Time Travel: The Literary Way To Wander

The English author H. G. Wells inaugurated the time travel phenomenon, receiving nomination to the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1921, 1932, 1935, and 1946. The notion that humans can move forward into the future or move backward into the past by using a vehicle or other stationary equipment is attributable to his creative vision insomuch as it is through the domain of science. Since the publication of his 1895 book, The Time Machine, several films have been produced that further develop the time travel genre. In literature, the topic provides fertile ground for the motion picture industry to stretch the audience imagination. The film version of the Wells novel produced in 1960 debuted with an apparatus that resembled a Model T prototype. As the masses clamored for more, the movie industry responded in 1985 with Back to the Future, which revamped the chariot-like predecessor into a state-of-the-art DeLorean clad in stainless steel, to counteract those nerve-racking asteroids belts, no doubt. In no small measure, British composer Sir Arthur C. Clarke, explores the matter further by relating a vision of the future where space travel is the medium for a mission to spread intelligent beings throughout the solar system. The novel, 3001: The Final Odyssey, alludes to the science of tomorrow in a reference to astronaut Frank Poole. His frozen body is discovered beyond the orbit of Neptune and is resuscitated by advanced medicine.

Given the wide net of narrative angles, it is no wonder that the time travel story line has produced a deluge of books, movies, and television episodes. The films that form the basis for this particular brand of drama, have set the pattern for a series of critically acclaimed sequels. In consideration of the foregoing, the practicality of technological innovation will be examined as a measure of social, political, and philosophical progress by placing H. G. Wells in line with subsequent motion picture productions.

The film, Planet of the Apes (1968), recounts the dilemma of three astronauts who experience time dilation during a space mission. The dilation effect slows their aging process while the world they left behind has survived a cataclysmic evolution covering a span of 2,000 years. The planet has been re-inhabited by primates after a nuclear holocaust. The new primate order has constructed an Earthbound existence analogous to the human one predating the disaster. Their hierarchical dominance is culturally and intellectually advanced but remains burdened by the plight of the remaining human survivors who languish about the Earth. In one of the early scenes, the Charleston Heston character guides the audience through the state of mind required for travel through time as he grapples with the complexity of the journey.

George Taylor: And that completes my final report until we reach touchdown. We’re now on full automatic, in the hands of the computers. I have tucked my crew in for the long sleep and I’ll be joining them soon. In less than an hour, we’ll finish our sixth month out of Cape Kennedy. Six months in deep space – by our time, that is. According to Dr. Haslein’s theory of time, in a vehicle travelling nearly the speed of light, the Earth has aged nearly 700 years since we left it, while we’ve aged hardly at all. Maybe so. This much is probably true – the men who sent us on this journey are long since dead and gone. You who are reading me now are a different breed – I hope a better one. I leave the 20th century with no regrets. But one more thing – if anybody’s listening, that is. Nothing scientific. It’s purely personal. But seen from out here everything seems different. Time bends. Space is boundless. It squashes a man’s ego. I feel lonely. That’s about it. Tell me, though. Does man, that marvel of the universe, that glorious paradox who sent me to the stars, still make war against his brother? Keep his neighbor’s children starving?

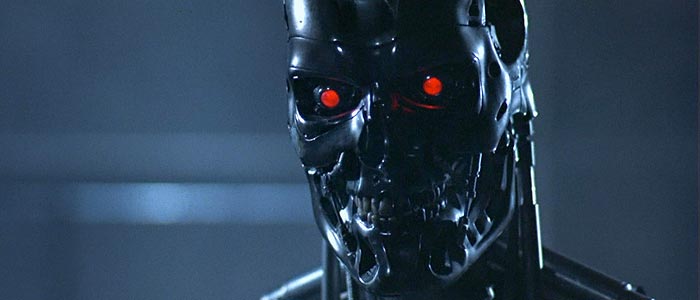

In, The Terminator (1984), the human race is once again locked in a battle for control of the future. A cyborg reenters the past by using a time displacement device. The device sends the cyborg and a human soldier into the past where they both seek to either protect or annihilate the birth of a yet unborn leader of the post-apocalyptic movement against cyborg combatants. The soldier sent back to maintain the sequence of historical events that establish his existence in the future, is ultimately confronted with the task of exposing his escape through a time continuum.

Dr. Peter Silberman: Why this elaborate scheme with the Terminator?

Kyle Reese: It had no choice. Their defense grid was smashed. We’d won. Taking out Connor then would make no difference. Skynet had to wipe out his entire existence!

Dr. Peter Silberman: Is that when you captured the lab complex and found the, uh, what was it called… the time displacement equipment?

Kyle Reese: That’s right. The Terminator had already gone through. Connor sent me to intercept him and they blew the whole place.

Dr. Peter Silberman: Well, how are you supposed to get back?

Kyle Reese: I can’t. Nobody goes home. Nobody else comes through. It’s just him – and me.[ . . . ]

Sarah Connor: What’s it like when you go through time?

Kyle Reese: White light. Pain. It’s like being born, maybe.

Altogether, humans have reached higher levels of innovation through technology but have not entirely achieved complete control over the inherent risks of technology. In the immediate context of these works, man has not fully eradicated the unpleasant realities of coexistence. As this screenwriter and novelist ascertain, the euphoria that emanates from technological alternatives, whether actual or virtual, remains subordinate to the irreconcilable social dilemmas of upheaval, famine, and injustice that persist. Indeed, time travel may only confound the challenges imposed upon future civilizations. The first contention is explained by the Twin Paradox which basically holds that a person who remains on Earth while his twin is transported away from Earth on a spacecraft traveling about the speed of light will age faster than the traveling twin, by undergoing a disproportionate aging process. This is part and parcel to the effect, though The Planet of the Apes raises it a notch higher by showing that time travel can bring forth a more treacherous tidal wave of complications over what is deemed rational and natural. The second contention, and most mind jarring one, is the Grandfather Paradox which ponders the consequence of traveling back to the point of your grandfather’s age just prior to his marriage, using that situation to prevent the birth of your father and, hence, blocking your own life from ever becoming a reality.

This way of thinking about time dimension, as viewed in The Terminator, can justifiably lead to an infinite number of probable situations; which in turn, reveal the mushrooming effect of time flow, were we to eventually harness its power or potential. In 2001: A Space Odyssey, both paradoxes are interwoven throughout the movie sequence. The film begins with a scene from prehistoric times where apes are seen bearing bones as tools and weapons. Later in the film, there is a scene of an astronaut who ages instantly from one second to the next during a space mission. The film ends by showing Jupiter and a fetus side by side within the picture frame. This sequence of events can set into motion a typical Causality Dilemma. When the first and third scenes are switched around, the fetus first and the apes last, it doesn’t make sense chronologically, within the running theme of the film. This is notable since a fetus is generally considered to be the initial point of life, yet, other screen portrayals set the origin of life by an ape civilization. On the simplest level, time travel may amount to nothing more than a time capsule headed on a fateful mission to oblivion.

Whether by personal affinity or by cinematic-based premonition, the reading of imaginary worlds is taken with disapproval by some students, unfathomable riches by other students with a keen sense for creativity and artistry. In literature, these types of novels constitute a source of entertainment that can justifiably serve to enrich the intellect of the reader and, ultimately, the audience at large. The context is often simplistic enough to aid the reader in readjusting their current situation for reassessment of direction or as a basis for forward action. Through the narrative, the plot twists and turns can provide alternative recourse when the modern outlook is dismal, stagnant, or altogether nonexistent. In other contexts, the intricacy is so thorough and plausible that true fans admire the text for its remarkable detail in relating the unthinkable in a way that would eventually become the mainstay of reality.

In this examination of prolific composition, a symbiotic question arises in light of the practicality of the novel for setting forth a lifestyle replete with considerable innovation and undiluted vision. Do literary accounts of historic events counteract or elevate social, political, or scientific outcomes? To kindle the response, it is necessary to be mindful of the magnanimous verse of the English poet William Blake, “What is now proved was once, only imagin’d.”

In terms of the works envisioned by George Orwell, it seems that literary tales transform the notion of actual into ensuing scientific or social agendas. In the novel, 1984, Orwell proposes a bleak version of the future and its implication on the vital stance of individual privacy; not to mention, the preconceived role of political institutions vis-à-vis bureaucratic affiliations against individual prerogative, whether legitimate or rogue, self-serving or messianic. The challenges inherent in the eventual onslaught of invention and subsequent distribution of resources, are only a few insights garnered in the 1949 narrative that proved to be prophetic in many areas of modern life.

To further this preoccupation with the challenge or plight or promise of tomorrow, French novelist Jules Verne depicted a substantial list of inventions that appeared untenable in skeptical minds; albeit, long overdue by more optimistic supporters. Verne authored six fictional novels: Journey to the Center of the Earth (1864), From The Earth to the Moon (1865), Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea (1870), Around the World in Eighty Days (1873), and Robur the Conqueror (1886). These works, in one form or another, predated the invention of the submarine, the helicopter, the modern city, and Moon exploration. By comparison, Wells provided for the possibility of time travel by conjuring the thought along with the apparatus, perhaps lackadaisically, Verne only envisioned time travel up to and including the Moon, despite a commendable attempt at the necessary apparatus. Yet, the significance of Verne’s foray into the world of tomorrow lies in the longing for a continuance of the impetus stemming from his work and inspiration. In order to reap the rewards of time travel, the unenviable courage and foresight of authors such as Verne must be reread at the onset of each and every new generation of visionary inventors and leaders. For the time being, audiences will have to delight in the silver screen brand of travel, whether through air, space or even water. For that, cinema has weighed in with their design, a Lotus Esprit with a submarine option in The Spy Who Loved Me (1977).

Most literary works rely on layered interpretation of plot, character, or setting to develop the story line. In the realm of science fiction, the matter can conceivably take on a more pronounced and intricate structure of reasoning, due in part, to the underpinning of science or merely by the creative stream of the author.

This point in the matter begins by selecting a screenplay and exploring the underlying philosophical context implied within the character interaction and plot elements. The dialogue noted henceforth is referenced from the television series Star Trek that aired publicly from 1966 to 1969.

By far, the most prevalent allusion in the Star Trek episode “All Our Yesterdays” is with the Allegory Of The Cave in Book VII of The Republic by Plato. The cave is a metaphor for man’s ignorance and hence his condition of being a prisoner to that ignorance, being unaware of a world of possibilities beyond the confines of the cave walls. Zarabeth and Spock both allude to Plato’s notion of imprisonment by revealing the event leading to their presence in the cave and their destiny, were they to remain. In this prehistoric setting, love is the only escape from the bitterness of isolation and desperation. Spock’s regression from highly civilized to irrepressibly barbaric is proof to this dilemma. As an aside, the cave takes on further symbolism as the Garden of Eden, where Eve (Zarabeth) is tempered by Satan (Spock) as Adam (McCoy) stands witness.

SPOCK: It is agreeably warm here.

ZARABETH: What are you called?

SPOCK: I’m called Spock.

ZARABETH: Even your name is strange. Forgive me. I’ve never seen anyone who looks like you. Why are you here? Are you prisoners too?

SPOCK: Prisoners?

ZARABETH: This is one of the places Zor Kahn sends people when he wants them to disappear. Didn’t you come in through the time portal?

SPOCK: Yes, we came through the time portal, but not as prisoners. We were sent here by mistake.

ZARABETH: The Atavachron is far away, but I think you come from someplace farther than that.

SPOCK: That is true. I am not from the world you know at all. My home is a planet millions of light years away.

ZARABETH: Oh, how wonderful! I’ve always loved books about such possibilities. But they are only stories. This isn’t real. I must be imagining all this. I’m going mad!

SPOCK: Listen. I am firmly convinced that I do exist. I am substantial. You are not imagining this.

ZARABETH: Oh, I’ve been here for so long, alone. When I saw you out there, I couldn’t believe it.[ … ]

CONSTABLE: Where are you from?

KIRK: An island.

CONSTABLE: What is this island?

KIRK: It’s called Earth.

CONSTABLE: I know no island Earth.

In the medieval portion of the episode, Kirk’s incarceration for witchery is another allusion to Plato’s cave analogy. Once again, it is by man’s unsound perception of evil that lands Kirk in a jail cell. It is only through Kirk’s innate reasoning (and brawn) that he is able to convince the Inquisitor to release him and facilitate his return to the future, in Kirk’s case; a stark contrast to the dungeon quarters presumably replete with spirits in hiding.

Within the portions of the episode as set forth by the futuristic setting of the library, the perception of reality reaches full circle. The library holds the sum total of existence and is maneuvered by none other than three versions of the same man, Atoz, a slight inference to the Holy Trinity. In Plato, there is the notion of a puppet-master pulling the strings of reality. In essence, an omniscient (albeit compassionate) force that can only expect so much in return from a cowardly underling that can’t see past the lines of the shadows on the cave wall.

In the end, the overwhelming plea is to confront your cavernous plight and transcend it through spiritual or intellectual alternatives–within the eternal struggle, enlightenment prevails. As a final note, some ploys can be interpreted as foreshadowing moral decay. The first one is the meat offering between Zarabeth and Spock. Another is the reference to ‘spirits’ as a connotation to the perils of imbibing. Not least of which remains, the destructive influence of technology upon the delicate fabric of humanity. A matter to contend with since Star Trek was not the only television examination of time travel insofar as its objective, its method, nor its benefit, if any, are concerned. A television series that aired following World War II in the years 1954 to 1955 , made its own mark on the elusive time travel phenomenon. In the Flash Gordon episode “Deadline at Noon”, the protagonist Flash Gordon attempts a time transition from the year 3203 backward to the Berlin of 1953 using a portable time shifting device. The show characters, Flash, Dale and Dr. Zarkov make the time leap using a spaceship in service of the Galactic Bureau of Investigation. This backdrop of war-torn Germany, may well have led to the induction of Flash Gordon into the US National Film Registry for relating a pivotal moment in human history.

Lastly, in the scene between Kirk to Atoz the preoccupation with thwarting the essence of time through devices of dissipation is revisited as shown by the glacial pace of human progress in relation to the imminent pace of the universe, as it were, a star’s impending evolution into a state of supernova.

ATOZ: May I help you? You may select from more than twenty thousand verism tapes, several hundred of which have only recently been added to the collection. I’m sure you’ll find something here that pleases you. You, sir, what is your particular field of interest?

KIRK: What about recent history?

ATOZ: Really? Oh, that’s too bad. We have so little on recent history. There was no demand for it.

In such circumstances, being confined to a barren desert, marooned on an island at sea, or having to experience reality through a diminishing aperture, creates ripe conditions for time travel, to quell the stifling sensation of monotony to some degree. To that effect, the title of the episode is derived from Shakespeare’s Macbeth during a soliloquy in Act V Scene V that remarks:

And all our yesterdays have lighted fools

The way to dusty death.

Here, the underlying implication perhaps being that from dust he emerges and to dust shall he return; man’s only elixir in light of his predicament is the illusion flowing from dreams or memories of the past notwithstanding future deferments, fleeting as they may be. On an even more superficial level, the episode lends itself to commentary on the human psyche in terms of personality disorder. Spock begins to transform to a more primal version of the Vulcan identity as the plot develops. There are three impersonations of Atoz which confound the story in a manner not too far removed from a multiple personality complex. As well, the medieval spectacle encountered by Kirk is littered with delusions that: spirits abound.

However whimsical the latter, the relevancy of this epic objective has been entrenched in science fiction circles. In 1955, Jack Finney writes about plant matter traversing through the cosmic layers of the universe, taking root in planetary ecosystems, and thwarting mankind; only to be conspicuously whisked away to ever more distantly protruding points and predicaments. This is best conveyed in an essay by Robert Skylar in reference to the 1956 film version of the Finney novel.

“Invasion of the Body Snatchers” arrived as part of an explosion of science fantasy and science horror in mainstream popular culture, fueled by the atomic age, advent of space rocketry, and Cold War anxieties. “So much has been discovered these past few years that anything is possible,” say Dr. Miles Bennell (Kevin McCarthy) after he discovers that mysterious seed pods grow into human forms and take over actual persons, retaining their former physical characteristics but completely transforming their personalities. “It may be the results of atomic radiation on plant life, or animal life … some weird, alien organism … a mutation of some kind.” Once a pod is ready to become you, the moment you fall asleep you’re a goner.

In view of this, the film’s implication and the novel’s timeliness have both succeeded in resounding certain publicity to the point that it was inducted to the US National Film Registry by the Library of Congress for its allegorical perception of 1950s America. In The Body Snatchers, Finney addresses the probability of plant-based reinsurgency over the natural order; a tenable notion considering the fact that dinosaurs once reigned over all species, until their untimely and inexplicable demise. The 1978 film adaptation of the novel Invasion of the Body Snatchers, brought home the vulnerability of civilization, not merely so much by human deed, but by the potentially mutinous botanical variety. The Finney novel mangles the social order on the cosmic level, incisively; marginalizing the technological factor as highlighted in this undertaking.

This leaves open the question: given the likelihood of time travel, would mankind remain coherent, distinguishable, or existentially viable across time and space, where ever that may manifest thinly and delicately as proposed? The answer to that may well lie in the camp that has encouraged the dystopian theme: theater. In Blade Runner (1982), the future is reimagined as a setting where human survival is cosmically vetted through genetically engineered replicas conceived primarily for the unfathomable exploration and exploitation of the universe. After a substantial experience at the farthest corner of the universe, the human replicas inexplicably return to Earth to reintegrate themselves into the mainstream: some peacefully, some deviously. In the final scene, actor Rutger Hauer goes against the grain by rescuing his captor from a rooftop confrontation; in a last effort to defeat mortality and in an ironic lament to his misgiving.

I’ve seen things you people wouldn’t believe.

Attack ships on fire off the shoulder of Orion.

I watched c-beams glitter in the dark near the Tannhäuser Gate.

All those moments will be lost in time, like tears in rain.

The actor is conveying, in part, the logistical challenges of time travel using a reference to c-beams which are a type of particle beam that are accelerated to levels near the speed of light. They are recognized as cutter beams; cesium beams by scientific denotation; or as abbreviated. In practice, a glitter effect is produced when agitated C55 isotopes reach the contact point of a starship hull, effectively slicing it apart. The glitter pattern is the close range aftershock of defense shields formed by clusters of granulated substance that react explosively with starship material. This occurs upon impact from an energy-prone weapon or by straying into a space minefield. Being in the presence of c-beams glittering simply means that either you are the aggressor or you are the target at close proximity. In space combat, the Tannhäuser Gate would be the ideal zone for sighting this effect. This is because there is an adequate concentration of hydrogen to dither the beam path. A feat that is not otherwise possible since, lasers included, c-beams do not travel at the necessary right angles.

Along those same lines, this scenario raises the concern of what would be waiting at the end point of time travel. Any such destination might be dominated by an animal species that succeeded in collaboratively inhabiting the colony as in Planet Of The Apes, a natural species or an artificial one like in Blade Runner. It may be replete with a plant species that already exists in outer space and that could harbor life by suppressing emotions and continuously spawning human life, as depicted by Invasion Of The Body Snatchers. A civilization that is permeated by an advanced phase of survival technology with little tolerance for humans could be just another of the many possible worlds that await in outer space, similar to that of The Terminator. Regardless of the destination or its inhabitants, the experience would inevitably prove to be an utterly moving quest. If nothing else, time travel stands as a constant reminder of the dystopian condition of man’s eternal struggle for breaking Earthly bounds in order to reach the distant gates of a heaven beyond.

Apart from the creative impact of these works of art, all three films have the added distinction of being among those selected for preservation into the US National Film Registry for contributing to the voicing of “culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant” trends in government and industry. This honor is bestowed upon by the Library of Congress whose main purpose is to promote literacy and American Literature through repositories such as the American Folklife Center and the American Memory. The role of television in this public endeavor is further indicated by the existence of works such as the Flash Gordon series in those repositories. No less commendable is the fact that there is also a considerable presence of the original Star Trek series within in the arena of scholarly research.

By this consideration of cosmic colonization, it goes without saying that the film version of the Wells novel has been duly established, but; later motion picture renditions of the concept play more broadly on the intermingling of outer space within the galactic infrastructure belying the time portal effect. In particular, the film industry has competently seared the manifestations of human transformation through time elasticity on multiple levels. It has justifiably provided some glimmer of hope for universal peace despite indications of savagery and constant, if hypothetical, annihilation wrought by machines, or plants for that matter. In contrast to earlier cinematic narratives, the modern versions have added a measure of intrigue and fascination through special effects, greater sensory immersion, and philosophical dimension.

Though some may differ in opinion, the science fiction that is represented by the time travel mystique is part and parcel of the human condition, restless and listless as it may be. One need only be reminded of the historical aspirations of the political leadership that threatened to keep humanity in line, as it were, through the atomic bomb and the Strategic Defense Initiative, among others. Within the context of Wells and Verne, the inventive capacity is optimal where and when machines facilitate and amplify the limitations of man and beast alike, but become disconcerting when systematic eradication of life is only the push of a button away, so to speak. Idealistically, some annals of thought have been more empathetic when dealing with the promise of technological progress. The Gene Roddenberry series has shown a generation of television viewers that amidst all the technology that awaits, one must never lose sight of the overbearing desire and provision for ultimate peace and harmony throughout the universe and across the spectrum of time–for all walks of life.

Another viewpoint places the time travel impulse into perspective by revealing just how far we have to go before reaching the outer banks of the universe. In a speech by astronomer Carl Sagan, he relates to audiences the immense trajectory that befalls mankind in the race for discovery of extraterrestrial life and intergalactic transport.

That’s here. That’s home. That’s us. On it, everyone you love, everyone you know, everyone you have ever heard of, every human being who ever was, lived out their lives…[E]very king and peasant, every young couple in love, every mother and father, hopeful child, inventor and explorer, every revered teacher of morals, every corrupt politician, every superstar, every supreme leader, every saint and sinner in the history of our species lived there–on a mote of dust suspended in a sunbeam.

The Library of Congress has preserved Sagan’s contribution to planetary studies beginning with his past as a student at the University of Chicago and as a professor at Harvard University and Cornell University through an extensive archive containing notes, letters, and speeches. The Sagan files represent a vast body of work regarding the ecosystems in space as much as a solemn reflection of our minuscule role in the universe.

There is a wide yawning black infinity. In every direction the extension is endless, the sensation of depth is overwhelming. And the darkness is immortal. Where light exists, it is pure, blazing, fierce; but light exists almost nowhere, and the blackness itself is also pure and blazing and fierce. But most of all, there is very nearly nothing in the dark; except for little bits here and there, often associated with the light, this infinite receptacle is empty.

This picture is strangely frightening. It should be familiar. It is our universe.

Even these stars, which seem so numerous, are, as sand, as dust, or less than dust, in the enormity of the space in which there is nothing. Nothing! We are not without empathetic terror when we open Pascal’s Pensées and read, “I am the great silent spaces between worlds.”

Even if only as a tribute to Sagan’s memory, supporters remain in awe toward what lies beyond and when the time will come to experience it firsthand, in its entirety. In March 2014, Joel Achenbach writes in the Smithsonian Magazine on the unrelenting imagination and steadfast optimism that Sagan held in his vision and quest for man’s eventual sovereignty in outer space by way of a time continuum.

In late 2013 scientists announced that based on extrapolations of data from NASA’s Kepler Space Telescope, which scrutinized a tiny patch of the sky, there may be as many as 40 billion planets that are roughly the size of the Earth and in orbits around their parent stars that put them in what we consider to be the “habitable zone.” Even if the Kepler-data extrapolation is off by an order of magnitude, or two orders, that leaves an astonishing amount of apparently life-friendly real estate in the Milky Way galaxy—which is, of course, just one of, yes, billions and billions of galaxies.

A 1841 Norwegian folktale by Jørgen Moe and Peter Christen Asbjørnsen reminds us how indelible time travel remains within the human spirit. (Note: shoon is a shoe, bairns are children.)

‘Then they built themselves houses,

And stitched themselves shoon,

And had so many bairns

They reached up to the moon.’

In the final analysis, the aforementioned novelists and screenwriters have reinvigorated attention to the possibility and inevitability of time travel to the dismay of skeptical audiences and to the complacency of sympathetic ones. The destination would undoubtedly require some amount or form of acclimation upon arrival. Assuming that time travel was survivable, it presumes that there would be an immense environment that would have to be tamed in order to settle. That activity would only mire the fact that any such settlement would eventually be further strained by feelings of nostalgia for Earth, as we once knew it. The overbearing question, if at all, is what would we do if the backward destination was irrepressibly lagging and arcane in terms of progress or what would we do if the forward destination was prohibitively advanced to the point of incomprehensible or intangible, and would time travel unexpectedly reconstitute the present in an aesthetically pleasing light? Only time will tell.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

In “All Our Yesterdays”, I’m going to go with the time portal being a technology so different from ours it’s like magic. When I stop trying to figure out how it works and just try to understand what it’s doing, it makes sense.

So, this is a time travel system that allows time travel but does it without changing the past. Somehow, the people are literally altered to fit into the periods they go to and, through some means we don’t understand, this alteration also keeps them from changing the past in significant ways. Part of the alteration is done by the portal. This is why Spock begins to change once he goes through. But, there are steps that need to be taken to complete or stabilize this change.

I think we can assume this stabilization allows a person to fit into the past in some way as well. Hence, one traveler has become a magistrate in a period that’s very like our renaissance, something that would have been hard to do in our version without a known background and family.

Kirk, on the other hand, can’t last five minutes before he’s a walking anachronism on trial for witchcraft. Granted, he’s Kirk. That’s what we expect of him. But, still.

I like this episode, despite its flaws.

Travel through time has been a popular plot device in fiction since at least the 19th Century.

The first book that introduced me to time travel is ‘A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court’ by Twain. I think it is one of the first to revolve around the idea of a character from the future introducing his knowledge and technology to a past civilization.

I like how A Christmas Carol is indeed a time travel story. Scrooge travels through space and time, visiting both his past and his future.

Storytellers tend to mix up the narrative time with the actual flow of time in the universe.

A fascinating article and a damned good read. Thank you. Thanks also for confirming my suspicions that the ‘c-beams’ mentioned by Roy in ‘Blade Runner’ were indeed Caesium beams. I’m glad to see that you didn’t get bogged down in the ‘Grandfather Paradox’, so beloved by some writers. A much over explored idea, in my opinion. I liked how you have drawn from a wide variety of sources. This helped to keep me interested and keen to read the whole article. Thank you for your time, research and effort.

All Our Yesterdays was the very first episode of Star Trek I ever saw, and I was absolutely hooked by the Spock/McCoy interplay; it’s probably safe to say that I was a Spock fan first and a Star Trek fan second. It’s still one of my favourite episodes, despite the gaps in logic, and its two prose sequels are among my favourite Trek books as well.

I loved this episode. it was my second favorite of the season, after “The Paradise Syndrome”.

I don’t like this episode as much as everybody else does. I find it bland. Perhaps it’s because I’ve read Nimoy’s books before I watched it – he complains that the writers wrote a love story for Spock without considering that Vulcans don’t fall in love like that, and that they added the rather nonsensical explanation only after he pointed this out to them – but to me it feels as if Nimoy is mostly annoyed that he has to play being in love with Zarabeth.

We’ve seen several types of time travel in Dr. Who, and some of them are less perfected and more prone to error than much else.

While the best known of all books about time travel is The Time Machine, the idea, albeit couched in less scientific terms, goes much further back.

Recommending “By His Bootstraps,” Robert A. Heinlein. It is a short story dealign with the topic of time travel.

If we are doing recommendations, mine is The Time Traveler’s Wife, both the book and the film.

Slaughterhouse Five, Kurt Vonnegut, 1972.

Great post. Helped me to understand how all this time-travel jiggery-pokery works.

I like how in the Planet of the Apes movies, time travel comes in around the third movie or so, which causes the curious effect of having a series that ends right where it started, and where the last couple movies are actually both prequels and sequels to the first films—at the same time.

In 2001: A Space Odyssey, it is not time travel. It starts in the remote past, then the moon, then the voyage to the monolith. Bowman’s transformation does seem to have him see successive future stages of himself. This is not really explained. There is a great book by Clarke, The Lost Worlds of 2001, explaining the logic behind the film and book.

All of the different ways those fictional mortals manage to thrust themselves back and forth in space-time… 🙂

It is interesting in Back to the Future when you see the photograph changing because of something that happened in the past. That doesn’t make sense in anyone’s version of anything. I mean, what is right now? Why is it changing now? What is this supposed to be? It’s something that happened years in the past! It’s clearly a mixed-up attempt to change the past and yet only have one timeline. That would not make sense.

The most shocking thing that one can discover about Planet of the Apes is that it is serious.

Time travel has been one of cinema’s most reliable plot devices.

Time travel is so cool. More people need to write about it

I learned so much!

Although “All Our Yesterdays” was the first TOS episode I saw, at around age 10, I managed to completely drop Kirk’s trip into the past from my memory. In my mind, for 25+ years, this episode only had Spock and McCoy in the past.

Anyone read Outlander by Gabaldon?

Creative time traveling thought… I went forward in time yesterday by 24 hours, and here I am.

There are hundreds of novels and short stories about or involving time travel, but my favorite is “How to Live Safely in a Science Fictional Universe” by Charles Yu.

I believe that, in the T1 movie they of course change the future, not enough to prevent war, but to change how machines are built (technology from the future trapped in past used to build better machines) so that’s why we see how in T2 movie the Terminator is way better and evolved than T-400.

Nice job, well-written. Many novels/films use time-travel for political analysis. Check the novel Moscow 2042 by Voinovich. Also, some episodes of Twilight Zone deal with the topic

Very interesting! The Time Machine of H. G. Wells is one of my favourite books.

One of my favorite and especially geeky bits of Trek trivia relates to the ‘All Our Yesterdays’ episode. The sound effect used for the Atavachron was the IRIG-B time code transmitted by standard time and frequency stations WWV/WWVH back in the 1960s. (The format has since changed.) A time code sound effect always seemed highly appropriate for a time machine.

Stephen King’s new work, 11/22/63, comes into mind. It’s a novel about a man who travels back in time via a storeroom to stop the JFK assassination,

This is not the first novel to deal with the JFK assassination via time travel, it sure is a good one.

You can invent an idea that’s not based in physics, or anything we know about the laws of nature, but you could invent an idea that is sort of like fixed points in the future. There are choices that we have now. Different things could happen. But no matter what we do now, there’s going to be some ultimate outcome.

In common time travel plots in science fiction, there is one time-line, but time travelers can change the timeline by going back and changing events from what had occurred before they travel back. Doing so makes the previously-established timeline exist only in the memories and stories of the time travelers.

“The likelihood of time travel”?

Is about the same as the likelihood that a loving and all-powerful god exists.

Its just a matter of time. Time travel will become a reality.

A great discussion, I would liked to have seen you extend this to Dr. Who as really that is perhaps the best example of a wanderer – less driven by narrative and more by the desire to explore. I love HG Wells and his time travel texts, I think also some of the same appeal is present when authors write of immortal beings, such as Simone de Beauviors ‘All Men Are Mortal’, and many of the Anne Rice novels – we innately appear to have a fascination with any time other than our own.

Interesting bit about the National Film Registry. Time travel is certainly a unique facet of human wanderlust.

I wonder what you think about more philosophical time travel. For instance, in the novel A Tale for the Time Being by Ruth Ozeki, one of the characters “travels” in time by writing a diary in the past. That is to say, her words keep her alive in the present (to the diary reader) while all indications seem to point that she died in the past.

If a living memory constitutes time travel, I wonder what that says about The Time Machine – and the other works you have mentioned. You’re writing about them, so maybe they have found a place in the future.

I didn’t even consider this with Blade Runner and his statement at the end of the movie–the improvisation of that shows just how meaningful that movie was. I wonder how that applies to 2049.

A lot of Futurama episodes/movies also had some pretty interesting, unique, and highly scientific approaches to time travel.

One of Futurama’s best episodes is about time travel. It’s also the one that won it an Emmy. “Roswell that Ends Well”

I enjoyed your discussion of how there can be different possible scenarios through time travel. There’s a show called ‘Timeless’ that explores the problems you could cause by changing the past. The heroes try and stop a man who wants to change the past but ultimately just be being there, they always change something.

‘Behold the Man’ and ‘A Sound of Thunder’ are favorite time traveling novels of mine. The former is interesting in that the protagonist, Karl, goes back to visit the time of Jesus, only to find out the Son of God is a mentally-challenged fool and his mother, Mary, is a prostitute having delusions of an angel impregnating her. Karl then uses his knowledge of science to cure various peoples’ diseases and begins preaching the gospel properly as it is known in his time. He becomes popular throughout the Holy Land, leads the disciplines, and tells Judas to betray him to the Romans. He completes the story of Jesus to the end when he is crucified.

Hi this is going to sound crazy but I do believe that time travel is a real thing and that in due time we will discover it. The reason why I do believe it in so strongly is the fact that there are so many strange disappearances that no one can explain, on saying this I have not heard of any strange appearances (except on YouTube). I just think that it does pay to have an open mind about it.

Good article!

As a personal devotee of the time-travel subgenre, I love the way this article was not only fun to read but also insightful about the interaction between literary/cinematic creators and their audiences. My favorite insight in this article was how these works of art allow us as readers and viewers to imaginatively travel beyond the arrow of time imposed by our acquiescence to Einsteinian relativity and live, for the duration of the artistic moment, in some alternate time. In that sense, which this article alludes to, we break those bindings of space-time laws to experience greater lessons to be learned by a wider spectrum of human experience. Time-travel *is* possible, if only through our imaginations, and the trappings of logistics are sometimes express while others times merely implied. If the story’s well told, our desire to participate in these fanciful excursions allows us to forgive and surrender to our willing suspension of disbelief in a way that doesn’t differ whether the story is set in the past, the future, or some alternating combination along the continuum.

Thank you for an entertaining and thought-provoking article about the way humanity overcomes, for now, time-bound realities. Imaginative experience feels no less real (we need but notice the rate of our own heartbeat or the increased infusion of adrenaline brought about by a well-executed story) for these “made-up” stories to transport is to other times.

This makes for an interesting read. I like how you captured a number of source material but I am left wondering what you might hint at as a ‘stone left unturned’ for the science fiction genre when it comes to time travel. Whether possible or not, time travel definitely impired by our want to be agents with control over our past, as we do our future. Yet science fiction material predominately deals with the negative consequence of time travel. Does this tell us something interesting about how we view ourselves?

Beyond technological curiosity, our fascination with time travel reveals our human fear of uncertainty and a frequent, nagging sense of regret. Thoughts along the lines of “If only I could go back” and “What would happen if this or that didn’t” step out of the realm of mere hypothesis in scenarios where time travel is possible. We seem to be ill at ease with determinism and so continuously think up stories in which we can alter the course of our lives. What’s interesting, I think, is that in most of these stories in the end our fate remains beyond control—another great cinematic example that comes to mind is Donnie Darko by Richard Kelly.

What we can control however is our reaction to technological progress and whether or not social and political development follow suit.

I also always felt that it was in the genre of science fiction and often time travel specifically where writers really began to play with non-linear storytelling, which has of course now spread across all genres

Time travel is such an exciting notion. I always say it would be my super power if I could chose one. In science fiction, the artist grapples with the effects of technology which scientists and politicians refuse to consider. The Romance genre also loves time travel as evidenced by the Outlander Series and many more novels with the same premise.

In many ways, H.G. Wells was not simply the father of the time travel genre; he was the father for all of Science Fiction.