The Black Death and Sensationalized Medieval History

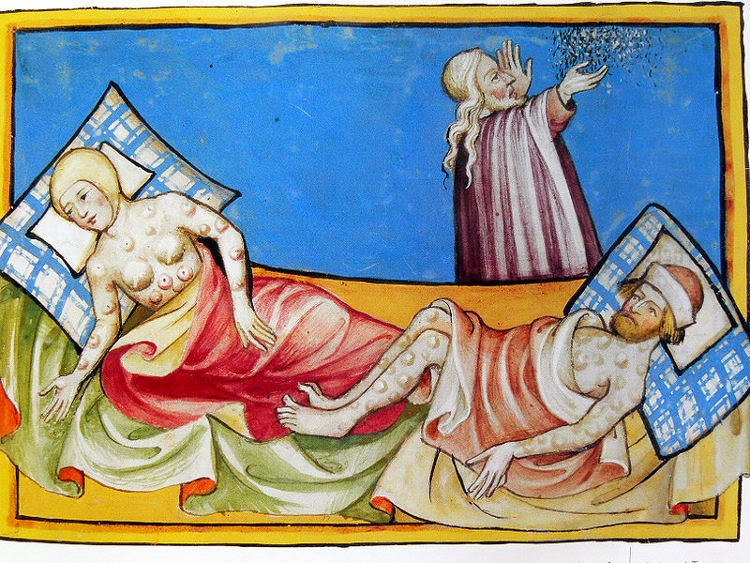

The Black Death, particularly the first outbreak of the late 1340s, has long fascinated historians, medical researchers, and the morbidly curious. Be it the economic collapse, the oozing pustules, the unrestrained panic, or the violent scapegoating of the Jews, there’s a little something for everyone in the study of the 1340’s infamous medical disaster. Resources on the Black Death range from dry and purely scientific to outright pulp, but the most widely consumed tend to be somewhere in the middle of the spectrum. They must be grisly and dramatic enough to engage the casual audience, yet grave and factual enough to keep the attention of the scholar; anyone who falls somewhere in between may be doubly piqued or insulted, depending on the tone and the consumers’ preferences.

For the sake of exploring the differences named above, I have selected two secondary sources on the plague of the 1340s: The Black Death, a 1969 text produced by Philip Ziegler (a biographer and historian but, by his own admission, not a medievalist) and Medieval Apocalypse: The Black Death, a TV documentary aired by the BBC in 2013. Both are aimed primarily towards interested laymen rather than well-versed historians. These resources, while each moderately useful in their own rights, do not provide concise reports of medieval medical history as much as they represent their home decades’ approach to grizzly history and a culture which is popularly panned as backwards and infantile. This in itself provides a fascinating timeline of how medieval history has been perceived over time and how it has been popularized.

Aside from the obvious difference in medium and decade, the greatest differences between the two sample texts at hand are tone and level of scholarship. The Black Death is not entirely dry, nor is Medieval Apocalypse entirely without substance, but the former is far more concerned with comprehensive documentation, where the latter focuses upon entertainment. This is not inherently problematic for a documentary to do; however, in the case of Medieval Apocalypse, pivotal information is not just glossed over or left out, but in at least one case it is blatantly misrepresented. “Even today, modern medicine can’t explain what the Black Plague was” (BBC), the grim narrator says, more than a full half hour into the production. How scary! Zeigler, meanwhile, devotes an entire section of his book to the biological and historical foundation of the European Black Death; it is entitled “Origins and Nature,” and it is the first chapter in the book. In it, he credits a perfect storm of three separate plagues (bubonic, pneumonic, and septicemic) which, while unrelated, were perpetuated by the same dire conditions: overpopulation, famine, poor hygiene, and hard labor. This was the presiding belief of his day, and it is, in fact, different from the 21st Century amendment thereof by a hair. Today, historians and medical researchers believe that these three plagues were all caused by one root bacterium: Yersinia pestis (Benedictow), a minor but key detail which escaped the medievalists of the 20th Century.

The BBC’s documentary, meanwhile, does not have the excuse of widely circulated misinformation, as the Yesinia pestis revelation came to us in the mid-aughts, almost ten years prior to Medieval Apocalypse’s airdate. Furthermore, there is no mention in the documentary of the biological attack from the Tartan army nor the transmission of plague from fleas and rats. The key roles played by infected sailors and Italian trade routes receive a brief mention, but it compares very poorly to Ziegler’s research. Any discussion of such key information is left out of the film in order to build an air of mystery and terror, as if to say, “The plague caught medieval Europe unawares; the same could happen to you at home any moment.” This blatant misrepresentation of facts is a cheap ploy to frighten the audience rather than inform them. This is downright puzzling by the end of the film because, by that point, the most grisly and stomach-turning behaviors of the panicking medieval citizenry has also been left out, aside from a brief reference to the use of human feces in medical treatments. Where Ziegler is exhaustive, the BBC skimps on information.

Ziegler’s greatest flaw as a novice medievalist is his utter lack of cultural relativism. He frequently offers personal inference and commentary which may strike the modern reader as overly judgmental, dismissive, or blindly intuitive; this is most obvious in his great pity for the supposedly wrongheaded and superstitious citizens of medieval Europe, referring to their behavior as “primitive and violent” (58), stating that “Medieval man skated on the thinnest possible ice of verified knowledge with beneath him unplumbed and altogether terrifying depths of ignorance and superstition. Let the ice break and with it was lost all grasp on reality and all capacity for objective, logical analysis” (29). Though he is frequently informative and entertaining, a misplaced air of superiority is Ziegler’s cardinal sin. This level of flippancy is compounded by his recurrent praise for doctors of antiquity, speaking as though the genius and influence of Bede, Hippocrates, and Galen was a brilliant light doused by a characteristically medieval miasma of stupidity, rather than the innovative work of men constrained by their own times, just the same as anyone else. Thus, his failure to contextualize his own time’s ignorance and irrational biases is doubly ironic. He even goes so far as to bemoan the absence of Hippocrates from 1340s Europe, as he would surely lead the misguided medieval lambs from the pestilent slaughterhouse. “Given the state of medical learning no great leap forward was possible but if Hippocrates had been alive he would at least have discarded a lot of dead wood of proven uselessness and made some sensible and valuable deductions about the conditions in which the epidemic seemed to thrive and the best means of removing them” (57). Ziegler’s disrespect for medieval conventions, medicine, and general populace is blatant, although he has, for whatever reason, taken a liking to several historical figures and chooses to frame them as noble and wise, whether the records indicate such attributes or not.

There is no doubt that [Pope Clement VI] was preoccupied by the horrors of the plague and genuinely disturbed and distressed for his people. Though by no means celebrated as an ascetic he was good-hearted and honorable, anxious to do what was best for his flock… Not unreasonably, Pope Clement VI calculated that nothing would be gained by his death and that, indeed, it was his duty to his people to cherish them as long as possible. He therefore made it his business to stay alive… He retreated to his chamber, saw nobody, and spent all day and night sheltering between two enormous fires (49).

Ziegler remarks upon the Pope’s actions as if he were his defense attorney, rationalizing his attempts at self-protection (which may strike the unled reader as selfish or pigeon-hearted) by couching them as active service to the suffering underclass.

This is in direct contrast to the BBC’s representation of a hard-faced, impassive Pope Clement VI, who lay in cloistered wait of reprieve from the plague betwixt his aforementioned fireplaces. He is neither praised for presupposed bravery nor is he reviled for possible cowardice; he simply is, and no erroneous conjecture addressing his intentions, attitude, or moral character is suggested. In this case, the comparatively histrionic Medieval Apocalypse outperforms Zeigler’s pivotal academic text. However, this distinction is not always so stark. Both sources show great respect for Giovanni Boccaccio, the Black Death’s most notable first-hand witness. Even when taking potshots at medieval census takers for their lack of “sensibility” (37), Ziegler forgives Boccaccio’s prosaic approach to documentation and his implausible statistics, thus extracting valuable information from his Decameron. “In its picturesque detail, therefore, one must accept Boccaccio’s account as accurate and authentic” (36). Ziegler does a much greater service to Boccaccio and The Decameron than the BBC, which paraphrases his recordings once, where Ziegler provides complete translated excerpts repeatedly throughout his chapter on Italy.

The exploitation of horror and empathy is rife throughout Medieval Apocalypse, both for better and for worse. Ziegler has already been established as particularly dismissive of medieval medicine and ideals in general, much as he also employs a dry tone in his prose. However, his presentation is not so extreme as to contradict the BBC’s approach. He too, seems to enjoy the occasional gruesome turn of phrase. For example: “Even in the materialistic and, at a certain level, sophisticated nineteen-sixties the apocalyptic vision of a world about to incur destruction through its own wickedness and folly is my no means lost. Man-made devices may have been substituted for the pestilential hammer” (23). This is where he is at his most empathetic to medieval Europeans on the whole, wherein he explicitly places the 1960s into the 1340s’ shoes, so to speak.

This analogy between the medieval fear of self-inflicted divine cataclysm and the atomic agers’ nuclear dread is reminiscent of the connection Medieval Apocalypse draws between 2013 and pre-plague Europe. From timestamps 2:51-3:05, B-roll of modern European citizens roaming through an outdoor marketplace are spliced with narration praising the cosmopolitan nature of mid-1300s medieval society: “In the mid-14th Century, Europe was not the dark continent so often lampooned by history. It was well populated, sophisticated, mobile, and devout.” Though vaguer than the parallel between the fear of God and nuclear war, likening ancient prosperity before an inevitable collapse to the early 21st Century mode of society creates a viscerally anxious tone. Is this film alluding to life before and after the global economic collapse, or is it implying that the worst yet to come? This brief flash is open ended enough to allow the viewer, whatever their politics, to make an instant emotional connection with the subject material, and it comes early enough in the film that this empathy tints the viewing experience that follows. This sensation is vindicated by the optimistic afterword, again played over stock footage of modern people, complete with the angelic orchestration of strings, piano, and a choir: “One of the healthiest conclusions is to remind ourselves that Europe survived the Black Death; it survived recurring outbreaks for 300 years of plague, and I think that’s a very good conclusion to get out of this. It’s the resilience of the human spirit in the face of this appalling adversity.” Medieval Apocalypse is more concerned with emotions than it is with actual documentation. At its best, it provides empathetic, relativizing imagery like the previous example.

At its cheapest, Medieval Apocalypse flashes images of maggot-filled human skulls on screen in a petty attempt to horrify its viewership when it might have used that space to educate them. At its absolute worst, as stated earlier, well established historical theories are completely discarded for the sake of dramatic effect. Ziegler may present a distinctly antiquated perspective on medieval society and intellect, but he is at the very least concerned with imparting thoroughly detailed research. Medieval Apocalypse is, in many ways, less a documentary than it is a cathartic bio-pic which provides historical “cliffnotes” and the occasional ghastly image in order to retain viewers.

In spite of any historical accuracy, respect for medieval culture, or any combination of these two retrospective virtues, documentation of the Black Death is sensationalized by both samples provided here, in their own ways. While Ziegler’s prose is stuffy and judgmental, much of the information he provides is still useful and detailed. The televised historical documentary, meanwhile, breezes over key information for the sake of imparting an element of terror to the production. This is an attempt to hold the attention of a morbidly curious viewership, rather than an in-depth appreciation of history. The other side of this particular coin is that Ziegler’s opinion of medieval civilization is so low that it skews much of the information he provides; in other cases, he projects personalities onto historical figures in such a heavy-handed manner that many of the conclusions he draws become suspect. Medieval Apocalypse and its approach to infotainment (emphasis on the “tainment”), however, lends a sense of empathetic respect to medieval culture that Ziegler obviously does not. A comparison between today’s Europe and the plague-bitten Europe of yore is distinctly drawn throughout, which is both the heart of the documentary’s focus on cinematic horror and its greatest success over Ziegler. Neither approach to medievalism is especially “correct,” but neither is devoid of value either.

The factual inaccuracies one might find in purportedly non-fictional material such as the medial texts described here are, to say the least, disquieting. The search for authoritative knowledge becomes more of an ouroboros than a linear path; one cannot vet useful source material properly without first developing a knowledge base in the focal subject, but that knowledge base cannot be developed without an uninformed foray into a minefield of suspect sources. This problem is evident, not only in medieval scholarship, but in the news, in public school textbooks, and on social media. In some cases, fiction can be separated from the facts with relative ease, but others remain horrifically vague.

At the end of the day, The Black Death and Medieval Apocalypse are intrinsically flawed resources. Both of these pieces are often misleading and should not be taken on faith. However, each provides fascinating commentary on the 14th Century plague outbreak and may serve as a jumping off point to the curious scholar. When compared side-by-side, Ziegler’s manifesto and Medieval Apocalypse are much more adept at representing the zeitgeist of their own time periods than that of the 1300s; when compared, they outline the evolution of historical horror, medievalist attitudes, and the ways in which scholastic laymen are addressed.

Works Cited

Benedictow, Ole J. “The Black Death: The Greatest Catastrophe Ever.” History Today, Vol. 55. Issue 3, 2005. historytoday.com/ole-j-benedictow/black-death-greatest-catastrophe-ever.

Medieval Apocalypse: The Black Death. BBC, 2013. youtube.com/watch?v=ffaoF0xkUTo.

Zeigler, Philip. The Black Death. 4th Ed. The History Press, 2010. Print.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

I think we take for granted things like modern medicine and the general knowledge of how bacteria works. Imagine going to the doctor today and having your wounds treated by having feces rubbed into them.

I am super interested in the Middle Ages or the Plague so this article was a treat. Cheers!

Recently read the 1969 text. About the first 100 pages were very interesting when it was talking about where it came from and why it might have spread so dramatically,and then it kind of fell off with a lot of statistics with numbers of deaths, etc.

Slightly dated but a very good reference book none the less.

I would recommend this book to anyone who doesn’t mind a dry history text with knowledge that you will only be able to drop at the most random times.

It is the most comprehensive book I’ve read on the plague, and I’ve read a lot.

The text is very dry and the subject matter relates to ghastly death on a massive scale, but I found it all very interesting. Many others probably would not.

The last chapter in which he imagines the impact on a small Hampshire village is particularly good.

Great analysis. I hope this piece will work as some form of foundation for everything subsequently written about the black death in the digital media.

An excellent article and a good read as well. Thanks.

fantastic analysis and great historical overview. This was a pleasure to read!

It is normal in the study of history to address how the times one lives in can effect how an historical period is studied. Civil War studies have gone through a tremendous transformation since the period when many white Southerners wrote about that war.

If you know me, you know I’m obsessed with The Plague. This article will be shared with friends and foes!

Ziegler makes a great point about how historical sources can place events months apart.

Lovely piece. To people who are interested, try “The Black Death: Natural and Human Disater in Medieval Europe”.

I can’t imagine living through something that claimed the lives of 1/4 to 1/3 of my neighbors.

Can you imagine if the black death didn’t happen? how different the makeup of the world would be, i feel like almost all people right now would be different people because different ancestors and relationships most likely would have happened.

Interesting but disgusting. Thank you for sharing.

Every documentary about medieval times is basically a documentary about ignorance.

Interesting how when they thought their god had abandoned, them these previously pious people turned to debauchery. Yet it is supposed to be the atheists who are morally bankrupt.

Brilliant and engaging article!

Gruesome to read about the black death. I love it though!

Fascinating topic!

I expected this to be overly depressing account of a terrible human experience but it wasn’t. Thanks for sharing.

In that documentary, I think it’s pretty cool how the actors made it look like the people themselves were interviewed.

I used to wish to go back to medieval time to see what it was like…After learning of the lack of sanitation…..poop in the streets, dead animal parts in the streets, disease etc…..No thanks

A while ago I was thinking and realized my ancestors had to survive a lot of crap for me to exist. Thanks fam, for not getting killed by the black death, burned at the stake, poisoned, drowned, and all kinds of stuff.

Such an interesting topic! Love it.

A great read and a really good analysis of the core text. Nice work. Plus always an interesting topic!

Having recently finished 1666: Plague, War and Hellfire by Rebecca Rideal, which I thought was fascinating and very well written, I was keen to learn more. Reading this article on the same topic was a fascinating look at two potentially useful resources offering different perspectives. Thanks for the great comparison and insight.