The Ambiguous Morality of Œdipus Rex’s Iocastê

Sophocles’ play Œdipus Rex sits among the greatest works in the ancient world. It reveals a desire for a deeper understanding of human emotions and its relations with the spiritual world from humanity’s beginnings. It shows human desires in word and deed, the implied and the possible. Œdipus Rex represents well the works of the ancient world. Interestingly, the human psyche’s wants and flaws most obviously emerge, not in Œdipus, but in the femme fatale of sorts, his wife, Iocastê. Her struggles with her husband illuminate themselves most particularly in questions of her morality.

Is she unaware of her true relations with Œdipus? Is she in denial? Is she in love with Œdipus? Or rather in love with the lifestyle to which Œdipus gives her access? Is it some of these? All of these? Some or all of these elements? These questions demonstrate Sophocles’ use of ambiguity to highlight Iocastê’s actions and real or possible motives. In doing so, Iocastê becomes an everywoman in Œdipus Rex to show the complex, multiple and even competing motives that people have. 1

Basic Background of Iocastê

Laïos and Iocastê gave birth to Œdipus in Thebes. 2 Afterwards, Apollo in a prophesy revealed that the child would kill Laïos and marry Iocastê in a union that would bear children unless Œdipus died. Thus, Laïos ordered the child killed. 3 He pierced and tied Œdipus’ ankles. Iocastê then gave Œdipus to a shepherd who brought him to the Kitharion Hills near the border with Corinth, where the child would have died. 4 But the shepherd took pity upon Œdipus and willed for him to live. 5 The shepherd gave the child to a messenger-shepherd from Corinth instead. 6 Œdipus found his way to the Royal House of Corinth and was raised as the son of King Polybus and Queen Meropê. They named him Œdipus because of his swollen ankles when found. 7

Up to his adult life, Œdipus had no reason to believe that his parents were anyone else. But one night, during a feast, a drunk man came to Œdipus and shouted to his face that he was not Polybus’ son. Even after parental reassurance, Œdipus felt somewhat uneasy about his birth, so he went to Delphi for divine council to ask about his parents’ identity. Instead, the gods revealed Laïos’ prophesy to him. For fear that he would fulfill this prophesy, he fled from Corinth. 8

Œdipus came to a three-road intersection that led to Thebes. 9 There, Œdipus crossed paths with a chariot with five men, including Laïos, en route to a pilgrimage. 10 The chariot’s herald ordered Œdipus off the road and a charioteer approached to push him away. Enraged at this, Œdipus toppled the chariot and killed all he could, including―with his identity unbeknownst to him―Laïos. 11

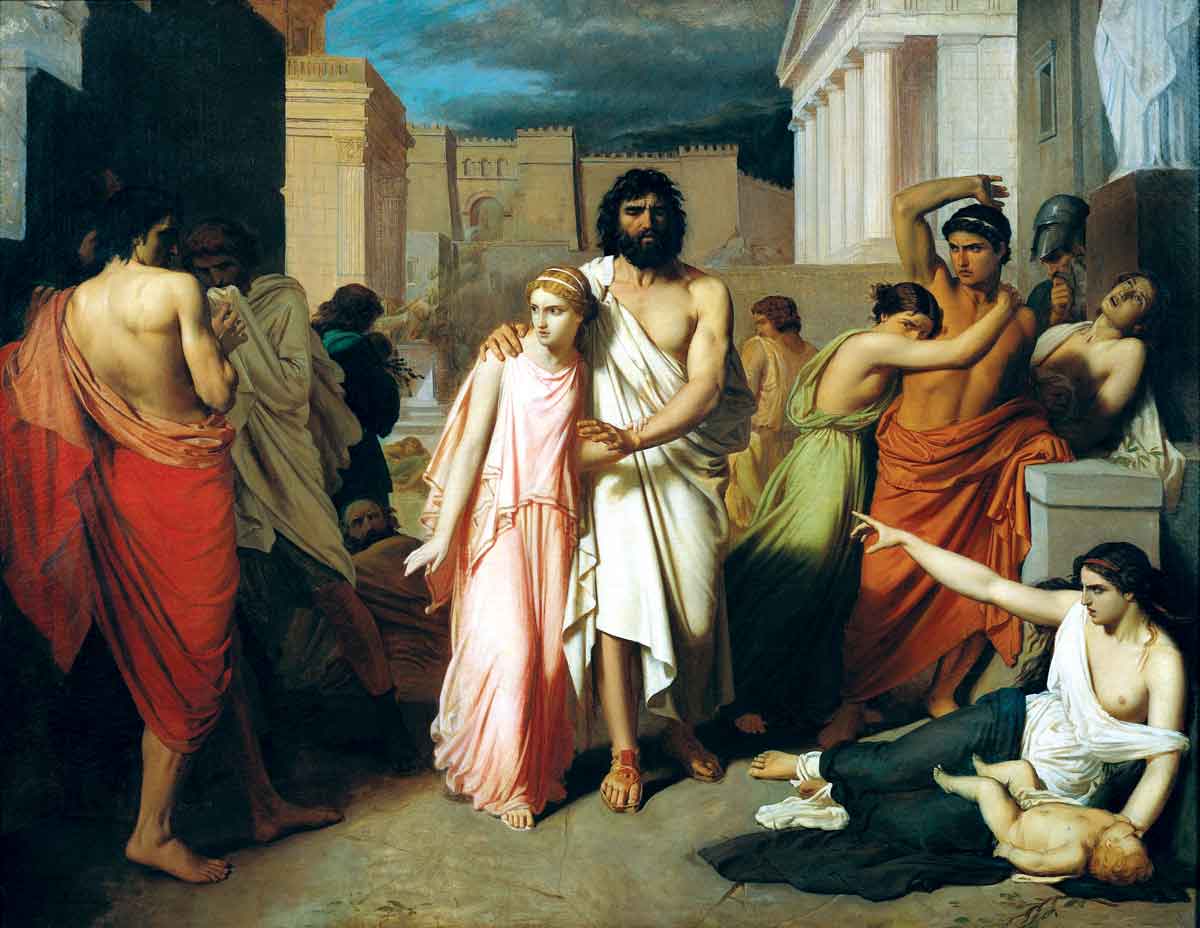

None in Thebes could attend to Laïos’ death because in almost-immediate succession, a Sphynx began her torment along a main road to Thebes. The Sphynx only permitted passage to travelers with the correct answer to her riddle and ate any who answered incorrectly. Thebes so desired to remove the Sphynx that Creon offered the hand of Iocastê―and in effect the Theban crown―to the one who solved this riddle. Œdipus correctly answered the riddle. For his cleverness, Iocastê became Œdipus’ bride, 12 Œdipus became king. Iocastê and Creon acted as co-rulers alongside him. 13

In Œdipus Rex, Iocastê first appeared as Œdipus and Creon argued, of which she stopped. 14 But she wanted to know from Œdipus what caused the argument. Œdipus claimed that Creon charged him with Laïos’ murder. But when Iocastê pressed for a reason why, he could only say that Creon―without basis―had Teiresias make the claim via supposed prophesy. 15 In any case, Iocastê dismissed the notion of prophesy because prophesy claimed that Laïos’ son would kill him. Instead, marauders killed Laïos. Laïos pierced the son’s ankles and a servant left the son to die. Thus, the prophesy held false. From this, Iocastê concluded that prophets and prophesy held no value and that God would show what he would in his own way. 16

Far from relieving Œdipus, he felt that too many details from Laïos’ death fit with how he killed much of the chariot’s entourage. Œdipus ordered a survivor of the attack on Laïos brought to the palace. 17 Œdipus hoped that this charioteer’s account aligned with Iocastê’s account of a band of marauders, and not a lone man. A lone attacker would prove that he murdered his father and worse! 18 Iocastê even offered her prayers and an offering to Apollo for guidance and help for Œdipus, Thebes and its leadership. 19

Later, a messenger from Corinth went to Iocastê and Œdipus and announced that Polybus died. 20 Œdipus felt an initial relief―as one half of the prophesy proved false―followed by a dread that the other half of the prophesy could hold true. But, Iocastê urged Œdipus not to worry further, to live for now. She gave assurances that nothing lasted forever and that none but fate ruled over all. In trying to relieve Œdipus’ specific concerns about his birth, Iocastê noted gently that his fears crossed the minds of many reasonable men in dreams. 21

Even with assurances, Œdipus still remained fearful that he would marry Meropê, the woman he still believed to be his mother. 22 Iocastê then tried to shift Œdipus’ focus on the father’s death. 23 The messenger told Œdipus that Polybus and Meropê did not give birth to him because he saw Œdipus’ motive for leaving Corinth and thought this information would motivate his return. 24 They adopted him and raised him as their own son. The messenger first encountered Œdipus in Kitharion’s crooked pass in his flock-tending. 25 Another shepherd gave him to the messenger. The messenger referred to the shepherd for the rest of the tale for Œdipus’ origins and the true identity of his parents. 26 Further, the messenger said that Laïos served as the shepherd’s master. The shepherd that saved Œdipus and the shepherd for whom Œdipus had sent seemed more like one and the same man. 27

Œdipus in his curiosity asked Iocastê if she knew of this shepherd. Iocastê said to forget about the whole affair and that the shepherd served only to distract. She abandoned her gentle guidance. Confused, Œdipus wondered why she said this right before the crux of his investigation. Iocastê demanded that he investigate no further. She even hinted at their identities when she said that to bear her own pain sufficed. 28

This same Œdipus with great perception did not perceive her hint. Desperate, Iocastê implored him not to talk to the shepherd. But Œdipus insisted that he needed to reveal the truth. Iocastê exclaimed that she did this for his own good. Œdipus stubbornly refused a third time. Defeated, Iocastê said to Œdipus that “you are fatally wrong! May you never learn who you are!” 29

Œdipus still remained oblivious, even after Iocastê left the room, having lost face. 30 Thus, Œdipus, who thought a slave mother gave birth to him, felt ready to face the truth of his birth, come what may. 31 But Œdipus did not expect that he was the son of Iocastê, the woman he called his wife. 32 Œdipus burst into Iocastê’s quarters only to find that she hanged herself. 33 Once he lowered Iocastê’s body, Œdipus took a broach from her dress and blinded himself with it. 34 He lamented at his sorry state, wished for his death, bid his four children farewell―particularly his two daughters―then exiled himself from Thebes. 35

Iocastê the Naïve

Iocastê can show herself as completely a victim of her circumstances. That the prophesy, the failure to kill Œdipus, Œdipus’ killing of Laïos, Creon’s reward of her hand to whoever could solve the Sphynx’s riddle and her marriage to her son all remained out of her control. That she remained completely oblivious to everything transpiring in her life. That she had no knowledge of Œdipus’ identity until Œdipus dug where he should not have. That as a consequence of ignorance, Iocastê married her son and created four children with him. Thus, she so recoiled in horror in what became for her the likely outcome, that she could not bear to live one moment longer after this incestuous discovery.

This version certainly holds textual plausibility. Iocastê became open to the sways of any who would protect her after Laïos’ murder and the stress that the Sphynx inflicted upon the city in short succession. The city has no obvious successor and no way of combatting the Sphynx. Creon used the one advantage Thebes had―Iocastê’s new-found marital prospects― to rid Thebes of the Sphynx’s scourge successfully. The shock of tragedy followed by the sudden rush of joy from Œdipus’ victory over the Sphynx easily could have blinded Iocastê and everyone else to glaring flaws.

In order for Iocastê to have this view of her world around her, it requires that she overlook these clues. For one, the fact that she married Œdipus, whose name means “swollen ankles” would certainly trigger Iocastê’s curiosity if more discerning. The fact that she first met the adult Œdipus directly before their marriage, about twenty years after his birth from her would otherwise add to this suspicion. Iocastê would have to dismiss the shepherd leaving the palace staff as mere coincidence. Her verbal slip to Œdipus that the thought of marriage to the mother occurred to many men would need to manifest as an ironic coincidence. Iocastê would also have to overlook Laïos’ death and its close alignment with the prophesy, though the variations in accounts help with having a blissful ignorance. Perhaps it lies in these variations that kept Iocastê in this ignorance. Indeed, her claims to distrust prophesy and man to be at the whim of fate stand consistent with this interpretation and desire. Finally, she would need to be under the impression that the shepherd followed Laïos’ orders and killed the infant Œdipus. Thus, Iocastê would have made her prayers to Apollo genuinely, in good faith toward an end without a curse. Otherwise, she would have very little basis to have such naïveté, which would give an impression of a more sinister side to Iocastê. Ultimately, this image of Iocastê lacked any perception until affairs between her and Œdipus transpired well beyond a point of no return and what had transpired became obvious to all.

Iocastê in Denial

Iocastê also presents as someone in denial. The struggle of Thebes to rid itself of the Sphynx and Creon’s desperation―to where he offered Iocastê’s hand to the man who rid Thebes of the Sphynx―implies a strife within Iocastê too. This stress contrasts in equal measure only with the relief that Œdipus provided in ridding Thebes of the Sphynx. Thus, she gained an emotional stake in a pleasant marriage. As such, she resisted believing that she gave birth to her husband. She clung to any possible shred of evidence that could point away from this conclusion. She claimed a band of marauders killed Laïos as opposed to one man. She highlighted that Meropê’s death prevented Œdipus from marrying her according to his prophesy and could thus be dismissed. She used these previous dismissals to claim that Teiresias’ prophesies held fruitless.

Her reasoning seemed sensible enough, to where Œdipus seemed to agree with her assessment at times. But the Corinthian messenger’s denial of Polybus’ and Meropê’s paternity of Œdipus changed Iocastê’s calculus. This undermined her work. Iocastê could only claim that nothing definitive about Œdipus’ origins had been said. This made any talk of incest malicious gossip. But the shepherd’s testimony threatened this. Thus, Iocastê insisted to Œdipus that he not talk to the shepherd. However, Œdipus deprived her of any deniability, any opportunity to save face, to continue this illusion in talking to the shepherd.

Iocastê’s issues caused by the Sphynx certainly caused her to let her guard down, much like if she had simply taken everything at face value and did not investigate deeper into other issues. But unlike mere ignorance, her seemingly good fortune of marrying the new king and savior of Thebes created for her an investment in being the Queen of Thebes. Thus, she has an explanation for ignoring obvious clues: she wanted to believe the best and had an emotional need to find any evidence that could dispel the worst conclusions about her relationship with Œdipus. Once she found such evidence, she would look at it in the best possible light, then dismiss less savory possibilities.

Iocastê’s embrace of this view, while certainly plausible, requires a key element from her: complete good faith as an actor. She would still need to believe that the shepherd killed her son. Any world where she does not believe this is a world that requires her to act in less than good faith. An Iocastê in delusion requires that she act from a position of helpfulness. She would need to rise above court factionalism, favoritism and politics in her regular royal life. This becomes of greater importance because of her co-ruler status, which makes court factions, favorites and politics a direct interest to her. Maintaining such a position in court―as with any clique or social setting―remains difficult enough when no power and influence implicate themselves. How can such a position remain tenable when in power? How much more difficult!? In this light, her prayers to Apollo remain genuine and show more of a spirit of desiring clarity.

Iocastê the Lustful

But Iocastê rather, has a character interpretation such that she had full awareness that she married her son. A disturbingly strong case emerges for this reading, along with its implications. Clues abound through the text: a man whose name means “pierced ankles”, about twenty years after Œdipus’ supposed death defeated the Sphynx, and won Iocastê’s hand in marriage. When put like this, this seems more than mere coincidence. But here there exists a perverse feature: Iocastê cooperated completely with this incestuous arrangement and said nothing to Œdipus of his identity because she genuinely fell in love with her son, knowing fully of his identity. It seemed as if Iocastê gained a greater enjoyment―whether out of enjoying risk, the illicit or both―out of holding this secret and keeping it all to herself.

This view implies a similarity in temperament between both Laïos and Œdipus, in that both have a cleverness. Œdipus showed it in solving the Sphynx’s riddle. But it also implies a swiftness to anger and an impulsiveness. Œdipus certainly showed this wrath and impulsiveness in killing much of Laïos’ chariot’s entourage en route to Thebes, and in his interrogations of Teiresias, Creon and the shepherd who saved his life. His willingness to marry an older woman, presumably at least twenty years his junior, in order to seize the throne without any further inquiry or discernment, though understandable given the glisten of the Theban crown, showed the greatest impulsiveness of all. More so, Œdipus’ created an inquiry into the origins of the Theban curse and his pursuit of the truth until he discovered it. This incestuous truth led to her own demise.

An Iocastê that knowingly held an attraction to her son would gravitate to his cleverness, as she did to Laïos. She also invariably bore the burdens that either impressed upon her, others and ultimately themselves. In this light, Iocastê’s dismissal of the prophesies and her proclaimed belief in fate’s governance served not to express true beliefs but―whether out of shame, selfishness and appearances, something else or some combination of these―to conceal the truth. Indeed, Teiresias, in noting that Œdipus’ true parents thought his prophesies and him reasonable enough, contradicted her claims in her dismissal of prophesies. Iocastê imploring Œdipus not to talk to the shepherd represented her only moment where she removed her façade while alive. She demanded this not because she wanted plausible deniability for herself, but before the public. She wanted to keep her perverse love for Œdipus alive for as long as possible. Œdipus’ extraction of the information from the shepherd exposed his incest and killed any chances for Iocastê to remain as before. Thus, whether out of shame, because she did not wish to live as less than a queen or some other reason, Iocastê killed herself.

This Iocastê requires an essence of wickedness. She cleaved to the baser things in life. The shepherd here necessarily told Iocastê that he did not kill her son: too much plausible deniability would exist otherwise. Though there existed a sensual side to Iocastê, she projected this intimacy in disturbing ways, with her and Œdipus creating four children the least of them. The strife that Thebes endured with the Sphynx’s terror followed by Œdipus’ reprieve, by contrast did not dull Iocastê’s senses. If anything, they enhanced them. Œdipus’ rescue made awoke Iocastê’s full passions. She romanticized Œdipus in secret as the hero-rescuer. This Iocastê also had many secrets that she took to her grave. This proves necessary in order to have this form an inner world consistent with the play’s reality. As a consequence, her prayers to Apollo are harder to be seen as being completely in good faith: since she knows that Œdipus fundamentally is the source of the curse, her prayers have more of a special pleading in mind. A pleading where the curse can be lifted with no consequence to Œdipus, the city and ultimately, to her. She would will for all to live in blissful ignorance as she continues her romantic tryst with her son.

Iocastê the Queen Dowager

This version of Iocastê also married her son Œdipus knowing fully that she gave birth to him. But no romantic love for Œdipus existed on her part here. In fact, whether she had any love for him―even normal, maternal love―remains an open question. Indeed, the first best evidence of a lack of maternal concern: though Laïos ordered Œdipus’ killing in his infancy, nowhere does the text suggest that Iocastê objected to it, or even express a concern that to kill Œdipus held as wrong. Further, the force of Hellenic divine intervention via Apollo gave only indications of a moral righteousness in killing Œdipus. Laïos’ death and the terror of the Sphynx, seen in this lens, threatened Iocastê’s access to power. Creon’s offer of the Theban crown coupled with Iocastê’s hand in marriage offered Iocastê her only way to keep her access to power in the long term. Thus, Iocastê married Œdipus, knowing of his identity, because it allowed her to keep the influential position that she had when married to Laïos.

Through this lens, Iocastê similarly, deliberately concealed the truth of Œdipus’ identity in saying that she held no credence to prophesies and that fate decided all things. Indeed, Teiresias noted that Iocastê believed his claims. But why Iocastê concealed presents as a more vexing issue. Iocastê had motive to keep her husband in her lustful state and therefore to keep her power. All of her apparent loving actions―their four children, her professions of wanting the best for Œdipus, her seeming concern for Œdipus and the like―paint more of a façade, a veneer of concern and love in order to hold onto power in Thebes. If Iocastê had to tend to her son’s marital needs, this was a price Iocastê felt content in paying. Perhaps her prayer to Apollo asking for guidance and help for Œdipus illustrates her one, brief possible moment of remorse. Whether Iocastê asked Apollo to help Œdipus weather the coming storm―which would permit the status quo―or for a life where he had a happy end, she showed a shred of an apology. But as she did not change course, this offered scant consolation for her in the end. She begged exuberantly for Œdipus not to talk to the shepherd, which represented her final grasp for power. In this light, when Œdipus did not give Iocastê any plausible deniability against the incestuous conclusion, she killed herself in order to avoid accountability for her actions toward keeping power wantonly.

The Iocastê portrayed here reflects an image of a cold, calculating, politically shrewd woman who clearly favored the end as opposed to how to reach the end. Thus, similar to her lustful state with similar reasoning, she would need to know that her infant son had lived. This version of Iocastê knew no bounds in who she used and what she did in order to achieve her goals and gain and maintain power. She also commited to her actions without apology and wanted no accountability for her wrong actions. She is Machiavelli’s Prince incarnate.

Iocastê the Confused

Iocastê alternatively reads as an extraordinarily confused character who does not embody one specific character mold but rather embodies elements of all of these theses regarding Iocastê’s character. These separate parts create the whole where confusion results. Iocastê first met her son as an adult about twenty years after his birth and learned that her husband-to-be was called “pierced ankles:” the way Laïos intended for him to die. This matches with the lust or Queen Dowager thesis. But Œdipus became her husband-to-be because he unwittingly killed his father Laïos and ended the Sphynx’s highwayman-like terror by solving her riddle. This fits with a thesis based on naïveté or delusion.

There likely existed feelings within Iocastê that made her wonder if she wedded her own son: the not-so-coincidental circumstances of his name and age compared to hers and his likely-similar deportment when compared to Laïos. But since the text makes no direct impression that Iocastê knew that Œdipus remained alive, for her, it made for an interesting, passing coincidence in her mind but nothing more. Even if she did know her son remained alive, her marriage’s circumstances remained a coincidence in her mind all the same. She expressed her skepticism in prophesy truthfully; Teiresias spoke of Laïos’ feelings when he said to Œdipus that his parents thought him sufficiently credible, without knowing Iocastê’s, whether through her silence or her own deceit. Regardless, she kept her true feelings about prophesies to herself. Thus, she made her prayers for help and guidance for Œdipus, Thebes and the Theban leadership in order to resolve doubts within her own mind. On some level, she knew that something within the narrative in her life did not feel sound, but to that point felt content to ignore the issue. But Œdipus delved deep into his investigation. This made these doubts more profound in her mind and bothered her to where she felt she needed resolution. She definitely, eternally gained it.

Iocastê felt her confusion reach its apex when Œdipus’ interrogation of the shepherd became imminent. There, she insisted and begged for Œdipus not to talk to the shepherd to retain a sense of plausible deniability. This places this element among the elements of ignorance and denial. But beyond this, her impetus toward a sudden furious burst from her remained a wish to return to how she lived her life―and how all lived theirs―before Œdipus’ investigation, and ultimately before Apollo’s curse. Ultimately, the chain of events in motion proved unstoppable: the more Œdipus applied pressure to find Laïos’ killer, the more Iocastê had to conclude that it was Œdipus. Œdipus’ refusal of her request not to talk to the shepherd proved the death knell for any plausible deniability for her. Her suicide from shame of the inevitable, incestuous conclusion became her end.

To its merit, this view permits the incorporation of self-interest, romantic feelings, delusion and naïveté on Iocastê’s part. More to the point, unique to this view, it also allows these elements of self-interest, love, delusion and naïveté to feed into each other and to reinforce each other. It allows the reader to see Iocastê as a woman who does not want to believe the worst, because of the disastrous moral consequences. She did not wish to believe because it would detract from her position as the queen, because she truly loved Œdipus and the idea of marrying a son spelled disaster. Ultimately, she refused to believe because she thought the worst simply could not occur unto her. Most of all, the reader can see Iocastê as a completely relatable human who fell into grievous misfortune. It is fitting that Iocastê prayed for help and guidance for Œdipus: this served as a way to apologize to her son for trying to kill him and an appeal for a better future. This serves as the summit and totality in this view of Iocastê.

Iocastê exemplifies the tensions present in humanity where conflicting moral and human interests collide. It shows the dangers of excessive attachment to the overtly political and human emotions and the struggles that humanity holds with the spiritual in one woman. She highlights starkly humanity’s fallen nature. She illustrates that the many moral issues confronting the Ancient Greeks nearly twenty-five centuries ago still echo unto humanity today. Above all, she serves as a reminder that Iocastê’s world remains not so distant from our own and transcends throughout the ages.

Works Cited

- All of the primary source material comes from SOPHOCLES, Œdipus Rex, in THE ŒDIPUS CYCLE passim (Dudley Fitts & Robert Fitzgerald trans. & eds., 1939, 1941 & 1949) (c. 429 B.C.) (hereinafter Œdipus Rex). ↩

- Compare Œdipus Rex 38-40, to Œdipus Rex 67-68. ↩

- Compare Œdipus Rex 38-40, to Œdipus Rex 42, and Œdipus Rex 67-68. ↩

- Œdipus Rex 54-55, 60-64. ↩

- Œdipus Rex 64. ↩

- Œdipus Rex 59, 62-64. ↩

- See Œdipus Rex 48-49, 51, 53-55. It should be noted that his name literally means “swollen ankle” in Ancient Greek. ↩

- See Œdipus Rex 42. ↩

- See Œdipus Rex 43. ↩

- Compare Œdipus Rex 8-9, with Œdipus Rex 40. ↩

- Compare Œdipus Rex 40, with Œdipus Rex 43. ↩

- See, e.g., Œdipus Rex 5, 9, 80 for allusions to “the famous riddle.” ↩

- See Œdipus Rex, 31. ↩

- See Œdipus Rex 33-34. ↩

- Œdipus Rex 37-38. It should be noted that Teiresias and Œdipus argued viciously over Œdipus’ identity, which included Teiresias claiming presciently that Œdipus was the curse that plagued Thebes. To boost his claim’s credence, Teiresias said to Œdipus that his parents thought him reasonable enough, which made Œdipus question who his real parents were. See generally, Œdipus Rex 15-25; 63-64; 71, for further details. ↩

- Œdipus Rex 38. ↩

- See Œdipus Rex 39-45. ↩

- See Œdipus Rex 44-45. ↩

- Œdipus Rex 47-48. ↩

- Œdipus Rex 48-49. ↩

- Œdipus Rex 50-51. ↩

- Œdipus Rex 50-51. ↩

- Œdipus Rex 50. ↩

- Œdipus Rex 52-53. ↩

- Œdipus Rex 54. ↩

- Œdipus Rex 55. ↩

- See Œdipus Rex 55-56. ↩

- Œdipus Rex 56. ↩

- Œdipus Rex 57. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Œdipus Rex 57-58. ↩

- See Œdipus Rex 63-64. ↩

- Œdipus Rex 68-69. ↩

- See Œdipus Rex 69, 72. ↩

- See Œdipus Rex 73-77, 79-81. ↩

What do you think? Leave a comment.

I read this in high-school and found it devastating. Now being a father, I should probably read it as the pain of Oedipus would probably strike me even deeper.

I would imagine so; emotive feelings are always deeper when relatable on some level.

Jocasta has no-one left to blame but herself.

That certainly can be a natural corollary if you have taken a less charitable view of her especially if seen as a lover of power.

I’ve read some criticism stating that some of the drama is a bit over the top, and while I wouldn’t agree and, more importantly, couldn’t possibly begin to imagine myself in the same situation, I guess it was in vogue at the time that the heroes would suffer so much when they’d find their worlds turned upside down that they would impose on themselves severe sentences such as mutilations or death.

The key to the relatability is human emotion. Knowing some of the historic custom of the age and how Œdipus Rex deviated from these norms also helps.

Thanks for reading.

Iocaste is a pretty strong female character for a work of literature written all the way back in the B.C.’s.

This is strikingly consistent with the blue-blooded throughout antiquity and beyond.

God, I love Greek mythology.

Thanks for the sentiments. So do I.

I think this is what great literature is about- never grows old nor stops teaching.

This is precisely the point I wanted to express. Thanks for reading!

The story doesn’t only make us question the role of god(s),fate, and destiny and whether it’s fair to be controlled by external powers. It also makes us question who we are and whether our personality or character is a kind of destiny. Where’s our human freedom?

Those were definitely the questions that were contemplated by the Athenians of this age. These plays were used in this time as a form of worship for context.

Many questions left with no definite answers. I think they’re worth a pause- some time to reflect and ponder.

This definitely was the spirit of some of the Ancient Greeks. I think there is something definite to the play though. I don’t think it would be to Aristotle’s liking if Œdipus Rex was like this precisely.

I read this back in college and liked the story but found the prose rather dreary – no surprise, since I had the Lattimore translation and I find him a bit tedious, in general.

I can see where you’re coming from; the Lattimore seems to use a more direct translation, which has a certain, Ancient Greek rhetorical flourish. I personally like it, but I can see where someone wouldn’t.

My professor in the university once said, “I’ve been teaching this play in the drama course for more than 3 years, and every time I think I’m done with it, it teaches me something new. Perhaps when it stops amazing me, I will stop teaching it.”

I sent him this article as I believe it might be another angle he hasn’t explored fully yet.

Thank you so much for reading! If you could let me know your professor’s critique I would be most appreciative.

Incidentally, this is the nature of such works; you’ll always find more to take from it.

I think this is what great literature is about- never grows old nor stops teaching.

I can agree to this; there are but a select few works like this.

Sophocles’ tragedies are at the same time both simple and complex. Simple in form but deep in meaning.

Well said! Thank for reading.

As far as dysfunctional families go, I think Oedipus’ takes the cake.

Hence why I put in the Hercules screenshot and quote.

Fate is unavoidable in ancient Greek Tragedy.

Among other themes.

Every time I read an ancient text I recurrently find myself to blame because of the same mistake: being surprised by its quality despite being written so long ago.

I tend to find that the older texts are the more well-written, but that’s just a thought. Hope it’s helpful.

I had to read this for one of my classes because the theme of the course is lost/abandoned children. It’s quite fitting because this is the main theme of the work.

It’s a theme; it’s one of quite a few.

Kudos to Sophocles for taking a really, really messed up Greek myth and making it into something stomachable while keeping the whole “live-action play” theme in mind.

This was originally meant to be a way of worshiping the Ancient Greek gods, for context.

I watched the film of Yukio Ninagawa’s production of this drama many years ago. I believe it was the one in 1986. (The live performance took place for only a few days, but it was filmed.) It was superb. It doesn’t seem widely available, but if you come across it, don’t miss the opportunity. (Ninagawa also directed other ancient Greek tragedies such as Media, and also some Shakespeare plays.)

That would be interesting to see; this play (and the operatic version of this) have a surprisingly decent number of these performances.

My favorite thing about Greek plays is that they enjoy making the characters life absolutely miserable. You think Shakespeare can be tragic. You haven’t read anything like Sophocles. He knows how to write a tragedy.

Not all of them; the Ancient Greeks had their comedies too.

I was just frustrated with how transparent everything was and thus how dumb Oedipus ended up looking for not figuring it all out.

Good observation of the irony; all the more so considering that Œdipus was meant to be a great discerner.

Great article. Got me inspired about something. What if we analyse Oedipus next to Voldemort. They’re victims of the same tragic flaw: the belief that they can outsmart fate.F ate isn’t written in the palm of our hands or in the position of the stars; it is with us in the form of our character.

If Voldemort hadn’t feared Trawleny’s prophecy, he wouldn’t have tried to kill Harry and set him on a journey to destroy him.

If Oedipus hadn’t feared Apolo’s prophecy, he wouldn’t have fled from Corinth, murdered Laius or married Jocasta.

Someone needs to write an article about this on The Artifice.

Contra: in the worlds where things are dated to occur it will occur at som point. No amount of what ifs would change that ultimate fate; it simply wold change the source of the proximate cause.

The only reason the play is famous is because of the Oedipus complex! Either this play is his worse, or Sophocles is a horrible author/playwright.

Hate to burst your bubble, but this was fairly well-regarded by both Sophocles’ contemporaries (most notably Aristotle) and contemporaries. Indeed Aristotle used this play as an example of the ideal play. Freud used the templates of Ancient Greek characters because of how well they were known among the educated in his time. Just some context.

I can definitely see how Shakespeare borrowed from this.

I haven’t heard this before but this wouldn’t surprise me. At some point, there’s a lot of borrowing.

Sophocles did a really great job with the dramatic irony but most importantly a “heroic downfall”.

Fortunately, Œdipus has a bit of a redemption arc in Œdipus at Colonus.

I am really glad my teacher chose us to read this because this story has connections and different emotions to it.

Indeed: one of the observations that I made of Iocastê that holds true for all the major characters of this world.

Strong take on Jocasta. You cannot consider yourself to be a true lover of European literature without reading this pioneering work or better yet going to see a performance. It still works brilliantly when staged.

I definitely should see a production of it. I’ve done a bit of theatre and wrote the piece with the acting in mind in part.

I love how Greek plays from 430 BC still manage to shock and delight me.

This does go toward the play’s timelessness.

I get why so many writers, during so many different art periods, looked up to Greek tragedies.

Verily, Sir Issac Newton did say that he stood on the shoulders of giants. Those would be the ancients.

Sophocles is trying to tell us that Jocasta, Laius and Oedipus struggled against their fate and made it all the worse for themselves, the best we can do is be pious and quietly suffer out lot.

I could quibble a bit with Iocastê (not so much Œdipus or Laïos), but I can see the logic from where you are.

I found myself laughing a surprising bit along with the first half or so of Oedipus Rex before things got into mega-tragic mode.

This was the nature of the tragedy until at least the 19th Century.

Sophocles is brilliant.

I believe this was the overall consensus among his contemporaries and the critics of this age alike.

Forget about Shakespearean insults friends, Sophocles was doing that hundreds of year before little William was a goddamn sperm cell!

It’s interesting that I have seen a number of comments here expressing this general sentiment (though not quite so bluntly as you).

The Greeks knew the human heart’s most ghastly fears.

This is definitely true as to Sophocles.

Indeed, this was practically a spiritual prerequisite for the playwright.

With classics like this, you expect the moment of “ah-ha!” when you recognize how a story impacts the culture you live in, even subconsciously.

Definitely as it pertains to sayings/proverbs/et cetera. It also is an example of the society in which Sophocles lived, in that, the human form was pushed to diverse extremes during this time.

Thanks for reading!

I can’t wait to read more from Sophocles! Turning the remaining of this year into the Greek mythology consumption.

Two of Sophocles’ works are successor word to this one; they are Œdipus at Colonus and Antigone. Those would be good places to start.

Thanks for reading!

I read it not too long ago. I didn’t get enough of a rounded picture and I wanted more of Jocasta and Oedipus’s marriage for the eventual revelation to have absolute resonance.

Part of this issue is due to strict adherence to Aristotle’s Three Unities (Time, Location and Story). This may be why it’s not resonating in the way that you would want or expect by modern conventions.

Thanks for reading!

Proves that no matter how smart you are, your wife / mom will figure it out first.

In this case, sadly both!

The parallels between this and Frankenstein are interesting.

In what way? Genuinely curious as to how you connected these two works.

Easily one of the best classics I have read from that time period.

I would tend to agree, though I do think that The Odyssey ranks up there too.

Oedipus is not alone in his hubris, Jocasta too is guilty of presuming to know better than the gods!

I certainly can see that, depending on the interpretation of Iocastê that you would want to view, but I see this as more equivocal.

This is obviously the origin of our modern soap operas. So much impossible things happened, and I love it.

I think that might be a bit of a leap: you have a 2200-year gap from these two art forms.

An interesting analysis of one of the most intriguing characters in Greek mythology. A lot of attention is paid to Oedipus, rightly so, but it’s nice to see the spotlight pivoted to Jocasta as well. Her level of awareness and motivations are often left opaque enough for the viewer/reader to ponder endlessly without ever reaching a fully satisfying conclusion to the initial inquiry.

Thanks for reading and your comment!

I think that this was one of the angles that Sophocles had in mind in this Ancient Greek version of a liturgy (as it was one of their forms of worship in Greco-Roman Paganism).

Congratulations on such a thorough analysis of one character’s merit and arc, especially a lesser-known character (to some of us, anyway. My English classes didn’t focus a lot on mythology, although I wish they had).

Thanks for reading, your comment and your gracious compliments!

When I studied literature, particularly in high school, the Classics were the main bulk of the curriculum. Admittedly, I haven’t read much literature beyond the 19th Century (and the 20th Century literature I have read mainly comes from the early 20th Century). I also tend to enjoy this type of literature too; it serves as a sort of muse.

It’s not a just a tragedy, it’s a horror of sights and emotion. Sophocles really railed against the injustices of fate.

I wouldn’t say fate as it’s something that either exists or doesn’t, and nothing can be done in any event (so it would make very little sense in light of the currents of stoicism and proto-stoicism that existed in this time). I could, however, see an interpretation where he was railing against accepting a view of fate predominant in Ancient Greece. Just a thought.

Rather simplistic interpretation of the relationship between Oedipus and Jocasta, his wife/mother. There are more things in heaven and earth than are dreamt of in your philosophy.

Just out of curiosity, how would it be simplistic?

How deep should it be? These articles are not meant to be written for a ProQuest. I think the writer brought up some good points.

I have a question. When you say she becomes an everywoman, are you comparing her existence to the play, Everyman?

A really fascinating deep dive examination – thanks for sharing this great read with us.