The Lewis Carroll Problem

Charles Dodgson— better known as Lewis Carroll— is generally regarded as the father of modern children’s literature. His primary contribution to the canon of English literature, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865) and Alice Through the Looking Glass and What Alice Found There (1872), have earned a great deal of affection from the better part of ten generations of readers, many of whom maintain their love of Alice and Lewis Carroll over the course of their entire lives. Carroll’s cultural staying power is not up for debate (regardless of his relatively obscure entries, like 1889’s Sylvie and Bruno). It is Lewis Carroll himself, along with his dubious intentions as an author and as a human being, who is under scrutiny in literary and historical circles. Wonderland has held our attention for 150 years, but something about it gives us pause. Speculation on Lewis Carroll’s sexual violence toward children are one strike against him; another is the hippies who adopted his books as a metaphor for psychedelic drug use. These historical details indicate a dark figure lurking just behind the books’ fantastical window dressing. It is for this reason that many modern readers regard Carroll’s works as they might a picturesque pond with a murky underbelly, despite the story’s presupposed innocence.

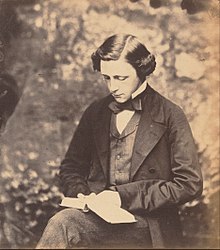

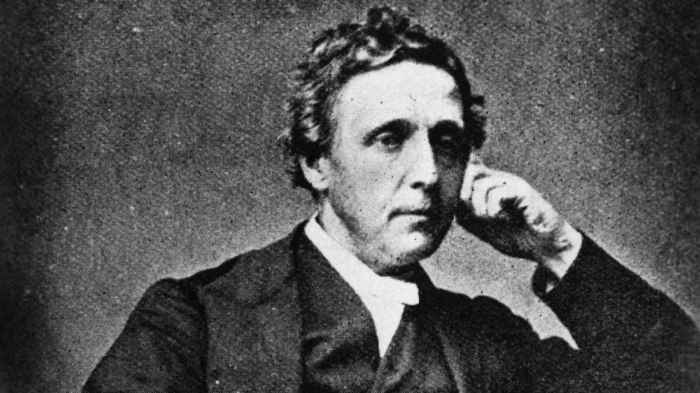

Before we begin our review of Carroll’s cultural impact, it is necessary, I believe, to review Dodgson’s personal history. Lewis Carroll aka Charles Ludwig Dodgson was born in 1832, Daresbury UK. He was noted throughout his life as timid, somewhat sickly, and “painful[ly] thin” (Wallace 172). As a child, he suffered from whooping cough (174), walked with a herky-jerky limp as an adult, and stuttered terribly when speaking. He was the third in a line of eleven Dodgson children, all of whom, with the exception of Charles himself, lived into the 20th Century (lewiscarrollresources.net). As a young man, he studied mathematics at Christ Church Oxford University and graduated with First Class Honors. In the years that followed, Dodgson would climb the academic ladder, becoming a mathematics lecturer at his alma mater (1855-1881) and later attending a “Masters of Arts” program in 1857 where he would be named Christ Church’s “Senior Student” (ibid). In 1861, he became an ordained deacon, like his father (Archdeacon Charles Dodgson) and grandfather (Captain Charles Dodgson) before him. He neglected, however, to follow in their footsteps to completion by becoming a priest.

Dodgson was noted by his peers for a number of seemingly paradoxical personality quirks. He and his biographers support the claim that he was a man of reasonable health, although he died in his early 60s after bouts with “…severe migraine attacks, synovitis (most likely osteo-arthosis), ague, eczema, boils, and cystitis, all of which were reported in his diary from age 53 until his death” (175). His peers often characterized him in a contradictory light. “Some colleagues knew him as a somewhat reclusive stammerer, but he was generally seen as a devout scholar; one dean said he was ‘pure in heart’” (Woolf); meanwhile, Martin Gardner describes him as a classist conservative who was “awed by lords and inclined to be snobbish towards inferiors.” Dodgson’s affectionate relationship with Alice, Lorina, and Edith— the daughters of Henry Liddell, Dean of Christ Church, Oxford— was only one instance of his serial “child friendships,” as he spent a great deal of time writing to and traveling with them. “Like many Victorian bachelors, he became a sort of uncle to his friends’ children, making up stories and games and taking them on short trips; the role ensured him a warm welcome in many homes” (Woolf).

On the now famous date, July 4th, 1862, Dodgson rowed himself, the Liddell sisters, and his friend and colleague Robin Duckworth along the River Isis. It was during this trip that he first formulated the story of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, which the fictional Alice’s real-life namesake urged its author to write down and publish. An early manuscript would ultimately be presented to her as a Christmas present, complete with original Carroll illustrations, prior to its official publication. The presence of Duckworth may have been a key influence of the book’s subject matter, as there are many mathematical, logical, and linguistic problems baked into Alice’s escapades; Dodgson spun this story to entertain all of his passengers, after all, and it is only natural to joke about philosophy with a fellow philosopher.

Reportedly, Dodgson was quite close with the entire Liddell family— including the sisters’ parents and brother Harry— but a rift developed between them in June 1863. “…Something happened, and Lewis Carroll was exiled from the deanery” (Kearney). It is unknown why Dodgson was ejected from the deanery or the Liddells’ personal lives. When exploring his diary for answers, Kearney and other researchers like her can only find “razor cut[s]” where specific pages (presumably pertaining to the incident) were removed, presumably by Dodgson’s nieces after his death. For five months following this apparent rift, there’s no mention of the Liddell girls in the diaries at all, until we come to the December 5th, and there’s a theatrical evening. At the very end of that day, Lewis Carrol writes: “Mrs. Liddell and the children were there, but I held aloof from them, as I have all this term” (Kearney).

The cause of Carroll’s dislocation from the Liddell family is still unknown today. Evidence— such as letters exchanged between Alice and Lorina— suggests that Carroll was meant to be courting Lorina or perhaps the Liddell family’s governess, Mary Prickett. However, like most of the finer details from Carroll’s life, the information one might scavenge is cryptic. This is only a rough sample of the facts— dry, if incomplete. Many scholars are compelled to parse the details in search of fuel for a psychoanalytic fire or to uncover the bare truth of Dodgson’s character, be it pure and bittersweet or contaminated by sexual deviance.

Wonderland is an explicit dream world populated by self-proclaimed madmen and madwomen. Insanity and the unconscious mind form the thematic backbone of Carroll’s work, and thus, he drew the attention of early 20th Century psychoanalysts as sun-cooked meat attracts flies. According to Woolf, Carroll’s popularity as a Freudian target began in the early 30’s:

[In 1933], a writer named A.M.E. Goldschmidt presented at Oxford an essay titled “Alice in Wonderland Psycho-Analysed,” in which he suggested that Dodgson was suppressing a sexual desire for Alice. (Her fall down the well, he wrote, is “the best-known symbol of coitus.”) Goldschmidt was an aspiring writer, not a psychoanalyst, and some scholars say he may have been trying to parody the 1930s vogue for Freudian ideas. Whatever his intent, unambiguously serious writers picked up the thread. (Woolf)

Woolf goes on to cite the work of Goldschmitdt’s contemporaries, Paul Schindler and Martin Grotjahn, who published more explicit remarks on Alice in Wonderland’s psychosexual content. “‘We are reasonably sure that the little girls substitute for incestuous love objects,’ wrote New York University professor Paul Schilder in 1938. The meaning of an illustration of a long-necked Alice is ‘almost too obvious for words,’ psychoanalyst Martin Grotjahn offered in 1947.” The 1990s, however, saw another boom of psychoanalytic Wonderland discourse, with “Three major biographies published in the 1990s, by Donald Thomas, Michael Bakewell and Morton Cohen…” (ibid) and the work of Richard Wallace, to which we will frequently return over the course of this essay. In The Agony of Lewis Carroll (1992), Wallace supports the theory that Dodgson was some shade of sexual deviant (sometimes by Victorian standards— a homosexual; sometimes by modern standards— a man who took sexual interest in teenagers; sometimes by the standards of both cultures— a pedophile). He relies heavily on a Freudian framework as applied to Carroll’s biography, as we can see in the following passage:

Some writers and biographers have discussed a perceived “split” in the Dodgson personality. Langford Reed takes the strongest position when he contrasts the pedantic, stammering, shy Oxford don with the humorous, childlike Lewis Carroll. There is generally a rejection of that notion. I reject it to as a clear split between Dodgson and Carroll; for as we shall see, both sides of Charles Dodgson appeared under both identities. But there most certainly was a split within the fragile Dodgson character. There was firstly the split that occurs when the damaged self unconsciously creates a false self and hides the true self within the one person. In Dodgson’s case, we have a much more serious split, that much like Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, a story written and published in the mid 1880’s. (Wallace 168)

Wallace also goes on the assert a suspicion of psychosis in Carroll’s early years and reads much of his work as autoerotic, incestuous, and homosexual allegory. His contemporary Carroll biographer, Karoline Leach, however, argues the exact opposite position:

Dodgson’s surviving letters suggest that he had a keen interest in women—and worked to circumvent the Victorian proscription of mingling between unmarried adults of the opposite sex. […] In 1999, Karoline Leach published yet another Dodgson biography, In the Shadow of the Dreamchild, in which she quoted the summary of the missing diary information and argued that her predecessors, misunderstanding the society in which Dodgson lived, had created a “Carroll myth” around his sexuality. She concluded that he was attracted to adult women (including Mrs. Liddell) after all. (Woolf)

Even more bizarre is Martha Kearney’s exploration of Carroll’s controversial photographs of naked children, particularly a “full frontal picture of a naked young teenager, a picture which no parent would have consented to” (Kearney). The photograph is attributed to Lewis Carroll and labeled “Lorina Liddell.” Kearney spends the latter twenty minutes of her BBC Two documentary, The Secret World of Lewis Carroll (2015), attempting to verify or dispel the photograph’s validity.

She brings the original image to several forensic researchers: a picture conservationist (who establishes that the photograph was taken in the Victorian period and that it was taken and developed in the way Carroll was known to take and develop his photos) and a forensic imagery analyst (who compared the nude photograph to confirmed images of Lorina Liddell and reported that “forensically speaking… there is moderate support for the contention that the girl in the photograph is Lorina as shown in the other images. As this is not a court case, I’m prepared to get off the fence and say, in my opinion, this is Lorina Liddell”). Kearney concludes that the evidence is compelling but not concrete. In contrast, Woolf writes of Dodgson’s retrospectively disquieting hobby:

Of the approximately 3,000 photographs Dodgson made in his life, just over half are of children—30 of whom are depicted nude or semi-nude. Some of his portraits—even those in which the model is clothed—might shock 2010 sensibilities, but by Victorian standards they were… well, rather conventional. Photographs of nude children sometimes appeared on postcards or birthday cards, and nude portraits—skillfully done—were praised as art studies, as they were in the work of Dodgson’s contemporary Julia Margaret Cameron. Victorians saw childhood as a state of grace; even nude photographs of children were considered pictures of innocence itself. In discussing the possibility of photographing one 8-year-old girl unclothed, Dodgson wrote to her mother: “It is a chance not to be lost, to get a few good attitudes of Annie’s lovely form and face, as by next year she may (though I much hope won’t) fancy herself too old to be a ‘daughter of Eve.’” Likewise, Dodgson secured the Liddels’ permission before taking his now-famous portrait of Alice at age 6, posing as a beggar child in a tattered off-the-shoulder dress; the family kept a hand-colored copy of it in a morocco leather-and-velvet case. (Woolf, ellipsis in original)

This may be enough to dismiss his many nude portraits of children, but it leaves the problem of the maybe-Ina nude photograph intact. The age of consent in Carroll’s time was twelve (Kearney), meaning that this image is on a bizarre cultural borderline. Today, it would be considered child pornography, but at the time, it was not an angelic artistic nude of a child; it was a naked portrait of a woman, ergo, standard issue pornography and still frowned upon if not fully exploitative. There is a distinct chance that the photograph was taken by Dodgson and that it is of Lorina, but we have no incontestable evidence in any direction. This clash of ambiguous information only adds yet more frustration and disquiet to the overall Lewis Carroll debate on all sides.

After over 150 years of cross-cultural popularity and historical inquiry, Lewis Carroll has become an illusory figure. Each person who so chooses to examine his character, works, and/or personal life is at liberty to imagine their own version of why he wrote and what he was like—theories which can conceivably be supported by extant evidence. There is no firm reason not to think of Carroll as a “child-loving saint” (Woolf) any more than there is no firm reason not to observe him as a pederast. At present, no fact left behind is quite damning nor absolvent enough to end the debate.

In two centuries, the popularity of the Alice books has never waned, and as such, its revered author has gathered a great deal of cultural lint. “Since the 1930s, biographers and scholars have questioned the nature of Dodgson’s relationship with the 10-year-old girl to whom he first told the story, and since the 1960s his work has been associated with the psychedelic wing of the countercultural movement” (Woolf). Our understanding of Lewis Carroll will always be somewhat blurred by the cultural differences between Victorian England and the 21st Century West. His contemporaries were blissfully ignorant of post-Freudian anxiety and “stranger danger”; they viewed homosexual behavior as a perversion and a crime. Today, a man behaving as Carroll did in his time would be regarded in a wildly different light, mainly because behavioral flags and their translations have changed. If a Victorian man could receive a parents’ blessing to take artistic nude photographs of their prepubescent daughter without any suggestion of squeamishness, then can it be accepted as evidence of pedophilic interests? Hard to say. Would a 21st Century Carroll still make such a request? Doubtful. If his admiration for children was truly as pure as one would hope, then a modern Carroll would shudder at the very idea; were he really a pedophile, then he would have to find a sneakier way to acquire child pornography than simply asking for it. Thus, we are left at square one again, still without any indication of whether the Alice books were informed by sexual predation, intergenerational commiseration, both, or neither. At this stage in our inquiry, we have wandered onto Rolland Barthes’s doorstep; for why do we long to understand Lewis Carroll if not to understand the beloved books he had authored?

The author still rules in manuals of literary history, in biographies of writers, in magazine interviews, and even in the awareness of literary men, anxious to unite, by their private journals, their person and their work; the image of literature to be found in contemporary culture is tyrannically centered on the author, his person, his history, his tastes, his passions; criticism still consists, most of the time, in saying that Baudelaire’s work is the failure of the man Baudelaire, Van Gogh’s work his madness, Tchaikovsky’s his vice: the explanation of the work is always sought in the man who has produced it, as if, through the more or less transparent allegory of fiction, it was always finally the voice of one and the same person, the author, which delivered his “confidence.” (Barthes 2)

When prodding into Dodgson’s personal letters and affects, we are searching for the quirk at the center of his universe: “blank” is to Carroll as madness is to Van Gogh and vice is to Tchaikovsky, etc. Whatever we fill that blank with radically changes the text. If the causal element we settle on is “pedophilia,” the most pivotal work in the canon of English speaking children’s literature suddenly becomes a twisted erotic romp in which a small child is tormented and worn down to tears for the writer’s amusement. If we select “empathy for children,” then the book is a lighter tome, a bittersweet exploration of the existential frustrations all children experience but cannot yet articulate. A radical shift towards “queerness”— gender dysphoria or homosexuality, perhaps— makes Alice’s adventures yet more Freudian and more autobiographical: the young girl Carroll was never allowed to be stumbling through a world of internal obstacles. Yet more conceptual still is “love of philosophy”: perhaps the whole thing was a screed against abstract mathematics and a vehicle for punning logic games.

The truth is, Carroll’s Authorly Quirk may be all, none, or some of these, and it wouldn’t matter quite so much if the worst-case scenario weren’t so disturbing. For example, Edgar Degas’s vehement anti-Semitism might be difficult to swallow, but it is easy to set aside when viewing his lovely paintings, as those paintings are not directly related to Jewishness or Nationalism. Carroll, however, found his muse in children, so the suggestion that his fascination was sexual rather than fatherly or fraternal rankles. If Degas’s sin was serial sexual abuse of ballerinas, it might yet destroy the beauty of Ballet Rehearsal on Stage (1874).

Naturally, this type of thing has become a topic of heated debate among Carroll fans and scholars. For example, when Leach introduced In the Shadow of the Dreamchild, “The reaction among Dodgson scholars was seismic. ‘Improbable, feebly documented…tendentious,’ thundered Donald Rackin in Victorian Studies. Geoffrey Heptonstall, in Contemporary Review, responded that the book provided ‘the whole truth’” (Woolf). There is no postulation that will universally please Carrollians without undeniable hard evidence (which is, at this stage, unlikely to be recovered). Our apprehension towards Carroll is, perhaps, more about ourselves and our own culture now than it is about preserving the sanctity of a literary classic. “Dodgson’s image currently stands… in contention… among scholars if not yet in popular culture. His image as a man of suspect sexuality ‘says more about our society and its hang-ups than it does about Dodgson himself,’ Will Brooker says. We see him through the prism of contemporary culture— one that sexualizes youth, especially female youth, even as it is repulsed by pedophilia” (Woolf).

Perhaps, the best thing to do at this stage is to practice radical acceptance: we must accept the shadow of doubt cast over Carroll’s legacy, acknowledge that both he and the “real” Alice are long dead, and appreciate the joys they have left behind. There is little percentage in clinging to any particular image of the man behind Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, much as Barthes’s Author is a figment of our “contemporary culture, [which] is tyrannically centered on the author” (Barthes 2). Our readings of the Alice books can be informed by what we know of Carroll— he was a conservative mathematician; he wrote to entertain a particular child; he was noticeably eccentric and neurotic— but we must restrain ourselves from skewing his work towards a Freudian autobiography. The Wonderland Carroll created is a place which deals in ambiguity: half-answers, careless dismissals, key information leaked out among needless details and punning stopgaps. It is difficult to pinpoint exactly what tormented Charles Dodgson/Lewis Carroll or how much of that torment figured into his writings. Wallace argues that he struggled with a rainbow of discouraged sexual urges: the pedophilic, the homosexual, and the masturbatory. Martha Kearney fears the worst and launches herself into an inquisition of Carroll’s personal affects in the hopes of finding salient evidence of anything, only to turn up frustrated and unsure. Regardless of these researchers’ potential factual accuracy or lack thereof— regardless of their deep-tissue exploration of the facts— Lewis Carroll is 120 years dead in 2018, and there is little use in batting his biography back and forth if our hope is to uncover the truth. What he has left us with is scattered biographical details, signs of some stripe of mental illness, and childhood paraphernalia tainted by trauma. Much like Alice and, most probably, Carroll himself, we have been left to suffer the terrible ambiguities of life, logic, sexuality, and childhood. Ironically, it is all that we can be sure of in Wonderland or in any other setting.

Works Cited

Barthes, Roland. “Death of the Author,” Aspen, 1967.

Degas, Edgar. Ballet Rehearsal on Stage, Musée d’Orsay Station, Paris.

Gardner, Martin. Introduction to The annotated Alice: Alice’s adventures in Wonderland & Through the looking glass, W. W. Norton & Company, 2000.

“The Dodgson Family Tree,” Lewis Carroll Resources, 2018. lewiscarrollresources.net/dodgsonfamily/.

The Secret World of Lewis Carroll. Directed by Clare Beavan, performance by Martha Kearney. BBC Two, 2015.

Wallace, Richard. The Agony of Lewis Carroll. Gemini Press, 1990.

Woolf, Jenny. “Lewis Carroll’s Shifting Reputation,” Smithsonian Magazine, 2010. www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/lewis-carrolls-shifting-reputation-9432378/.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

I think it’s a sign of a truly great work that the world and characters Carroll created continue to intrigue us 150 years on.

From what I understand Alice in Wonderland is the Schrodinger’s Cat of literature. An absurdity created to point out absurdity that developed into a massive cultural reference.

Alice in Wonderland along with his other books are very interesting when you consider the fact that they all contain loads of logical fallacies and riddles. That, and taking pictures of young girls were Lewis Carrol’s hobbies. Was he a pedophile? Perhaps. Furthermore, I do not believe he molested any children. Maybe there is a secret code to the entirety of his works that reveals the location of all the girls’ dead bodies after he is done with them.

An enjoyable article to read and another article on The Artifice I recommended to colleagues in our English Department.

I enjoyed helping with the editorial stage and I’ve enjoyed reading the article once again, now it’s been published. It was an interesting work, even though I don’t agree with the interpretations arrived at by ‘researchers’ such as Martha Kearney. Why do so many writers choose to ignore the fact that Alice Hargreaves (née Liddell) chose to name her daughter Carroll? Note the spelling – Carroll and not Carol. Would a grown woman name her daughter after a man who had had an unnatural sexual attraction towards her and/or her sisters? The deliberate choice of that particular spelling implies that the adult Alice still had respect, even a level of affection for Dodgson.

Dodgson was not a paedophile. Yes he had an interest in pre-pubescent girls (in particular), but not for the reasons so many think. For anyone who might be interested in pursuing this avenue of research – look into Dodgson’s interest in the Mystery Schools, his connection to the Theosophical Society and The Orphic Circle. Look at who else was connected to these groups. Why was the Orphic Circle so interested in pre-pubescent girls? Think laterally and not literally. There is so, so much more to discover.

He’s also from the 1800s. Most people forget that back, way back, laws were different.

If you like his poetry you should certainly check out Edward Lear. I do sometimes find myself drawing some odd parallels between him and other authors.

In my opinion there is no author quite like Carroll.

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass have been favourites of mine ever since I started reading novels. As a child I loved the sense of wonder and adventure they had. Many childhood favourite books remain favourites out of little more than nostalgia, but AAIW and TTLG have retained a charm that is not based solely on pleasant memories. For one, they are, to my mind, the perfect example of the internal logic of dreamworlds. Alice takes the inhabitants of Wonderland and the events there in her stride, though they appear very strange. Even now, well over 20 years since I first read them, I can find new and interesting things in Carroll’s Alice books; I recommend Martin Gardner’s The Annotated Alice to anybody who wants a starting point to reading beyond the adventure on the surface.

I can’t quite find the exact quote, but Charlie Broker once said something like “Saying that anything that’s so ‘out there’ has to be the result of hallucinogenic drugs is a complete disservice to the pure creativity that goes into it.” Something like that. I know I messed up the quote, since it’s been a while, but that’s the basic gist.

I’ve already started reading his stories to my daughter. Maybe I shouldn’t.

It was kind of the mindset back then to romanticize and fetishize little girls, but not in a sexual way, if that makes any sense. Carroll was like every other weird Victorian dude back then. He eventually did carry it too far by being annoying and writing little girl too many letters, so the mom cut off contact, but he most certainly was not molesting her.

Not only he was a pedo, he was the best girl-lover to ever live. Still is a model for all pedos everywhere. Basically, his entire life was dedicated to make little girls happy.

The author must be spinning in his grave. (If he’s not in Math heaven)

I think we need to just accept that this is how the story was written and theres nothing thats gong to change that but it is a wonderful story that has been in our cultures for decades.

The “Lewis Carroll was a pedo” seems to be a modern invention, rather than something that was ever raised at the time.

Considering his preoccupation with Little Girls he was almost definitely a ped.

Yes… but as for molestation there’s been no evidence of that. He was well liked by his little friends and their parents.

I wish when my kids asked me to tell a story, I could come up with something as imaginative as his work off the top of my head.

I love his writing. If you’re looking for more long fiction by Carroll you won’t find any, but Diversions and Digression (also pub. as Lewis Carroll’s Picture Book is a good selection of his other writings.

He was an absolute genius writer.

I hear Brock Turner is an excellent swimmer too.

Now I need to throw away all my Alice in Wonderland books!

If you like Carrolls work, you will also like:

– His Dark Materials by Philip Pullman.

– Coraline and a number of other works by Neil Gaiman.

Alice in wonderland has often been viewed as a political, cultural and mathematical satire. Carroll is not known to be an abuser, but a reference to drug abuse in Alice in Wonderland as a form of cultural commentary is a possibility. So while the myth about drugs has been debunked time and again, Carroll probably wasnt a madman rambling in a drug addled state, rather a professor making a cultural commentary

So Carroll was a mathematician who was also celibate. Sounds like a modern internetor.

I watched a documentary about Lewis Carrol that showed the photos. I highly doubt publishers would be willing to reprint something like that these days, the pictures are pretty creepy, I’d be concerned if it was on someone’s coffee table

I’ve not read his books yet, but I should.

For anyone who is interested in considering the image of children in photography and how we respond to such images here are two interesting news articles.

https://www.smh.com.au/entertainment/art-and-design/photo-withdrawn-after-child-prostitution-claim-20110821-1j4td.html

And an article on Australian Photographer Bill Henson who in 2008 actually had an exhibition raided and closed by police due to the contention surrounding his images of children.

https://www.abc.net.au/archives/80days/stories/2012/01/19/3415368.htm

I think this article is super interesting, I think the issue is that whenever someone creates a fantastic imagery world such as Wonderland people will always question the sanity of the person writing it. I feel in part it is because most people will never be able to understand a mind like that and the other half is jealousy. On the other hand, I agree that in order to have such a creative mind and to be able to come up with such fantasies a person must see the world in a different way and with this the person themselves must be different. Whether Carrol was any of these things will always be a question to wonder but his talent to write will unlikely ever be criticised.

The question for me is whether it is valid to judge an artwork on the basis of biographical information about the artist, or a work of philosophy on the basis of how the philosopher lived their personal life. Martin Heidegger has been criticised for joining the Nazi party in the 1930s: but not all of us completely condemn the value of his work, even Jewish philosophers like Levinas and Derrida.

So with Lewis Carroll….there are strong grounds to separate the work from the biographical individual, or to convert the discourse of his biographical existence into a figure of how to confront the artist as a concept.

Heidegger was a charlatan. He was already an antisemite before the Nazis reared their ugly heads; his language abuses are something people with only English (or French) will never fathom, it is part of a project of deliberate mystification, because how else can you uphold a claim of profundity in your utterances if you reveal your banality and intellectual incompetence in simple sentences? Totally overrated – a confidence act.

This is fascinating. I often unconsciously avoid hearing details about authors (with the exception of my favourite authors) because it makes me feel guilty if I enjoy their work and they are a shitty person. The analysis you have provided is intelligent, unbiased and thought provoking. Its really important to have these conversations even if there isn’t a definitive answer. Amazing work.

This is the singularly best article I’ve read on the subject. Incredibly well presented.

I commented on this article earlier and said that I recommended it to a colleague in our English department: That colleague enjoyed it. I retired so now they are a former colleague.

I hope you still stay in contact.

So refreshing to read this, thank you very much.

When school restarts in late August/ September, I’ll know if your article was discussed in class.

Woah, that would be an honor! I know I’m really late with this response (I’ve been inactive on here for years), but I’m on the adjunct teaching circuit now, so even the possibility of having my work discussed in a classroom means a lot to me. Do you remember if it got discussed at all?

I saw the photographs: toddlers in the nude, arranged so that the shadow is suggesting boobs. That was not ok then, that is not ok now. And consider the procedure, it requires a lot of touching to get the model in the right posture. Consider the equipment which is bulky and slow to operate, which is adding further opportunities four touching and correcting. We are talking not in terms of minutes but hours. This creep was grooming the kids.

I mean the problem here is, does artistic genius make criminal activities go away? Take Villon. Great poet, but also a murderer and thief. Where do we draw the line? In Dodgson‘s case we have a cleric teetering on the brink of child abuse and producing a literature meant to groom potential victims.