Roland Barthes: Love as a Language

The topic of love has perhaps been discussed ad nauseum but to unveil mankind’s long-running love affair with “love,” one would benefit by returning to the year 1977 and examining Roland Barthes’s A Lover’s Discourse: Fragments. Just as the original book does, this article will refer to miscellaneous elements of pop culture to discuss the facets of the lover’s experience. “Image-Repertoire” is a term Barthes uses to describe collections of images the lover cycles through and revisits each time in order to relate to the beloved. Here, “lover” means simply “one who loves,” “beloved” means “one who is loved,” and “love” is “a heightened state of being.” The exact nature of the relationship, its occupants, and its expression remain irrelevant just as the division between “lover” and “beloved” is often artificial and interchangeable.

What’s in a name?

Before one delves into its contents, it might be worth briefly examining A Lover’s Discourse: Fragments from first impressions. The term “lover” illustrates a solitary existence. He or she is the one “who loves,” but the object of that love is out of sight (though certainly not out of mind). Yet the second word of this title, “discourse,” suggests there are at least two people involved. After all, it is another word for “discussion” or “communication.” Since this discourse is in ways addressed to the reader, the “loved object” would be seem to be the reader. However, “the reader” exists as its own mysterious entity. The reader is in many ways a figment of the writer’s imagination, an absence that the writer flings his or her words at in the hopes of a reaction.

Lastly, there is the term “fragments.” “Fragments” denotes a disoriented state, perhaps to replicate the dizzying affect of love upon the lover. The word also suggests halted or interrupted communication, an impression alone rather than the knowledge of a great unknown. All those terms pooled together with their unifying and yet also disparate connotations is classic Roland Barthes. The title seems innocent and innocuous enough to slip by undetected, but it betrays mysterious implications upon further inspection.

An Ongoing Conversation

Juliet Capulet: “What’s in a name? That which we call a rose

By any other word would smell as sweet.” 1

(Shakespeare 2.2.46-7)

In her famous plea for she and Romeo to renounce their family name so that they may be together, Juliet entertains the notion that language itself is absurd. Juliet and Romeo are no more in control of the family name that was bequeathed to them than a rose is in charge of the label a collective group of humans has agreed to identify it with. However, were people to be rid of labels altogether, it would likely generate mass confusion and panic. Barthes acknowledges the importance of labels, but does not necessarily revere them either. Language cannot define reality, but language does inform us on how we can construct our visions of reality. How one chooses to shape reality for himself is indicative of the images that crowd one’s mind. The microcosm and the macrocosm feed each other.

In My Fair Lady, Professor Henry Higgins sings “I’ve grown accustomed to her face” when speaking of Eliza Doolittle. This is a matter of retreading the same patch of land over and over again. This endless repetition, though he might grow weary of it and soon despise it, he soon fears he will unable to live without. Much like the realm of dreams, love requires the lover to consistently reacquaint himself or herself with the beloved. Every meeting is the first one and love is merely another word for understanding. Just like Agatha and Zero (“A” and “Z”) of Wes Anderson’s The Grand Budapest Hotel, the bond between lover and beloved is the beginning and end of all language. In his gift of poetry to her, Zero has inscribed a dedication which contains perhaps all known synonyms in the English language that man could have ever created for the word “love” (adored, cherished, darling, etc.).

In Spike Jonze’s Her, the power of conversation is put on full-display when Theodore falls in love with his artificial intelligence personal assistant named “Samantha.” He can only fall in love with words, since this is all “Samantha” consists of. As a professional love-letter writer, Theodore should be all-too-familiar with this phenomenon. Theodore’s growing love for “Samantha” illustrates mankind’s larger love affair with words. He of all people should be wary of the power of words to capture the lonely human heart, as even the most emotive and seemingly personalized sentiments can be manufactured for precisely that reason. Yet no matter his know-how, Theodore can’t help but fall for the game he helps orchestrate to others’ disadvantage. Words remain an attempt to solidify ephemeral love, of continually building a sandcastle only to watch the ocean tides take it away time and time again.

In William Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night, Olivia falls for Viola disguised as her brother Sebastian due in part to language. Viola must act on Duke Orsino’s behalf in terms of a marriage proposal, which belies the fatal flaw in the Duke’s plan. How can Olivia fall in love with a man she has never met? Meeting does not just mean encountering each other face-to-face either. In The Spanish Princess, Prince Henry (the eventual King Henry VIII) hijacks his brother Arthur’s (who is Catherine’s true intended) correspondence. This is twofold a subterfuge of his older brother’s engagement and an illicit seduction of Catherine. Catherine may be engaged to Arthur in name, but it is Henry who has courted her without her knowledge. As with Henry, Viola of The Twelfth Night admits she “would be loath to cast away [her] speech, for, besides that it is excellently well penned, [she has] taken great pains to con it” (Shakespeare, lines 170 – 2). 2 Olivia is distinctly aware of a woman’s worth being calculated as part of the estate as any other possession would be, like a chair or a piece of shrubbery. While dressed as a man, Viola can appeal to Olivia by using the womanhood she herself possesses, seducing her twice-over as well.

Viola: “Most sweet lady -“

Olivia: “A most comfortable doctrine, and much may be said of it. Where lies your text?”

Viola: “In Orsino’s bosom.”

Olivia: “In his bosom? In what chapter of his bosom?” 3

(Shakespeare 1.5.221-5)

In their first meeting, both Olivia and Viola explicitly refer to courtship as if there were a series of contracts that must be continually renegotiated when terms and conditions change. Olivia seems well-accustomed to (and thus, perhaps bored with) the marriage proposals of Duke Orsino’s kind, and refers to them as if they were passages from the Bible. The same trusty book can be relied upon to refer to each and every Sunday. All she needs is the pastor’s direction to know which page to turn to for this week’s sermon.

This open dialogue is what gives Laurie of Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women the courage to try to reframe his own image within Jo March’s mind and convince her to love him in the way he wishes. Due to his inherent lack of control, the lover seeks to have the last word in his lover’s narrative. In Greta Gerwig’s film adaptation of Little Women, Laurie initially allows Jo the last word as a means of engendering her sympathy. His submission to her speech makes her words appear unnecessarily cruel and overdone. “[B]y the announcement of suicide,” Laurie acknowledges his futility and “becomes the stronger of the two: whereby . . . only death can can interrupt the Sentence, the Scene” (Barthes, 208).

“(i do not know what it is about you that closes

and opens; only something in me understands

the voice of your eyes is deeper than all roses)

nobody, not even the rain, has such small hands.” 5

(cummings, 17 – 20)

In The Hour, Freddie Lyons casually recites this final fragment of e.e. cummings’s poem “somewhere i have never travelled, gladly beyond” to his central love interest in the series, Bel Rowley. The “closing” and “opening” of the beloved suggests a phoenix-like flower that dies before it blooms again. It suggests love is a perennial plant and the lover echoes what the German poet Rainer Maria Rilke once said: “No feeling is final.” Like the speaker of the poem, Freddie is continually pulled back into an ongoing conversation with Bel no matter what the present moment might tell him to the contrary. They change frequently between frenemies to badgering siblings to soulmates with each added syllable. This continuous cycle and exchange provides the lover with the hope that he cannot be rendered mute forever by his beloved’s oppressive presence.

What happens when one grows tired of one’s text? The Apartment shows C.C. Baxter and Fran Kubelik trapped in these roles of those “that get took” by the “takers” (as Fran would phrase it). The author Kurt Vonnegut Jr. once suggested that one’s pretenses unconsciously inform one’s behavior and so one must careful about what “characters” one chooses to play. Fran inhabits the role of a compliant elevator operator, a woman that senior executives in the office building can quickly pinch while their wives are none the wiser. Baxter is the compliant pencil pusher, one of many men with paperwork-laden desks. His position could be filled by any other willing and eager ladder-climber.

Baxter and Kubelik are so immersed in these characters that they do not have to conceptualize the lover’s feeling of being submerged in images they feel they have not willfully chosen for themselves. They separately share a similar language filled with cracked mirrors and missing room keys. However, they also share the joint language of travels up and down a packed elevator and playing cards to pass the time. By choosing to engage more in the latter language, Baxter and Kubelik reshape the way they see themselves and, eventually, how others see them. By the end, it is Baxter and Kubelik who will be sending the customary sympathy Christmas fruitcake to the orchestrators of those failed relationships.

“The lover’s solitude is not a solitude of person (love confides, speaks, tells itself), it is a solitude of system . . . I can be understood by everyone (love comes from books, its dialect is a common one), but I can be heard (received ‘prophetically’) only by subjects who have exactly and right now the same language I have.” 7

(Barthes, 212)

In one scene from The Half Of It, Ellie Chu attempts to coach Paul Munsky on how to effectively court his crush, Aster Flores, by likening conversation to table tennis. Contrary to table tennis though, the object of “the game” of conversation is not to defeat one’s partner but to maintain the gentle tempo. The lover must keep his or her partner “in the game,” as a means of extending the courting process for as long as possible (if not indefinitely).

A Collision of Languages

Communication of love is hardly seamless. Two people could speak endlessly to each other without realizing they have each been speaking to a wall this entire time, one that simply rebounded their own words back to them. How can they effectively communicate with each other? Getting the words right could mean the difference between success and failure for the lover.

In the 2015 adaptation of Thomas Hardy’s Far from the Madding Crowd, Bathsheba Everdeen sings a folk song called “Let No Man Steal Your Thyme.” The word “thyme” takes on multiple meanings in the song. “Thyme” is the literal plant, a symbol of virginity, and a homophone for the word “time.” This exhibits love as a dangerous phenomena, one that exacts a painful price on the lover. If the singer and listener have not agreed which definition of the word “thyme” to use (or perhaps agreed to no set definition), the consequences could be quite dire. The hidden meanings of the song itself, the entanglement between literal and figurative interpretation, are rife with danger for its intended audience despite the seriousness of its intentionality. Much like Her‘s Theodore, despite her intrepid independence, Bathsheba winds up falling for what she has spent years guarding herself against. Bathsheba is falsely convinced, like most people, that she always knows exactly what she wants and how best to get it.

In Midnight in Paris, Gil has a preoccupation with the “Golden Age” of the 1920s Paris. The present’s inability to live up to the supposed beauty of a bygone age causes an underlying sense of melancholy and dissatisfaction within him. The main friction between the lover and the object of his desire here consists of what Antoine de Saint-Exupery describes as keeping the lover’s view along the horizon. Love is not simply a matter of admiring or simply liking the beloved, of being forever trapped by his or her form, but of being able to look outward in the same way. Like the speaker in Shakira’s song “Poem to a Horse,” the lover risks using his poetic words on a beloved unable to comprehend them. The lover risks wasting his precious time.

In the modern world, Gil’s fiancée Inez longs for a glamourous, Hollywood-esque lifestyle in America. Gil likes the more muted rainy days in Paris. In the 1920s, the erratic and passionate artists Pablo Picasso and Ernest Hemingway seek beautiful muses for their work in Adriana. Adriana is tired of this oppressive energy and is attracted to Gil, who is far more understated and sensitive compared to the men she’s used to getting involved with. However, modern-day Gil’s ideal time period is the 1920s and 1920s Adriana’s ideal era is the 1890s. Nobody’s love images seem to align. It’s like a game of “Telephone,” where the original meaning gets more and more mistranslated the further one goes down the line. As in the Mat Kearney song “Ships in the Night,” all these potential lover and beloved relationships go amiss because they speak past each other and never land where they intend.

In The Beatles song “She’s Leaving Home,” the narrative alternates between sympathetic perspectives of a daughter, who unceremoniously leaves the family home, and her parents, who lament her loss. The song exhibits Barthes’s notion of a tension between love as an unceremonious gift and a loan to be paid back in at least equal measure. This causes a great deal of distress for the lover, who is forced to cement his love “in an exchange economy (of sacrifice, competition, etc.),” which is made evident via physical offerings of food, money, etc. and “which stands opposed to silent expenditure” (Barthes, 77). What happens when the beloved craves the immaterial, just as the daughter in this song longs for a pleasure-filled life? Both the daughter and her parents appear to love each other in “She’s Leaving Home,” but fissures have sprouted up in their relationship without either party appearing to realize it. When methods of loving are so different to each other, it can seem to either party that there is in fact no love there at all.

Lockscreen

Though love is a literary and cinematic experience, the words and actions involved must be so heavily digested by both the lover and the beloved that it does not strike either as artificial. Both In the Mood for Love and The French Lieutenant’s Woman display the inherent conflict between what is staged and constructed using another’s words and mannerisms and what is based on natural and spontaneous feeling. Barthes asserts that “tenderness, by rights, is not exclusive hence [one] must admit that what [one] receive[s], others receive as well” (Barthes, 225). An actor who takes part in a passionate sex scene on film would not necessarily be accused of infidelity by his significant other because it is assumed that he is merely acting. The actions taking place in front of the camera lens are detached from the person bringing them to life.

The 1981 film adaptation of The French Lieutenant’s Woman frequently switches back and forth between the modern real world and the fictitious Victorian movie setting using the same actors. This is done unceremoniously, meaning the viewer likely finds the contrast jarring and perhaps irreconcilable. With Wong Kar-Wai’s In the Mood for Love, Su Li-zhen and Chow Mo-wan superficially adopt the roles of their cheating spouses as an act of subtle revenge and engage in an affair without an affair. Much like philosopher Jean Baudrillard’s “Simulacra and Simulation,” both individuals here are deeply aware of an image or symbol’s power to construct reality. An actual affair is unnecessary when they can simply “appear to” have an affair to an ever-watchful audience. However, this Image-repertoire becomes compromised when Su Li-zhen and Chow Mo-wan develop real feelings for each other “off-camera.”

These other images that threaten the lover’s reality become a source of enmity for the lover. In other cases, the rivals are not other versions of “me” but a legion of other people whom the lover must mimic if he is to have any chance with the beloved. At times, the beloved appears just as replaceable. This notion is abhorrent to the morally-conflicted lover, who believes pursuing love is only worthwhile because it is “special” and “unique.” In the Arctic Monkeys’s “Cornerstone,” the speaker sings of encountering women who look like his beloved over and over again. It is the lover’s hell-scape of hallucinatory “Ghosts of Beloveds Past.” Like uncanny valley with humanoid robots, the speaker wishes to transform each woman into the original beloved in question but is equally unsettled by his desire to do so.

“She was close, close enough to be your ghost

But my chances turned to toast

When I asked her if I could call her your name” 8

In Daphne de Maurier’s Rebecca as well as the animated series Le Portrait de Petit Cossette, potential rivals are long-dead. They exist only as images with no flesh-and-blood counterpart with which one can offer a comparison. There is less of a chance of spotting an imperfection when the rival can no longer bleed as the substitute is so apt to do. How can one possibly compete with the dead? When competing with locked images (as the dead often have), a certain sainthood has been certified and set in amber. Haruki Murakami’s Norwegian Wood entails making do with substitutes for the “real thing,” but the awareness of this causes unspeakable sorrow.

Yet this feeling of love being ephemeral and unreal is due to love’s very nature. As Barthes notes, the word “love” lacks an inherent meaning. Most feel at a loss to explain what “love” is, to find a container that encompasses its entire skin and all of its guts. Something is inevitably going to slip out and be lost in the process. The word “love” can apply to one’s spouse, one’s grandma, one’s favorite dance track, a slice of pepperoni pizza, etc. It is a placeholder word for a vast spectrum of feelings and thoughts.

“Like a child’s word, [I-love-you] enters into no social constraint; it can be sublime, solemn, trivial word, it can be erotic, pornographic word. It is a socially irresponsible word. 9

(Barthes, 148)

In this clip from the film Baby Driver, Debora remarks how with an abstract name like “Baby,” just about every song ever made in history is unintentionally directed toward him. Much like this soundtrack-motivated film, the closest approximation Barthes can make is music because “in the proffering of I-love-you, desire is neither repressed . . . nor recognized . . . but simply: released” (Barthes 149). It is a performance even without a visible audience. It is an exhale. In The Song of Bernadette, one of Sister Bernadette’s final words is “I love you” when a vision of the Virgin Mary appears before her. This “I love you” is a prayer and a declaration of worship. To everyone else in that room, Sister Bernadette is simply addressing the empty air. However, the lover hopes to address the “I love you” somewhere, even if that somewhere is an unseen God. How does the lover go about sending this “I love you” to the beloved and what does he or she experience in doing so?

Travels to a Distant Land

An Unbearable Immobility

The primal experience of the lover is that of being immobile. One is helplessly and hopelessly “struck” by love as if it were a bolt of lightning, an energizing force that is deadly in that it is too much for the body to take. Like a spider injecting venom into its quivering prey to lessen the struggle, the beloved takes hold of the lover and nails him to a single spot. Perhaps nothing illustrates this better than the character of Miss Havisham in Charles Dickens’s Great Expectations. For Miss Havisham, time has stopped at the exact moment her husband-to-be left her alone at the altar. In Tim Burton’s The Corpse Bride, Emily serves as the film’s namesake because she was seduced into a marriage and then betrayed (murdered) by the man she believed loved her. Both Miss Havisham and Emily represent the fatality of broken promises and romantic disappointments.

“I enter into the night of non-meaning; desire continues to vibrate (the darkness is transluminous), but there is nothing I want to grasp; this is the Night of non-profit, of subtle, invisible expenditure . . . sitting simply and calmly in the dark interior of love” (Barthes, 171).

These disappointments are not harmless, but create dead orbiting planets to the still-burning Sun. One feels entirely reliant on the beloved for existence, just as the Earth needs to be both near and far enough away in relation to the Sun for life to flourish. Barthes ascribes the lover the role of a planet patiently waiting to feel the Sun’s warmth, for it is nothing but a cold rock hurtling through space otherwise. If the planet is deprived of experiencing the warmth of the Sun (i.e. the lover does not feel the beloved’s love), then the environment the lover experiences remains inert. There is no activity. The air is deadly still.

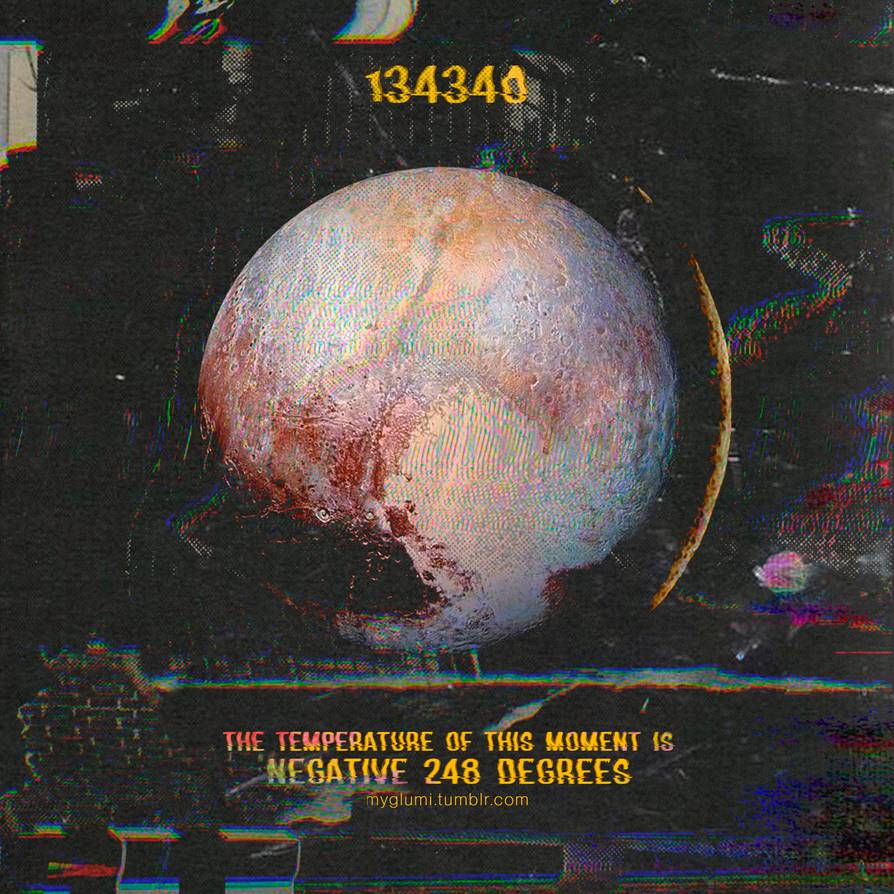

In “134340” by BTS, the name of the dwarf planet has been reduced from the dignified “Pluto” (the Roman equivalent to the god of the underworld) to the anonymous and bland number “134340.” This dwarf planet has the same position, environment, and planetary characteristics it has always possessed. However, it has now been cast aside through no fault of its own. A change in name is all it takes for the lover to be ripped away from the beloved’s warmth. The cozy familiarity of “John” becomes the coldly formal and applicable-anywhere “Mr. Smith.” A similar feeling is expressed in Florence + the Machine’s “Cosmic Love,” a song in which the lover has been plunged into darkness due to a lack of love.

As Coldplay expresses in their song “In My Place,” love is often a waiting game. As long as there is an end date to this purgatory, the heartache becomes manageable. For Barthes, the lover measures “the wealth of ingenuity . . . lavish[ed] for nothing in his favor (to yield, to conceal, not to hurt, to divert, to convince, etc.)” (Barthes, 85). It relates to the famous quote (perhaps falsely) attributed to Albert Einstein in regards to relativity. When one is in pain, the pain endured will feel eternal. However, like the humanoid robot boy of Steven Spielberg’s A.I. (Artificial Intelligence) who is granted one day to spend with his late mother, time spent with the beloved never feels enough. The neglected lover experiences a depressive state, where the future never extends beyond the present day misery.

“[W]aiting makes me more anxious than usual . . . I walk back and forth in my room: . . . everything seems inert to me, cut off, thunderstruck – like a waste planet, a Nature uninhabited by man.”

(Barthes, 87)

In The Young Victoria, Albert is feminized by his position as the Queen’s consort before he even marries Victoria. He must wait until Victoria proposes marriage to him, which would have been an unlikely position for a man to be in at the time. Even when they do eventually marry, Albert initially struggles with his new role as being forever subservient to his wife. It may be said that the beloved (love itself made incarnate) is the true king. The experience of “being in love” may make the lover feel kingly, but one is always an “an almost King.”

What exactly is the lover waiting for? For the Kings-in-waiting, a change in status in his beloved’s eyes entails a change in planetary conditions. He must patiently wait for the Sun to show her face again in the hopes the two planetary objects will grow closer and tidally-lock themselves into orbit about each other. One might think the lover would want his planet to rotate freely, so that it could be bathed in sunlight from all angles. Yet without this locked orbit, the lover will continually experience the beloved’s exit and entrance in his life. The lover wants forward-facing basking in the beloved’s heat with the cold abyss of loneliness always on his back and out of sight.

A Change in Weather

This locked orbit is an environment the lover can only ever hope to have. A change in weather, though contrary to the lover’s wish for the beloved’s unrelenting attention, provides the lover with the illusion that the intensity (and thus the amount) of love has increased. The threat of rain, sleet, or snow for the mailman to trudge through is preferred to the void of an eternally-smiling sunny day. The lover believes the intensity of withdrawal increases the potential reward of love for his patience.

“Absence becomes an active practice, a business (which keeps me from doing anything else); there is a creation of a fiction which has many roles (doubts, reproaches, desires, melancholies). To manipulate absence is to extend this interval, to delay as long as possible the moment when the other might topple sharply from absence into death.”

(Barthes, 16)

In the well-known children’s book Guess How Much I Love You? by Sam McBratney, Big Nutbrown Hare and Little Nutbrown Hare engage in an almost-duel of comparative measures of love. Does one’s love travel past the confines of the cul-de-sac, round the bend of the river, or does it fasten itself inside a N.A.S.A. space rocket and launch (fingers-crossed) toward the Swiss-cheese craters of the moon à la Georges Méliès? What does it mean when one attempts to quantify love? Other than perhaps being a form of friendly competition, it may reflect love’s ability to create alternate realities. It may be a response from the lover to the beloved’s question: “How big of a world can you create for me? Prove to me you’re my God above all other gods.”

Yet the beloved is the world-maker as far as the lover is concerned and the beloved need not be Aladdin to lead the lover to “A Whole New World.” The world appears to explode from a dull monochrome to glorious technicolor whenever the beloved is near. One is Dorothy stepping from the dull confines of Kansas into the Wonderful Land of Oz. As in Cinderella or the The Little Mermaid, the beloved promises a broader expanse to the stifling borders of one’s hometown, neighbors, and state of mind. Like Lewis Carrol’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland or Hiroyuki Morita’s The Cat Returns, the beloved is a delightful intruder. The beloved seemingly appears as a streak of sunshine peeking out from beneath a muggy, gray cloud.

In the case of someone like Tom of (500) Days of Summer, all it takes is sex with the woman of his dreams to make the world colorful and vibrant and full of possibility. The next morning Tom can be seen parading through the streets with a newfound confidence, seeing Han Solo’s reflection staring back at him from a car window. The streets erupt into a flash mob song-and-dance routine, joining him in his celebration, while Hall & Oates’s “You Make My Dreams (Come True)” blares full-blast in the background. In 2003’s Peter Pan, a kiss alone can be enough to reinvigorate one’s dull senses. Before Wendy decides to give Peter the real thing in a moment of danger, Peter thought a “kiss” was just an underwhelming thimble. In Euphoria, the enigmatic and fun-loving Jules becomes drug-addict Rue’s new drug of choice. It is quite difficult for an addict to remain in one place for any extended period of time. Her intense relationship with Jules provides her with the kaleidoscopic “highs” as well as the sepia-laden lows that come with withdrawal.

“Like a kind of melancholy mirage, the other withdraws into infinity and I wear myself out trying to get there.”

(Barthes, 112)

Like a dream, this new and once-hidden world is not constant. Like the fickle lover of Simon and Garfunkel’s “Cecilia,” who changes sexual partners when the speaker gets up to wash his face, the beloved appears to be forever in the distance. This horizon that never gets closer no matter how far you walk means rainfall might soon follow the sunshine. In Disney’s Treasure Planet, Jim Hawkins struggles with his father’s abandonment of the family. His resentment manifests itself in both the need to escape and a desperate search for a surrogate father figure. This is something Jim sees in the dynamic and adventurous but man of questionable loyalties, John Silver. Is John Silver just another escaping light, like Jim’s biological father before him? Is it possible to safeguard this precious newfound horizon?

In the film Heavenly Creatures, this other world is so fragile that any outsiders who appear to pose a threat are met with murderous outrage. Pauline Parker and Juliet Hulme are both portrayed as outcasts with vivid imaginations, able to escape the dissatisfaction and frustration in their lives by constructing more dignified alter egos. They become so entrenched in their fantasy that reality seems more unreal by comparison. For them, the fantasy of the “Fourth World” is the true world, the only world that matters and their birthright. The lover and beloved here are united against a harsh and unforgiving environment. External reality is demolished and the fantasy-building realm of the Image-Repertoire is where the lover crawls back to for protection.

In The 1975’s music video for “A Change of Heart,” it is not the outside world that poses a threat to the lover’s climate. It is the beloved. The speaker confesses that he is not sure when he was fooled by the beloved’s physical beauty into thinking she was more unique than she is. Just when he thought she was “coming across as clever,” he expresses disappointment in the seemingly insignificant and relatively minor infraction of lighting “the wrong end of a cigarette.” 11 This single moment is one of many that serve to shatter, one by one, the speaker’s illusions about the beloved. The hopelessly infatuated and heartbroken Romeo soon forgets Rosalind when he sees Juliet in William Shakespeare’s Romeo & Juliet. The beloved becomes a vacation destination, a beautiful place to visit but not to set up permanent residence.

The speaker in “A Change of Heart” seems to be excusing his own diminishing feelings by suggesting it is out of his control. One cannot stop the rain from falling down just as one can’t help falling “out of love” he seems to assert. By the end of the music video, the singer shields both himself and his beloved under an umbrella, only for her to storm (pun intended) off with it. The singer is left unprotected and alone underneath the storm cloud, even going so far as to take his hat off as well (as if to intensify his feelings of sadness). In this case, the amount of love is dictated by whim. Feelings come and go. Excitement eventually leads to boredom and back around again. The feelings of the two involved are entirely dependent on the atmosphere. Without the right weather conditions, the baseball game of love will just have to be postponed (in the case of “A Change of Heart,” probably indefinitely).

As Louis Armstrong sings in “La Vie En Rose,” the world looks more beautiful than usual when one is in love. When one falls out of love, the beloved looks like the grime-ridden reality of London in Lily Allen’s music video for “LDN.” In “A Lovely Night” from the La La Land movie soundtrack, the dueling speakers suggest a beautiful atmosphere is clearly wasted on two people who have absolutely no romantic feelings for each other. The lover’s internal state is responsible for the vividness of the external environment. However, the reverse is also true. The right lighting and the right soundtrack, as the film Liberal Arts suggests, contribute to one’s overall interior feelings of elation. Sweeping orchestral strings might induce relaxation and a lightness of being. Punk rock might produce an angrily forlorn lover. A disco strut might enforce carefree confidence.

Woody Allen’s Midnight in Paris tests this theory by giving its characters the textbook example of a supposedly romantic atmosphere: Paris, France. Gil’s major love interests in the film are both French, meaning the atmosphere likely to seduce a fresh-eyed and easily impressed tourist is an everyday backdrop for them. Gil also has a fondness for the rain. In Midnight in Paris, rain is often presented as an unexpected occurrence, a spontaneous downpour that catches the lover off-guard. This impromptu moment not only provides the chance of seeing rainbows, but it gives the lover evidence of who runs for cover and who is willing to walk in the rain with them. The woman best suited to Gil’s Image-Repertoire, Gabrielle, sees the romantic atmosphere as an album experience as opposed to choosing the right “single” of the moment. To her, rain is not simply a temporary disturbance to be avoided when possible, but an opportunity to see the beloved more clearly. It is a chance for rebirth, to get the conversation between lover and beloved started anew. Water is a metaphor for life after all.

The beauty of Paris in the rain for both Gil and Gabrielle is similar to their joint affinity for Paris in the 1920s. Artists flocked to Paris in the 1920s and it flourished as a hotspot for creativity and free-expression. When it rains, it enhances the beauty of the city just the same. The streetlights shimmer in sidewalk puddles, images are doubled or displaced by refraction, or the dimensions of nearby buildings are distorted to cartoonish proportions. Mimicking the power of the beloved on the lover’s mind, water can play delightful optical illusions. By the end of the film, both Gil and Gabrielle are able to enjoy these distortions because they already recognize them for what they are. They can indulge in nostalgia without getting lost in the past.

“Reflection is certainly permitted, but since this is immediately absorbed in the mulling over of images, it never turns into reflexivity . . . I cannot hope to seize the concept of [love] except ‘by the tail'”

(Barthes, 59)

However, the lover cannot have an entirely out-of-body experience and observe love in an objective way. Much like the durability of the lover’s Image-Repertoire, water molecules have a tendency to cling to one another. They will join together to form round droplets, bound tightly together until the pressure becomes too great and the bubble bursts. An outside force comes seemingly out of nowhere to jolt the lover back into his own body, like a still frame abruptly dying as a brown autumn leaf in the middle of the movie reel projection. As Barthes says, the lover can only reflect on love through the absorption of images the beloved produces for him. He never has the opportunity step back and self-consciously say “this is only a film” because he is himself the projection machine.

Does this mean perhaps rain (the downpour of funhouse mirror images of the beloved) is something to avoid getting overly-saturated by? The periodic rainy season shown in The Garden of Words provides Yukari Yukino and Takao Akizuki the opportunity to shelter in close proximity in a gazebo. These two are locked into an intimacy by the excuse of “bad weather.” Here, a rainy day is not an alternative type of weather to walk through. Contrary to pressing the “Skip” button, in favor of changing the setting for a more romantic one, rain provides the lover and beloved a delightful “pause” option. This is an insulated, dry-weather place where the distortional affects of rain cannot be felt. To view the beloved’s alternative world with enhanced clarity, it has to be enjoyed in short, intermittent bursts. It has the scope of the underside of an umbrella. Stray too far from the protective canopy and the lover risks getting drenched, turning blind again. As Jake Bugg plaintively sings in “When the Storm Passes Away,” the threat is the beloved moving out from under the umbrella as soon as he or she sees sunlight streaming in again.

Yukari Yukino:

“A faint clap of thunder

Clouded skies

Perhaps rain will come

If so, will you stay with me?

Takao Akizuki:

“A faint clap of thunder

Even if rain comes not

I will stay here

Together with you.” 12

The deceptiveness of the beloved is that he or she is both too close and always out of reach. Like falling raindrops, the romantic soundtrack the beloved provides for the lover can be felt but cannot be held in the lover’s hands. As The Beatles capture in the song “Here, There, and Everywhere,” the beloved is everywhere at once. This is because the lover’s world (the “Image-Repertoire”) is only in his mind, which has been saturated with images of the beloved. Everything the lover casts his eyes upon is colored by the beloved’s presence and it cannot be helped. The beloved ensures the lover’s rose-tinted glasses are in fact barely noticeable contact lenses.

Approaching the Abyss

“My fingers danced and swayed in the breeze

The change in the wind took you down to your knees

I got the good side of you

Sent it out into the blue” 13

Sometimes it is not as simple as a matter of weather forecasts. Sometimes the entire climate itself is intolerable. Sometimes it seems as though the beloved leads the lover to a precipice, like a siren luring sailors to crash their ships against the rocks. In his song “The Good Side,” Troye Sivan describes a situation in which the lover and beloved do not walk away with equal parts intact. As the beloved, the speaker expresses remorse at being able to leave in a better condition than the lover is able to. The lover here is approaching the abyss, a pit in which one cannot easily climb out. How is the beloved able to wreak such havoc on the lover, without necessarily intending to?

“The map of these exquisite points is known to me alone, and it is according to them that I make my way, avoiding or seeking this or that . . . I should like this map of moral acupuncture to be distributed preventively to my new acquaintances (who, moreover, could also utilize it to make me suffer more.”

(Barthes, 95)

According to Barthes, the lover is a road map of certain pressure points the beloved is able to exploit whenever he or she likes. The lover could be a receiver of acupuncture or a Voodoo doll, depending on the beloved’s mood. In Aurora’s “I Went Too Far” music video, the singer plaintively prostrates herself, begging and crying out for love. She does so while being simultaneously exposed to the brutal elements of rain and wind, visibly trembling from the frigid cold. The singer languishes while exposed to the unsympathetic elements, as if saying “Look at how I suffer for you!” to the beloved.

“. . . the prison cell

where her husband sits staring at the moon

until he’s convinced it’s the last wafer

god refused him, let it hit his jaw like a kiss

we’ve forgotten how to give one another, hissing” 14

(Vuong, lines 24 – 8).

In this excerpt from Ocean Vuong’s poem “Self Portrait as Exit Wounds,” the body constitutes of the violence done to it. The lovers asks to be wounded, but only by the beloved and only because he allows it. If the kiss doesn’t land where it ought, it hisses past like a bullet grazing against the skin and out into the open air. As Barthes notes, if the lover feels the beloved “suffers without [the lover] being the cause of his suffering, it is because [the lover] doesn’t count for him” (Barthes, 57). Violence, the reality of body against body, is a reminder of the lover’s frailty against forces that conspire against his wish for steadiness and sturdiness in love.

This brush with death inspires one to live more fully. Harold of Harold and Maude frequently expresses a morbid fascination with death. It is heightened to such a level that it becomes darkly comedic. He drives around in a hearse, likes to attend funerals, and stages suicides in front of his mother whenever possible (whether or not she’ll bother to look up is another matter). Harold is a young man from a well-to-do background with a controlling but emotionally-removed mother. Maude, a Holocaust survivor, is an elderly woman who openly celebrates life because there was once a serious attempt to steal it away from her.

In one scene, Harold tells Maude how each staged suicide attempt is a way of recreating his first near-death experience, one which was not of his own making. It was at that moment in which his mother displayed her one and only public display of despair at the prospect of her son’s death, though the genuineness of her despair is left achingly unclear for him. Harold has been stuck and “muffled in an inert space” where his “language is not, strictly speaking, a discard but rather an ‘overstock’: what is not consumed in the moment (in the movement) and is therefore remaindered” (Barthes, 167-8).

Despite appearances, Barthes might argue (as well as Maude) that Harold is wholly unserious about suicide. He regards death as “an easy idea, a kind of rapid algebra” which is “grant[ed] . . . no substantial consistency” (Barthes, 218). Harold is in desperate want of a public display of care, a sign that someone would mind if he decided to leave the Earth for good (Barthes, 214). His staged suicides are a way of taking ownership of things left outside his control, something Maude replicates when she decides to overdose on pills for her eightieth birthday party (without Harold’s knowledge). This spontaneous decision on her part is perhaps a way of challenging Harold to accept spontaneous, off-script happenstances. Love, a matter of publicity, never suffers entirely in silence. One approaches the abyss so as to be pulled back.

Originality and the Unutterable

Relying on/Rejecting Clichés

Even though the lover dislikes existing in silence, the experience of love is often described as being unutterable. One relies hopelessly on clichés in attempts to describe it, turns of phrase which may have once been shocking and inspired but now barely elicit a shrug. One may roll one’s eyes or let out a groan of irritation, but many also can’t help falling for clichés over and over again. To help navigate the pitfalls of language, clichés intervene like finding the perfect Hallmark thank you note. They are tried and true. No different than a can of Coke to bring a smile or Apple’s latest iPhone, a cliché is a trusted product. Countless people before the lover have already instilled their faith in its success rate. Clichés are a brand one can trust.

“[D]ependency . . . in all its purity, . . . must burst forth in the most trivial circumstances and become inadmissible by dint of cowardice.”

(Barthes, 82)

However, the power of clichés require a joint effort at deception. If the beloved is made aware and not willing to go along with packaged romantic gestures, the lover’s attempts fall flat and he risks exile. A Face in the Crowd tackles this with the character of Larry “Lonesome” Rhodes. A former petty criminal, he is able to charm millions of people across the nation when he is given the opportunity to perform on a radio broadcast. Lonesome Rhodes is equal parts magnetic storyteller and incorrigible, narcissistic rogue. His personality is a double-edged sword, what is both responsible for his quick rise to fame and what is responsible for his equally-quick plummet to nowheresville. He commands a large portion of public opinion because they place their trust in him but he also derides them when he thinks no one is listening. By the end of the film, it becomes achingly clear to the audience that Lonesome Rhodes has not acutely learned Barthes’s understanding of the lover’s dependency. Rhodes wrongly assumes his power and ability to manipulate make him the almighty Beloved who can wreak havoc on the lover at will, but he is actually the desperate lover gesticulating for a bit of attention.

In a more comical depiction of humanity’s love affair with words, one need look no further than a sketch on The Carol Burnett Show with Alan Alda as a guest. In “Morton of the Movies,” Alan Alda plays a shy man on a date with Carol Burnett’s character. Each time after being overcome with desire for this “leading man’s” charm, Burnett soon witnesses the exact same line of dialogue Alda used on TV. This scenario suggests one needn’t necessarily be Clark Gable or Ryan Gosling. One need only act like him. This acting here consists in delivering the right line in the right way. When Burnett’s character confronts him about his fabrications, he resorts to yet other movie line as a means of apology in lieu of a genuine acknowledgment of his deception. It is framed as a comedic hopeless compulsion on his part. Both Burnett’s character and the audience realize that Alda’s character borrows everything from movies, whether it be a pick-up line or an apology or anything else.

William Shakespeare’s “Sonnet 130,” believed to be inspired by and dedicated to the mysterious “Dark Lady,” attempts a rejection of traditional romantic forms of poetry. No more pale, virginal beauties with golden-flecked tresses and blushing, apple-red cheeks. “Sonnet 130” is hardly flattering. One might think it the Shakespearean version of a diss. With the “black wires [that] grow on her head,” the speaker tells readers how “breath . . . from [his] mistress reeks” (Shakespeare 4, 8). 16 If this were a Tinder profile description, one would be hard-pressed to find any swipe-rights. And no woman, however little vanity she may possess, would relish the idea of being described in such disparaging terms. As admirable a break from convention as this may be, the speaker takes an obvious gamble. Will such a confident posturing of being unimpressed by his beloved’s looks serve to intrigue? Or will it merely serve as a distasteful insult, the kind of which show the lover has trespassed into the land of no return?

Perhaps one of the most dramatic and tragic consequences of putting sole faith in words plays out in King Lear. The daughter who loves King Lear best finds herself unable to declare so, which casts her out of her father’s favor and into the clutches of her scheming sisters Reagan and Goneril. Cordelia’s sisters have little trouble declaring their love for their father in hackneyed terms of him being “dearer than eyesight, space, and liberty” or finding themselves “an enemy to all other joys” (Shakespeare 62, 80). 17 Cordelia remains silent through all of these attempts to stroke his ego for personal advantage. It is only when she is pressed by her father into making a grand declaration that she decides to simply say she loves her father “according to [her] bond, no more nor less” (Shakespeare, 102). 18 Cordelia begins the play as King Lear’s favorite daughter by default, but it takes only a moment for her innate charms to dull in her father’s eyes and for her to be exiled her from her father’s affections. Cordelia refuses to submit to clichés, dangerously attractive words that perhaps make one place faith in the shadows of real things. But this move comes at a cost.

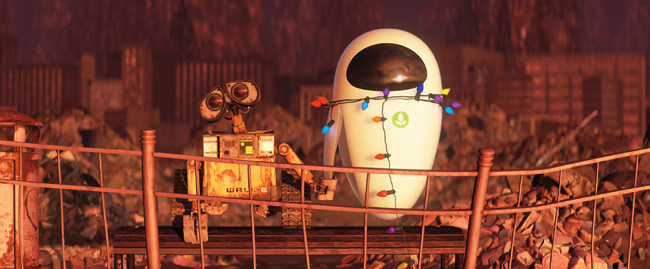

Making Contact

If clichés are mere shadows, how does the lover make contact with the beloved? In Wall-E, the movie’s namesake robot educates himself. He is particularly fond of the musical Hello Dolly, which he uses to inform himself about the specifics of human behavior. As he is seemingly the only remnant of operational humanity left on Earth (aside from a persistent cockroach), Wall-E has no outlet with which to “give” these romantic gestures to anyone or anything. He simply lets them out, releasing them into the air like an exhale. Alone in his room, it’s an almost self-soothing gesture. It perhaps mimics the way an inexperienced youth might try out “nice to meet you” lines in front of a mirror or perfect the art of kissing with an ever-patient and ever-reliable pillow. Wall-E appears curious about this human mind that created him, but of which there is no real-world application or understanding.

When Eve shows up on Earth, Wall-E thinks he has finally found his chance. Like two kids on a playdate, Wall-E is eager to show his new friend his collection of toys and memorabilia. By trying to impress the beloved in this manner, the lover is essentially trying to make contact by offering up little portions of himself as an entreaty for the beloved to reciprocate. With each successive knick-knack, Wall-E announces “here I am.” Treatment of said objects is an experiment that is indicative of how the beloved might treat the lover. Eve does not have the same relationship to man-made creations such as Rubik’s Cubes or egg-beaters as Wall-E does. Though evidently curious about these confounding items, she unintentionally breaks or misunderstands whatever Wall-E shows her. Wall-E mistakenly thinks simply showing her what he loves will make her understand automatically. He tries to abdicate the lover’s responsibility to objects to carry the conversation forward. However, such a tactic only has a chance of succeeding when the beloved can correctly interpret them as surrogates for the lover.

The opportunity for practical execution of these methods of socialization first arrives when Eve is a passive participant. She becomes dormant after her systems detect the plants she’s been searching for and during this period, Wall-E looks after her. He protects her from the rain, accessorizes her look with a string of Christmas lightbulbs, and they watch the sunset together (well at least, he does) as though they were dating. Is all of this merely the execution of clichés? Wall-E, a robot mimicking human behavior, seems no different from the lover who may parrot romantic lines in favor of a desired result from the beloved. This scene essentially illustrates a repetition of what Wall-E routinely did alone, before Eve’s arrival. In this case, the beloved is both a required participant and an after-thought to the lover’s romantic gestures that take center-stage.

Perhaps the level of artificiality involved depends on how well the lover has absorbed the lessons provided. How puréed is the meal to be digested? When a meal resembles the living organisms killed to make it, the eater is reminded of the labor and sacrifice involved. Food does not appear out of thin air. If the bones protrude from the soup and the sinews show, the greater the chance of revulsion from the consumer. Despite physical appearance, Wall-E’s humanoid nature is something he’s adopted for himself. His major glitch in the film is when he suddenly starts behaving “like a robot,” when his internal being is too well-aligned with his exterior façade. Love has no obvious utility, especially in robots. A robot’s job is consistency, of gaining assurances by following the same patterns without the messiness of new data inputs.

Subsequent intimacy between these two robots in Wall-E is often conveyed with the simple iteration of each other’s names (just like “I love you” has no inherent meaning) and “kisses” conveyed as static shocks of electricity in the air between them. Though romantics are familiar with love being ascribed the quality of electricity, visible jolts of electricity in robots are often used to convey glitches. It should not be visible because it would be a sign of something gone wrong. Electricity is wild and untamed, but illustrates contact between lover and beloved. If he does not wish to incinerate himself on the spot the beloved has tacked him to, the lover must serve as a conduit for which the beloved’s energy can channel through him before being released. Perhaps inhabiting the space between being unaware of one’s reiteration of clichés and consciously trying to stop the flood of incoming voices whenever they try to intervene and interrupt attempts at “original thought” is where the lover is at his or her truest state.

“I cannot make speeches. If I loved you less, I might be able to talk about it more.” 20

From “Emma”, 2020 film adaptation

Touch intercedes where words fail by mimicking the muteness of intense feelings. Jane Austen’s Emma Woodhouse is a character prone to constructing matches between people, like a master puppeteer, as opposed to self-reflection. Mr. George Knightley avoids flattery for flattery’s sake and is perhaps more concerned with mastering himself than others. When Emma is vain, he tells her so. When she is unkind, he tells her as much as well. Since words are likely to cause sparring matches between them, touch must supplant it. It is the only language they can agree upon. Since relations between the sexes in Emma involves far more rules of decorum and issues of civility, touch is conceivably more potent than the casualness of modern day counterparts as well.

The 2020 film adaptation of Emma exhibits this in a dancing scene between Emma and Mr. Knightley, where they are the only pair without gloves on, driving the sexual tension between them. The slightest hint of physical intimacy is charged because of its rarity and its indiscretion. Mr. Knightley even manages to touch the small of her back as well. For Barthes, the individuals in this scene are bursting at the seams with inexpressible meaning for which “there is no acting out: no propulsion, perhaps even no pleasure – nothing but signs, a frenzied activity of language” (Barthes, 68). Touch has a startling sameness to it, a universality that zips at light-speed between regional dialects and assures the lover is left dumbfounded in how to properly respond to what’s being asked of him. Contrary to the lover’s wish to gesticulate and perform, an act which aligns better with words, there is no release via physical contact. If Emma and Mr. Knightley are forced to engage in touch as opposed to speech, the encounters between them are like repeatedly shaking a carbonated drink without unscrewing the bottle cap to relieve the pressure.

What happens when touch is the lover’s only option as a means of expression? In both The Miracle Worker and Marie’s Story, a blind and deaf girl is closed off to the world until a teacher comes into their lives and recognizes how to communicate and engage with them. In both films, the girl is surrounded by well-meaning family members who are overwhelmed by her needs and thus cave in to every little demand. She becomes a stray animal, mangy with a ravenous appetite and one who bristles whenever this energy is contained by hair brushes, form-fitting dresses, or eating utensils placed in her hands. Touch alone only adds an extra layer of language for the lover to discern the meaning. Like absorbed electricity, these girls only consume what’s given with no idea of “relationship.” They lack the lover’s outlet of performing love as an act. In The Miracle Worker, when Helen Keller makes a breakthrough in her lessons with Anne Sullivan and sees the connection between hand signs and the objects they represent, she shares an emotional moment with her grateful parents. However, Helen’s focus of deep gratitude (a potential prerequisite for love) quickly shifts from her mother to the teacher responsible for giving her this newfound and efficient language with which to interact with the world.

Both films illustrate the strong connection between love and learning. Learning always requires a relationship via the interaction of dominant and submissive energies. There is “the one who knows” and “the one who wishes to know,” echoing the lover’s wish to understand and therefore navigate the beloved. The effects of touch-deprivation is obvious in infancy, where the child’s ability to rely on his or her mother’s protection correlates with levels of anxiety, strength of immunity, and long-term physical development. As Michelangelo’s famous fresco painting “The Creation of Adam” shows, touch is imbued with life-building forces and is an act of remembrance. Demonstrating one’s physical presence to another through touch ensures bonds of trust and generosity by implicitly saying: “I am here and recognize you are also here with me.”

Physical contact reminds Helen Keller and Marie Heurtin that they are living beings, capable of complex thoughts and emotions, and that they are meant for more than just stuffing their mouths with sweets and smashing plates in fits of rage. Their relationships with teachers who understand them allows them to emerge from the darkness into a world of light and language and meaning, both figurately and literally. When Bruno and Schmuel clasp hands and won’t let go in the gas chamber (an environment they are too young and innocent to realize they are now trapped in) in The Boy in the Striped Pajamas, it is a solemn vow not to abandon each other when faced with perplexing circumstances.

Touch is also potent in the world of The Artist. Shot as a silent film about the transition between silent films and the introduction of sound, the relationship between George Valentin and Peppy Miller is conducted with minimal dialogue (which is shown only through intertitles and never heard by the audience) and touch must take the reins instead. The film accurately illustrates the lover’s apprehension of the external world of speech. Like the “talkies” are to George, the societal discourse of love is loud and disorienting and appears to rob the lover of his own distinct voice (which he is in desperate need of in the presence of the beloved). When repeatedly shooting the dancing scene with which Peppy has a small role, it becomes more and more difficult to film as the real-life intimacy between George and Peppy makes itself apparent.

“Every contact, for the lover, raises the question of an answer: the skin is asked to reply.”

(Barthes, 67)

When one cannot touch the beloved, objects will have to suffice. In one particular clip in The Artist, the starstruck ingénue, new to Hollywood, enters movie star George Valentin’s dressing room. While there, she enacts a romantic encounter with him by using his suit on the hanger as a prop and a substitute for the man himself. She slips her arm through one of the sleeves and holds her own body close, smelling the scent of him on the fabric. Peppy’s actions not only exhibit the desire for autonomy in the romantic encounter, where she is not dependent on the beloved’s reciprocity, but also the chance to merge identities. When she plays both the tall, dark, and handsome stranger and the young and beautiful maiden caught in his embrace, she is both “lover” and “beloved” with not a line of distinction made between the two.

Objects crafted for the lover and the beloved may also be pacts, a physical manifestation of an invisible bond between two people. A written legal document as sign of a contract is maybe too clinical and removed from the intense emotionality a lover would wish to partake in. Moved and overcome by her beauty, Gimli the dwarf of The Lord of the Rings is happy to be simply in the beautiful elf Galadriel’s ethereal presence. However, when pressed further, Gimli humbly asks for a single strand of her hair (if she is so moved as to bequeath it to him). Perhaps touched by his courteousness and gentility, Gimli is graced with three strands of Galadriel’s hair as a parting gift. It is not just a token of admiration, but a sign of respect between elves and dwarves. This illustrates declarative love within the public sphere, but what about the lover’s preferred state of the private sphere?

In the world of Lisa See’s Snow Flower and the Secret Fan, traditional marriage between man and wife is for economic and reproductive purposes only. A laotong (“old sames”) relationship, a strong sisterly pact, is able to supply the demand for an emotional support system of a fellow woman in a similar position, something the husband would be unable to satisfy. Lily and Snow Flower exchange letters to each other on fans using their own secret language. Hand fans here are both a substitute for traditional letter-writing and the construction of a barrier against the hostile outside world. Despite being aesthetically decorative, hand fans are protective accessories that partially shield both the beloved’s face and time wasted by unwanted advances. In the western tradition, hand fans could be like air-traffic control signals, displaying various levels of interest depending on how the beloved held the fan and how much of the face was visible to the lover. For Lily and Snow Flower, these hand fans join the realms of touch (fans being an extension of the hand) and the written word (via the secret messages they contain).

“The quality of the gold is poor. The paper is as thin and transparent as an insect wing. See how the sun shines through it? We need something that will show for all time the precious nature and durability of our relationship.” 23

(See, 50)

When they initially create the relationship pact, Snow Flower suggests the the material used to write the promise is just as important as the promise itself. If the parchment is thin, transparent, and easily ripped, the promise might easily wither away as well. If the lover believes the bond with the beloved is forever, shouldn’t the material it’s constructed from be similarly indestructible . . . as if from a diamond, perhaps? The written contract is not just a symbol of the promise. It is the promise itself.

In a passage from Anne of Green Gables by L.M. Montgomery, Anne Shirley is threatened with being parted from her kindred spirit and bosom friend, Diana Barry, after they get in trouble. In an encounter unknown to and forbidden by their respective guardians, Anne and Diana meet outside. They soon declare their eternal devotion to each other, a pledge which culminates in Anne keeping a lock of her friend’s hair to seal the pact.

“Diana gave me a lock of her hair and I am going to sew it up in a little bag and wear it around my neck all my life. Please see that it is buried with me, for I don’t believe I’ll live very long.” 25

(Montgomery, 132 – 3)

For the intensely romantic (and at times overly-dramatic) Anne Shirley, this memento of her friend is no mere trifle. Though invigorated by this friendship, Anne fears she will die without Diana. An object, though comforting and soothing, is a hopelessly insufficient substitute. In fact, it can be a painful reminder of the beloved’s absence. Anne sets up a grim and guilt-inducing scene for the perpetrators of their separation: This lock of her dear friend’s hair will be the only companion for Anne’s lonely corpse when she is left six-feet underground.

If the lover always lies in waiting, then the lover is also an object. Barthes describes the lover as being always “at hand, in expectation . . . in suspense – like a package in some forgotten corner of a railway station” (Barthes, 13). The lover cannot move unless the beloved gazes upon him or picks him up off the ground and animates him into being. The lover must relate to other objects, other inanimate things who the beloved might casually brush past and animate before discarding them and leaving them wanting. Unlike the vibrant people of the world, only objects may have a sense of what the lover’s state feels like.

Barthes suggests clothing is one of the most intimate objects there is for the “lover” and “beloved” relationship. Clothing contains scent and texture and its nearness to the beloved is enviable to the lover. In the final scene of Brokeback Mountain, Ennis privately mourns Jack’s death by going through his clothes and clinging to the only things left of the man he loved. For Barthes, it is also a crime scene in which “there were always the slaughtered, embalmed, varnished body, prettified in the manner of the victim . . . embellish[ed] that which, by desire, will be spoiled” (Barthes, 127). In a romantic-sexual encounter, the woman beautifies herself only for clothing to be quickly ripped off by the man wishing to conquer her.

Taylor Swift assigns herself the role of the discarded item of clothing as the narrator in “Cardigan.” The narrator alternates between the idea of a cardigan as being an almost nostalgic source of comfort to being something easily forgotten. She is not unlike the Velveteen Rabbit whose “realness” depends on the amount of love poured into him or the toys left behind in the Toy Story franchise after the children have either grown up and forgotten them or accidentally lost them. In The Young Victoria, Queen Victoria’s style of mourning for her late husband, the Prince Consort Albert, is a rebuttal of an earlier scene that showed Albert’s dismissal of keeping unnecessary personal mementos post-mortem. When he is alive, Albert puts a stop to a tradition of setting the table for a long-dead King. An empty seat could never enjoy the lavish bounty of food laid out before it. However, when Albert passes away, Victoria wears black clothing long after the respectable mourning period and lays out his clothes everyday (though he obviously can no longer make use of them).

It doesn’t matter what you do . . . so long as you change something from the way it was before you touched it into something that’s like you after you take your hands away. The difference between the man who cuts lawns and a real gardener is in the touching . . . the lawn-cutter might just as well not have been there at all; the gardener will be there a lifetime.” 26

(Bradbury, 156 – 7)

This passage from Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451 speaks of the importance on the beloved’s touch, the impact of which continues even in death. The Little Prince initially takes this “reap what you sow” garden analogy quite literally. In The Little Prince, the book’s namesake is able to grow a rose on his home planet, an asteroid called B 612. He takes great care to look after her, despite her increasing demands. He is disheartened to learn during his travels that she is but a common rose (as commonly found on Earth as she is rare on asteroid B 612). However he soon learns that it is his love for her that makes her special because she is “his” rose. The lover’s guardianship (perhaps as opposed to ownership), even in the temporal sense, is what lends meaning to the beloved.

Pushing Daisies challenges the notion of making contact between lover and beloved to the extreme. It pushes the lover’s connection to the beloved through objects from beyond the grave and into the afterlife. Ned can revive corpses with the touch of his hand and render them dead again with another touch. The trick only works once so Ned must be careful in regard to touch. When he revives his deceased childhood sweetheart, Charlotte (known by her nickname “Chuck”), it is the one and only time he can touch her if he wants her to remain alive.

The two devise all sorts of loopholes with which to contrive intimacy with each other. Beekeepers’ suits for dancing, plastic wrap for kissing, and winter gloves for hand-holding. Not only can the lover only conduct a relationship with the beloved through objects, but this relationship is an active one. Traditionally speaking, objects are only potent because they easily conjure the lover’s use of his Image-Repertoire through the aid of physically-bound memory. Objects say: “Here is a shadow of your beloved. And here. And here too.” In Pushing Daisies, objects are pushed into the jarring realm of the present tense as a vehicle for understanding between lover and beloved. Chuck is not some distant memory locked away in objects for Ned to interact with at his own pace, from time to time. Ned proves his love to her in an active sense by limiting his contact with her as only being possible through objects, despite his ability to physically reach out and touch her in the here-and-now. Objects are not just mere symbols here, but all-important evidence of the lover’s sincerity of intention towards the beloved.

Proof of Love

Empty Words?

Destructive touch is at times preferred to words, which in their immateriality and lack of visible location suggest the beloved cannot wholeheartedly trust them. It simply isn’t enough to claim to love because as Tessa Violet says in “Words Ain’t Enough,” they can be merely pleasant placeholders that only serve to soothe the lover’s lingering anxieties. Gabrielle Aplin’s “Sweet Nothing” subverts the romantic phrase. When a lover whispers “sweet nothings,” it is usually taken in an entirely positive light. However, Aplin uses the phrase to express disappointment with flattering, but ultimately empty, compliments. Barthes’s acknowledges the failures of language as well, especially as far as the lover is concerned.

However, it is not enough to simply dismiss the importance of compliments and flattery and other words used to signal admiration. In Enchanted, Princess Giselle makes an impassioned case for the importance of “sweet nothings” on Robert’s behalf. Robert is bit more cynical and pragmatic when it comes to love, believing it is enough that he is a long-term relationship with a woman whom he intends to marry one day. When she bursts out in her musical number “That’s How You Know,” Giselle contests that one must be reminded over and over again, in little and seemingly trivial ways that one is loved. It is not enough to assume and take someone for granted.

Against the express wishes of his friend Jacob Kowalski, Newt Scamander of the Fantastic Beasts series compares Tina Goldstein’s eyes to a salamander’s. As a magizoologist, this is perhaps the height of adoration. Especially in Fantastic Beasts: The Crimes of Grindelwald, Newt makes it clear (however implicit) that he is in love with Tina though their lives have gone in different directions since the events of Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them. Contrary to Newt’s awkwardly endearing nature, Jacob Kowalski recommends Newt make the standard, formulaic declarations of love (“crazy about you,” “lost sleep,” “can’t live without you,” etc.). Comparing a woman’s eyes to a little lizard-like amphibian would seem to be the R.M.S Titanic of all romantic gestures, i.e. destined for disaster.

With Jacob’s approach, one could easily swap out either Newt or Tina with any random stranger and the delivery would be just the same. What any man might say to any woman. That Tina anticipates Newt’s attempt at poetic comparison before he is able to utter it suggests the intimate link between the two. Only Newt could have said this as an attempt at romantic overture and only Tina could have understood its meaning. The same could be said for a scene in Stranger than Fiction, when I.R.S. auditor Harold Crick offers baker Ana Pascal “flours” (as opposed to the usual of “flowers”) as both an apology and as a symbol of his romantic interest. How well these gestures are received is directly proportional to how much both parties are able to correctly interpret these obscure signs. Like a Wi-Fi network password, connection hangs on a single keyword. A moment of understanding is a promising sign when gibberish becomes the native language.

This requires a willingness to shed the noble garments of the romantic figure. The chief problem for Mumble in Happy Feet is his lack of “Heartsong,” something evident from his youth. One’s entire existence is built mainly upon one’s ability to eventually secure a mate through serenade. Mumble can dance as opposed to sing, but this method of expression does not translate in the same way a song would. No matter the love he may have in his heart for Gloria, shuffling and kicking one’s heels is a muted proclamation.

What is ironic here is that Mumble’s attempts at singing are what real-life emperor penguins sound like. What is unoriginal to movie viewers (like the public discourse on love) is startlingly and perhaps unappetizingly original to the movie’s characters (much like the beloved). This is a disheartening state of affairs for the lover because his only real concern is aligning himself with the beloved’s vantage point. He has little regard for similarity to public discourse because he is already well-aware of this sad fact. He is a failed lover like many before him. What use is there in knowing that? According to every other emperor penguin he knows, Mumble’s lack of singing ability means he has no chance of proving his love. This, according to Barthes, is one of the lover’s greatest fears.

When words fail, the lover must reveal his exhaustion via the body. Cold sweats, sleepless nights, spontaneous fits of uncontrollable sobbing convey the beloved’s affect on the lover in an immediate and visceral manner. As Barthes notes, “[a]morous anxiety involves an expenditure which tires the body as harshly as any physical labor” (Barthes, 203). In Sam Raimi’s trilogy of Spider-Man films, Peter Parker is forced to keep a great deal of heartache to himself because revealing his secret identity as a superhero puts his loved ones at risk. When Peter does unveil his emotions, his tears come as though he has accidentally left the faucet running.

This act of expression is often especially tricky for men, for whom tears are often unfairly seen as signs of weakness. According to Barthes, Peter “follows the orders of the amorous body, which is a body in liquid expansion, a bathed body” (Barthes, 180). In the film adaptation of Haruki Murakami’s Norwegian Wood, Toru Watanabe sobs uncontrollably after learning about Naoko’s death. However, he is not simply mourning Naoko, but Kizuki (Naoko’s boyfriend and Watanabe’s best friend) before her. Watanabe grieves for a part of his past, memories of his formative years, that have now been locked away forever with the death of two people he felt closest to in all the world. In this scene, he is alone on a rocky outcrop as ocean waves crash around him. It is as if he is sending his tears out invisibly, like a river empties unremarkably out into the sea. Tears become doubly performative, as evidence for both the lover and beloved of the gravity of this experience. Since the beloved he grieves for is not physically present, the film’s audience becomes a surrogate witness to his pain.

“I make myself cry, in order to prove to myself that my grief is not an illusion . . . I give myself an emphatic interlocutor who receives the ‘truest’ of messages, that of my body.”

(Barthes, 182)

Getting Directions

When it comes to love, one certainly requires a road map or G.P.S system to navigate. However, that would suggest one is entirely in charge of the destination. Habits and algorithms take a backseat to a free-floating pointer finger. Like a pile of hands gliding over the wood of a Ouija board, everything happening seemingly at random. However, Barthes would argue that those one is surrounded by, friends and foes alike, play as much of a role in regard to who one fixates on as the individual in question. To avoid the sharp pangs love inflicts on the body, the lover will seek guidance from the outside world in an effort to ensure his eventual success. Which route has the least amount of detours, pot holes, aggressive fellow drivers, police activity, etc.?

Both the films Ernest & Celestine and How to Train Your Dragon demonstrate how the world provides one with instructions on what is considered “lovable” and what is worth “loathing.” In the world of How to Train Your Dragon, it is dragons whom humans must fear. In Ernest and Celestine, bears and mice are sworn enemies. These feelings are instructed at a young age, so much so that they would never question these reactions as anything other than natural. The premise of To Sir with Love consists of a man, Mr. Mark Thackery, attempting to teach his students what is worthy of loving (disguised as academic attention) and what is not. He has to redirect and refine their anti-authority hooliganism into maturity by focusing on the basics of cooking, dressing up, and approaching substantial relationships.

The great tragedy of Thomas Hardy’s Tess of the D’urbervilles is that Tess puts her faith in people who do not have her best interests at heart. These errors can be easily rooted out in language. Tess D’urbeyfield is told her family is related to the noble D’urbervilles. She is sent off on her own to the D’urbervilles’s estate to improve the lowly D’urbeyfield family fortune, not realizing this trip begins the downfall of her reputation rather than an upswing. Not even the man not-so-subtly-named “Angel” can save her. The novel suggests relying too much on the suggestions of the external world is fatal for the lover.

“I know that I occupy the same position as my rival and that, therefore, all psychology, all value set aside, nothing can keep me as well from being, one day, the object of disparagement.”

(Barthes, 66)

Why does the lover risk using this sometimes faulty navigation system at all, even at the sublimation of his own instincts and judgments? The lover wants to devise a precise battle plan to avoid falling out of favor in the beloved’s eyes. He is aware this wish is ultimately doomed because he witnesses the example of other third-parties who express similar interest in the beloved. If others want the beloved as well but fail to secure her, it becomes a predictive mirror for the lover as to what dangers may await him. If others fail using similar romantic methods to himself, the lover envisions a sameness in identity between himself and other rivals for the beloved’s affection. Though he seeks external influence upon his battle plan, he must ultimately be singular (and not doomed to the garbage pile of the group) in the eyes of the beloved.

In Some Like It Hot, Joe and Jerry both have their eyes set on Marilyn Monroe’s “Sugar Kane.” However, both of them have a price on their heads and are dressed as women to hide from the gangsters pursuing “the loose ends” of their recent killing. Both Joe and Jerry are saxophone players, a red flag for Sugar as these types of men have been nothing but a series of romantic disappointments for her. Though both Joe and Jerry use their newfound womanhood as a means of getting close to her, neither of them can fully pursue Sugar without the threat of being discovered. To combat this issue, Joe and Jerry eventually take alternate routes of gaining Sugar’s attention.