which has poorly equipped him for life. He will be only prepared to run and to seek his meaning in life, without ever finding it.

Is Antoine arrogant? He could be accused of such, due to his incessant agency as well as his nonconformism, tested occasionally by all the adults in his life. He has no formal education nor is he street smart and thus he has no foundation for what can be only perceived as pseudo-arrogance, which stems from his chronic fear of rejection. He is deeply sensitive and shy, but he has developed a self-defence mechanism which can be read as disdain for all things surrounding him that displease him.

True Friendship vs Unmotherly Love

Throughout the film we see Antoine Doinel as a mischievous, playful boy who tries not to let the world’s injustices get to him. He is headstrong, which gets him into trouble and ultimately shipped off to reform school. It is here that we see the toll all his misadventures have taken upon him. Through a simple and very effective scene setup, our hearts break for Antoine as we see him deprived of his childhood and his freedom: it is vising day at the reform school and we see Antoine’s friend, René, cycling eagerly to the institution so he can see him. Antoine’s mother is also seen arriving for a visit. René is first in the line of people waiting to be let in. Alas, the guard at the entrance doesn’t allow him to visit Doinel. Doinel sees all this as he’s glued to the window, impatient to see his friend. He remains glued to the window, heartbreak visible on his face as he sees his friend denied entrance. As his mother approaches him, his eyes remain focused in the distance, waiting to get another glimpse of his old mate. The joy of seeing René is denied to him and Antoine must content himself with the presence of his cold and unloving mother. A single glimpse of freedom and a chance at normal life is encapsulated by the presence of René. This is both disheartening and hope-inducing, for it reminds us that Antoine does have a friend and that perhaps his future is not as bleak as he had originally expected. He will, thus, have to look forward to the future and nurture hope. At the same time he will create opportunities for himself and not wait to be saved by Providence.

The now iconic ending brings us hope and possibly a fresh start for Antoine Doinel, as he runs away from the reform school. His escape marks his complete rebellion against a cruel system. He may forever be misunderstood, always on the run, looking for the thrill of the sea but he’s left childhood behind and moved into adolescence. He is not a delinquent, a menace to society. He’s just a teenager. Antoine Doinel, the character of Les Quatre Cents Coups, somehow remains stuck in the psyche of the audience as the eternal teenager, leading fulfilling yet unfulfilled lives, growing old but never truly growing up.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Very nice article. I did not know anything about Les Quatre Cents Coups or Francois’ films. You did a really good job analyzing the character.

Excellent! From your first draft to this final version, you have crafted a thoughtful analysis that is truly a pleasure to read. I’ll be sending a link to this article to several friends who, like myself, appreciate French New Wave cinema. Thank you.

I am immensely grateful to you for your kind words and feedback during the redrafting stage. Thank you!

I’ve always had immense respect for Truffaut, not just because he was a great director, but also because he seemed like a really nice guy who had respect for pretty much everyone around him. Unlike say Goddard (who is admittedly a very great director in his own right) Truffaut never looked down on other directors from his position as a great and celebrated artist. He championed cinema, plain and simple, with unabated enthusiasm and love for his craft. What a man. What a loss.

I spoke with a French student of mine about Les Quatre Cents Coups, particularly about the title. She clarified for me that “quatre cent coups” is an idiom that doesn’t mean being a victim receiving 400 blows, as the literal translation suggests, but rather more like “raising hell.” The misleading translation to foreign audiences probably helps to make the character more sympathetic–his downfall a cascade of events in rapid succession, too overwhelming for an unloved youngster to arrest.

Jean-Pierre Léaud is absolutely brilliant, as a child and adult. He is one of the main reasons why 400 Blows is one of my all time favourites.

I’ve just recently rewatched Stolen Kisses and he is phenomenal there as well.

I love Jean-Pierre! I read that the moment he came in to audition everyone just knew that he was the right kid to cast!

I adore him. He is remembered by an entire generation as “Antoine Doisnel” but had many roles in the 70s, as one of Nouvelle Vague directors’ icone.

The 400 blows is a masterpiece.

So much of Les Quatre Cents Coups is as relevant and honest today as it was in 1959. What it captures so brilliantly about adolescence is that, basically, it’s awful. You’re trapped between two worlds, neither of which seem to actually trust you, or even like you. And, if you’re unfortunate enough to have parents like Antoine’s, it’s even worse. It’s such a funny, sad, breathtaking piece of cinema that never lapses into sentiment or easy resolutions.

This kid is like 13 and he knows more about Life and the Real World then like half of the people on this planet.

I cry each time I look at Jean-Pierre Léaud… The emotion in his voice, his eyes, the way he overcomes anxiety with his “joyfull” attitude, it kills me each time… He IS Childhood.

He is good, how expressive! Strangely enough at the end, he says that “… Oh me in life, I’m not sad, I am joyful!…” but on the other hand, his expression is usually sad-looking, which is used very well in the movie. He is a great actor. We reviewed that movie in college cinema classes years ago.

Gosh when I saw Les Quatre Cents Coups I wanted to just reach through the screen and hug him hard. Don’t know the last time I felt such heartbreak and empathy and love for an onscreen teenager.

Fantastic article. They should make a new version of this film. 1952 is pretty old, and old movies just had to have that annoying loud background music in every scene – which I hate – to “set” the emotion/mood.

Jean-Pierre Léaud is exceptional in this film – his spontaneity and the rebel in him, takes an amazing form in this film. My heart went out to him in the scene when his parents justify his presence. Léaud as Doinel never emotionalizes the character unless pushed to, and this is why the film is a classic!

Trivia for you. I thought Truffaut was just acting when he was in Close Encounters as Lacombe needing an interpreter for lengthy conversations. It turns out that was for real! Truffaut spoke English, but wasn’t fluent in it. He needed a translator when he directed Fahrenheit 451.

Truffaut is a genius, because he cast the perfect boy to play him as a boy in his masterpiece “400 Blows”. JPL and Truffaut are one. The best film collaboration. The Antoine Doinel films are beautiful. Truffaut is missed and so loved. His movies touch me on a personal level like no other films. He is a true auteur genius.

The 400 Blows is exactly like my young life except I didn’t steal a typewriter or plagiarise a Balzac story and I’m not French. Apart from these things, this film is exactly like my life.

I also feel like this film is basically about my younger self, I’m glad I am not the only one who had that feeling

He is searching for love and acceptance. He has poor concentration for school. He wants to be an adult, probably like his mom’s boyfriend.

Helped shaped my life even though I had my dire moments.

Congratulations on your critique. That’s the right way of doing an analysis. You’re not saying if you liked or not the movie, but giving a point of view that is based on study and knowledge. I’ve been looking for publication like this for some time, I’m glad I found it! Thank you for this.

Thank you for reading and commenting with such positive feedback. All the best!

François Truffaut is one of the most beautiful film directors the world will ever know. He was a very beautiful man with a rare understanding of life on Earth. He had a beautiful heart for genius with the determination to explain the truths in teaching: a respect for love and how to cope with (the meaning of) pain. He portrayed rare and raw truths through his films by showing to us the importance of taking into consideration millions of perspectives at once.

I dont know who the better filmmaker is but as far as the Nouvelle vague is concerned Godard is the master, his work represents the movement much better than Truffaut imo.

I respectfully disagree. I think that the beauty of the Nouvelle Vague is that it’s not embodied by a single filmmaker. It’s a movement, a wave, like you yourself said, but I think I understand why some people always pit these two against each other.

Antoine. I find his precocity almost ridiculous.

Truffaut was a master director on every level, not just the master of the new wave, but one of the greatest directors film has ever known. It is almost an insult to Truffaut to lump him in with the new wave, when his films transcend that on every level.

I agree. Although he was such an important part of the New Wave, his work matured into so much more, especially with such different films like La Nuit Americaine and Le Dernier Metro.

Watched 400 Blows last night after reading your piece, it was an amazing masterpiece. Endless thank you’s.

Truffaut said he owes everything to the 1953 American film Little Fugitive which influenced him and started French New Wave.

I love how your article turned out! And I’ve (finally) seen Les Quatre Cents Coups, so it makes your analysis even more enjoyable! Thank you !

Very kind. Thank you! Hope you enjoyed the film x

truffaut is one of my favorite filmmakers ever as i not only enjoy his work but also the fact that this is a man that loved cinema.

François Truffaut didn’t believe in God so the cinema became his religion. It was his way of filling up the existential vacuum within him.

Completely made up story.

ive just finished watching the 400 Blows and i couldn’t even begin to fathom what i was supposed to even feel, it is thanks to film essayers like you and many others that help enlighten newcomers like i.

The 400 Blows is one of my favorite films ever.

Such a great analysis of the psyche of one of the most iconic characters in film history!

A nice essay. I like the perspective of referring to the silent picture era.