Fantasy Writing in the Age of Reason to Today

Fantastic Inspiration, Rise of the Fantasy Novel: Drawing from the Age of Reason to Today in your fantasy writing

Fantasy writing draws from a plethora of sources. From the early mythologies of Classical Antiquity to reflecting the social changes of the Renaissance and the Middle Ages, to the social morality stories that align realism and mythology in the Age of Reason, all the way to the birth of modern Fantasy and its myriad of forms. Fantasy literature is a diverse, multilayered creature that draws on stories from across human history. It remains one of the most popular genre categories in publishing today. Fantasy as we know it today can be back tracked to the popularity and rise of J.R.R. Tolkien, but Lord of the Rings did not succeed in isolation. Although held up as the turning point for the movement of popular fantasy publication, it was merely one step in the rising popularity of fantastic stories that emerged from the Age of Reason (1685 to 1815) to today.

The Age of Reason

The Age of Reason represented a change in the interest of both academics and readers, and saw the rise of realist fiction. Fantasy continued in two main forms: the literary fairy-tale and the Gothic romances. At the beginning of the seventeenth century realist prose was the primary medium for fiction throughout Europe, however, surprisingly, fantastic narratives continued to be written and read. During this period the literary fairy tale also flourished with the works of Madame d’Aulnoy, most notably Les Contes des Fees (Fairy Tales, 1697), and Contes Nouveaux au Les Fees a la Mode (Fairies in Fashion, 1698), and Charles Perrault’s Histoires ou Contes du Temps passe (Tales and Stories of the Past with Morals, 1697), along with his translation of the Latin poet Gabriele Faerno’s work Fabulae Centum (100 Fables) in 1699, and a french translation of The Arabian Nights (1704-1717) by Antonie Gallard.

The fairy-tale was not originally intended for children, but rather for sophisticated adult readers, yet Perrault chose to write for children and is often credited as the founder of the modern fairy-tale. Like Ovid, what Perrault and d’Aulnoy achieved, and later the Brothers Grimm and Hans Christian Andersen, is collect together old folk-lore and fairy-tales and publish these works for posterity. This action has allowed the traditional tales to remain in the public eye and continue to be a source for fantasy writers. In fact, Emma Bull in War for the Oaks has her character Eddi, when confronted by the presence of Fae, reflect:

Fairy tales. That was all she could remember about fairies, and as she tried desperately to recall the ones she’d heard or read, she realised she knew of few with fairies in them. And the two before her were nothing like Rumpelstiltskin or Cinderella’s fairy godmother. Elegant Oberon and Titania, silly Puck – Shakespeare was no help, either. These two, with their changing shapes and their offhand cruelties, had the roots in horror movies. (31-2)

Bull War for the Oaks

Bull’s character remembers the childhood fairy tales and the stories of Shakespeare, but Bull actually draws on the older traditions of fairy tales. Although these collectors of tales may not have contributed new ideas, only adapted context and style to fit their readership, their work was invaluable in preserving oral tales that may have been lost. It is in a manner the rise of realism that ensured this, for as Maureen Duffy indicated this era preserved fairy tales as they had been told for several hundreds of years, a form that has remained in use still today. Since the ‘great age of the collectors had begun in England and Scotland and those without the creative ability to tell stories for themselves were able to enjoy the release of the fairy convention under the scientific guise of collecting and preserving.’ 1

It is tempting here to deconstruct and examine every fairy story, but such a task is well beyond the scope of this article. Rather I would direct the reader to the original sources. Fairy stories were originally told as a form of oral teaching stories, which meant they were designed to be memorable, and to help pass on messages of social norms and morality. Many fairy tales and folk tales, when examined in their original form, reflect clearly specific taboos, morality and lessons that were important to be departed. The original Greek myths were used in this way, and similarly, there are strong religious messages present in most original fairy tales. The way in which fairy tales have been interpreted today often are used to represent new social norms. Most Disney interpretations are an excellent example of this, in both good and bad ways, as they represent particular social concepts often linked to gender.

Gothic Romance

The second important development of this period, of course, is the Gothic romance. Dennis Kratz argued that ‘the Gothic belongs less to the history of fantasy than to the horror novel, since its supernatural elements are often given naturalistic explanations; but the Gothic too represents an attempt to return the irrational to literature.’ 2 The Gothic draws on elements of terror and fear, which are as much a part of traditional folk-lore and fairy-tale as the more popularised elements of heroism and bravery. One only needs to spend time with an original version of ‘Cinderella’ to understand this fact. The popularity of this genre is a reminder that even during a period of strongly realistic novels, there consisted a fascination with the darker side of the irrational that lives on.

To a certain extent the continuation of romantic prose was a reaction to the “cult of reason” and produced the Gothic novel. 3 The first novel, generally regarded as the beginning of the genre, The Castle of Otranto (1764) by Horace Walpole is the tale of Manfred whose obsession with an ancient prophecy leads him to destroy his own life. Walpole was the forerunner of the genre and was followed by a number of notable writers: Charles Maturin, Matthew Gregory Lewis, Ann Radcliffe, Bram Stoker, Edgar Allan Poe and more.

A number of critics have made links between the Gothic genre and modern fantasy for fairly obvious reasons, mainly the use of supernatural creatures and the emotional atmosphere present commonly in both genres. Eric Rabkin wrote that ‘Gothicism is a literary movement that helped create the climate for the emergence in the nineteenth century of modern science fiction, the thriller, detective fiction, and the psychological novel. This whole movement, like a genre, emerged out of a confluence of earlier literary types and spawned a series of new genres even at the same time that the mainstream of the movement continued and developed on its own.’ 4

One of the genres were a close alignment to Gothic remains focally present is the genre of Urban Fantasy. As such it is understandable that it is often perceived that ‘contemporary urban fantasy started as an offshoot of horror fiction rather than sf/fantasy but has blended with other genres, most notably romance and mystery.’ 5 Added to this is the similarities Urban Fantasy shares with elements of Gothic literature. A genre obsessed with concepts of restriction and the taboo it can be argued that it is a more fantastical and updated version of the Gothic, especially from the branch from Matthew Gregory Lewis, where ideas of masochism and algolagnia can be taken to the extreme. Indeed, the anxiety that is a core element in urban fantasy is equally important in the Gothic, which Michael Moorcock discussed: ‘The popularity of the Gothic rose as the impact of the Industrial Revolution increased, reflecting, symbolising and even “explaining” the anxiety felt by those who witnessed radical changes in the world they knew. There are parallels today between the popularity of science and major social changes which are now taking place.’ 6

Modern anxieties caused by the overpopulation of our cities, isolation through technology, and increasing environmental concerns, all add to the fears Urban Fantasy attempts to draw upon in its creation of the supernatural. However, many of the original elements set out in Walpole’s The Castle of Otranto are also present: claustrophobic confinement, subterranean pursuit, supernatural encroachment, lethal predicaments, abeyance of rationality, possible victory of evil, supernatural gadgetry, and a constant vicissitude of interesting passions. 7 However, there is a strong deviation in the use of place, as Gothic has a tendency to focus on isolated, ruined or ancient locations while Urban Fantasy maintains a primary setting in an urban environment. Yet a strong sense of the atmospheric similar to Gothic is often maintained, where the supernatural crosses into the traditional idea of being viscerally unsettling. The treatment of the unnatural creature is still described in a manner that is intended to disturb us, ‘the real horror lay in subtler things. The vampire’s black robes were rotting and falling apart. Graveyard lichens and moss grew here and there on the dead skin.’ 8

Perhaps the best demonstration of the endurance of an influence is Dracula and the modernised myth of the vampire. The original novel Dracula by Bram Stoker was published in 1897. It draws on much older Middle Ages Transylvanian folklore and history, but was adapted to reflect the morality and concerns of English society. Since the original novel (which is also not the first vampire novel), a myriad of reinterpretations have evolved from this source. The inclusions of the 1897 novel presented the concerns of the immoral influences of Eastern Europe, of foreigners in general, of the impact of a loss of morality by women aligned to sexuality, and the fear of disease. These thematic concerns were particular to this period. Yet, in the later interpretations of the vampire it can be seen how the monster is used to represent other threats to the moral strengths of society. Film interpretations have done this continuously. For instance in the 1958 Horror of Dracula film the focus is the corruption of the allure of sexuality, a social concern of the period. The 1972 Blacula uses the vampire as a representation for colonisation and although a problematic portrayal, the film does address concerns around race rights during this period. The 1994 Interview with a Vampire, and all of Anne Rice’s novels, use the concept of the vampire to explore questions about immortality, but also about diverse sexuality. Regardless of the interpretation, the vampire is still most often used within the context of its original Gothic origins. It is a creature designed to be Other, to be outside, and to represent threads to the social norms.

The following discussion of Victorian and Early 20th Century periods are designed to begin to list the different influences that rose to popularity and have implications for modern fantasy. It is again, not a comprehensive listing, but rather an esoteric skipping stone outline of some of the influences that can easily be identified as still influential in today’s contemporary fantasy literature.

Victorian Fantasy

The 19th and 20th century saw the continuation of a number of styles of writing that have contributed to the modern fantasy. A change in perceptions began to be reflected further in the interests of the general reading public as ‘in 1825 something very extraordinary had happened. From being terms of derision, or descriptions of daydreaming, words like “fantasy” and “imagination” suddenly began to take on new status as hurrah-words. People began to feel that the very unreality of fantasy gave its creations a kind of separate existence, autonomy, even a “real life” of their own.’ 9 Two seminal pieces of the Victorian Era were George MacDonald’s The Princess and the Goblin (1872), a fantasy novel about the adventures of Princess Irene and the goblins that live in her kingdom, and William Morris’ fantasy novel The Wood Beyond the World (1894) about Golden Walter’s voyage to a faraway land, and The Well at the World’s End (1895), a romantic fantasy that draws on the Chivalric romance tradition.

Nonsense Literature

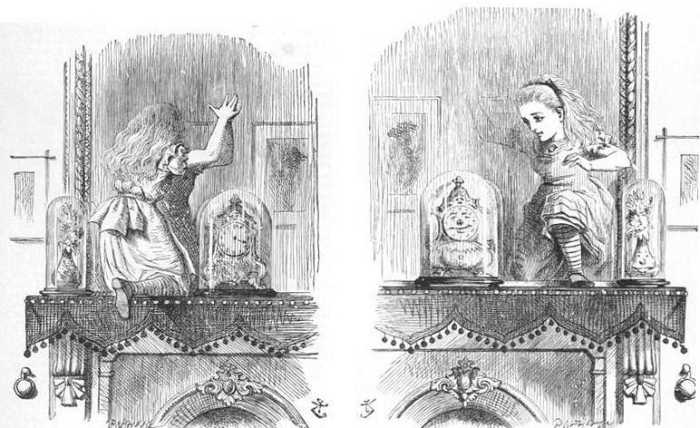

Nonsense literature was a particular fad during the Victorian era most popularly used by Edward Lear and Lewis Carroll. Lear popularised the limerick form and described his own works as “nonsense, pure and absolute.” 10 This genre of literature is difficult to categorise fully and to a degree was linked through the direct interactions of a small number of authors during this period. Caroll’s most famous nonsense work is the poem ‘Jabberwocky’ published 1871, which develops, akin to ‘Hunting of the Snark,’ a series of portmantua words and constructed words based on a pleasing sound pattern. Nonsense literature remains present in many older and many newer forms, not only limited to poetry, but can be seen in elements of comic fiction and surrealist fiction. It is commonly literature that draws attention to language as a thing itself. 11

‘Twas brillig, and the slithy toves

Did gyre and gimble in the wabe;

All mimsy were the borogoves,

And the mome raths outgrabe.

“Beware the Jabberwock, my son

The jaws that bite, the claws that catch!

Opening lines from Lewis Carroll’s ‘Jabberwocky’ (1871) included in Through the Looking Glass.

Alice in Wonderland can be considered an extension of this form, and although also fits within the scope of the rise of children’s literature, it was not didactic in nature. Rather the silliness of the narrative, the embedded games, language of flowers, and the inclusion of Carroll’s nonsense poems, mean it fits better within this scope. One aspect of this period was also linked to the rise in travelogues and a general interest in scientific discoveries, which was the inclusion of undefinable creatures in Caroll’s work. This reflected the popularity of descriptions and sketches coming from new countries back to England that evoked much amusement from the general public. The nonsense literature of Carroll mimics these ideas and invites the reader to be mystified and accepting of the unreal. Alice in Wonderland (1865) and Through the Looking Glass (1871) are not the first version of portal fantasies, but their popularity and timing with the rise of cheaper publication have meant that they often represent this particular trope of fantasy literature.

Lost Race

The category of Lost Race fiction evolved alongside realism literature, such as Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness and science-fiction such as The Island of Dr. Moreau by H.G. Wells. It was a category that captured the evolving fascination with new worlds being discovered during explorations and colonisation. It also perhaps represents some of the worst contributions to the Noble Savage trope. In many ways these texts were similar in purpose to Gothic literature, in that it highlighted the dangers of the Other. Although many of these texts would work to critique or infer the problems of colonisation and scientific explorations that worked to categorise people and places, ultimately, they represent a period of insular thinking in European literature. The lost race subgenre of fantasy also owes its roots to this period with H. Rider Haggard’s tale She, which was serialised in The Graphic between 1886 and 1887. Lost race fantasy focuses on stories about lost races or strange people from lost lands or underground cities. 12 A number of The Arabian Nights tales fit this category, also alongside Haggard’s work is (Sir Arthur) Conan Doyle’s The Lost World (1912) concerning prehistoric animals in the Amazon basin, and Edgar Rice Burroughs’ African series beginning with Tarzan of the Apes (1912).

Didactic and Children’s Literature

The late 19th century saw also a range of other expansions, such as the American pseudo-folk tales such as Washington Irving’s Rip Van Winkle (1819), the moralities of Charles Dicken’s A Christmas Carol (1843), of course Lewis Carroll’s Alice books (1865-1871), and E. Nesbit’s The Book of Dragons (1899). This and also the early 20th century saw a number of popular children’s fantasies: J.M. Barrie’s Peter Pan (1902), L. Frank Baum’s The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (1900). 13 This period of works began to help evolve the considerations of what could be included in children’s literature. However, this period also represents many of the social attitudes around fantasy as being a lesser, or children’s field, when previously genres such as Gothic, Fairy Tales, Mythologies, were considered exclusively adult literature. The shift of focus to the protagonist character as a child present in such stories changed much of the dialogue around fantasy literature, from which we have not really progressed.

Early 20th century

The 20th century contains the origins of what would be considered popular fantasy today. The following outline touches only on a tiny proportion of a truly monolithic genre. It is also difficult to outline this section chronologically as many influences remain present through to today rather than falling away in dominance. For instance, discussed below is Sword and Sorcery before C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien, when in fact this subgenre really only gained popularity in the 1970s, however, the origin of this category was much earlier. What is interesting in this period is the clear ties and influences to what has come before, the way in which concepts have evolved and changed to reflect the society that has created them. The rise of fantasy in this period is also due to simple commercial elements, such as the rise of the magazine, and the decreased cost of mass paperback publishing.

Magazines

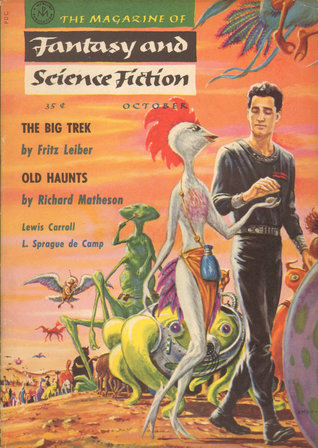

One of the most significant influences on the rise of the fantasy genre was the popularisation of the magazine, and the development of a range of themed fantasy papers. 14 The earliest was the German magazine Der Orchideengarten (1919-1921), while the American long running magazine Weird Tales (1923-1954) published a great number of famous fantasy writers including: H.P. Lovecraft, Clark Ashton Smith, Ray Bradbury, Margaret St. Clair and more. One of the longest running magazines is the Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction began in 1949 that still continues today. The magazine was popularised for a number of factors: it was cheaper to print and distribute; it was more accessible to general readers and often utilised multimodal elements to ease readers through complex texts; it allowed for authors to publish smaller texts during a period that was still strongly influenced by the periodical format; and it was accessible since they were sold through newsagents or general stores.

Comic Fantasy

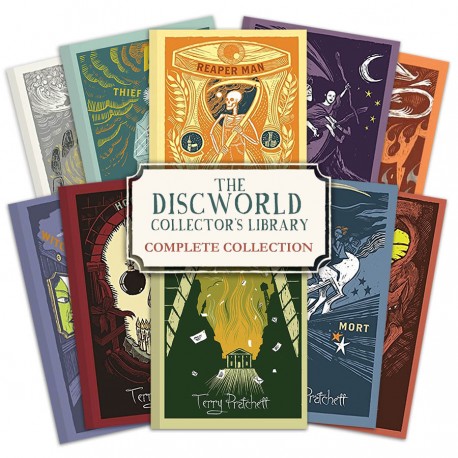

The start of the subgenre of comic fantasy began with T.H. White’s novel The Sword in the Stone (1938), based on the Arthurian legends, and has been a popular subgenre in modern fantasy with authors such as Tom Holt and the incredibly long running Discworld series from 1983 to present, which follows numerous whimsical and comic adventures on a disc world balanced on the back of four huge elephants riding the shell of an enormous turtle, the Great A’Tuin, swimming through space. Comic fantasy remains a strong category today and can be understood both through its own form, but also through parody fantasy that turns traditional tropes into a critique of itself. In many ways it could be considered a furthering of the nonsense period.

Sword and Sorcery

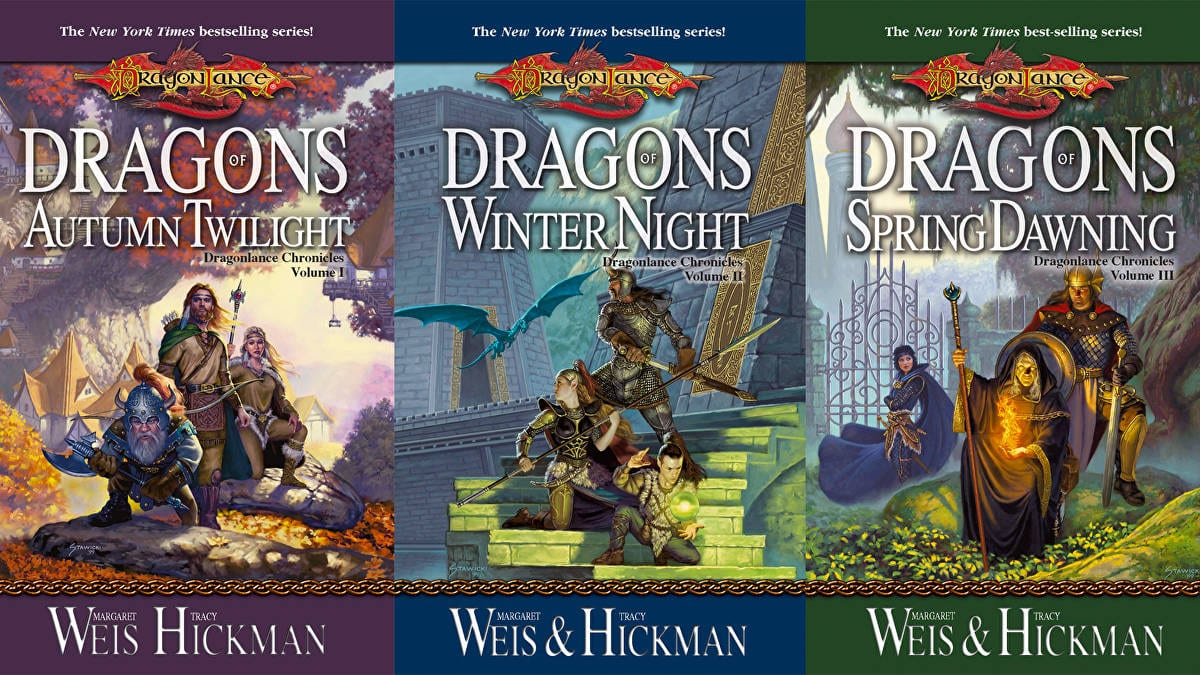

Another subgenre that has continued in popularity is that of sword and sorcery, 15 a term coined by author Fritz Leiber in 1761, two novels that were considered formulaic of the style were Michael Moorcock’s Elric (1961), the tale of a sorcerer, and Karl Edward Wagner’s Kane series (1970), about a mystic swordsman. It is out of these author’s successes, along with that of the role playing game ‘Dungeons and Dragons’, that the most commonly recognised sword and sorcery series Dragonlance (1984 to current), originally by Margaret Weis and Tracy Hickman, developed from.

This subgenre was valuable to many women writers especially, for as Charlotte Spivack pointed out, ‘In much sword and sorcery written by women, for example, female heroes play conventional male roles as warriors. Their emphasis is on physical strength, courage and aggressive behaviour. In the fantasy novels the female protagonists also demonstrate physical courage and resourcefulness, but they are not committed to male goals. Whether warriors or wizards, and there are both, their aim is not power or domination, but rather self-fulfilment and protection of the community.’ 16 The category further owes much of its inspiration to the framework of earlier models, such as the Chivalric romance and Arthurian legends, even the early sagas are often present in the emphasis on heroic journeys.

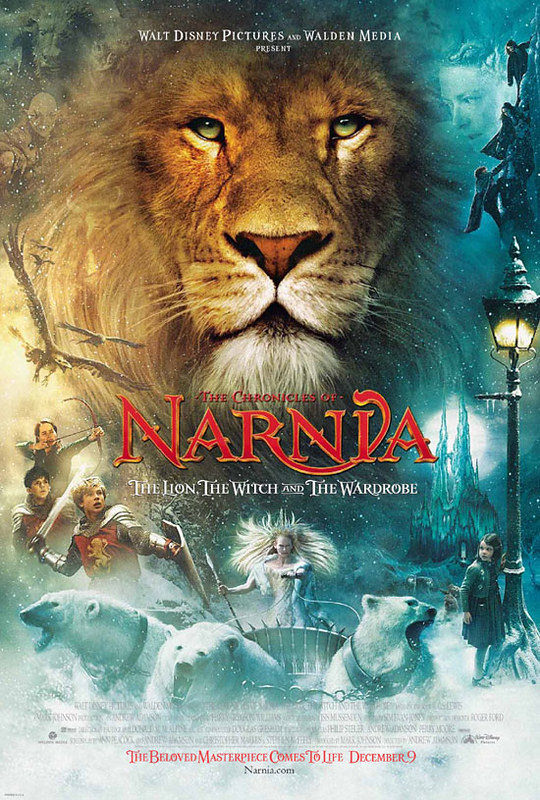

C.S. Lewis

C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien are considered the forefathers to fantasy through the manner in which their work is often used to situate other literature in the field. Where Lewis’ Narnia works, first published in 1950, are representative of the portal-quest fantasy format, Tolkien’s work is immersive or secondary world fantasy. 17 Both represent High Fantasy, which means referring to fantasy with its own developed world that includes rules and settings unique to itself. This is versus Low Fantasy, for instance most of urban fantasy, where the fantastic is directly merged into the real world, this is also often known as intrusive fantasy. It is easy to see in Lewis’ works the influence of older mythologies, the allegory of the animal is indeed quite present from the Middle Ages, while he draws also from fairy stories from the Age of Reason, and elements of the Arthurian legend from the Renaissance. Yet, his work, like Tolkien’s is still unique, beautiful and considered as categorically representative of the genre as original fantasy literature, while still clearly drawing upon older concepts.

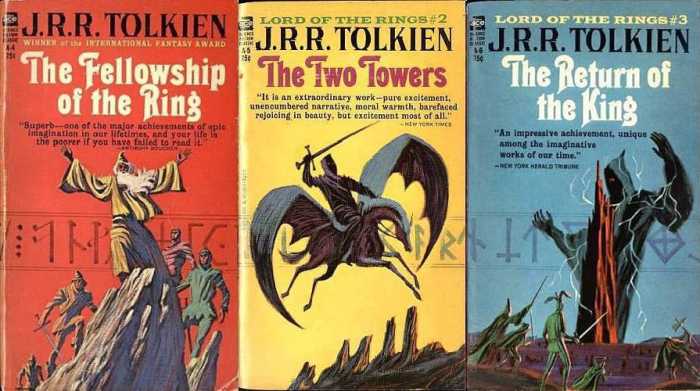

J.R.R. Tolkien

Yet truly the popularity and explosion of the genre had much to do with the success of Tolkien’s adult fantasy novel The Lord of the Rings (1954) that has gone on to be ranked as the second bestselling novel of all time. Following Tolkien was a boom of a number of similar epic or High Fantasy novels that have shaped the genre of modern fantasy. Tolkien’s work can be analysed in depth for the themes, the author influence, the construction of second world fantasy and more. At its heart it draws on Tolkien’s own immersion in original mythology, such as Beowulf, and this very influence has set the standard for fantasy to look backwards as much as science-fiction looks forward. Tolkien’s work popularised the unique creation of in-depth secondary worlds, not only through general description but through mapping and language creation. Yet at the end of the day any critic could list the myriad of other stories that Tolkien is retelling. Does this diminish the work? No, this is fantasy writing at its most categorical. Fantasy commonly works to retell older stories, old myths, through the lens of new worlds or through the lens of contemporary social values.

Post-Tolkien

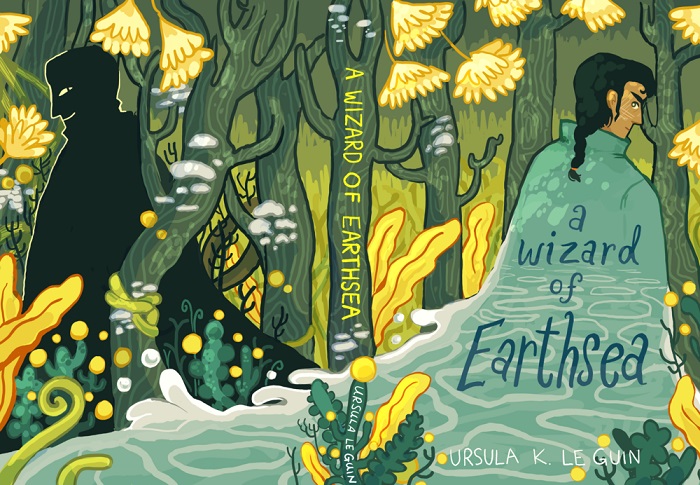

The post-Tolkien period saw a number of great successes for the fantasy genre. In 1977 Terry Brooks’ novel The Sword of Shannara was the first fantasy novel to appear on and eventually top the New York Times Bestseller list. Seminal fantasy texts have added to and adapted the parameters of what is fantasy as a genre. Ursula Le Guin’s Earthsea series spanning from 1968 to 2001 was a set of fantastic adventures in the secondary world of Earthsea, an archipelago created in almost as much detail as Tolkien’s Middle Earth. A more cynical series, The Chronicles of Thomas Covenant (1977-2013) by Stephen Donaldson, follows a leprous protagonist who passes into an alternate world and is infused with psychological undertones thus popularising the anti-hero in fantastic terms. Raymond E. Feist’s The Riftwar Saga began in 1982 with Magician, a novel following the beginnings of a young magician in a world called Kelewan based on an original ‘Dungeons and Dragons’ campaign. Also the epic long running fantasy novels of The Wheel of Time series (1990-2013) by Robert Jordan (though the author died in 2007 and author and fan Brandon Sanderson was brought in to complete the series from Jordan’s notes), where the fourteen novels draw on numerous elements from both European and Asian mythology. A series that has become popularised due to its television adaptation by HBO is Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire into The Game of Thrones (1996-2012), which was inspired by the War of the Roses and Ivanhoe. It becomes interesting to examine these juggernaut creations of fantasy within the scope of fantastic history to see where they have drawn from and how it has been reinterpreted through a new lens.

Since the 1990s the genre has marked the rise of female-centric novels, with Laurell K. Hamilton’s Anita Blake, Vampire Hunter (1993-current) Urban Fantasy series being a notable example. This is only a tiny number of the significant pieces of the fantasy genre, an area of literature that boomed after the 1960s. As Timmerman pointed out in 1983 a ‘man’s thirst for “otherness” has sharpened in recent decades. A casual glance at booksellers’ lists will disclose the phenomenal surge in sales figures for fantasy works.’ 18 A statement that continues to be proven true today, especially due to the bestselling book series, J.K. Rowlings’ Harry Potter (1997-2007), which has allowed fantasy to become increasingly intertwined with mainstream fiction. All of these different influences have made fantasy today a multi-layered medium that encompasses a plethora of various subgenres.

It helps to understand how fantasy has developed throughout time and reflect on the complexity of its sources. Though not a comprehensive examination this indicates some of the important sources that the subgenres of fantasy have developed out of, since arguably many draws on elements of fairy tale, epic, romance, gothic, comic, as well as from a number of different mythological sources. To write in fantasy is not to be original in the truest sense of that word, but it is to be part of something larger. It is to be part of the stories that have shaped our world. It is to write on the backs of legends.

Where will your fantasy writing fit?

Works Cited

- Duffy, Maureen. (1972). The erotic world of faery. London: Hodder and Stoughton. p. 195 ↩

- Kratz, Dennis. ‘Development of the fantastic tradition through 1811. In N. Barron (1990). Fantasy literature: A reader’s guide. New York: Garland Publishing p. 32 ↩

- Rottensteiner, Franz. The Fantasy Book: The Ghostly, the Gothic, the Magical, the Uncanny. London: Thames and Hudson, 1978, p. 18 ↩

- Rabkin, Eric. The Fantastic in Literature. New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1977 ↩

- Donohue, Nanette Wargo. ‘The City Fantastic’. Library Journal. 133. 10 (Jun 2008): 64. ProQuest. 2 Jan 2015 ↩

- Moorcock, Michael. Wizardry and Wild Romance: A study of epic fantasy. London: Victor Gollancz Limited, 1988, p. 43 ↩

- Frank, Frederick S. The First Gothics: A Critical Guide to the English Gothic Novel. New York: Garland Publishing, 1987, pp. 435-7 ↩

- Green, Simon R. No Haven for the Guilty. London: Headline, 1990, p. 20 ↩

- Prickett, Stephen. ‘The Evolution of a Word’. Ed. David Sandner. Fantastic Literature: A Critical Reader. Connecticut: Greenwood Publishing Group Incorporated, 2004. 172-179, p. 173 ↩

- Wells, Carolyn. (2018). A nonsense anthology. CreateSpace Independent Publishing, p. 12. ↩

- Barton, Anna. (2019). Nonsense literature. Doi: 10.1093/OBO/9780199846719-0099 ↩

- Pringle, David Ed. The Ultimate Encyclopedia of Fantasy. London: Carlton Books Ltd., 1998, p. 28 ↩

- Waggoner, Diana. The Hills of Faraway: A Guide to Fantasy. New York: Atheneum, 1978 ↩

- Pringle, David Ed. The Ultimate Encyclopedia of Fantasy. London: Carlton Books Ltd., 1998 ↩

- Rottensteiner, Franz. The Fantasy Book: The Ghostly, the Gothic, the Magical, the Uncanny. London: Thames and Hudson, 1978 ↩

- Spivack, Charlotte. (1987). Merlin’s Daughters: Contemporary women writers of fantasy. Connecticut: Greenwood Press. p. 8 ↩

- Mendlesohn, Farah. (2008). Rhetorics of fantasy. Middletown: Wesleyan University Press ↩

- Timmerman, John H. Other Worlds: The Fantasy Genre. Ohio: Bowling Green University Popular Press, 1983, p. 2 ↩

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Excellent!! I really enjoyed reading this series.

Fantasy writers, remember the rule, which is, rules are meant to be broken.

Great article. While the mainstream idea of fantasy has always been the strand that followed from Tolkien, there’s always been that other side that was people like Harrison and Moorcock, and they in turn inspired people like Jeff Ford, Jeff VanderMeer, China Mieville, Zoran Zivkovic, etc. Meaning is in fantasy, you just have to look for it, same as any other genre I guess.

Around about 1999 I read a fantasy novel (in French but I believe this was translated from English), and I cannot recall anything like the title or the author. There were mentions of fractals, fever, a drug taken to fight the fever and responsible for hallucinations, experimental music… Does that ring a bell to anyone?

I think it was a childhood spent with Roald Dahl and Enid Blyton’s Faraway Tree that got me so hooked on fantasy – I love the way the genre at its best can combine the escapism of magical/alternate worlds while still being able to make intriguing comments on the human condition and big issues which ring true even outside the fantasy setting. Also love the sense of whimsy it allows.

The best fantasy ever, apart from Lovecraft, is ‘The Other Side’ by the austrian painter Alfred Kubin (1909), something which puts back the fear in horror and the fantasy in, well, fantasy.

I think my favourite writer of fantasy will always be Terry Pratchett as he had his serial world but with ever changing characters each book.

Re-reading many Pratchett books this year, on Going Postal at the moment.

What is it about fantasy/SF that means that authors seemingly can’t write normal length single novels? A good series is a wonderful thing, but most of the time I just want to read a complete work, without having to sign on for several books in order to find out the ending.

It’s the obligation that these kinds of stories place on the reader that’s occasionally galling. Like many, I’m a big Robin Hobb fan, but like many I’ve found stretches of the ‘Realm of the Elderlings’ to be more onerous than pleasurable.

More recently, after finishing the extant two thirds of Patrick Rothfuss’ masterful ‘Kingkiller Chronicles’, I picked up the first volume of Sanderson’s Stormlight Archive to try and scratch the itch for a while. About half way through I thought I’d check to see whether the next volume was out yet, only to find it’s been planned as a ten volume series. The fact that this filled me with more dread than anticipation speaks volumes, even though I am thoroughly enjoying the first instalment.

I much prefer set ups like Terry Pratchett’s Discworld: While it’s all one big world, each novel manages to somehow stand on its own and you can dive in and out as you like or smile when you come across familiar characters unexpectedly.

Many of the things that grew into huge franchises started out as one book/movie – Star Wars for example (okay okay, not really fantasy) was just one movie that could stand on its before it was expanded into a trilogy and went on to become the galactic behemoth it is now.

When a certain online bookstore jumps me with suggestions like “Book one in a planned series of seven” I shrink back, because I’m just not sure if I’m in for such a long ride. I admire writers who manage to tell a story in one book and then – if it’s successful and there’s demand – to build from there.

As for GRRM: I started reading the books after the first season of GoT and the more bloated the story became, the more I found myself skipping passages. Though I understand that virtually every reader has some characters/POV chapters he dislikes and others he adores and it’s different for each one.

The shadow of Tolkien still looms long over popular fantasy in terms of this obsession with multi-volume epics. It seems that any novelist wanting to be taken ‘seriously’ in the genre must at some point turn his or her attention to some 5,000 page monster of world-building and derring-do. Obviously the publishers, with their love of ongoing series, are happy to encourage this but I can’t help but feel that the authors, understandably keen to make a living from their work, often force this model onto stories that simply can’t handle it.

It feels like fantasy is long overdue its ‘punk’ moment — exciting young novelists who buck against the bloat. For all the claims that the various ‘grimdark’ novelists are shaking up the genre, many of them are still churching out epic series or stories set in the same world over and over again.

The size of these books just puts me off them entirely. Zelazny’s Amber series showed how it could be done – 5 short books that had little bloat in them and easy to read to boot. Admittedly he didn’t write another 5 but hey ho.

I recently enjoyed the first half of Catherynne Valente’s Orphan’s Tales (In The Night Garden – haven’t got to the second instalment yet). She’s re-telling those fireside folk tales in interesting new ways.

The amount of people who stick their nose up in the air as soon as you mention fantasy is astonishing. How can you not get caught up in the mythology of an alternate reality? You can probably tell from that last statement that I’m a Neil Gaiman fan.

It is a little sad that most people associate fantasy with ‘teen’ literature, and teen lit is fine – it certainly has its place (I read Twilight on a long train journey, for example), but the assumptions that stem from this means that people overlook the brilliance of more complex authors within that genre.

Twilight is not fantasy. Its not a traditional vampire story either, its a teen romance story, very different genre, just using traditional elements from fantasy and horror.

May I remind you all of the novels of Guy Gavriel Kay, from “The Fionovar Tapestry” and “Tigana” to “Sailing to Sarantium” and “Ysabel”. Set in historical periods mirroring those of our own world, they are highly engrossing and well written with fully realised characters and a total absence of the usual fantasy clichés.

Hmmm but what is fantasy when none are sure of what is fact? How can one tell if one has wandered past the border that separates truth from fiction?

As an aspiring writer myself I’ve endured much well-meaning advice along the “Why don’t you write a crappy fantasy series, how hard can it be?” line.

Suffice it to say, they have no idea how hard it can be.

I went through a long patch of not reading Fantasy, having grown up with the likes of David Eddings, Raymond E Feist , but they were all getting a bit generic, and many of them read like written up games, some more so than others, so I drifted away, but it was the Song of Ice and Fire series and the Lies of Locke Lamora (I’ll admit the follow up was a tad disappointing) that got me reading the genre again, as they seemed more gritty and there was an interesting feeling reading both of these that none of the characters were safe, which was an interesting developement in the storytelling.

It seems the Fantasy Genre has been rehabilitated over the past few decades, with The Lord of the Rings films, and the success of Game of Thrones. A novel I recently enjoyed tremendously was The Vorrh by Brian Catlin. Weird fiction, startlingly imaginative and original. I’ve always found most Fantasy fiction terribly derivative of Tolkien, who’s LOTR’s novels I’ve loved since my teen years, so something “fantasy” if it can be called that, like The Vorrh without Fairies, Wizards, Dragons or Ents and Elves, was delightfully refreshing.

I’ve just started reading The Vorrh, literally last night. It is indeed a very original novel.

I hope you enjoy it. It is the 1st in a trilogy.

I use to read a lot of fantasy especially when I was growing up when I was devouring all those Dragonlance and Forgotten Realms novels, a few of which I still rate highly even if most were rubbish in hindsight. I’d read everything by Eddings or Feist or Jordan but as I approached my 20s I drifted away from the genre (apart from Robert Jordan) as their new stories became rehashes of older stories. I moved on to reading more challenging science fiction, historical novels, real history and the occasional thriller.

I started coming back to fantasy with the rise of the authors adding a little more nuance to the good vs evil trope, a little more uncertainty as to who is and isn’t the hero. For me it probably started with G.R.R. Martin but since then I’ve been reading a lot of excellent fantasy (or grimdark fantasy as it’s being labelled now) by the likes of Joe Abercrombie, Scott Lynch, Mark Lawrence and Richard Morgan.

It’s Richard Morgan’s ‘A Land Fit For Heroes’ that has been my favourite of recent years. The novel revolves around three people who were heroes of a great war against the ‘Scaled Folk’ who, 9 years later, all find themselves pushing back against the societal chains trying to bind them; one the last of her race, greatly honoured for her heritage but alone and bound by duties she doesn’t want; another a barbarian of the Steppes, a great warrior amongst warriors who also happens to want nothing but for his own people to stop being brutal savages and become peaceful and civilised; and then there is Ringil Eskiath. Ringil is the greatest of the three, a highly educated noble, war leader and superb swordsman who is shunned and reviled by every nation (those who don’t just pretend he’s dead) after the war because he’s also openly and defiantly homosexual in a world where it’s a death sentence.

Ringil is one of the great anti-heroes of all time; cynical, cruel, cocky as hell and fundamentally a more decent person than 99% of the people he meets because he refuses to ignore the hypocrisies and everyday brutalities of ‘civilised society’.

A generation that’s grown up playing Dungeons & Dragons – and the other numberless and imaginative paper RPGs – hasn’t hurt fantasy writers at all, has it?

I loved the Harry Potter books, the films of Lord of the Rings and the Hobbit, and the Narnia Chronicles books and films, and am enjoying the series ‘Once Upon A Time’ on Netflix. I think that authors like JK Rowling, she in particular, have helped bring about the fantasy renaissance we’re currently witnessing.

I’ve never ventured into the Wheel of Time. I keep hearing bitter wails of disappointment from long term fans about how the series goes on. With the benefit of knowing the full series, is it worth reading?

Yes.

Check out Earlyworks Press for some really fine fantasy fiction.

Modern “fantasy” mostly derives from entertainment purposes due to volume of repetitions/releases and the expectations of modern audiences’ tastes accustomed to thinking in only these terms in books and films. Myths and such stories used to be tied much more coherently to their original cultures such as Halloween, Easter rituals throughout the year that more recent religions have co-opted working parts of these into their own narratives.

A taste for the weird combined with a creativity for the novel sustains a lot of the commercial demand of modern fantasy fare. An interesting comparison (although films) would be Twilight and Let The Right One In with the former very commercial and changing the thought process of vampires to satisfy base gratifications and the latter revealing something of the true nature of the concept of vampire in all it’s terrible and beautiful horror.

Science fiction and fantasy have long, long pedigrees in producing the very best stories. From the pages of magazines and short story collections (what fan, what author, doesn’t have at least a couple of issues of Galaxy, If or The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction?).

Good worldbuilding can take a novel. Great, incredible, unbelievable worldbuilding happens in serialised fiction, short stories, novellas. Stories that don’t need ten thousand words to explain the system of gods and dragons, myth and legend, but rely on characters – show, don’t tell and kill your darlings are the axioms of the writer for a reason.

The best fantasy novels – the real greats – are as often slim as they are novel-sized, and few of the truly amazing series continue being amazing after their first mega-novel.

I think if you grew up reading fantasy in the late eighties and nineties – or even the early noughties with their reprints of Magician, the Eddings’s magnum opus the Belgariad, endlessly multiplying (and terrible) Dune prequels – you’ll believe that fantasy can only be enormous. But the best science fiction, the best fantasy, is small. It blurs boundaries. It creates worlds and mythologies in sentences, because that takes skill, not just an idea.

“His followers called him Mahasamatman and said he was a god. He preferred to drop the Maha- and the -atman and called himself Sam. He never claimed to be a god, but then he never claimed not to be a god.”

Two sentences creates nearly all you need to know about a book so exquisite that the worldbuilding is left mostly to the reader, and one where you never quite know if it’s high Hindu fantasy or incredible science fiction.

Fantasy has edged out both hard SciFi and serious historical fiction.

There has been recently and perhaps still is a rather nasty controversy over sci-fi and fantasy in a writers’ organization devoted to those subjects. It appears to be between those who are interested in telling a rattling good tale and those who believe stories should be strained through a political correctness filter.

I think overall, I like fantasy trilogies.

Start, middle end with enough space to build a well rounded world.

In a world of Kindles where you literally distil a new book out of the air in seconds it has gotten very hard to keep track of some stories I read as you wait for the next book in a series (lots of great indy authors out there!) and a good trilogy is a great find as you know what you’re getting into from the start.

Ray Bradbury once said that to be good fantasy, it must first be good fiction.

Robert Jordan’s “Wheel of Time” series drove me away from fantasy. I just disliked being played for a fool, really. I think I managed three of them. The first was just about OK.

You gave up right before the best book in the WoT series. #4 is really very good. I almost didn’t get there because I hated #1, but my brother convinced me to keep going. Unfortunately, after #4 it just got worse and worse.

Von Ranke said that the best history is the best written history. The same goes for fantasy writing.

Prefer YA fantasy. Daughter of Smoke & Bone trilogy blew me away last year.

I’m a huge fan of fantasy (and sci-fi) and am glad both short “one-off” novels, massive door stoppers and sprawling, epic series exist. Sometimes I want a burst of Gemmell or Pratchett and at other times I settle in for the long haul with Hobb, Jordan et al.

A current favourite of mine is Joe Abercrombie – he set up his world with a trilogy then moved on to stand alone single books that keep building but also work on their own. His current trilogy, despite being pegged as YA, is also very good.

Patrick Rothfuss and Brandon Sanderson are also excellent, although sometimes I’m not sure if I prefer getting into a long series after its completed, or get more out of it when the books are gradually released every few years.

I believe that a writer of Fantasy must be judged on the basis of both quality of writing and world-building ability (or imagination, but of a particular kind). In my mind, an author like JRR Tolkien scores very highly on both criteria, as does GRR Martin. Robert Jordan scores about as highly in world-building as anyone who has ever lived, but his writing ability is mediocre at best.

I have to say that even though I know almost nothing about fantasy writing, the articles here are a consistent pleasure to read.

There are many excellent Fantasy writers now I’m very glad to say. But they come with a warning – you’ll probably find yourself impatient with the ‘midlife crisis/marriage breakdown mainstream writers after immersing yourself in the surprising, thought provoking, ‘what-if’ worlds of the best of the writers. In my 80s, I’m so grateful to them!

One of my favourites fantasy books is Lord of Light, by Roger Zelazny. Every bit as epic and well realised as LOTR, but it comes in at about 250 pages.

I know there are plenty of people who disagree with me, but I’ve always loved Madeleine L’Engle’s Time Quintet

This is a really cool descriptive history. I would love to know where you see modern genre-blending works like Butchers ‘The Dresden Files’ and the like fit in. You’ve given me a host of new books and authors to add to my reading list for this year!

I enjoy to read fantasy stories and watch fantasy movies/web series

What an amazing research work! Fantasy is one of my favourite genres in art and it was great to know more about it throught this article.

Very interesting post! I think that the next big thing in fantasy might come from today’s technologies: imagine a story like Gaiman’s “American Gods”, where fantasy meets internet and globalization, giving rise to new gods that eventually face the old ones. Expanding this idea, a new sub-genre of fantasy would be born.

I think this is a really interesting overview of the fantasy genre for those who have no idea about it!

Interesting to hear the offshoots that occur from these more mainstream genres/ writing styles. Connecting the gothic themes and scenarios to urban literature opened things up in my own thinking to some literature I have recently read and quite enjoyed. This piece makes me want to go back and re-read several books with this new found knowledge (lol).

This was the perfect posted for me! I’m currently working on my English degree, Creative and Professional Writing, and I don’t have a strong background in literature, let alone fantasy literature. With my background in Classics I can appreciate understanding influences and histories as they dictate far more than we give them credit for.