Macleish’s play J.B. and the Problem of Evil

Chaos and impermanence exist at every level of the universe—from the life and death of stars to the creation and eventual destruction of the earth and every human, flower, and form of life on it. As a result, suffering is a key part of human experience, and because of this, mankind has searched for meaning in a world which involves inescapable loss, death, and pain. Archibald Macleish’s play, J.B., which tells the story of a modern Job, says “[there is] always someone playing Job…Millions of mankind burned, crushed, broken, mutilated, slaughtered, and for what?” (12).

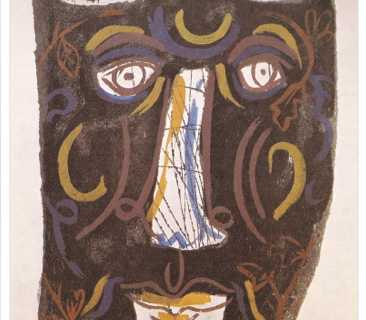

While it is completely understandable that humans question why suffering exists, J.B appears to believe that this “for what?”–this asking “why?”– is a mistake. By analyzing J.B.’s Godmask and Satanmask, I will show how Macleish’s play believes that mankind’s usual attempts to blame humanity or blame God fail to resolve the problem of evil because they assume there is a problem in the first place. In other words, these responses are trying to create justice by applying the roles of hero and villain to God and to man when there are no heroes or villains involved in suffering–just the nature of existence. The play suggests that mankind must take off these “masks,” step off “the stage,” and realize that there is no audience–no one to appeal to–because there is no one to blame.

In J.B., the Godmask represents the attempt to justify the problem of evil by blaming mankind; however, this response ultimately fails because, in order to villainize humans, it overlooks the presence of unjust suffering. The Godmask is described as “a huge white, blank, beautiful, expressionless mask with eyes lidded like the eyes of the mask in Michelangelo’s Night” (16). This description of the mask is intentional and reveals a lot about the idea that evil is the fault of humanity. First off, the mask is described as being “expressionless…with eyes lidded” (16). Basically, this means that when we blame mankind in order to make God the hero in the story of suffering, we close our eyes to evil and overlook the pain of others. In the beginning of the play, there is a scene that demonstrates this:

Sarah:[…]I love Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday. Where have Monday, Tuesday, gone? Under the grass tree, under the green tree, one by one. Caught as we are in Heaven’s quandary, is it they or we are gone under the grass tree, under the green tree? I love Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday one by one.

Rebecca: Say it again

Jonathan: You say it, Father.

J.B.: To be, become, and end are beautiful.

Rebecca: That’s not what she said at all.

J.B.: Isn’t it? Isn’t it?

Sarah: Not at all.

The light fades, leaving the two shadows on the canvas sky (42-3).

In this scene, Sarah is questioning meaning and describing loss, but when J.B. is asked to repeat Sarah’s poem, he can only speak of life as being beautiful because he cannot think of meaningless pain and loss when he believes in the justice of God. This almost makes him seem “expressionless” (16) or unfeeling, because he cannot empathize with the misery of others. In addition to being “expressionless…with eyes lidded” (16), the Godmask is described as “beautiful” but “blank” (16). This is interesting because Nickles, the character who wears the Satanmask, describes beauty as “the Creator’s bait” while the “Uncreator’s [is] nothing” (18). The Godmask argument is “blank” because of its empty logic, for the problem with blaming the sin of mankind for the existence of evil is that this idea does not seem believable–even to those who claim to believe it.

In fact, the play seems to think that the only reason people buy into the guilt of mankind is because without guilt “the whole world is meaningless. God too is nothing” (121). Humans would “rather suffer…knowing…[that they] earned the need to suffer” (123) than acknowledge their potential innocence. They would rather keep their idea of a good God and justice than acknowledge that God may not be the hero—that there may, in fact, be no hero at all…just existence and everything that comes with it.

In contrast to the Godmask, the Satanmask represents the attempt to justify the problem of evil by blaming God; however, this answer is insufficient because it uses the existence of evil to determine the character of God while ignoring the existence of good. The Satanmask is described as “dark…and open-eyed where the other was lidded. The eyes, though wrinkled with laughter, seem to stare and the mouth is drawn down in agonized disgust” (18). By describing the mask as “open-eyed where the [Godmask is] lidded” (18), the Satanmask argument claims to truly “see [the state of] the world” (22) and, thus, why evil exists. According to Nickles, “Hell… is to see. Consciousness of Consciousness” (22). Essentially, Nickles is saying that awareness of the true nature of life is the greatest agony, and Nickles’s response is to villainize the God who created life in the first place. Sarah demonstrates this idea in a conversation with J.B:

Sarah: […] almost mechanically […] God is our enemy.

J.B.: No…No…No…Don’t say that Sarah! God has something hidden from our hearts to show.

Sarah’s head turns toward him slowly as though dragged against her will. She stares and cannot look away.

Nickles: She knows! She’s looking at it!

J.B.: Try to sleep.

Sarah: He should have kept it hidden.

J.B.: Sleep now.

Sarah: You don’t have to see it: I do.

J.B. Yes, I know (102).

This scene is so interesting because both the Godmask-response (J.B.) and the Satanmask response (Sarah) are clearly illustrated. J.B. is telling Sarah to “try to sleep” (102) –to try to close her eyes to suffering; however, Sarah can only “stare” (102) at her pain (eerily echoing the Satanmask description). She “cannot look away” (102) from her need for justice, and, thus, she declares that “God is [the] enemy” (102)–the villain, rather than the hero for mankind.

At first glance, this response seems logical (at least more logical than the Godmask response); however, there is an important contradiction in the description of the Satanmask (and, hence, in its argument). The Satanmask’s “eyes, though wrinkled with laughter, seem to stare…the mouth is drawn down in agonized disgust” (18). The key words here are “wrinkled with laughter” (18), for wrinkles imply age and experience. In other words, the mask is a contradiction because it ignores experiences that bring joy and laughter in order to “stare…in agonized disgust” (18). It ignores beauty to stare at the evil that it wishes to project onto the character of God.

Interestingly, Sarah and Nickles almost view this hatred of God (and thus evil) as heroic, thus, creating their own sense of justice. The Satanmask is only the flipped version of the Godmask and, hence, both fail because they “[want] justice and there [is] none” (151). When Zophar says “without the fault…we’re madmen all…We watch the stars that creep and crawl…like dying flies across the wall of night…and shriek…and that is all” (127), he is describing not just the need for human guilt, but the need for something–for anything– to be guilty…to be the villain, because for many, it is upsetting to think that “[this] is all” (127). It is upsetting to accept the fleeting nature of existence.

Since, according to the play’s logic, both the the Godmask and the Satanmask arguments ultimately fail due to their pursuit of justice, J.B. implies that mankind should remove these “masks” and accept the futility of seeking a reason for suffering. When Zuss and Nickles wear the masks, “their voices…[become so] hollowed…that they scarcely seem their own” (21). This is important because the text implies that when mankind wears these masks–these attempts to justify the problem of evil–they become hollow and lose what makes them human. They either completely ignore suffering or they pretend that suffering is all that exists when, in reality, life is a mixture of good and evil… of beauty and pain and simple existence. At the end of the play there is a scene in which it seems that Sarah finally understands this, removes her “mask,” and, in doing so, helps J.B. remove his as well:

J.B.: Curse God and die, you said to me.

Sarah: Yes… you wanted justice, didn’t you? There isn’t any. There’s the world…Cry for justice and the stars will stare until your eyes sting. Weep, enormous winds will thrash the water. Cry in sleep for your lost children, snow will fall…snow will fall…

J.B.: Why did you leave me alone?

Sarah: You wanted justice and there was none–only love.

J.B.: [God] does not love. He is.

Sarah: But we do. That’s the wonder (151-2).

Sarah realizes that the search for an explanation of suffering and the need for a governing goodness are pointless because she realizes “there isn’t [justice]. There’s the world” (151) –there is life and all that comes with it. In the play, when Nickles and Zuss wear the masks, “the spotlight throws [their] enormous shadows on the canvas sky” (24). By saying this, J.B. implies that, in wearing these “masks,” mankind is really just casting shadows of their own ideas of justice onto the “canvas sky” (24) which, as Sarah realizes, “will only stare” (151) back at a broken humanity.

In this way, J.B. shows that when mankind tries to find heroes and villains to explain human experience, they are only “work[ing] themselves up into theatrical flights and rhetorical emotions, play[ing]…as though they had an actual audience before them in the empty dark” (3) –playing as though someone or something should be held accountable for the problem of evil, because that means that someone or something cares for the pain of mankind; however, as J.B. says to Sarah, “[God] does not love. He is,” to which Sarah replies, “but [humans] do. That’s the wonder” (152). This is why J.B. believes it is so important to take off the “masks” that create hollow impersonations of humanity: once humans stop asking for someone to blame, they can realize that the answer does not come from justice or God or the “canvas sky” (152), but rather it comes from something inside themselves.

In J.B., Mr. Zuss asks the question, “Who plays the hero, God or [J.B.]?” (140). Essentially, he is asking which of the Godmask and Satanmask arguments is correct; however, as the play suggests, both arguments are insufficient because they assume that either God or mankind must play the hero while the other must play the villain on the stage of human experience. It is only when mankind removes these theatrical roles and stops asking why–stops “play[ing]… as though they had an actual audience before them in the empty dark” (3) –that they can begin to move on from the problem of evil to, as Sarah suggests, the “wonder” of “love” (152).

When J.B. “[peers] at the darkness” (152), –when he realizes that he is “alone in an enormous loneliness” (114)–alone in a world that has no obligation to care for him in his pain…he laments that “it’s too dark to see” (152). Once he realizes that there are no heroes or villains involved in suffering–just the nature of existence, he does not know what it means to live anymore–what it means to be human anymore. So Sarah simply responds, “Blow on the coal of the heart, my darling…It’s all the light now. Blow on the coal of the heart…the lights have gone out in the sky. Blow on the coal of the heart. And we’ll see by and by”(153). Thus, instead of searching for heroes or villains, J.B. shows that mankind must seek the light that comes from within the hearts of men rather than the justice of God or the “lights…in the sky” (153).

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Love MacLeish’s absurdist approach and symbolism.

This is probably one of my favorite plays. I’m a big fan of the Book of Job upon which this is based, MacLeish does a great job of taking this biblical story and making it relatable.

I think I was in junior high when I read this. It made a deep impression on me, and there are lines from it I still remember and ponder.

Not a text that I know anything about, so well done on evoking my interest. Thank you for sharing your analysis.

An absolutely brilliant adaptation of the Biblical book of Job. No matter how you feel about the Biblical story, this play will shed new light on it. Beautiful, terrifying, witty, and poignant.

Read it twice. Performed it once. One of my favorite plays.

Helpful analysis of the play. I am a freshman in high school and the unit that we are in now is all about the Bible and how it relates to literature such as this book, J.B. So far, the book has been mostly arguing with the Book of Job and not that similar in most ways. As I finish reading it, I will have more to say…

I love that not only is it a quick read, but it is chock full of debatable topics.

Absolute genius play.

I think this play really misinterprets the book of Job, but it is thought-provoking and has a lot to say about the messed up world we live in.

Different twist to the story of Job from the Bible!

Although I haven’t experienced this text otherwise, the analysis was interesting and fun to read.

Powerful, poetic, moving. Thanks for the analysis!

This was a cool story, really inventive, and I liked how it was like people playin without knowing they were in a play.

I desperately look forward to watching this performed live.

Perhaps as a play in a theater this would have moved me. Reading it did not.

read this back in high school, just finished rereading it, v. good contemplation on good v. evil and faith

Interesting parallels to the Book of Job, still, a bit depressing and uneventful considering all that befalls the title character

I taught this in a course called The Bible As Literature. It makes a great companion to the Book of Job.

A thought provoking retelling that wrestles honestly with suffering and the goodness of God.

A really over-the-top high Modernist stab at depicting the events of the Old Testament’s Job in modern times, on stage.

Evil is such an interesting topic.

Bethany – thank you for this thoughtful analysis of J.B.

I personally have come to see the play as a variant of an orthodox interpretation of Job which runs along the lines of “Don’t ask the question about the nature of suffering and evil. It’s beyond human comprehension.”

That formulation is certainly not what MacLeish intends (he says the question itself is flawed and we should focus on love), but I find MacLeish’s “solution” to be rather traditional in its own way, although part of what MacLeish is explicitly doing is rejecting “traditional” interpretations.

Nonetheless, thank you for your clear and convincing interpretation of the play!