Demystifying Franz Kafka

Franz Kafka, the early 20th-century Jewish humorist, is one of the most studied and admired writers of his era. At the same time, he is also one of the most misunderstood.

Interpretations of his stories, and his personal life, are legion, but many overlook crucial details or make things more complicated than they need to be. The truth is that Kafka’s writings are both much more accessible, and a lot more relevant to people’s everyday lives, than many realize.

Kafka’s Life and Times

Franz Kafka was born into a middle-class Jewish family in the city of Prague. This city, which is located in the modern Czech Republic, has a long and illustrious Jewish history. According to legend, a fourteenth-century rabbi from Prague, popularly known as the Maharal, created a monster called the Golem to protect his community from anti-Semitic attacks. 1 Regardless, Kafka’s family was not religious, and attended synagogue services only a few times a year. His father, Hermann, was a successful entrepreneur who ran a haberdashery shop with the help of his wife, Julie. 2 Young Franz also had two brothers–who died in infancy–and three sisters: Elli, Valli, and Ottla.

Kafka’s childhood was not a happy one. His father was intensely narcissistic and abusive, and his mother, though well-intentioned, was often emotionally distant and neglectful. 3 Kafka recalls, in his autobiographical Letter to His Father, that once when he cried for water as a young boy, his father responded by locking him outside of the apartment in the middle of the night. He also writes of going swimming, and particularly undressing, in front of his father with such horror as to suggest that his father might have sexually abused him in some way during those occasions. Moreover, since both of his parents worked long hours, Kafka and his sisters were largely brought up by the family servants. 4

Although Kafka’s father wanted him to take over the family business, Kafka instead decided to go to university and study law. 5 He held jobs at various insurance agencies, where he helped reduce workplace accidents. This job provided him with a steady income, but he disliked the fact that it took time away from his writing. 6

Kafka himself never married or had children, though his three sisters did. 7 He died in 1924 of laryngeal tuberculosis, not long before the Nazis came to power. Most of Kafka’s remaining family would perish in the Holocaust. Some of his nieces survived, as did his friend Max Brod and his then-girlfriend Dora Diamant. Brod, a writer in his own right who introduced the world to many of Kafka’s most famous works, died in 1968 in Tel Aviv. 8 Diamant, meanwhile, who never found another partner after Kafka, died in London. 9

In Letter to his Father, Kafka speculates that he and his family members each had fundamental, unchanging natures, and that he therefore always would have been weak and anxious. However, this is almost certainly not true. Researchers nowadays believe that sensitive people (as Kafka was) are highly influenced by their formative environment, for better or for worse. 10 As such, had Kafka been raised in a more loving and supportive family, he very likely would have become a completely different sort of person.

Kafka’s Mental Health

Kafka’s mental health was poor for most of his life, although exactly how ill he was, and in what ways, is a matter of some debate. Some of the confusion likely lies with Kafka himself, who was not a very good self-observer. For instance, he was convinced that he was loathsome and unlovable, even though he had many friends and lovers who really liked him! 11

In any event, it is clear that Kafka suffered from depression and anxiety for many years, and many of his stories dwell almost obsessively on alienation, suicide, self-harm, and murder. Of particular note is his short story The Burrow, in which an obsessive-compulsive animal of indeterminate species builds an enormous, labyrinthine burrow in which he can live sheltered from his enemies. When the animal discovers a whistling sound in his burrow that he cannot account for, he completely loses his mind with fear that he has been discovered by a predator. Even the fact that the whistling does not sound like a digging animal brings him no relief:

I can explain the whistling only in this way: that the beast’s chief means of burrowing is not its claws, which it probably employs merely as a secondary resource, but its snout or its muzzle, which, of course, apart from its enormous strength, must also be fairly sharp at the point. It probably bores its snout into the earth with one mighty push and tears out a great lump; while it is doing that I hear nothing; that is the pause; but then it draws in the air for a new push. This indrawal of its breath, which must be an earth-shaking noise, not only because of the beast’s strength, but of its haste, its furious lust for work as well: this noise I hear then as a faint whistling. 12

What makes this story particularly interesting is the way it illuminates a common feature of anxiety disorders: namely, that indulging one’s anxiety tends to make it stronger over the long run. 13 Interestingly, despite his struggles with anxiety Kafka never attempted to self-medicate using alcohol, the one sedative he certainly would have been aware of. 14

The preponderance of evidence suggests that Kafka might have had a form of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, or ADHD. This extremely common neurological condition causes problems with attention, impulsivity, emotional regulation, and often hyperactivity, which impede one’s ability to take productive action. 15 Notably, Kafka’s journal entries surrounding the writing of The Trial refer to periods of writing uninterrupted late into the night, followed by periods of no writing at all. This uneven attention, in which hyperfocus coexists with a lack of focus, is a hallmark of ADHD. 16 People with ADHD also interpret time in unusual ways; it’s often said that they recognize only two times: “now” and “not now.” 17 Indeed, at least two of Kafka’s stories, A Country Doctor and A Common Confusion, seem to distort the characters’ (and readers’) perception of time. In both of these stories, the protagonists go on journeys that take wildly different amounts of time, even when the distance covered remains exactly the same. ADHD also makes one more likely to suffer depression and stress-related disorders, especially obsessive compulsive disorder. 18

An Overview of Kafka’s Writing

Kafka specialized in darkly-humorous short stories and novels that explore the absurdity and alienation of modern life. His novels, in particular, make references to petty bureaucracy and how frustrating it is to deal with. Many of his short stories feature non-human animals who are endowed with a human-like intelligence. A common theme in both is how other people–who are sometimes authority figures and sometimes not–conspire to take things or people away from the protagonists, while they themselves are powerless to stop it. Many of his writings are semi-autobiographical, drawing from episodes in his own childhood, and in a few cases (most notably his novels) Kafka even seems to be writing himself into the story.

Most people assume that Kafka’s stories are very difficult to understand. Indeed, one research article coined the term “the Kafka effect” to explain how an encounter with something strange or confusing can improve people’s ability to recognize patterns in other areas. 19 The problem is that the researchers did not use any of Kafka’s original stories, but only a modified version of the story A Country Doctor which transformed the doctor into a dentist. The stories used in the study also omit the most important aspect of A Country Doctor, which is that doctors in the modern secular age occupy a loftier position than they deserve or, indeed, even want.

In any event, Kafka’s stories are nowhere near as baffling as they are often made out to be. In order to read them properly, however, one must learn to ignore their stranger and more confusing aspects or, at very least, be selective about which ones they pay attention to. Once the reader engages their willing suspension of disbelief, the stories’ overarching meanings become clear almost immediately, and most of them aren’t that subtle, either.

Jewish Themes in Kafka’s Writing

Although Kafka was never conventionally religious, his Jewish heritage played a major role in his writing. Probably the only twentieth-century Jewish writer to leave a greater impression on the non-Jewish world is Anne Frank. References to Jewish culture and practice abound in Kafka’s stories, with varying degrees of subtlety. Indeed, one of the pleasures of reading his stories, from a Jewish perspective, is to enter a world in which Jewish ways of thinking are simply accepted as normal.

One way in which Kafka talks about Jewish life is to compare Jews to non-human animals, such as apes (A Report to an Academy), dogs (Investigations of a Dog), or mice (Josephine the Singer). A Report to an Academy is particularly interesting because it could be interpreted as a jab at Kafka’s own father. This story depicts an ape who has learned to speak and dress as a human, and thus declares that he is now a man and no longer an ape. Kafka’s father, similarly, lived a life indistinguishable from that of the wider non-Jewish culture and was openly contemptuous of religious Jews–including many of Kafka’s own friends. Kafka takes his father to task for this in Letter to His Father:

Through my intervention Judaism became abhorrent to you, Jewish writings unreadable; they “nauseated” you.–This may have meant you insisted that only that Judaism which you had shown me in my childhood was the right one, and beyond it there was nothing. Yet that you should insist on it was really hardly thinkable. But then the “nausea” […] could only mean that unconsciously you did acknowledge the weakness of your Judaism and of my Jewish upbringing, did not wish to be reminded of it in any way, and reacted to any reminder with frank hatred. 20

This type of attitude, which has its roots in millennia of expulsions, persecutions, and murder, is still prevalent among a certain class of Jews today, and one blogger known by the handle Elder of Ziyon labels it “galut (diaspora) mentality.” He explains it thusly:

This mentality is one where the Jews know that they not [sic] truly a full member of society. They are like guests in someone else’s house, and the host can choose to kick them out if they become too demanding.

[…]

[For such people] the Jews, and seemingly only the Jews, must always be subservient, undemanding of their own rights. Other peoples – devout Muslims, First Peoples, Chinese – can proudly celebrate their own culture and beliefs in front of the world, but the Jew must be quiet and deferential.

[…]

The twin rules of the assimiliated[…] Jew is [sic] to dilute Judaism to the minimum possible and to not tolerate any Jew who actually stands up for specifically Jewish rights. 21

The central irony of A Report to An Academy is that however much the protagonist may deny it, he is still an ape after all. He can never truly become a man, no matter how hard he tries to act like one. This, too, echoes the belief of both Jews and many anti-Semites that it is impossible for a Jew to ever be anything else, no matter what kind of life they live.

The Metamorphosis: Kafka’s Most Famous Story

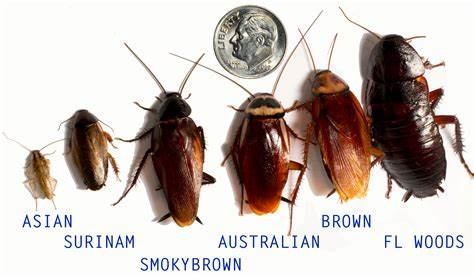

Of all of Kafka’s writings, The Metamorphosis is the one people are most familiar with. This novella-length work describes the transformation of a traveling salesman named Gregor Samsa into a giant insect. His family is horrified, not least because he can no longer provide for them, which means that they have to find work themselves. Gregor’s sister and mother attempt to care for him at first, by providing him with food and cleaning up after him, but eventually everyone in the family grows to despise him and see him as a tremendous burden. Once, when he emerges from his room, his father throws apples at his head, one of which ends up seriously injuring him. Gregor tries to remain hidden away as much as possible, but when the family takes in some boarders, he can’t resist sneaking out of his room to hear his sister play them a song on her violin. Gregor’s family is furious that he spoiled their evening, and in the aftermath, Gregor retreats to his room, from which he never again emerges. Meanwhile, his family members go about their daily lives and don’t miss him in the slightest bit.

As is the case with most of Kafka’s stories, people assume that The Metamorphosis is more esoteric than it actually is. The metaphor at the heart of the story becomes perfectly straightforward, however, when one considers what an insect is. Insects, after all, are invertebrates, a type of creature defined by its lack of a backbone.

In other words, the real point of The Metamorphosis is that Gregor is, figuratively, spineless. Despite his family’s cruel and dismissive treatment of him, Gregor never bothers to stand up for himself and almost never takes any action to improve his position. The text points out that he never asks for food, no matter how hungry he is, and that he preemptively hides away when his sister comes to clean his room, even after she has had months to get used to his new appearance. Moreover, it’s implied that his family cared little for him even when he was working and essentially relegated him to the role of a money machine. As long as he brought home money, they stayed at home and refused to go to work, even though Gregor only took the job as a salesman to pay off his father’s debts. Yet, Gregor went along with this arrangement until he simply could not work anymore. Over the course of the story Gregor allows his family to walk all over him until he becomes a literal invertebrate, and subsequently loses control even over his own body.

There is one occasion in which Gregor does contemplate taking action. As his sister plays her violin for the family’s boarders, Gregor becomes spellbound and revisits his plan of sending her to a conservatory to study music.

He was determined to push forward till he reached his sister, to pull at her skirt and so let her know that she was to come into his room with her violin, for no one here appreciated her playing as he would appreciate it. He would never let her out of his room, at least, not so long as he lived; his frightful appearance would become, for the first time, useful to him; he would watch all the doors of his room at once and spit at intruders; but his sister should need no constraint, she should stay with him of her own free will; she should sit beside him on the sofa, bend down her ear to him and hear him confide that he had had the firm intention of sending her to the Conservatorium, and that, but for his mishap, last Christmas–surely Christmas was long past?–he would have announced it to everybody without a single objection. After this confession his sister would be so touched that she would burst into tears, and Gregor would then raise himself to her shoulder and kiss her on the neck, which, now that she went to business, she kept free of any ribbon or collar. 22

However, he doesn’t have the strength to follow up on this plan. Instead, when his family rejects him yet again, he goes back to his bedroom and gives up on life completely. He accepts that his family would be better off if he disappeared, and–supposedly–bears them no ill will for it. The implication is that if he can’t take action, or get back at his family for their mistreatment of him, then he will resign himself to being a martyr so that he can be above reproach.

The Metamorphosis also speaks to a problem that has often confronted Jewish communities. Many times throughout the centuries, Jews who had been valued by their local communities for bringing in money found themselves treated like vermin with almost no warning. The Nazis, in particular, were noted for their writings and pictures describing the Jews as vermin or diseases. 23

The Trial and the Kafkatrap

The Trial is Kafka’s most famous and widely-read novel, and is also well-respected in the genre of dystopian fiction. In this story, a man named Joseph K. is arrested one day for no apparent reason, and ordered to report to a mysterious Law Court, completely removed from the official law court in his country, for trial. Along the way, K. interacts with many characters involved in the Law, among them a sociopathic lawyer named Dr. Huld, a servant-girl named Leni, and a painter named Titorelli. These individuals give K. information and advice, but do little to affect the course or outcome of the trial, which eventually takes over K.’s entire life. Ultimately, two men show up at K.’s home and execute him by stabbing him through the heart with a knife. K.’s last words are “Like a dog.” The exact sequence of events in the novel is unclear, since it was published posthumously and Kafka never bothered to arrange the chapters in order.

The Trial also gave rise to the term “kafkatrap” which was coined in 2010 by a blogger named Eric Raymond. The basic formulation of a kafkatrap is that any refusal to admit that one is guilty of heresy or thoughtcrime is itself proof that one is guilty of heresy and/or thoughtcrime. The standard kafkatrap also has a number of corollaries and addenda, some of which include the following:

Even if you do not feel yourself to be guilty of [heresy], you are guilty because you have benefited from the [heretical] behavior of others in the system.

Even if you do not feel yourself to be guilty of [heresy], you are guilty because you have a privileged position in the [heretical] system.

The act of demanding a definition of [heresy] that can be consequentially checked and falsified proves you are [a heretic].

Even if your innocence is proven in a court of law, this not only confirms your guilt; it also confirms the guilt of the legal system that found you innocent. 24

The irony is, although all these ideas may be worthy of consideration in their own right, they have virtually nothing to do with The Trial. It is true that K. is unjustly accused of a nebulous crime, but that is the only similarity between these situations. Nobody ever accuses K. of being a heretic, not even on the sort of trumped-up charges that would-be inquisitors use to ensnare alleged heretics in real life. The entire point of The Trial is that there is no reason for K.’s arrest, and no particular reason for his trial other than, apparently, to make him grovel and suffer. Indeed, the novel itself opens by saying “Someone must have been telling lies about Joseph K., for without having done anything wrong he was arrested one fine morning [emphasis added].” The most obvious real-world analogues to The Trial are the situations faced by abuse victims and oppressed minorities, both of which Kafka was.

Kafka’s Continued Relevance

The most striking thing about Kafka, however, may be the way in which his life and writings remain relevant even to this day. In fact, if anything, there are probably a lot more Kafkaesque individuals and situations now than there were during his actual lifetime.

As many people have observed, several of Kafka’s stories seem unusually prescient. The Metamorphosis, as previously noted, provides a fairly accurate description of the attitudes in Nazi Germany, where the Jews were seen by the authorities as vermin to be eradicated. A Country Doctor also contains this fascinating thought:

That is what people are like in my district. Always expecting the impossible from the doctor. They have lost their ancient beliefs; the parson sits at home and unravels his vestments, one after another; but the doctor is supposed to be omnipotent with his merciful surgeon’s hand. 25

This quote holds particular resonance in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic, in which many medical professionals and organizations really were elevated to an almost holy status. The confused spiritual quest in The Castle, meanwhile, will seem eminently relatable to many moderns who are searching for God in a world where he seems more remote than ever before.

Still, Kafka’s relevance goes even deeper than this. As previously mentioned, Kafka rarely saw either of his parents because both worked long hours in the family business. At the time this may have been unusual, but nowadays, many more people have parents whose jobs force them to be absent for long periods of time. Moreover, unlike the Kafkas, many of these families can’t afford nannies, and so they send their children to communal day care centers instead. The famous philosopher Ayn Rand describes a child’s experience in a day care center (which she calls a “Progressive nursery school”) in a distinctly Kafkaesque fashion:

He does not know what to do; he is told to do anything he feels like. He picks up a toy; it is snatched away from him by another child; he is told that he must learn to share. Why? No answer is given. He sits alone in a corner; he is told that he must join the others. Why? No answer is given. He approaches a group, reaches for their toys and is punched in the nose. He cries, in angry bewilderment; the teacher throws her arms around him and gushes that she loves him.

[…]

A child needs to reach a certain development, a sense of his own identity, before he can enjoy the company of his “peers.” But he is thrown into their midst and told to adjust.

Adjust to what? To anything. To cruelty, to injustice, to blindness, to silliness, to pretentiousness, to snubs, to mockery, to treachery, to lies, to incomprehensible demands, to unwanted favors, to nagging affections, to unprovoked hostilities–and to the overwhelming, overpowering presence of Whim as the ruler of everything. 26

Of course, Rand wrote this essay in the early 1970’s, and may have been exaggerating a little bit. However, in the early 2000’s, the sociologist Brian C. Roberston pointed to evidence suggesting that “the correlation found between behavior problems and the amount of time spent in nonmaternal care […] was just as statistically significant as the correlation between behavior problems and two other risk factors already widely acknowledged: poverty and abusive or uncaring parents [emphasis added].” 27 What all this suggests is that if more modern people took the time to read Kafka, they would actually be able to relate to many of his stories surprisingly well.

Franz Kafka has a reputation for being a crazy or incomprehensible writer, but this is not altogether fair to him. His writings have much to teach a confused modern reader about the workings of the world, particularly if that reader is Jewish. Through reading Kafka’s stories, or studying his deeply tragic life, the audience gains a first-hand look at the perspective of someone who feels powerless.

Works Cited

- Michaelson, Jay. “Golem.” My Jewish Learning, 2021. www.myjewishlearning.com/article/golem/ ↩

- “Parents.” Franz Kafka Museum, 2020. kafkamuseum.cz/en/franz-kafka/family/parents/ ↩

- Popova, Maria. “Kafka’s Remarkable Letter to His Abusive and Narcissistic Father.” Brain Pickings, 2015. www.brainpickings.org/03/05/franz-kafka-letter-father ↩

- “Early childhood.” Franz Kafka Museum, 2020. kafkamuseum.cz/en/franz-kafka/educational-career/early-childhood ↩

- “University.” Franz Kafka Museum, 2020. kafkamuseum.cz/en/franz-kafka/educational-career/university ↩

- “Employment.” Franz Kafka Museum, 2020. kafkamuseum.cz/en/franz-kafka/employment/ ↩

- “Sisters.” Franz Kafka Museum, 2020. kafkamuseum.cz/en/franz-kafka/family/sisters/ ↩

- “Max Brod.” Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia. Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia, 21 May 2021. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Max_Brod ↩

- “Dora Diamant.” Franz Kafka Museum, 2020. kafkamuseum.cz/en/franz/kafka/women/dora-diamant/ ↩

- Ellis, Bruce J. and W. Thomas Boyce. “Biological Sensitivity to Context.” Current Directions in Psychological Science. vol. 17 (2008): 183-187 ↩

- Crumb, Robert & David Zane Mairowitz. Kafka. Seattle, WA: Fantagraphic Books, 2007 ↩

- Kafka, Franz. The Burrow. Selected Stories of Franz Kafka. Trans: Muir, Willa & Edwin Muir. New York: Random House 1952 ↩

- Schwartz, Jeffrey M. & Beverly Beyette. Brain Lock: Free Yourself from Obsessive-Compulsive Behavior. New York: Harper Perennial ↩

- Martyris, Nina. “For Kafka, Even Beer Came With Baggage.” NPR, 11 April 2016. www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2016/04/11/473158881/for-kafka-even-beer-came-with-baggage ↩

- Hallowell, Edward M. & John Ratey. Delivered from Distraction. New York: Ballantine Books, 2017 ↩

- Green, Rick. “Hyperfocus and ADHD | Why Can I Focus Some times and Not Others?” Totally ADD. totallyadd.com/adhd-video/he-can-focus-when-he-wants-to/ ↩

- Hallowell & Ratey, 2017 ↩

- Olivardia, Roberto. “Anxiety? Depression? Or ADHD? It Could Be All Three.” ADDitude, 9 July, 2021. www.additudemag.com/adhd-anxiety-depression-the-diagnosis-puzzle-of-related-conditions/ ↩

- Proulx, Travis & Steven J. Heine. “Connections From Kafka: Exposure to Meaning Threats Improves Implicit Learning of an Artificial Grammar.” Psychological Science, Vol. 20 (2009): 1125-1131 ↩

- Kaiser, Ernst & Eithne Wilkins, translators. Letter To His Father. By Franz Kafka, Schocken Books, 1966 ↩

- Elder of Ziyon. “Leftist Jews fetishizing the Diaspora to justify their hate for Israel.” Elder of Ziyon, 26 September 2019. https://elderofziyon.blogspot.com/2019/09/leftist-jews-fetishizing-diaspora-to.html ↩

- Kafka, Franz. The Metamorphosis. Selected Stories of Franz Kafka. Trans: Muir, Willa & Edwin Muir. New York: Random House 1952 ↩

- United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. “Jews Are Lice: They Cause Typhus.” Courtesy of Archium Panstwowe w Lubline. Copyright of United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. perspectives.ushmm.org/item/jews-are-lice-they-cause-typhus ↩

- Frank, Michael. “7 linguistic tricks people use to deceive and manipulate you.” Life Lessons, 2019. lifelessons.co/critical-thinking/kafkatrapping ↩

- Kafka, Franz. A Country Doctor. Selected Stories of Franz Kafka. Trans: Muir, Willa & Edwin Muir. New York: Random House 1952 ↩

- Rand, Ayn. “The Comprachicos.” The New Left: The Anti-Industrial Revolution. 1970 ↩

- Robertson, Brian C. Day Care Deception: What The Child Care Establishment Isn’t Telling Us. San Francisco, CA: Encounter Books, 2003 ↩

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Great article.

I’ve always thought they should teach Kafka and Camus in schools instead of religious education, or at least as a contrast to Religious teachings.

No two writers better captured the pointless nature and meaningless struggle of human existence, and in such wonderfully captivating prose.

It would certainly give teenagers something to be miserable about.

Thing is, I don’t think Kafka was anti-religious as such. He may not have lived a religious life, but he did have many religious friends, and he got very interested in the mystical aspects of Judaism in his later years. Indeed, one of the conflicts he singles out between himself and his father is that he (the son) was too absorbed in his religious and cultural heritage, and his father resented him for it.

Some reasonable things, here. Thank you fore reminding us of the short-changed genius.

The term Kafka and Kafkaesque is so overused it’s lost it’s meaning.

Kafka clearly isn’t overused as my predictive text tries to turn it into Kaka.

Absolutely true.

After a day dealing with German bureaucracy in Berlin I saw a poster advertising the no alcohol for children program, on the door of a hotel. In German:

Kein Alkohol Für Kinder Aktion. They printed the acronym underneath:

K.A.F.K.A

I was, I must admit, a little frightened!

“Nothing.” — Kafka, Diaries, 22 September 1917

All words eventually become useless with misuse and overuse. The effective usefulness range ranges between 1 and 43. An overused misused word is finally ground to dust and designated by the lessness of its use. Best words are those that are used once and then disused.

How kafkaesque.

It would be more so if his information came from The Department of Effective Linguistic Usage which sent very official looking letters, but the address was one room, staffed by a midget in a wheelchair, who kept insisting there was a queue to see him when there wasn’t and, after five hours, informed you that you must return home and join the back of the queue tomorrow.

If Kafka had been Franz Higgins, his name would not have been over-used. Kafka is a brilliant word and super-villain name. Even if he’d only written recipe books, we would now refer to their style as ‘Kafkaesque’.

In fact, most people would not have read the Trial at all if it had been written by Franz Higgins.

True, the word Kafka sounds good in its own right but Kafkaesque is just delightful, any excuse and I use it, abuse it, misuse it, over-use it and thereby render it meaningless, unfathomable, abysmally opaque, mind-numbingly obtuse and, yes, frightfully Kafkaesque.

Surely in Prague where he lived, “Higgins” would have been a far more exotic sounding name than “Kafka”.

Funnily enough it’s not one of the words that first springs to mind when you wake up and find you have been transformed into a giant insect.

The loss of meaning of Kafkaesque is Kafkaesque.

Kafkaesque is probably not as overused as “surreal”, which gets pressed into describe almost anything a bit odd, eccentric, or unusual. If only some vast unseen bureaucracy, some organ of state, could patrol our use of language and subject those devaluing it to an opaque and terrifying process of judgement and retribution…

If you drop “Kafkaesque” in a conversation 90% people won’t know what you’re talking about. It also won’t make you look smart as someone intelligent gets their point across succinctly without being inscrutable or verbose.

Anyone who feels intellectually inferior to you will be impressed by any highfalutin term you use, and if you replaced “Kafkaesque” with any gobydigook like “mufillicle” they’d be none the wiser.

The 10% people au fait with the term’ll think you’re pretentious for using it and you’ll only come across as a pseudo intellectual trying too hard to impress your cerebral peers.

Unfounded claim.

I remember when I read Metamorphosis thirty years ago. I was feeling down a lot of days.

Revisiting The Metamorphosis recently during my online book club, and reading it in German, I was struck by the obsession on “naming the creature” which seems to plague most English translations.

A similar- for my tastes, futile- obsession with a never achievable “verisimilitude” inhabits much of the previous discussion. I think German, surprising though this might seem to English speakers, is a language in which abstract discourse is made easier; it is possible to discuss things without “naming names”. (Perhaps that is also one small part of the flaw which destroyed German culture in the mid 20th century- an ability to “avoid” actually thinking about uncomfortable specifics.)

In German no-one wonders about what sort of creature Gregor has become. He is simply, instantly transformed into something so objectionable that even his own family doesn’t want it in the house any more, regardless of whether they are related to it. There is also, for me, the question about whether his dreams were about how thin the carapace of “civilisation” is; perhaps this realisation catapulted him, Matrix-like, into a mode of being which rendered him unpalatable to his “believing” contemporaries.

On that basis, I read the story more as a riff on the theme of “undesirables”, and social outcasts- Gregor is implanted into his family as the embodiment of whatever it is that society at that moment most abhors. And not even familial bonds are sufficient to preserve their relationship with him, under those circumstances.

Translations which dwell more on the ideas, rather than the specifics, of the story are therefore, for me, the more successful ones.

Gregor Samsa had to be a beetle. Why? Simply because many years ago as astudent of German my room was next door to another, older student of German who ahd been celebrating finishing his finals. The middle of the night he awoke to find that a large may bug or similar had landed inside a glass on his desk. The screams were indescribable. I haven’t read Die Verwandlung for ages. In fact I haven’t read it since about 1971.

How prescient that Kafka, as a Jew, wrote about being transformed into vermin, given how Jewish people were portrayed by Nazi propagandists ten years after his death. The racism would have been in it’s nascent form while he was alive though. The best writers are always sensitive to nuances and undercurrents around them, transforming them into powerful metaphors so that they can be understood on the same visceral level by others.

To me Metamorphosis portrays the contempt for disabled people that was also part of the rising fascist ideology: the resentment against ‘useless eaters’. His role as a workplace accident insurance investigator (in which he seems to have encountered many people disabled by their work), seems to have informed the work, as well as his own ill-health (for which he was harshly judged as being hypochondriac, and even harshly judged himself as such, another interesting aspect of how disabled people are treated, especially with, for example, present day ‘scrounger’ rhetoric in the UK). Metamorphosis to me really hits the nail on the head in presenting some of the more pernicious attitudes to disabled people, including the ‘better off dead’ hypocrisy which is endemic in how disabled people are viewed even now. I believe this is a plausible reading, in addition to his insight from being a Jew during this period. It is dismaying that so few people, especially among the ‘literati’ even consider this aspect of the story.

How is giving a plausible reading of Kafka’s own life and concerns and how it may have predicted – or even just represented for him then present – ideologies at both macro and micro levels of his and others’ lives turning him into a saint? Also – people do have a habit sometimes, especially writers, of predicting future turns of public ideology. History is not often separate from literature in terms of the circumstances in which it is produced. To believe that it is becomes a little too ‘neatening’ in itself, or leads to a belief that language and narrative is produced context free, which is implausible.

I have always read Gregor’s tranformation into an Ungeziefer as representing (and transparently so) Kafka’s neurotic-political fear of the anti-semitic fervour.

It’s one possibility, certainly. But there’s not much direct evidence in the text, and Kafka doesn’t otherwise have too much to say about anti-Semitism.

Excellent piece.

I find there is very little good writing on Kafka: there is surely no other author whose work is more resistant to explication. It’s also impossible to teach: what does it mean? The best thing is simply to highlight an individual episode and let it resonate.

Once again, lovely article! Before this, I only knew Kafka in connection with The Metamorphosis, and while that’s a great story, he’s clearly so much more.

When I think of Kafka, I think of how he reminds me of the absurdity of life. Disaffection and isolation as well, especially in regards to the time and place in which Kafka lived, and how he lived. Much like Heller’s Catch 22, although different in style, they both point to the arbitrary nature of misuse of power.

If you feel lost in a blind system, or obscurely persecuted by an authority that doesn’t even care enough to be evil, or hate you, then you are Franz territory.

With The Metamorphosis, I don’t remember which creature was mentioned in the first version I read, but I have always ‘seen’ it as some kind of beetle.

I totally agree. I have always imagined Gregor to be some enormous beetle. Again, I really don’t know why.

Well, the description is of a beetle and when he dies the cleaner who throws his body into the bin describes him/it as a “dung beetle”.

I always think of Metamorphosis as a novella. For me the greatest short story ever is Poe’s Fall of the House of Usher. Which is when the human mind itself became the most important topic in Literature.

I was once in Prague and was looking forward to seeing the house where he was born….only to discover it had been demolished some time ago…I did sample his favourite sausage in his favourite cafe and watched the rather dour looking locals go about their business…I remember it was so cold my trainers fell apart and I remember the ubiquitous cash converter kiosks…and the millions of pencils and pens with Kafka’s name emblazoned on the side…

It wasn’t what I expected.

I return often to Kafka’s writing, and enjoy these types of articles.

I would like to add that Kafka is one of those writer where you really benefit by reading a large body of his work and not a few short-stories. I think the stage productions and movie adaptations and pop culture references really do harm than good.

Kafka wrote parables with almost archetypes (perhaps I have difficulty here in expressing exactly what I mean. that is why I suggest reading Benjamin) and you only glean through the deliberate mist once you have read enough Kafka. For example the true nature of the protagonist K can only be gleaned (I say gleaned and not understood as I think, to try and understand Kafka the way we understand the our world post enlightenment is a fruitless exercise) if one reads Castle, Trial and Amerika.

I also think that all this interpretation in terms of loneliness and lost in a bureaucratic maze and other such things are merely projections on Kafka’s works and perhaps have little to do with the actual text.

I feel to better engage with Kafka, one has to go closer to the actual text and not try to interpret it through mundane themes.

I read Kafka in my late teens, and early twenties but not since (I’m in my fifties now) and I think its time for a reread. He made a huge impact on me at the time – I was an angstful young man, I’ve no doubt there were some oh woe is me romantic attraction/identification with his work at the time. But I was terrified by some of his work. And also at the time I was stuck in the height of apartheid South Africa in the late seventies/early eighties, so I couldn’t but help relate it to, and see the reflections of the madness of that society in work like the Trial, and the Castle, and the Penal Colony.

So I am intrigued by what you say, and I will reread some of his stuff – funny, I just recently picked up a ridiculously cheap first edition of volumes of his letters to Milena and his diaries, so it has been in my mind to read him. And Walter Benjamen is someone who I should read more of.

Yeah, I think when you are young and read Kafka, it is actually so inaccessible that you end up rationalizing it by relating it to something that is more accessible. I think the more important point is that even as a young person you are impacted by it and find a need to somehow make it a part of your life.

However, I think after reading a lot of his work and after doing it when you are a little older, you begin to see some patterns. And I always thought these patterns are very close to the actual text itself and little to do with somehow trying to interpret it. Some of Kafka’s work, especially Penal Colony, I felt almost had the gravity of religious doctrines. The problem with me is that the moment I try and start putting into words my understanding of Kafka, I feel, I stumble and I can’t find the right words. But as I was saying, Benjamin finds the right words. And that is not really surprising, Benjamin was special.

“Kafkaesque” seems quite appropriate to me when describing Han’s novel, at least when trying to give someone an idea about what it is like to read it. The power of the male gaze, for instance, functions very much like the judgmental fathers of Kafka’s fiction (most famously in “The Judgment”). There is also the alienation of sensitive characters who are made to doubt their worth, retreating almost willingly into an alienated withdrawal from society (as in The Metamorphosis). What The Vegetarian most reminded me of, though, was Kafka’s “The Hunger Artist,” both in the disquieting way that both Han and Kafka describe a willed subversion of human biology and in the utter incomprehension that such efforts engender in others.

Excellent, brilliant, knowledgeable! More like this please.

If you want a solution to Kafka’s The Trial, try reading Orlando Pearson’s The Trial of Joseph Carr. Convincing and amusing.

We saw The Metamorphosis as a play in Oslo (with English subtitles on screens to the side), bought tickets on a whim as it was such an interesting thing to do.

We had one of the most enjoyable evenings ever and the play is still running through my mind. It was amazing bewildering, funny and most certainly thought provoking.

A very informative and comprehensive post!

The biggest merit of “Metamorphosis,” in my opinion, is its realism. The story would be worth a lot less if it wasn’t believable to the reader. So it presents a great opportunity for any writer to study realism in fiction.

After all, what would be harder to sell to your reader than a man turning into a bug…?

I agree and I think a lot of it comes back to willing suspension of disbelief. It’s something people understand intuitively about other writers. The audience can overlook a lot of strange or “unrealistic” details about a story’s world as long as the characters behave in the way that they would expect real people to behave in those situations. If you think about it, the Lord of the Rings series (for instance) isn’t “realistic” either insofar as it takes place in a fantasy world, but the characters still behave in ways that are plausible and so they resonate with the audience. It’s the same thing with Kafka.

I read Kafka 40 years ago as a 12 year old, and I’ve never forgotten.

This does illustrate well the writings of a troubled, brooding author, often misunderstood. Good job on this!

I’ve just realised that I’ve fused Kafkaesque with just about everything I don’t like (most things).

Very well written.

Lots of articles on Kafka are disappointing, this isn’t. It’s very rare that I find one worth reading. Indeed, I often wonder if Kafka has been read at all by any of his commentators or critics.

Kafkaesque derives far more from The Trial. I think that Trial gives more of an insight into Kafka the man than Metamorphosis containing voyeurism, frustrated love affairs, powerlessness, the banality and overpowering soul sickness of the then modern office life (a la Brazil) and the ultimate self-sacrifice before unknown, faceless, nameless powers that operate in our name totally counter to our wishes.

Maetamorphosis is certainly open to a wide range of interpretations – I suppose that is one reason why it is so fascinating!

As far as Kafka industry churn-out goes, this article is really good.

The license of this writer was astonishing for me when I read his work back then, completely absurd yet easy to understand.

Edward Watson’s portrayal of Gregor at the Linbury theatre in 2011 was one of the most powerful, moving and disturbing pieces of dance theatre that I have ever seen. Arthur Pita’s choreography is a work of genius and truly conveys the essence of this Kafka work.

Wish I’d seen that.

Must read Kafka again, especially Metamorphosis!

Kafka’s stories showed me that our actions, thoughts and decisions can never be completely sourced, explained or validated, so they are expressions of faith. In ‘the trial’, the helplessness of this state is laid bare by an inexplicable accusation. The hero is not religious and does not create a mental construct of his faith, leaving him all the more at mercy and without solace. In ‘the castle’, the apparently reasonable assumption that if you approach a place you will get there, is flawed. In that book the absurdity of some of the situations reminded me of Monty Python.

I am a godless man and proud of it, but I acknowledge that my life is an expression of faith too. We’re all guilty.

Thank you to Kafka for his great work.

This is the first article I read on this site and the fact that I just signed up should speak volumes.

Can very much relate to the ADHD aspect of Kafkas life but also inspired me to get my ass going and get my own writing in.

Great read.

A random Kafka story. Whilst getting ready to stay in a very remote part of Cambodia. I really wanted to read The Metamorphosis having not done so for over 20 years. However trying to find it proved very difficult and not having access to technology I gave up on trying to get it.

Get to the cabin where I’m staying. Whilst picking up something on the floor. I see a book underneath the bed.

Lo hold and behold. The Metamorphosis.

The opening page was signed with ENJOY.

I really did. What a strange ass world

I loved your synchronicity-styled discovery of the Kafka book under the bed! Super cool. Thanks so much for sharing. Reminded me of a book by Phil Cousineau titled Soul Moments, which is a collection of those kinds of synchronicities. Two other excellent books on the subject of synchronicity are C. G. Jung’s Psychology of Religion and Synchronicity (by Aziz) and Synchronicity: Nature & Psyche in an Interconnected Universe (by Joeseph Cambray).

Glad you mention humor in the article. Since I do believe that Kafka was a funny man.

He absolutely was a funny man. It’s my understanding, at least according to the testimony of Kafka’s friends, that all he really wanted was to write funny stories.

Ive heard Tolkinesque. Murakamiesque and Rowlingesque have yet to make an appearance as far as Im aware.

I’ve definitely come across ‘Tolkeinesque’…

As I approach my senior years I offer up my response to Metamorphosis. Perhaps too simple. I did not see the insect as an analogy for a lack of backbone exactly. I see it as an illustration of how humans can experience a transformation overnight through a sudden illness, change in income level, or indeed any change in life circumstances that will make others see them differently, behave differently around them, and even shun them. Consider the indignity/isolation of old age as one example which many of us will experience where family and friends no longer seek out our company and conversation. I have just read that in the wake of the current conflict in the Ukraine, the Russian Bolshoi Ballet summer season at The Royal Opera House in London cannot go ahead. Overnight, their status has been transformed. As McCartney wrote. ‘How I long for yesterday’. For me Kafka helps us to understand the personal impact on others of our response to changes beyond their control.

Great article!

Great article – a thorough and well presented insight on a man whose work I’m now motivated to become far more familiar with!

I can see absolute merit in your claim that Kafka is misunderstood. My attempts to read and understand his writing have always been unsuccessful. Though I am unable to see myself becoming a frequent reader of his work, your article will prove a valuable resource next time I do attempt to delve into his writing.

For me the key to understanding Kafka is really just the simple recognition that life can be just like the worlds he creates through his art. You go here to turn in this form and are told you have to first go to this other office–like when you’re trying to get a passport or do anything official, really. It can be so, well, kafkaesque! He portrays that with such force and leaves you wondering what’s behind it all, hidden beyond the reach of the bureaucrats. I don’t know that he really answers the question or ever really intended to. Sometimes it’s enough to just ask the question….

Love this!

Kafka’s thinking that we are only degrees away from being a part of the wild always sticks out to me.

Wait, you guys don’t understand Kafka’s meaning after one read?

This article draws on a wide variety of sources, Kafka’s writings, facts of his life, and psychological literature, to understand Kafka’s mind and how this influenced his writing.

What a fine and inviting introduction and summary overview of Kafka’s life and work. For anyone with an interest in a psychoanalytic take on Kafka there’s a fine essay by the cultural anthropologist Ernest Becker in his book, Angel in Armor. But I totally agree with this author of this piece that Kafka need not be intimidating. Seems to me he can be read much like William Hurt watching a movie in the movie, The Big Chill (just let the art flow over you).

The Metamorphosis was the most uncomfortable thing I’ve ever read

A good essay. Well done, thoughtful and I enjoyed your views on his writings.

A great piece!

Excellent article. Kafka was a truly singular writer, few authors can claim to have coined a whole new term.

The notes on Kafka’s biography are interesting, though I had come across bits and pieces of some incidents in his life mentioned here. Kafka’s life and works reminds me of the uniqueness of each individual human being. Probably, there is a deliberate attempt to reiterate the strange reality of everyone’s difference from the others, displayed by each of Kafka’s characters. Interestingly, the life of Kafka was not different either, in this sense.

Great article! Thank you Deb!

For anyone interested in Kafka, Don Marquis had an interesting and forgotten newspaper column called “archy and mehitabel” that follows archy: a poet who has been reincarnated as a cockroach in NYC. Since Don Marquis made the character in 1916, and Kafka wrote The Metamorphosis in 1915, they might be connected, especially if you note the theme of pieces like “Why Not Commit Suicide”

“well boss from time

to time I just simply

get bored with having

to be a cockroach

my soul my real ego if

you get what i mean is

tired of being shut

up in an insects body the

best you can say for it is that it

is unusual and you could

say as much for mumps so

while feeling gloomy the

other night the thought came

to me why not

go on to the next stage as

soon as possible why not…”