Marketing vs. Genre in Manga – How They Can Get Confused

How we classify the genres of manga/anime is a fickle thing. Lots of people treat manga and any Japanese artform as its own genre with phrases like “I think anime is for kids”, and “I think manga art is superior to DC comics”. It is important to distinguish what genre in relation to manga is before moving on. Manga and anime have genres and subgenres like any other artform. It’s how we classify these genres where it can get sticky. The prominent ways to define genre in manga is the terms: Shonen, Seinen, Shojo, and Josei. I believe that the terms shonen, seinen, shojo, and josei, shouldn’t be used as placeholders for genre, or even depict demographic well because of how the Japanese manga industry works.

The definitions of these go like this; Shonen is manga aimed at younger boys, Seinen is aimed at young men, Shojo is aimed at younger girls and Josei is aimed at young women. The main issue with this categorization is that these are marketing terms, not genre terms. This wouldn’t be a problem if these marketing terms weren’t used interchangeably with genre terms. The waters muddy even further when some of these categories seem to share conventions. These surface level similarities give the illusion of a through line, and people talk about these terms like genres with their own genre conventions.

Some examples of a “typical” shonen are: Naruto, One Piece, Bleach, and Dragon Ball. Some examples of a “typical” seinen are: Vagabond, Berserk, and Vinland Saga. Some popular shojo manga are: Fruits Basket, Ouran Highschool Host Club, Banana Fish, and Sailor Moon. Popular Josei manga include: Kids on the Slope, Chiyahafuru, and Paradise Kiss.

Each of these categorizations have “conventions” or vibes that people place onto such titles. Shojo is usually stereotyped as “girly” manga usually depicting flowery romance. Shonen manga is usually stereotyped as action heavy, fast paced shows with a sprinkle of the power of friendship. Seinen are usually seen as a grittier version of shonen, delving into grislier plotlines. Josei seems to be categorized similarly. More realistic depictions of life and romance that are deeper and more complex than shojo. But as we see, there are plenty of stories breaking these conventions.

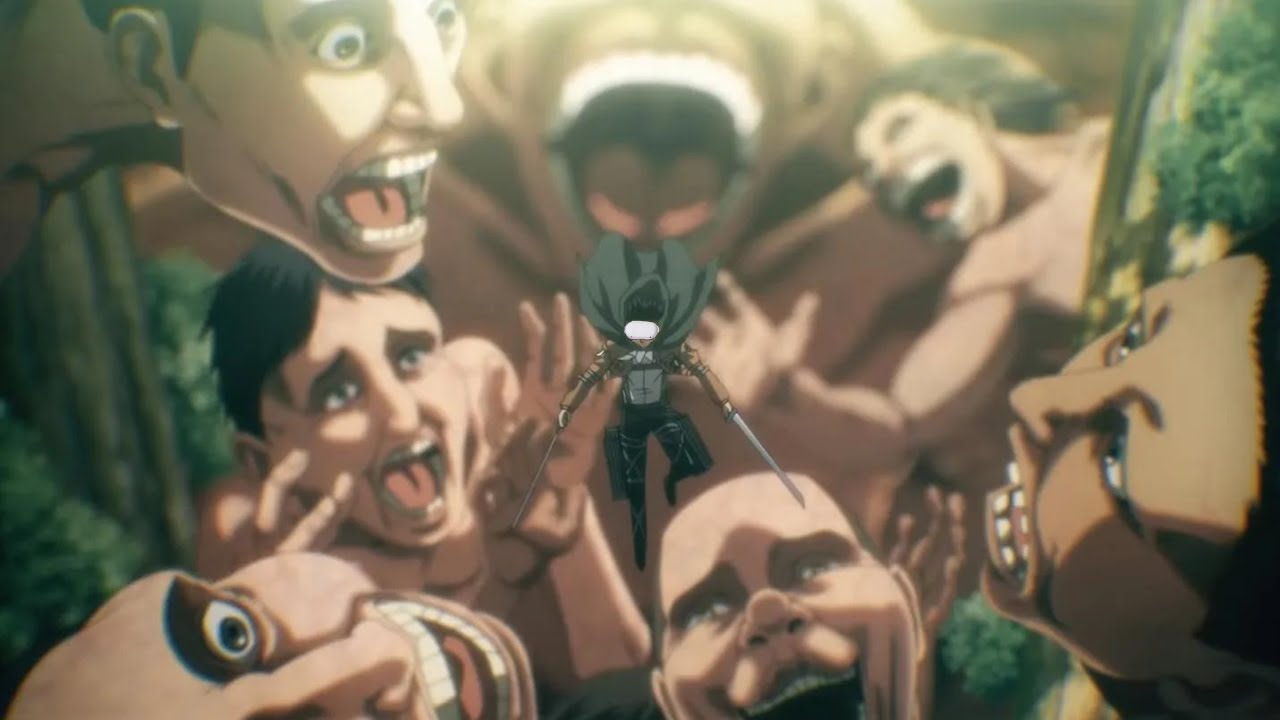

Examples of the discordance between these concepts can be seen in many different manga. Attack on Titan is a bloody, complex show with very mature themes and philosophies. The show tackles ideas like eugenics, anti-natalism, and many many shades of moral grey, yet the story is classified as a Shonen, the purported younger target demographic. Conversely, One Punch Man is an action-comedy which focuses on a colorful cast of characters in a mostly episodic format that focuses on battles and villains and humor. This seems like a very typical shonen but One Punch Man is a seinen show. Distressing and gory horror manga like the works of Junji Ito can be found in shojo, like Tomie, a classic horror story about a girl who is killed over and over again. She is regenerated in increasingly more disturbing ways. Tomie herself is a terrible person, constantly manipulating people to get what she wants. There are no role models and the story is complex and the themes it explores are nuanced.

Lets take an interesting case to expand my point. JoJo’s Bizarre Adventure. JoJo’s started weekly in shonen jump as a shonen manga yet transferred over to seinen to be published monthly ultra jump. The tone of the story didn’t really change too much to fit the new demographic. The biggest change was the art and length which had a vast spike in quality because the mangaka, Hirohiko Araki, had a month to write each chapter instead of a week.

So we see now that these aren’t genres and even the demographics can get confusing! So what actually defines a one of these terms? How does a manga get put into one of these categories? What is a shonen? Its simply the magazine the manga is published in. If a manga is published in Shonen Jump then its a shonen no matter the themes, content, or anything else. It’s a seinen if it published in a magazine like Ultra Jump as well.

How do these magazines work then? When a mangaka submits a work to a shonen magazine, the editors review it and suggest changes based on marketing to a mass audience. This marketing can sway in a lot of ways depending on the climate of the manga market in Japan at the time and what’s pushing volumes. Sometimes that is playing into the popular tropes of the day and trying to emulate the bigger recent successes. Some magazines even try to appease wider audiences with the manga they publish. This is a recent phenomenon in shonen magazines. This leads to manga published in shonen magazines specifically marketed towards women. (Prince of Tennis published in Jump Square for example.) With this constantly changing manga market, the genres and terms are getting more and more confusing.

The terms shonen, seinen, shojo, and josei, shouldn’t be used as placeholders for genre, or even depict demographic well because of how the Japanese manga industry works. At least for western manga consumption purposes I believe we should use more standard genre classifications such as: action/adventure, fantasy, romance, etc. to make manga classification more accessible and easier to understand.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Very basic overview of the genres and their target demos. I am interested in Tomie from how you described it.

The major diference from now and before is that manga writers have an AIM AUDIENCE that makes their material so even thou a manga is a shonen, teen girls and adults can also enjoy because they know what to expect. Shojos like Cardcapture Sakura are the same, with boys enjoying the manga/anime even if it’s aimed to teen girls.

RIP. There’s no senior citizen demographic in manga.

Not… YET.

The actual Target for the Senior Citizen is Seijin (Older Man).

Teenagers are searching for things that stimulate their imagination, emotional rollercoaster, things that make them think and push the boundaries of anything they’ve already see ; that’s the period when they start watching horror movies, playing violent video games and enjoying them;

it’s completely natural and makes sense for them to read something containing gore, violence and nudity (when you watch “IT”, play Dark Souls 3, there is nothing preventing you to read Berserk).

My little sisters started watching a lot of horror movies when they were only both 13 and 15 while I wasn’t particularly fan of them (and some of them were age restricted to them but they didn’t care).

That’s why I’m convinced that a 3rd of Tokyo Ghoul, Berserk, Monster, Kingdom fanbases are actually boys between 15 and 17 (I and my sister watched Monster when we were respectively 15 and 17 and it wasn’t more complex for us to understand and we enjoyed it).

Cuz it corresponds to things they’re looking for and enjoying.

As a personal experience, I played GTA Vice city at the age of 12, watched B Gata H Kei at the age of 14, read Ayako by Osamu Tezuka (while having nudity in it) at the age of 15, watched Monster at the age of 17 and not to mention every romance and Slice of Life Seinen anime I’ve watched while being under the age of 18 and also the fact that my Younger sister watched all of them at a much younger age.

You’re right. Tho I think everyone’s experience is different. I personally started watching horror movies regularly at the tender age of 8, and it wasn’t much later that I started playing horror games for example. My sister’s favorite game at age 10 was GTA SA too, lol

Demographics are but a guideline, and yes, I believe a lot of teens read a lot of Seinen… well, I don’t believe, I know.

I don’t think we can really talk about demographics without pointing out that shonen does and has always had a readership far greater than just teen boys. Certain titles like Kateikyo Hitman Reborn and Prince of Tennis largely floated on their female readership, especially when it came to merchandise sales, I’m sure the older female fans were a big money magnet. Gintama was also wildly popular with women.

Also when it comes to shoujo, both BL and yuri originate from shoujo, and a lot of soft BL or soft yuri content is still categorized as shoujo–basically the entire content of ZERO-SUM magazine for example, which leans on “not technically BL” titles like Loveless or Saiyuki, is shoujo manga (or josei, ZERO-SUM is very much on the line there/older demographic than your Ribons and Nakayoshis).

Shounen is not a genre, it is a target demographic for manga magazines, which feature series from every genre.

I agree! Many people talk about it like a genre which is what I was exploring

I have been wanting to get more into Manga lately, so this is very helpful.

I haven’t read manga in a long time. I still watch lots of anime but I’ve haven’t been reading manga lately. I’d like to get back into it. And you are right, we shouldn’t use the traditional labels to separate manga like that.

I adore manga! I collect it! Currently at around 600 volumes. Magical girls are my favourite genre! Cardcaptor Sakura was one of the first anime series that I got into as a kid. Paradise Kiss, Princess Jellyfish, Nana, Black Butler, Blue Exorcist, Food Wars, Kimi ni todoke, Naruto, Sailor Moon, Tokyo Mew Mew, Love Hina, Ouran High School Host Club, Black Cat, D Gray Man, Attack on Titan, One Piece, Oreimo, Bakuman, Death Note, Vampire Knight and Shugo Chara are just ones off the top of my head that I love! Funny enough harem manga was the first genre that I got into when I started reading manga! I was so happy to finish collecting Love Hina! I got the reprinted ones a couple of years ago! I think I’ve been reading manga over 10 years now!

Anyway, why not have genres? I think it’s easy to speak about manga with them.

I’ve been diving into more and more manga this year, and I get so confused with the genres and Japanese names for things.

It can get pretty confusing for fans outside of Japan. I completely understand!

Besides being a huge Hayao Miyazaki fan, I am totally a stranger in the Manga world.

I definitely think the demographic part is an important point to raise. After all, a lot of what becomes popular (here in the West, but in Japan as well) is shonen and seinen, and they tend to be watched by a lot of women rather than just men. As a female viewer myself, I tend to watch more shonen/seinen than shojo because a lot of the shojo that gets brought here and becomes popular is romance (a genre I’m not super into). While these labels can be helpful in some circumstances, the sheer variety in what is considered ‘shonen’ or ‘shojo’, and the fact that some pieces are hard to put in these categories, means that at the very least more classification is needed.

I bought my first manga recently and can’t wait to get more. Got a slighter better idea of what’s out there and how things are categorized.

When it comes to manga the cutesy romance’s and the slice of life are the best. I love shojo and basically the other genres you liked as well. Which is so strange for me cause when I’m reading novels I hate those kinds of books. Contemporary romance is like my least favorite type of book, I like horror and sci fi more.

I tend to like mahou shoujo, shoujo, Yuri/shoujo-ai, and slice-of-life manga best. Not that I never read any shounen or Yaoi/shounen-ai titles, though…. I just lean more towards things aimed at women.

I get the feeling that the demographics were more rigid about the types and styles of stories and art they featured in the past and are slowly becoming less so, to the point where it’s often hard to guess what type of magazine a lot of new manga are being printed in.

One interesting thing to note is that the work itself doesn’t determine the genre, but the magazine it’s published in. You could potentially end up with situations where thematically a work is mature but in a shonen manga.

Series like Vinland saga and Chainsaw man are good examples of that in which they were changed from shonen to seinen series.

Yeah that’s why I thought it was interesting to bring up JoJo’s because of the change in demographic when the themes were more mature much before the switch. Also Attack On Titan is like, the poster child of this phenomenon with all of its blood and mature themes in a shonen magazine.

As someone who loves shojosei, i love that i can get a similar vibe/style frm some shonen or seinen series.

This has actually inspired me to check out more Josei series because it seems like the demographic has a big focus on very emotionally mature and honest stories that explore interesting sets of concepts, circumstances, and ideas without being pretty obviously messed up like seinen series are. Also, in general, I have seen too few series in that demographic. the only true Josei series I have seen are March Comes in Like a Lion, Showa Genroku Rakugo Shinjuu, and Violet Evergarden. Personally, I don’t consider Chiyahafuru to be a true Josei story. in terms of emotional maturity, it is closer to a shounen series than anything else.

BTW, when I see something categorized as a “Josei” I don’t think: “oh, it’s in a Josei magazine”; I think is:” oh so it’s an emotionally mature and honest series that depicts people and life in a very realistic and honest manner. and unlike most seinen, the ugliness of the world isn’t portrayed by obvious physical violence but in a more subtle and personal way”…

Horror Anime is what got me into anime.

My introduction to anime was Ronin Warriors and Teknoman as a kid, though at the time I didn’t understand that they were imported from Japan. I also remember that every time my family would go out to rent movies, I’d pay a visit to the aisle with the La Blue Girl movies just to look at the boxes. I don’t think they were ones that had super graphic art on the boxes, but they were definitely titillating.

I’ve been watching anime for 12 years and don’t know the actual specific definitions behind a lot of the genre titles

Wow, how many anime have you watched? Just curious.

I know you didn’t ask me but I’ve watched around 100 but never got around to figuring out the the words ment.

I generally like Seinen manga, because i like the elements infused within the genre. such as ideological warfare, twisted twist, gloomy story line, character driven storyline that incorporates lots of personal struggle (by struggle i mean “struggle” not just a shonen type of p.struggle) the more tragic the better. Manga like Scum’s wish, some of the Fate series, Darker than Black, FMA etc.

I always find the Harem and Reverse Harem so entertaining.

I have been watching anime for 5 years i dont even know these genres even existed.

What genre ate animes like kimi no na wa, weathering with you, a silent voice etc is it slice of life

Yes because it revolves around reality and their lives and relationships.

I have been an American comic reader since I was 7 years old, I’m 36 now. It wasn’t until after mid heroic age of marvel/ blackest night era was when I jumped ship to Manga.

It’s easier to get my hands on, the genres are also easier to navigate through. And the stories are superb. Consistent writer on a title, definitely helps, that’s for sure

You didn’t like Geoff Johns/Peter Tomasi Green Lantern Runs?

Always thought of the “marketing” terms as genres— interesting to consider where the overlap lies!

Gore and horror are different? Most horror shows have some Gore I always thought the genre was gore…

my genre combo; boy, man, mecha, drama, political twist

my favorite anime results = Attack on Titan & Gundam Iron Blooded Orphans.

I’m just wondering would SAO be like shounen or seinen?

I was thinking of harem mostly tbh, every girl he met was in love with him.

Pretty sure SAO is technically shonen, but since it’s based on a light novel and not a manga it gets kind of muddy.

i dont belive that shoujo is only for girls and shonein is only for boys. both genders enjoy them without thinking about the genre.

I like manga

I find the categories limit what’s made available for people, I honestly think that they shouldn’t be used.

Great point about how muddy these conversations get. On the one hand, we know that demographic terms don’t constitute genre—shoujo, for example, isn’t all just romcoms and can tackle subject matter that’s just as dark or serious as a shonen series. On the other hand, even across different genres, we end up acknowledging and agreeing upon trends and tropes that are consistent within each demographic. It poses the question of how demographics can be NOT defined by genre and yet have very recognizable genre conventions, whether in art style or content. I think you have a good point that a move toward more genre-focused classification would be helpful. However, with that we end up losing progress in other ways; for example, shoujosei being written primarily by women and for women is a huge draw of the demographic, and doing away with demographic distinctions could negatively impact that.

Incredibly interesting point that I did not think about. I agree 100% with that last part. Ignoring that aspect of the demographic divides would negatively impact progress made towards women in manga spaces in Japan. Thank you for this thoughtful comment!

I just think what makes shonen “shonen” and shoujo “shojou” is such an outdated concept since the anime industry is just categorizing certain genres into gender

It’s great that you take the time to break down the difference between manga genres and demographics. From my admittedly limited understanding, some stories that seem more adult-oriented get published in shounen (or in some cases shoujo) magazines simply because teen magazines have wider reach and are marketed more heavily. Because of this, publishing in one of these teen magazines leads to more publicity for the authors than trying to publish in, for instance, a seinen magazine would. My personal favorite anime, Shiki, seems to be an illustration of this phenomenon, though I don’t know this for a fact. Though the anime is clearly aimed at mature audiences, the manga ran in a shounen magazine. The series began its life as a collection of novels, which I assume were also more adult-oriented, but the manga greatly expanded upon the role of a teenage side character named Natsuno Yuuki, eventually making him out to be a main character in his own right. I can assume that this was done in order to make the series more attractive and relatable to an audience of teenagers. When the anime came out, it relegated Natsuno to a supporting role again (albeit a much larger one), and basically reduced him to a plot device later in the story in order to keep him involved.

Would like to become a manga writer