John Waters and the Allure of Filth

A fascination with the work of John Waters is something that invites, nay necessitates, a bit of explanation. There must be some rationalization that we, as admirers, can use to vindicate ourselves from the fact that we oddly but so genuinely revel in the art of bad taste, the glorification of filth, the subversion of humanity’s collective vision of the “holy,” the “sacred,” the “divine.” Can his work even be considered art—or is it some revolution of anti-art? A sort of aggravated blister on the immaculate body of beauty? Yes, that sounds about right.

How is this fascination to be understood? Can it be simply determined that his cult audience is a pack of revolting deviants who might benefit from psychoanalysis, advised to spend long hours on a chaise lounge unearthing the darkest, dustiest corners of their repressions? I, for one, though unquestionably neurotic, have never been particularly attracted to the perverse, and have had a very strict—quasi Platonic—notion of aesthetics: i.e. the belief that art is equated with beauty, a word interchangeable with supreme moral goodness and truth. To heed this sterile, right-wing viewpoint would inevitably lead me to argue that nothing is more morally bankrupt, more pernicious (as a critic once exclaimed, much to Waters’ pleasure) than the works in question. And yet, they afford charm and delight. It would be mistaken to deny that Pink Flamingos, Multiple Maniacs, Polyester, or any film in the Waters’ treasury are not only works of art, but fantastic works of genius. If filth is not yet an acknowledged aesthetic category, it’s high time we make it one.

Waters is of course not the first artist to sing the praises of the freakishly unnatural, to play with the poetic qualities of the grotesque and taboo. He openly credits Diane Arbus and Andy Warhol as major inspirations, and it’s clear that his work runs on the same meandering tracks as Theater of the Ridiculous, the aesthetics of camp (probably the closest that his works get to an aesthetic category), and basically any movement that revolts against art-as-institution. And even though Waters isn’t mentioned in the “Cinema of Transgression Manifesto,” his art certainly meets all the criteria. Nick Zedd’s sermon of depravity could easily be mistaken for a sample of David Lochary dialogue: “We violate the command and law that we bore audiences to death…and propose to break all the taboos of our age by sinning as much as possible. There will be blood, shame, pain and ecstasy, the likes of which no one has yet imagined. None shall emerge unscathed.” In fact, if you watch enough of his films in succession, you almost can’t help but read this whole manifesto in the same zealously monotone, mockingly sanctimonious voice which underlies many of the Divine/Lochary tirades.

But Waters is special; not just anyone gets to be christened “The Pope of Trash,” “The Sultan of Sleaze,” “The Prince of Puke,” or “The King of Bad Taste.” He deserves these titles more than any artist before him, and this makes him a legend in his own outlandish right. In fact, I thought I had cleverly coined a new moniker—”The Duke of Debauchery”—but, as it turns out, there is no bottom to his vault of nicknames, no limit to his eccentric knighthood, and this name was already conceived. So how about “The Victor of Vice?” Not as fetching, but at least it’s my own.

It’s a reasonable assumption that the root of fascination and the explanation behind his distinction are one and the same. But we cannot confide in Waters to give a candid explanation. He has claimed that his films “don’t mean anything”–which might, remarkably, be true for some B-movie makers, but it is certainly not true that his work is too low, or too transcendent (whatever that would look like), to convey meaning. Waters is an artist and no artist works without substance, even if it’s exhibited in the most outrageous way. There is an element of truth in his filth.

In the Land of Camp and Irony

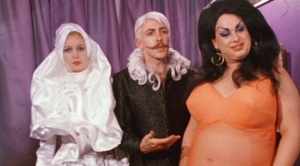

Take Pink Flamingos, Waters’ magnum opus, his most cult-celebrated film and one of the leading midnight movie classics. The plot centers on the pursuit of flamboyant sweethearts Connie and Raymond Marble, who traffic female hitchhikers and run a baby ring in their cadaverine-polluted chamber, as they compete for the title of “Filthiest Person Alive,” which, in the world of the Dreamlanders—the Waters’ troupe—is undoubtedly the most venerable achievement. The current titleholder goes to a cross-dressing, Clarabelle look-alike named Divine. Needless to say, Waters’ imagination is supremely fertile in the land of irony: the land of celestial counterculture, where to be divine is to be the saint of the underground and the fiend of the bourgeois. The land where, in the act of extreme irreverence, the murderous, incestuous, and cannibalistic drag-queen gets to proclaim “I AM GOD!”

To deal in the realm of irony already makes his work distinguishable from the contemporary B-movie industry, which in general thrives in the absurd for the sake of absurdism. And it is not even bad taste for the sake of bad taste or shock value. Waters wants to make a point. He wants to sabotage suburbia by glorifying the misfit, because—and here is the point—nothing is really more filthy than the made-to-order ‘way of life,’ with its prudish morals and its nose up the air. The theme of the film, the ambition to earn recognition as the filthiest person alive, becomes satirical if read as a comment on the extravagance of our (i.e. society as a whole’s) values of competitive worth: e.x. who is the wealthiest, the most successful, the most admired / attractive, and, perhaps among millennials like myself, the most ‘liked’ on social media. Perhaps this is really what it means to be “filthy.”

His second most popular non-mainstream film, Female Trouble—dedicated to former Manson family member Charles “Tex”Watson–deals basically with the same concept, only with more specific subjects: beauty and fame. To be beautiful is to be as grotesque looking and criminal as possible, which of course is also to be divine. Again, in the land of irony everything commonly thought hideous and shameful is paragon; the “reverse state of grace,” as Waters called it. It has occurred to me that, in a very strange way, Divine—even when she acquires a new character name, in this case Dawn Davenport–constitutes a sort of postmodern allegorical figure encompassing and enchanting all of the early films: the personification of all that is not, in any lexicon outside the language of John Waters, signified in the word divine.

So what exactly is the point of this film? Waters would probably deny that there is one; but it’s easy enough to perceive his fundamental argument at play: the rebellion against the status quo, the ludicrous lengths society is willing to go for beauty and social power.

The Aesthetic Theory of Bad Taste

Intellectual discourse on the aesthetic core of Waters’ work is surprisingly scarce. Even if he isn’t the prime mover behind the art of bad taste, he is—remember—its proud king, and his genius merits more analysis. The closest we have to a formal aesthetic theory is probably this passage from one of his autobiographies, Shock Value:

“To me, bad taste is what entertainment is all about. […] But one must remember that there is such a thing as good bad taste and bad bad taste. it’s easy to disgust someone; I could make a ninety-minute film of people getting their limbs hacked off, but this would only be bad bad taste and not very stylish or original. To understand bad taste one must have very good taste. Good bad taste can be creatively nauseating but must, at the same time, appeal to the especially twisted sense of humor, which is anything but universal.”

If Waters has read any of the classic theories of art (which, being well-read, he likely has) it was preeminently to get ideas on how best to controvert them. Even while seemingly agreeing that there is something called a “standard of taste,” or at least recognizing that there is a logic to it, the notion of reproducing anything inducing universal response is, for him, most undesirable.

But does it really take aesthetic acumen to understand the dignity of good bad taste? Can the same person who cries over Van Gogh’s sunflowers, who routinely listens to the nocturnes of Chopin, who revels in the impressive force of a Dostoevsky novel or a Bergman film, also be wild about the pure offensiveness that makes a John Waters original? Can someone who has a generally lofty sense of good taste, also have an intellectual admiration for bad taste? If I am any point of evidence, the answer is absolutely yes. And the point of defense is becoming palpable.

If John Waters is right, then it isn’t bad taste in and of itself that we enjoy; it’s the esoteric appreciation of subverting good taste, the intellectual pleasure of comically overt irony and exaggeration, the mixture of good humor and rebellion necessary to conceive a world where everything we ordinarily condemn and ostracize is heartily welcome. And because of this latter motif, it is even worth claiming that his films—despite the irony, or perhaps by virtue of it—are oddly life-affirming and heroic.

This is not to say that Waters promotes any of the debased actions his films brandish; he certainly doesn’t ask for a world without morals or a tribe of Manson-inspired delirium led by the constitution of Babs Johson: “Kill everyone now! Condone first degree murder! Advocate Cannibalism! Eat Shit! [etc., etc.].” As an audience, we have to grant the fact that the content of his work is radically out of reach of any sort of moral framework, that it wholly dwells in the realm of bad taste. But as works of art, they do at the same time attest to Waters’ unique doctrine which embraces the beauty of the bizarre, and asks that the world of parochial norms extend its view and so become more fully realized. That people will be received as they are, however different.

For those of us eccentrics, believing no one stands behind us, no one roots us on in all our strangeness: I know one man we got, and that man is John Waters.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Back in the mid 80s, when I was a college freshman at Kent State, John Waters spoke on campus, and boy, was my friend excited, after seeing him several times on Letterman (but having never seen any of his films). The night before his appearance, the school’s film society screened Pink Flamingos and we went, never having seen it before. The next night, when Waters spoke (after a screening of Polyester), my friend refused to attend. Thankfully, I did, and got my Odorama card signed. A magical evening.

LOOOOOOOOOOOOVE this man so much. Just imagine what this world would look like had Divine lived..

Having seen Pink Flamingos, Cry-Baby and Cecil … Demented is the one I remember most and enjoyed the most while watching.

I agree. It’s a great homage piece.

Great work on analyzing John Waters and his work. I especially like this: “If John Waters is right, then it isn’t bad taste in and of itself that we enjoy; it’s the esoteric appreciation of subverting good taste.” The repeated subversions and inversions of appropriate societal behaviors are indeed extremely likely appeals because, as you said, misfits can be shown in a sort of celebratory manner.

If there is one man I would kill a mother fucker to be mentored by, it would be John Waters.

To date, the only Waters films I’ve seen in a theater was A Dirty Shame at a sold-out screening in Philadelphia opening weekend. That may have been the most I’ve laughed at any film ever.

A Dirty Shame was the first one I saw in the theater and I cried laughing. The only other one I’ve been to was a more recent midnight screening of Pink Flamingos, in which PEOPLE WERE WALKING OUT IN DISGUST. How in this day & age do you not know what you’re getting into before you get to the theater? Amazing.

A national treasure.

Last week I saw “Suburban Gothic”, Richard Bates, Jr.’s follow-up to “Excision”, and it clearly wants to be a John Waters film (even Waters himself has a small role). I found it frustratingly silly, showing close-ups of feces and vomit just for the sake of it. Made me miss Waters as a director. Even his worse films – and he hasn’t made a truly terrible film so far -, feel genuinely like his work, flaws and all. I don’t think anybody could replicate that.

I, for one, would like to hear more about John Waters’ former career as a children’s-birthday-party puppeteer.

Truly original work by a great artist.

I’m very happy to say I know John! He’s such a wonderful man! If anyone does not like him they are insane!

He is such an inspiration to me. I hope I can meet him one day, I hope I can make a film he would LOVE.

One of the best movie watching experiences I’ve ever had was watching “Pink Flamingos” with a bunch of friends, which none of us had ever seen before. The trashy, filthy content definitely lends itself to communal viewing.

I watched Pink Flamingos alone on a laptop in a hotel room, which is not ideal. I took a break after the hot dog penis, and didn’t return. I’d like to watch it again in public sometime.

I pray to John Waters.

Love john waters!

Waters once said that his core audience is “minorities who don’t even get along with other members of their own minority.” I think that pretty much says it all. He has also said he’s finished making films, and we are all the sadder and poorer as a culture (“sub-” or otherwise) for it.

John Waters is a really inspiring figure because he definitely promotes the idea that you should just get out and do it if you really want to make movies. That being said, I wouldn’t want to actually see any of his stuff. Definitely not my thing.

I think Pink Flamingos would have to be the most disgusting, stupid and unique films ever … to watch that film is to have an experience like no other. It’s a masterpiece.

I agree that there is not enough discourse on John Waters as a filmmaker. The fact that his art is considered “low” should in no way diminish the messages of his movies. You did a wonderful job arguing that beauty cannot be the only aesthetic concept. You start a great discussion of whether we should appreciate an “ugly” work for its artistic representation or do we appreciate the cognitive ideas such a work may represent. Or is it both?

During my college days, I ducked into my favorite bookstore in Washington DC. A rail-thin man with a pencil thin mustache was sitting on a couch with a stack of books on a table next to him. No one would venture near him. They didn’t know who he was. I did because I had just seen Pink Flamingos at a midnight show. It was John Waters. When I passed he said “Hello”. We had a very nice chat about film in general and his book that he was promoting Shock Value.

Absolute legend.

The great thing about seeing a John Waters’ film is that you’re not just watching a movie, but actually having fun doing it. I saw Polyester in Odorama recently, and what a great time it was!

Great article! For anyone wanting further info on John Waters, Netflix has a “A-Night-With” style show called “This Filthy World.” In this, Waters discusses his influences, thought processes, etc. and is a solid/hilarious watch.

“If filth is not yet an acknowledged aesthetic category, it’s high time we make it one.”

Positively loved this entire article, as well as Pink Flamingos, the only Waters film I have yet to see. It is impossible for me to recommend this film to most that I know, who would or do see this as pure revolting, or question how I can be a passionate fan of something that depicts and makes light of things that are truly upsetting. Others could try this and do so terribly and offensively, yet when Waters does it I laugh and gasp and indulge in doing so in safety.

A good essay. I remember sitting on a barstool next to Divine at Max’s Kansas City off Union Square in New York City–friends always enjoyed hearing that.

I haven’t watched any of his movies, but I am interested now, after reading this. Nice inspection of his work.