Easy Rider: An Artful American Souvenir

(SPOILERS)

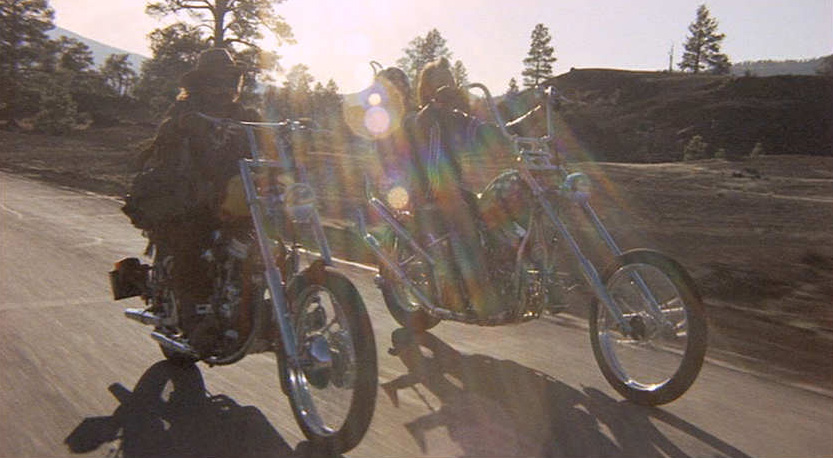

Two men went in search of America, and couldn’t find it anywhere. Easy Rider is one of the first great American art films to surface during the late 60s. It blew a kiss to cinema as much as it was a commentary on the growing social milieu of the time including the hippie movement, a drug-use and a less commercial, more communal lifestyle. In many ways, the film is a documentary in that sense. In many ways it’s not.

Easy Rider is a gem of minimalist filmmaking and indie art that will forever be a memoir to the American sixties counter-culture. Dennis Hopper, the director of the film, won Best First Work at the Cannes Film Festival in 1969, and the film is hailed as a cult and hollywood classic. This article will examine all filmmaking aspects of the film, their meanings, and why the film is very much an artful souvenir of the American sixties.

The Characters

Throughout the film the audience follows two protagonists: Wyatt (nicknamed “Captain America”) and Billy. Peter Fonda and Dennis Hopper (writers) have reported that these names are references to Wyatt Earp and Bill The Kid. Wyatt wears a leather jacket with an American Flag on it (with an Office of the Secretary of Defense Identification Badge on it). His motorcycle and helmet are also themed in American-flag designs. Billy wears native-American style clothes. Wyatt is more open and friendly with people, whereas Billy is more reserved and hostile. Wyatt and Billy are chill, free-thinking, worry-free, finding the simple joys of existence, and looking for freedom. They represent everything America is not.

These two characters remain self-driven throughout the film to get to Mardi Gras in New Orleans. The audience does not know where they come from, or how long they’ve been on the road, and in this way the film is a portrait of lone existentialism.

The other notable character in the film is George Hansen (Jack Nicholson). George is a lawyer for the American Civil Liberties Union that Wyatt and Billy meet after they’re thrown in jail for “parading without a permit.” George travels with Wyatt and Billy for a short while before being brutally murdered in his sleep while Billy and Wyatt are only injured. George, while being labeled as an “alcoholic square,” says some of the most profound things throughout the film, such as: “They’re not scared of you. They’re scared of what you represent to ’em.” In regard to why so many are hostile or hateful toward ‘hippies.’ However, the topic of this conversation between George and Billy is subsequently freedom–true freedom. The freedom that comes from individuality, rather than popularity; the dichotomy of which is the main theme this films carries with it.

George is a seemingly vague and easy-going guy, and is in the film for only 17 minutes — why? What does George represent in the existential landscape of this narrative? Perhaps George is the rarity that is the American Renaissance Man of the sixties. Perhaps he represents a catalyst of the easy-going lifestyle Billy and Wyatt have adopted. It’s unclear. What is clear is that George harbors truth in his character, and he meets an untimely and abysmal end all too soon–just like the two protagonists.

The Journey

On the road, Billy and Wyatt meet many hitch-hikers and random towns-folk. Each has their own interesting backwater residents, such as the first hitch-hiker they pick-up who tells them: “I’m from the city… Doesn’t matter what city; all cities are alike.” The film continues to make a commentary in this manner of existential enlightenment–ever so aware of place and time but ever so careless of its meaninglessness. Wyatt, at the first farm him and Billy stop at, comments that “it’s great that people can live off the land, do their own thing in their own time–live simply, and truly.” Throughout the plot, Billy and Wyatt get side-tracked with random groups of people, and enjoy the simplicity of their audacity to the common milieu at the time, and these people’s collective state of grace is blatantly attractive to Wyatt especially.

Throughout the film the protagonists are thrown in jail, almost murdered, and then actually murdered. And they’re just going on a road trip in America. The ending of the film is shocking. It leaves the audience in a state of paranoia and with a sense of injustice. Both protagonists are senselessly murdered by ‘rednecks’ for simply being hippies. George’s earlier monologue did foretell this potential outcome: “It’s real hard to be free when you are bought and sold in the marketplace. Of course, don’t ever tell anybody that they’re not free, ’cause then they’re gonna get real busy killing’ and maimin’ to prove to you that they are.” This is the outcome of Billy and Wyatt’s search for America. Gunned-down–by what? Fear, pride, insecurity, hatred, and even freedom. These things all lie at the root of American idealism.

In this way, the film is very nihilistic. The film was unclear of the true motivation behind these two men’s journey, and on it, they’re senselessly murdered only after they reached their goal and being somewhat disappointed by it.

The First Great Drug Trip

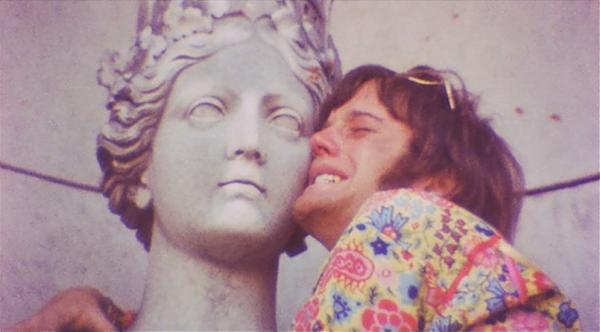

Dennis Hopper’s visionary apex of creating one of the first great drug trip sequences in cinema was brought to life through this film. The trip happens at Mardi Gras, New Orleans, when Wyatt, Billy, and some girls take LSD. The sequence lasts roughly two minutes total, and consists of artistic filmmaking that helped breed the New Hollywood era of cinema in America. The trip takes place at St. Louis 1, a Catholic cemetery in Mardi Gras. The sequence contains incoherent camera movement around the cemetery, metaphorical film editing, and non-diegetic sound to bring a drug-induced perspective on-screen.

The poetic film editing involves the use of framing and pulling focus, combined with jump-cuts to create metaphors with seemingly unrelated things, such as an eye ball and the sun. The trip also begins and ends with a bright orange sun going out and then coming into focus. The flow of the trip is elevated with shots of tree branches, estranged people running around doing strange activities. Wyatt and his female friend are seen standing/sitting together in between two cement walls; it seems uncomfortable and strange that they’re just standing there, which makes it all more surreal for the viewer.

Wyatt is seen leaning on a female statue for much of the drug trip, and delivers a soliloquy to it through voice over. Dennis Hopper wanted Fonda to refer to the statue as his mother–who committed suicide when Fonda was ten. Fonda initially declined, but eventually did–which is why Wyatt calls it “mother” in the film. Later, the trip recounts places, people, aesthetics, memories, and fears. Due to the fact that the audience has know direct knowledge of all these memories or aesthetics, they are forced to related the trip to themselves and conjure their own meaning between what’s being said and what’s being seen. The use of voice over is a key ingredient to any poetic filmmaking, as Robert Bressson once said that when using it (voice over), it forces the ears to go inward, and the eyes to outward.

After the trip, when Billy is exclaiming that he and Wyatt “did it” and that they’re “rich,” Wyatt simply replies “we blew it.” This drug trip, for Wyatt at least, is perhaps a sort of crushing awakening from the reality of the state of the union, the state of his lifestyle, or perhaps both.

The Philosophy

Easy Rider is a portrait of existential nihilism, both in story and aesthetic, and was originally titled “The Loners.” The story is beautiful, bleak, and full of ideas from Henry David Thoreau and, of course, Voltaire (one of his famous quotes: “if God did not exist it would be necessary to invent him,” is seen by Wyatt on a hippie’s tent wall in the film). Wyatt and Billy undoubtedly live a life of civil disobedience and a longing for the wistful joys of non-materialist life. While sly, there is undoubtedly a critique/satirical nature to the film where extremism is essentially the downfall to the chill lifestyle the protagonists have. The reasons that they are thrown in the jail (parading without a permit), the reasons that they are almost murdered the first time, and the reasons they’re murdered in the end, all seem ridiculous and extreme–very conservative American.

Fonda and Hopper didn’t write most of the film, and crafted it as they went along–often getting real hippies from nearby communes to hold the camera and equipment for scenes. Hopper and the main cast were supposedly drunk and high for a good portion of the production, and did this to incorporate as much of an authentic approach to the essence of the film. They wanted to capture a simplicity about the rawness of this lifestyle, and America in the sixties. Combining a film’s aesthetics with its essence (whether it with be a narrative or non-narrative work) is the grandeur of art film–as is presented here.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

I loved the way it’s paced.

Nice stuff. Watching it feels like an adequate history lesson.

Very good analysis. You made some great points about its depiction of the existential aimlessness and nihilism of 1960s America, but it might have been nice to see an extra section of the cultural impact of the film. It is often attributed as being the birth of of American motorcycle subculture as we know it today. Prior to, motorcycles were thought to be “the poor-man’s car,” which became popular among returning WWII veterans who could not afford that Corvette they were promised in the recruitment videos (thus epitomizing their disillusionment with the American Dream after fighting so hard to defend it) and had acquired mechanical engineering skills while oversees (thus birthing the associations between mechanic culture and machoism). After Easy Rider came out, many excited spectators flocked to buy motorcycles, hoping to experience the freedom of adventure as depicted on screen for themselves. It’s interesting to think of that in light of your ruminations on plot’s existential meaninglessness. Did these viewers simply miss the point of the film, or is there something attractive about such aimlessness (albeit hollow and unsatisfying) lying at the heart of their journey?

The cinematography is awesome and the film overall is great.

I was shocked to learn that Hopper was the director.

I hated Easy Rider from the start and given its ‘classic’ status I hoped that it would improve as things progressed. Sadly, it remained bad from start to finish.

Best soundtrack ever.

It is clear depiction of a definitive time in American history.

One thing that bothered me in Easy Rider is a montage that happens towards the end of the film

Yeah, it goes on so much longer than it needs to that it just comes of as forced.

Easy Rider was one of the biggest surprises I ever had.

I could never understand why a film about two anti-society hippies on chopper bikes going across America taking real drugs doing a whole lot of nothing became should become such a revered and awarded film. But now I do. Now that I’ve actually seen the film, I understand completely…

The iconic and tragic ending came as a total surprise to me.

A great film with amazing spiritual and physical values!

Was Easy Rider was influenced by Huckleberry Finn? Some similarities, it seems.

Interesting article, cool movie. Another great manifestation of the frontier story and the American picaresque.

Thoroughly enjoyable Read. Perhaps have a section of examples from other “radical” movies of the time that helped changed the shape of american cinema?

One of the great classics of the 20th century. You can’t get any better a great biker film than this. Great soundtrack I own 3 of them.

The LSD scene in the graveyard is one of the best scenes in history.

When the film first came it was seen by many in the audience as aimed at the South, a severe criticism: The two riders are killed in the South. The Civil Rights movement was taking place and the movie was reflecting how the South was seen.

Easy Rider strikes me as a film that very much is a piece for that specific time and seems to have less lasting influence than is belied by those that very much look at films, almost obsessively.