Alternatives to Microtransactions in Games and Apps

Cell phones are ubiquitous these days, as are phone-based games and apps. These activities are colorful, fun, and addictive – if you have the money for an addiction, that is. Most, if not all, cell phone games, as well as some apps such as Lumosity or adult coloring books, are free but have in-app purchases. The in-app purchases are usually tied to premium content or the ability to play the “full” game.

For instance, in Jeopardy World Tour, you can play rounds for “free,” as long as you have virtual cash. To increase virtual cash, you can wait more than 24 hours for your bank to build, or you can purchase virtual premium currency with actual money. Even the best-intentioned game/app users end up engaging in microtransactions more than they mean to.

Microtransactions can be leveraged for cosmetic makeovers (no performance improvement), performance improvements (like critical upgrades or boosts), or for disabling ads.

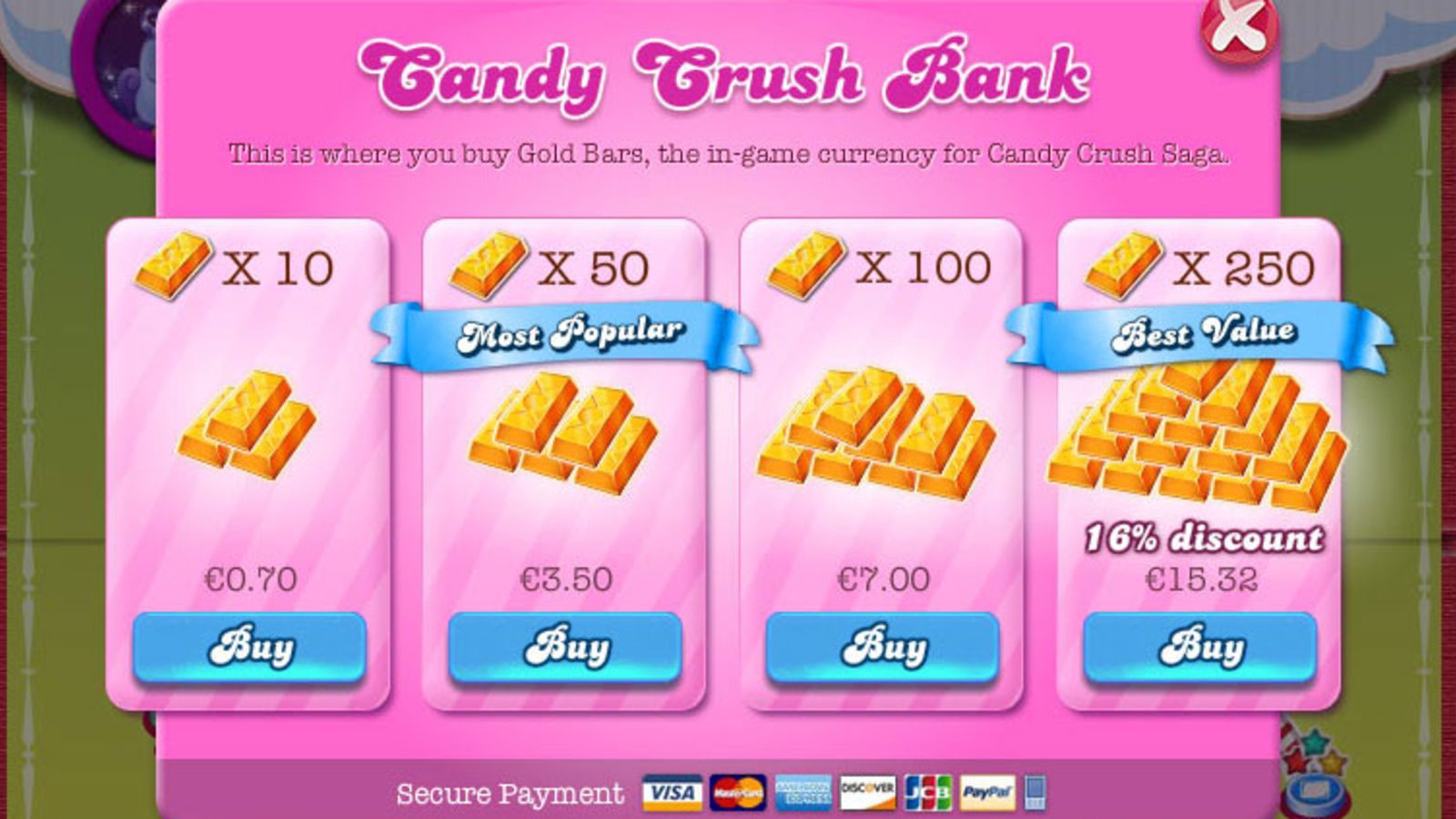

Note that in-app or in-game purchases, like the ones shown below, don’t classify as microtransactions. Microtransactions are smaller amounts, usually in cents. Some games, however, blur this line by allowing users to do both, microtransactions and larger transactions.

In many online worlds, people who spend a lot of real money actually have a nickname; they’re called “whales.” Whales or not, most players complain about microtransactions, but admit they don’t know an alternative.

Could there, or should there, be alternatives to microtransactions?

P2W vs. F2P

There are two terms used in smartphone gaming: pay-to-win or P2W and free-to-play or F2P. The gaming industry has came to realize that they can make more profits if they don’t charge money for their game (upfront) and instead, rely on microtransactions.

Sometimes, these are just cosmetic improvements like character skins, in which case the game is still reasonably competitive and fair. But in other cases, such as the notoriously P2W Rise of Kingdoms, you can purchase anything, from more troops, more commanders, and more resources to newer technologies, shorter upgrade times, faster troop healing, and so on, via the in-game currency of “Gems”, which you have to buy with real money.

The latter is an example of a P2W game.

Note that a game that has microtransactions doesn’t become P2W. When it starts rewarding players with competitive advantages for real money via those microtransactions (like buying gems and using them to get an upper hand), it becomes P2W.

A pure F2P game is free and has no microtransactions. But barely any popular game is F2P today. The reason is that implementing microtransactions is extremely easy. It’s almost like a subscription service. As even the titans of the IT world like Adobe and Microsoft have moved from one-time costs to purchase their software to a subscription model, it’s hard to imagine why games shouldn’t.

Perpetual money, in smaller amounts, is better for a company in the long term than larger amounts paid only once.

Disadvantages of P2W

P2W games favor whales

P2W games aren’t a level playing field. Some games are so tilted in favor of the whales, for example, that a new player only stands a small chance to succeed or even enjoy the game thoroughly.

I have played games where people used to spend $3,000 on a daily basis during peak events or action, such as kingdom-level war in Rise of Kingdoms that could go on for weeks or during a war league in Clash of Clans, which goes on for seven days.

When whales get an upper hand it starts to look like cheating. It also overshadows true skill and kills enjoyment.

Paying just to keep up

The worst part is that pay-to-win can quickly degenerate into pay-to-keep-up. Perhaps the best example of this is the Activision patent. Activision, a leading game studio, got a patent for microtransactions. The system, technically, is one where the game engine can suggest gear upgrades if you are match-made with players of higher skill. Instead of making matchmaking fairer, now you get suggested the items you can purchase to make up for the lack of the system’s integrity.

Nobody knows the true cost

The true cost of playing a P2W game cannot be determined. It might be easier with certain titles and all you would need is a bit of research, but for the large part, you never truly know what will your ultimate contribution be to the developer’s bank account. Games also become harder as you progress, meaning you need to invest substantially bigger amounts just to keep up with your progress rate.

Unrealistic pricing structures

Mobile games have become too adept at designing the perfect sales tactics to lure players into buying more packs, gems, chests, passes, and so on. The prices can be unrealistically high as a result. Spending $100 for a pack of gems that will last you less than a week in a mobile game isn’t really economical from any point of view. The same amount can go towards actually supporting your favorite developers in a better way.

Can there be a balanced P2W?

Game developers definitely try to balance things because if they only prioritize the whales then they will stop getting new players, in turn stagnating the progress of the game itself and stopping the creation of new whales.

That’s why the example of Clash of Clans is a good one. Supercell, the developer, balances things quite well. Though you can invest money and get an upper hand, there’s still a lot to do if you are a non-paying user. This balance differs from developer to developer and sometimes, the investors in the game decide the level of performance improvement P2W players will receive.

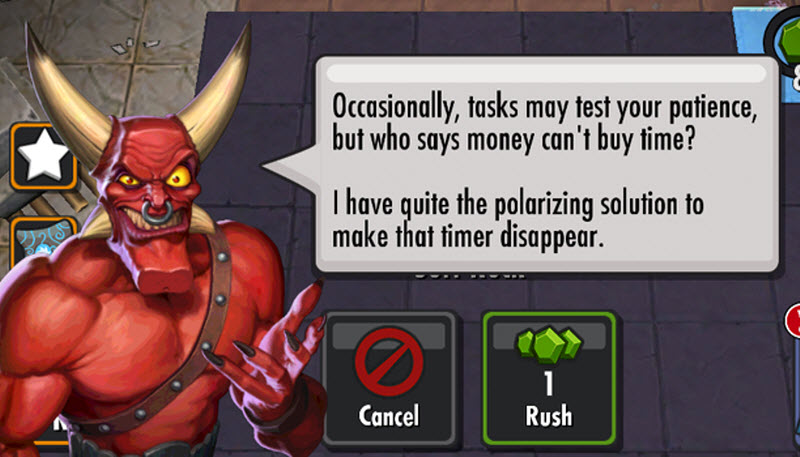

The dishonesty associated with microtransactions

Most, if not all, microtransactions are a sales ploy. More often than not, they tease you a little by giving a free item first. In other cases, they are just psychological tricks designed to dupe you into spending your money, such as an intermediate form of currency (let’s say gems) which dissociates real money from the equation, making you more prone to falling prey to such tactics.

Dishonesty is quite abundant in the case of microtransactions. Developers come up with innovative and genius ideas to force you to buy something, not help you in buying something.

A pandemic of its own, you can find tons of literature on the topic. One particularly scathing review of the “loot boxes phenomenon” is a well-articulated opinion piece by Paste Magazine writer Garrett Martin. He argues,

Loot boxes are a symbol of a larger problem at the core of the games industry, one that will continue to undermine the whole business until systemic change is enacted.

It’s also easy to see how loot boxes and similar phenomena in games can prey on people or children with addictive personalities. As the winning is not monetary, no gambling law is applied to them, but when you think about it, loot boxes or chests are truly a type of gambling.

Games can make the non-transactional route to gaining certain items, upgrades, or gear extremely time-consuming, boring, and repetitive (collectively called “grinding”). When seen as an alternative to endless grinding, microtransactions make even more sense to get a headstart on your competitors or friends.

Are there any alternatives?

Though there are games that are devoid of any microtransactions, most of the popular ones are realizing the potential earnings and moving away from a completely-free model to a microtransactions model. This means all classic games like PUBG Mobile, Mobile Legends, Pokemon Go, Call of Duty: Mobile, and even single-player ones like Subway Surfer and Angry Birds are loaded with microtransactions.

A F2P game is not really an alternative anymore. Games must make money in one way or the other in this increasingly competitive segment. So, what can be a good way out? As it turns out, there are two ways.

Cosmetic microtransactions

Microtransactions that are purely decorative or cosmetic are one of the best things. You spend to improve the look and feel, and perhaps to make other players jealous, but you gain no competitive advantage. This is truly the most holistic approach to making money from a game.

In fact, a Qutee report notes that 69% of gamers find cosmetic microtransactions acceptable.

Blockchain games

With the rising popularity of blockchain, we are seeing a newfound interest in the gaming sphere. Games built on blockchain allow users to invest their time, in-game resources, or other resources while playing the game in order to generate a currency (can be a listed cryptocurrency in some cases, for example). This currency can then be used to purchase upgrades. In this case, the user is both, making money and spending it within the game environment.

Note that the key distinction here is that although all games have an in-game currency, blockchain games have currencies or assets with value.

Given the fact that most casual gamers are generally uninitiated towards computing-related technologies, this topic will require a fair bit of background to make sense.

Many such games exist where you are rewarded with currency simply for playing more. A more optimistic aim of these games is to create a multi-game or multi-asset environment where this currency can be used interchangeably across platforms, such as other games from the same developer. In many cases, you can also trade or liquidate the currency or asset generated out of your work.

One of the downsides of these games (apart from blockchain being significantly more difficult to wrap your head around) is that they require an upfront investment to get started.

A piece of land on Sandbox, for example, costs you an upfront investment. This land (denoted by the token ticker LAND) is then tradable as an NFT (non-fungible token), which users can sell to earn money.

Similarly, in Axie Infinity, you can collect and sell collectible creatures that are a direct result of your investment of time into the game. $3.6 billion worth of trade has already happened in the Axie Infinity marketplace with the most expensive sale being of an Axie that was sold for $820,000 (rarity and stats are among the factors that decide the price).

Side note: In blockchain games, all transactions are publicly broadcast and things are remarkably more transparent about who is getting paid and how much.

It’s safe to say that if everyone can generate the money, then it’s a level playing field, as compared to games with microtransactions, which create an environment that only rewards high-spenders or whales.

Should there be alternatives to microtransactions?

Let’s conclude with the meat of the discussion. A game developer creates a game in hope of financial profits. Even free games start off free because they understand that once players are hooked, they will be willing to pay, even if it’s just a few bucks for a cool skin of their favorite character.

Consequently, it’s safe to assume that alternatives can be expected only if they still allow the developer to make profits. Purchases that don’t make the game unfair or blockchain games where you generate the money you spend are both good alternatives. The developer still makes money without tilting the game in the favor of whales in both these cases.

Apart from these alternatives and F2P games, what else do you think is a good alternative to whale-infested P2W games?

What do you think? Leave a comment.

What worries me more is the addictive nature of such games.

It is reminiscent of gambling.

You’re not wrong. Especially when you combine lootboxes AND blockchain to create an unholy love child.

The Battlefield 3 and 4 games were the best games ever and hardly any extra to pay, now the games industry has sold its soul.

My nephew is an avid strategy gamer and recently started playing a free, open-source, fan-made game called Zero K. I’m not really a gamer but it does look fun.

I have a 12 year old cousin and I have witnessed more than one fight with his parents where he is desperate to purchase the same “character skin” his pal recently bought for fortnite or some such.

Problem is, games are not just for kids. I mean I, as a 38 year old, am currently playing FF8 remastered on my switch… as well as dragon quest builders 2, spyro remastered, World of warcraft on pc and a million and three others.

Microtransactions are, sadly here to stay… and purchasing a skin, is not the same as a lootbox.. as it’s a legitimate purchase… you pay x amount you get y item. So it’s not gambling.

It’s like a kid screaming they want the item shown on TV adverts.

My daughter is having terrible time with her nine year old son, he is absolutely obsessed with these games, to the point where trying to get him to do anything else is viewed as a punishment by him, luckily his parents are also knowledgable enough about gaming, to so far prevent him from spending money on these things and are doing all they can to control him but he is not alone in this.

It looks to me as though we could be losing a whole generation of boys in particular to this toxic escapism, if we do not stop it now.

I’ve started my nerd career in early 90s on a 286 PC and have been an unrepentant enthusiastic gamer ever since.

HOWEVER…I completely and totally hate micro transactions.

Good read. There’s the dilemma that the ‘touchscreen generation’ expects everything to be free or dirt cheap. While in the day of yore it was pretty normal to spend 40 to 60 dollars on a new game, these days it should be either free or no more than 2 dollars or so. Also, technology has become more complex, expectations are higher when it comes to graphical fidelity and sound and there’s about a billion apps and games competing to be picked up for free alongside yours. So developing and publishing games is expensive and risky, while many bomb and return very little money or even make a big loss. The shakeout in the industry has been quite big over the last years.

So while there definitely is a case to be made to protect consumers from reckless spending, let’s not forget that these business models largely came to pass because the same consumers think that their entertainment should be free of charge.

Stuff that passes as acceptable today is shameful. launches of half finished products, dishonest marketing, microtransactions wherever you look…

And the kicker is the players universally hate the state of it. But the industry still makes billions because there are a handful of publisher with a virtual monopoly.

One of the only ways businesses will change their policies is for consumers to change their buying habits.

Nice work on the article, some great points in it.

I have a policy on Google Play. All games with in-app purchases automatically get rated 1 star as a matter of principle, and that’s being generous.

We all know that people who are willing to play large amounts of money on crap like candy crush are not very clever.

I think the games’ addictiveness is used to make you purchase those services. I spent a lot of money on Candy Crush before I realized that something was seriously wrong. I think the games in themselves are designed to hypnotize you and make you spend money in small amounts every now and then till you realize that you spent too much money.

If we want good quality games, somebody had to pay for it somewhere. I enjoy Candy Crush without paying a thing, up to level 70 at the moment. If some richer people want to take shortcuts and pay for the game, that is up to them. I am glad they do, as without them I would not get it for free. I still recommend it to people may of whom have gone on to pay, and are happy having done so, so it is all win/win. Everything is potentially addictive and people need to learnt to control themselves.

I don’t think this is as bad as drugs, alcohol or sex. Having said that there should perhaps be an upper limit for each player, say $50 per game.

I play a lot of freemium games on Android, but spend nothing on them.

There is a real danger when you directly monetise the addictive nature of gaming.

These games are purposefully hamstrung so that purchases become necessary if substantial progress is to be made before you die of old age (or boredom).

Games are therefore not won by skill, but by a willingness to pay for some form of booster, power-up or in-game currency. More insidious and irritating is the alternative option; simply spam your friends’ news feeds with news of the games’ existence in order to be drip-fed the required gems/coins or whatever to progress.

Under those circumstances you’re effectively doing the developer’s marketing for them! Which reduces playing to nothing more than viral advertising. What fun!

I recall a friend complaining that they couldn’t get past a certain level on Candy Crush Saga. I explained that the game was designed to make her pay up and that a good alternative would be Bejewelled 3. It costs £3.99 but has absolutely no restrictions and has a great selection of varied game modes. I knew that if she liked Candy Crush, she’d love Bejewelled 3! Her response was total incredulity: “I’m not paying £4 to play a game!”.

And that’s it in a nutshell. The model only show to highlight just how little value the average person places on video games; they’d rather play something crap for free and get fleeced once they’re invested in it, than play a well-made game for a small sum up front. As a life-long gamer, this whole approach saddens me greatly.

Most of the mobile apps making the most money are these type of games. But they’re offering an experience that doesn’t appeal to the likes of us who take our games seriously enough to rant about them on the Internet, so we look like a bigger group than we really are.

On the other hand, stats appear to show that the number of people making freemium work is a tiny proportion of those who download them – since we don’t drain server resources by not playing the games they’re probably quite happy for us not to get involved.

On the bright side, the rise of apps and the associated death of anything worth bothering with in the mobile market means I won’t bother spending a fortune to upgrade to a better telephone. So that’s some money saved.

This has killed mobile gaming stone dead for me, I’ve gone back to dedicated handhelds – they charge stupid money for their games, but at least you know the game-play has been designed to be as good a game as it can be, rather than to separate you from your cash.

The current paying model is unavoidably going to influence game design, which means gameplay is compromised for financial reasons – you’ll always run out of energy/mana/fuel/ammo in a game way before you would in a pay up front game.

The problem is that people are increasingly unwilling to pay up front for games. The price of games has been driven down relentlessly over the last decade, to the point where the typical up-front cost is $0. Even paid games get sold on for next to nothing in bundles and Steam sales.

It’s not that developers wanted that to happen, but that’s where we are at now. Nobody is actually sure of the best way to make money in this environment, and most don’t – more than 90% of game developers go out of business after releasing just one game, having failed to recoup their development costs. The median revenue for a typical game released on Steam is now less than $16,000 which is completely unsustainable.

Nobody actually knows where all this is headed, and developers will try anything to survive.

This is a function of game development having been opened up to just about everyone with the coding skills and an idea, through stream. There’s a huge amount of games being released now.

Game development is at it’s best ever. The big publishers are capable of putting an insane amount of money into their games. Smaller development teams can use crowd funding. Single talented developers can publish via steam.

These games are also designed to monitor behaviour.

The very best games were culturally (artistically) catching up to the validity and full richness of the best of film, music or literature. Then DLC-culture took hold and is now effectively breaking games on release by only releasing half the game initially, then releasing the rest in small pricey bits.

To add to the greed, a new game (which is only half-complete, remember) generally has a huge price-tag of around $60 – a new book, movie or album is far less expensive. And to justify this big price, the game’s content will feature lots of time-consuming padding so that the developers can advertise there’s a hundred hours of ‘gametime’ to be had, justifying the price. This also lessens the cultural richness a game can have (padding causing dilution of richness), putting games back behind film, music and literature in their artistic worth.

Latest example will be the remake of Final Fantasy VII. The original came out in 1997 in complete finished form, and is regarded as a cultural high point of gaming. The remake will come out incomplete, with extra content being available for those with extra cash to burn. The story will be staggered in separate full price releases, so that by the end the complete remake will cost the consumer several hundred Euros.

Greed is winning because it works. Gamers buy these games at full price, then they buy the extra content too.

An effective business model then. A booming industry. I don’t necessarily have a problem with any of that. It’s just that cultural worth isn’t the priority here. It’s a shame.

There are exceptions out there: studios that make games out of artistic passion, which are complete when they’re released, and aren’t even overpriced on Day One. Frictional Games is one such developer (known for contemporary cultural high points of gaming like Amnesia & Soma). These gatekeepers are keeping the artistic worth of games alive more than the likes of Fortnite or EA juggernauts.

However there are always review sites. If you don’t like the business model of the game then don’t buy.

You used to be able to pay a retail price for a complete product. Nowadays for retail price you get the pauper version without segments of content reserved for premium/delux/whatever editions.

Apparently my wife’s friend’s son asked permission to make some small purchases but instead spent several hundred on his online games because the card was left on the system.

Easy to password protect it.

Maybe some people shouldn’t have credit cards?

Are players more likely to be dissatisfied if they spend a large amount in one go?

There is nothing wrong with free to play games and there is nothing wrong if a gamer find a game so interesting they feel they can put some money into it.

I play free to play games often, as i have got older i have learnt to ignore impulse buys, but i often spend money if i think the game is worth it.

As someone who got hooked on Kinder Eggs and boxes of Wheetos in the 90’s I understand the devastating impact that this sort of gaming gambling can have.

From what I can tell (anecdotally), most “older” gamers like myself (e.g. late 20s and up) are vehemently against micro-transactions of any sort. The trouble is, the games industry (or at least some of the big players) are betting they can train a whole new generation to be normalised to it, and shut there ears to our protests in the hope we’ll just die out, stop playing games, or become normalised ourselves.

A friend of mine with a young son recently tried to introduce him to a game – the first thing the kid asked when he reached the first boss was where the “store” was so he could upgrade. Sad times!

Gaming has come a long way since James Pond: Robocod.

I can’t help feeling that large parts of the digital industry are Loot Boxes… the digital platform is the perfect rip-off platform…

An insightful article and judging by many of us, we can see the issues facing this generation.

Developers are of course fully aware that most of the money is coming from a small proportion of big spenders.

The worst part is that it never ends. not the game, not the spending.

What happened to games for fun. 🙂

I was playing Splatoon 2 (Nintendo, despite their faults, don’t use microtransactions in their games) when my nephew asked me if you could use real money to buy the in-game currency. I have never cringed so hard at a generation Z question in my life.

Gaming should be an escape from real life, to pay for this escape is acceptable.

Even in my city building simulation game, i had to pay to add snow.

Is that Cities Skylines? Bought it in a ps store sale recently and thought it was a bargain until I saw how much the dlc costs.

yeah, it is brilliant game, the add ons are good, but should of been built in, the mechanics are quite basic.

Gambling culture appears to have taken over the entire planet.

I think this was a great breakdown of transactions and microtransactions in mobile games! I also learned quite a bit about blockchain games, and I found it mind-boggling. Great article!

I do really miss gaming without microtransactions

I’ve heard that most people are removing themselves from technology since this crisis with technology management since 2016. The frequencies that have affected our lives are being taken control of and more than 1/2 of our world’s population is no longer here.

People are appreciating life in ways that the last few years did not allow for – and are looking for life in a way where they will not be abused.

Life is abundant, as long as we are breathing – don’t stop breathing.

Charging for a select few in-game cosmetics is a great way to both make money and satisfy the player’s need for personalisation, but there are instances which speak only to the publisher’s greed.

Valorant offers a wide variety of unique weapon skins and then presumes to demand for staggering amounts, with single skins costing at least $19.99 USD.

Prices ought to remain relevant to the level of content they provide the player.

Back in the good old days, my favourite game franchise was Skylanders. My parents could barely keep me off the Wii in the few weeks after each of the first three titles came out. It still boggles my mind how on Earth they were able to make a game that essentially charged up to AU$20 per character and somehow get that over with practically all the parents in my friend group. Now that I’m less blinded by the nostalgia I’m a bit gobsmacked at the gall they had. If they tried to leverage the same idea today I’m certain far more articles would be written about how sleazy the practice was. Or maybe not, considering Fortnite is pulling essentially the same trick by getting people to pay two-figure prices for digital skins. At least you could stick Skylanders figures on the shelf after you were done playing with them.

The correct answer to microtransactions is to hack the game file to have unlimited premium currency.

The only right solution.

It does seem like as long as a percentage of users are willing to pay money, micro-transactions aren’t about to go away. I do wonder how many people actually run into financial problems through spending money on games, relative to those who lose money gambling.

I have definitely discovered that the amount of microtransactions in games has become overwhelming these days. Every time that I play a game online, I constantly see different possibilities for microtransactions, whether it’s in a cosmetic way or not. The companies that ‘entice’ their customers by giving them free stuff/previews first are typically the worst in my opinion, as they are using tactics to persuade their customers to buy stuff.

Diablo Immortal is now one of the most notorious cases of microtransactions in gaming, as of the time of this comment. The rise of this practice really makes you miss the days of the older gens- you bought a game, you brought it home, you put it in your console, and you were playing. I totally respect that the times and techs have changed and we’re in the era of live service, day one patch downloads and DLC… but, I think that both developers and corporations need to be mindful of how harmful microtransactions can be. Just because it’s possible, doesn’t mean it’s a good idea.

Although I feel uncomfortable with one-sentence paragraphs in analytical essays, I found this piece very well thought and argued. This topic is a reflection of the way profiting is changing along with new technologies.