…But is it ‘Art’?

There has been a long-standing debate whether certain practices or pieces of work should or shouldn’t be called art. First of all, one needs to describe what is understood by the term art in order to set the outlines of such a discussion. This can be done by an acknowledgement of the various contexts and histories that go along with certain readings of the word. Furthermore, looking at the essence and purpose of the sphere of art, there are major differences between the so-called Western (European and North American) and Eastern (Asian) points of view, to that of certain tribal communities, for example. Each reading goes along with its concrete context and specific receptions within this context. Nevertheless, what is most interesting for audiences, critics and artists alike in the current day and age, is the quesiton ‘what can qualify as art and why?’.

Talking about the general idea of art, however, there isn’t a universal, commonly agreed description of what it is, since it is always evolving and adapting. Until now people have regarded art as a diverse range of human activity, and its resulting products, that involve creative manifestations generally expressive of technical proficiency, talent, beauty and emotional power, or conceptual ideas. This is, therefore, the essence of what art should be – something that moves the spectator, the receiver, the reader, something that makes them think and feel. The art world, on the other hand, is a much more complex notion. It is a field burdened with the task of conceptualising this essence and creating a somewhat coherent infrastructure for its existence and circulation. In other words, anything can be regarded as art, as long as it reasonably justifies its place in the art world. Often the two concepts get mixed up, because after all, there can be no art without the art world and vice versa. The questions we ask here, however, are how can we fairly evaluate a piece of work as art or not? Is it enough to look at a given piece only through the prism of talent and proficiency, or is there something more beneath the surface, something that can be truly inspiring and thought-provoking?

In order to answer some of these questions, we need to look back at certain historical developments and ideas, and how they have influenced our perception of contemporary art.

The age-old question: Can there really be “art for art’s sake”?

“Art for the sake of art” is a slogan dating back to the 19th century, when people from the intellectual circles of Paris started using it to describe the idea that art is, and should be, separated from all utilitarian functions and independent from any social values. In other words, according to this belief, one should focus solely on the skill and craftsmanship invested in the making of a particular piece of art or the virtuosity and skill with which it is executed, without taking into consideration the deeper meaning or the wider impact of the piece. However, the idea that works of art can exist in a vacuum, unaffected by the circumstances of the artist or untouched by the context in which they were created has led to the establishment of a dominant view of the art world, one which is substantially harmful to some more unorthodox artistic practices, which do not rely solely on talent or proficiency. Such marginal, unconventional practices include some forms of performance art, installation, experimental theatre, body art and other mediums, in the past referred to as the equivocal low art. These practices do not always take into account the skill of the artist because it is irrelevant. What is important is the message and/or the effects which are accumulated through the piece. In other words, it is the bigger context, the hidden deep meaning or the audience’s personal interpretations that matter in this case.

Some critics and audiences view modern art pieces, ones which are radical, unconventional, or simply conceptual, as non-art, because their effects and meaning are not delivered in a traditional manner. That is to say, the message is not straightforward and readily available to the viewer. Often such work is difficult to comprehend or accept because one needs to engage with sensitive, intimate and therefore complex questions. In such cases, critics and audiences might argue that a certain execution and final product cannot be referred to as a piece of art, due to its irregularity, alleged lack of meaning, or even – because of its ‘apparent’ simplicity.

One example of such unusual artwork is My Bed by the English artist Tracey Emin.

The installation was exhibited at the Tate Gallery in London in 1999 and consisted of the artist’s unmade bed with personal everyday objects, such as underwear, a pair of slippers, tissues, condoms, bottles of vodka and other detritus, in a scattered state around it. The work was created as a powerful image, the aftermath of a four-day long self-imposed starvation, consuming nothing but alcohol, after a mental breakdown. Ermin explains that this was a depressive state, a semi-delirium, caused by personal troubles and relationship difficulties. Despite some critics’ ardent disapproval, the root and inspiration for the piece represent an honest, outrageous, yet unapologetic, personal statement. The work gained vast media attention with some reviewers arguing that anyone could present an unmade bed with a pile of junk around it and proclaim it as art. However, Emin’s response is that, first of all, no one else has in fact created and exhibited such work, thus making her idea, to take the bed out of her room and place it in a gallery context, unique. The underlying effects of this action, therefore, stem from the fact that as a conceptual piece My Bed is no longer simply a woman’s messy house furniture, but an idiosyncratic archive of personal experiences, pointing towards mental health awareness issues and engaging with institutional critique – asking who, what and why has the right to inhabit an art space? Emin chose to expose all the chaos, decay and disorder that comes with depression in the most abrupt possible way – without concealing anything, without rearrangement, without artifice.

This goes to show that nowadays the art world is becoming evermore complex, with artists, audiences and institutions trying to navigate sensitive topics and multilayered issues, while simultaneously engaging with and producing meaningful, powerful art. Questions of social, political, cultural, economic and even personal essence are all entangled in the readings and receptions of a piece of work. This is making the work of critics and curators all the more difficult. Not to mention the obscure practices which merge and blur the boundaries between art and life, such as Breyer-P-Orridge’s decision of transforming their body and quotidian life into a curated art project, or Anne Bean’s work with various personae outside traditional art spaces and into her everyday life. How do you categorise something as being art or not? Is the context in which it was created/showed/performed all that matters? Or is it the reception of the piece that is most valuable? Even then, how should one decide which elements are important to the piece and which are irrelevant?

Subjective vs. Objective

Discussions around these questions have been circulating in the art world for decades, ever since the first Futurist Manifesto in 1909 by Filippo Tommaso Marinetti. It is believed to be one of the first starting points to send the idea of art into a whole new direction. This is when artists started experimenting more and more, yearning to cross boundaries, escape limits, and go beyond the traditional modes of expression. As one of the many avant-garde movements that followed, Futurism was mainly concerned with innovation – new ideas and beliefs, which centred around a rebellion against beauty and good taste, renouncing all the themes and subjects of traditional art.

Artists were not interested in the approval or disapproval of critics and audiences. Rather, they wanted to create art inspired not so much by subjective experiences and emotions, but by objective realities, like the advancements of the modern world, in the face of new technology, science and machines.

Later, in his famous book The death of the Author (1967), literary critic Roland Barthes lays out another prominent idea – that the meaning and therefore significance of a text cannot be determined by the author’s initial intention, rather it is up to the readers’ interpretation to bestow it with essence. According to this theory, one cannot rely on the biography or identity of the creator to distill a definitive meaning and a certain definition to the creation. This allows for a much broader understanding of a piece of art, since every individual reading would potentially carry multiple backgrounds and connotations, varying degrees of comprehension and would therefore pay attention to diverse aspects in different ways. This is an interesting point of view with regards to the art world as a whole. Particularly with the question whether a piece of art can be isolated as a stand-alone phenomenon (with a preliminary message and a foreseen effect), always linked to some sort of a universal criteria, or, each artwork is dependable on a multitude of, sometimes uncontrollable, elements (the audience’s reaction; the sociopolitical context; cultural and historical background; economic situation, etc.).

This is not to say that the artist’s identity and circumstances are of little or no significance. Sometimes, especially in autobiographic performances, for example, the identity of the artist is the essence of the work. Nevertheless, it is always up to the uncontrollable force in the face of the audience’s receptions, to make sense of it and therefore to give meaning to it. It turns out, it is difficult to judge a piece of art separated from all these elements, regardless if we realise it or not. The prism through which we look at and analyse a certain artwork is always informed by our preconceptions, knowledge and experiences. This is the hidden power of contemporary conceptual art – two people looking at the same thing can have two completely distinct thoughts and experience, and therefore understand it in a different way.

One viewer might be more concerned with the aesthetic qualities of a piece, another with its connotations and emotional effects, and so on. Therefore, the main issues regarding what qualifies as art, circle around questions of aesthetic values, utility values and truth values – all of which do not have a unequivocal standard. Does this mean that it is irrelevant and meaningless for critics to try and explain artworks? Short answer would be – no, because the very endeavour of putting a frame around the experience is what makes it part of the art world. Moreover, there is a long history of art, which informs and problematises current approaches to the sphere, making it all the more interesting and challenging.

High Art vs. Low Art

To trace the root of these debates, we need to go further back, to the 18th century, when the distinction between forms of art in the categories of high and low is believed to have taken shape. Fine art in the forms of painting, sculpture, theatre and music were held in high regard, as attention was focused on the talent of the artist and the mastership with which the work was executed – the details and forms, all aligned with the general criteria of critics in the sphere. On the other hand, low art was considered less masterful, something to be enjoyed not by a selected few with refined taste, but by the masses, a cheap form of entertainment. This concept, however, developed into something more than just a categorisation of the different branches of the art world. It imposed an almost universal claim of what is and what isn’t worthy of critical attention. In other words, this distinction set a tone for what was to be considered art at all. Nowadays, however, there is substantial shift in this understanding because certain forms and mediums, which would be considered low, are paving their way to a more renowned spotlight, affirming their significance and therefore value as pieces of art. Performance art practices, for example, started off as marginal activities, which nevertheless proved to be a radical catalyst for social and cultural change.

Performance Art

In the beginning of the 20th century, cultural and socopolitical atmospheres in Europe shifted. The access to both higher and lower art forms became more widespread, making the lines between them blurred and somewhat irrelevant. Artists were focusing more on the message and impact of their work rather than their skill and perfect execution.

Despite the effort of some regimes to dictate the taste of the people (such as Socialist Realism in Eastern Europe), unconventional performances flourished. But when artists were not conforming to the state regulations and were creating unique and difficult pieces, their work was deemed as perverted, as non-art, something to be condemned and forgotten. Nevertheless, artists found numerous ways to continue to create innovative, imaginative, challenging, disruptive works which later proved to be a vital development for the art world as a whole.

As time progressed, so did the approaches to art and art-making. Nowadays, the sphere encompasses a vast number of modes and strands which continue to grow. For example, NFTs and digital art are yet to be analysed and discussed in the context of contemporary culture, as they have a great impact not only in the sphere of art, but also in the realm of social media, AI creative practices, and even economy and finance.

So… is it art?

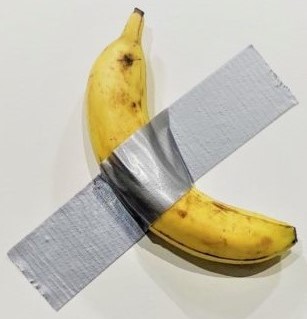

To close off the current reflections, let us bring this classic into the discussion – a banana, duct-taped to a wall. Does it qualify as art? Short answer – it does if you want it to. As mentioned before, art is primarily subjective. The work, titled Comedian, was conceived in 2019 by the italian artist Maurizio Cattelan and was displayed at Galerie Perrotin’s booth at Art Basel Miami Beach. It was sold for US$120,000.

Despite the mass outrage regarding the price, there is a lot of underlying meaning linked to the piece whatsoever. The majority of the media coverage focused on the simplicity of the work, deeming the sum of money as inexplicably high. What the buyers received, however, was not the banana itself (which would rot eventually, thus ruining the work), but the idea for the work. As conceptual art, it consists of a certificate of authenticity with detailed diagrams and instructions for its proper display. The uniqueness of the piece is in its sarcastic nature and the references it makes. The title Comedian can be seen as a tongue-in-cheek vaudeville reference to slipping on a peel. Cattalan is also known to use Duchampian strategies in his work in order to highlight the ridiculousness of some institutions and the absurdity of some modern tendencies. In an interview, Bill Powers, Half Gallery owner and art dealer, says:

”The genius of Cattelan’s banana is that it draws out the mainstream media’s suspicion that all contemporary art is a type of emperor’s new clothes foisted on rich people. Was it Warhol who said, ‘Art is whatever you can get away with’? Case in point.”

This is a bright example of how a simple, yet clever idea can bring the whole art world and social media on their toes. It was reported that insane crowds formed in front of the gallery, security got involved, and official queues were set up. This led to the installation being removed because it posed a serious health and safety risk, as well as an access issue. However, it still remains as a prominent moment in art history, whether one sees it as art or not per se.

Art is a magical thing. Something that belongs to each and everyone, regardless of their position or origin. One does not need to be an artist, art critic or to study art history in order to appreciate and understand it in their own way. Even with complex contemporary performances or bizarre conceptual pieces – frustration, anger or confusion are all purposeful emotional effects which can lead to a thought-provoking experience.

So, next time you wonder whether a certain piece is in fact an artwork or not, ask yourself this – does it make you think and feel in a certain way? If yes, then how and why? The very act of asking youself these questions already means that the piece has done (most of) its job.

Bibliography

Elise Taylor, The $120,000 Art Basel Banana, Explained <https://www.vogue.com/article/the-120000-art-basel-banana-explained-maurizio-cattelan>

Genesis P-Orridge, Nonbinary: A Memoir (Abrams Press), 2021

Rob la Frenais, Anne Bean: Self Etc. (Intellect Ltd, London), 2019

RoseLee Goldberg, Performance Art: From Futurism to the Present, (Thames and Hudson, London) 2011

The Routledge Companion to Aesthetics, ed. by Berys Gaut, Berys Gaut, Dominic Lopes, ”High Art Versus Low Art”, John A. Fisher, (Routledge, London), 2000

Tracey Emin on ‘My Bed’ | TateShots <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uv04ewpiqSc&ab_channel=Tate> [02 April, 2015]

What do you think? Leave a comment.

I think it was David Hickey who said that art is a negotiation around a subjectivity – And I agree completely.

If Ai’s smashing of a Han dynasty urn is a satire of anything, I can’t help thinking it’s a satire of our reverence for a given object solely because it’s old, regardless of whether it’s otherwise valuable as art, for research or for actual use.

If Ai was able to buy that set of urns inexpensively enough to use as raw material, there are presumably enough of them around already to teach archaeologists and historians whatever there is to be learned from them. At their age, those urns are unlikely to be as useful for storage as more recently-made articles of similar shape and size.

That leaves aesthetics. Certainly those urns have an attractive shape, though that shape is doubtless easily replicated. That being the case, as long as they aren’t the last of their kind, are those plain dun-colored urns really so important or beautiful just because they’re 2,000 years old? Honestly, to me they look a lot more beautiful in the bright colors Ai painted on them.

Fact is, that only through acts of notoriety would anyone of you all ever noticed. Warhol understood-art, as it is assimilated a ad ‘recognized’ – is strictly via mediation. The art of WeWei is is ‘known’ through mediation. You only know of him because of media friendly gestures -provocations if you will.

Have any of you actually been to china? You have a right to judge the artist in his own cultural context.

I wish the rich people who run the art world would get tired of kindergarten-level paintings and move on to some other shtick.

I feel like sometimes people try too hard to find meaning in things that don’t have any. But I guess if it gets people talking and thinking, maybe that’s the whole point?

This article makes a good point about how art is meant to evoke emotion, even if that emotion is confusion or anger.

Art is about creativity, and if that means a banana on a wall, then why not?

I think it’s pretty cool how something so simple can spark such big conversations about what art really is.

I’m torn on this. On one hand, it’s hard to take it seriously, but on the other, I respect that it’s challenging the norms of what we usually call art.

I agree. Art is supposed to evoke emotion, right? Maybe that artist was aiming for frustration.

I’ve always thought art is just a way to express what words can’t. It’s something deeply personal, like a window into someone’s soul. Even if I don’t “get” every piece, I feel like it’s still valuable because it’s someone’s unique perspective on the world.

Yes and no.

Why should there be an explanation for art? why does art have to have a meaning? or rather, why should it have a general meaning. why can’t it be left for interpretation to individuals, rather than a few who will decide creative outcomes for the rest.

Art is the physical and emotional response to the nature of things.

The problem is left of who is an artist?

i believe it is those people who have made a significant contribution to the development of art (and who thereby are eventually recognised as historically important figures). i don’t believe people who make a living selling decorative abstractions, people who produce work looking like it was made in 1840, people who buy a box of expensive watercolours, Hyde Park railers, fresh-out-of-college fifth-rate Duchamp copyists with a CV and a business plan, hairdressers or flower-arrangers are ‘artists’. these can be forms of creativity but not of the same degree of originality and importance, or purpose, as Picasso, Duchamp, Pollock etc. whose work can be safely and reliably called Art.

the work of historically important artists is not only a profound and coherent expression of the complexities of their age but also usually a wholly original manifestation of what is possible within the medium of art – pushing the boundaries of what can be done with paint, for example.

What about contextualization? Isn’t it a bit authoritarian to say ‘What art is’, as if there were such things as absolutes when we come to cultural phaenomena?

That’s exactly how this article starts – an acknowledgement of the importance of contextualisation 🙂

I believe art to be anything which can primarily stand as a vessel for thought.

A great piece of art needn’t be typically beautiful, representative or well thought out.

Narrowing it down to painting for example, a great painting needs only to display the pattern of decisions made throughout it’s creation, these decisions will be determined by the artists temperament and will therefore be representative of the artist and all he or she has to say.

Painting is the medium of thought, thought can be actualized in painting and will therefore stand as the result of the artists subconscious mind and it is there to encourage the viewer to do the same, to think and think and think.

Ai Weiwei is a complete and utter no-talent, a moral idiot, and a worthless poseur who wants to seem provocative, but doesn’t really know how, so he degrades and travesties the work of skilled artisans — anonymous laborers who surely do not need to be made “ironic” to be appreciated.

It’s a simple case of ownership.

Those trying to seek an equivalence in the Mona Lisa and a pot that, despite it’s age, is neither significant or valuable are barking up the wrong tree.

Of course, irony in art/music/film, rather than being incisive, or deconstructive, now merely affirms the status quo of generalised scepticism to spiritualism or progressive naratives and is thus not particulalrly shocking or informative any more.

Most contemporary artists seem to lack even any belief in the purpose of what they are doing, other than a shot at living a pseudo-glamarous lifestyle and doing something “they love.”

At least modernism generally had something to say for itself and those webs of meanings which interlinked with other spheres (such as politics) were certainly no guarantees of good art, but they formed a climate of meaning in which art could exist and feed off something other than itself. The repurcussions of this could be measured in aesthetic gains even if the politics fell flat.

‘Tarkovsky’ for instance, foremost religious obscurantist, but driven by a deep sense of meaning which fed into new artistic and high-modernist output.

No belief = no art

Art of an artist is always a commentary on specific subject usually revealed in artists specific to particular collection of works mission statement and all that affecting the author, world artist lives in, political, social etc climate. In this it is valuable whether I personally like it or not. It creates a wider view of the world current to the time of creation of the artwork.

I think we can lay the need to explain ones “art” at the feet of “conceptual art” when I was in art school in the 70’s it seemed that if you could write a explaination then anything no matter how rediculous became art ie. stapling kleenex to the wall or writing a dirty word over and over, it left those of us who loved a more traditional approach wondering if there was a place for beauty left, thank god there is.

Sometimes just creating / painting for the sheer joy of it or for the feel of the paint and interplay of color is all the peice is about other time there is a subject it can be photo realist or abstracted by the creator portraial of the play of light, shadow and colour over the surface of the object.

I remember an early abstract I played with one summer and tagged on the back as “Dance of Sea Demons” later a friend who was in the navy saw it haning on my wall and commented “looks like a ship going astern in Burmuda”

Unless the subject is obvious I refrain from naming or explaining as I like my friends explaination best anyway LOL I think all an artist need put on the tag is the medium, ssustrate and ddate painted.

Sorry I’m rambling. Great article.

Can you tell that it is art in the first place? Lots of art, or “stuff” poporting to be art, is in fact not art at all. Simply to assume “art”-ness because of the context in which you see it, or because someone who “knows” has told you, or because someone who calls themselves an “artist” has said so, is a mistake.

I like your term ‘art-ness’! It turns the whole converstion in an entirely new direction – is ‘art’ an adjective, as you propose, something to be possessed by a concrete work, or is it a noun, or even a verb as it almost seems to have a life of its own?

Ai Weiwei owned the Han Dynasty urn he smashed. It was his to do with it as he pleased. i have never liked or approved of that “statement.” But i admire Ai Weiwei for his activism and artwork. A very hard to come by interview of him was fascinating, a few years ago.

I lean towards the idea that art is the expression of the noumenal.

You can’t make something art just by saying it’s art.

What is art?

Baby don’t hurt me.

Don’t hurt me.

No more.

Should the first question be ‘What is art?’ or should it be ‘What is art for?’

Just wondering – I haven’t got a bleedin’ clue and I’ve been trying to figure it out for thirty odd years.

I honestly can’t believe a banana taped to a wall can be considered art. But then again, maybe that’s the point – it challenges what we think art should be. It still blows my mind someone paid that much for it though! Guess it proves art really is subjective.

I remember when that banana went viral! It was hilarious at first, but the more I think about it, the more I get it. It’s like a statement about art being whatever we decide it is. I’m not sure I’d pay $120k for it, but I do kind of admire the cleverness behind it.

I disagree with calling this art. It feels like a scam to me. Just because someone slapped a huge price tag on it doesn’t make it valuable or meaningful. There are real artists out there with actual skill that deserve more attention than a rotting banana.

Smashing an antique should never be acceptable. By anyone. Whether for religion, art or as a publicity stunt.

Once something passes a certain point in age, scientific/artistic merit, and cultural significance, I’m not sure anyone has the right to own it. It should belong to everyone, for all (practical) time.

WeiWei is a gimmickist, not an artist.

It’s funny how something so simple can stir up such big debates. To me, this just shows that art doesn’t have to be complicated or technically impressive to have an impact. It’s more about how it makes people react.

Art is subjective to the viewer, so no matter what the explanation is, it’s the audience’s own choice to interpret the artwork as how they see fit. The ones that want information can get it, the discerning ones don’t need it.

If an artist says ‘It is art because I am an artist and I say that it is’, I can simply contradict this by saying ‘I am an art critic and I say it is not art’.

Art is a social institution that has a history ie first emerged in European bourgeois society in the 18th century. The contemporary artist – to be recognised as such – has usually been trained in an art school, has received support from public museums and private galleries, auction houses, the critical discourse of art magazines etc. In other words they are empowered by the social phenomenon known as ‘the art world’. A person who is not part of this elite or specialist group – eg a home owner with a pile of bricks in her front garden – who declares ‘ this pile of bricks is art’ will not be taken seriously by anyone.

I think over intectualizing art sometimes takes away from the personal experience of the art itself.

Art is really just a fancy way of saying “I made something”.

If art doesn’t make you think, is it really art?

I think art is whatever brings you joy. If it makes you happy or gives you peace, then it’s art to you.

At the end of the day, it’s just about expressing yourself, whether others like it or not.

Art is in the eye of the beholder

This article makes a good case on the ‘what-qualifies-art-as-art?’ debate. At the ed it all depends on what viewers see as valuable to them.

I used to believe that art was mostly dependent on the artist and their skill, but throughout my academic journey, I’ve come to realize this is a somewhat “romantic” idea we carry. As the author rightly said, art does not exist in a vacuum—it depends on the viewer to make it live. We keep old masters’ paintings alive through the interest we continue to have in them. Similarly, the relevance we achieve as artists today also relies on how viewers perceive and engage with our work.

In this sense, I believe art needs a viewer to truly exist and gain meaning.

Art is what evokes a sense of awe. Everyone perceives awe in their own way