Are Disability and Death Inextricable?

According to the CDC, about 15% of Americans live with some form of disability. However, many more than 15% of Americans display attitudes that indicate they believe people with disabilities have diminished quality of life. Disturbingly, this includes the people with disabilities themselves. According to Exceptional Children: An Introduction to Special Education, just 20% of people with disabilities have achieved any level of independence 5 years after high school, and 75% of people with disabilities are unemployed or under-employed (Heward et. al). Heward also points out that many students with disabilities who are consigned to special education find that their “education” does not translate to real-world experiences. Thus, when asked, they report feeling “lost” and “unimportant” (Heward et. al). Perhaps this is why, on social media outlets like Quora, users can still find stories of parents terrified to raise a disabled child. Perhaps it’s why the abortion of American babies with disabilities like Down Syndrome remains at 90%, and why abortion of babies with cerebral palsy and other physical disabilities remains at 40-50% (Zhang 2020).

Of course, not very many people would express these feelings outright. To do so is not “politically correct” or “inclusive.” Yet for years, even and especially in recent decades, real life and the media have shown a cloaked, yet prevalent attitude. They have shown most people believe disability and death are inextricable, and that death is the most natural and merciful course for disabled people. The sooner that death can happen, the better.

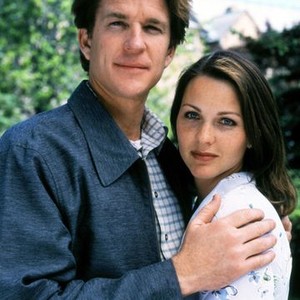

Just one of the most egregious examples of this, though certainly not the first, is the film Me Before You. On June 3, 2016, Me Before You opened in American theaters. Based on JoJo Moyes’ bestselling novel, Me Before You tells the story of Louisa Clark, “an ordinary girl living an exceedingly ordinarily life” (Moyes). Louisa takes a job as a caregiver for Will Traynor, a former world class athlete and world traveler who lost it all after an accident left him “wheelchair bound” (Moyes). Me Before You, the book and movie, allegedly chronicle the relationship between the bitter Will and the ordinary (abled) Louisa, who treats him differently than anyone else, but not because of his wheelchair.

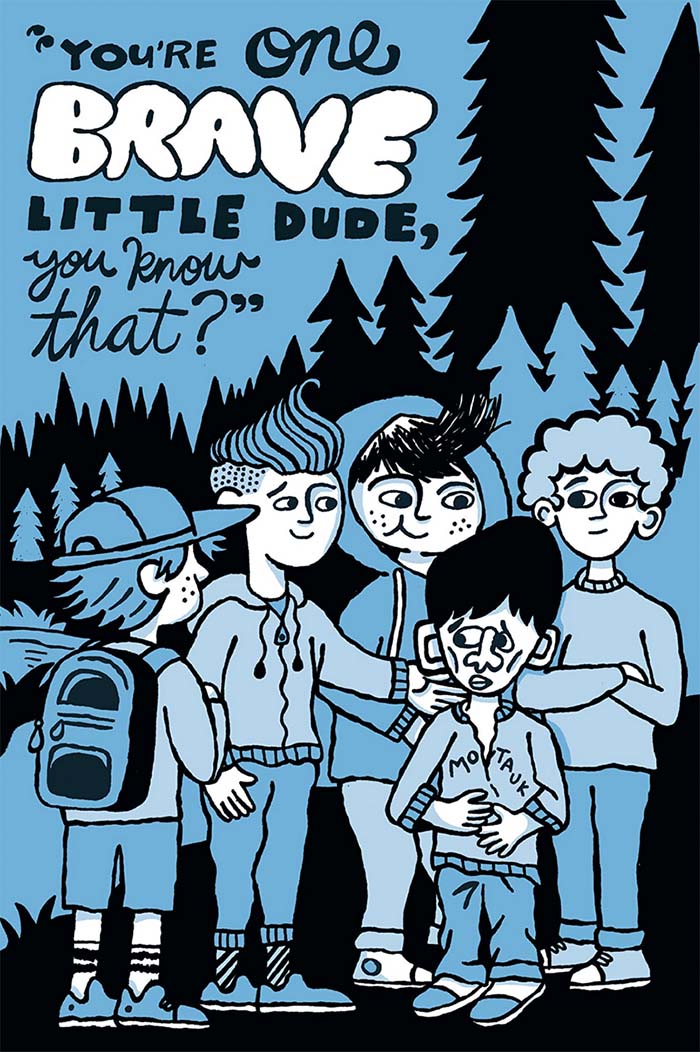

However, people with disabilities (PWDs), professional advocates, and reams of others have protested Me Before You. Despite its premise, this story is less about a deep, inter-abled relationship than it is about ableism. Specifically, Will ends up committing suicide. According to the staff of the RespectAbility website, Will’s suicide makes Me Before You a “disability snuff film” that promotes the idea it’s better to be dead than disabled.

John Kelly, New England regional director of the organization Not Dead Yet, pointed out the myriad flaws of this narrative in an interview when the film first released. “JoJo Moyes admits she knows nothing about quadriplegics,” said Kelly, who has the same type and level of injury as character Will Traynor. “Yet her ignorance is allowed to promote the idea that people like me are better off dead. We are not ‘burdens’ whose only option is to commit suicide” (Kelly 2016). Other advocates agreed. “We’re sick of society saying…you should just go and die,” Stephanie Woodward of Greece, NY’s Office of Disability Rights said. “People with disabilities want to live.” These and other sentiments have opened the conversation about disability, death, and whether they are synonymous, more than ever before.

Life vs. Quality of Life

Many people outside the disability arena would argue people with disabilities are living. This writer herself lives with cerebral palsy and Asperger’s syndrome, and has encountered many instances of ableism being pooh-poohed on social media. In one case, she saw a commenter who wrote, “I have mild cerebral palsy and have never [experienced ableism.]” A responder wrote, “Probably because of onesies and twosies trying to [make a big deal.]” Others on the thread decried ableism as “another -ism,” an invention of “woke” politics, and an excuse for victimhood. This includes other disabled people, one of whom called ableism “a steaming pile of crap.”

These arguments aside, few if any people would actually say they want people with disabilities to “go and die.” A minority can certainly be found on social media, usually on Reddit or similar sites, operating under hashtags like #unpopularopinion. There, they revel in calling disabled people “retards” and other slurs, saying they are not useful to society, and mocking anyone who speaks of disabled people with compassion or regard.

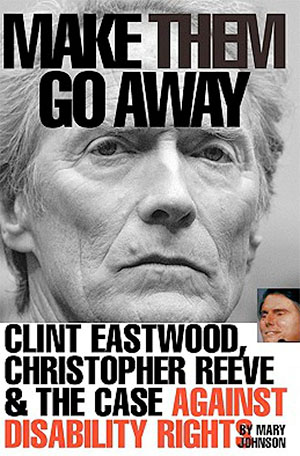

Yet as author Mary Johnson puts it, most of America, Britain, and Canada have accepted the narrative “help the handicapped.” In her book Make Them Go Away, Johnson goes on to explain “help the handicapped” sounds benevolent in theory. Yet underneath, the narrative still presents disabled people as fundamentally different types of humans, who must be helped and cared for if they are to experience any life quality at all. The problem is, that quality of life, and the level of quality, is usually determined by non-disabled people. These are usually some form of caregiver, whether a family member, doctor, therapist, teacher, or social worker.

Untangling Disability Representation from Death

The struggle then, becomes how people with disabilities and their supporters can present disability in the most positive light possible. The goal is communicating, “This population needs and deserves ultimate quality of life.” But before this argument can be understood and accepted, people with disabilities must be represented. Representation often starts in fictional media, including books and movies. As the twenty-first century progresses, more media creators are giving consumers vibrant, three-dimensional, and living characters with disabilities. More creators are also trying to avoid plots wherein characters with disabilities (CWDs) commit or contemplate suicide.

However, a close examination of past and recent media, including some “classics,” indicate death and disability are still tangled in each other. That is, most if not all CWDs face the threat of death, be it physical, mental, emotional, or some combination. Physical death in particular seems to stalk CWDs more than able-bodied characters, even if physical death isn’t imminent. One could argue even the most well-developed CWDs haven’t been and perhaps cannot be represented without death.

The next question then, is whether the use of death in disability-based stories is always a bad idea. Disabled or not, most protagonists face some form of death as detailed above. The threat of death makes living readers identify with, remember, and learn from fictional characters. When the characters are disabled though, death must be handled differently so the narrative doesn’t become “better dead than disabled.”

The best way to elucidate how CWDs can triumph over death in their stories lies in examining good and bad examples of facing death. In so doing, we will focus on how fictional media should learn from these examples. We will discuss how future disability stories can redesign the “death” concept while avoiding the “better dead than disabled” message, or implying people with disabilities “need” to die. We will focus on how creators can reshape death so that, like their abled counterparts, disabled characters can triumph over it and live.

For the purpose of our discussion, we will use “person or people with disabilities” or “disabled people” to describe the character population. The real-life disability community has expressed individual preferences for both terms. We will also use “abled” or “non-disabled” to refer to non-affected characters, and discuss “ableism.” Ableism is discrimination against disabled people, including systemic attitudes or biases that show preferences for abled, unaffected minds and bodies.

Death of Disabled Identity

Sometimes characters with disabilities face physical death, but don’t experience it. Instead, they experience “death of the disabled body.” That is, the body doesn’t die, but it is cured of disability in some way, so the disabled body “dies” and becomes “whole.” Often, cure or “death of disabled body” is presented as a CWD’s only hope for true happiness. The cure occurs at the climax, where as TV Tropes puts it, the CWD “throws off the disability” for good. The audience is left with the impression that now, without a disability, this character can live as he or she was meant to. The fact that part of this character’s identity has “died” is not acknowledged, except with a cheery, “Good riddance.”

Many classic works and their creators use this trope. At times, it’s milked to the hilt. According to Professor Lois Keith, the tropes were extremely common in the Victorian or Edwardian eras, in children’s literature specifically. Keith explains the “aim” of children’s literature during these eras was “largely didactic,” meant to teach children “how to overcome selfishness or a too-strong will, or to conform to traditional roles and gender expectations” (Keith 2004). Failing that, children’s literature was made up of “warm family stories.” Such expectations may be why classic authors fell back on “death of disabled body” rather than actual death of a disabled character. That is, killing any innocent character, particularly a disabled one, in a warm story meant to teach children moral lessons, would’ve been counterproductive. If anything, it might have meant another death–of the authors’ careers. Perhaps then, these authors went as far as they dared within the framework of their era, creating a different type of death.

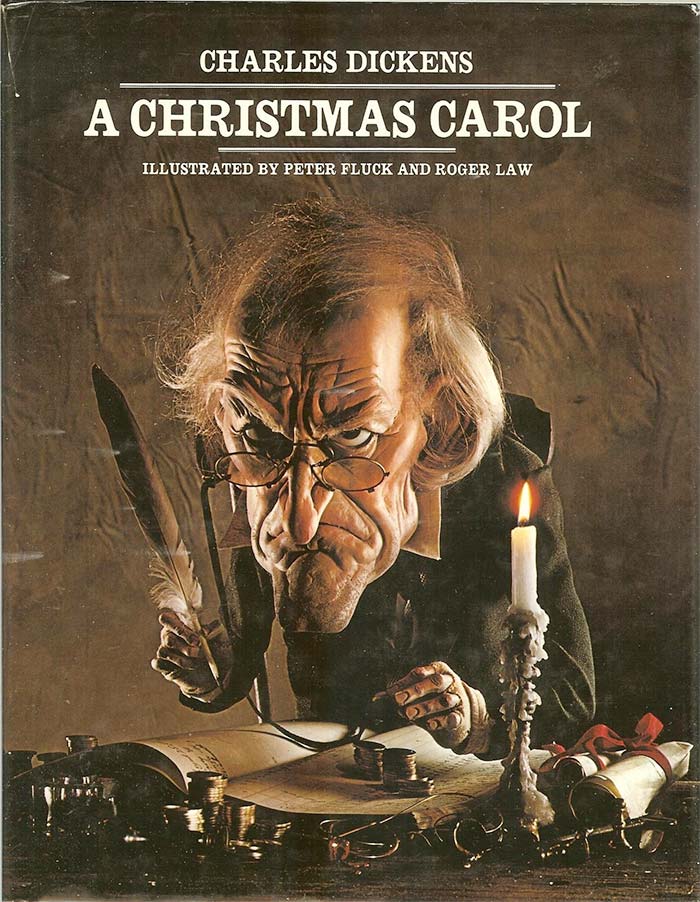

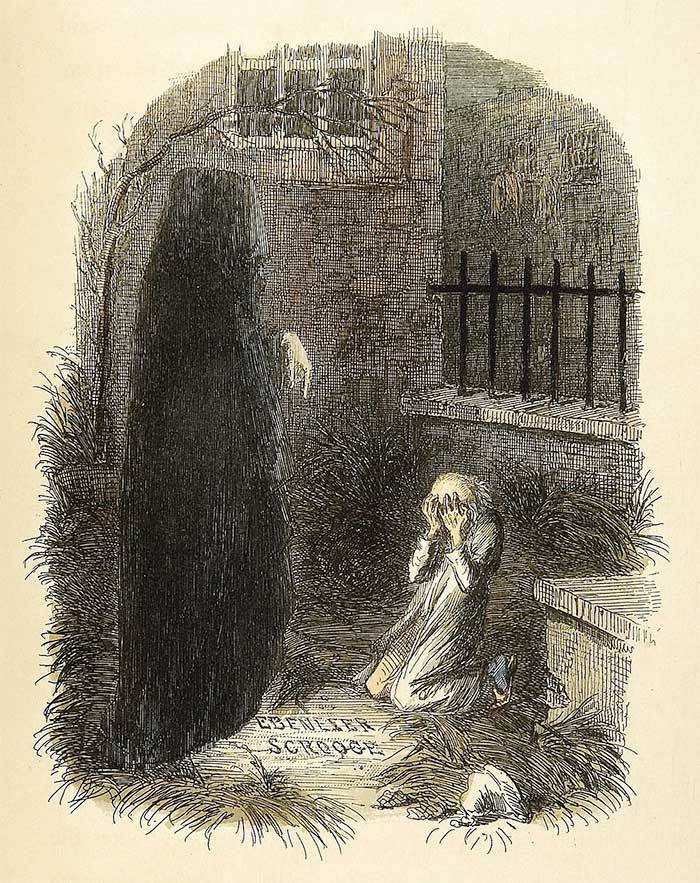

A Christmas Carol

Indeed, one of the most famous examples of the physical death or death of disabled body tropes is Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol. The “holiday ghost story” was first published in 1843 and hasn’t been out of print since. One of the elements that makes it such a classic is the juxtaposition of cruel anti-hero Ebeneezer Scrooge with Tiny Tim Cratchit. As his name implies, Tim is an undersized boy, one of many victims of Victorian London’s ubiquitous poverty. Unlike Scrooge, Tim is raised in one of those warm and loving families Lois Keith discusses. He’s kind, unfailingly submissive, forgiving, and constantly spouting nuggets of wisdom. Tim is also disabled and in fragile health. His disability isn’t named, but he walks with a crutch for short distances. Otherwise, his family carries him.

Tim’s father and Scrooge’s clerk Bob Cratchit implies that someday, Tim might “throw off” his disability. In the George C. Scott film adaptation, father and son stop at a local hill on the way home to watch other, abled children play in the snow. “You’ll be there one day,” Bob encourages his son, and Tim agrees, saying he feels stronger each day. However, viewers and readers soon learn this is a pipe dream. As the Ghost of Christmas Present warns Scrooge, “if these shadows are unaltered by the future, the child will die.” In other words, if Scrooge’s avaricious behavior doesn’t change, Tiny Tim’s life is forfeit.

Disabled, Yet Morally Perfect

One could argue the Ghost’s warning isn’t only about disability. After all, Tiny Tim is the first character Scrooge has shown any concern or kindness toward. It would make sense for the possibility of his death to shake Scrooge up when nothing else could. In addition, Tim lives in an era where poverty like the Cratchits’ often meant premature death, disability or not. Even his nickname, “Tiny Tim,” is arguably not patronizing because well, the boy is a tiny kid. The nickname endears him to readers and viewers. Tim reads as the little brother or longed-for “last baby” every “warm and loving” dad wants to hoist on his shoulders, every mom wants to cuddle, and every sibling wants to protect.

However, these justifications for the threat of Tim’s death don’t hold up. Poverty isn’t a good reason because, struggling though they are, the Cratchits read as Victorian London’s version of lower middle class. They can comfortably provide for several children, if on a tight budget. Two of those children are of working age, skilled enough to get secure jobs, and treated well in them. Thus, it makes more sense to blame Tim’s premature death on disability. Said death might change Scrooge, but readers might well ask, does the death of an innocent child, and a minority at that, make Tim’s arc fair? Readers can even argue, blaming Scrooge for the death of a disabled child he barely knows does nothing for his character. It only makes him more a cardboard, irredeemable villain. Worse, such a move destroys the story’s theme, that everyone, regardless of position or ability, is capable of the embodiment of Christmas spirit.

In the end, Tiny Tim does not die, and Scrooge becomes “a second father” to him. In some adaptations, he’s shown running for Scrooge to sweep him up in a hug at the end. In other words, Tim is not dead, but his disability died. Yes, in his era, the disability was more an obstacle than anything. Still, the message remains, a disabled identity is not the ideal. If a reader wanted to be harsh, they could say the message is, “Problems like disabilities only lead to death, which ruins good things like kindness, love, and Christmas.”

The Secret Garden

A similar and more disturbing example of “death of disabled body” occurs in Frances Hogsdon Burnett’s The Secret Garden. Published in 1911, this children’s classic is Edwardian, not Victorian, but its didactic nature remains. Since The Secret Garden is geared more toward children, and not whole families like A Christmas Carol, the didactic nature is arguably more pronounced. Spoiled, “imperious” characters like Mary Lennox and her cousin Colin Craven exist in part to warn children away from imitating their behavior (Burnett). Better, Colin is disabled while Mary is not, which sends the message that spoiled, bratty behavior is not contingent on ability level. However, most of the lessons and themes in the book are tied to disability or the death thereof.

Disability does not appear in The Secret Garden until the second half, when Mary discovers Colin. Until then, she had associated Colin with the mysterious crying she heard echoing in the halls of her Uncle Archibald’s mansion, Misselthwaite Manor. One night, Mary gets up the courage to investigate, and finds Colin in apparent distress. According to Colin, he has struggled with illness since he was born. In the 1993 film version, he tells Mary he has spent his entire life in his bed. Mary’s maid Martha confirms this, noting that Colin was an extremely weak premature baby everyone thought would die. “His father couldn’t bear losing [Colin] too,” Martha says. Indeed, childbirth killed Uncle Archibald’s wife, and he was determined to spare himself and his son any more suffering.

Archibald’s determination has given Colin a dismal present and uncertain future. Colin believes he will inherit his father’s “hunchback” and die young, deformed, and an ultimate object of pity. He’s not supposed to know this grim prediction, he tells Mary. But Colin’s nurse, housekeeper Mrs. Medlock, and the household staff haven’t watched their tongues around him. The doctor has also been vocal about Colin’s prognosis. “[He] is my father’s cousin…he will have this house after my father. I shouldn’t think he wants me to live,” Colin says in the 1975 BBC miniseries. Indeed, Dr. Craven doesn’t actively hasten Colin’s demise. Yet like many doctors of his era, he’s quick to offer vague diagnoses such as “nerves,” a plethora of prescriptions, and less-than-hopeful outlooks, especially for disabled or chronically ill patients.

Disabled and Doomed to Misery

Physically and psychologically ineffectual, Colin asserts power the only way he can. He uses his position as the heir, and the pity others direct at him, against the other Misselthwaite residents. As Colin explains to Mary, he must be given anything he asks for, and “no one dares make me angry. If I’m angry, I feel ill.” The staff is terrified illness will send Colin spiraling toward his deathbed, so they don’t correct or discipline him in any way. By the time readers meet him then, Colin is more spoiled and selfish than the imperious Mary ever was, and that’s saying something. Unlike Mary for instance, Colin doesn’t hide the extent of his nature behind surly comments and cold silences. He’s more apt to throw kicking, screaming tantrums on the level of a toddler, often because he felt phantom pains or lumps on his back.

The biggest difference between Colin and Mary though, is the latter has had exposure to physical, emotional, and social outlets, because she is able-bodied. Mary is able to leave the house whenever she wants. She spends most of her time exploring the grounds and gardens, as well as discovering the titular secret garden. She devotes her energy to helping her garden grow, thus helping herself grow physically. As for her emotional and social growth, Mary finds that in caring people like Martha, Dickon, and Ben Weatherstaff, as well as a few animal friends like the garden robin. Perhaps because Mary is healthy and able-bodied, the people around her aren’t cowed at her attitude. Some offer gentle or cleverly disguised correction; the BBC miniseries, for instance, adds a servant named John who teaches Mary to say “please” and “thank you” because “it’s the custom” in England. Others, like Ben, offer the same grumpy reception Mary gives them, in a sort of reverse psychology. Still others, like Dickon, offer patience and unconditional friendship based on mutual interests, like a love for flora and fauna.

By the time Mary meets Colin, she, the abled one, is flourishing, while Colin, the bedridden or “wheelchair-bound” one, is withering (wheelchair-bound, in this case, because he is in every sense “bound” to the “invalid” label the wheelchair symbolizes). This in itself is a problem, especially when Colin gets worked into “hysterics.” Mary tells him off for the tantrum, as well she might. After all, there’s nothing physically wrong with Colin except weakness, and he’s manipulating the staff to the hilt. But the scene also communicates disabled people are all prone to act like Colin does. It also implies sickness is mostly inside the person’s head.

Indeed, Frances H. Burnett leans heavily on this idea during the last third of The Secret Garden. Burnett was a devotee of Mary Baker Eddy, a Christian Science practitioner who did believe all illness was psychosomatic or a matter of not having enough faith. Colin’s religious faith isn’t explored, but once Mary convinces him to go into the secret garden, his health perks up. Within days, he’s walking again; the 1993 film shows him climbing stairs, and the miniseries has him proclaim, “I’m going to be an athlete!” The last scenes of the book and adaptations show Colin walking or running, “as strongly and steadily as any lad in Yorkshire.”

One could argue Colin’s experience isn’t “death of disabled body,” because he was never disabled. His experiences in the garden prove everything was in his head. However, Colin’s experience is not only a physical “disability death,” but almost a complete cold-blooded murder of the disability experience. That is, Frances H. Burnett first implies disability is a matter of personal weakness, whether that’s emotional or spiritual, and easily cured. She next implies disabled people should be cured because otherwise, they’re apt to wither into themselves and take out bitterness or fear on others. Failing that, they’ll be pampered brats.

Finally, Burnett through Colin implies a person can go from disabled–thus unable–to completely able in every sense, in record time if they believe enough and “grow” enough. No room is left for the physical realities of disability or the possibility that a disabled person could retain his or her disability and still excel, accomplish, and grow. Perhaps most disturbingly, no room is left for the possibility of a disabled person being something between an angel and a brat–in other words, a typical, ever-evolving person. Anything like this is completely choked out like a weed in the garden of mind over matter.

Pollyanna

Published in 1913, Eleanor H. Porter’s novel Pollyanna is neither Victorian nor Edwardian (the Edwardian Era ended in 1910). It’s also American, whereas the previous two novels in our discussion were British. However, Pollyanna maintains the didactic nature of children’s stories from those eras, as well as the didactic presentation of disability. In fact, protagonist Pollyanna Whittier’s portrayal is so saccharine, her name is synonymous with unrealistic optimism. The treatment of disability in her story proves the “death of disabled body” trope easily jumped across the pond.

Interestingly, Pollyanna doesn’t start out disabled. In many ways, she’s the epitome of an “all-American girl”–able-bodied, intelligent but not overly so, a charitable minister’s daughter, Caucasian, and blonde. (Hayley Mills’ 1960s Disney portrayal adds ringlets and blue eyes). She is an orphan, which knocks down her status in the eyes of Harrington Town. But considering she’s also the niece of wealthy town founder Polly Harrington, the town doesn’t openly scorn her as they might other orphans. Other people do question Pollyanna’s insistence on being “glad” about everything, but more as a curiosity or annoyance than an example of bad behavior. If anything, Pollyanna is as close to perfect as a 1910s children’s lit protagonist can get. Specifically, she’s the perfect person to deal with Harrington’s many curmudgeons, including those with illnesses or disabilities.

Pollyanna wastes no time spreading her optimism through the Glad Game, a mentality her father taught her. As Pollyanna explains it, the Glad Game is a personal challenge to find something worthy of gladness in any situation. Her first example actually hearkens back to disability. When a pair of crutches showed up in a missionary barrel instead of the doll Pollyanna wanted, she and Dad decided to be glad she didn’t need the crutches. Voila, all disappointment over the doll forgotten. Pollyanna continues with these examples throughout the book and film. She’s glad Aunt Polly forced the two of them to share a room, because neither Pollyanna nor her aunt will have to be lonely. She’s glad she can listen to one of the Reverend’s hellfire and brimstone sermons on Sunday, because “it’ll be a whole week before Sunday comes round again.” She’s glad she’s never had ice cream, because after all, she doesn’t know what she’s missing and can’t be disappointed.

Some people, including Aunt Polly, dismiss the Glad Game as childish, annoying, and forced. Others, however, soon warm to Pollyanna’s ideals, partially because Harrington is rather cold and legalistic under Aunt Polly’s rule. The Reverend, for instance, determines to start preaching “happy texts” from the Bible, and tells Aunt Polly she was wrong to tell him what to preach. Household maid Nancy looks forward to Pollyanna’s “glad” observations, and soon becomes a confidante to the little girl. The 1960s film adds positive changes for sour-faced maid Angelica and a neglected, cynical orphan named Jimmy Bean.

However, Eleanor H. Porter seems to want readers to focus most on how the Glad Game affects people with physical disabilities, or “disabling” attitudes. One of the most frequent recipients of the Glad Game is Mrs. Snow, Pollyanna’s elderly and bedridden neighbor. Nancy brings food to her almost every day, but explains Mrs. Snow is never satisfied with what she’s given. If she’s brought chicken, she wants lamb’s broth. If she’s brought lamb’s broth, she’ll say she wanted calf’s-foot jelly, and on and on. Additionally, Mrs. Snow seems obsessed with dying. When Pollyanna first meets her in the film, she’s choosing the lining for her coffin. It’s unclear whether Mrs. Snow is a hypochondriac or truly ill. However, as with Colin Craven, everyone treats her as “an invalid”–disabled. And in the world of Pollyanna, again,”disability” = bad attitude borne of no quality of life. Mrs. Snow only becomes more pleasant and docile after Pollyanna teaches her the Glad Game, and Snow “warms up” to the idea. In a nutshell then, Pollyanna, an able-bodied person who conforms to the expectations of her age and gender, and maintains a pleasant attitude, becomes the hero for another woman who does not conform. In fact, Mrs. Snow can’t conform to her gender expectations because of illness and disability. Therefore, Pollyanna reads as her best hope for quality of life.

A new reader or viewer might wonder if Pollyanna’s Glad Game and associated philosophy could ever fail her. They do, after Pollyanna sustains a disability. She falls when climbing a tree and sustains a spinal cord injury, leaving her paralyzed from the waist down. The film adds this happened because Pollyanna sneaked out to a charity fair Aunt Polly forbade her to attend. Pollyanna would’ve gotten back into her room with no one the wiser, except that she was juggling the beautiful doll she won in a fishpond game. Her attempt to save the doll made her lose her balance. This adds an element of selfishness to Pollyanna’s existing misdeed. It implies paralysis is a direct punishment, perhaps from God Himself. Such an implication might be the reason Pollyanna becomes listless and depressed after her injury. Recall she is a minister’s daughter and, though she doesn’t read as a “Christian” character, she embodies idealized virtues of the faith. Punishment or not though, Pollyanna cannot deal with her injury. She can’t find anything to be glad about when she’s on the receiving end of the tragedy of disability.

Disabled and a Martyr

Of course, the idea of disability as tragedy is not Pollyanna’s fault. As with the other protagonists we’ve studied, she’s simply growing up in an era when people with disabilities had few options. Again, death was one of the only options. While Pollyanna isn’t at particular risk of death, one could argue her depression will lead to a downward spiral. In her era, suicide would be even more taboo than it is today, but she could refuse medical treatment even if the adults in her life pressed hard for it. She could stop eating or embrace a short-lived role as an angelic “invalid” who “learned her lesson” from trying to save a doll. She wouldn’t be the first protagonist to do so, either; other paralyzed girls like Klara from Heidi or Cousin Helen from What Katy Did, fit this role. Era conventions aside though, Pollyanna is set up to become yet another CWD who has no agency. She has made her last self-determined decision, and will apparently pay for it by becoming a victim.

As with Colin Craven, how much of this Pollyanna brings on herself is debatable. Yet with Pollyanna, this facet is even worse. She’s not a spoiled brat, so the implication is, “Good children, good people, do not deserve disability.” Her depression is handled in a way that disrespects people living with the real condition, in any era. And because Pollyanna is a girl in a pre-feminist time period, the implication is, “Disability is a shame, but this brave little girl can handle it. It won’t keep her from conforming to the expectation of submission.”

The biggest complaint modern readers and viewers have against Pollyanna though, is that Pollyanna doesn’t keep her disability. A “simple” operation will help her regain full use of her legs. In the film, we see Aunt Polly and her fiance-to-be Edward Chilton carrying Pollyanna downstairs to meet the train for the hospital, the whole town grinning and cheering her on. Pollyanna herself has perked up, too. She will get to “throw off” her disability, and so has already “thrown off” her depression. Once her legs are fixed, her “glad” identity can return and keep brightening the lives of those less “glad” or fortunate. Better, Pollyanna faces her journey and surgery knowing she has already made a huge difference in her new town. The people around her are happier and friendlier, especially toward one another. Those in authority, such as the town doctor and minister, no longer use said authority to intimidate or discourage others. Although it took longer than anything else, Pollyanna’s Glad Game has permanently softened her aunt’s heart, so the latter can embrace life again (through marriage and domesticity). Pollyanna has ensured others become their ideal selves and now, having learned the needed lessons of disability, can become her ideal self.

People with disabilities and their abled allies are anything but glad for this happy ending. Some of their reasons are familiar, such as the way Pollyanna presents disability as undesirable, and those with it as pitiable, depressing, or unworthy of empathy (perhaps, unworthy of life). But Pollyanna goes a few steps further. It presents disability as a punishment to the one with it, and the only way for that person, or any person, to achieve permanent “goodness.” According to author Kayla Whaley, Pollyanna also presents “acquired paraplegia” as the only acceptable form of wheelchair use in particular (Whaley 2016). In Pollyanna’s case, acquired paraplegia ups the drama in her otherwise warm and comforting, but saccharine and low-stakes story. In addition, acquired paraplegia gives Pollyanna a “built-in journey” and reminds readers of her book that “[disability] can…happen to you!” (Whaley 2016). Pollyanna doesn’t have to work for anything. She doesn’t necessarily have to learn anything, because despite rationalizations that disability made her “better” and “gladder,” she was already an ideal child. She simply has to put up with disability until she can throw it off–in this case, until she can be rescued via operation.

Complete Physical Death

The second type of physical death a character with a disability (CWD) may face is physical death of both body and soul. Here, the disability is not “thrown off.” The character loses not just identity, but life itself. The implication is that life with a disability is a lesser life, one of endless pain and suffering. In some works, the implication may be that disability is unacceptable because of the environment. That is, if “survival of the fittest” is at play, people with disabilities are obviously not strong or fit enough to survive, so they would naturally die off. If an abled character sustains disability through combat or illness, he or she is likely to perish. However, the disability, not the surrounding cause, will be blamed for the character’s death.

The placement of complete death second in our discussion is intentional. Although the specter of death hovers around almost all characters with disabilities in older works, it was not exactly common for authors to actually kill off disabled characters until after the eras we have covered. Before then, killing characters with disabilities may have gone against the conventions of the “warm family story.” Since so many CWDs were presented as saintly, and since so many were children, it may have seemed cruel to kill them, either because they were so good or had so much life left to live. However, fiction became much grittier after the Victorian and Edwardian periods. Works tend to present all of life’s realities, including death of the weak or disadvantaged. This trend can be found in older, classic works just like “death of disabled body” can. But while the stereotype of the saintly, sickly disabled person in danger of the Grim Reaper has faded, complete death of CWDs can still be found in modern works as well.

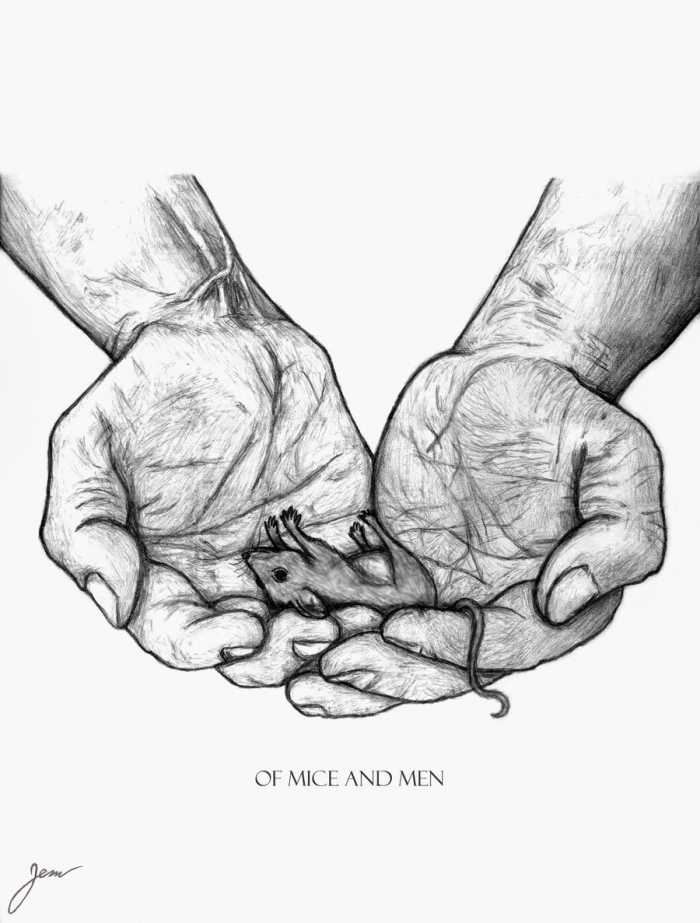

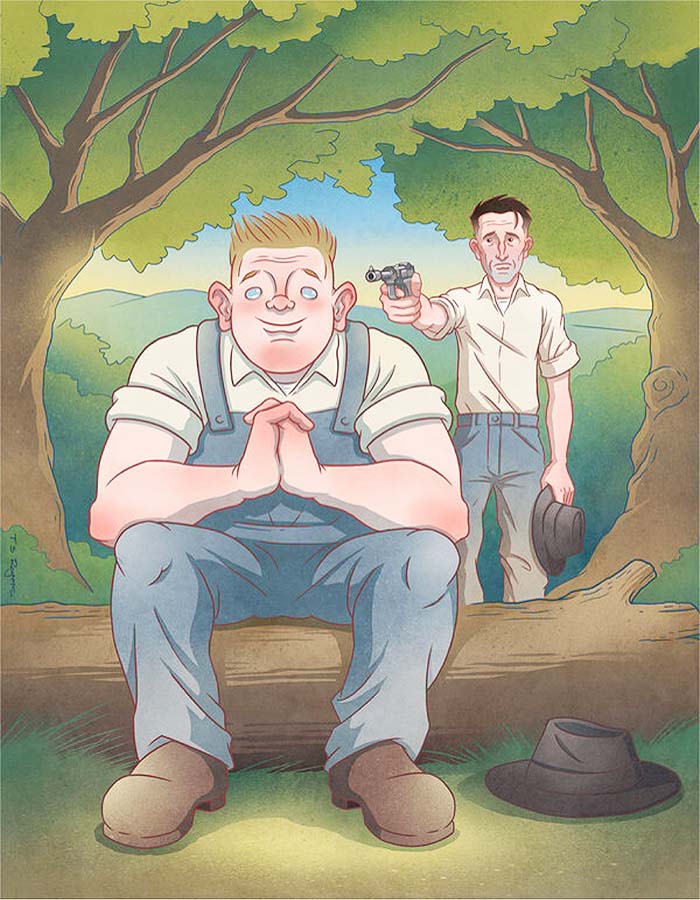

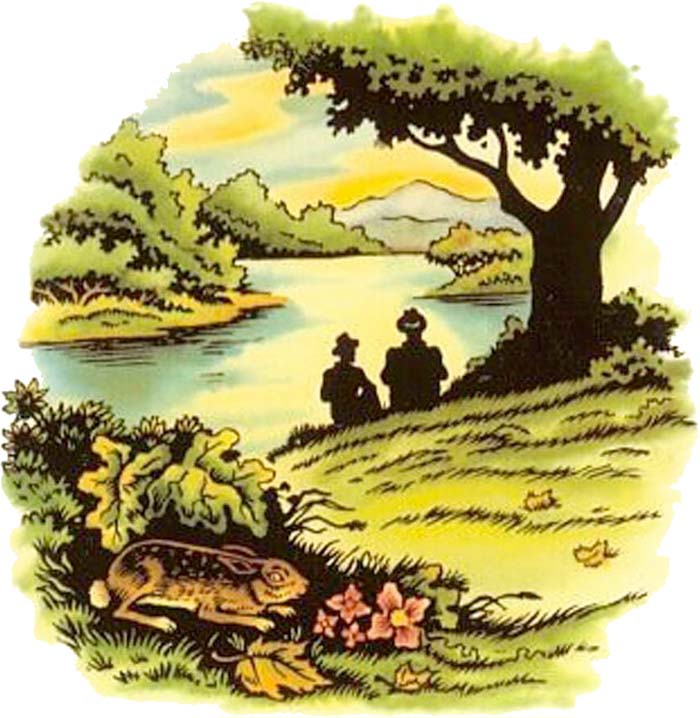

Of Mice and Men

Published in 1937, John Steinbeck’s novel is probably one of the best-remembered examples of complete death for a CWD. It’s a huge departure from the archetypes and tropes we’ve seen thus far, not only in terms of characters and plot, but creator. According to nobelprize.org, Steinbeck was a fan of “rough and earthy humor,” perhaps because of his experience “[working] his way through college and…[establishing] himself as a free-lance [sic] writer,” in an era when writers were guaranteed hardscrabble existences (Nobelprize.org). Steinbeck’s novels delved deeper into “aggressive social criticism” than many of those that predated them. But Of Mice and Men doesn’t read as a criticism of how people with disabilities were treated in the 1930s. If anything, the novel makes Steinbeck “complicit” with the eugenics-based thinking of his era (Sarah Catherine Holmes). Holmes, for instance, argues Of Mice and Men is proof of Steinbeck’s “concern with the crisis of masculinity eugenics fostered” than the lives of real people with disabilities (Holmes).

Steinbeck’s novel, and the accompanying 1992 film, center on George and Lennie, two American migrant workers who’ve come to California seeking work during the Great Depression. They dream of starting their own farm in a few years, or at least George does. Lennie doesn’t have a good grasp on what farming entails. All he knows is, George promised him when they had a farm of their own, Lennie would get to tend the rabbits. Lennie is an “imbecile giant” (Nobelprize.org). According to author Clare Lawrence, he presents with “learning difficulties and…many characteristics of autism” (Lawrence). Lennie is also a stereotype of intellectual disability. His speech is thick, impeded, and childlike; he’s unable to perform basic life skills; he appears to lack any long-term memory and fixates on particular interests, such as rabbits and more generally, soft things. This particular fixation, plus Lennie’s unawareness of his strength, has led him to unintentionally crush mice to death on several occasions.

According to George, Lennie is dead weight or what TV Tropes calls “The Load.” George only tolerates Lennie because he promised the latter’s Aunt Clara to look after him when she died. He often reminds Lennie of how helpless he is without him–“How’d you eat? You ain’t got sense enough to find nothin’ to eat,” he says as early as the first chapter (Steinbeck 13). Clare Lawrence notes George also gives Lennie no agency. Any time Lennie “attempts to ‘do his own thing,’…George retakes control. Lennie is completely subordinated to George” (Lawrence). Because readers see George providing Lennie with basic care, or scolding him for doing things like carrying around dead mice, they are primed to sympathize with abled George over disabled Lennie. Worse, because Lennie has never had agency, and since George takes physical care of him, he sees George as a friend and ally. Never mind that George can be physically and verbally abusive to Lennie, slapping him and calling him names like “son-of-a-bitch” (Lawrence).

But Lennie is still a person, yes? He has specialized interests, such as animals, and he shows a desire to help George work and farm, thus involving himself in a non-disabled, neurotypical world with abled peers. Actually though, according to Clare Lawrence and other scholars, these traits aren’t enough to make Lennie human. Lawrence notes Lennie is described as “other” or “non-human” from Of Mice and Men’s first pages. Steinbeck characterizes Lennie as “dragging his feet…the way a bear drags its paws” and “shapeless,” as in, without human form (Steinbeck 2).

Disabled Characters as Non-Persons

Lawrence notes that although all Of Mice and Men’s characters are “animalistic” to an extent, eking out their existence in a harsh world, Lennie is more animal than the others (Lawrence). She highlights the fact that while characters like George, Slim, and Candy are expected to care for animals as part of farm life, “Lennie is not given sufficient human status to be able to care for animals lesser than him” (Lawrence). Lennie does try to care for animals, such as when he is given a puppy. But because he has never been educated meaningfully, or given agency, Lennie only knows to pet and manhandle said puppy. At one point, Lennie smacks and kills the puppy, perhaps as discipline for perceived misbehavior. No one considers Lennie may have done this because of how George treats him–calling him a “good boy” when he pleases George, and abusing him when he doesn’t. Instead, Lennie’s killing the puppy is more evidence of him being “barely contained” and in need of “segregation from society” because giving him freedom and agency of any kind ends in disaster (Lawrence).

Lennie, then, is an ultimate object of pity in most readers’ and viewers’ minds. Yet Steinbeck is not content to leave Lennie as a pity object. In fact, because Lennie spends most of the novel “barely contained,” Steinbeck takes every opportunity to characterize him as a “monster” (Lawrence). Granted, this is usually in the context of Lennie not knowing his own strength, as with the dead mice and dead puppy. Sometimes though, it’s in the context of Lennie attacking someone because he thought George was being hurt, or touching and fondling a woman because she had a pretty dress or soft hair. In these situations, Lennie is assumed to be violent, a sexual deviant, or both. Again, the abled majority does not consider any other motives for Lennie’s behavior. In fact, just before the novel’s outset, he was nearly lynched for touching a woman and fondling her red dress. As Clare Lawrence notes, Steinbeck uses these incidents not to point to ableism or incite sympathy for Lennie, but to “other” him further. According to Lawrence, Steinbeck’s “othering” points back to the eugenics philosophy, embraced by proponents like Dr. Peter Singer, that intellectually disabled people are more animal than human.

If Lennie is more animal than human, and if he has engaged in dangerous behavior, it follows that according to eugenics–and Steinbeck–Lennie is a dangerous animal. Dangerous animals must be contained, and put down if containment isn’t possible. George follows this logic to its conclusion after Lennie is accused of raping and murdering the wife of Curley, an antagonistic and abusive ranch hand. In reality, Lennie didn’t rape Curley’s wife; she actually let him stroke her hair and face, fondle her, and embrace her. But Lennie, still unaware of his own strength, ended up accidentally breaking her neck. However, no one defends Lennie, except to point back to his intellectual disability as a weak excuse for what he did. Using soothing tales of the rabbits Lennie wants to tend, George takes Lennie off into the woods and shoots him in the head, point blank.

Defending Lennie’s Demise

Lennie’s killing remains controversial among Of Mice and Men readers today, almost a century after its first publication. Clare Lawrence writes that in many discussions, the central question is not whether Lennie’s death was murder or whether there were alternatives to his murder. The question, rather, is “to what extent George…was justified” (Lawrence). Even in 2021, reader and viewer sympathy remains with George over Lennie. Mercy killing is still seen as a better option than trying to understand Lennie and relate to him as a human.

The reasons are simple and familiar. The majority of the novel’s audience is not disabled; Lennie’s disabilities were severe; the era in which the characters live had no concept of disability rights, let alone inclusion. Laws like the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) and Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) did not exist; the most common fate for someone like Lennie was institutionalization. Some scholars also point out that according to Steinbeck, Lennie was based on a real person, a mental institution inmate he met once (Nobelprize.org).

Whatever the reasons for Lennie’s death, the truth remains. At Of Mice and Men’s end, we have a dead body, one that belonged to a human who had disabilities. Lennie had little to no chance of a future outside of George, with whom he probably trauma bonded more than anything. Clare Lawrence points out Lennie also had no real hopes and dreams; even his dream of tending rabbits wouldn’t have panned out had he lived, because he would’ve killed the animals (Lawrence). Lennie then, becomes a perfect example of how not to handle death in the context of disability. He dies without choice, without agency, without the simplest acknowledgment of humanity. The fact that his murder is considered justifiable in any context indicates the conversation about disability and death is far from over.

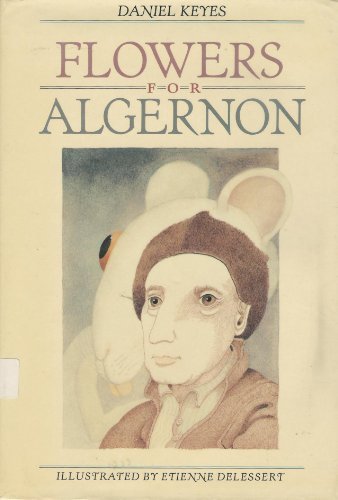

Flowers for Algernon

First published in 1959, Daniel Keyes’ Flowers for Algernon was one of the first novels after Of Mice and Men to feature a protagonist with a disability. It came onto the literary scene during a time of “awakening” for people with disabilities and their families (mn.gov). According to the mn.gov project “Parallels in Time: A History of Developmental Disabilities,” 1959 was smack in the middle of “The Parents’ Movement,” wherein parents “demanded [better] services for their sons and daughters,” because of the “poor living conditions” in institutions. However, The Parents’ Movement and subsequent “awakening” were not yet inclusive. They did not yet fully acknowledge people with disabilities as people. In fact, efforts of The Parents’ Movement were encapsulated under the slogan “The Retarded Can Be Helped” (mn.gov). Most of the efforts were focused on improving the lives of “the mentally retarded,” who were overwhelmingly institutionalized, often from birth.

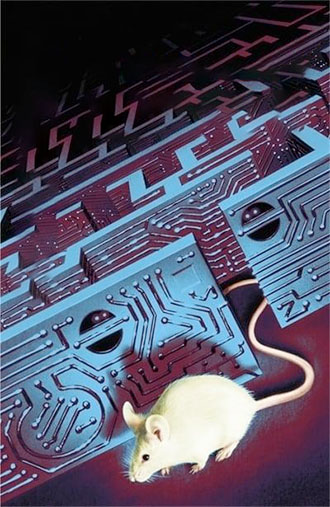

Daniel Keyes’ novel reflects this attitude in the characters of Charlie Gordon and Algernon. Algernon is a lab mouse undergoing scientific experiments to increase his intelligence. Charlie is a student and resident at The Beekman College Center for Retarded Adults. Note this is not a college; it is an institution that attempts to educate disabled adults to the extent the able-bodied staff feels they can be. Charlie, for instance, has an IQ of 68, over 30 points below average, and works with staffer Alice mostly on basic literacy. Charlie works as a janitor at Donner’s Bakery, where his coworkers bully or ignore him, and his supervisor makes clear Charlie’s job is given out of charity. Charlie is in his thirties, but does not act as an adult in any way, nor is he given any agency over any decisions.

In fact, it is Alice Kinnian, Charlie’s social worker, who decides when his life will change. She recommends Charlie as a candidate for Dr. Strauss and Professor Neumer’s intelligence-increasing procedure. Strauss and Neumer take Charlie on, subjecting him to several tests before the actual surgery. One such test pits Charlie against Algernon in solving a maze. Algernon, who has already undergone the intelligence-increasing procedure, has at least triple Charlie’s IQ and initially beats him at every maze. Algernon and the mazes become a microcosm for Charlie’s journey, as the latter learns more about the world, himself, and his place in it. To wit, Charlie undergoes Strauss and Neumer’s operation, and in a short period, his IQ triples, from 68 to around 210, the genius range. However, increased intelligence does not mean Charlie is treated as an intelligent, or even fully capable and functioning, person.

Charlie’s Dubious Cure

Readers are meant to root for Charlie as he explores everything from art, politics, and religion to romance and sex. The “progress reports” that make up his story show Charlie going from barely literate to mastering grammar and punctuation quite literally overnight. Charlie gets two promotions at work, plus associated raises, and begins living independently in a New York City apartment. He admits his attraction to Alice and takes her to the movies, somewhat as a romantic experiment. But despite all this, Strauss and Neumer view Charlie more as an animal who has overcome the “instincts” of intellectual disability than a person. At one point, Charlie discovers a bakery coworker named Gimpy has been stealing and undercharging employees for kickbacks. When Charlie asks Strauss and Neumer if he should confront Gimpy or tell Mr. Donner, they discourage him. Neumer tells Charlie he was “an inanimate object” during most of Gimpy’s crimes, making him unaccountable for saying anything. Whether Charlie was accountable in any sense, the fact that Neumer sees him as a now-animated “object” is at best disturbing and at worst blatant dehumanization.

Other characters in Flowers for Algernon don’t treat Charlie any better after his operation. Formerly, Charlie’s coworkers taunted him daily, set him up as the butt of jokes, and made his name a byword (making a mistake = “pulling a Charlie Gordon”). But now that Charlie has had his operation, his coworkers are upset at his intelligence and pressure Mr. Donner into firing him. Alice tries to reciprocate Charlie’s affection, but her attempted kiss triggers traumatic memories for him. While both decide they cannot continue in a relationship, Alice behaves as if the burden is on Charlie for experiencing trauma. Charlie makes a new friend named Fay, but she rejects him on the grounds that his apartment is too neat and he is too intelligent for her. Charlie finds a newspaper report that says his sister Norma believes he is a resident at the Warren State Home for intellectually disabled adults, and that essentially, his family has long since moved on as if he did not exist.

Essentially then, Charlie has no place in the world either as a genius or an intellectually disabled person. This, plus his slowly decreasing intelligence, contribute to Charlie’s new, cold-hearted nature. Said nature is on full display when he visits the Warren State Home, knowing he will end up there for the rest of his life and hoping to find some camaraderie there. Instead, he notes the blank and hopeless faces of the residents, and notes he is nothing like them, nor does he wish to be.

Professor Neumer mentions this contrast when he brings up who Charlie used to be versus who he has become. As a person with an intellectual disability, Neumer says, Charlie was open and warm-hearted, but intelligence has made him arrogant and self-absorbed. Even when Charlie points out Neumer’s arrogance, it’s treated as an afterthought. Readers are meant to think Charlie was “better” with intellectual disability, which seems to indicate he is better off with a disabled identity (as opposed to Tiny Tim, Colin Craven, and Pollyanna Whittier). But that line of thinking is flawed on three counts. One, the implication is, intelligence made Charlie arrogant when it doesn’t necessarily do so for abled people. Yes, Neumer and Strauss are arrogant, but Keyes implies their arrogance only happened after long-term exposure to the scientific world, which an intellectually disabled person wouldn’t have. Two, Keyes implies that not only intelligence, but experience and the ability to make his own judgments, made Charlie an unpleasant person. In other words, intellectually disabled people can’t handle self-determination because they will misuse it.

This theory persists among disability experts today. Real adults with Down Syndrome, learning disabilities, some forms of autism, or other intellectual disabilities are commonly placed on rigid plans and schedules, even in their own homes. In minute detail, these plans explain things like when these people can get up or go to bed, when and what they’re expected to eat, how often and how much they may spend money, and how they will spend leisure time. Caregivers, usually from outside agencies, carefully monitor such plans so the individual with a disability will use time wisely or not get “out of control,” whatever that means in the caregiver’s estimation.

The third and final way in which this thinking is flawed goes back to how Neumer and Strauss, like most other abled people, treat Charlie. Neumer and Strauss see Charlie as a non-person, whether he’s intellectually disabled or a genius. What Charlie absorbs then, is that highly intelligent people naturally treat others as non-persons. They are naturally arrogant and selfish, serving the brain at the expense of the heart. This progression exposes another key flaw in Neumer, Strauss, and people like them, who use intelligence as weapons against people like Charlie. That is, people like Neumer and Strauss persist in the belief that disabled people, particularly the intellectually disabled, can only mimic simple behaviors (“monkey see, monkey do.”) Thus, they blame disabled people when they mimic “non-typical” behavior or “act disabled” (or the phrase’s variants, such as “act autistic.”) What these abled, “intellectually superior” people forget, however, is that if they are being mimicked, they are the ones providing negative examples. They are the ones engaging in “bad behavior.” Arrogance, selfishness, rudeness, or any other negative behaviors are treated as disability issues alone, when they are truly issues of all human behavior.

Daniel Keyes fails to address this possibility, though. As a genius, Charlie is almost vilified, his new negative characteristics played up to a ridiculous point. This causes the reader to lose sympathy for Charlie, and to believe he’s better off as a “retard” because “retards” allegedly can’t process complex emotions or ideas. That’s unfortunate, but at least their lack of complexity means people like Charlie can’t offend or hurt anybody. At this point, the reader probably doesn’t want Charlie to die. After all, nobody ever got a death penalty for being a jerk or a snob. But having observed his intelligence combined with arrogance, the reader might want Charlie’s “new self” to die. In other words, Charlie makes the reader more comfortable, less offended, if his abilities “die” for the sake of reversion to what abled people think of as a “good” person.

When the “Cure” Wears Off

What then, is left for Charlie Gordon? According to Daniel Keyes, the only answer is institutionalization and eventual death. Charlie himself does not die in the novel, but Algernon does, after losing all his intelligence. As before, Algernon serves as a microcosm for Charlie, who has regressed back to an IQ of 68 and moved permanently into the Warren State Home. He will eventually die there and has concluded death is the only sensible possibility for him. Charlie’s last words to the reader aren’t for himself. Instead, he asks whoever reads his progress reports to place flowers on Algernon’s grave. The request hearkens back to the warm-hearted Charlie that Neumer and others professed to prefer, and the implication of Charlie’s death might imply some peace for our protagonist.

In reality, Algernon’s death and Charlie’s eventual one raises a lot of red flags for readers. The deaths smack of ableism and call into question not only Daniel Keyes’ intentions in writing Flowers for Algernon, but how people with disabilities are treated in real life. Specifically, Charlie spends the novel on two opposite ends of the intelligence spectrum. He is accepted on neither, which readers could chalk up to the fact, both ends of the spectrum are so extreme. But extremity aside, Charlie reads as a character who is only accepted insofar as others let him be. Like Lennie, he is given no agency and no humanity. Charlie is not treated quite as much like an animal as Lennie was, but readers understand this is because he showed high intelligence throughout some of the novel. Had he not, he would’ve been treated much like Algernon, except with a larger, biped body. Additionally, Charlie only gains humanity through intelligence that Alice, Neumer, and Strauss give to him. This construct implies intellectually disabled people can only participate in life until the charity of the able-bodied runs out. At that point, they can either “sink or swim”–live life on the able-bodied majority’s terms, or regress and die.

Charlie’s journey also raises red flags in regard to its real-life context. Recall, Flowers for Algernon was written during The Parents’ Movement, where disability rights were focused mostly on non-disabled parents or caregivers. Using their lenses of disability, these parents and caregivers gave their loved ones labels like “The Retarded.” The parents and caregivers, not disabled people themselves, fought to convince the wider world “The Retarded” deserved better than isolation, abuse, and squalor.

Of course, Charlie Gordon doesn’t experience institutional abuse. We must also remember, there is no such thing as politically correct history, meaning real people shouldn’t be judged for information or morals they did not have. Yet we can and should judge Flowers for Algernon for what it represents. The novel is in fact a story of a “retarded” man getting help. But Charlie is only “helped” when he becomes part of the abled majority. Once he loses the abilities he gained, he returns to the status quo of “retarded.” Charlie’s best hope still lies with “his own kind”–intellectually disabled people, and them alone. He will no longer be able to read or write effectively, learn or understand, or participate in reciprocal relationships. Daniel Keyes implies this is the fate of all people like Charlie. They may be cared for. They may even be loved. But their lives remain so small and yes, so animal-like, that the deaths of such people are their best outcome.

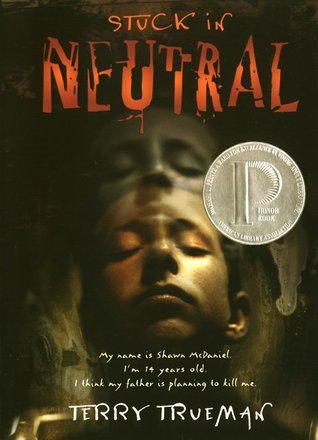

Stuck in Neutral

Author Terry Trueman’s Stuck in Neutral is a young adult (YA) novel first published in 2000 and reprinted in 2012. It is unique among the other works we’ve discussed because of its publication and reprint dates, and the way it has been received since then. Stuck in Neutral was first published ten years after the Americans With Disabilities Act (ADA) was signed into law, and 25 years after the birth of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). The novel’s 2012 reprint came at the beginnings of a movement toward full inclusion of people with disabilities in society. Stuck in Neutral, however, does not promote inclusion or acceptance of PWDs, even in our contemporary time period. It does not promote the rights, education, or human needs (as opposed to “special needs”) of PWDs. If anything, Trueman’s book presents the exact opposite, making it rather “stuck.”

The protagonist of Trueman’s novel is 14-year-old Shawn McDaniel. He has an eidetic, or photographic, memory and lives with severe cerebral palsy (CP). The latter is the focus of the book, Shawn’s life, and how others relate to Shawn. As our protagonist puts it, he can tell you anything you want to know about say, George Washington, from his wooden teeth to his relationship with Thomas Jefferson. But actually ask Shawn about “the old dead first prez,” and you won’t get any of that information. All Shawn can do is “sit there and drool, if my drool function is running…or whiz my pants…or go ‘ahhhh’ if my voice…hasn’t kicked in” (Trueman 4). Therefore, Shawn’s family, teachers, and everyone else around him think he’s “dumb as a rock,” and Shawn can’t do anything to convince them otherwise (Trueman 5).

Shawn describes undergoing yearly IQ tests so his educators can determine what goes in his Individualized Education Plan (IEP). Shawn describes questions like, “What’s 2 + 2” and of course, “Who was George Washington?” He also mentions being asked to match pegs or colored shapes to proper holes. Shawn knows every answer, but can’t verbalize any, and can only throw or drop the pegs and blocks. His IQ has been estimated at 1.2, or a mental age of 3-4 months. Combined with his inability to communicate, this means Shawn remains uneducated, unexpected and unable to do anything of value.

The premise of Stuck in Neutral is discouragingly faulty for a contemporary novel about a person with CP (or any disability). As Shawn reminds readers, there are ways for PWDs in his era to communicate. He snarks about some of them, mentioning somebody could’ve put his hand over a Ouija board and let him choose letters. Yet a lot of the communication alternatives he mentions, such as use of computers or picture boards, are available in real life. By 2000, some had been available for at least a few years, even if in their roughest forms. The implication then, is not so much that Shawn can’t communicate or learn to use technology. It’s that Shawn is not allowed to do these things, presumably because of an abysmally low IQ estimation. One could make the argument that Terry Trueman doesn’t believe PWDs should be allowed to do these things unless they can communicate the “normal” way, which would explain Trueman placing Shawn in this position.

Disability and Self-Hatred

Trueman’s novel is not just problematic in how it presents Shawn. It’s also a huge step backward in disability representation because of how Shawn presents himself and thinks about his life. Throughout the book, Shawn calls himself “retard” or “retarded,” a word that was considered offensive in 2012 and is now widely regarded as an ableist slur on a par with the N word. Shawn embraces the idea he is stupid and incapable, and inferior to other people, such as siblings Paul and Cindy. He makes negative comparisons between himself and Paul, a star athlete, and describes Cindy as “Special Education Teacher of the Year” for teaching him to read while he “sat there looking retarded” (Trueman 4). Throughout the book, Shawn talks about strengths like his memory, but tends to do this in conjunction with what he can’t or won’t do. Thus, readers are more apt to see Shawn as a bitter victim rather than an intelligent, understandably snarky disabled person who is coping as best he can with an ableist environment.

The biggest problem with Stuck in Neutral, though, is that its whole plot centers on euthanasia. We find out Shawn’s father Sydney is a Pulitzer Prize-winning author who got the honor for a poem about Shawn, implying he used his son as a form of inspiration porn or pity. Sydney left his family shortly after writing the poem, ostensibly because of Shawn’s cerebral palsy. Worse than that, Sydney has appeared on a talk show without Shawn, discussing how difficult his family’s life is. He appeared on the same episode as Earl, a father who chose to euthanize his disabled son after concluding the son was suffering. When Sydney is asked if he would follow Earl’s example, his answer is vague, perhaps intentionally so. Sydney assumes Shawn does not know or understand his appearance on the talk show or his use of Shawn to get awards and attention. He also assumes Shawn is suffering, with no hope of any change or a true future.

Shawn spends the rest of the book speculating about and fearing Sydney’s intention to kill him. He doesn’t fight against the possibility because again, he can’t. In fact, despite his fear, Shawn seems somewhat at peace with the euthanasia idea. Shawn claims whatever Sydney does, he’ll “soar” as a result. Shawn and his family don’t discuss any beliefs about the afterlife, so it’s unclear whether Shawn’s referring to Heaven. However, his verb choice implies the idea of physical freedom. Communication-related and emotional freedoms are similarly implied. In other words, whether or not he wants or chooses euthanasia, it is Shawn’s only hope. Trueman actually takes this idea a step further than Steinbeck or Keyes did, because Trueman doesn’t just imply Shawn’s life is worthless. Trueman implies Shawn’s very existence is worthless, and that since said existence can’t be changed, euthanasia is the closest thing his family has to a solution.

Continued Defense of Disabled Death

Interestingly, readers never learn if Shawn is euthanized or not. He’s given an ambiguous ending that almost requires readers to speculate–and argue about the value of his life. However, the events leading up to the ending are more than a bit suspicious. Shawn is left alone with a caregiver while the rest of the family goes on a trip; it’s implied this occurs often. Sydney comes over while Shawn is sleeping, and…the novel ends. Coupled with Sydney’s poem and appearance on the talk show, plus other small incidents like asking an annoying crow if it wants “a piece” of Shawn, euthanasia seems almost a given. The fact that the decision isn’t made is actually another strike against Trueman. The events read as if the ending were left intentionally ambiguous so if controversy ever arose, Trueman could honestly say Shawn lived, giving himself an “out.”

Controversy did arise–one recorded incident. The Wikipedia article on Stuck in Neutral reports some parents protested the book when it was assigned to their kids’ classrooms. However, the protest had nothing to do with euthanasia. Rather, the parents complained about the “sad and violent” subject matter, making Stuck in Neutral just another in a long line of contested books that faced the same complaints. The article goes on to state Stuck in Neutral is often required reading, not just in classrooms, but in special education classrooms. In other words, students with disabilities, who are already set apart in negative ways, are required to read a book about a boy who faces euthanasia and can do nothing to stop it. Like Me Before You, Stuck in Neutral becomes a disability snuff novel, aimed at a disturbingly young and impressionable audience.

Emotional or Mental Death

Despite the continued presence and praising of novels like Stuck in Neutral, authors are trying to change the trajectory of disabled characters. If anything, articles on sites like The Mighty and Literary Hub frequently urge writers to avoid scenarios in which a disabled character dies only because of disability. Writers also urge each other to avoid this trope, as well as companion tropes like the healing of a character with a disability (Disability Writing). Yet, some less obvious “death tropes” still exist within disability representation. These often occur when a disabled character faces emotional or mental death rather than physical death.

For the purpose of our discussion, emotional death is a form of grief, but not simply the emotion of grief. A character experiences emotional death when failing to meet their external and internal goals means their life will have a permanent negative trajectory. The character will stay alive, but will experience a lesser life. Furthermore, they may never withstand the grief and trauma that came with failing to reach their goals.

Plenty of characters without disabilities experience emotional death, with or without the threat or outcome of physical death. Emotional deaths are some of the ones we as readers most often remember, because they’re so poignant and relatable. We find the threat of emotional death in The Odyssey‘s Odysseus, who may never get home to Ithaca and his family, or if he does, may find his wife and son have left him. We find it in Romeo and Juliet, where the title couple commits suicide because they despair of ever being together. Emotional death occurs throughout today’s popular YA series, from Harry Potter to The Hunger Games, as heroes like Harry and Katniss fight to preserve not only their physical worlds, but the safety, love, and hope therein.

Emotional or mental death then, is probably the most accessible type for characters with disabilities. Simply by allowing them to live, writers who put CWDs at this risk are acknowledging, disabled people have a wide range of experiences, emotions, opinions, and goals. Additionally, focusing on emotional death rather than physical removes the implication that PWDs are better off dead. After all, if they were better off dead, they would not exist to tell the story at hand. Even better, placing a disabled character at risk of mental or emotional death almost forces their creator to examine the true disabled perspective. Risk of emotional death implies the character understands the wider world, how their actions affect others, and high stakes, all of which disabled people are commonly not expected to understand.

All that said, emotional death has a few booby traps for CWDs, too. Some of these are equally as problematic as the pitfalls we’ve discussed. Others are less so, but may read as stale if poorly handled. Additionally, the concept of emotional death must be handled with more care if physical death is also a factor, such as in a murder mystery, military saga, or dystopian story. Most contemporary novels featuring CWDs deal with this in some measure, and some are written better than others.

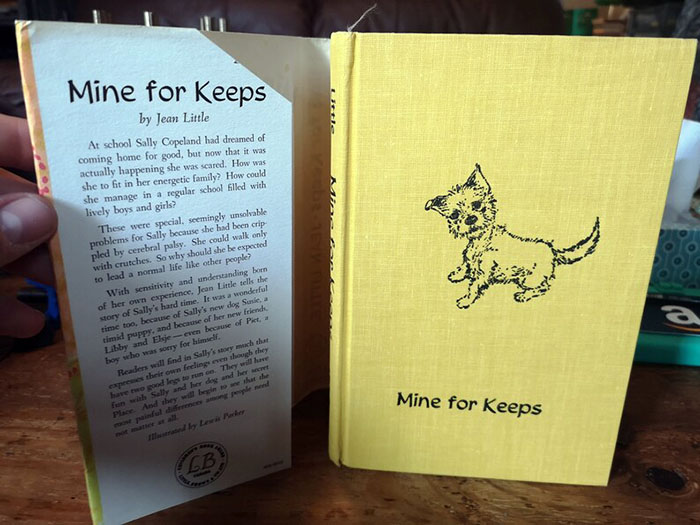

Mine for Keeps

Originally published in 1962, Jean Little’s Mine for Keeps was revolutionary for its day. The children’s novel stars fifth-grader Sarah Jane (Sally or Sal) Copeland, who lives with cerebral palsy (CP). Sal lives in an unspecified Canadian province and, up to the story’s events, has lived full-time at Allendale, a school for children with disabilities. Not much is known about Allendale, but it’s assumed to be an actual school where students are educated academically, on a level with abled peers as much as possible. Life skills are a big part of the curriculum. Sal notes several of her classmates also have CP, and like her, they receive physical and occupational therapy, as well as different levels of help with basic tasks.

However, Sal herself is more capable than almost any of the protagonists we’ve discussed, especially for a book written in 1962. Sal learns and communicates at an expected age level, and although she cannot do fine-motor tasks like buttoning buttons, she does not struggle with basic self-care, nor the understanding of why self-care is necessary. She recognizes her differences, but resists being babied or underestimated. And while Sal acknowledges disability is difficult, she doesn’t have a constantly bitter attitude. When she does get angry or upset, it’s chalked up to her having a hard time, not necessarily because of CP.

Jean Little’s plot is ahead of its time, in that unlike her contemporaries, Sal Copeland doesn’t stay in a disabled-only environment. When we first meet her, she’s coming home from Allendale for good, a “wish come true” she has had for years (Little 1). Little explains Sal’s family has campaigned hard for inclusion and mainstreaming in their town, as well as for a therapy center to be built near their home. Now that the center is operational, Sal can receive needed services without the need for separation from her family or segregation from community life. Sal’s parents and teachers are rooting for her to become as independent as possible, and Allendale’s headmistress has sent Mom and Dad a long letter explaining how they can all make that happen. For instance, the headmistress suggests Sal should wear clothes without fasteners except for large easy ones, since her fingers won’t let her keep hold of buttons and zippers. She also suggests Sal wear a feminine but short haircut, since hairstyling is another fine-motor task. The implication is that while Sal should continue attending therapy and improving life skills, her mastery or lack of those skills should not determine whether or not she can participate in a majority-abled world. Again, Little’s treatment of these issues would’ve been almost unheard of in an era when most disabled people still lived in institutions. To some extent, after many reprints of Mine for Keeps, the idea that a disabled person’s life should focus on more than basic skills remains revolutionary.

It might seem odd, then, to think of Sal Copeland as in danger of emotional death. Mom and Dad have made clear she’s home to stay. Sal asks to go back to Allendale when her new life overwhelms her and is gently but firmly told “no.” Thus, institutionalization, the “death” other disabled protagonists like Charlie Gordon faced, is off the table. Even segregated education is off the table. When Sal struggles to complete a mental math test on her first day in a general ed classroom, her teacher doesn’t shame her. Rather, he admits he should’ve recalled that, because Sal’s writing speed is erratic, she might need extra time. The teacher, Mr. Mackenzie, does everything in his power to accommodate Sal in an era before IDEA and IEPs. He shows compassion without pity, and listens to how his student feels about going from a life where everyone she met was like her, to one where almost no one is. Those who have power over Sal are firmly on her side and determined to help her live on all fronts, as the disabled person she is, not a normalized version.

Social Risk and Possible Death

Like kids of all abilities, Sal struggles the most with socialization. The first classmate she meets, Libby, goes out of her way to be nice to Sal, telling her what she needs to know about school, giving her the desk next to Libby’s, and bringing her a library book to read at free period. As the book goes on though, Libby’s enthusiasm for life makes her forget Sal’s CP at times. Thus, Libby looks like she’s pitying Sal or engaging in abled privilege, and the girls clash. At one point, Sal worries she has permanently lost Libby as a friend, a kind of emotional death because until Libby, she had no real friends of her own. (Little implies Sal’s classmates at Allendale were more like warm acquaintances, perhaps because everyone there was so focused on coping with disability).

Sal faces a deeper and riskier emotional arc with a classmate named Elsje and her brother Pieter (Piet). Elsje is a Dutch national student who came to Sal’s school the year before, and who was Libby’s “best friend” first. Out of jealousy and fear, Elsje acts cold to Sal from the moment they meet. She observes Sal dashing down answers while Mr. Mackenzie goes over them after the mental math test, and assumes Sal cheated on purpose. She tends to treat Sal as weaker and more childlike than a typical fifth-grader, such as when Sal witnesses a boy named Luke taunting someone named Piet who it seems might be disabled, too. Sal tries to ask Elsje about Piet, but Elsje assumes she’s upset about Luke’s actions. “Do not worry about him,” she comforts, ready to move on.

Elsje is not a direct threat to Sal’s social independence. That is, she’s not powerful enough to ensure Sal is ostracized if the other girl somehow displeases Elsje or Libby. But Sal recognizes that something, perhaps disability-related, is holding Elsje back from involving herself socially with Sal and now to a degree, Libby. Sal’s unspoken fear is, if Elsje has to retreat from her, Libby will, too. Thus, Sal will lose the friendship of both girls, plus the friendships of a couple other students she’s developing. When Sal learns Elsje’s full story–she’s Piet’s little sister, and Piet has a heart condition–fear grips her harder. Piet, like Sal, is “different.” Sal has learned that people who are different don’t always get to participate. They get babied or bullied, or told that their need for accommodation shouldn’t matter if they’re really equal people. If Elsje, the “leader” of Sal’s friend group, retreats from her, she will communicate, “You are like Piet. Piet is enough trouble. I don’t need you, too.” Sal will be alone again, without any friends that are “hers for keeps.” She may still have friends, but only in the sense her friendship is convenient for the abled majority.

One Step Forward, Two Steps Back

Sal gets a chance to meet Piet, and her struggle intensifies. Jean Little falls into a booby trap with Piet’s character, in that like Colin Craven, he is considered an “invalid” and has a bitter, nasty attitude. To his credit, Piet isn’t as spoiled or vocally self-pitying as Colin. But he is quick to point out what he cannot do, and accuse people like Elsje of mocking him if they suggest he can change his situation. Meanwhile, Elsje skirts the line of acting like Piet’s legitimate heart condition is all in his head. But to Jean Little’s credit, she focuses more on Sal’s emotional development once Piet comes into the story. Some of her treatment is a bit hokey; Sal realizes Piet has it much worse than her, and becomes determined to be more independent. At the same time, Little makes Sal the center of a plan to help Piet and Elsje enjoy life and a true sibling relationship.

Along with the new humans in her life, Sal has a new animal friend, a shy Westie terrier named Susie. It’s tradition for all the Copeland children to have their own pets, so getting Susie says something not only about Sal’s independence, but the expectation that she, like her siblings, will participate in a rite of passage. Indeed, CP or not, Sal becomes Susie’s sole caretaker. For instance, with Dad’s help, Sal engineers a wheeled cart so she can feed Susie without bending down to place her food and water bowls, thus getting off-balance. Sal also learns how to safely hoist Susie onto her bed at night, and help Susie with the anxiety that accompanies her natural shy temperament. These skills in interdependence eventually serve Sal well with humans, especially Piet and Elsje.

Elsje is pretty close-mouthed with Sal and Libby when it comes to what day-to-day life with her bitter brother is like. But one day, she lets it slip that Wilhelm, the dog who was supposed to be Piet’s, follows her around and obeys her, not because he loves her. Rather, Piet refuses to spend time with Wilhelm, and Elsje is the only one able or willing to give him attention. Elsje has begun training Wilhelm in order to stretch the dog’s brain, give herself an outlet, and show Piet what dog ownership could be like. Sal agrees bonding with Wilhelm would be great for Piet and mentions she’d love to train Susie. However, Sal doesn’t have the experience Susie needs, and her parents and siblings are too busy with their own lives and pets to provide support. When Libby mentions the untrained behavior and obesity of her dog Chum, Elsje has an idea for Pooch Academy. She, Sal, Libby, their dogs, and a couple other kids will meet weekly so Elsje can teach them all proper dog-training skills.

Subtle Inspiration Porn?

Piet does not “come around” to Sal and her friends’ way of thinking if what that means is, he develops an optimistic, ever-cheerful outlook and “overcomes” his heart condition. However, Piet does begin expressing curiosity about Pooch Academy, particularly Elsje’s role in it, since she has been so narrowly focused on him and her family since they moved to Canada from The Netherlands. Encouraged, Sal and her friends begin planning a big presentation to surprise Piet with how much they’ve learned–and how easy it will be for him to add to Wilhelm’s knowledge. Unfortunately, Elsje comes down with the flu before the presentation. The kids learn she’ll likely be ill longer than normal. Why isn’t specified, although readers could infer she and Piet both have fragile health. Failing that, one could infer Elsje’s parents didn’t have access to the healthcare they needed in their home country, making it harder for their children’s immune systems to adjust to Canada.

Sal and friends confer, and determine they must do something special for Elsje, as Christmas is coming and she will be sick for the holiday. Plus, as Sal points out, Elsje was the one who held Pooch Academy together and had the expert knowledge the other kids needed. When she learns December 6 is St. Nicholas Day in The Netherlands, Sally comes up with a plan for an extravagant gift for Elsje. She, her friends, and their parents chip in to get Elsje her own puppy, whom she names Nicholas–Nicky–after the day and the friendships she treasures. The story ends with Sal ruminating that although Elsje got the puppy and the physical gifts of the night, it is she who finally has something that is “hers for keeps”–an independent and interdependent life. She has conquered emotional death, finding her life fuller than it has ever been.

Sal does strike a good balance between dealing with typical fifth-grader problems and disability-specific ones, such as transitioning from boarding school to mainstream school and family guest to full-time family member. Her cerebral palsy makes an appearance when it needs to, such as when she gets used to her new clothes and haircut or goes to an orthopedist for an annual checkup. The disability is not intrusive. Sal herself is also not the target of full-on inspiration porn, nor is she expected to “throw off” disability whenever abled people want her to. In many ways, Sal Copeland is the most fully realized disabled protagonist we have discussed, and her emotional death is presented as legitimately dangerous, but not melodramatic.

However, Mine for Keeps is not perfect when it comes to placing Sal in an emotional death situation. As blogger Crippled Scholar notes, much of Sal’s plot revolves around “[saving] the esteem of a bully so his sister will be happy” (crippledscholar.com). Crippled Scholar points out that Sally’s focus on keeping Elsje happy actually makes Mine for Keeps less about her journey, and more about how she can please abled people. Additionally, Crippled Scholar writes that because Sally pressures Piet to perform with Wilhelm in front of an audience, she’s actually succumbing to peer pressure from Elsje and friends. That is, they’re counting on her to “save Piet,” in much the same way Tiny Tim “saved” Scrooge or Mary “saved” Colin (crippledscholar.com). The only difference is, Sal uses her able-bodied peers to save Piet, not her disability or disabled identity. In so doing, Sal participates in lateral ableism, where a disabled person looks down on a group member because their disability or attitude is perceived as “worse.”

If we focus entirely on Sal, the emotional arc doesn’t redeem itself, either. That is, Sal is accepted by the abled majority only to the extent she can help someone else, namely her “moody” friend, stay happy (crippledscholar.com). As with the other novels we’ve discussed, the well-being of the abled community is paramount. If a disabled person has to be physically or in this case emotionally sacrificed, so be it. It’s better if, like Sal, the disabled person doesn’t realize how they’re being sacrificed, or agrees to it as Sal does with Elsje. One could argue Jean Little was simply trying to impart lessons about friendship, namely that children with disabilities can have friends too and facilitate their happiness in non-inspirational ways. Yet as Crippled Scholar puts it, these lessons cross into “smarmy morality” and make Sal secondary in her own story. Sal lives and thrives physically and emotionally, and yet, in some form, it feels as if her author killed her.

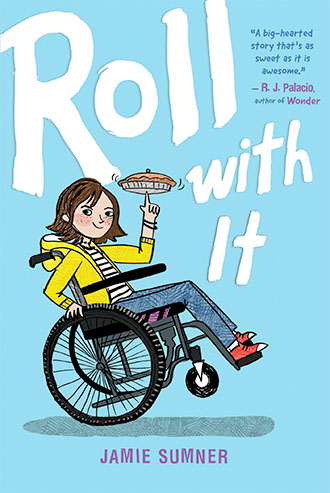

Roll With It

Published in 2019, Jamie Sumner’s middle grade (MG) novel is one of several coming out of the recent move toward representation and inclusion. Its protagonist is Ellie, another girl with cerebral palsy. Ellie’s cerebral palsy is better drawn than Shawn McDaniel’s or Sal Copeland’s though, because of its context and crafting. That is, it makes sense for Ellie to have CP because of how common we now know the condition is. The CDC calls it the most common motor disability in children (a bit of a misnomer since CP is lifelong). Additionally, Ellie is presented as living in the majority-abled world; she has never been in an institution, group or care home, or school for disabilities like Sal Copeland’s Allendale. The context of Roll With It communicates, for better or worse, disabled people are expected to live in the world.

Disabled and Dynamic