Double Indemnity: An In-Depth Look At A Film Noir Classic

‘It has all the characteristics of the classic forties film as I respond to it. It’s in black and white, it has fast badinage, it’s very witty, a story from the classic age. It has Edward G. Robinson, and Barbara Stanwyck and Fred MacMurray and the tough voice-over. It has brilliantly written dialogue, and the perfect score.’ Woody Allen

In many ways, Woody Allen’s quote encompasses all the main elements that make Billy Wilder’s Double Indemnity (Paramount Pictures, USA, 1944) a masterpiece. Anchored in the film noir’s aestheticism, its low-key lighting, oppressive music, sharp dialogues and breathtaking performances achieve to make this film an unavoidable classic.

It is essential to understand the characteristics of film noir’s aesthetic to appreciate Double Indemnity‘s richness. The term has first been used in 1946 by French critics to describe the rise of crime dramas in Hollywood that explored sexual motivations and growing cynicism. Its low-key black and white style is significantly recognizable, influenced by German expressionism and 1930s’ gangster movies. In a good film noir, we expect to encounter feverish desire and transgression, portrayed by sympathetic anti-heroes who remain outside society, in an underworld of misdeeds.

Double Indemnity adopts film noir’s and crime fiction’s properties, and responds to these anticipations. The plot is based around a crime of passion and adultery. The men wear dark suits, gangster-like hats and smoke cigarettes endlessly. The women wear elegant dresses and luxurious jewellery; they move around fluidly to display their sex-appeal. Everything is meant to convey American lifestyle, and Los Angeles transmits a constant air of menace. Richard Schickel writes in his BFI Classics that Wilder has ‘deliciously proved the writerly adage that landscape is character. You could charge LA as a co-conspirator in the crimes this movie relates.’ Thus one of the greatest achievements of Double Indemnity is to create a specific film noir mood of danger and attraction. An atmosphere that echoes the character’s immorality, and that is brilliantly conveyed through the particular use of low-key lighting as a visual representative of the protagonists’ psychological states.

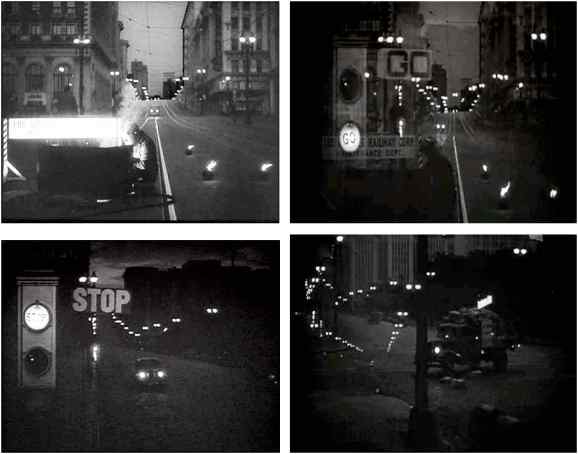

Much has been said about the use of low-key lighting in film noir. Like painters, cinematographers create an effect of chiaroscuro, and darkness tends to dominate the shot composition. Double Indemnity seems to be sculpted by light (and absence of light), anchoring the movie within the film noir tradition. The credits and the opening sequence of the film set the general tone and are representative of the film’s whole aesthetic. The shadow of a man on crutches, in backlight, walks towards us and plunges the screen into darkness. It fades to a deserted street in Los Angeles, at night time. A speeding car appears completely out of control as the haunting, heavy-beat music of the credits changes to a fierce symphony, stressing the urgency of the situation. The car can be seen as a metaphor for the impatient Walter (Fred MacMurray), who has run all the spotlights in his relation with Phyllis (Barbara Stanwyck). In the foreground, workers fix the road and scatter lanterns of fire on the ground. Flames indicate danger, passion and damnation, themes directly addressed by the film. A luminous sign stating “Los Angeles Railway Corp.” ironically foreshadows what will be a major space in the storyline, the train station. The car runs a red light and finally settles in front of a dark building. The only apparent sources of light are the street lamps and the car’s lights, which stay visible during the transition between shots: they allow the dissolves to occur. They remain on screen up to the last second and haunt the audience’s vision, like a guilty man’s consciousness… Hence, the audience is given clues about the themes, the setting, the character’s state of mind and what will happen later, in the space of twenty seconds.

In film noir, lighting implicitly develops key points around the story and the protagonists. It hides them from the audience’s sight, and wraps the plot in enigmas and secret crimes. Yet Double Indemnity adds in an extra layer of complexity – lighting also reveals the hidden evils within the characters. Thus, it is used as a narrative feature which puts aspects of the story and of the characters into visual form. Wilder and his director of photography John Seitz play with light to portray the characters’ conflicting emotions. The juxtaposition of brightness and shadow parallels the unsteady moral consciousness of Phyllis and Walter, who both wobble between good and evil, love and lust, virtue and crime. As Schickel claims, Double Indemnity is ‘a drama about light, about a man lured out of the sunshine and into the shadows’ . At the beginning of the film, sun covers the city of angels and shines through the blinds of the insurance’s offices and the Dietrichson’s house. It is in this sunny ambiance that Walter meets Phyllis, wrapped in a white towel after sunbathing. Everything shines about her: her jewels, her white dress, her nudity. Walter has been blinded by her, a bright artificial sun, and from there rain and darkness reign. He has literally been taken out of the sunshine into the shadows.

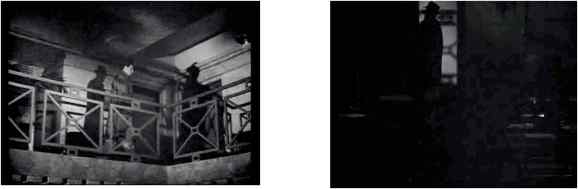

In many scenes, Walter’s shadow takes an unusual and meaningful space within the frame, acting as a constant menace. If Walter succumbs to his desire, then his shadow – his guilty consciousness – will follow him all his life. Again in the opening sequence, Walter walks into Pacific All Risk buildings at night, and the darkness of the hall envelops him completely. He crosses the balcony and walks side by side with his enormous silhouette constantly reflected on the walls, which overpowers his large body. In Keyes’ office, it is very difficult to distinguish between Walter and his shadow, as if they had become equals. Without further plot details, we already know that Walter is lost: he has embraced his evil counterpart and remains confined in a world of obscurity.

This world of obscurity is also conveyed through the sharp-witted dialogues and the neurotic soundtrack that contribute to the film’s grandeur. Wilder and Raymond Chandler produced jazzy dialogues, with a dark sense of humour. The actors say their lines promptly: they fight each other through speedy cross-talks. Yet Walter and Phyllis both use speech for different purposes, which reveals their diverging intentions. Walter stereotypically calls Phyllis ‘baby’, as if he wanted to possess her. In his apartment, after they have decided to kill Mr. Dietrichson, Walter wishes they had pink wine to celebrate, to create a more romantic atmosphere, but Phyllis dismisses him by saying Bourbon is fine. While his intention is clearly sexual, she wants to get on with the job in the most pragmatic and efficient way. Her intentions are murderous and greedy, and her relation to Walter is purely manipulative.

The voice-over is common in film noir (Wilder uses the same process in Sunset Boulevard) and parallels Cain’s use of the first person narrative. Within the flashback, Walter’s wry voice guides the audience throughout the entire film. Looking at the past, he acknowledges his fatal sexual attraction to Phyllis and is aware of the mistake he has made. ‘I killed him for money and for a woman. I didn’t get the money and I didn’t get the woman.’ The voice-over builds suspense as we are directly drawn into the story and wonder what has happened. And let’s not forget the music, crucial to the building of the atmosphere. Artfully repetitive, it accompanies the spectator through his investigation of the Dietrichson affair.

Wilder’s direction is impeccable, and actors play their role with dexterity and intelligence. The choice of cast has contributed to the film’s popularity: Barbara Stanwyck was the highest paid actress in America at the time, and Edward G. Robinson had been a star since the successful Little Caesar. Fred MacMurray was more famous in light comedies, but the role of Walter allowed him to show the full variety of his acting talent. But it really is Stanwyck’s sophisticated performance that stands out, still memorable after seventy years. Wilder has said of her that “she was as good as an actress as I have ever worked with. Very meticulous about her work.” At the time, few actresses agreed to play evil women, but Stanwyck took risks and made of Phyllis the perfect femme fatale. She is attractive, alluring, powerful and in control of the situation. Wanting her is fatal. Also, the relationship between Walter and Keyes (Edward G. Robinson) is fundamental, and warmer than in the novel. ‘It’s the love story of the picture’, stated Wilder. Both men complement each other, such as the matches symbolize. Keyes acts as the moral monitor of the story, a figure that Cain could never bring himself to write. Yet it allows the audience to sympathise with Walter, and creates a poignant new ending: he dies in the arms of his friend after confessing, and gets a sentimental farewell from the audience, whereas Phyllis dies alone.

Wilder’s ingenious craftsmanship of lighting, sound, dialogue and performance succeeds in making the film a real chef d’oeuvre. All the cinematographic qualities of Double Indemnity contributed to its enormous impact on film history: everyone remembers these beautiful black-and-white shots, like lonely Edward Hopper settings, and the actor’s brilliance. The techniques used are more than simply aesthetic choices: each one is meant to remind the audience of the danger of desire. The means of the film can be seen as cathartic and purgative; by bringing out the worst in the characters, it teaches us to resist to our cruellest cravings.

Works Cited

– Blakeney, Catherine, ‘An Analysis of Billy Wilder’s “Double Indemnity”‘, StudentPulse (2009) accessed the 13/02/2014

– Gemünden, Gerd, A foreign affair: Billy Wilder’s American Films (New York: Berghahn Books, 2008)

– Hanson, Helen and O’Rawe, Catherine, The femme fatale: images, histories and contexts (Basingstoke, Hampshire, UK ; New York : Palgrave Macmillan, 2010.)

– Lax, Eric, Woody Allen: A Biography (New York: Alfred A. Knopf Inc, 1991) pp. 37-8.

– Mills, Michael, ‘Double Indemnity: An in-depth look at the classic’, Moderntimes (2007) accessed the 13/02/2014 <http://moderntimes.com/double/>

– Schickel, Richard, BFI Classics Double Indemnity (London: British Film Institute, Palgrave Macmillan, 1992)

What do you think? Leave a comment.

It’s overrated. The snappy dialogue, the chemistry between the leads, and the psychological tension are all there, but don’t really hit the heights.

One of the finest films ever made.

It has everything- good casting, tight direction, great dialogue and one of the best musical scores ever.

I saw this again in a HD video format. I haven’t seen it in years.

I agree – wonderful film. My favourite from old Hollywood. Perfect in every respect.

OK Suggest something better.

can anyone name other film noirs which have similar tone and plot?? i have seen sunset blvd. touch of evil, maltese falcon, the big sleep, wrong number, gun for hire, the killing, blood simple (recent noir). so with the exceptions of these movies, give me some more names!!!

First thing is watch Out of the Past, with Robert Mitchum, Jane Greer, and Kirk Douglas. IMO, this and Double Indemnity are the best noirs ever made. BTW, when you list The Killing, do you mean The Killing (not familiar with it) or The Killers? If the former, see the Killers (1946 version, of course, with Burt Lancaster and Ava Gardner). Other great noirs, off the top of my head–Criss Cross (Lancaster), The Woman in the Window (Edward G. Robinson, Joan Bennett, Dan Duryea), Scarlet Street (Robinson, Bennett, and Duryea again), Gilda (Glenn Ford, Rita Hayward), The Asphalt Jungle (an ensembe cast with young Marilyn Monroe in a small part), The Big Heat (Glenn Ford, a young Lee Marvin), Kiss of Death (Victor Mature and a terrific Richard Widmark in his first film), Murder, My Sweet (Dick Powell as Phillip Marlowe), The Starnge Love of Martha Ivers (Van Heflin, Barbara Stanwyck, Kirk Douglas), Night and the City (Widmark).

Also, if you liked Double Indemnity, then I guess you should try The Postman Always Rings Twice (again, the 1946 version). It’s adapted from a novel by James M. Cain, who also wrote the novel Double Indemnity, and has a somewhat similar plot. if my recommendation sounds half hearted, it is. Although this is a much loved noir (unusually from MGM), I just don’t care for it much despite many tries. Lana Turner is gorgeous, but not much of an actress and John Garfield leaves me cold here. For me, the highlight is a young Hume Cronyn in a supporting part as an attorney. But most noir fans disagree with me, so give it a try.

FWIW, I Sunset Boulevard is a great, great film, but I wouldn’t classify it as a noir.

While more neo-noir than regular-noir, Chinatown is a fine, fine film, an almost perfect mystery film : )

Out of the Past is the best film noir I’ve seen; it’s the cream of the crop in the genre as far as I’m concerned. But this one is in my top 5 for sure.

I didn’t like Out of the Past. I don’t get why it is so popular, but I guess it’s subjective.

Good analyses. It is a terrific and suspenseful movie.

great breakdown of film noir… especially for someone that is not so familiar with the “genre” (If one can truly call it that….) I have not seen double indemnity in many years and this most definitely makes me want to revisit the classic!

Good analysis on the formal elements of a classic film noir! I think a large part of what makes classic noir – that genre that is meant to remind us of “the danger of desire” – is the threat to American masculinity in the post-war era. We definitely see this in Double Indemnity – the good man is essentially lured by the hypersexualized woman into becoming the poorest and least honorable version of himself. He initiates the scheme to plot and murder, but he furthers the schemes with her encouragement, something that is motivated by sex just as much as it is by a desire for money and power. From what I remember, the film tries to win the audience’s sympathy for the insurance salesmen who refuses to take responsibility for his actions. A lot of these same themes run through American culture once military men returned to find their positions in the work place and at home to be successfully occupied by women.

I was recently studying film noir in one of my classes–it was a graphic novel class though. I’m pretty new to the genre so this article was an interesting and informative read. I definitely want to watch this film now.

I absolutely love this film. I came across it when I did an Independent Study on film noir, and it became one of my instant favorites (as well as the 1941 version of “The Maltese Falcon”). Film noir is such an interesting and complex genre, because it includes aspects from so many different influences. I think “Double Indemnity” is one of the better examples of all of those influences working well together.

I’ve only seen this film once, but it stands out for its impressive use of lighting! Especially in the opening sequence. Great analysis!

Much like in the previous comment, I too have only seen “Double Indemnity” twice. But the author of the referenced analysis of the classic movie is impeccable. I’ve always been a fan of Billy Wilder since first watching one of my favorite films of all time, Wilder’s timeless work of cinema “Sunset Boulevard.” He was the perfect embodiment of the nearly extinct genre film noir. Often times when teaching or offering up my own analysis or critique, the general public appears to think that the film noir genre is limited to detective movies. Although detective movies played a large part in the film noir genre, the most iconic films of that genre and 1940-50s Hollywood were more dramatic and mysterious. It’s been years since Its been many years since film noir was the popular genre of film in Hollywood. There was once a time when nonlinear, dark, and convoluted films filled with labyrinthine plots were very popular. Like “Sunset Boulevard,” “Double Indemnity” laid the ground work by which all other film noir style movies would be judged. Everything from the dying or doomed protagonist to the mysterious individual to the lighting patterns and dialog. I appreciate the author’s in depth analysis of a movie that helped set the standard in what was once a time tested and popular genre during Hollywood’s golden era.

Great Article! I studies this film in A2 film studies and it really is a land mark in the Noir Stylistic.

Have to admit, I’m sort of obsessed with the use of the voiceover/flashback mechanism in film noir, and Double Indemnity in particular. This mechanism creates a schism between past and present for Neff, and the film images acquiesce to his own retelling of events — he resorts to language in order to make sense of what does not, but, as you talk about, that linguistic effort is transformed into striking and expressive visuals. I think noir’s the ultimate genre if you want to talk about adaptation — interestingly, although it advanced (or at least was a training-ground for the technology used to advance) the ways film could be meaningful, the noir cycle bears indelible the marks of literature throughout.

Hi, what is your first and last name so i can quote you and give you credit?

Hi Ang, yes this is my full name, first and both last names. I appreciate this a lot, thank you! I’m glad my articles can help out people in their research. Can I ask you in what context you are citing this?

This is my second favorite film ever.

Fred MacMurray calls Barbara Stanwick “baby” a total of 27 times during the course of this movie! I love this movie and have watched it scores of times and it always amazes me how many times he says baby!

I am 91,female and I remember well seeing that movie so long ago. It has remained in my memory all these years as one of my favorites. Today seeing it, the fact it was in black and white just is not in the forefront of your mind. There is something to be said about black and white being a large positive in many of the films of yesterday.

Stanwyck was also mainly a protagonist, so her role here is a change of scenery.

Film noir is well known for its flawed characters. Who appears to be the most flawed in this story? Explain

Interesting commentary, but there are so many errors in the language that it’s unclear if it was written by a non-English speaker or just wasn’t proofread. You won’t be taken seriously unless the level of the writing improves.

I would be willing to read your pieces in advance and make necessary corrections.