Harry Potter and the Journey of Identity Formation

This article is based on the books, not the films.

It is estimated that “120 million people have read at least one Harry Potter book” (Beach 105). While it is entirely probable that J.K. Rowling never meant the series to be anything more than an engaging tale of a boy wizard’s adventures, one can find in the series a sophisticated account on the process of adolescent identity formation. It can be argued that the series offers an account of the inevitable and necessary differentiation from parents that all adolescents must undergo in order to form their own identities. One of the reasons for Harry Potter’s immense popularity, therefore, is because it models for adolescents a way of successfully completing this identity formation.

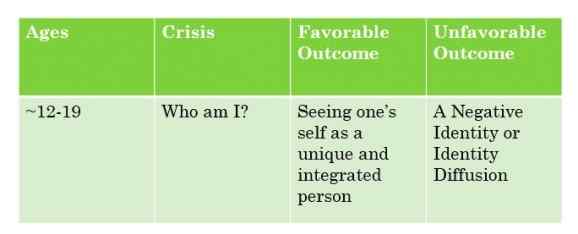

Erik Erikson’s Theory on Identity Formation

With this in mind, the psycho-social theories on human development of Erik Erikson are the most relevant. For Erikson, the central question of adolescence is one of identity. He labels this stage of development identity versus identity diffusion.

Each stage of Erikson’s theory has a healthy and an unhealthy path that development can follow. The goal is to follow that healthy path. However, in order to better understand successful identity formation, it is useful to examine what the failure to resolve adolescent identity crisis and achieve a stable mature identity looks like. Erikson argues that both identity diffusion and the formation of a negative identity are possible paths that result in the individual failing to resolve the identity crisis inherent in adolescence.

Identity diffusion is an incoherent, disjointed, or incomplete sense of one’s self. Since successful identity formation requires the “unconscious integration of all earlier identifications,” failure to differentiate can lead to identity diffusion because one is unable to complete their sense of self (Schlein 680). Erikson believes that you could also fail to successfully complete the identity stage of his theory if you develop a negative identity. A negative identity is the selection of an identity that is obviously undesirable and rejected by the individual’s community or society.

Since failure to complete the identity formation stage indicates that the adolescents have failed in successfully differentiating themselves from their parents, the successful formation of an identity is dependent on creating a separate and stable identity from all others. This can be seen in the Harry Potter series through tracing the failure of Lord Voldemort and the success of Harry Potter in forging their own identity.

Early Adolescence (Books 1-3)

The Harry Potter books can be divided into three different time periods: early adolescence, middle adolescence, and late adolescence/emerging adulthood. It makes sense to look at Harry’s identity formation through this chronological time frame; Lord Voldemort’s own journey toward identity formation must looked at through the knowledge reader’s gain about him at the appropriate age for each time period. Books one through three—Sorcerer’s Stone, Chamber of Secrets, and Prisoner of Azkaban—fall into Erikson’s category of early adolescence. Early adolescence is when the individual is first leaving childhood and entering adolescence. During childhood, Erikson claims that the child is “deeply and exclusively ‘identified’ with his parents” (115). Adolescents need to have the foundation of a close identification with their parents in order to eventually begin the process of differentiation needed later in adolescence. It is this differentiation that will lead to the formation of a separate, unique identity.

In order to fully understand how Harry is taking the necessary and healthy steps towards identity formation, one must look at how Lord Voldemort, Harry’s literary double, is taking all the wrong and unhealthy steps. Lord Voldemort is the evil wizard who murdered Harry’s parents and was defeated by an infant Harry. Unlike Harry, who is ultimately able to forge a successful identity apart from his parents, Voldemort stunts his own identity formation growth by never fully moving beyond his parents’ orbit.

Readers learn about Voldemort’s experiences as an eleven year old, the same age Harry is when the series starts, in the sixth book, through a series of memories that Harry views. Voldemort at eleven is an orphan like Harry and feels both abandoned and betrayed by his parents. He is not yet known by the name Lord Voldemort but is instead known by his birth name, Tom Marvolo Riddle. When Tom first discovers that he is a wizard, he asks Professor Dumbledore, the future headmaster of Hogwarts, if his father, the man to whom he owes his name, was also a wizard. At this point, Dumbledore does not know, but young Tom Riddle feels sure that his “mother can’t have been magic, or she wouldn’t have died” (HBP 275). This is not true for it is Tom’s mother that was the witch, while his father was a Muggle (a non-magical person). Tom already reveres magic and feels that it can stop anything, even death. He even already hates his name because he feels only “contempt for anything that tied him to other people, anything that made him ordinary” (HBP 277). When he finally does learn that it was his mother that had magic, Voldemort hates his father’s name even more intensely. He is desperate to be special and becomes obsessed with becoming the most powerful wizard—one that can conquer death. Instead of feeling closely identified with his parents, as Erikson suggests is necessary for the child first entering adolescence, Voldemort immediately pushes away his identification with his parents.

In contrast, Harry idealizes his father, James Potter. The most significant example appears near the end of the third book. Throughout the book, Harry is plagued by dementors, disturbing hooded creatures that suck all happiness from a person until all that is left is that person’s worst memories. The only known defense against a dementor is the Patronus Charm. This charm creates a Patronus, a silvery creature that is a unique representation of the spell caster’s identity, which acts as a shield and can repel dementors. At the climax of the book, Harry, Hermione, and his godfather, Sirius, are cornered by dementors. Harry is unable to perform the Patronus Charm, and just as he succumbs to the dementors, he sees someone in the distance cast a powerful Patronus, which saves them all. Harry at first thinks that he has been saved by his father. Despite knowing that his father is dead, he is convinced that the wizard that saved him was James Potter because “it looked like him” (PA 407). Later after Harry time travels to the past, he finally understands that “he hadn’t seen his father—he had seen himself—” (PA 411). With that knowledge, Harry steps out and casts a perfect Patronus for the first time—a silvery stag that charges the dementors. The manifestation of the Patronus as a huge stag is very important. While Harry is the caster of the charm instead of his father, his father manifests in the form of the Patronus. While James Potter was alive, he could transform into a large stag.

Middle Adolescence

The next three books of the series, Goblet of Fire, Order of the Phoenix, and Half-Blood Prince all fit into Erikson’s middle adolescence category. Middle adolescence is characterized by the period spanning roughly ages 14-17. Harry Potter and his friends are ages 14, 15, and 16 respectively in the books. During this stage of adolescence, identification with one’s parents is not enough, the adolescent must move past it and begin the process of differentiation.

Tom Riddle is locked into a hatred of his parents that he is never able to grow beyond, unlike Harry with the Dursleys. He even creates a whole new negative identity: Lord Voldemort. In addition to a negative identity, Voldemort suffers from identity diffusion. Voldemort’s horcruxes, “object[s] in which a person has concealed a part of their soul,” are the perfect metaphor for identity diffusion (HBP 497). The creation of a horcrux is extremely violent, occurring when the creator murders, thereby ripping his soul apart. This protects the creator, as he cannot die unless all pieces of his soul are destroyed. Voldemort starts this process at the age of sixteen, when he murders his father and grandparents, creating the first of an eventual seven horcruxes. By creating them, Voldemort has ensured that he has a seven-part diffused identity. Adolescents that fail to fully commit to an identity suffer identity diffusion. Voldemort cannot commit to even his negative identity; he fears becoming his parents so much that he creates an identity so diffused he doesn’t even feel it when his horcruxes are destroyed until it’s much too late.

Harry, too, is disillusioned with his father. When Harry is left alone in Professor Snape’s office in the fifth book, he views one of Snape’s memories. Snape was a classmate of James Potter. Harry, who is fifteen, views a memory of James at fifteen. He witnesses his father showing off and seeming to love the attention, something that Harry doesn’t understand. He is particularly horrified when he witnesses his father arrogantly and viciously bullying fifteen-year-old Snape. For the first time, Harry is forced to identify not with his father but with Snape, a man Harry had always disliked. For five years, Harry has wanted to be just like James and now he has to ask himself, “[D]id he want to be…anymore?” (OP 667). Harry is forced to acknowledge that his father is not all that he imaged him to be. Although painful, this disillusionment further allows Harry to break from his identification with his parents.

Late Adolescence/Emerging Adulthood

Unlike the other novels in the series, the seventh book needs to be treated separately. It belongs to Erikson’s late adolescence/emerging adulthood category. Deathly Hallows is the only book in the series where the main plot takes place outside of Hogwarts. As seventeen is the age of maturity in the book, it marks the end of adolescence and the beginning of adulthood for the characters.

Voldemort has been unsuccessful because, unlike Harry, he is unable to let go of his parental identifications. Up until the fourth book, Voldemort has been shown in a state of stunted growth due to his inability to correctly differentiate. In the first book, he is a parasite on the back of someone else’s head; in book two, he is merely a memory; and when he first appears in book four, Voldemort is “something ugly, slimy” with the “shape of a crouched human child” (GF 640). It is only through dark magic that he is able to regain his adult body—magic that relies upon the inclusion of one of his father’s bones, and the entire rebirth takes place over his father’s grave. Voldemort, like Harry, needs his father, but unlike Harry, Voldemort is unable to let go of his identification with his parents, despite, or, rather because of his professed hatred of them. His complete and total inability to differentiate from his parents leads to his negative identity and eventual death. Unlike Harry’s death, he is unable to come back because he cannot let go.

In contrast, Harry finally fully lets go of his parents near the end of Deathly Hallows. Knowing that he must die by Voldemort’s hand in order to defeat him, Harry goes to meet Voldemort in the Forbidden Forest. During this trip, Harry has and uses the Resurrection Stone, a powerful stone “that had the power to recall the dead” (DH 408). Harry uses it and gains comfort from seeing ghostly images of his parents. Though he is scared, he lets go of the Resurrection Stone, dropping it in the Forbidden Forest and allowing his parents to vanish as he meets Voldemort by himself. After the battle is won, Harry states that he “dropped it in the forest. I don’t know exactly where, but I’m not going to go looking for it again” (DH 748). Though it is a way to see his parents again, Harry lets it and them go. This contrasts with the first encounter Harry has with the Potters when he will not leave the Mirror of Erised and Dumbledore has to remove it from him. From book one to book seven, Harry’s identity has stabilized enough that he does not need his identification with his parents any longer.

Conclusion

In conclusion, reading Harry Potter allows one to see characters that complete Erikson’s identity formation stage of development to various degrees. Readers can see characters like Harry, who successfully complete the stage and gain a stable, coherent identity, as well as characters like Voldemort who are unsuccessful. Readers end up with a template of success and failure. Despite the fact that Harry’s world is filled with magic, his problems and quest are not that different from his readers’. His readers will never face Voldemort or dragons, but they will face the same problems of identity that he does. As Victoria Hippard writes, “Harry speaks for us; we have our own versions of his story” (3).

Works Cited

Beach, Sara Ann., and Elizabeth Harden. Willner. “The Power of Harry: The Impact of J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter Books on Young Readers.” World Literature Today.Winter (2002): 5. Print.

Erikson, Erik H. Identity: Youth and Crisis. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1968. Print.

Hippard, Victoria L. “Who Invited Harry?: A Depth Pyschological Analysis of the Harry Potter Phenomenon.” Pacifica Graduate Institute, 2007. Print.

Rowling, J.K. Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets. New York: Scholastic Inc., 1999. Print.

—. Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows. New York: Scholastic Inc., 2007. Print.

—. Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire. New York: Scholastic Inc., 2000. Print.

—. Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince. New York: Scholastic Inc., 2005. Print.

—. Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix. New York: Scholastic Inc., 2003. Print.

—. Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban. New York: Scholastic Inc., 1999. Print.

—. Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone. New York: Scholastic Inc., 1997. Print.

Schlein, Stephen., ed. A Way of Looking at Things: Selected Papers from 1930 to 1980 Erik H. Erikson. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1987. Print.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Excellent summary of the Harry Potter time line. I love how Harry grows up in the books, so do the readers, as a lot of kids have read the books from adolescence to adulthood.

Exactly! One of the great things about the series is that each book increases in reading difficulty—ideally they are meant to be read by readers roughly the same age as the main characters.

The masterful storytelling of this series is what makes it.

I really enjoyed this first book. Great character development and can not wait jump into book number two.

When I read Harry Potter everything was new and shiny…and I was simply awed by this magical place full of magical people.

Reading it was quite an adventure.

J L Rowling is definitely a great writer. For a kids book, it is very engaging for an adult.

I read HP after Hatchet, and I found much more interests in this young adult novel than in that long boring novel Hatchet.

As I hopped late onto the Harry Potter bandwagon, I had my hesitations, yet J.K Rowling’s words, stories and characters just seem to capture you and drawn you in, make you committed to the series as soon as you turn the first page. You are such a part of the wonderfully magical and dreamlike world that she has created, it is of no question to me, why this series is so terribly popular.

The Harry Potter books are engaging, but the reason they’ve been such a success is because the underlying themes, archetypes, lessons, and metaphors are spot-on. That’s also why so many adults love the series. You can analyze HP from any model and the structure holds up, which is wonderful.

Thanks for this analysis; I hadn’t seen the approach and enjoyed it.

The beautiful thing about this series, as you and other have pointed out, is how well it relates to kids and their growth. Like you said…despite this world being filled with magic and monsters, the journey of growth is not all that different between a typical teen and Harry. Recently, I was sent a link to a Ted talk from a a few year ago; this talk highlighted the similarities between popular fictional heroes by showcasing the structure with which the story is told. Overall, it’s a nice, short (4:33) animated segment, and I’ll leave the link here. Great job on this article…terrific read!

http://youtu.be/Hhk4N9A0oCA

I loved all of the Harry Potter books!

Fun, entertaining, easy read. I liked the story and am amazed at Rowlings creativity in creating this whole other world.

I refused to read the first book for years out of pure snobbery….and made myself chew through the first chapter….and then I was hooked. Hooked, I tell you!

Harry Potter was one of the many books I read to my kids, one that stands out.

I usually read books before I watch a movie but with this first Harry Potter book I had the unique experience of watching the movie first. My sister and I were going to watch a movie together but the one we wanted to watch was sold out so we picked Harry Potter instead. I had heard some buzz about the books and stuff but I thought they were children’s books. Once I watched the movie I fell in love, and I knew if the movie was this good then the book had to have so much more detail, so I read the book and I was hooked! This series will forever be my favorite books to read, and I am currently re-starting to read these books (for the seventh or eighth time!)

It’s not until the 3rd book that the series starts to shine slowly. First couple of books are quite likeable, and I thought more about introducing the characters.

J.K Rowling is the best! She creates a whole new world that is so exciting and everlasting.

The books are always better. You understand the character better and Rowling did amazingly with it.

The mysteries of this world is never ending.

Excellent article! I love the Harry Potter books and I think they accomplish something very few series have – aging with their readers.

Absolutely fascinating analysis! Harry Potter is my favorite series, and you’ve brought some new depths of it to light. Thanks for a great read!

Harry Potter is amazing of course! A.M.A.Z.I.N.G!!

I can’t really say much, because what is there. It’s my favorite all time series!!

The books were good, creative, and well written, but I’m not ready to call it the best children’s books ever.

Good essay! I think this is not just a great YA book but it is also (imho) one of the finest books ever written.

Some people think these books are simply childrens’ fairytales about magic and enchantments. In reality, they shape peoples’ lives. Every character represents a different life lesson, and I for one learn new things about people, the world, and myself every time I read them. Harry’s world may be fictitious, but the fact that they affect peoples’ lives is very real indeed.

Some people think these books are simply childrens’ fairytales about magic and enchantments. In reality, they shape peoples’ lives. Every character represents a different life lesson, and I for one learn new things about people, the world, and myself every time I read them. Harry’s world may be fictitious, but the fact that they affect hundreds of lives is very real indeed. Very well written and interesting article.

Great article, makes me nostalgic of the books, I want to read them again! identity is such a popular theme in literature but JK Rowling was able to give her own twist to the ‘journey towards identity’ novel and made it unique.

I’ve never read the series and I think it’s about time that I did.

I decided I need to read these books since I have enjoyed the movies so much.

Loved it! They did a great job with the movie, hardly changed a thing!

I’ve read Harry Potter multiple times and each time it still keeps the excitement.

I’ve read the complete series of Harry Potter, as well as watched all the movies. It is safe to say that your connections with searching for identity is a solid take on the series. It is particularly interesting for those who grew up with the Harry Potter series, such as myself. I was the same age as all the actors within the movies, and it was a clever way for J.K. Rowling to sell these movies to a targeted audience of pre-teens to young adults. It is always interesting to read a psychological analysis of a famous book series, and this one is no exception. Well done creating this article.

I loved this! I have seen all the movies, but had not read any of the books. I am so glad I did.

Harry Potter is one of the best bildungsroman I’ve ever read.

– Yours, Mac

I think the mythological aspect of the Harry Potter series makes this series of particular interest. Rowling has tapped into the collective unconscious through her archetypal portrayal and it is the human ability to relate to such subjects that makes the series impactful.

I first read all of the Harry Potter books at the age of 25 and was surprised at how appealing they were for me, even as an adult. I had turned my nose up at them as a teen because I was a “Lord of The Rings guy” when it came to fantasy. I’m glad the movies came about because they were definitely the gateway for me to tackle the book series. This is a pretty great and thoughtful study of Harry’s maturation through the series.

Very interesting article. I never saw it that way. It’s interesting how identity formation is tied to the parents. I think a little more clarity on how this process works is needed, but very fascinating nonetheless. I wonder what Psychoanalysis would have to say.

I really enjoyed this article. I’ve never thought of the story in terms of Erikson’s stages, but it makes a lot of sense.

As both an individual and writer, the HP series had a huge impact on my thinking. I started reading HP when I was around 10 or 11 and grew up with it. Must’ve been around 15 when the seventh book was released and 18 when the final movie came out. My first attempts at writing were with HP in mind (identity formation alongside a book… who knew, right?). And now to go back with this sort of thinking (which is a great analysis alongside Erikson) and examine the series brings back all the joy that I remember when first reading it. Now a graduate lit student at NC State, and I can say that I’ve definitely written about HP for class assignments.

Thank you so much for this article. I grew up reading Harry Potter and this insightful analysis using psycho-developmental theory makes me buzz with joy. I think it’s important you bring up the how Harry de-idolizes his father after witnessing Snape’s memory. Harry had to do the same thing with Dumbledore, a strong father figure throughout the series. Also, the explanation of the horcruxes representing Voldemort’s dispersed identity makes perfect sense in light of things. Harry throughout the series is forming his sense of self, coming to a whole. When he arrives at a concrete, personal identity, Voldemort is at his most fragmented. Harry comes full circle, returning to the scene of trauma where his parents were murdered nearly two decades ago, and reenacts the primal scene. Now I want to further explore a Freudian analysis of Harry Potter!

I’m a B.A. Hons English Literature & Langauge student in the UK, having to do a presentation on Harry Potter. My section is to do with identity in Harry Potter and this was so helpful!

Interesting relationship you developed between Erikson theories and Harry Potter.