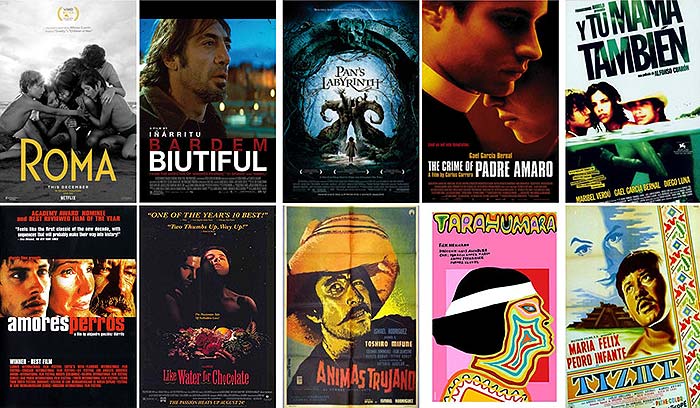

A Portrayal Of Mexican Cinema

Mexican cinema has produced some significant films across its century of production, though after its golden age ended in the 1950s these became fewer and fewer, as production turned towards low end (but profitable) market of low-budget westerns, horror movies, wrestling films, and sex comedies. As a form of ‘national cinema’ Mexican output in the 60s, 70s, and 80s seemed nothing special as it had lacked a clear identity. The issue with early Mexican cinema was that it had harmed the national representation of Mexico as it had very much conformed to very limited stereotypes that were conveyed negatively by the western media. The reason Mexican cinema had produced films such as horror, wrestling, and action is because they were genres that were more accessible to an international audience but had failed to represent real the Mexico and Mexican issues.

But at the start of the 1990s, a new direction and dynamism in Mexican film began to impact on the world scene, and Novo Cine Mexicano (New Mexican cinema) was born. New Mexican cinema was a movement, a form of ‘new wave’ that began in the early 1990s and is remarkable in the fact that it has been populated almost completely by unknowns, from directors and writers, through its cinematographers and actors, catapulting them to fame. The movement has developed from a purely Mexican base, through collaborations with Hollywood and the influence of European cinema, to a truly international cinema.

In its emergence, Novo Cine brought a wave of new talent on the production side and this was matched by a similar wave of new talent on the acting side. Both groups began to function as an ensemble, which in turn meant that there was constant work and therefore a constant opportunity for development. The success of the national cinema has allowed talent to work on bigger projects and collaborate with Hollywood, which means that their work can reach a mass international audience. (Gravity, Birdman, Revenant). Novo cine Mexicano has allowed the national cinema to regain credibility moving away from stereotype to provide a more authentic depiction of Mexico and provide a platform and voice for them to convey important messages

Both of the films Amores Perros (2000, Alejandro Gonzalez Iñárritu) and Sin Nombre (2009, Cary Fukunaga) deal with a wide variety of issues that are relevant to a broken Mexican society. Issues such as class divide, poverty, gang violence, and the theme of escape all serve to justify a new wave movement that highlights the real issues that are faced in Mexico.

Neo-Realism

One theme that is relevant to this New Mexican cinema is Neo-Realism, which is an authentic approach to filmmaking. Neo-Realism conveys contemporary issues of a national cinema. The birth of New Mexican cinema had opened the floodgates to a new generation of filmmakers who wanted to tell new stories that had little to do with monsters, action heroes, or cowboys. Instead, they seemed to embrace the neo-realist style of a ‘cinema of the humble’ where lives float on a sea of politics, poverty, violence, corruption, and the emptiness of a malfunctioning society at odds with itself, reflecting a modern Mexico. This commitment to showing the ‘real’ Mexico makes neo-realism the true ‘National Cinema style’ dedicated to overturning the stereotypes and misrepresentations of Mexico and Mexicans found elsewhere within cinema and other media. Many of the filmmakers including Iñárritu are from a documentary background, and accordingly, a realist or neo-realist influence is evident in much of its output.

Amores Perros fits into the Mexican national cinema style of neo-realism through using conventions of neorealism, to create a gritty and raw interpretation of Mexico, such on-location shoots and local talent to add to the authenticity of the film. The film is shot using more documentary-style cinematography such as longer take, and more handheld camera work to create a sense of realism. Its themes of poverty, corruption, and class divide move away from stereotypes to commentate on real Mexican issues, make it neo-realistic in design.

We can see these conventions of a Neo-Realist style in the Octavio and Susana sequence, making the film fit within the expectation of Mexican cinema. Through the location settings and use of local Mexican talents, the film conforms to neo-realism only Gael Benicia (Octavio) is a recognized actor. The confined setting of the house that Octavio lives in relates to real Mexican issues around poverty. The use of a handheld camera adds to the documentary feel and places the audience in an observational perspective which humanizes the camera. Octavio during the sequence is watching a classic Mexican horror showing how the director Iñárritu is giving a nod to early Mexican cinema.

Although Iñárritu conforms to the Neo Realistic approach of Mexican cinema; he however also incorporates his unique auteur style, which is more stylistic, moving away from the conventions of documentary and realism we expect to see. The style of the film, which is made up of episodes that jolt backwards and forwards, is the antithesis of realism. Its frantic camera work and restless movement are far removed from the long takes used in Italian Neo-Realist films. Similarly, the editing rhythm and general pace of the film departs from realist strategies. The fact that the film spans several story strands makes it seem less of a realistic slice of life. The use of music (non-diegetic sound), heightened diegetic sounds, and filters that give the images a stylized look further undercut the sense of authenticity. The result in Amores Perros is a highly unusual hybrid of realism and flamboyant, extravagant stylistic direction fitting with Iñárritu’s auteur approach of directing.

The Dog Fighting Sequence Iñárritu’s reinforces that Iñárritu challenges expectations of Neo-Realism, and can be argued to be the antithesis of realism (Challenging conventions of realism). Iñárritu challenges aspects of neo-realism cinema by imprinting his style on the film, his use of the bleaching process in editing manipulates the colour filters, to add a blue and green tint which takes away from the realism of the footage as it is no longer raw. The dogfighting and car chase sequence are shot through and overuse of close-ups and fast-paced editing, to create a more frantic and stylistic approach – the film lacks traditional long shots which go against neo-realism as it doesn’t allow the audience to orientate to the reallocation. The Nonlinear narrative and storytelling, starting and returning to the crash sequence, goes against conventional documentary making.

Alternatively, Sin Nombre also adheres to Neorealism but chooses to show this differently. The film goes to great lengths to convey the dangerous journey undertaken by Mexican’s and people from South America, as they seek a better life in America and attempt to cross the border. Fukunaga to depict this journey realistically, not only used neo-realistic approaches also immersed himself within the world of the immigrants, taking the road with them to discover the actuality of how and why Mexican’s choose to risk everything to escape the country.

From the documentary Fukunaga realistically realistic conveys the journey taken by the immigrants taking elements of neorealism to the extreme by actually immersing himself in the journey to border the migrants take. Like in the documentary images such as the Guatemala crossing seen in the film not only commentates on the Mexicans journey but also migrants from larger areas of central America, seen is Sayra’s story. The train in the film is referred to in real life as ‘the beast’ because of the danger it presents desperate migrants who are robbed, exploited, and fall off during its journey. Sin Nombre realistically conveys the sheer mass of people in poverty that try for the border making the 200-mile trip, in which only 40% of 1000 people day make it, and only 5 in 100 cross the border.

Fukunaga utilizes a neo-realist style associated with Mexican cinema to convey the theme of crossing the border. The montage of images of migrants cooking, cleaning, braiding each other hair isn’t acted and instead, raw footage from the director experiences travel with the people fitting into neo-realism and proving the realities of the life they live. The camera adopts a further distance through a longer lens, allowing the audience to be placed in an observational position –less biased and more authentic. The style of handheld camera, local talent, and reallocation fit with the convention of neorealism.

Sin Nombre as well as being neo-realism also fits into the road movie genre, another popular stylistic approach adopted by Mexican filmmakers. Sin Nombre carries over many of the conventions of a road movie genre. Many Mexican films like Sin Nombre commentate on the journey through Mexico to the American border. Through the characters of Sayra and Casper they fit into the archetype of the road movie genre through their binary oppositions, which make the narrative more dramatic and create conflict, where ultimately, they put differences aside to form a bond. The vehicle (train) itself provides a place for the young characters to transition into adulthood through their shared experiences on the road.

Crossing The Border

The Crossing of the border to America can be said to be a theme of Mexican cinema in its own right. Sin Nombre like most Mexican cinema commentates on the theme of crossing the border and how the protagonists hope for a better life, escaping the poverty and violence prevalent in Mexico. Through the dual narrative, it depicts both Casper and Sayra’s stories, as they journey across the country to escape their problems and environments. Cary Joji Fukunaga utilizes a dual narrative to comment on the theme of immigration and crossing the border because it allows the film to show a wider perspective of why people in poverty in Mexico choose to escape and cross the border. Casper seeks to escape violence and gang culture, while Sayra seeks to escape South American poverty with the dream of starting a better life in America. The dual narratives mirror each other to show the shared problem of poverty in broken Mexico. The introduction shots of each protagonist are constructed to convey the aspirations of escaping Mexico and embarking on the immigrant’s journey to the border. Both the introductory shots are over the shoulder shots of the protagonists looking outwards, connoting them dreaming and aspiring to escape. The fact that the camera is positioned behind the characters maybe suggests the lack of identity of people in poverty in Mexico. The closed framing of the walls in the foreground of Casper’s Home, and the clotheslines of Sayra’s rooftop, entrap the characters in their environments. The long shot of the slums highlights the extent of poverty in Mexico.

Sin Nombre highlights the dangers faced by immigrants hoping to cross the border. As the narratives of Casper and Sayra collide the film begins to highlight the more distressing aspects of trying to escape Mexico. The train Robbing Sequence conveys the dangerous shift in Sayra’s journey. The rain acts as a pathetic fallacy, the suddenness of the rain connotes how the mood can quickly change for the migrants and become dangerous without warning. The discordant non-diegetic score conveys the more foreboding and intense atmosphere linking with the rising danger faced by migrants as they robbed by the gang members. The closed framing as Sayra and the other migrants cower under the raincoat’s signals their entrapment, while the high shot connotes their vulnerability to the Casper and the other aggressors. The reason why when Sayra decides to continue her journey of escape with Casper rather than her own family and father is that she is safer with Casper over her own family, as he fulfils a more protective figure in a poverty-stricken and violent Mexico, where it is the survival of the fittest. Sayra shows a sense a naivety that exists in immigrants, as they take unnecessary risks to try to guarantee their safe passage to the border.

Mexican’s migrate over to the USA illegally on the back of the ideology a hope of the American Dream, choosing to risk everything for the chance of a better life away from a broken Mexico. The USA offers immigrants the dream of a better life than Mexico. The opportunity to gain employment and earn money, safety away from the corruption of Mexico, and the possibility of education and be able to provide a better life for their family. the final images of Sayra convey life in America for Mexican immigrants crossing over illegally. As Sayra walks past the prison-like bars of the fence, a police car drives past, to suggest the idea of how illegal immigrants live in constant fear of being deported, and viewed as criminals. The long framed open shot of Sayra as she walks through the car park connotes her isolation and uncertain future across the border. The long shot of Sayra’s brother embarking on the same journey despite the death of his father shows the risk immigrants will take in the search for a better life in America.

Gang Culture

Many people in Mexico are forced into a life of gangs and violence as a way of survival. The gang portrayed in Sin Nombre has its roots in the civil war in El Salvador, where the U.S.-backed death squads and military killed tens of thousands of people and forced thousands of others to flee to the United States. This left half of the population of El Salvador under the age of 18, where these children were forced into a life of crime and violence that soon spread to Mexico. The Mara Salvatrucha gang, also known as MS -13 and La Mara, is known to be one of the most dangerous gangs in the world. Gangs prey on younger adolescents for their compliance and their need to belong. The Maras abroad in Central America and Mexico tend to initiate children as new members who were left by their immigrant parents and grow up in a rough neighbourhood.

Gang life is often seen as an acceptable alternative for young people who live in poverty. Smiley represents the generation of young Mexicans who turn to gangs for a sense of belonging and safety as they are from broken homes and lack positive adult role models. Smiley turns to the gang because of a lack of alternatives, the lack of opportunity in a poverty-stricken Mexico means that crime is the only way to survive. Casper at first acts as a mentor figure to Smiley, introducing him to gang life and teaching him how to survive, in the violent backdrop of poverty-stricken Mexico. Casper and smileys narrative trajectories convey the cycle of violence and how younger males are initiated into gangs as readymade preplacement for older members who die, go to jail or try to escape. Smiley represents Casper’s life in the gang previously who at first needed a sense of belonging but in the future has become disillusioned.

The appeal of gang life is conveyed in the Mara headquarters sequence. During this scene, Smiley is welcomed into the home of the Mara 13 leader, Lil Mago, for the first time. The non-diegetic melodic score and the warm colour filters throughout the sequence, connote gang culture positively and inviting. The closed framing and small setting create an enclosed and close unity between the characters and a sense of family. Lil Mago’s diegetic dialogue “Your part of a family of a 1000’s brothers” reinforces the sense of belonging that Smiley and younger people seek. Lil Mago is constructed as a father figure, framed dominantly on the left holding his baby close to him, this allows the character to be more relatable.

However, some of the disturbing aspects of gang culture are still present and can be viewed as still having elements of danger attached to it. Despite this warm and inviting atmosphere, the dangers of gang life are quickly realized when Smiley is forced to kill a rival gang member for the first time. the melodic music cuts out and is replaced by the heightened sound of the ringing gunshot, to emphasize the reality and shock of how his young life and innocence have been corrupted. The closed framing of the setting could suggest Smiley’s entrapment and how he has sacrificed his freedom by joining the gang. The close images of the dogs eating human flesh contrast the visuals of the gang happily feasting together alludes to the dangerous and violent undertones that exist within joining a gang.

For Smiley to be accepted into the gang and be considered part of the family, he has to go through an initiation process and take a rite of passage. This process is used as a way of assisting the transition from a boy into a man. The initiation of Smiley’s 13-second beating connects to the real-life gang ritual carried out by the mara-13; the rite of passage linked to violence is symbolic connect to proving elements of masculinity. Smiley being able to prove his manhood. He assigned the nickname ‘Smiley’, which shows how he has been given a new identity connect to the gang, leaving behind his life as a child. The white blood-stained shirt connotes the corruption of innocence and Smiley transition from childhood through violence.

Class Divide

Additionally, the themes and ideologies within Mexican cinema highlight social equalities and exclusion that exist in the country. Mexico is a country that has high levels of poverty, with nearly 45% falling below the poverty line and over 40% unable to get access to basic health care. Large pockets of Mexico remain uneducated, while millions are unemployed leading to Mexican people migrating abroad in search of a better life. These themes and issues of class divide in Mexico are apparent within the context of Amores Perros. These contrasting aspirations of class have led to a country of the’ haves and have not’s’, creating a social divide existing of extreme poverty and middle prosperity.

Amores Perros uses a portmanteau narrative which has been used to tell three independent stories that collide during a violent car crash. The narrative strands explore the lives of working-class Octavio, middle class, Valeria, and the final narrative strand explores the life of hitman El Chivo. The film explores themes of class divide and conveys strong ideologies around poverty in Mexico. However, although the text highlights social exclusion and poverty, the film also subverts this theme by creating a likeness between the characters despite their differing social circumstances. This suggests a broken Mexico which has deep underlining problems.

The issue of class divide is captured in the introduction to the characters’ homes. When we first see the working-class home of Octavio, Inarritu uses low key lighting to suggest a sense of instability attached to the characters in poverty. The run-down décor and cluttered use of props create an uninviting and poverty-stricken environment, this is further reinforced via the use of closed framing and close up shots, all of which create a claustrophobic setting. This emphasizes how people in poverty are forced to live in crowded and small homes. Octavio becomes mixed up in gang violence as a means of escaping poverty; this is another key theme that justifies a national cinema context. In juxtaposition to this is Valeria’s home, she lives in an affluent high-rise penthouse which places her literally above the poverty line in Mexico. Open framed camera movements suggest stability and freedom attached to middle-class life; this is further reinforced through the luxurious décor, high key lighting, and inviting bright colours. The art upon the walls and images of Valeria modelling convey a sense of self-indulgence and arrogance, this suggests that Valeria is ignorant of the issues of poverty in Mexico.

The use of this narrative approach emphasizes the class divide by completely isolating class into separate story strands. Suggesting a Mexican society where classes don’t overlap and mix. The car crash is one of the only times the classes collide, suggesting that only through acts of violence and chaos do they find themselves in each other company. One of the occasions these portmanteau narrative stories overlap is when Octavio and Jorge are watching Mexican TV, and we are introduced to the celebrity model Valeria. The television is used as an aspirational window for people in poverty to look into middle-class Mexico, Valeria is placed in an aspirational light the working class should envy. Both Valeria and Paulo perpetuate a westernized version of beauty and appearance, move away from version Mexican representations to a more middle-class view of what was deemed acceptable. The television acts as a physical barrier that separates and creates a divide between classes in Mexico.

During the hitman sequence, we develop the sense that El Chivo operates beyond the class system. The scene opens with a medium close up shot which highlights El Chivo’s run-down aesthetic, his long hair and dishevelled costume allow the character to blend into Mexican society, as people often ignore the homeless. The middle-class victim is framed via a medium close up, his costume juxtaposes El Chivo’s, further reinforcing the class divide. After performing the hit, El Chivo can escape easily and blend back into Mexican society where he is ignored.

However, it can be argued that the character of El Chivo cannot easily be categorized within the class system of Mexico, instead, he is a character that exists outside of class. At first as the spectator, we will initially place El Chivo in poverty because he is living as a tramp. however, as the narrative progresses, we discover that he lives this way through choice and chooses to lives with lower classes to remain invisible to society, which fits his role as a hitman. His past conveys how he is from a traditional middle-class background, used to be a professor/scholar before turning into an activist to fight against the corruption in Mexico. El Chivo carries attributes from both sides of the class system, use symbolically to suggest an overall broken Mexico.

A Broken Mexico

The themes of neo-realism, crossing the border, class divide and gang culture show us a broken Mexico. The film Amores Perros through its themes of class divide conveys strong ideologies around poverty in Mexico. However, although the text highlights social exclusion and poverty, the film also subverts this expected theme by creating a likeness between the characters despite their differing social circumstances, suggesting an overall broken Mexico with more deep underlining problems.

Cofi contrasts with Richie, the small white Maltese who exemplifies the stereotype of the feminine. Richie is loyal, has little intelligence, and utilizes his cuteness to manipulate and achieve his objectives. The model’s tale also leaves one hanging. This tale may also be viewed from the canine standpoint. Richie, unlike Cofi, is a lap dog, as beautiful and delicate as his owner. Richie is Valeria’s constant companion and emphasizes her refinement. He is exactly like the mascot one could expect of a woman with the physique and temperament of the pampered. Richie and his owner are a mere illustration, a saccharine portrait of profound love between a person and her mascot. Both live in the princely, domesticated world of the Mexican bourgeois, which contrasts with the nasty world of the other protagonists who constantly fight and rebel against poverty. Richie is not ferocious like Cofi, nor does he show to have developed instincts or sagacity. Even the tricks that Valeria has taught him are performed unconvincingly. When his toy ball falls in the hole of the floor of the apartment, Richie runs to fetch it, but cannot find his way out. His helplessness is like a brooch for Valeria.

Valeria is a model valued for her great physical beauty. The accident alters her life completely: she loses her job, her relationship with her lover deteriorates rapidly and she loses a leg. From being a beautiful, educated, and delicate woman, she becomes a barking bitch, just like Richie. She insults and shouts at Daniel uncontrollably. She feels helpless and claustrophobic in the apartment where she is convalescing. Her situation is like Richie’s, who, also helpless and claustrophobic, is trapped under the floor and is being attacked by rats.

Strong connections to the canine realm are also evident in the tale of the professor. In it, dogs constitute an invisible hand known as “petting the dog”, utilized normally by the screenwriters to subliminally influence our opinion of the character. In the beginning, it is easier to sympathize with the dogs than with El Chivo, but, when this man who does not seem to love anyone reveals a weakness for the dogs, his image softens and the audience starts sympathizing with him. El Chivo utilizes the dogs as substitutes for people, transferring his love to them.

When Cofi instinctively kills his other dogs to exercise his territorial power, El Chivo becomes possessed with a reflexive vengeance. Cofi is spared. El Chivo contains himself when he realizes suddenly that he is an assassin just like the dog. From that moment on, El Chivo is going to try to mend his ways. Cofi, whom the professor re-baptizes Blackie, functions as a therapeutic agent by becoming his companion of adventures. Like Sancho and Don Quijote, the professor and the dog also invert their roles of master and servant when, in a symbolic scene, Cofi exhibits more wisdom and humanity than his putative owner, by letting him see the “light” about his true identity.

Character transmogrification also has its dual in the canine realm. When Cofi is introduced he is just a pet. He is neither adorable nor admirable. When he is made to fight with other dogs Cofi executes his job with aggressiveness, an inherent aspect of his nature. Cofis is divided between two brothers: Ramiro, who is his owner, and Octavio, who cares for and utilizes him in the fights. Motivated perhaps by jealousy and avarice, the brothers fight instinctively and bestially-the the same way as the dogs do-to establish their primacy. Octavio gets aroused when his brother makes love to Susana. Like Cofi, a docile housedog who becomes a fighting dog, Octavio gets transformed from a harmless youth into an assassin.

For his personal development, Octavio’s actions represent regression more than progress. He not only does not become self-sufficient but rather loses everything: his only brother, his friend, his lover, his family, and his dog. All his attitudes and plans are programmed for failure since the beginning. There is no indication that he has the resources needed to carry them out. Susana never assures him that she is going to leave with him and in the end, demonstrating a Marianist attitude, she opts for staying with her husband, even though he abuses her. From treating her with tenderness initially, Octavio starts pressuring her to have sexual relations.

When analyzing the symbolism of the dogs within Amores Perros they are of significant importance and are a reflection of their owner’s circumstances within a broken Mexican system. In the final dog sequence, Octavio and cofi both use violence as a means to survive and escape. Octavio and Cori work on instincts and are self-destructive, as they ruin their escape from poverty through greed and aggression and don’t know when to stop. Whereas during the observational sequence both El Chivo and Blacki are used to help each other escape and create a better life for themselves. El Chivo and his petting dogs both have a sense of not belonging and are rejected by a broken Mexico that fails to support people in need.

El Chivo like his petting dogs represents although choosing to reject the broken system, reluctantly accept the corruption of the Mexican handouts to survive, forcing El Chivo to work with a government he initially fought against. El Chivo and his petting dogs both have a sense of not belonging rejected by a broken Mexico that fails to support people in need. Throughout the narrative it is El Chivo through his invisibility within the society gains the ability to see the hypocrisies and hopelessness within Mexico. As the film draws to a close El Chivo turns his back on Mexico and chooses to escape his broken nation.

The resolution of the film conveys how El Chivo is giving up on Mexico and choosing to escape. Through the montage of El Chivo shaving and having a shower, connotes the characters reinventing himself and seeking a new identity, much like the reinvention of Cofi into Blackie, a chance for a clean slate and transformation into more acceptable and westernized representation. The phone call to his daughter acts as confession and apology to how he was unable to change the corruption in Mexico and instead chooses to escape as he sees Mexico as broken beyond repair. The open-framed long shot of El Chivo walking across the vast open desert is symbolic of the journey taken by many Mexicans in their immigration to the border. This theme of escaping a broken Mexico taps into larger Mexican issues and illegal immigration to America. El Chivo possibly sees fleeing to America as an only alternative to make a new life and make his family proud.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

While the international movie circles are familiar with the independent efforts like Y tu mamá también, Padre Amaro and Amores Perros, most of the Mexican movies are pretty awful. The mainstream movies are basically a Mexicanized Hollywood, only worse. Lots of “comedies” are basically Rom-Coms or stale rehashed humor; if you’ve seen one of these movies, you’ll know the plot for all movies released 5 years earlier or later. And it isn’t even a recent trend; going all the way back to the so-called “Golden Age” of Mexican cinema, the theaters were rife with Hollywood-wannabe movies or blatant ripoffs. There’s even a Beverly Hillbillies ripoff called “Beverly de Peralvillo”, though in the traditional Mexican tradition the ripoff Beverlies aren’t rich. In fact, some of the best movies from the Golden Age were either box office bombs, or outright banned like Luis Buñuel’s Los Olvidados.

There is some good truth to this. When Mexican movies hit the cinema, they have to deal with sceptic Mexicans who believe it’s going to be yet another stupid movie, and 8 out of 10 times they’ll be right.

The arts are so strong in Mexico. It’s 25 years since I visited, but still the impressions stay with me — the street food, the architecture, the markets, the history, the weird volcanic lava fields, and so on. Distinctive art and character shines through everything. It’s intense.

I really enjoyed Amores Perros.

I am trying to read John Huston’s biography or just skimming the parts where he lived in Mexico. Treasure of the Sierra Madre and Night of the Iguana are great films that are set in Mexico.

Is Pan’s Labyrinth considered as Latin Cinema? Because it was shot in Spain, yes, it was directed by Guillermo del Toro but when he came with mexican producers to introduce the idea of the film, no one believed in him, that’s why he went to Spain.

Spain is a REAL Latin Country. It’s not Latin-American CInema, but it’s definitely Latin Cinema.

Thank you. Great introduction to the rich culture of Mexican cinema.

Mexico’s film industry has been always very strong from the golden age till now. Besides the three amigos, they have all kinds of visionaries. Way more than many countries but coming closer the number one film director export since forever, France.

Watching Roma and I was embarrassed by the sense of entitlement of the middle class family. They had no qualms about lording it over their servants; scolding them for not cleaning up their dog’s shit. A great film.

They’re unaware; for decades indigenous people have been “invisible” in Mexico; not seen on TV nor in magazines.

The beauty of the film was the parallel events of the two women protagonists being abandoned and finding a humanity which breached the class divide.

Sin Nobre was weak. It looked good, despite the camera being stuck on the roof of the train for far too long. But it had not an ounce of subtlety. The villainous mobsters were very evil, you could tell, by their horrid tattoos and habit of being beastly to the young. The camera lingered indulgently on the faces of the main characters, as if hoping for expressions that would tell of their deep emotional torture. But only came away with cliches.

I laughed out loud when one of the goodies fell off the train, never to return. Every bit of the plot was predictable, and I was shouting out the subtitles five seconds before they appeared. I didn’t manage to find sympathy for any of the characters. Otherwise, a worthy and laudable and virtuous and dull film.

Amores Perros is the best Mexican movie of the 20th century, simply a masterpiece.

Brilliant movie. up there with y tu mama, children of men, and pans labyrinth.

I liked the third story best.

I thought ‘Sin Nombre was an excellent and totally absorbing film.

I’ll be tracking down Cary’s earlier films and watching out for his future films.

Reading this, the film ‘Sin Nombre’ in particular caught my attention, it sounds really interesting.

I unequivocally recommend Pan’s Labyrinth if you profess any sort of allegiance to cinema, literature, or history. It does not disappoint at any level of audience. Great actors, convincing narration, enthralling backdrop of the Spanish civil war. Was screened to students at the school near my home, don’t understand why since it is heavy on war violence while at the same time, delicately innocent. But then again I’m partial to military drama. If you last through this one, may want to double dose with Belle Époque, another story set during the civil war of 1940s Spain. Neither will leave you in regretting the attention. Both are in Spanish. I am not preaching allegiance to any one category of film, as I have viewed several Australian titles that have left me amazed at the splendor of the outback and the characters that seek to dominate it.

This is an interesting take on Mexican Cinema! I believe this is something we need to discuss more.

While he is not Mexican but Spanish, I would like to recommend that you watch, if you haven’t already, Pedro Almodóvar’s films. My absolute faves are ‘Habla Con Ella’, ‘Volver’ and ‘La Piel Que Habito’.

I think Alejandro González Iñarritu made some of the best movies in the last 20 years, Amores Perros, Babel, Birdman, The Revenant…

Beauutiful film, Amores Perros, I actually watched it for the first time when I was super young, and I cried hahaha, tho now I watch it and I can appreciate it.

I’m currently watching Sin Nobre in my spanish class and i’m so in love with Casper (Willy).

Amazing, thought-provoking film. Very real.

While watching Sin Nombre I understood that the Production was not low budget, the Direction was awesome and the picture was gorgeously beautiful!! but the Hondurean dialog coordination was not enought….I know that the director has no power to had have it changed. There for after making my own reserach about the direction and production of Sin Nombre I found that since there is no Film Makers and no Film business at all in Central America, they have to use Mexican actors and crew members….

There is a lot in Roma, perhaps too much. Treatment of indigenous people, patriarchy and gender relations in Mexico, inequality and subjugation, master-servant dialectic, conscience appeasement by regarding adult staff as honorary children whilst keeping them in their place, the birth of student uprising in Mexico City and US financial and arms backing of vicious militias. It’s a bit confused and chaotic, which sits strangely with its very slow pace. Still, an amazing achievement, redolent of the great films of the past — so good to see in this era of cheesy horror and sci-fi, pathetic rom-coms and comic book adaptations.

I found the film far too subtle in its messaging: for much of the film we are left to watch the day-to-day family interactions, with have no dramatic momentum at all.

Sin Nobre is a very deep movie. Gives you an idea of how the Mara Salvatrucha operates and about the dangers that latinos face trying to cross over the border. The ending is pretty sad. It has a bitter sweet ending.

The only thing is that the tatoos looks to fake.

ROMA felt like a return to the kind of European cinema I grew up with, Fellini, Antonioni etc, long takes that ask you intepret the images, rather than batter you into passivity with rapid editing and whip-pans. Its mature, open-ended, warm-hearted and just lovely.

Totally agree with you there- I immediately thought of Fellini’s ‘ La Strada’ and ‘Le Notte di Cabiria’. Both films about down trodden women and both films touching optimism at the end. Roma is quite magnificent-a real achievement.

Impeccable film – perfectly constructed and lit collection of black and white moving stills. The protagonist is a saint.

Roma is not a sloppy, sentimental journey into Cuaron’s past. It is an indictment of the caste system in Mexico that he was part of growing up. Mexican lower classes were slaves to the upper middle class and wealthy oppressors. And that included him and his family. Good therapy. But still a film that left me wanting.

The Mexican oven is baking a lot of great fantastic amazing directors for the near future.

I watched María Candelaria yesterday because I wanted to better understand Dolores del Rio. I absolutely love the way she moved from silent films to the talkies and back and forth from English to Spanish.

To me there are two film categories in Mexico. The Art/Independent scene and the Mainstream Hollywood scene. You can pick which one you want to see.

Amores Perros is a cult classic for me and a small group of friends. Movie shoes how we are all connected in unpredictable ways.

Thanks for introducing me to the Mexican cinema scene.

A point of interest is that the spurt of flourishment from Mexican Cinema in the 1990s coincided with a time of significant political and social upheaval in Mexico. There is a pretty clear relation between the two, and this lens can help in watching these movies.

Thanks for a fascinating read. Looks like a whole new world of cinema waiting for me to explore. Two thumbs up!

Can’t imagine that you would have the stamina after all those Bollywood musicals.

LOL. Oh I’m sure I can squeeze in a few films, in between takes. Oh and guess who’s recently been learning to tap dance? My neighbours think I’m crazy. Putting on the Ritz!

Mexican cinema was a mandatory subject for me in Film Studies at college and I learnt a lot about amazing movies and directors. But 10 years on, it seems like it’s mostly those same directors who are most talked about.

Who should we be looking out for outside of Inarritu, Del Toro, Cuaron?

Hi Zahra, interesting essay. Thank you for shedding light on some under appreciated movies. For me, “Güeros” is also worth mentioning. A subtle comedy that follows the lives of some shiftless students in Mexico City. Definitely worth checking out if you’ve watched “Sin Nombre”, since you can appreciate the acting range of Tenoch Huerta who deftly played an alienated writer in the former and a Mara Salvatrucha leader in the latter.