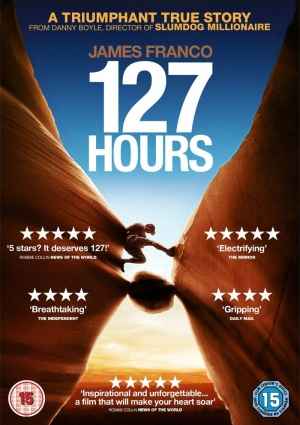

Danny Boyle’s 127 Hours: Style & (Sedimentary) Substance

127 Hours is based on the true story of Aaron Ralston (played by James Franco), who fell down a crevasse whilst hiking in the desert plains of America . His arm became lodged between a large boulder and a canyon wall, trapping him for roughly 5 days. Eventually, using his blunt pocket knife, he cut his right forearm off to escape.

127 Hours tells a story of alienation, hope, regret, salvation, and redemption. These themes are prevalent throughout all of Boyle’s films including Trainspotting, Slumdog Millionaire, The Beach, Millions, 28 Days Later, Sunshine, and Trance. Despite regularly switching genres, consistent narrative, stylistic, and thematic aspects exist throughout his filmography.

Story

In 127 Hours, Boyle’s story-telling style shares many similarities to his previous films, including non-linear structure and ‘ticking clock’, while depicting Boyle’s idea of Aaron’s past, present, and future. The characters in all of his films are problematic people expressing Boyle’s perspective. In addition, his distinctive visual style symbolises the lead character’s physical, mental, and spiritual state.

Boyle’s other films focus on his distinctive style, his illustration of the story’s overall themes, and how the films fit into particular genres. The story of 127 Hours has been well-documented and become known throughout the world. Boyle presents the story’s core elements and Ralston’s existential crisis. This is illustrated through hallucinations and memories.

To deny the directorial themes running through his films would be to miss the authorial strokes that have come to make him Britain’s dominant cinematic stylist. Windfalls of cash that act as illusory objects of desire; supine bodies telling their stories from graves or hospital gurneys; the palettes of colour that illuminate a yuppie flat, a junkie’s den, or the maze of streets through which Boyle’s life-soiled protagonists flee, exulting or panicking (Linklater. 2009).

This quote suggests that every element of Boyle’s filmography conveys specific purposes and recurring themes. One important stylistic element of Boyle’s is non-linear storytelling. He uses this to unfold a mystery and develop characters and story threads. In 127 Hours, non-linear storytelling is again used to develop the lead character’s back-story. Ralston uses a video camera to film intimate confessions for his family explaining how and why he has failed to connect with others. The film then dramatizes his past interactions with his family, friends, and ex-girlfriend.

Another important element of Boyle’s filmography is the ticking clock. The ticking clock pushes the story forward as the characters must find a realisation or place in time. In 127 Hours, the viewer is constantly reminded of the gruelling elements affecting Ralston during his journey including his mental health, the extraneous amount of time spent in the cave, and rising/dropping temperatures.

One scene depicts Ralston preparing for his first night in the crevasse. As the situation rapidly deteriorates, he must use everything to survive this pressing ordeal. As the temperature rapidly drops (shown by the on-screen title), Boyle depicts Ralston’s new ‘home’ as a video-game-esque setting, with obstacles that he must conquer. Boyle’s films stress the importance of humanity and how anyone’s character and conscience can be tested in the darkest of times. Boyle depicts how his characters’ mental and spiritual condition will determine how they approach extreme situations out of their comfort zone.

The auteur unifies all the elements of filmmaking to create a recognisable mise-en-scene. Characterisation is the human element of mise-en-scene and the primary strategy of authorship.Directors need to control every aspect of a film’s production to create a familiar work of art that can be deemed relevant.

Character

The study of authorship is not in itself a theory, only a topic or theme. It can involve a great variety of political positions and theoretical assumptions; and, like all types of criticism, it can be performed well or badly. And yet the discourse on the director-as-author has always been problematic- not only because of the industrial basis of the film medium, but also because the film director emerged as a creative type at the very moment when authorship in general was becoming an embattled concept (Naremore. 2004. p. 9).

The director’s perspective expressed through the characters. In many of Boyle’s films, the lead characters must find reasons to live; alone and disturbed by the world around them. His characters are first shown as troubled yet intriguing individuals alienated from everyone else by their flaws.

The lead characters are usually self-centred people who end up in dangerous situations. We see them interacting with a desolate environment as their emotional state becomes increasingly fragile. The non-linear storytelling helps us discover why and how they have reached this point. Boyle establishes that Ralston, before he became trapped in the canyon, loved himself more than other people. Ignoring his mother’s phone calls, he wakes up early in the morning, packs his gear, and sets out on the road to his destination.

In the title sequence, Boyle places three unrelated images together which contain events involving mass groups of people. They include a marathon, a crowd in a stadium, and a group of bicyclists. These vibrant shots are compared to and contrast scenes of Ralston in his darkened house. In this montage, Boyle emphasises Ralston’s loneliness and spiritual journey. In the last third, the characters prove they are sympathetic, courageous, and humanistic; learning to save themselves, others, or even humanity itself. Before the climactic arm-cutting scene, Ralston realises that the final act of courage and survival he will make is the most gruelling and violent he could imagine.

He realises that he’d rather survive and make amends for his mistakes than die in the present. Cutting through the intricate wiring of his forearm, Ralston’s pain is increasingly evident. Like many of the character studies/psychological dramas Boyle has created, 127 Hours builds to one of the bravest and most graphic actions that anyone could achieve.

Style

A film can be seen as an auteur’s signature written on the screen. The director’s composition and direction creates the world within the camera. Auteurs can express thoughts, desires, or themes, across a body of work, by using their style. Boyle has experimented with and developed his unique visual style throughout his career.

Once it was understood that a film was a product of an author, once that author’s “voice” was clear, then spectators could approach the film not as if it were reality, or dream or the dream of reality, but as a statement by another human being (Monaco. 2009. p. 463).

This quote suggests a director’s style can be seen as a way of presenting their artistic statement and prowess. Boyle illuminates peculiar aspects of existence with as many sensory and technical elements as possible. His previous films have used fantastical elements to tell a larger-than-life story. With Sunshine, 28 Days Later, Trance, and Millions, he uses bright colours and intricate camera movements to immerse the viewer in a fantastical narrative. With 127 Hours, the editing, camerawork, and soundtrack create steady pacing and establish tone. After the boulder has trapped his arm, the tone suddenly switches from fun and kinetic to dark and dramatic.

Being a true story, 127 Hours does not allow Boyle to create an epic sense of scale or a fantastical environment, and he is somewhat restricted to key moments/elements of the situation. He uses camerawork and sound to illuminate claustrophobic aspects of this ordeal. The location becomes very tightly limited to the crevasse. Stuck in the crevasse, Boyle films the space in many different ways using low and high camera angles. When filmed in high angle, Boyle emphasises Ralston’s isolation. When filmed in low angle, however, Ralston seems to understand the gravity of his situation and determination to escape.

The final third presents Ralston’s detachment from his narrow-minded and disastrous view of existence. The visual style here depicts Ralston’s physical and psychological shifts. This uncomfortable scene establishes the intensity of violence and despair. He accepts his new responsibilities and makes the toughest decisions imaginable. Boyle chooses close up shots to illustrate the toll that Ralston’s own actions are taking on his body.

The camera switches between multiple high and low and angles during this sequence. The editing cuts quicker and quicker as the camera shakes with each physical cut Ralston makes through each tendon. The soundtrack enhances the emotional effect with an eerie, sharp sound whenever the knife cuts through. Boyle presents the physical, mental, and emotional distortion. This distortion also reflects the character’s rapidly changing ideologies. Boyle often uses violent incidences to change the lead character’s perspectives on reality and the human condition.

Conclusion

Authorship focuses on the strength of the artist. They can use the tools at their disposal to create a recognisable style and unified mise-en-scene. Boyle’s style is based on uncovering the most touching and visceral aspects of his characters and story. In 127 Hours, Boyle applies his style despite several conceptual differences between it and his other works. Boyle focuses on how Ralston’s past plays into his current ordeal.

The characterization in 127 Hours, like many of Boyle’s films, focuses on a young man who is philosophically lost due to bad luck or immoral behaviour. Throughout 127 Hours, Ralston is depicted as a cheerful young man and ashamed fool. He must overcome overwhelming odds to survive and make amends. Boyle’s visual style uses editing, camerawork, and sound to establish the harshness of Ralston’s situation, creating a unique and graphic interpretation of this story.

Works Cited

Disclaimer: Curtin University, 2013.

Boyle, Danny (producer/director)., Colson, Christian(producer)., Smithson, John(producer). (2010). 127 Hours. Fox Searchlight, USA. 94 mins.

Linklater, Alexander. (2009). Danny Boyle Profile: A Film Director in A Class of his Own. The Observer. The Guardian. Guardian News and Media Ltd. Retrieved from http://www.guardian.co.uk/film/2009/jan/04/danny-boyle-interview-slumdog-millionaire

Monaco, James. (2009). How to Read a Film: Movies, Media and Beyond. Fourth Ed. New York: USA. Oxford University Press inc.

Naremore, James. (1999). Authorship, In Stam, R. and Miller, T. (Eds.), A Companion to Film Theory (pp. 9-24). Blackwell Companions in Cultural Studies, Malden, Mass.; Oxford: Blackwell.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

James Franco was excellent in this film. His performance left me completely dumbfounded. Surely he is one of the greatest actors of our time? I have the wonderful feeling that he has so much more to give.

He does fit with this kind of film; I will say this.

It was an amzingly shot film, inspiring, gruesome, awesome.

this film has some nice touching and thrilling moments but its essentially a half hour film padded out to fill 90 mins. its really not the stuff that features are made out. there just isnt enough material there to make it seem like they were really strapped for ways to fill up the necessary time. its also somewhat shallow – boyle didnt create enough of a life for the lead character beyond his predicament for us to really get to know him better. buried was far from perfect, but that did this sort of ‘one man trapped’ thing better.

Thomas, thank you for your perspective on 127 hours.

127 Hours was a very interesting movie, basically because not much happened during it, but I wasn’t bored at all. It’s a remarkable story about courage and strength, and I really liked the use of the video camera entries to tell Aaron’s story. At one points he starts to lose hope in ever being rescued, and we feel bad for him. He didn’t deserve this to happen to him, and yet when he finally realizes he can escape, but without one of his arms I was desperately hoping he would cut it off.

The final scene in the film is the most powerful, especially with the score by Sigur Ros. I was so happy when he finally exits the cave, and felt motivated and hyped. I was so happy to see that he finally made it out alive, and that he was strong enough to survive. Even when we realize towards the end that he still lives his life to the fullest every single day, it gives us motivation to never give up and keep a positive attitude on life.

The longest cautionary tale of 2010.