Classic Literature’s “Infinity Girls”

“Homeless” Millennial Book Girls

As author Sarah Clarkson put it, women who love books today had childhoods wherein they were considered “book girls.” These girls found their truest friends between the pages of books as well as in school or extracurricular activities. Some of them collected books the way other girls collected Barbies or American Girls, Lisa Frank merchandise, or Lip Smackers lip gloss. For many “book girls” of recent generations, the books and series they grew up with still play a big role in who they are today and how they socialize.

In particular, many millennial women align themselves with a book series, or several standalone books, that fostered their love of reading or shaped their childhoods. If a millennial woman loved Bonnie Bryant’s The Saddle Club or Joanna Campbell’s Thoroughbreds series, she was likely a “horse girl.” Another millennial woman might have grown up loving Nancy Drew and styled herself as a “mystery girl” or “girl detective.” As millennial girls got older, many of them gravitated toward books like the Sweet Valley High series, the Nancy Drew Files, The Princess Diaries, or Angus, Thongs, and Full-Frontal Snogging, which bloomed into the Georgia Nicholson series. For grown-up millennial girls, it was not enough to be a “bookworm” or a “book girl.” One needed a series or genre to make her own, a literary “home.”

Some millennial girls did not fit easily into these subsets. Such “book girls” may have read and enjoyed some of the above series without committing to a “fandom.” Similarly, these girls may have enjoyed books popular with childhood peers. Yet “growing into” or relating to the plotlines of series like The Princess Diaries or Sweet Valley High was difficult. The plotlines of such series, geared toward high school students and young adults, are appropriate for young adults, but still edgy. Plus, the fantasy of living the life of a princess, or living in an idyllic Southern California setting as a turquoise-eyed blonde with a perpetually size six figure, is appealing. Yet some “book girls” found the plotlines’ edginess off-putting and the characters within them unrealistically mature, but somehow shallow.

Such an experience with adolescent literature left a small but important group of readers with an interesting “story” of their own. On the one hand, their reading let them form unique identities and understandings of their world. Arguably, those identities and understandings let these bookworms mature faster than their peers, leaving them better prepared for academic, emotional, and social challenges as adults. But these girls did not have a peer group to which they could easily attach themselves. Peers who weren’t deeply interested in books might have shunned them, and fellow bookworms were probably distant.

Therefore, even though girls without a “literary home” didn’t seek a “label,” they did not have a way to identify, style, and craft themselves as their fellow bookworms did. They were homeless, nameless, on the fringes of book world. While some, if not most, were content to “float” to whatever standalone novel or series fed their interests, this was not the same experience as being a “book girl” with a like-minded circle.

Building a New Literary Home

A female Tumblr user, or Tumblrina, recently posed a question about these readers on the site. Paraphrased, she asked, “If the Saddle Club is a direct line to ‘horse girl,’ and books like Goosebumps are a direct line to ‘goth girl,’ what is Anne of Green Gables, A Little Princess, and Little Women a direct line to?'” Like so many other grown-up millennial “book girls,” the Tumblrina sought to discover where her reading experience had led and was leading. She asked the questions, is there a healthy way to embrace that experience and use it to shape who they are as adults, the way more “mainstream” girls have? More importantly, would adult “book girls” who did not find their homes in their peers’ series or groups benefit from doing so now as adults?

These questions have complex answers. Yet they are still easily answered if we examine the books and protagonists these millennial women gravitated toward as children and teens. When we give the books in our discussion close readings, we find the books and protagonists have several key elements in common. Those elements unite, letting each formerly homeless millennial bookworm craft not only her own identity, but her identity within a literary circle. They are the “boards” with which these women can build the “homes” they didn’t have in the ’80s, ’90s, and ’00s. Unlike the “horse girl” or “goth girl” or “mystery girl” home however, these “boards” will likely end up crafting a smaller, yet much more eclectic, home. The nature of the grown-up girls living inside this home means that its foundations may look formulaic enough to fit into the archetype of a millennial series reader. But while this literary home is formulaic in one way, in others, it is extremely complex. It demands much of its residents–one could argue, a lifetime commitment.

The Ultimate Security Deposit

The use of this phrase feels extreme. Adult women who once loved Sweet Valley no longer aspire to find a long-lost twin or live the high-drama lives of Elizabeth and Jessica Wakefield. Women who consumed The Princess Diaries franchise might enjoy it with their daughters, granddaughters, or nieces, but do not expect to be whisked to an unknown European principality and crowned sole ruler. If anything, the idea of an adolescent reading experience is, the reader grows out of it and into something and someone else.

But the perceived extremity of a “lifetime commitment” actually draws the homeless book girls we have discussed, because as adults, they often still struggle with finding ways to channel their interests and feelings. That is, adult horse girls often participate in other sports, or seek out occupations dealing with athleticism or animals, if they don’t own ranches, camps, or equines outright. Adult mystery girls are our police detectives, our forensic analysts, our judges and attorneys. Adults who loved The Baby-Sitters’ Club or The Princess Diaries often become beloved teachers, school administrators, business owners, or experts in political science. In contrast, the grown-up girls once drawn to heroines like Anne Shirley, Sara Crewe, Jane Eyre, and others aren’t sure where to go. They don’t know how to shape their identities and often weren’t allowed to do so. A literary home built from their interests, but for the 21st century, becomes perfect for them.

“Disabled Book Girls?” Not Quite

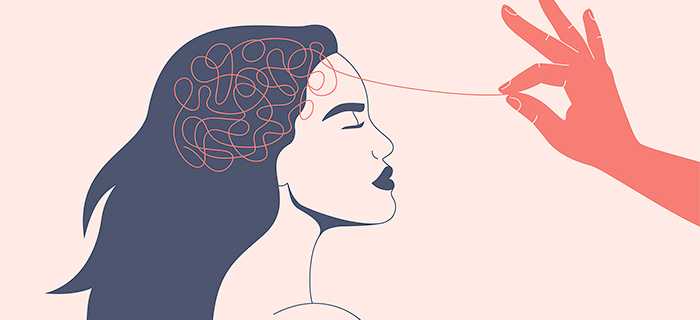

Liberating Neurodivergent Book Girls

The heroines of the books in our discussion all possess traits common in autistic females, as defined by diagnosed autistic females today and clinicians who are familiar with the autism spectrum. Sometimes, they possess traits common to other neurodiversity, such as certain types of Attention Deficit Disorder (ADD) or certain types of anxiety. Perhaps because of this, all these heroines’ books contain environments in which they must first survive unusual odds to thrive. That is, all fictional protagonists face hardships. For these heroines though, the odds and obstacles are often longer lasting, more traumatic, or connected to higher stakes than typical. Those parameters tend to play up a heroine’s coded neurodiverse (ND) traits, for good or ill.

If for ill, the heroine garners sympathy through victimization, or relatability because while her actions aren’t ideal, they are human. In either case, ND traits used for ill will force a young classic heroine to mature and grow. Conversely, if a heroine’s ND traits work for her or are viewed positively, she becomes more secure in her identity. She gains allies on her journey, and she’s able to tap into her strengths with the help of that support system. As she taps into those strengths, she can become “more neurodiverse,” which might put her more at odds with the people and environment around her. Yet becoming “more neurodiverse” can also help the heroine learn not only who she is, but what her purpose is inside a world not geared toward people like her, and where she belongs in it.

Be careful though, not to lock the heroines we discuss into neurodiversity as their only identities or distinctive traits. That is, these heroines can be coded ND, and we could use “ND girls” or “spectrum girls” to describe them the way we use “goth girls” to describe Goosebumps fans or “horse girls” to describe Saddle Club fans. But in the case of these “book girls,” such an identity would read more as an unfair label.

Neurodiversity, especially autism, encompasses disabilities with complex histories. It has been so misunderstood and maligned since its discovery, calling someone “autistic” or “ND” or “spectrum” just because they enjoy a coded heroine or book is minimizing and ableist in tone. It is more respectful to acknowledge the readers, the book girls themselves, as possible or probable spectrum-dwellers who found “coded” kindred spirits in fiction.

Simultaneously, we must liberate these book girls from any ableist connotations associated with autism, ADHD, or other neurodivergences. We must use a less clinical, less loaded name. We must speak of fictional heroines and real readers in accessible, empowering terms that communicate being this type of “girl” is about what a reader has, not what she lacks. It is about sisterhood and mutual enjoyment, not a social or behavioral deficit.

From here on then, we will call the real and fictional girls in our discussion “infinity girls.” This name originates from the infinity symbol, which the autistic and neurodiverse communities have adopted to show that everyone can fit into the wider world regardless of neurotype. It also originates from the symbol’s color, gold, which delineates our real and fictional heroines as “sparkling” in their stories, and contrary to how they are treated otherwise, “golden” or “the best” at who they are and what they are meant to do. Finally, the name “infinity girls” reflects these heroines’ “infinite” imaginations, perspicacity, creativity, exuberance, and other traits seen as unusual for their worlds.

What Makes an Infinity Girl?

Finally, we should set clear parameters for what makes an infinity girl. The easiest way to do this would be to say, “An infinity girl is coded ND,” and again, this is mostly true. However, just as every female (and male) presentation of neurodiversity is different, so is every presentation of an infinity girl. Therefore, while most traits will line up with what we know today as spectrum traits, some may not, or may point to both ND traits and the external situations in which these heroines find themselves.

In brief, a fictional heroine qualifies as an infinity girl if she displays atypical social, academic, or emotional behavior, but does so in ways today’s experts recognize as specific to females. Examples include but are not limited to:

-Deep and limited “special interests” still typical for most girls (e.g., books, fashion, dolls)

-An ability and desire to socialize, yet with older or younger friends, or with adults instead of peers

-Imaginary play beyond “typical” age/frequent, elaborate daydreaming, fantasizing, or overtalking/personifying or anthropomorphizing

-Defiance of authority (e.g., questioning, telling the truth at times deemed inappropriate), yet without conscious desire to aggress

-Under- or overreacting/reacting in ways considering inappropriate to a given situation/trouble with emotional regulation, but lacking physical aggression

Many other characteristics exist, as we will discover. However, these are the most common among our heroines. We will refer to our heroines as “ND coded” or having “infinity traits.” Recall that because neurodiversity was unknown during the eras of these heroines’ stories, none of them would have carried neurodivergence diagnoses. Nor are they meant to be read as “ND” through a 21st-century lens. Rather, our infinity girls are meant to be read as such because neurodiversity is a relatable commonality for 21st-century readers.

Anne Shirley, Anne of Green Gables

First published in 1908, Anne of Green Gables is not the first classic novel to boast an infinity girl heroine. It will be first in our discussion though, because its author, Lucy Maud (L.M.) Montgomery, is most famous for it, and because Green Gables spawned an entire series of nine books starring Anne Shirley. In the decades since Green Gables’ publication, readers’ love of Anne has birthed four films from Sullivan Entertainment, the sequel television series Road to Avonlea, and the three-season Netflix retelling Anne With an E. Anne Shirley then, is perhaps the most relatable infinity girl of all, the one who succeeds in “crossing over” and reaching the widest neurotypical audience. Still, she remains an infinity girl at her core, and the perfect one to lead the fictional group.

Divergent in Appearance and Behavior

Anne Shirley sets herself apart from the minute she comes to Avonlea. With her green eyes, pale, freckled skin, and “hair as red as carrots,” she can’t help being noticed. Today’s readers might know Anne’s phenotype only belongs to about 10% of the world’s population. Thus, Anne’s new peers and neighbors have likely never seen someone like her before. Worse, Avonlea is a small, insular town on the already isolated Canadian province Prince Edward Island (PEI). Anne’s adoration of fiction and extensive vocabulary, bordering on what we know as hyperlexia, already point to both ND coding and a level of education Avonlea residents probably aren’t used to from a preteen girl. Add that Anne is an orphan, with no real memory of or link to biological parents, and she becomes much more mysterious and suspicious.

However, Anne would still stick out in Avonlea if, as she says, “I were very beautiful and had nut-brown hair…and lovely starry violet eyes.” She would even stick out if she had living parents. Her dialogue gives away one reason why. Anne views the world with an idealistic and dramatic flair. She ascribes overblown adjectives to the most mundane things and places. For instance, when Matthew Cuthbert brings her home to Green Gables from the train station and shows her places like Barry’s Pond and The Avenue, Anne immediately re-christens them “The Lake of Shining Waters” and “White Way of Delight.” Anne is so enraptured at The Avenue’s cherry blossoms, she stands up in Matthew’s wagon and briefly puts the two of them, plus the horse, in danger. Yet she seems fearless when this occurs, pointing to a combination of both autistic and inattentive ADD tendencies.

Anne’s divergence continues as she adjusts to Green Gables and the expectations of Matthew and Marilla, who are not the foster father and mother she’s used to, but rather two aging, single siblings. Matthew finds her enchanting, a breath of fresh air in the monotony of increasingly hard farm life. But to Marilla, Anne is a conundrum, a burden who can’t help the way the boy she and Matthew needed could have. Anne “prattles on without stopping for breath,” “[sets her] heart too much on silly names,” and “is next door to a perfect heathen,” as the reluctant foster mom finds out when Anne reveals she’s never been expected to say her prayers and has never cared for God because He made her hair red on purpose. Marilla, with her down to earth personality and more stable history, doesn’t consider Anne is relating to new concepts the only way she knows how, through big emotions and bigger verbalizations related to her special interests, as happens when she says her first bedtime prayer aloud and sounds like she’s “addressing a business letter to the catalogue store.”

To a point, Anne “rolls with the punches” of her new life like a seasoned foster kid. Like a real infinity girl with autism, ADD, or both, she retreats into her books and daydreams as much as possible. Anne With an E shows her playing at being “Princess Cordelia” and monologuing on several occasions, lightening a mood often shadowed with traumatic memories. In addition, Anne constantly seeks connection with Matthew and Marilla, even when weaknesses like poor time management and her tendency to overtalk get in the way. For example, she asks to call Marilla “Aunt Marilla,” and begs to be called Cordelia in turn, thinking that although these aren’t their real names, the monikers will bring them closer.

Turned down on both counts, Anne is naturally disappointed. She’s let down again when Marilla fails to understand her attachment to her “window friend” Katie Morris. Yet this leads to a “hope spot” for Anne when Marilla takes Katie’s presence as a sign her foster daughter needs real girl friends. When it’s suggested Anne attend an upcoming Sunday school picnic, Anne immediately longs to go and meet her first “bosom friend.” Yet to earn this privilege, she must face a trial that will put all her ND traits, and thus the fullness of herself, through a “baptism by fire.”

Guilty Until Proven Innocent

Despite initial missteps, Anne wins enough of Marilla’s approval for the woman to give her a trial period at Green Gables. Marilla doesn’t specify the length or conditions of the trial, but Anne intuits she must use it to prove she can become what Matthew and particularly Marilla expect. She must mind how much she talks and about what; she must keep her frilly descriptors and desires to herself; she must not voice anything that would sound prideful, ungrateful, or ungodly, such as dissatisfaction with her hair and freckles. Anne doesn’t bottle her whole personality up. She emotionally and almost physically can’t. But a 21st-century reader might recognize in her a neurodivergent child trying, or indeed being forcibly trained, to suppress what neurotypical parents, teachers, or others in authority do not approve, in order to obtain tangible or long-term rewards.

For a short but crucial period, Anne succeeds. Yet when she fails, she fails miserably. One such failure revolves around Marilla’s treasured amethyst brooch. Anne has admired it before, so when it comes up missing, Marilla asks if she’s seen it. “I pinned it on yesterday, just to see what it looked like,” Anne confirms. Marilla jumps on the confession–“You had no business to meddle,” and presses harder. “Did you take it out and lose it?” Anne has done no such thing, but Marilla is so angry, so determined to believe otherwise, the girl can’t stand up for herself. Marilla declares Anne will stay in her room until she confesses to stealing the brooch, Sunday school picnic or no. Anne agrees because the truth is getting her nowhere, and a few days later, confesses she took the brooch, bent to look at her reflection in Barry’s Pond with it on, and let it slip into the water.

Marilla is ready to send Anne back to her former orphanage over her “crime.” Anne has stolen a valuable item, possibly an heirloom, and told yet another dramatic “story” to manipulate the situation. Anne With An E takes Anne’s plight further, having Marilla actually send her back alone, so Anne must retreat into overblown imaginings just to cope. In both cases, Matthew facilitates resolution, spotting the brooch clipped to Marilla’s church shawl in the original story, and going to fetch Anne in With An E after the jewelry is recovered. In both cases, Marilla is humbled because, when she fixates on Anne’s fabricated confession, she has to admit that as Anne says, “You wouldn’t believe the truth.”

Painful Yet Liberating Truth

Real-life infinity girls often find the brooch incident painful because they’ve been in Anne’s shoes, although the exact circumstances are usually different. A common neurodivergent trait revolves around speaking and acting in total honesty as much as possible. Contrary to stereotypes, this doesn’t mean neurodivergents (NDs) believe neurotypicals (NTs) are liars. It simply means NDs often bypass the subterfuge and social niceties NTs often use when getting to the “truth” of some story or incident.

Bypassing subterfuge is what Anne did, and coupled with her dramatic “confession,” it caught Marilla off guard, making Anne look ironically sneaky and dishonest. Real-life infinity girls often report similar experiences on social media, whether they’re confrontations over small “lies” to parents, or misunderstanding team-building games with complex rules at school or work, or getting in trouble because they were seen as backstabbing a coworker. Regardless of the specifics, they were guilty until proven innocent.

Still, infinity girls cheer for Anne at the conclusion of the brooch incident, because L.M. Montgomery lets honesty, and neurodivergence, win in equal measure after they lose. Marilla has to face the fact, she has a brilliantly honest child under her roof, and one who will obey her exact words–“You said you’d keep me in my room until I confessed, so I…thought up a good confession.” Marilla, who bases her righteousness on her religion, must acknowledge she’s probably righteous in that count, but Anne is the one who’s going to walk away forgiven in the brooch situation, in the eyes of a higher authority.

Conversely, Marilla, who is the “typically” well-behaved and accepted person, has to admit wrong and ask forgiveness–which Anne is open enough to grant. Anne was guilty based on personhood alone, which is a horrid injustice. But she reclaims a double portion of innocence because of who she is, and comes away stronger. In fact, it is this strength of character and reliance on absolute truth, frilly or not, that helps Matthew and Marilla grant her a place as a daughter of Green Gables.

Scarlet Emotions, Sensitive Heart

Throughout the rest of Anne of Green Gables, Anne’s ability, indeed her desire, to fit into Avonlea is often in doubt. Her future there is settled fairly quickly. Though Matthew and Marilla have the option to send Anne to work as a servant for Mrs. Blewett, a harsh woman with a brood of unruly children, the Cuthberts soon realize they don’t want that outcome for Anne or themselves. As Matthew notes, Anne “ought to have all the kindness we can give her,” and has brought too much joy, humor, and yes, usefulness as a physical and emotional help to Marilla, into their lives for them to let her leave. Plus, Anne With An E hints the physical and mental abuse Anne endured in orphanages and other foster homes has left her too traumatized for more loss.

Still, Anne continues “getting into scrapes” that cause both peers and adults to reject her in some form and make her look bad just because she is neurodivergent-coded. Many of these incidents come down to what Rachel Lynde calls “a temper to match her hair,” such as when Anne smashes her slate over Gilbert Blythe’s head for calling her Carrots, or when she responds to Rachel’s tirade against her looks and orphan status with “How would you like to be told you’re fat, and ugly, and a sour old gossip?”

Other incidents come from Anne’s tendency to let emotional fantasies, fueled by her literary daydreams, run away with her. This occurs once when she reenacts Tennyson’s “The Lady of Shalott” and ends up sinking John Barry’s boat, which she and her friends borrowed presumably without asking. The flaw pops up again when a mouse drowns in Anne’s attempt at plum pudding sauce because she used the cheese cloth as a veil while imagining herself as a nun. Refer back to our infinity trait of imaginary play at an unusual age and note that she is a high school and rising college student at both points.

But just as Anne’s brutal honesty and dramatic flair worked against her during her first days at Green Gables, her overall “scarlet” emotions match her hair and work in tandem with a highly sensitive heart.

Bosom Friends Lost and Regained

One of the best examples of Anne’s “scarlet sensitivity” lies in her friendship with Diana Barry. Like many infinity girls, Anne nurses this one close friendship throughout her book series and films. She has other girl friends and eventually, a romance with Gilbert Blythe, but Diana is her first, deepest, and most loyal companion. Anne calls her a “bosom friend,” meaning “best friend” but connoting a much deeper bond. TV Tropes calls theirs a “Romantic Two-Girl Friendship,” in reference to the Japanese custom of a “Class S” friendship between two adolescent females, meant to prepare them for, and give them acceptable intimacy other than, marriage. The original Green Gables novel contains a scene where Anne sobs brokenly to Marilla over the very idea of Diana getting married and “leaving” her.

In other words, Anne and Diana are extremely close in every way other than sexual. They hug, hold hands, and might kiss on the cheek as was more common in the 19th century, but are chaste in all intentions. Especially for introverted and socially starved Anne, Diana is her ideal sister-friend, someone who finally understands and loves her the way no other peer ever has. Therefore, Anne gives Diana 100% emotional intimacy even if, as in Anne With an E, the other girl begins as a bystander to classmates’ bullying. Anne sometimes engages in fantasies of rescuing Diana from danger, such as nursing her through smallpox, subsequently dying so Diana can water a rosebush planted beside Anne’s grave with her tears.

Fortunately for Anne, Diana is strong enough to disengage with bullies, but enough of a “follower” to participate in her adventures, fantasies, and wild stories, such as of a haunted forest. Diana finds them amusing and a great escape from her more typical, ladylike life. But when Anne mistakes currant wine for raspberry cordial at the girls’ first “adult” tea, their idyllic friendship shatters.

Mourning and Maturing

Diana drinks three tumblerfuls of wine, and the ever-proper Mrs. Barry blames Anne, the orphan of unknown origin with an already questionable behavioral record. “Diana will never see you again,” she decrees. An incensed Marilla stands up for Anne, explaining her daughter made an innocent mistake and anyway, her currant wine isn’t meant to be drunk in such great quantities. If anything, Diana should be [“sobered up] with a darn good spanking!” Minister’s wife Mrs. Allen attempts to reason with Mrs. Barry as well, and arranges a secret meeting between the devastated girls. But Mrs. Barry won’t budge, and Anne remains heartbroken for the rest of the summer.

Anne continues struggling when school resumes, showing us another infinity trait. Diana resumes socializing, but the next time we see Anne, she’s alone in the schoolyard. Moreover, she looks crushed because Diana and other friends appear to be laughing at her. Indeed, if they lose their deep friendships, real-life infinity girls tend to lose any social moorings. They may also fear negative behavior they see in peers’ circles is directed at them, or that normal peer behavior is secretly negative. Anne never comes out and says anything, or does anything that reveals she feels thusly. But she does retreat into a social shell, until she meets new teacher Muriel Stacy.

As Anne’s instructor, Miss Stacy can’t provide the type or level of friendship Anne needs from a peer. As infinity girls do though, Anne attaches herself to the teacher in as deep a way she did to Diana, if differently. These two are mentor-mentee, not “Class S” partners. But Anne immediately identifies with Miss Stacy’s intelligence and zest for life. She hungers for her teacher’s praise and when she displeases her, corrects the misstep as soon as possible. Miss Stacy, for her part, is able to nurture Anne’s imagination and sensitivity in a way no other adult has bothered to before. She’s able to help Anne learn balance between the escapism of fantasy and the need for reality. That balance helps Anne self-regulate her “scarlet” moments so that when they happen, she feels more controlled. Over time, she’s able to “channel” them as they happen and put them to good use.

Anne does not “regulate” herself out of her deep emotions completely. To do so would be a high, harmful level of neurodivergent “masking” that would probably cost her what social ground she has gained. Yet as Anne takes the more dutiful and mature path more often–eschewing fiction when she has a geometry assignment or spending more time learning life skills from Marilla–she does show she can meet neurotypicals halfway when needed. In turn, she deepens her mentee relationship with Miss Stacy, puts aside some of her rivalry with Gilbert Blythe, and garners new friendships with girls like Ruby Gillis and Jane Andrews. These friendships are warm, but more casual than what Anne experienced with Diana. Still, they set her up for success when she needs more permanent community support as a young adult.

Rebuilding from Literal Ashes

Anne is best known for her love of books and writing; readers and viewers see her devouring books and writing novels, poetry, and nonfiction throughout her adventures. But one deep interest, or “special interest” in today’s ND terminology, that Anne’s media series explore is her acumen with medicine and lifesaving. The original Anne films and Anne With an E give this infinity heroine unique opportunities to use skills developed from these interests. Both incidents let Anne carve a permanent niche in Avonlea.

The Anne With an E incident is placed earlier in Anne’s story timeline, before Diana’s brush with currant wine and before Anne meets Miss Stacy. However, for those who accept both the Netflix series and the Sullivan films as possible canon, it is one of Anne’s “most golden” infinity moments, and it is used in her favor when she’s maligned for intoxicating Diana. In this timeline, Anne is still new to Avonlea, her future at Green Gables is shaky, and she has no school friends yet. But when classmate Ruby Gillis’ home begins to burn and the whole town shows up to contain the blaze, it’s Anne who jumps into action. “Close the windows!” she cries when the adults try to keep them open. “Fire feeds on oxygen!” She runs headlong into the house, slamming all openings closed.

Anne’s right, and her observation, plus other quick thinking, saves Ruby and her family. Matthew, Marilla, and astounded neighbors ask Anne how she knew what to do; Anne explains in her orphanage, she had nothing to read except a fire safety manual. Starved for material and knowledge, she read it over and over, and committed the information to memory. On the surface, this is a classic “neurodivergent” thing to do; many ND individuals will read the same books or watch the same media to the point of memorization for comfort, or from anxiety or boredom.

Remember though, Anne doesn’t devour education for its own sake. To gravitate to fire safety, she already needed some level of interest, or at least sensitivity that made her care for fellow orphans’ lives, even if she had no sympathy for her abusers. When it came to the Gillises, Anne probably reacted from a mix of a post-traumatic trigger, concern for unknown people who might still become allies, and the thought, “I know what to do here. If I do it, maybe these people will accept me.” Again, she’s proven right. Her heroism wins back the Barry family’s favor when she needs it, and secures her a place in the community.

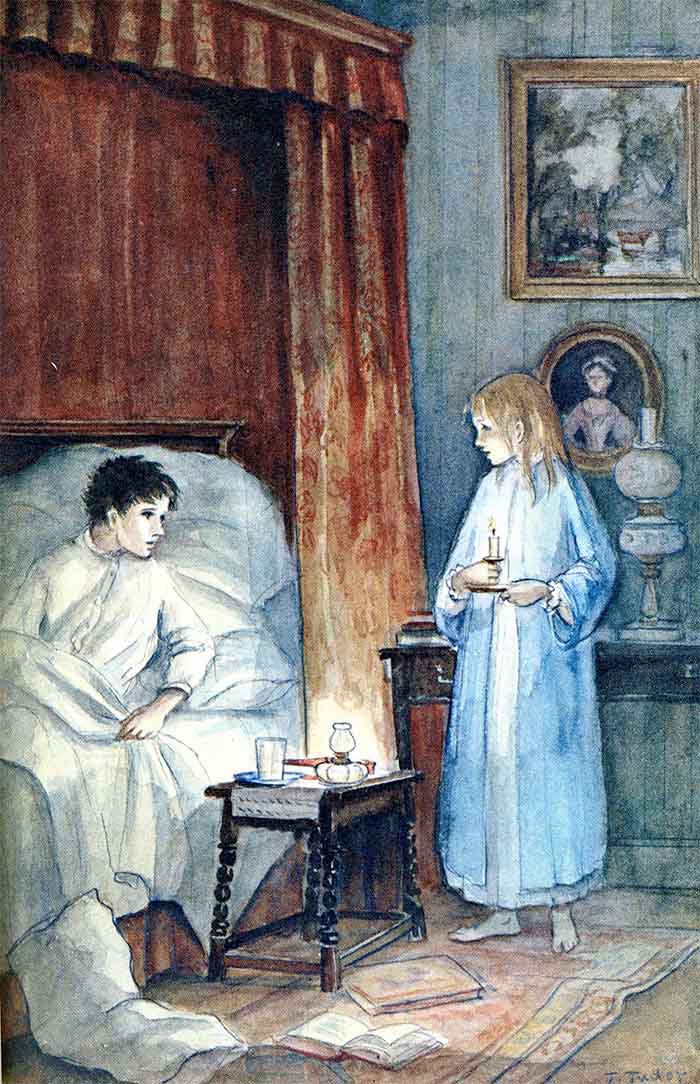

Trauma Redeemed, A Child Saved

The Sullivan Entertainment film Anne of Green Gables ties Anne’s medical acumen and cementing into Avonlea more closely to the regaining of Diana’s friendship. In fact, it becomes one of the defining moments of her early teens, if not the moment that marks her beginning of young womanhood. A few months after establishing a mentorship under Miss Stacy, Anne has earned the privilege of being in “the Queens class,” after-school instruction for older students who are eligible to attend college in Charlottetown. Her studies, and her determination to best Gilbert Blythe academically, take Anne’s mind from her broken fellowship with Diana. But shortly before Christmas break, Anne finds her distraught best friend crying on her doorstep.

Diana’s preschool-age sister Minnie May is sick with croup, and the girls’ parents are out of town at the same political rally Marilla and most of Avonlea, including the local doctor, are attending. In 19th century PEI, croup is a serious respiratory illness, known to kill without quick, consistent treatment. Matthew’s home, but he must take the family’s own carriage and track down a doctor. Anne, the closest thing to a levelheaded adult in this scenario, is hit with some “scarlet” realities. Helping Diana now means risking further shunning. Worse, Minnie-May’s condition is triggering. Anne has been forced to nurse abusive foster parents’ biological kids through croup before, with no regard for her own health. She knows what will work, but if she gets the treatment wrong, Minnie-May could die, and that could ruin Anne’s life in myriad ways. For once, an overreaction or retreat into a dramatic story would be neither out of place nor unforgivable.

Instead, Anne makes the most honest, black-and-white, and truest to self decision she can. The strongest truths rise to the top of her brain: Diana is still her kindred spirit, and if Anne doesn’t act now, an innocent will die. No matter what other wrongs have been done, that is wrong no matter what. Resolved, Anne grabs some ipecac–after double-checking the label, having learned from the cordial vs. wine mix-up–and hoofs it to the Barrys’ place. She takes charge of the situation with an “infinity” signature, using truthful sarcasm with an inept babysitter and barking orders without regard for social niceties.

By the time a doctor arrives, Minnie-May’s lungs are clear. “Would’ve been too late by the time I got here,” the doctor observes. “You saved this little baby’s life.” And indeed, while Mrs. Barry reads as empty-headed for only accepting Anne after that fact, everyone else simply offers the praise she was due. Anne did not become a neurodivergent, life-saving “inspiration.” She took advantage of the chances to use the gifts she always possessed. She became the best person to bring new ways of thinking to Avonlea and real-life book girls.

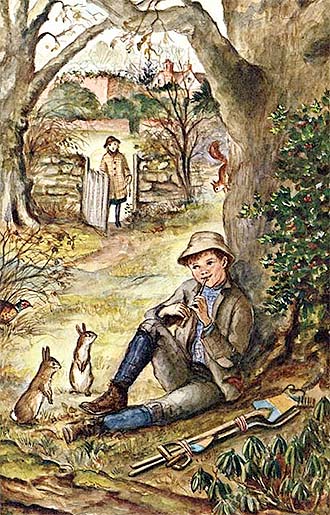

Mary Lennox, The Secret Garden

In 1911, Great Britain would give book girls another infinity girl with whom to identify, Mary Lennox from Frances Hogsdon Burnett’s The Secret Garden. Again, Mary Lennox is not the first infinity girl in classic literature’s Western canon. She’s not the first British one, as we’ll see later. As with L.M. Montgomery though, Burnett is most famous for Mary and The Secret Garden.

Like Anne of Green Gables, The Secret Garden has never been out of print. It has achieved equal or greater fame, spawning not only three feature films (1949, 1993, and 2020), but a 1975 BBC miniseries sometimes packaged as a film, a Broadway musical, an anime series, and a modern graphic novel retelling, The Secret Garden on 81st Street by Ivy Noelle Weir and Amber Padilla. The popularity of Mary’s story can’t be denied or escaped. Yet, add in her kinship with infinity girls, which has only been explored in recent decades, and her character becomes more fascinating than her story. It begs for someone to take some literary gardening tools and “dig deeper” into why so many readers still gravitate toward her.

The Rose Has (Useful) Thorns

At first blush, Mary Lennox is the kind of person an infinity girl doesn’t want to identify with. She’s the stereotype of an ND person, the type doctors and other clinicians point to as a reason to malign neurodivergents and autistics in particular. Frances H. Burnett describes Mary as “the most disagreeable girl anybody had ever met,” “always ill in one way or another,” “sallow,” and “imperious.” Mary is used to getting her own way all the time, not shy about saying so, and prone to verbal abuse if denied anything. It’s somewhat understandable given that she’s a British child growing up in colonized India. Yet the way she calls native-born household staff “pigs” and “daughter of pigs,” knowing this is a grave insult in their culture, and slaps them around, is abysmal behavior.

Burnett reveals Mary is emotionally stunted, ND-coded or not. Cognitively and physically though, she’s typical if not advanced. In the beginning then, reading her as ND wouldn’t net her any sympathy or empathy. Mary might instead be blacklisted as a neurodivergent who “knows better” on some level, but makes the population, real or fictional, look bad. To a real infinity girl, she might read as someone on whom clinicians might use certain forceful, abusive therapies.

Real girls might shun Mary because she reminded them of their traumas and represent the reason ND kids and adults continue experiencing abuse. Failing that, real infinity girls might shun Mary because they feel superior to her. They either don’t express their emotions in “abnormal” ways like Mary does, or they’ve been taught not to, often because they went undiagnosed or got forceful treatment along with a diagnosis, even if that treatment wasn’t classically abusive. Thus, Mary Lennox is the “more coded” or “more disordered” person these girls can’t identify with, lest they risk rejection or punishment.

Yet even the infinity girl readers who shun Mary Lennox can find a “kindred spirit” in her. Tenacity, a strong sense of justice, and a unique brand of “street smarts” exist inside her thorny exterior, not in spite of it. She’s gorgeously, unapologetically an infinity girl, but not in all the soft, winsome ways of Anne Shirley. Mary Lennox unites some of Anne’s infinity traits–creativity, mature intelligence, and a kind of sensitivity–with the neurodivergent traits parents, teachers, peers, and clinicians often find more “difficult.” She displays what today’s disability experts call “problem behavior” before or instead of the compliance, quiet, and social innocence those experts expect of today’s ND girls. Yet it is Mary’s “thorns” that make her stand out, turn her into a heroine, and draw real infinity girls toward her.

Melting Down and Standing Up

The more time readers and viewers spend with Mary, the thornier she acts. Neurodivergence and disability experts would likely brand her with labels like “uncooperative” or “noncompliant,” and those around her would likely agree. After Mary’s largely absent parents die of cholera (casualties of an earthquake in one film), she’s sent back to England from India to live at her uncle’s mysterious Misselthwaite Manor. In the interim, she’s sullen and uncommunicative with the children she meets, unresponsive to both their friendly overtures and their teasing. In one adaptation, she pulls back from a chaperone’s well meant pat on the shoulder, looking ready to spit in his face.

Upon meeting Misselthwaite housekeeper Mrs. Medlock, Mary maintains a flat, snappish tone when answering her questions. She combines said tone with biting honesty–“My mother didn’t have time to tell me stories,” “[My father] was always ill…he didn’t care about me.” She responds to offers of food with a surly, “I’m not hungry” and demands help undressing from her traveling clothes. When Mrs. Medlock voices a child of nine should be able to dress and undress independently and asks if children in India get carried around in baskets, Mary barks, “How dare you talk to me with such disrespect?”

Many young readers meeting Mary for the first time would observe her behavior and think she’s being a spoiled brat. After all, Burnett has described her in everything but those words. Even this writer, who herself has cerebral palsy and still needed some help with the finer points of dressing at Mary’s age, was flabbergasted at how she dare act around adults. Any identification the two of us might’ve had at that point disappeared quickly. Slightly older and more sympathetic readers might still notice Mary tends to phrase her dialogue in terms of “me,” “how dare you not defer to me,” and other self-driven cadences.

An adult reader looking back at Mary though, an infinity girl in particular, will see something different in her behavior. Mary is, yes, a child raised in a self-centered environment. Yes, she doesn’t have a concept of deference to adults. At the same time, the adults around her such as Mrs. Medlock are being unreasonable to expect anything else. Mary was raised by servants, not parents. She was cared for physically, but never educated or nurtured from an emotional, moral standpoint. She never had other children to interact with; she has no reason to know or expect that negative behavior earns ostracism. She can’t be held responsible for performing life skills she’s never been taught. Yet when she expresses frustration at any of this, Mary gets scolded and shamed for the way in which she expresses herself. It’s never considered that Mary might be having an ND-coded meltdown. This is forgivable in an era where meltdowns weren’t known or named, but through a 21st-century lens, the cues and less than ideal responses are easy to spot.

Most importantly, Mary is a grieving child for whom the entire world has changed at a breakneck pace. She doesn’t grieve the way kids in her era are expected to. In the 1993 adaptation, it’s noted several times, “She never cried when her parents died.” Mary herself tells us she doesn’t know how to cry. But her grief becomes the overarching umbrella for her infinity girl coding and heroic arc. That is, Mary never has one big meltdown or breakdown the way contemporary ND characters sometimes do. But she does scream out at her servant Martha when the latter makes assumptions about Indian culture–“You don’t know anything…none of you, nothing!” and collapses into a sobbing fit. She bursts into tears in the miniseries at the frustration of being the lone kid in a house full of adults too busy to play, and lashes out privately when Medlock refuses to let her out of her room or tell her who’s crying down the hallway.

Every time Mary melts, infinity girls can empathize, no matter what caliber of meltdown they’ve had or experiences they’ve attached to them. More importantly, they can find a blossom beginning to grow on the stalk of Mary’s infinity “plant.” Mary has always struggled with imperiousness and impatience, but at as she settles into Misselthwaite, we recognize those weaknesses have reasons. They’re birthed from a spoiled, neglected, brilliant kid who’s never been treated as a person. Now, within a new environment, Mary has the chance to reshape herself with help. She’s melted down a lot and shown the worst of herself, but in doing so, she’s let herself become vulnerable. In many ways, melting down has prepared her to stand up for herself and others.

Blooming Under Correct Care

Mary becomes less imperious as The Secret Garden progresses, but never loses her “edgy infinity girl” persona. Those edges make her the perfect fit for Misselthwaite just as Anne was the perfect fit for Avonlea. To wit, Misselthwaite is a mysterious, “closed circle” setting. All the book’s action takes place within the manor or on the grounds, and any unanswered questions revolve around the house’s secrets, as if the building itself were a character. In many ways, The Secret Garden almost reads like Gothic horror for kids. Therefore, it needs a young heroine who remains likeable but tends away from sweetness and light. That heroine needs to grow and flourish, but cannot become a model child of her era once she reaches “full bloom.” Like all infinity girls, Mary Lennox needs and finds a social circle, but it’s an intimate and atypical one that works for her.

Real-life infinity girls often turn to older children or adults as friends, and Mary is no exception. True, Misselthwaite’s population is mostly adult. Yet Mary’s acerbic take on life and being left to her own devices for her first decade or so, already predispose her to seeking grown-up company, as long as those grown-ups feel safe. For instance, once Martha shows she’s willing to show Mary grace and patience, the younger girl relates to her more as an equal and confidante. The two speak amicably about Martha’s life on the moors with eleven siblings and a loving single mom. Martha brings Mary a gift of a skipping rope taken from her own wages. Mary accepts with confusion but gratefulness, and lets Martha teach her the use of the toy. Similarly, Mary develops a friendship with footman John in the BBC miniseries. Said footman treats his young charge like an adopted sibling from a foreign country. He uses reverse psychology to teach her basic politeness, risks breaking rules to play a noisy card game when she needs cheering up, and is ready to dive into the manor pond when Mary goes missing and might be in danger.

Later, Mary develops what TV Tropes calls an Intergenerational Friendship with Ben Weatherstaff. Ben is the oldest and longest-serving gardener on Misselthwaite’s staff. As for Mary, her principal interest is in flora and fauna. Her first few meetings with Ben involve her asking him to identify strange English flowers for her, or to explain how he became close with a particular garden robin. Though unsociable himself, Ben obliges. In fact, it’s his unwitting brand of “reverse psychology”–walking away when he’s done conversing, refusing to capitulate to Mary as that era’s servants “should”–that gets her to relate to him more like a typically polite kid.

Mary remains neurodivergent in their interactions. For example, she relates better to Ben’s plants and robin than the man himself at times, because he is still an adult whose authority makes little sense. And when Ben dishes out hard truth–e.g., it’s not hard to believe Mary’s never had any friends–she dishes it right back. For example, Ben shouldn’t believe everything he perceives or hears about others, like her cousin Colin being a “poor cripple” with “crooked legs.”

Mary then, gets to “bloom” just as the garden in her story does. Like real-life infinity girls though, she can only bloom under the right “gardeners'” care. Interestingly, it’s not her Uncle Archibald or Mrs. Medlock, the assumed “proper” guardians, she turns to. These two mean well, depending on the story version you’re consuming. But Archibald is away more than home, and still enmeshed in grief over the death of his wife and the weakened, ill state of his only son. As for Medlock, she’s a housekeeper, a high-ranking servant with an entire house and staff to look after. Moreover, she’s become what TV Tropes calls a “Well-Intentioned Extremist.” She’s so determined to keep Colin well, watch over Misselthwaite, and keep her job, she sees Mary, a prepubescent orphan who’s largely raised herself, as a threat rather than a child in need. Real infinity girls might see in Archibald and Medlock the well-meaning “experts” who tried to help, but suppressed, shamed, or worst-case scenario, abused them. Conversely, they might see in Martha, John, or Ben the people who provided support, kinship, or comfort, although they weren’t experts in neurodivergence.

Unlocking Doors, Breaking Barriers

Infinity girls are often seen as unusually compliant. They are rule-followers, organizers, and though they prefer working alone, will be team players if the situation demands it. Infinity girls may get vocally upset if someone intentionally breaks rules. Their male counterparts can experience this, too, but with infinity girls, it usually goes unnoticed because “infinity guys” are more likely to come across as aggressive. They’re also more likely to be excused for aggression or vocal dissatisfaction, whereas girls are not, even in a society striving for a more egalitarian mindset.

Mary Lennox fits this trait, but she’s an unusual encouragement to real infinity girls. From page one of The Secret Garden, she’s surrounded with people and situations that break the rules, literally and figuratively. Her parents break the rules of good parenting with their neglect. They then break the ultimate rule by dying and leaving her with no one except an uncle she doesn’t know and who also breaks guardianship rules because he’s another absentee. The English servants she meets break the rules she knows govern servants because she orders them to do things for her–and they outright refuse, using adult or late teen status as justification. But Mary doesn’t understand this because adult status has never mattered before, nor is she given any context for why it suddenly does.

When Mary meets her cousin Colin, she discovers he’s allowed to break the rules that govern her because he’s sick and disabled–but despite the evidence of this she can see, it doesn’t add up when she compares Colin’s strong, if sour, spirit to whatever meek stereotype of disability she’s absorbed. Nor does it square with the adults’ obsequious attitudes. Real-life infinity girls find themselves nodding along with Mary’s mounting frustration. They might say, “No wonder she’s yelling and smart-mouthing these people. They’re being totally unfair!”

But Mary’s not just an encouragement because she lives the reality of a rule-breaking world. Unlike so many infinity girls who’ve been taught, “trained,” or outright abused into compliance, Mary gets to break rules right back. Our heroine quickly learns that in the world of Misselthwaite, one in which nothing is as it seems and no one will tell her the whole story, she has no other choice. Her thorns stand her in good stead again, because as she rejects Misselthwaite’s conventions, Mary carves a niche in her new house and her new world. Like a flower pushing up through concrete she declares, “No. The environment may be hostile, but I’m going to grow. I didn’t choose to be here, but this is my home now, and I will make sure I belong.” Every time she pushes, she lets her real readers or viewers know they can, too.

The Secret Garden: Physical Barrier, Physical Space

Mary’s first few days or weeks at Misselthwaite don’t look too promising. She’s already clashed with Mrs. Medlock, and while she gets Martha to help her with tasks like dressing, she’s basically shooed away to play by herself every day without supervision. She barely eats and has no education or socialization, yet gets in trouble if she goes looking for a book to read or something to do in the house in general. Yet Mary does latch onto a few new things and experiences, like the aforementioned robin and new flora, such as snowdrops and crocuses. And when Martha lets slip that the manor has a locked garden, Mary fixates on the story like a modern neurodivergent girl with a cool new interest. She perks up, full of questions. Where is this garden? When and why was it locked? Has anyone been inside?

Mary gets some help adjusting to her new environment, such as when Martha brings her the skipping rope, or when Martha’s brother Dickon sends her a package of children’s gardening tools. Yet the secret garden itself remains Mary’s primary focus, even as she subconsciously opens up to Martha, Dickon, Ben, and others. The implication is, Mary finds social connection difficult, partly because of grief, partly because of neurodivergence, and largely because social interactions have never been positive. But she tends to succeed when alone or with animals (an early scene in the book shows her making brief friends with a snake in her parents’ dining room). So in seeking the garden, Mary is doing what many ND people do in real life, seeking a physical space where they can be themselves without judgment. When she unearths the key to the garden, then, it’s a moment of triumph on two counts. She breaks a longtime barrier of Misselthwaite, part of the “spell” she tells us in narration hangs over the house in the 1993 film. More importantly, she unlocks a success to a physical avenue toward emotional success, accomplishment, and healing.

The moment Mary unlocks the garden door is one of the most touching in her story. “I am standing inside the secret garden,” she whispers, hardly daring to disturb the decade-long, almost sacred silence. The 1975 miniseries accompanies this with a gentle, almost haunting oboe melody as Mary explores her new domain and muses about being “the first person that has spoken in here for ten years.” She revels in the stillness, and as she notices evidence of living plants, her latent nurturing instincts toward flora take over. She begins clearing weeds and detritus, becoming so involved in the task she loses all track of time, and talking soothingly to the little shoots. “I’ll let you all breathe, I promise,” she comforts them. In her voice, it’s easy to hear the little girl who never got comforting words from her parents and gave up on receiving such gentleness, but wants to give it another chance. Perhaps that desire, along with natural ND coding, drives her to pursue gardening despite the fact that doing so means admitting ignorance, a circumstance she wouldn’t have tolerated before.

Dickon Sowerby: Social Barrier, New Social Headway

Mary opens herself to this risk with Martha’s younger brother Dickon Sowerby, and she’s rewarded. A couple years older than her, Dickon is still whimsical, and rather like Mary, a rule-breaker. He’s more comfortable with his cadre of animals, some of them formerly wild, than people; in fact, the 1993 version has him meet Mary because his pet crow Soot escapes in the manor’s garden paths. Dickon also doesn’t let Mary’s higher class, or prickly emotional armor, deter him. Actually, neither child “sees” class. They relate almost as guarded, but friendly fauna. Mary is the colorful new bird with an injured wing. Dickon is the garden native and expert who looks plainer but fascinates his new friend and is eager to show her she’s safe.

Dickon agrees to keep Mary’s secret of the “stolen” garden, and the two go to work restoring it together. At first, they bond because they don’t have to socialize. Over time though, Mary finds it easy to talk with Dickon, and vice versa. Any distinctions or prejudices they might still have lie forgotten in the soil, and Mary maintains the first true peer friendship she’s ever had. The fact that it’s an ND-coded friendship, written in an era before the spectrum was known, is a bonus for infinity girls. The fact that Mary was able to form this friendship while allowing someone into her sacred physical space, can also give real infinity girls encouragement that this is possible when the person and time are right.

Colin and Archibald: Emotional Barriers, Emotional Safety

As with the garden, Mary has been confronted with mysterious crying in the manor’s corridors since her arrival. As with the garden, the adults have ignored her questions or put her off. In this case, they’ve outright lied. Martha once blamed the crying on a young maid’s toothache; the 1993 film shows Medlock blaming the household dogs and dragging Mary back to her bedroom, threatening to box her ears, when the girl tries to investigate. Most commonly, Mary is told she’s hearing the English moor’s wild nighttime winds, which sometimes sound like a wailing person. Mary never buys the excuses, although it is a particularly rainy, windy night when insomnia drives her to investigate again.

This time, with no one else awake to catch her, Mary tracks the crying all the way to its source, her cousin Colin. Colin is her age, but much paler and thinner even than she was on arrival to Misselthwaite. When Mary asks why he was crying, Colin explains he was in pain and ill. “I’ve spent my whole life in this bed,” he tells her in the 1993 film, adding, “I’m going to die.” Mary asks what his diagnosis is, but Colin just shrugs. “Everything,” he says. “If I live, I may be a hunchback.” He goes on to say he can’t walk, has never been outside, and can’t bear for people to see or talk about him. He must also receive anything he asks for, and no one in the house dares upset him. Any stress could send Colin spiraling into fatal illness, and since he is the heir, that’s unacceptable. He is master in the absence of his father, so everyone has no choice but to abide by his wishes.

Mary accepts Colin’s reality to a point. She visits Colin regularly, sharing stories with him about what it’s like in the gardens and enjoying his massive collection of books and playthings. The 1993 film shows the cousins playing with a puzzle and puppet show together, while the original book and miniseries show them exclaiming over a parcel Mary’s uncle sent her, which contains a book about gardening, a silver pen, and a monogrammed writing case. Mary doesn’t tell Colin she’s unlocked the secret garden, but lets him believe that no one knows about it except the two of them. Using stories of the potentially magic locale, she helps Colin believe–again, to a point–that his future might hold something other than the illness and early death everyone from the household servants to his doctor to his personal nurse have predicted.

But as brilliant and tough as she is, Mary is still a little girl. Breaking her own emotional barriers has been hard enough, and Colin’s are taller and thornier than she can handle. One night, she finds Colin in the throes of one of his frequent temper tantrums, screaming and wailing because of back pain and phantom sensations of lumps. Mary loses her own temper, good and sick of having Colin act like a “rajah with emeralds and diamonds…stuck all over” around her and everyone else. “I wish everybody would…let you scream yourself to death!” she exclaims, going on to inform Colin he doesn’t have a “single lump” on his back. “It’s just hysterics and temper,” our heroine “diagnoses,” making it clear she won’t coddle her cousin.

Shocked out of hysterics, Colin calms down. He begins to accept, as he admits when the cousins are alone, “Maybe I’m not ill.” Mary confirms she’s never seen signs of actual sickness in Colin, only understandable weakness. She coaxes Colin to sleep with tales of the secret garden and a plan to take him there in his wheelchair with Dickon’s help. In making this plan to help Colin, our heroine will find she has taken her barrier-breaking as far as she can by herself.

The Flowering of Acceptance

Releasing the “pressure valve” on her bottled frustration, especially with other people who’ve been allowed to do whatever they like, has set Mary up to do her next heroic act, breaking Misselthwaite’s largest and strongest emotional barrier. Yet just as real infinity girls need the right support, often from older kids and adults, to succeed, so does Mary. She gets Colin to the garden successfully, and she, Colin, and Dickon enjoy several idyllic afternoons there, glorying in multicolored flowers and the companionship of Dickon’s pets. Some adaptations show us moments like Colin feeding a baby lamb, Mary and Dickon sitting on a swing while Colin takes a picture, or Mary and Dickon racing Colin down a path in the latter’s wheelchair. In all adaptations, Colin’s character arc culminates in his walking again.

For Mary though, resolution isn’t as easy as the TV Trope “Throwing Off the Disability” (which, though accepted in Burnett’s day, carries unfortunate implications). In the 1993 film especially, infinity girls see that Mary could get Colin to the safety and “healing” of the garden. She could get him to admit he accepted the narrative of illness and death because of his youth, naivete, fear, and parental neglect. She could nurture the garden and symbolically nurture herself, taking part in her own healing. What Mary couldn’t do, still cannot do, is heal herself completely. Like a real infinity girl, she needs authentic acceptance, not only from her home, friends, and a space she calls hers. She needs love and wanting at a depth she hasn’t yet experienced.

Since Mary is ten and living in an era well before solid foster families were common or “families of choice” routinely accepted, she almost must have this need met through a biological guardian. Unfortunately, her Uncle Archibald remains emotionally unavailable up to the end of The Secret Garden. He is neither abusive nor cold. Most adaptations paint him as intrigued with his niece, who reminds him of his late wife. Archibald also understands Mary is “just a child” and means no harm to his home or son, as he sternly tells Medlock in the 1993 film. He recognizes her concrete needs, such as clothing, food, education, books, and toys. But until story’s end, he’s oblivious to Mary’s emotional needs and struggles. It takes seeing how well she’s tended his garden, and what that symbolizes, to wake Archibald up to what, and whom, he’s missed in the decade since his wife’s death.

The original book and most adaptations touch on this in fairly detached ways, as the main characters are seen bonding in the garden one last time, with most of the focus on a healthy, abled Colin. The 1993 film, though, puts the focus on Mary and her uncle. When she rushes off by herself to the garden stream crying, “No one wants me,” Uncle Archibald follows her, coaxing softly, “What is it? Why are you crying?” When Mary expresses grief for the garden and Colin in angry tears–“It wasn’t wanted…you never wanted to see,” consumers know she’s really talking about her heart, though she doesn’t know and can’t articulate those deep emotions. Archibald does know though, and comforts her. “Don’t be afraid. I won’t shut it up again,” he promises, speaking of both the garden and his neglected heart and spirit. The two share a hug, and Mary notes through narration that this is the moment her uncle learned to laugh, while she learned to cry. The implications are, Archibald will stick around for his niece and son, and life at Misselthwaite will become healthier and brighter. Mary will have a home where she’s given proper support, and she’ll grow up like a child her age should, but into the unique girl she was always supposed to become.

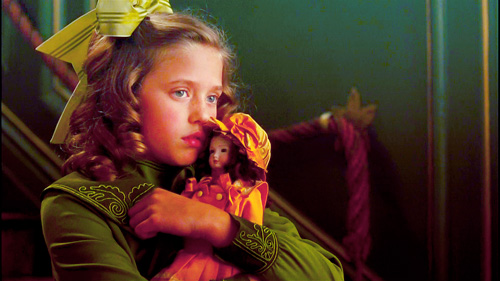

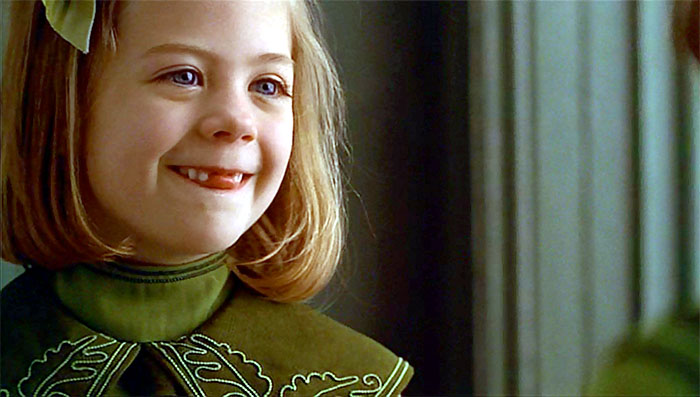

Sara Crewe, A Little Princess

Frances H. Burnett gave readers and viewers another infinity girl in her lifetime, Sara Crewe of A Little Princess. Sara’s story was published before Mary’s, as a novel in 1905 and as a serialized story a few years prior. Yet Sara’s placement after Mary in our discussion is intentional, because she is the lesser-known of Burnett’s heroines, and a controversial addition to our lineup. Sara is the star of a novel, but A Little Princess is probably better known because of its three film versions–a 1939 Shirley Temple film, a 1986 BBC/Wonderworks miniseries collaboration, and a 1995 film starring Liesl Matthews, who was unknown at the time and only went on to act in one more movie.

Furthermore, Sara doesn’t read as an infinity girl the same way Mary Lennox or Anne Shirley do. She exhibits some key infinity traits, such as atypical socialization, engagement in imaginary play beyond the typical age, and unusual interests. Yet Sara’s manifestations are different from Anne’s or Mary’s, markedly so. She also begins her story at a significantly younger age than the other two. At seven, she’s three years younger than Mary and five younger than Anne. At that age, she’s expected to leave her one living parent and constant adult presence for boarding school, so her ensuing reliance on fantasy seems more natural than neurodivergent.

But on close analysis, Sara Crewe more than earns the “infinity girl” title. Her characterization may seem typical for a displaced if mature child, but her ND traits push themselves forward in ways tailored for Sara’s personality alone. More importantly, her external circumstances are the longest and most difficult we have seen yet. They take up the bulk of “real time” in Sara’s story rather than influencing it from off-page or offscreen. Sara, then, is not only an infinity girl. She is the infinity girl real ones can draw courage from when their core selves are threatened.

A Princess in Exile

Like Mary Lennox, Sara Crewe spends her childhood in colonized India. She’s the child of widower Captain Ralph Crewe, who dotes on her when at home. Still, Captain Crewe’s military duties take him away more often than either father or daughter like, and Sara is usually left in the care of household staff. Therefore, Captain Crewe makes the most of the time he can spend with Sara, and she does become spoiled.

Unlike Mary Lennox, Sara is the TV Trope “Spoiled Sweet.” She has every possible material blessing, from expensive toys to a full-size, authentic stuffed tiger, from piles of books she reads and enjoys to luxurious clothing in vibrant colors. At the same time, Sara adores her father and other caregivers. She relates to servants as grown-up friends and enjoys learning everything about India from the Hindi language to the names and functions of different Hindu deities. If Sara makes observations modern readers would consider prejudiced, they are totally innocent on her part. If she relates to servants as “lower” than herself in any way, it is always with respect, and only because she lives in an environment where they are expected to meet her needs. She embodies the trope “Nice to the Waiter.”

Sara is physically and emotionally generous, immediately grateful for everything she is given, and hungry for intangibles like time with her dad more than new possessions. In fact, Sara never outright asks Papa or any other adult for anything tangible. If she gets a possession like her new doll Emily, it’s because the purchase was a mutual idea between Papa and her. Burnett makes it clear in A Little Princess’ earliest chapters that Sara’s “spoiling,” if we must call it that, comes from a deep bond between father and daughter. For the first seven years of Sara’s life, they have only had each other in a foreign country, in a culture where they are treated as superior but remain minorities and might not be well-received outside their home (the Sepoy Mutiny was less than 50 years in the past when A Little Princess was published as a novel, about 30 during its serial publishing). Captain Crewe has likely kept Sara close, physically and emotionally, since losing her mother, presumably in childbirth (the 1995 film references Sara’s deceased baby sister).

Gold Barely There, or Struggling to Sparkle?

When we meet her then, Sara reads less as spoiled and maladjusted, or neurodivergent, than a child entwined with her only parent. But this tendency could read as an infinity trait, too. Neurodiveregent children already tend to relate better to adults than other kids. Sara is one such child. Couple this with her keen intelligence and “mature” interests (e.g., languages, religion), and consumers see infinity traits blossoming almost before her story begins.

However, Sara’s ND-coded traits, and her identity as a powerful infinity heroine, don’t come out fully until she’s taken from the familiar. She and Papa leave India for London, where Sara will attend Miss Minchin’s Select Seminary for Young Ladies. Presumably, she’ll be there for the next decade while Papa discharges military and other obligations in India, various African nations, and other impractical, inhospitable locales.

Sara has no objection to boarding school itself. She’s a bright girl eager to embrace the experience and please her father. Yet transitioning from a world in which she is Papa’s “little princess” to a much bigger one where love might not come so easily, causes some natural trepidation. The 1995 film shows Sara brooding at the ship’s rail on the voyage to New York City (a change from London, as in the book). Later, the film’s camera angles so she appears to shrink while staring up at Miss Minchin’s front door.

Right after the “shrinking” episode, Sara runs up the front steps, smiling at Papa and grabbing his hand. Similarly, the 1939 Shirley Temple version of the story shows Shirley’s Sara tilting her chin and determining to be her daddy’s “good soldier,” while the novel shows Sara putting on her most polite face and voice for an immediately impressed Miss Minchin. But these cues coupled with Sara’s introspection in the book that Minchin is “sickly sweet,” and her hesitation to follow Papa and Minchin in both films, signal she’s “masking.” Both males and females on the ND spectrum can mask, but females tend to do it more frequently. Females are more adept maskers because they are better “mimics” or “actors” than males, and because “society demands social interactions between girls.”

Sara’s School Supplies: Books, Inkwell, Quills…Mask?

Again, some of the “mask” is typical for Sara’s situation. She’s sweet and polite. She’s mature enough to recognize the separation is as hard for Papa as it is for her, and in the case of the films, he’s actually leaving for war. It wouldn’t be out of line for a consumer to say, “This girl is not ND. She’s being brave for her dad. It’s heartbreaking, but not a signal of a disability.”

Other consumers though, will likely see Sara differently. Real infinity girls will probably catch hints of Sara’s mask much sooner than Burnett or film directors could’ve anticipated. More than their male counterparts, infinity girls can “mask” because like Sara, their interests and behavior can be handwaved as girls being girls. If girls hesitate to do new things, it’s because they’re careful. If they throw themselves into languages, religion, or other academic subjects, it’s because they love to learn. If they cling to Dad or Mom, it’s because they’re obedient or understand Mom and Dad are safe when the world might not be.

Furthermore, infinity girls mask because they tend to understand on a different level than boys that the alternative won’t be well received. In A Little Princess, for instance, Sara muses that she could tell Papa what she’s really thinking about Miss Minchin–she’s a phony–or being left at school–she’s unsure at best and hates the idea at worst. But she won’t, Sara decides, because to do so would invite unpleasant consequences. So like infinity girls before and after her, Sara keeps her mask on and continues as a princess in exile. Her infinity traits remain unknown in that no one knows she’s struggling under the mask. And Sara, as her father’s “princess” who must now take a “warrior” mantle, can’t or won’t take the mask off.

Wearing a Heavy, Hidden Crown

Along with her “warrior” mantle and mask, Sara gradually takes on a new facet of an old identity once alone at Miss Minchin’s. She has always embraced her role as her father’s beloved daughter and “princess.” The 1995 film clarifies her belief that she, and all girls, can be princesses once Papa confirms, “You are, and always will be, my little princess.” In school though, Sara needs a way to cope with losing her parent so she can focus effectively on academic and social demands. Over time, she behaves as a princess as much as possible, so much that her peers begin thinking of her as a princess. Youngest student Lottie Legh says it out loud on more than one occasion.

Note Sara doesn’t actually believe she’s a princess, despite cruel misuse of the title from Minchin and bullying student Lavinia. Her engagement in the fantasy is also not completely ND-coded. It’s a coping mechanism a neurotypical girl might use too, if that girl were privileged, creative, and a bookworm. Remember though, ND girls are given to imaginary play beyond the “typical” age, whether that involves imaginary friends, worlds, identities, or some combination. Anne Shirley engaged with “window friend” Katie Morris at ages 12 and 13; Mary Lennox wasn’t given to this type of play but related to animals and plants through personification. Sara engaging in “play” that casts her as a “princess” in late childhood and preteen years then, would be unusual for a typical adolescent. Given her external situation plus other traits, it feeds her coding.

As with Mary and Anne’s ND traits, Sara’s “princess identity” sets her up to succeed and fail by turns. This is not as apparent in the first part of Sara’s story, while she lives the privileged, externally “royal” part of her life. Yet it lays the groundwork for her to act heroically later. For instance, when Sara tries to tell Miss Minchin she is already fluent in French, and innocently asks if she must take classes in it, Minchin assumes the girl is acting like an entitled brat. She takes the misunderstanding personally when Sara explains herself, in French, to Monsieur Dufarge and the French instructor sides with her. Later, Minchin accuses Sara of rubbing her privilege in the other girls’ faces when the latter changes a story’s depressing ending during a required reading hour.

Sara is never openly defiant during these and other confrontations with Minchin. Real-life infinity girls who experience “black and white thinking” may recognize her dilemma. She must maintain commitment to the truth, but also must not disrespect anyone, because disrespect is wrong no matter what. Here, Sara “fails” in that maintaining “princess” behavior in the face of an enemy with power over her, costs her mentally and emotionally. That price may in fact be too high for a girl her age to pay, and is likely higher than she estimated. Yet as Sara discovers later, she “succeeds” because her “princess identity” protects the fullness of her true self, mask or no. It protects her in the eyes of her peers, although her friendships are not always what she might have hoped for.

Social, Yet Set Apart

Sara Crewe is our most social infinity girl so far. Charity, the writer and moderator of the Funky MBTI website, pegs her as an Introverted Intuitive Feeling Perceiver (INFP), indicating although Sara is introverted, she has high levels of intuition and understanding. These let her “read” people, as she did Miss Minchin upon their first meeting. Sara becomes somewhat popular with most of the students at her new school in a short time. She’s not close with them as Anne was with Diana, but she’s so emotionally generous, most peers want to be close to her even if they can’t give her the emotional intimacy she needs. Additionally, despite Sara’s wealth, most peers don’t stay on her good side for access to her possessions. They genuinely like her for her compassion and exuberance, both much-needed in Miss Minchin’s rigid, unforgiving environment.

Sara returns her peers’ affection, becoming “best friends” with one or two, as well as she knows how. Sara’s first friend is Ermengarde St. John, a “hapless” classmate the other girls avoid because she’s fat, shy, and inept at schoolwork. Ermengarde’s father is an authoritarian academician, and Miss Minchin delights in threatening the girl with telling him about her continued poor performance, knowing she’ll be shamed and punished. So when Sara takes Ermengarde under her wing, promising to tutor her, the other girl is as awestruck as a peasant whom a real princess has given jewels or a fine cloak. It’s a win-win situation in many ways. Ermengarde’s schoolwork improves, as does her social circle because the other girls see her differently once she gains Sara’s approval. Sara gains her first real, same-age friend because she sees Ermengarde as an equal as best she can. Miss Minchin loses her power over Ermengarde, and Sara wins against her yet again, coming ever closer to exposing this villain for who and what she truly is under her veneer.

Despite all these positives, Sara remains “set apart” from Ermengarde, very much in a “princess” role, though she doesn’t mean to be there. Like many real-life infinity girls, Sara wants and tries to relate to Ermengarde as a peer. In fact, that’s what she’s doing as far as Ermengarde knows, because neither girl has had much experience in that field. But Sara actually relates to Ermengarde more as a teacher or mentor, more as someone making her “acceptable” to others.

Many real infinity girls do this if, or because, they don’t understand or acknowledge the mental and emotional boundaries between themselves and adults. They’ve heard or been told they are “little philosophers” or “little professors,” so they slide into that mold, if unconsciously. Failing that, they seek to help others out of genuine compassion, as Sara does, but their maturity makes this come across as “teaching” more than “helping.” Again, Ermengarde doesn’t seem to mind, and again, the friendship holds up, at least to a point. But when this type of friendship is tested and privilege crops up, both girls find it hasn’t done them any favors.

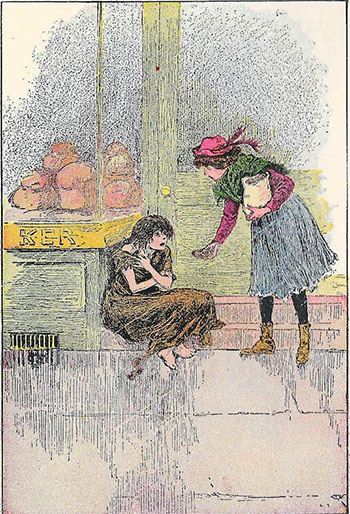

Sara finds herself in a similar bind with her other close same-age friend, Becky. Becky is the school’s abused scullery maid, and depending on adaptation, either Cockney English or African-American. In either case, she is lower class and considered a second-class citizen even in America (the 1995 film, the only one set in the U.S., takes place in 1914). From day one, Sara is saddened and frustrated at Becky’s mistreatment, and wishes to be friends because she understands the other girl is her age and might have some of the same desires and interests, class and racial differences or not. But as with Ermengarde, Sara’s innate privileges block her from equal friendship with Becky, until externals intervene.

A Princess Dethroned

Sara’s friendship with Becky begins while the former is still considered “princess” of Miss Minchin’s, and called so in various situations. “I told her that’s what you were,” Lottie says innocently when Lavinia makes fun of Sara’s status in the 1995 film. Most of Sara’s peers go along with this, whether in the book, a film, or a stage play (A Little Princess has been adapted into two off-Broadway musicals). Yet none seem so eager to embrace Sara’s “royalty” as Becky. Depending on adaptation, Becky is either Cockney and therefore a member of one of the lowest classes in England, or Black American From day one, Sara is struck by the disparity in the girls’ lifestyles despite their being the same age (films age both girls up to between 10 and 12). True to her infinity girl nature and privileged upbringing though, she isn’t as successful as she could be in beginning a true girlhood friendship with Becky.

Sara makes some friendly gestures to Becky while her wealth is intact, such as inviting her to listen while the former spins her famous stories for classmates or, in the films, giving her gifts of food, sweets, or sturdy, warm shoes. However, this reads as another “infinity” friendship wherein Sara takes the role of “giver” or “adult provider,” until tragedy forces both girls onto equal footing.

When Sara’s father dies after a recent investment in African diamond mines goes bust, Miss Minchin is only too thrilled to tell Sara she is alone in the world and penniless, since the British government has seized all his assets. Minchin will keep Sara at the school as an act of “charity,” and Sara will work there as a servant indefinitely, until she can pay off the debt she has incurred. Miss Minchin will seize everything she owns–“your clothes, your toys, everything…though it will hardly make up for the financial losses I’ve suffered.”