Homosocial Bonding in Marlowe’s Hero and Leander

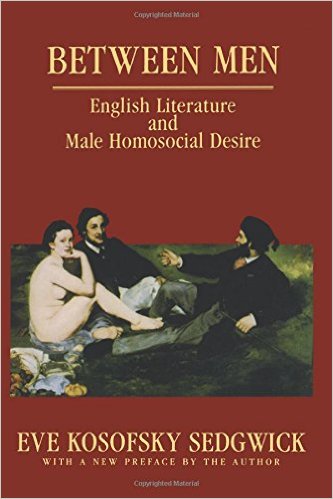

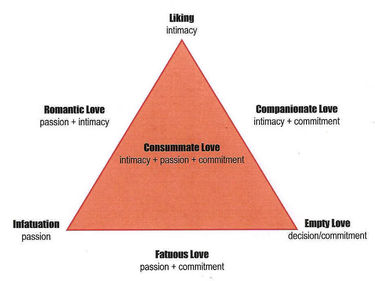

Christopher Marlowe’s epyllion Hero and Leander (~1589) receives immense attention for what has been termed Marlowe’s homoerotic language, specifically when detailing the bodily form of Leander. As opposed to focusing on the poems mythological allusions, evocative descriptions, and ironic wit, readers and critics have placed significant attention on Leander’s encounter with Neptune, which has served as a pivotal angle for interpreting the poem in a homosexual context. Queer theorist Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick utilizes the term homosociality when examining the relationships of males in the mid-eighteenth to mid-nineteenth-century novels in her book Between Men. Focus is placed on male bonding as an acceptable activity, while acknowledging the continuum that exists between homosexual desires and homosocial behaviors (Sedgwick1). Even more fascinating is her proposition that most of the “love triangles,” which she terms “erotic triangles” that exist in literature are important in maintaining gender asymmetry (707). The encounter of Leander and Neptune is not a homosexual encounter, but that of a homosocial interaction that provides Leander with the confidence in pursuing sexual relations with Hero. Neptune provides the balance, as well as the drive for Leander who at this point has been unsuccessful in his fulfillment of a sexual relationship with Hero; once Leander is inspired by Neptune’s incessant desire and suave mannerisms in the act of seduction, Hero finally surrenders to Leander’s unrelenting sexual wishes.

Considerable discussion has centered on the manner in which the characters of Hero and Leander are described. When viewing the lines of verse, it is apparent that the focus is placed on the bodily form of the male character of Leander. Hero’s introduction centers on her beauty due to her immaculate attire, as well as her affiliation with nature. Hero’s ornate attire is first mentioned: “Her kirtle blue…her veil was artificial flowers and leaves…about her neck hung chains of pebble-stone” (15, 19,25). Yet, she is also a figure of nature with her sweet breath that beckons bees, and the sun and wind that dare not inflict harshness upon her beautiful, pale, soft hands (23, 27-8). The juxtaposition between the natural and the synthetic aspects of Hero’s appearance are explicitly stated. Beginning with the considerable contrast represented with the chains of pebbles upon her neck, which alludes to a form of stony realism or even enslavement, as well as the artificial flowers as a reminder that she is not analogous with nature, but her beauty is dependent on man-made constructs. Returning to the chain of pebbles upon her neck, the idea of Hero being a component of a male-dominated world is alluded to, then reiterated in both her beauty being part of synthetic material, as well as foreshadowing Leander’s goal of seduction.

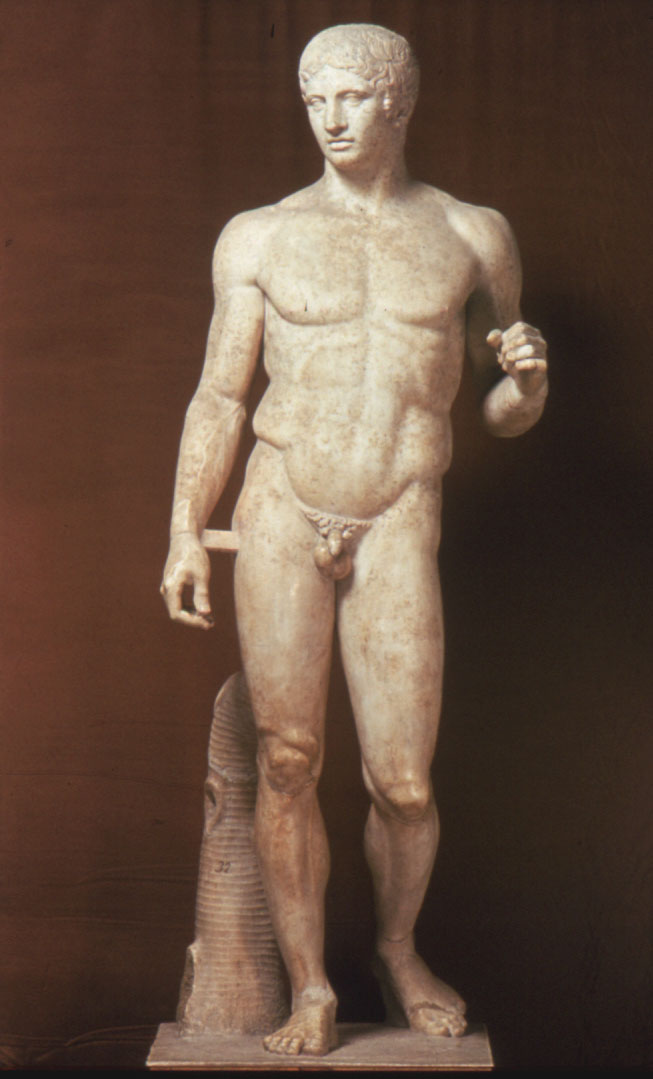

The image of Leander focuses primarily on his bodily form while evoking a tone of androgyny present at varying points in the poem. William Walsh’s article “Sexual Discovery in Renaissance Morality” focuses on the supremacy bestowed on Leander’s description in comparison with the ordinary physical representation of Hero (30). Walsh states that Leander’s depiction is “moved to the world of men,” due to primarily focusing on the reactions of the males who behold his form; whereas Hero’s entrance caused men to basically fall to their feet. There is a divide between the noted reactions of both of these physical beings, and Marlowe’s universal aesthetic description intentionally blurs the gender of Leander (37). According to Walsh, it is due to this genderless description of Leander that causes many critics to cite the homoerotic tone of Marlowe’s poem, which Walsh argues, becomes distracting as it deters from the idealistic love story at the core of the poem. As opposed to viewing the wording as purely sensational and exemplary of homoerotic language, is it not possible that Leander is truly an anomaly in being too pretty for a male? Also, could this form of beauty be the deterrent that at first leaves Hero easily rejecting all of Leander’s appeals for affection?

Leander is first introduced as amorous, beautiful and young, with dangling tresses that were never shorn (51, 55). “Dangling tresses” provides an image of a female form. “His body was as straight as Circe’s wand…Even as delicious meat is to the taste, / So was his neck in touching…How smooth his breast was, and how white his belly, / And whose immortal fingers did imprint/ That heavenly path, with many a curious dint” (61,63-64,66-8). As the lines of verse continue, Leander’s eyes, cheeks and lips are described, constructing a composite illustration or visual of an Adonis like creature. The difference between Adonis and Leander is the virility postulated in discussing Adonis. Referring to a male in this manner is a departure from the majority of literary works. Much of literature tends to the female form more extensively than the male form, but Marlowe does not follow this pattern. The speaker of the poem uses hyperbolic language in regards to Hero, especially pertaining to her ironic association as Venus’ nun; yet the speaker is explicitly enamored with the physical form of Leander.

To accentuate the perfection of Leander’s form the speaker explains the affect his beauty has on those around him. “His presence made the rudest peasant melt…The barbarous Thracian soldier, moved with nought, / Was moved with him, and for his favor sought” elucidating the appeal of Leander even among male counterparts, ranging from the poor, to the barbaric soldier (79, 81-2). The androgynous details of Leander are once again conveyed. “Some swore he was a maid in man’s attire, / For in his looks were all that men desire:” serving as an immense contrast from Hero’s introduction in which she was able to enrapture men with the power of her beauty, enthrall Apollo with her allure, and even blind Cupid with her beauty (83-4). Every one of the individuals affected by Hero are members of the opposite sex, contrary to the reactions garnered from Leander’s appearance. “And such as knew he was a man, would say, / ‘Leander, thou art made for amorous play;/ Why art thou not in in love, and loved of all? /Though thou be fair, yet be not thine own thrall’” (86-90). The manner in which Marlowe begins the epyllion with the descriptions of Hero and Leander sets the stage for the numerous conversations regarding the homoerotic language used in this poem.

Due to Marlowe’s personal sexual preferences, readers and critics alike tend to interpret his poetry as explicitly homoerotic. While there is an aspect of homoerotic flirtation in Hero and Leander in both the description of Leander, as well as the encounter with Neptune, in the end, Leander’s unwavering pursuit of Hero explicitly place this poem in the realm of a heterosexual love poem. Jonathan Culler’s Literary Theory contains an excerpt from Judith Butler that describes language as the manner “for thinking about crucial social processes” (106). Due to the numerous critical articles dedicated to the “homoerotic language” of Hero and Leander Butler attempts to stress the manner in which literature is interpreted by readers, according to social mores of the zeitgeist. Haber postulates the importance of separating the actual work from the author’s biographical information as a means of thwarting misperceptions of literary works. The abundance of articles devoted to Christopher Marlowe’s sexual preferences influences readership and interpretations of this poem in a different manner from his predecessors, Ovid and Musaeus. Haber distinguishes the fact that these previous poems are not perceived through a homosexual lens of introspection, which reiterates the problem of Marlowe’s private life disrupting an objective reading of his epyllion.

Marlowe utilizes satirical language and comical similes to express Leander’s unwavering pursuit of Hero. An initial example is Leander’s endeavor to convince Hero, (also referred to as) Venus’ nun—an example of ironic humor—that remaining chaste will lead to a life of discord and bitterness. In attempting to impress this notion on Hero he states, “Like untuned golden strings all women are, / Which, long time lie untouched, will harshly jar” (229-30). The simile “like untuned golden strings” is Leander’s attempt to persuade Hero that her virginity is not something she should covet. Leander tells her to embrace sex, and to not remain like the untouched strings, forever emitting harshness due to never being sexually intimate. His attempts center upon the enticement of manipulation in the same manner as an instrument—woman—should be handled and possessed. Building upon this theme of withholding form sexual delight in favor of remaining pure, Leander begins to build a stronger case as to why Hero’s actions are not only frivolous, but also depraved.

Abandoned fruitless, cold virginity,

The gentle Queen of Love’s sole enemy.

Then shall you most resemble Venus’ nun,

When Venus’ sweet rites performed and done.

Flint-breasted Pallas joys in single life,

But Pallas and your mistress are at strife.

Love, hero, then be not tyrannous,

But heal the heart that thou hast wounded thus,

Not stain thy youthful years with avarice;

Fair fools delight to be accounted nice. ( 317-25)

Leander begins to take on a harsher tongue when addressing Hero’s determination to remain chaste when referring to her as selfish, as well as greedy. Withholding her maidenhood from him, according to Leander, places her in the realm of a tyrant, denying her deity, Venus, while abiding by the goddess of war, Pallas. Leander’s appeals are outlandish and paradoxical when inverting vice with virtue. As opposed to treasuring female chastity, Leander equates it to a means of depravity and greed. Though this is a melodramatic comparison, Marlowe is conveying the feelings of distress experienced by Leander who is enamored with Hero and cannot understand her decision to not reciprocate his affection.

As the lines of verse continue, Leander becomes more assertive in his attempt to convince Hero to give her body to him. An example occurs when he states that “One is no number, maids are nothing then, / Without the sweet society of men. /Wilt thou live single still? One shalt thou be, /Though never-singling Hymen couple thee” (255-8). Leander is equating a woman’s worth as dependent on a man’s companionship; a single maiden is a non-entity without male companionship to provide her with status. He then, once again utilizes another simile describing the perverse decision to remain chaste in a comical tone when juxtaposing virginity to water and marriage to wine. This interweaving of serious comparisons with comical overtones continues for numerous lines of verse. At one point, Leander explains that the act of remaining chaste is not an honorable act, as honor is earned when one engages in a great deed. He continues his argument against chastity with the mention of Venus, the goddess of love whom Hero associates herself with, as well as Diana, the deity of chastity. The term Venus’-nun is derived from Marlowe’s satirical use of the goddesses, and Leander’s accusations that Hero’s chastity is sacrilegious against her deity (Venus) and further insults her decision by comparing her virginity to an act of iniquity.

Leander’s appeals for Hero’s virginity are unsuccessful until he encounters Neptune and engages in a form of homosocial bonding that revitalizes Leander’s vigor, and results in the successful sexual acquisition of Hero. Queer theorist Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick introduced the term homosocial bonding in her book, Between Men. The idea of homosociality derived from her research of literary texts from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries that reflected forms of homosocial bonding—male friendships, mentorships, and entitlement—reflective of the social, economic, and ideological changes taking place at the time (Sedgwick 1). Shifting ideas of class played a significant role in the pattern she observed, as did the relation to women, as well as the gender system (1). Sedgwick explains that homosocial desire is a type of oxymoron, describing social bonds between people of the same sex. “It is a neologism, obviously formed by analogy with ‘homosexual’” (1). Her intended goal is to distinguish between deeming all interactions between members of the same sex as deriving from sexual desire, but instead to recognize forms of homosocial bonding. Due to the paradoxical relationship between heterosexual and homosexual relationships Sedgwick highlights the dichotomous continuum that exists as a way to avoid homophobic assumptions, most prevalent amongst male relationships (2).

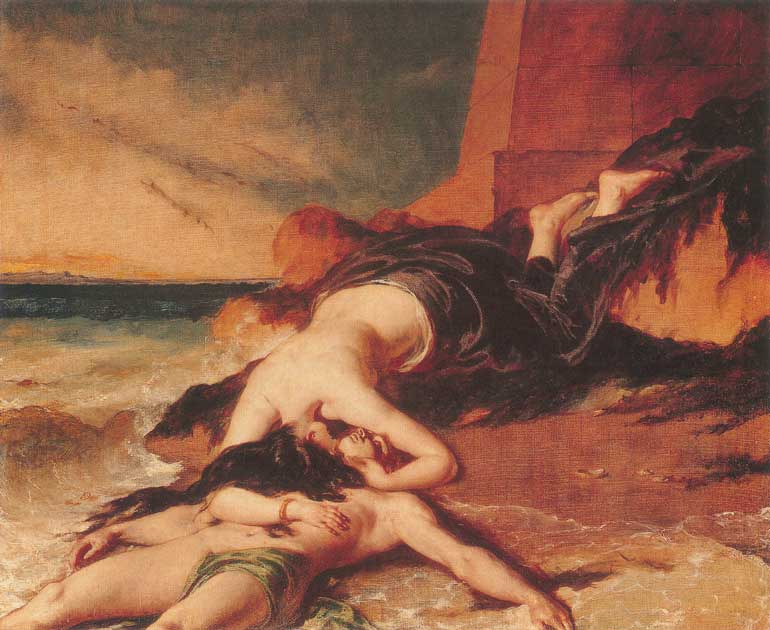

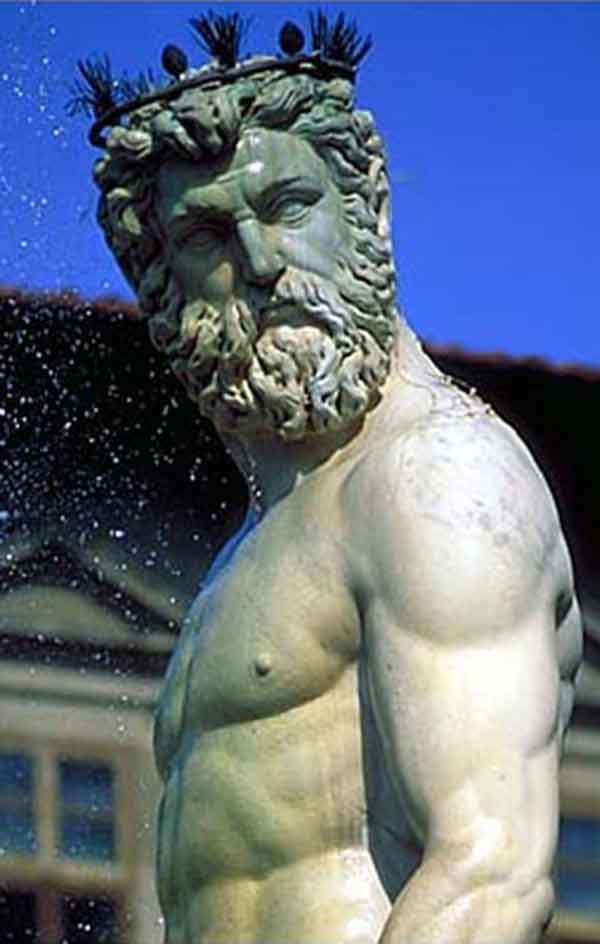

When Leander first encounters Neptune, the immediate feelings expressed by Neptune are of sexual desire due to mistaking Leander for Ganymede who was once his lover.

The lusty god embraced him, called him love,

And swore he should never return to Jove.

But when he knew it was not Ganymede,

For underwater he was almost dead,

He heaved him up, and looking on his face,

Beat down the bold waves with his triple mace,

Which mounted up, intending to have kissed him,

And fell in drops like tears because they missed

Him. (Marlowe 650-9)

Interestingly, the similar drive between both of these males is their desire to be with the one they love. Leander shouts, “Love I come!” before leaping into the sea to swim to Hero’s home in Sestos, and Neptune embraces Leander (whom he has mistaken for Ganymede) while calling him love (638). Leander does not realize that Neptune thinks he is Ganymede, but instead believes he has been mistaken for a female, “Leander made reply, / ‘You are deceived, I am no woman I’/ Thereat smiled Neptune, and then told a tale” (675-7). Though, at this point, even though Neptune realizes he is not Ganymede, he is still enthralled with Leander and recounts a tale of a seduction that takes place between a boy and a shepherd. He then engages in a game of flirtation with Leander ignores due to a sole interest in reaching land, which greatly upsets Neptune. At first, Neptune considers inflicting wrath against Leander, but then decides against doing so out of love, and assists Leander in his retreat to shore.

Neptune’s desire remains heightened even after realizing Leander’s identity due to an attraction to Leander’s undeniable aesthetic appeal. Edmund Burke discusses the power of aesthetic beauty in Chapter X of A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of our Ideas of the Sublime and the Beautiful. The attraction towards Leander, exhibited by Neptune, is purely physical and derived from aesthetic appeal. He also experiences sentiments of tenderness and affection in a sexual manner based on the common laws of nature that are not parallel with the mores of society (27). According to societal standards, a male should not desire another male, but Burke describes the power of aesthetic appeal in thwarting the senses and evoking sensations that are more powerful than social conventions. Due to Neptune also being a deity, he does not abide by the laws of society; Leander does not acquiesce to Neptune due to being completely enthralled with the aesthetic beauty of Hero. Burke continues the discussion with the topic of socially acceptable couplings that lead to heightened feelings of attraction. For example, two individuals from the same class will feel a connection due to sharing similar social qualities (27). Hero and Leander is a socially acceptable couple; whereas Leander and Neptune defy what society deems “natural.”

Sedgwick reviewed literature from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries to observe male bonds that had been constantly referred to as conveying homoerotic undertones. Male bonding, according to Sedgwick, should not be viewed as homosexual activity, but observed as moments of mentorship and camaraderie (Leitch 2467). Queer and Gender theorist attempt to provide a contemporary lens to earlier works, as well as distinguishing actions from previous centuries within a historical context. The manner in which modern society explicitly distinguishes relationships and actions based on current ideologies leads to flawed interpretations. Sedgwick stresses the importance of the continuum between homosexual and heterosexual desires to divert discrimination. There is a distinct, discriminatory interpretation of Marlowe’s work that places immense emphasis on the physicality of males, as opposed to the events transpiring between the title subjects of the poem.

The encounter between Neptune and Leander is a pivotal example of homosocial bonding in which Neptune’s sexual prowess of Leander serves as a role model for Leander’s sexual pursuit of Hero. Building on her previous establishment of homosociality, Sedgwick also discusses the idea of gender asymmetry also known as erotic triangles. The erotic triangles are similar to love triangles that exist amongst characters in literary works. The relationship between characters entangled in such matters is integral to maintaining a form of homeostasis and a continuation of the actions of the poem. As Sedgwick posits, “the bonds of love and rivalry are equally powerful” (708). In Hero and Leander the erotic love triangle consists of: Hero, Leander, and Neptune. Hero and Leander’s relationship remains stagnant until Leander encounters Neptune. This pivotal encounter becomes the moment the epyllion is contingent upon due to it evoking a new sense of bravado in Leander’s mind, and a resolute decision to make Hero his lover. Though she has opposed all previous attempts, Leander approaches the situation with the same insistence, cunning wit, and unwavering desire that had just been exhibited to him by Neptune.

Returning to Sedgwick’s suggested key components of the love triangle: rivalry and love, the rivalry exists amongst Neptune and Hero, whereas the aspect of love functions on a continuum between all three characters, in a primarily unilateral manner. Neptune, a god, experiences feelings of wrath when rejected by Leander who vocalizes his ultimate goal of seducing Hero. Neptune’s decision to save Leander from drowning occurs due to an aesthetic appreciation for Leander’s beautiful bodily form and a sensation of love. As for Hero, she is the unknowing rival of Neptune, due to being unaware of the situation preceding her night with Leander; yet Neptune is very aware of Hero serving as a distraction to his desired conquest. Hero does love Leander but spends the majority of the poem rejecting all sexual advances. Her resolve of abstinence diminishes after Leander’s encounter with Neptune, due to Leander’s newfound ability to exude suave mannerisms and incapacitating all of Hero’s previous resolve. As for Leander, he is the sole component of the triangle whose love functions bilaterally. He experiences passionate love for Hero whose body he seeks to possess, while he feels a homosocial bond towards Neptune who has equipped him with the ability to finally achieve his goal of Hero’s love and body.

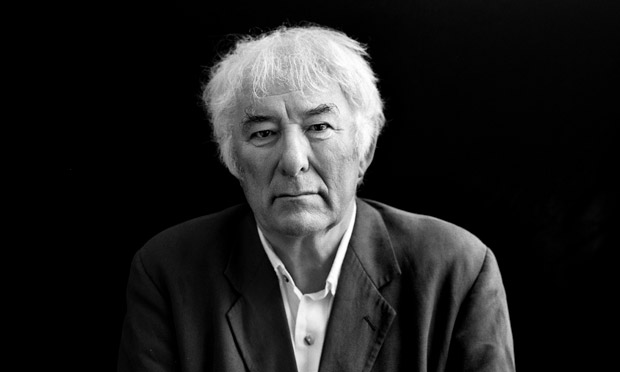

One of Marlowe’s staunch advocates, Seamus Heaney, presented an Oxford Lecture on Hero and Leander supporting the language and freedom represented in the beauty of the speech, which is free of social conventions. To begin his argument “On Christopher Marlowe,” Heaney notes that the sexualized language garnering immense interest in this poem dated back to Ovid’s Amores, as well as the Imperial Roman vie de boheme (35). As opposed to viewing the poem in a homoerotic manner, the freedom of sexuality, according to Heaney, should be appreciated and embraced, though he notes this is a difficult task in a world filled with numerous social conventions. “The motion of the soul, then in “hero and Leander” is forward towards liberation and beatitude but it is a motion hampered by a countervailing acknowledgment of repression and constraint” (37). The constraint and repression discussed by Heaney derives from both the exuberant description of Leander’s body, as well as his encounter with Neptune. Interestingly, the androgynous manner in which Leander is described, according to Heaney, is a foreshadowing of Leander’s eventual encounter with the “befuddled sensualist,” Neptune (37). As opposed to focusing too much attention on what is commonly termed “the episode” (Neptune’s attempted seduction of Leander) in Hero and Leander, Heaney utilizes the syntax and formal rhyme scheme of the poem to reiterate the sole attraction Leander feels towards Hero—not Neptune. “The gender of the love that he is demurring from is being simultaneously confirmed by the gender of the rhyme” (38). Though he mentions the earlier description of Leander as “androgynous frolics” the consistency of the feminine rhyme throughout the poem, reiterates the object of Leander’s desire as the female embodiment of love in the form of Hero (39).

Christopher Marlowe was a passionate man as well as poet whose sexual exploits are just as popular points of discussion as are his numerous literary masterpieces. Hero and Leander does toy with ideas of same-sex appeal, but the heightened manner in which these points are discussed are clearly due to knowledge of Marlowe’s personal sexual preferences. The description of Leander in the beginning of the epyllion is excessively centered on his body, but then it should be considered that Hero’s description contains hyperboles with men dying at her feet after beholding her beautiful form. Marlowe attempts a “tongue-in-cheek style” while also integrating beautiful lines of verse. As for the Neptune and Leander scene, the sexual desire is unilateral, as Leander is solely enraptured with Hero. This is where Eve Sedgwick’s theory of homosocial bonding fits nicely in explaining homosocial relations. It is through the modeling of sexual bravado by the confident Neptune that Leander is able to acquiesce the virginity of Hero. Further progressing the verse is the erotic triangle between Hero, Leander, and Neptune, in which the actions towards Leander (by Neptune) move the poem from a position of stagnation to progression. Leander’s conquest becomes undeniable as he swims upon the shore and beds the woman he desires. Though Neptune is left in a state of disappointment and feelings of rivalry towards Leander’s desired female, his love for Leander allows him the strength to invigorate his novice companion, and allow the lovers to unite as one.

Works Cited

Aristotle. On Poetry and Style. Trans. G.M.A. Grube. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing, 1989.

Burke. Edmund. A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of our Ideas of the Sublime and the Beautiful. Mineola: Dover Publications, 2008.

Culler, Jonathan. Literary Theory: A Very Short Introduction. New York: Oxford University Press, 2011.

Heaney, Seamus. “An Oxford Lecture: On Christopher Marlowe’s “Hero and Leander.” Harvard Review, No. 1 (Spring 1992), pp. 35-39. Harvard Review Press. JSTOR. Web. 8 Dec. 2015.

Kitch, Aaron. “The Golden Muse: Protestantism, Mercantilism, and the uses of Ovid in Marlowe’s ‘Hero and Leander’.” Religion and Literature. Vol. 38, No. 3 (Autumn 2006), p. 157-176. University of Notre Dame. JSTOR. Web. 4 Oct. 2015.

Marlowe, Christopher. Hero and Leander. The Norton Anthology of English Literature: Volume B. 9th ed. Ed. Greenblatt, Et.al. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2012. P. 1108-1126. Print.

Sedgwick, Eve Kosofsky. “From Between Men: English Literature and Male Homosocial Desire: Introduction. The Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism. 2nd ed. Ed. Vincent B. Leitch, et.al. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2012. P. 2466-2477. Print.

Sedgwick, Eve Kasofsky. “Gender Asymmetry and Erotic Triangles.” Between Men. New York: Columbia University Press, 1985. Print.

Walsh, Willam P. “Sexual Discovery and Renaissance Morality in Marlowe’s ‘Hero and Leander’.” Studies in English Literature, 1500-1900. Vol. 12, No. 1, (Winter 1972), p. 33-54. Rice University. JSTOR. 11 Oct. 2015.

Weaver, William P. “Marlowe’s Fable: Hero and Leander and the Rudiments of Eloquence.” Studies in Philology. 105.3 (2008): 388-408. Project MUSE. Web. 9 Oct. 2015.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

I have read some, but not all of the works of Christopher Marlowe. He is a contemporary of Shakespeare. I generally find Marlowe more easily read than Shakespeare. This may be because he died young and did not have a chance to mature and evolve as Shakespeare did.

Now that I have read this article, I want to desperately debate this poem in a modern lit class.

Dear Marlowe, we need to talk about the meaning of “no.”

Looney, I find Marlowe’s work to be fascinating…and Looney, you are correct, I, too, believe Marlowe’s work is more accessible than Shakespeare’s. It’s not that Shakespeare isn’t phenomenal, but sometimes the plays feel repetitive, or the subject matter feels too far removed to instill a sense of relatable material.

Dove, I recommend that you do debate this epyllion in a lit course!! You will generate a ton of feedback–both negative and positive–and it will make for an interesting discussion. The scene described between Neptune and Leander is one that divides readers, especially since Neptune mistakes Leander for Ganymede, Neptune’s former lover. Yet, the moment of realization leads to Neptune guiding Leander to the surface…go for it!

Amazing article. Great pictures and analysis.

I have to admit that I remember very little about this one other than I read it for a Renaissance poetry class. Maybe I’ll reread it at aime point.

It’s interesting to see what was considered an “erotic” poem in the sixteenth century. This would be rated PG today!

To everyone interested in further reading once reading this article, you have not read Marlowe’s great works unless you have read HERO AND LEANDER. Do not neglect it.

One of the great narrative pomes of his time and place!

It’s a shame that we do not know if Marlowe did or didn’t intend to finish/write more for this poem!

Weirdly funny, actually. I read his work for years ago. Thanks for reminding me of my favourite poem of his.

The art of seduction. He mastered it.

Had he been given a longer time on earth, Marlowe’s body of work would have rivaled that of Shakespeare’s.

Absolutely beautiful.

Is it just me or does Chris Marlowe really hate chicks? Just my 2 cents.

I recommend everyone to read anything by Marlowe.

I read this for my British Literature I class. Marlowe was undoubtedly a talented writer, and it’s interesting how this story relied on so many aspects of mythology in weaving the tale, but ultimately I viewed this as just another story of two people in lust with each other. I didn’t care for it.

My first time ever hearing about the Hero and Leander mythology. It sounds quite tragic and sad. Thanks for introducing me to it.

Full of passion and it’s extraordinarily lovable. This about time I reread his work.

Hilarious if you understand the elements of its parody.

I thought it was a beautiful piece. The writing is brilliant. Lovely piece of writing you have here too Danielle.

This is quite an innovative retelling of the ancient Greek myth.

Marlowe’s use of imagery is absolutely exquisite.

It may just be the gayest thing ever.

What a strange poem. Before being assigned it for my Intro to British and American Lit class, I had honestly never heard of it or the mythological tale that inspired Marlowe’s pen.

Having only ever looked at homosocial relationships/bonding in Shakespeare (in his comedies, to be more precise), seeing how it appears in Marlowe’s work is fascinating! Great article.

This is a great article with good sources and good use of evidence from the text.

I honestly get stuck a little on the comment about objectivity, though. It’s a comment attributed to Haber (Judith Haber?): “Haber postulates the importance of separating the actual work from the author’s biographical information as a means of thwarting misperceptions of literary works. The abundance of articles devoted to Christopher Marlowe’s sexual preferences influences readership and interpretations of this poem in a different manner from his predecessors, Ovid and Musaeus. Haber distinguishes the fact that these previous poems are not perceived through a homosexual lens of introspection, which reiterates the problem of Marlowe’s private life disrupting an objective reading of his epyllion.”

How is ignoring the author’s biographical information considered a move toward objectivity in our reading of a text? (I understand the New Critical argument about the “intentional fallacy,” but I would not expect to find more recent critics simply repeating that argument.) Couldn’t we just as easily say that refusing to acknowledge the author’s biographical information when it comes to queerness shows a lack of objectivity in how we are reading? To be objective, would we not need to reject all biographical information as well as all previous interpretations of the text for everything we read? And even then, are we not still reading the work through our very own personal (and subjective) “lens of introspection”?

I found this incredibly poignant as I’ve been reading the works of Oscar Wilde in preparation for the costume design for “A Gross Indecency.” The play is a Moses Kauffman piece telling the story of the Aesthetic movement and Oscar Wilde’s roll in it thru pieces of narrative, newspaper clipping, interviews and records from the multiple trials concerning his conviction.

During the second trial, when asked what is “the love that dare not speak its name?” Wilde replied with this answer:

“The love that dare not speak its name” in this century is such a great affection of an elder for a younger man as there was between David and Jonathan, such as Plato made the very basis of his philosophy, and such as you find in the sonnets of Michelangelo and Shakespeare. It is that deep spiritual affection that is as pure as it is perfect. It dictates and pervades great works of art, like those of Shakespeare and Michelangelo, and those two letters of mine, such as they are. It is in this century misunderstood, so much misunderstood that it may be described as “the love that dare not speak its name,” and on that account of it I am placed where I am now. It is beautiful, it is fine, it is the noblest form of affection. There is nothing unnatural about it. It is intellectual, and it repeatedly exists between an older and a younger man, when the older man has intellect, and the younger man has all the joy, hope and glamour of life before him. That it should be so, the world does not understand. The world mocks at it, and sometimes puts one in the pillory for it.”

While a beautiful sentiment, the response was quite counter-productive in the legal sense and only furthered the prosecutors arguments. But this article draws beautiful parallels to Wilde’s notions and the Aesthetic movement in general.

A remarkably poor account of the poem; pretty much makes it up as it goes along. The those chains of pebble-stone around Hero’s neck. Nothing to do with enslavement, but, since they shone like diamonds, part of the hyperbolic and faintly ridiculous description of Hero. And so on.

Daumants, Part of the beauty of literature is the ability to analyze it from numerous perspectives. As for our response, “remarkably poor account of the poem,” I would have to adamantly disagree, especially since your “evidence” citing the poor account is the “chain of pebble-stone.” Relating this to a form of enslavement is not being frivolous with a very serious issue, but pointing to the manner in which one may be “stuck” in a certain preconceived position in life.

As for the “hyperbolic and faintly ridiculous description of hero,” I do believe you should revisit Marlowe’s epyllion, as it is well cited by renowned literary theorists as a gross exaggeration. The roles are reversed; whereas it is usually the woman–Hero–that receives the most attention in reference to bodily attributes, Leander–the male–is the one that is described in a sensual, ethereal manner. I also think you may be mixing up the characters. Hero is the female; Leander is the male, and this was yet another jest on the part of Marlowe (As the male is typically referred to as the male). I am sorry you did not enjoy the article…I hope you find something else more suited to your taste. –Best, danielle577

Hello, I really enjoyed this article and I wish to cite it for use in one of my critical essays. May i please have your full name so I can credit you where necessary. Thanks, Neha

The quote that you provided (255-58) is not a simile as a simile requires a point of comparison (which is not present from what I can tell).

danielle please contact me i want to cite this article but idk who you are… can i have an email or something please i am actually desperate

You can cite this article and the author via their alias here. In this case, it is: danielle577