Gone Home Review: Exploration and Introspection

The short-form video game has seen a bit of a proliferation over the last 18 months. What fringe developers like Tale of Tales and Anna Anthropy once practiced has broken into the mainstream gaming consciousness. These commercial projects owe their existence to the rise of downloadable games and the explosion of independent development. Thatgamecompany’s Journey used evocative visuals and procedural characterization to weave a powerful metaphor for life and the Campbellian Monomyth, Dear Esther used environmental storytelling to tell a story about a man’s guilt over hurting his wife, and Thomas Was Alone varied the feel of each of its character’s jumps to let players tell an irresistibly cute story about friendship, love, and interdependence. This approach to game design has been remarkably successful, and last year’s Journey defied every expectation be built up over the last decade to win myriad game of the year awards.

The latest entry to the short-form canon is indie Steam game Gone Home, a first-person exploratory adventure game developed by The Fulbright Company, best known for their work on the Minerva’s Den DLC for Bioshock 2. Their authorial touch and attention to detail can be seen throughout the entire game, like in Bioshock, investigating objects and character artifacts scattered throughout the environment passively conveys the narrative to the player. Players act as archaeologists piecing together the mysteries of the gameworld to find out what happened to it and its inhabitants, a shot glass in an office, a crumpled-up piece of paper, and a self-effacing stickynote can all be imbued with narrative meaning and serve to define a character who the player never meets.

There’s no combat in Gone Home, and the few puzzles there are are rudimentary and simple, overall, the entire game can be completed in two to three hours. At $19.99, the game’s short length and high price could legitimately dissuade some players from the game, but for those willing to pay the substantial price, Gone Home is one of the year’s most poignant and engaging story-driven games.

First-Person Snooper

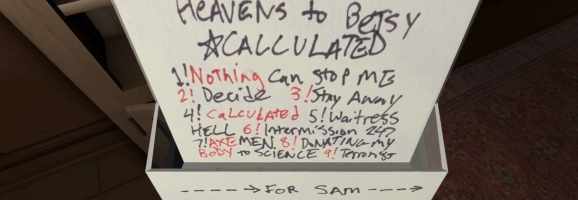

The player takes the role of Katie Greenbriar, a 20-year old college girl returning from a year abroad in Europe to her family’s new home at 1 Arbor Hill, Boon County. She arrives at at the vast mansion under the darkness of a rainy summer night to find it mysteriously deserted, with only a note from her sister Sam hastily taped to the front door asking her not to go searching for her. Katie enters the house, searching for clues that might tell her what happened to her family in the nine months she was away for college. Gone Home is at its heart a story about family drama and life as a misfit teenager, epistolarily told though mixtapes, faxes, and boxes of personal belongings taped-up and hidden away deep in closets.

Gone Home‘s progression is mostly linear, each member of the Greenbriar family has colonized a part of 1 Arbor Hill as their own. Katie explores each member’s quarters, and by picking up and examining their belongings as she goes from room to room, learns about the demons they faced during her absence. As she snoops deeper into her family’s possessions, we see the Greenbriars go through entire arcs imbued with internal conflict. Despite never appearing on screen, the spaces that these characters create and inhabit conveys a wealth of narrative information nary a line of dialogue. Despite being systemically and artistically simplistic, there’s an exciting sense of discovery to be felt when uncovering an object and discerning what it says about its owner comparable to discovering a new city in Skyrim. Elegant signposting and level design make traversal feel natural, flowing, and intuitive in a way reminiscent of Half-Life 2, even in spite of the nonlinear path that players can potentially take.

While the core story of Gone Home could have been theoretically told in another medium, the formal traits of video games are completely suitable for a story about arriving home from college to find one’s family changed. Aside from perhaps Disneyland attractions, video games are the only medium that permit the traversal of a 3D space and the examination of 3D objects (done here by rotating the mouse). Gone Home‘s choice to convey its narrative about family drama passively through created spaces and character artifacts creates a form of storytelling unique to video games. While many contemporary games make the unfortunate choice to emulate film or literature, Gone Home explores uncharted formal territory that last year’s kinetic espionage romp Thirty Flights of Loving dug open.

Mundanity is Thrilling

What is perhaps most remarkable about Gone Home‘s approach to its themes is the lens through which is contextualized. Gone Home deals with themes are unheard of in video games, in fact, a number of missions in Mass Effect 2 have dealt with very similar relationships and conflicts. But Mass Effect 2‘s epic sci-fi setting and greater emphasis on its heroic fantasy layered its more personal and relatable themes under layers of metaphor and sometimes contrived combat sequences. While fantastic metaphor has communicated some powerful fiction like Kafka’s The Metamorphosis, comparatively realistic and mundane fiction like A Raisin in the Sun is relatively more accessible. Gone Home‘s setting in suburban Oregon during the mid-nineties sets the stage for a conflict common to many contemporary families, and is paradoxically more fascinating than many of the incredibly imaginative locales to be crafted in recent games.

The care and attention to detail with which 1 Arbor Hill is crafted is comparable to even such games as Portal 2 and Bioshock Infinite. Except in place of a massive underground research facility or a floating city, we have a snapshot of upper-middle class American life in the mid-nineties. Allusions to the period are not given Forrest Gump-style with clips of Bill Clinton on the televisions or headlines about the Oklahoma City bombing, but rather through the subtle imagery and artifacts of the period: blank VHS tapes marked with Sharpie-labels, a satisfaction guarantee on a bag of chips with an address instead of an email, a period typeface on a home and garden magazine. Mixtapes with 90s grunge rock can be found in certain areas and played when inserted into stereos, adding a layer of authenticity to what is already intricately atmospheric, if not nostalgic, setting.

Gone Home‘s setting in the late 90s allows its narrative and play to hit closer to home, as the authentic recreation of a period’s aesthetics and lifestyles evoke memories of a time that its target audience has an emotional connection to. The Walking Dead and The Last of Us told stories about love, loss, and fatherhood through the distancing fantasy of a zombie apocalypse, while those games were effective in exploring themes about tribal relationships and survival, managing a conflicted party of survivors and sneaking one’s way through a bandit-occupied Pittsburgh is something that many of us will never do. Gone Home‘s mundane setting, contextualized through the eyes of a college kid returning home for the first time, can evoke bittersweet memories of one’s own adolescence and how one felt at the time.

Gone Home nonetheless is slightly marred by a few minor problems. There are times where it is unclear whether or not a puzzle can be solved with the tools the player currently has or must be returned to later in the game. This oversight could potentially send players on a lengthy hunt for a key or a password to open a door that they cannot open until much later. The visuals also suffer at lower settings, textures on objects fade into fuzziness on slower machines, compromising some of the world’s period believability.

In A Theory of Fun, academic Ralph Koster stated that video games could never achieve the narrative potential of novels because their systemic nature suits them for external conflicts about actions rather than thoughts or emotions. Play psychologically prioritizes objectification, classification, and quantification, whereas reading prioritizes empathy, introspection, and reflection. Gone Home challenges this academic dichotomy by telling a quiet, introspective story driven by the player’s actions in a virtual environment. Coupled with a touching and impactful narrative, this defiant design makes Gone Home one of the best games of the year.

Rating:

What do you think? Leave a comment.

While most of the world will keep hating that the $20 game is not by definition a game, I will celebrate that it was an explorable bit of art that told an excellent story. The voice acting was far above gaming norms, and the fact that I actually cared what happen to characters for once was a relief. In a day and age where most game characters are dispensable stereotypes this game made me care, and I applaud the creator for it. Hopefully the devs pay it forward and take this money to make the next game either much bigger, or cut some of the price, either way looking forward to their next release.

Gone Home is most definitely a game, at least by the academic definitions that I’ve encountered. Stuff like Proteus is a bit fuzzier, which might give us fuel for a pedantic flame war. Either way, loved what the Fullbright Company did here.

I completed this yesterday and it is such a joy to see it getting good reviews. I don’t think I have personally ever been more emotionally involved with the story of a game before, although that could be because I heavily identified with several aspects. I loved the house, the sense of exploration learning about its inhabitants, and despite the fact that I knew nothing was going to jump out (Although I did wonder . . .) the game had an incredible atmosphere. Gone Home gives me hope for the future of games, partly because of the creative experiment in storytelling, but mostly because it is not afraid to explore a mature and emotional story. We need more games like this.

Awesome review! This reminds me of the Sega Saturn great first person adventure games.

I have been watching this game for some time and this review has just reaffirmed what I thought about it. I’m obviously going to get it, but £13.99 seems like quite a lot for just three hours of gameplay. Might have to wait for a Steam Sale 😛

You vote with your money. If you want to see more indie games with great stories, you need to support them. $20 seems like a lot for a few hours, but you basically pay that at the movies. Sure, if it’s not in 3D you get popcorn with your $20 purchase; but with this game you get interactive immersion.

and its nice to be able to participate in the discussion around the game if your immediate community is also into indie games.

This game’s interesting in the fact that it’s scary when there’s nothing going on. A couple of times I was expecting something to leap out and do a jump scare on me, and there’s surprisingly nothing at all, which makes me even more anxious. ESPECIALLY when you get farther. I can’t wait to finish this game!

Looks like an amazing game that’s the thing about indie devs, their games, even if they have a low budget, can be better than triple-a games since they aren’t tied to big publishers with big expectations, they can do whatever they want as long as they have the heart and effort for it.

Spoilers. Ultimately this game left me unsatisfied. Some people are just bad for each other, and such is the case with Sam and Lonnie. Watching Sam grow up as the game progresses you see her go from a sweet child to belonging in juvenile hall. She begins lying to her parents, smoking, stealing clothing, giving up an almost free ride at a good college, and ransacking all her family’s VCRs (and Laserdisc players) before running off with her friend, all before turning 18.

Sure, you can argue that finding love is a great thing, but you can’t tell me those changes and choices are good for her. The girl is going to suffer out there, and so the ending made me sad despite the obvious happy spin The Fullbright Company tried to put on it.

I disagree, I think her tough and complicated adolescence was really well done, her character arc is a bildungsroman of a lonely and misfit teenager reminiscient of something like Holden Caulfield from Catcher in the Rye. Considering she was always in the shadow of her high-achieving sister, and had just moved to a new school not too long ago, I think her behavior is forgivable.

in retrospect, that tough phase of one’s life seems stupid and blunderous, especially as a much better-adjusted adult, but don’t forget how one saw the world and one’s place in it at that particular age.

I just heard about this game for the first time this morning through another review that praised it much as you did. While I don’t game as much as I used to, it’s refreshing to hear that such boundary pushing games are being made and that the community is continuing to thrive with so much creativity. You have a very well written review here. I’m definitely going to try to check it out in the near future.

I’ve heard about this game before, it seems deeply immersive – I reckon it will appeal to readers of detail-orientated novels as well as gamers, because in a similar way to that type of novel (I’m thinking Gatsby, realist Victorian fare) it’s about exploration instead of following plot and actions. This is a game I want to play! Thanks for such an informative review 😀

This game looks so unlike anything I’ve ever seen

I believe you’ve proven Ralph Koster wrong.

The reason for the thrill of the mundane side because one never knows when the mundane stops and when a shock will come.