Holocaust YA Literature and the Indomitable Feminine Spirit

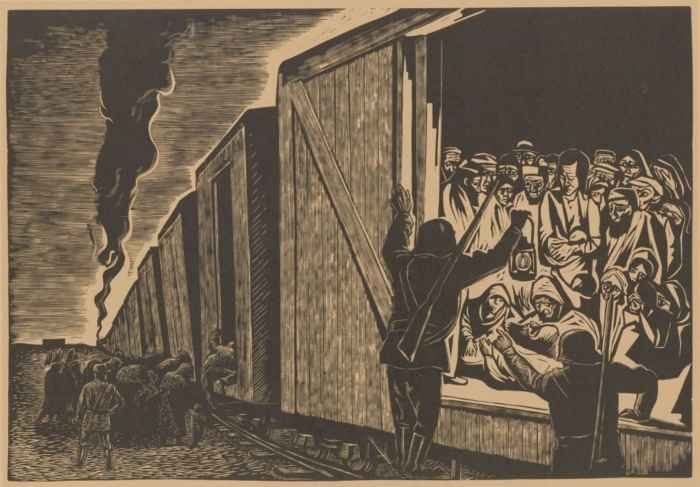

Between 1938 and 1945, Adolf Hitler authorized the extermination of about 11 million people, six million Jews and five million people from other groups he considered “undesirable” or “unfit to live.” These groups included Roma, homosexuals, political prisoners, people with disabilities, and Jehovah’s Witnesses. Victims of Hitler and his S.S. associates, AKA “Death Heads,” were usually worked to death or gassed in concentration camps such as Auschwitz, Bergen-Belsen, and Dachau. Others perished in smaller, lesser-known, but just as notorious camps such as Ravensbruck, Sobibor, or Terezinstadt.

The fact that anyone, male or female, lived is an eternal testimony to the human spirit. However, many of the most popular examples of Holocaust YA literature star young girls or women. This may be because the authors of these books are or were female. It may be because, at least in some cases, the experiences of female concentration camp inmates were more diverse than male experiences. It may stem for the desire for female representation.

Any of these reasons are good. Depending on who you ask, any or all of these reasons might be correct or not. Regardless of the reasons, the indomitable feminine spirit found in YA Holocaust literature today is undeniable. The heroines found in these books can inspire, and have inspired, males and females, especially students just learning about this atrocity in world history. These young girls and women, fiction or nonfiction, have ensured their triumphs and the triumphs of others are not forgotten. They also provide unique cautionary tales, so that an event as deeply evil as the Holocaust may never occur again.

Our discussion will focus on Holocaust YA fiction rather than nonfiction or memoir, for a few reasons. First, fiction gives authors more freedom to explore different facets of a time period, especially a complex one like the Holocaust, even if the authors themselves don’t have first- or secondhand experience with every facet or are not from a certain people group. Perhaps more than any period in history, the Holocaust brought many types of people together, from Jews to Gentiles, from able-bodied to disabled, from Aryan to non-Aryan, when they otherwise might never have met. Eleven million people are gone, and all their stories wait to be told, perhaps in fiction but as respectfully as possible.

Also, the young adults these books are aimed at have probably studied more fiction than nonfiction in their literature classes–or, failing that, they may be able to enjoy and relate better to fiction. Young adults are often just learning, or have already learned, to analyze fiction for themes, motifs, symbols, and other important messages the authors may be trying to communicate. Fiction allows them to explore not only these conventions, but the lessons inherent in Holocaust literature, without feeling like they are being preached at or lectured to in a heavy-handed manner.

Finally, we will discuss fiction over memoir because the Holocaust was and is such a graphic, intense subject. Many young adults have already had intense experiences, but few if any can quite wrap their heads around Nazi atrocities, especially after a first or second exposure. There’s not a twenty-first century frame of reference for this type of thing; some partial references exist for certain young adults (e.g., being a refugee, being persecuted for one’s religion), but not on a Holocaust scale. Fiction, then, gives young adults a “safe” way to interact with the period and start thinking deeply about not only what they would do in those situations, but what they will do when their ethics, morality, or faith is tested as they grow up.

Annemarie Johansen, Number the Stars

First published in 1989, Number the Stars is one of the oldest Holocaust YA novels. It won the 1990 Newbery Medal and is still read in schools, libraries, and homes around the world. The short, powerful novel has been translated into almost every language from Hebrew to Hungarian. Its protagonist, ten-year-old Annemarie Johansen, is partially based on a friend of Lowry’s named Anneliese, who provided some critical historical background and research for the manuscript. Annemarie has a Jewish best friend, Ellen Rosen, who is not a point of view character but is a vital deuterotagonist.

Interestingly, Number the Stars never uses the words “Holocaust,” “concentration camp,” “extermination,” or anything similar. It is in fact the most non-graphic and “innocent” book in our discussion. This might be because Annemarie and Ellen are only ten; Lowry might have thought this age was a little young for graphic detail. Yet something Lowry says in her author’s note disputes this idea. Lowry notes that ten-year-olds are “developing a strong set of ethics” at their age and “want to do the right thing.” Annemarie and Ellen, she hints, are no different. Whether or not they, or real Danish children, knew the harsh realities of the concentration camps didn’t matter so much. What mattered was, these children and the adults around them recognized the crux of the issue behind Jewish “relocation” and “extermination.” Namely, it is wrong to do this to one’s fellow humans, and thus, the wrong must be righted to the best of everyone’s ability no matter how, when, or where it is enacted. The concept may sound basic, but it’s a crucial one, especially for Annemarie, who has been fairly sheltered from Nazi atrocities at the story’s outset and must make her own ethical and moral choices for the first time.

Sisterhood, both biological and “adoptive,” becomes the first way Annemarie, Ellen, and their family fight back against the Nazis, giving Number the Stars its feminist underpinnings. Shortly after Jewish neighbor Mrs. Hirsch disappears from town, Ellen and her family learn their rabbi has been forced to turn over his synagogue member roles so the occupying soldiers can “relocate” and “get rid of” all the town’s Jews. Annemarie’s parents agree to hide Ellen in their apartment, and Ellen assumes the name Lise Johansen, which once belonged to Annemarie’s deceased older sister. The girls had been as close as sisters before the story began; now they must use that bond to protect Ellen’s life.

Not every moment of this sisterhood charade is serious. Ellen continues sharing secrets, playing paper dolls, and enjoying time with Annemarie when she can, which arguably keeps her from being irrevocably traumatized. The two older girls often tell fairy tales to Annemarie’s five-year-old sister, Kirsti, allowing them to revisit simpler and more innocent parts of their childhoods. All three girls commiserate over the deprivation of war and daydream about luxuries like shiny black leather shoes and pink-frosted cupcakes. When it’s time to test the sisterly bond however, Annemarie comes through like a champ. The same night Ellen “moves in,” Nazi soldiers muscle into the Johansens’ apartment, looking for Ellen and her parents who have “disappeared” (the adult Rosens had to take refuge in a different location). Ellen is wearing a Star of David necklace at the time, a dead giveaway to her real identity. She never takes it off, so she can’t undo the clasp. Annemarie must rip the pendant from her friend’s neck and has no time to hide it anywhere but in her clenched fist. When the Nazis leave, satisfied that Ellen is really Lise, Annemarie looks down and notices the Star of David is now an imprint on her palm. Ellen may not be her sister by blood, but in this moment she has claimed a Jewish “sister” for the rest of the book and maybe the rest of her life. Somewhat unknowingly, she has also committed to standing up for the oppressed Jews around her no matter the cost.

The imprint scene is far from the only one in which Annemarie and the Johansen women pit their feminine smarts and human spirits against the Nazi regime and win. Throughout the book, it is usually the women and girls who take heroic actions, even if they don’t know it. For example, little Kirsti is not completely “in” on the secret of why Ellen is with the Johansens because she’s young enough to blow the older girl’s cover without meaning to. However, she gets a crucial if somewhat comedic moment when Mrs. Johansen must take all three girls on a train to Uncle Hendrik’s house so he can use his fishing boat to get Ellen and other Jews to the safety of neutral Sweden. A soldier stops to inspect their tickets and “chat,” presumably looking for information on Ellen. When Mama tries to say she has three daughters with her, Kirsti pipes up to interrupt, and Annemarie fears she will reveal it is “Ellen’s New Year,” Rosh Hashanah. Kirsti actually makes a cute comment about going to see Uncle Hendrik and showing him her brand new shoes, which makes the soldier chuckle and move on. Later, during the climax, Annemarie will take a cue from Kirsti and act like “a silly little girl” who doesn’t know anything when the Nazis stop her during a Resistance-related delivery to Uncle Hendrik’s boat.

Annemarie, Ellen, and even Mama and Kirsti find their courage and loyalty to the Jews tested several more times throughout the novel. Ellen is safely smuggled to Sweden, but she must face her fears to get there, traveling in a locked casket with her parents and another Jewish couple with a baby. It’s not outright stated that Ellen is claustrophobic, but the fact that she knows “relocation” means “disappearance” may indicate she’s scared of being locked up or sent away from her home in any context. Meanwhile, soldiers nearly catch Mama in the forest on the night she and the rest of the family help the Rosens escape. She gets away, but breaks an ankle in the process. Rather than give herself up or even lie to the Nazis who might encroach, she stays in the woods and crawls back to Hendrik’s farmhouse once it is safe. She’s just in time to send Annemarie on an urgent Resistance errand that, if not completed, will spell doom for the Rosens and those traveling with them. Although terrified, Annemarie agrees to “run as fast as [she] can” to make the delivery of a drugged handkerchief that will throw police dogs off the Rosens’ trail. In that moment, she symbolically takes up the mantle of Lise, who was run down on a similar errand a few years earlier. Annemarie chooses courage and righteousness when she could have been “a silly little girl” and risked others’ lives to keep herself safe. She transitions from girl to woman almost seamlessly. No one acknowledges this outright, but it’s clear that by the end of the story, she’s ready to be trusted with the fullness of what it means to resist. We’re meant to think Ellen, although safe in Sweden, has learned this lesson too, and that Kirsti will be more than ready when she begins to form her own set of ethics.

It might seem odd to place Number the Stars, with its short plot and elementary-aged protagonists, in this discussion, but these elements actually make it a perfect book with which to begin. Parents, teachers, and other adults usually want to shelter children from the harsh realities of their world, including evil like the Holocaust, as long as possible. Annemarie, Ellen, and especially Kirsti are in fact sheltered to varying degrees. Yet these young girls are often just as heroic as the adults in their story, if not more so. Women and girls were particularly undervalued and maltreated in the Nazi regime; one line in Number the Stars gives a subtle nod to the anti-feminist expectations placed on German women, such as birthing “perfect” babies for the Fatherland. (Note that many countries, before and after the Nazi regime, are called the Motherland). The idea of a couple elementary-aged girls outsmarting the Nazis and preserving concepts like sisterhood and feminine power might be laughable, even to modern audiences. Annemarie and Ellen’s journeys then become a somewhat understated but poignant, enduring example of what women can do despite a lack of clout, if they band together. They might end up saving an entire people group and in their own way, entire countries.

Hannah Stern, The Devil’s Arithmetic

At face value, Hannah Stern couldn’t be more different from Annemarie Johansen, and not just because she’s three years older and Jewish. Hannah lives in twentieth century New York, outside the immediacy of the Holocaust and Nazi rule. Being Jewish isn’t important to her; if anything, her heritage grates on her. When readers first meet her, we find Hannah complaining about attending the family’s Passover Seder. She has some typical and understandable if immature reasons–she and her little brother will be the only kids there, and they’re likely to be fussed over, thanks to elderly relatives. However, Hannah’s real problem comes from her Grandpa Will, who has extreme reactions to any mention of the Holocaust. At a Stern gathering, one is likely to find him doing something like sitting in front of the TV watching period documentaries, “waving his fist and screaming at the screen,” the numbered tattoo on his arm also waving for all to see. While remembering this and similar outbursts, Hannah also recalls a moment when she was little and inked a meaningless string of numbers along her inner arm to try to imitate, and get close to, her grandfather. Grandpa Will grabbed her up and began screaming, “Malach-ha-mavis” (angel of death). No one could explain to Hannah what she did wrong, and it took a while to calm Grandpa down.

Again, it’s understandable that a young teen like Hannah would be distant from her grandpa after growing up with his traumatic fallout. What stands out though is that Hannah, in her immaturity, lacks empathy for not only her grandfather but the Holocaust itself. Some other family members are also survivors, but Hannah doesn’t understand why they can’t seem to get past that point. “There aren’t any concentration camps now,” she complains to Mom, “so what’s the point of remembering?” Taking this further, Hannah doesn’t see the point of Jewish heritage or ritual, period. She mocks the custom of opening the door for Elijah during the Seder, saying it’s “for babies,” and only seems concerned about getting watered wine during dinner, thus proving maturity. But when Hannah opens the door under gentle duress, she finds maturity, Jewishness, and the Holocaust are not at all what she imagined they were.

Hannah is transported to Poland, circa 1942, where she is known as Chaya (Hebrew name meaning “life,”) a city girl from Lublin who was orphaned thanks to severe sickness, almost succumbed herself, and now lives with her aunt and bachelor uncle Schmuel and Gitl. At first, Hannah continues in her immaturity, complaining about the sailor dress she’s expected to wear to a wedding, as well as the lack of modern conveniences, while she tries to explain to everyone that she is Hannah, from the future. The stakes to prove her real identity are raised when Nazi soldiers interrupt Schmuel’s wedding to Fayge, insisting everyone go with them in their ominous black trucks. But those around her, particularly girls her age Hannah has met on the way to the wedding, believe she is telling one of many fantastic stories. Eventually, Hannah stops trying to actively convince anyone. As her Holocaust journey intensifies, she loses that luxury. Instead, she must focus on remembering she is Hannah and she has a different life as Hannah.

Hannah and her compatriots arrive at an unnamed camp and undergo myriad humiliations. Many of these, such as forcible hair cutting and shaving, or being forced to strip and shower under strange eyes, are particularly humiliating to the women. Hannah notes once shaving is complete, everybody around her looks the same. Schmuel’s bride Fayge is singled out because she lost an exquisite crown of hair, “so black it didn’t even have lighter highlights,” as well as her wedding dress, a beaded headdress, and earrings. Jane Yolen’s “camera” lingers long enough on these moments to show these women have lost finery and beauty along with their senses of self as wives, mothers, providers, or caretakers. Hannah is devastated to notice once her hair is gone, she loses her modern memories. Over time, her memories “[become] camp memories only,” such that she wonders if she was always Chaya and Hannah was an elaborate dream, perhaps brought on by Chaya’s sickness.

Hannah and other women cling to life, persevering in the camp because they have no choice. This lets Hannah learn some crucial lessons about what it means to survive, moreover, what survival looks like for women who male guards and even female ones like the Blokova might single out as special targets. A lot of Hannah’s growth is thanks to Rivka, a camp inmate who has been incarcerated longer than the rest of the cast. She’s ten, but looks and acts older, and has lost all but her brother to the gas chambers. Rivka teaches Hannah to use code words to get what she and others need. For instance, if someone is sick, Rivka says, “I will organize some water,” meaning steal. She and other inmates refer to the gas chambers as “Lilith’s cave,” and being sent there as being “processed,” because to say the real words would invite mental breakdown. “Knowing the wrong things can make you crazy,” Rivka notes once, and Hannah sees this up close and personal when her new friend Esther becomes a broken shell. Additionally, Rivka teaches Hannah tricks to cope with the dehumanizing nature of the camp, such as assigning meaning to her tattooed number. Both girls’ numbers start with J and 1, so Hannah learns to say, J for Jew and 1 for herself, a sneaky way of re-humanizing. Other numbers have different symbolism; Rivka has an 8, which she uses to memorialize the members of her family. Hannah has a 9, which sounds like German for “no.” She declares to herself and others, “No, I will not die here.”

As time passes, Hannah’s growth helps her facilitate victories for others’ lives and femininity. Not every attempt is a success, but her spirit strengthens with each one. At a crucial point, she learns when the guards come to choose people for the gas chambers, the children under a certain age must disappear, because technically they aren’t allowed in the camp. If a child is discovered, his or her life is forfeit. Hannah joins in warning the children by clucking her mouth, which “[sounds like crazed crickets had invaded the place,” and watches them hide in the garbage heap. At first she’s disgusted, but a flash of modern memory gives her new perspective. She remembers Passover in New York, when little brother Aaron hid the afikomen in the laundry hamper and was proud of his clever trick. What Hannah found gross then, she understands now. The Jewish people are choosing to hide their most precious treasures in unexpected, unworthy, disgusting places to save their lives and their legacies. With this realization, Hannah wades into the garbage heap herself, carrying a newborn baby girl the women in her barracks have managed to hide. She also faces intense, almost motherly, guilt when she’s unable to save a little boy named Reuben. When a guard finds Reuben, he asks Hannah if she is his sister. Hannah denies it, so the guard lets her live. “I should’ve said he was my brother,” Hannah laments, but Gitl and the other grown women are there to help her through the grief. They remind her she saved the baby, and that any survival in this place, especially among the women, is a victory.

Yet it is not until Hannah makes a permanent commitment to honoring lives saved and lives lost in concentration camps, and to remembering her Jewish heritage, that her journey can come full circle. Yolen subtly and cleverly foreshadows this, as Hannah’s camp memories fade and her contemporary ones replace them more and more. On one crucial day, she, Rivka, Esther, and Shifre are performing some “mindless” hard labor in the camp fields when a guard arrives, looking for a few more souls to make up a “full load.” Perhaps hearkening back to her contemporary, liberated self, Hannah immediately protests, “You never take healthy hard workers, that’s the rule.” But true to form, the guard doesn’t care. He “chooses” Esther and Shifre, then deliberates and says, “You, with the babushka…I’ll take you, too.” He points to Rivka and winks at Hannah, intending to spare her, perhaps because he perversely admires her spirit.

What happens next is a split second decision, but one that cries out for the victory of the feminine spirit. Hannah rips Rivka’s kerchief off, ties it around her own head, and begs her to run. “Run for your life, Rivka. Run for your future…and remember.” It means Hannah will lose her life and may never see her home or family again. But in this moment, she finally, permanently makes the mature choice. She can finally see long-range consequences and places human life, heritage, and the good of her people above herself. She’s not necessarily a martyr to the cause of Judaism, but saving one life is an act of unprecedented courage and rebellion for her. In a way, she’s able to save Shifre and Esther, too. As the three go to the gas, she tells them one more story. “In the future, there are Jews still,” she reassures them. These girls, the other women, and the men and children surrounding them, will not die in vain. When Hannah is finally transported back to the safety of contemporary New York, she will remember for all of them, so no one has to be forgotten. As for the women left back in the 1940s, we learn through an epilogue that some survive. Leye, the woman whose baby Hannah saved, is one; her baby was “a solemn three-year-old” at the end of WWII. Gitl, Chaya’s aunt, also survived and began an organization to help survivors and displaced children. She named it after her heroine niece: “CHAYA: Life.”

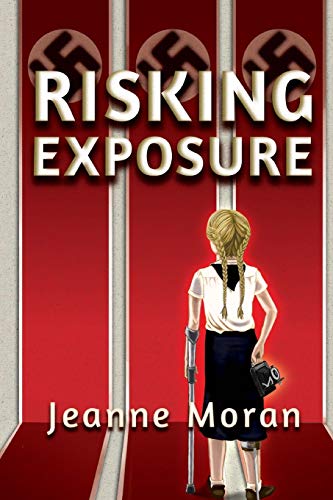

Sophie Adler, Risking Exposure

Jeanne Moran’s Risking Exposure is a more recent contribution to feminist Holocaust literature published in 2013 (with an even more recent sequel that turns more on magical realism). Moran’s work is a departure from our other two books in that it stars a German Aryan protagonist. Sophie Adler is fourteen, living in Munich, and the picture of an ideal German Jungmadel. She’s participating in the female division of Hitler Youth and ready to graduate to the senior troop for girls 14-18. The problem is, Sophie can’t shake a stubborn flu. She has mostly recovered but experiences consistent head and muscle aches. This coupled with her naturally timid personality makes the others in her troop, especially boys like her stepbrother Klaus, underestimate her or outright think and say she’s worth nothing.

Sophie’s insecurity increases as the German kids around her buy more into Nazi propaganda. Her troop leader, stepbrother, and others embrace the idea that the weak or disabled among them are “useless eaters.” Sophie first hears this term when she comes across a litter of puppies on a Bund Deutscher Maedel (BDM) camping expedition. One pup has only three legs, and her mother has rejected her. Klaus and other male Hitler Youth discourage Sophie’s immediate compassion, telling her the pup is better off dead than useless. Sophie’s female troop leader Anna, her friend Renate (Rennie), and other females say and do nothing to contradict this. Their inaction points not only to devaluing of women in the eyes of Nazi Germany, but the fact that they, even strong, hardy, “good” German girls like Anna, are expected to remain silent and subservient.

Throughout the first half of Risking Exposure, Sophie encounters more moments where she could be courageous but chooses timidity and her comfort zone instead. For instance, she shows Rennie the buried pickle jar where she once exchanged notes with Jewish friend Esther Kauffman. Sophie explains Esther’s family was forced out of Munich to a nearby city in greatly reduced circumstances, and Esther has been gone for about a year. Sophie could have said goodbye, but was too afraid to let anyone know she had a Jewish friend. A little later, Klaus catches Sophie with an old note, the last vestige of said Jewish friend. He assumes it’s a note from Sophie’s crush, and Sophie lets him. Her choice cements her current characterization as a silly, spineless little girl only concerned with herself, boys, and social life. After the confrontation, she throws the note out, symbolizing cutting ties with Esther and the Jewish community. On another level, the action symbolizes how Germany and the world at large ignored the Holocaust, not just for the Jews but for the other groups Hitler persecuted.

It should be noted that though Risking Exposure references the Jewish community and Hitler’s Jewish targets, they are not the primary focus for Sophie. That honor goes to the physically and mentally disabled, the first group Hitler and the SS targeted as “life unworthy of life” and “useless eaters.” In fact, the Nazis tested mass gassing and starvation on this population, wiping out at lest 70,000 people. Sophie finds herself with a target on her back when that stubborn flu turns out to be infantile polio. She’s remanded to a hospital and put through grueling physical and occupational therapy. One particularly scary scene shows her terrified of an “iron lung,” a machine whose treatments polio patients underwent when they could no longer breathe on their own. Sophie spends the rest of the book monitoring and counting her breaths, out of fear but also to reassure herself she’s still alive and useful.

Sophie is not targeted for extermination or sent to one of the disguised “killing centers” where the disabled were taken. However, she comes close to painful emotional death a few times, mostly at the hands of other women. Her mother, who was a Nazi supporter to begin with, distances herself from Sophie the longer the latter’s rehabilitation progresses. She visits and does duties such as bringing Sophie clothing and mail, but she doesn’t comfort or bond with her daughter. Some of Sophie’s friends such us Uta and Marie have similar reactions. They visit Sophie, but keep from talking to her much or even touching her, perhaps out of fear she’s contagious. (Polio is actually contagious, but by then, Sophie’s incubation period was long over, and Moran presents the fear more as “catching” becoming useless to Germany). Anna, who becomes Sophie’s junior nurse, is kind to her. Yet her kindness stems more from condescending pity, and a few times she lets slip that Sophie’s disability is undesirable and inconvenient to her. Sophie’s only solace comes from her camera, as she works hard in OT to be able to work it again and take photographs for her country. Anna, Klaus, and others assure her she is not a “useless eater” in their eyes, but the words are hypocritical. Shortly after Sophie gets the assignment to photograph when she is able, Anna tells her she’s been kicked out of BDM because she can’t keep up anymore, even after she goes home.

Despite such a blow, Sophie commits to her photographs, still believing she’s doing something good for Germany. Her resolve wavers when she encounters certain pictures in a military magazine in the hospital’s library. These photos show humiliated Jews forced to eat grass and scrub streets on their hands and knees. Yet the pictures are so horrible, Sophie can’t bring herself to believe her countrymen and women would allow such things. Surely, she thinks, the whole thing is a publicity or festival stunt. Failing that, the footage is badly cobbled or exaggerated. Once again, Sophie retreats behind the “scared girl” mask because to do otherwise is to face some searing truths–yes, her country condones this behavior, and yes, it has rejected her and may at some point consider her unworthy of life. Driving these points home further, Sophie herself is no longer a privileged Jungmadel, but an outsider.

It is only when Sophie’s photos are used against her own “people group” of people with disabilities, specifically women and girls with disabilities, that she’s shaken out of her comfort zone for good. Sophie helps organize a youth talent show to boost morale for the kids at the hospital. Family members, friends, and high-ranking officials will be there; it’s rumored Hitler himself might come. One of the biggest acts is Elisabeth, a fellow polio survivor who used to dance ballet. Elisabeth has progressed enough in PT to do a short dance for the show. Sophie watches the other girl’s rehearsals with a particular mix of pride and hope, and roots for Elisabeth to succeed in the real performance. Elisabeth does, not falling once, and strikes a beautiful pose Sophie captures. Unfortunately, Sophie’s weakness is her action shots. One such shot shows Elisabeth grimacing and bent in an awkward position that hints at ballet but highlights her disability. Sophie is crushed when the Hitler Youth and thus Nazi Party take this shot out of context. They juxtapose it below a shot of “healthy” Hitler Youth boys, with the caption, SHOULD GERMANY’S FUTURE LOOK LIKE THIS…OR LIKE THIS?

Sophie’s new friends at the hospital turn against her, with all-too-willing help from Anna, who blames the whole debacle on her as if it were her idea. But by now, Sophie isn’t willing to hide. She, Rennie, and her crush Erich engineer a plan to get some more photos, including photos that speak the truth of atrocities toward minority groups, into hands of people like a disabled British reporter. The plan is not courageous as a middle grade or YA reader might think of it; Sophie doesn’t actually confront any Nazis with what they’ve done, or rally her fellow patients to riot, or anything of the sort. But actually getting out of the hospital to deliver the photos, on a crowded day when Hitler is in town, requires all Sophie’s inner and outer strength. Her inner strength in particular comes to the forefront, as she purposely ignores being called things like “cripple” and enduring lingering physical pain, to complete her mission. Yes, Erich and Rennie were able to help by organizing and delivering the photos, but Moran makes it clear Sophie is the heroine of the day.

No huge changes occur after Sophie delivers the photos to the reporter, and readers are meant to understand they won’t. The Holocaust and associated atrocities will continue for several more years. Hitler and his associates will continue to mislabel, malign, and persecute anyone that doesn’t fit their narrow mold, including less “obvious” minorities like women. But for Sophie, everything has changed. Her one act of courage matures her into a fully realized, strong woman whose risks still may be more calculated than others’, but who will fight for justice when it counts. She, the “crippled,” fragile “china doll” of the book, the BDM member who was on the outskirts even as a member in good standing, has become the first of her friends to carve an identity outside of what she’s been told is acceptable. She has stood up for girls like Elisabeth, both the ones she knows and the ones who will come after her. Sophie wouldn’t be considered a feminist in the 21st century sense of the word. But her message, that all women are beautiful, skilled, strong, and worthy, is perhaps the most blatant feminist message in our discussion.

Girl Power in the Most Powerless Places

As twenty-first century writers, educators, parents, and people in general, we embrace feminism. We want our daughters, sisters, nieces, and granddaughters to grow up to be strong, well-rounded women who do the right thing and embrace their identities. Why then, would we ever expose our girls to Holocaust literature, wherein women especially were powerless and treated as less than chattel? Perhaps it’s because, paradoxical as it may seem, places like hospitals, concentration camps, and secret annexes are where the human and feminine spirits can grow and shine the most. It might seem there is no choice, but the opposite is true. Every time a female Holocaust survivor, real or fictional, chose to let her spirit live, she took on the unique responsibility of preserving legacies. One legacy was, of course, hers. But every woman who chose life, who clung to life, preserved countless legacies no matter her age, minority group, or unique Holocaust experience. Those legacies continue today through fictional characters who are allowed and encouraged to be whoever they want, and through real authors who bring them to life.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Lovely read. I’ve always had an innate fascination and interest with Holocaust novels, and movies. It started in Middle School with things like history class, a visit to the Holocaust exhibit at the museum, and Number the Stars by Lois Lowry. And it didn’t stop there -it followed me into High School once again with World History, Summer of My German Soldier by Bette Green, and movies like Schindler’s List.

Sophie Adler’s experience with Jewish friends, polio, and the “others” blindly following Nazi orders remind me of what I dealt with growing up with Jewish friends and living with injuries and MS.

Yes I adored the main character within this novel. Sophie is such a strong girl to deal with the pain of becoming crippled due to a disease that fate gave her.

I read Number the Stars compulsively as a child. It was my introduction to the Holocaust.

Number the Stars was such a stressful book! I was so worried for everyone from page one. Lois Lowry has never been an author to waste time on unnecessary words and while I love that about her writing style I do think that held this book back a bit. If she had spent a little more time fleshing out these two families we follow this would have easily been closer to a masterpiece read. That aside this was an important and beautifully written little book, thanks for writing about it.

If you like history and World War II then you should read all of these books – thank you for covering them.

WOW, this is an intense read that I can’t complete in one sitting. Great article!

A good essay about a category of literature I knew next to nothing. Years ago, I had a colleague who survived Dachau and would talk with me about her childhood memories. Your essay brought back some of those conversations.

Number the Stars is such a wonderful read of a family that does everything they can to help friends that are Jewish in WWII. An easy read to remind me of the goodness in people.

I remember reading this book in High School, each month we’d read a different book. Most of them I hated because I didn’t think we were really learning anything, LOL. But before we started to read Number The Stars I went over to my teachers desk and read the back of the book and I was very intrigued by the sound of it.

I didn’t think The Devil’s Arithmetic was a very good historical fiction book. This book was kind of boring and very confusing, I just didn’t find it interesting.

I read The Devil’s Arithmetic after reading The Tattooist of Auschwitz, so the connections between the two books are amazing. This one is a chilling reminder that we cannot forget the past. Excellently written and a true page turner! Your article read smoothly too. Congratulations!

Risking Exposure is a good read but an unsatisfying ending.

I totally love The Devil’s Arithmetic. The story flowed as if a conductor were actually standing before an entire band conducting a piece of music from Mozart.

Stephanie, this was really a great tribute to the importance of remembering the Holocaust.

I will be reading these novels with my students over the next few weeks and will share your article to them as well. Great job!

I admire Lois Lowry’s ability to write for children.

I liked how Lois Lowry included an author’s note at the end to explain what was real and what was fiction; I always appreciate that in my historical fiction.

I read it when I was ten, which is the age of the main character in this book, and I was literally taken back to Amsterdam in World War 2. When Annemarie was scared, so was I. When she felt happy, I did too. Probably one of my favourite books of all time.

There is a lot Annemarie doesn’t know, but she can often tell when something is bad or wrong. I didn’t know of the Nazi occupation of Denmark (or, I guess, hadn’t really thought about Scandinavia during the war), so it was interesting to me to learn about what happened there (and that Sweden, on the other hand, was left alone by the Nazis).

I had never read anything set from the German perspective and reading through the eyes of a young girl in the Hitler Youth truly sold me on Risking Exposure.

A very good story that was spoilt by Americanisms.

Historical fiction based around the Holocaust has always been a genre that makes me slightly uncomfortable, because I feel like some authors are just using the historical setting as a backdrop to make their story interesting.

The books will stick with you forever.

You make an interesting point. I haven’t read the third book you talk about, but I did read the first two, and it’s notable the way those books really do place female characters front and center. There are male characters, of course, but I remember them being fairly marginal and unimportant compared to the girls and women. It really helps to illuminate what the experience of girls and women at that time might have been, as well as how their stories might have differed from those of the men.

These novels are important. Told in a manner preteens can understand, it tells of the horrors of life in the camp.

I read all these books because my English teacher said it was great.

I loved Lowry’s The Giver and always wanted to read Number the Stars. OMG she is such an excellent writer!

A topic like the holocaust is so tough, and there are so many great books that just won’t work for kids (without causing a life long trauma, like the super amazing The Boy in the Striped Pajamas, but for older YA).

An amasing article. Iam a student of Master Translation in Greece and Iam very interested in translating this piece of work in my native language. Please let me know more infos about the writer and her biography, so that I can get in touch with her and get her consent. Thank you

YA fiction about the Holocaust is an important addition to the lives of the next generation. The books themselves may be based on fact and fiction, but this type of material instills curiosity in young minds that thirst for more – thus leading them to the truth of hate and acceptance of cultural diversity.

The stories are quite emotionally intense.