Using Musical Theater as a Literary Muse

Creative writing often goes hand in hand with other artistic pursuits. Some authors are also illustrators, or work closely with aspiring or professional illustrators to bring characters to life. Some writers play instruments, finding the physicality of that pursuit gives their written word deeper dimensions. Still others, this writer included, find alternate creative outlets in singing and theater.

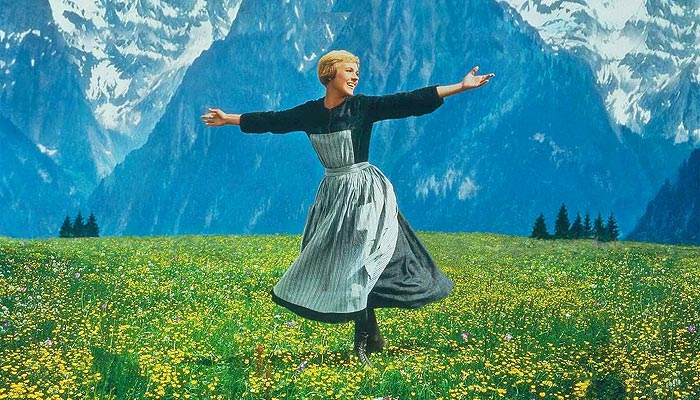

I have loved theater and show tunes almost as long as I have loved writing. I performed Rodgers and Hammerstein numbers at elementary school talent shows, and memorized musicals to the point of quoting characters’ dialogue. Currently, my iPod’s Broadway playlist is 84 songs strong and likely to expand. I have never performed a lead or supporting role onstage but always participated in musical theater when I could, and still dream of performing.

Why am I, and other writers, so drawn to musical theater? In my case, it’s because I see how well characters tell their stories through song. As a published author, I have often wished I had the talent as a musician and lyricist to place my own characters in musicals. Failing that, I’ve found that thinking of a fiction project in terms of musical theater can help me focus, craft the story as well as possible, and deal with some less-than-glamorous parts of the writing life. Using tips and tricks from musicals and their characters might help other writers do these things, too.

Start With a Few of Your Favorite Things

The first musical I was exposed to, The Sound of Music, is still a favorite, and the first number I learned to sing from it was “My Favorite Things.” Like the Von Trapp children, I used the song to cheer myself up and calm my fears as a kid. As a writer, I find there is a hidden gem in the song’s concept.

As you write, you’ll find many people will give you advice. Some of it is standard, such as, “Write what you know,” which has become standard because in many cases, it works. Writing what you know will lend your work a sense of credibility. Other advice may be more specific to you, such as what you should or should not write and who your audience should be. For instance, I was recently told I should not write a book in which a legally blind, futuristic character has to deal with the possibility of being killed because “it sends the message that disabled people should be eliminated” and “it could cause great harm to people.” I had told my detractor that I myself have a disability with a visual component, yet their comments stood.

There are, of course, rules writers should follow; if you are not a minority yourself and want to write a character who is, it’s best, for instance, to spend time talking to people in your character’s group and researching first. However, keep in mind that if we all only wrote what we knew, we’d only read thinly disguised autobiographies. If you never write about your favorite things–that is, the ideas and genres about which you are passionate–you will quickly lose your passion. Of course, none of us can write in our favorite genres or about our favorite subjects all the time, but it’s good for you to find ways to do it whenever possible.

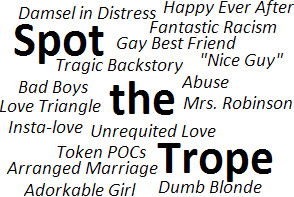

Take inventory of yourself as a writer. Note the genres you read the most and the character types you gravitate toward. If you like certain tropes, such as the couple that starts out as friends or enemies but becomes lovers, use them. Consider new angles for those tropes, or mixing a well-known trope with a lesser-known one. Probe your experiences; which activities did or do you enjoy most? Which memories are dearest to you? Those often provide clues to what your plot will be about. For instance, if you enjoy children, maybe your protagonist is a teacher, pediatrician, or childcare professional. If you grew up in a military family, you could use that background in a thriller, historical novel, or contemporary piece with a military protagonist.

Check the “I Want” Songs

The “I Want” song is a crucial piece of any musical. As the name implies, it tells us what the person singing it wants most. From Annie’s ballad “Maybe” to Alexander Hamilton’s “My Shot,” an “I Want” song encapsulates what motivates characters and why the audience should care in a span of a few minutes. The best “I Want” songs don’t have to be long ones, either. A personal favorite is Belle’s Reprise from Beauty and the Beast, because while the song “Belle” tells us who she is, it’s through the eyes of the townspeople. The reprise takes that and lets Belle speak for herself, letting us know she is more than the odd bookworm who doesn’t fit into her provincial town.

In a short story, novel, or other fiction piece, your characters probably won’t sing about what they want. Nor will they often tell us their motivations in “I want” statements. But when listening to an “I Want” song for inspiration, don’t over-focus on those words. Listen to how the characters are describing what they want, especially when they don’t use those words. Alexander Hamilton, for instance, describes himself and his situation thus: “I’m a diamond in the rough/a shiny piece of coal trying to reach my goal/my power of speech unimpeachable.” He goes on to say that he’s “young, scrappy, and hungry” like a burgeoning America. Combine this with the refrain, “I’m not throwing away my shot,” and you have a sense of who Alexander is on the inside. He’s impoverished and underestimated, but also intelligent, determined, and courageous to the point of cockiness. He refuses to let victimization or lack become his legacy.

When crafting your protagonist, ask what he or she wants, too. Ask yourself, how would he or she encapsulate desires and motivations in a few sentences? Why is it important for your protagonist to get what they want; what will happen otherwise? (For example, if Alexander Hamilton doesn’t get what he wants, he may well die without a positive legacy. If Annie doesn’t get what she wants, she’ll remain an orphan physically and emotionally). Consider how internal and external forces might help or hinder your main character. It may help to try matching your character’s objectives to an existing show tune, or a few show tunes. If your character is an orphan, you might start with Annie or Hamilton, or perhaps Les Miserables.

Note that your secondary characters will have wants, too, although these are usually in relation to the main character’s wants or goals. Angelica and Eliza Schuyler have wants in relation to Alexander Hamilton. The former wants “a revolution and a revelation…a mind at work,” which makes her a great friend and sometimes foil to Alexander. She also wants to marry Alexander, which sets up a deeply personal secondary conflict. As for Eliza, she wants Hamilton himself, not just in the marital sense but in every sense. When she begs him to take a break and says, “We don’t need a legacy, we don’t need money…isn’t this enough,” viewers and listeners identify with her pain. They see that Eliza’s want is feeding Alexander’s conflict–will he choose his legacy or his family? You don’t need to go into extreme detail over every secondary character’s wants, but knowing them will help you build a deeper, more multifaceted fiction piece.

Don’t Tell Me, Show Me

In the second act of My Fair Lady, gentleman Freddy Eynsford-Hill has fallen hard for Eliza Doolittle, the flower girl cum noble English lady. No one could blame him; flower girl or lady, our heroine charms–and shocks–everyone she meets, whether she’s relating a childhood story or telling a racehorse to “move [his] bloomin’ arse!” And Freddy expresses his infatuation in epic fashion, literally standing in front of the house Eliza shares with Higgins and Pickering to sing her a love song.

In equally epic fashion, Eliza lets Freddy know she’s not impressed. “If you’re in love, show me!” she sings at him in the chorus of a song with the same title. “I’m so sick of words/I get words all day through/is that all you blighters can do?” she demands. Eliza goes on to snark about overly wordy lovers who bury their true feelings in “talk of stars burning above,” “dreams filled with desire,” and cliched metaphors surrounding “June [and] fall.” Whether they’re writers or not, by the end of the song, viewers are cheering for Eliza and wishing Freddy would shut up. But what does this gloriously sarcastic song have to show creative writers?

Once again, the answer is as simple as the song’s title. Many writers from beginners to multi-published experts often get the advice, “Don’t tell me. Show me.” In other words, never simply say a character is happy or sad or angry. Show their beaming face or their quivering lips. Show them getting angry as they grip the nearest surface to keep control, and show them losing control as their dialogue gets more pointed and staccato. Don’t simply describe the moonlit night of a romantic encounter. Show the streetlights’ reflections wavering in the water, or note how the night air enhances the nearby aromas of flower shop blooms or restaurant fare.

In addition, avoid sensory words when possible. Sensory words relate directly to the five senses–“she smelled,” “I touched,” “they saw”–and are backhanded forms of telling. Your reader will pull away from sensory words, and the story, because they know what it is to see, hear, and smell things. They do it every day. So instead of your characters note it’s raining, say something like, “Rain ran down her legs in rivulets, filling the cracks in her shoes.” With that sentence, your readers already know a few things. It’s a heavy rain, your character is not enjoying it, and for whatever reason, she doesn’t have decent shoes to protect her. This type of writing raises curiosity about characters and their situations.

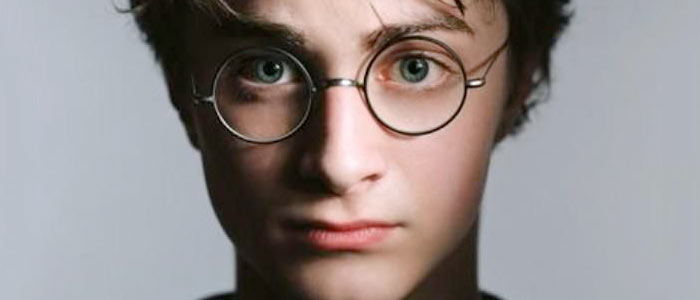

Note that some telling can be okay, depending on your genre and audience. At times, for instance, children’s authors will tell because they want to keep the language and descriptions simple, or because their main characters are series characters they want young readers to remember. J.K. Rowling, for example, often directly describes Harry Potter as a skinny kid with glasses and black hair with a tendency toward messiness. This can work for adult writing as well; Stephen King directly describes some of his settings to underline how much horrific plot elements will affect them. If you aren’t sure when to tell or show, look at sources specific to your genre. Ask yourself if your piece is more character-driven or plot-driven; that may tell you where you should spend extra time showing. Think about the POV you’re using; first-person POV often has a little more room for telling, because the character is speaking directly to the reader. However, as a general rule, readers want to be shown as much as possible.

Balance the Conflict

Another essential fiction element is conflict, but unlike the others we’ve discussed, conflict can’t be summed up in one part of a piece, or one song in a musical. Conflict must arch over the entire piece, whether it’s in a manuscript or theatrical performance. The best pieces also mix internal and external conflict well.

One of the best musical theater examples of well-balanced conflict is Fiddler on the Roof. During the show, viewers are mostly focused on the external conflict of Tevye trying to marry off his oldest three daughters. They also notice a bigger religious and political external conflict. That is, Tevye and his family are Jewish, living in a Russian Jewish village circa 1903. In terms of raw numbers, Jewish people are the majority. But the actual people in control are connected to the Russian Orthodox military and aristocracy. The Jewish people fear seeing their culture and traditions disappear, especially as the military enacts sanctions and pogroms (raids designed for injury and death) against them. When Tevye extols tradition in a prologue-type song of the same name, he’s not just talking about marital customs, cultural dress, or even religion. He’s talking about bone-deep faith and selfhood. He has to preserve not only faith, but his version of that faith, in order to please God. The best way to do so, he believes, is ensuring his daughters are married to upstanding Jewish men from the community–with the help of a traditional matchmaker who understands the need for self, religious, and cultural preservation in a hostile environment.

When Tevye’s daughters push back and marry men of their choice, Fiddler’s internal stakes get ramped up. In fact, the daughters’ journeys to love get so much focus, it’s easy to forget about the more serious externals. However, Fiddler’s writers and lyricists did a great job of mixing in an external conflict just when an internal one reaches its zenith, and vice versa. Oldest daughter Tzeitel marries her love Motel in an unexpected, yet culture-affirming ceremony, and thus finds happiness outside of strict tradition. But Russian soldiers conduct a “demonstration” on the wedding, leaving the venue in shambles and the wedding party and guests traumatized. This isn’t treated as a punishment for Tzeitel’s independence; rather, it reads as a microcosm for what can happen when both traditions and people aren’t respected at all. Later on, Tevye struggles with the external issues surrounding his home, as Jewish persecution increases and he faces the fact that he may never see middle daughter Hodel, who married a revolutionary and had to flee to Siberia, ever again. In the midst of this, youngest daughter Chava elopes with non-Jew Feyedka, breaking tradition and seemingly abandoning faith and culture in ways Tevye can’t forgive. Tevye disowns Chava because Jewish law dictates it, but grapples with that decision throughout the rest of the show, until he is able to have a quiet moment with Chava as the family is expelled from their home.

Your fiction piece may not handle the same issues as Fiddler on the Roof, nor may its aim be social commentary. Remember though, that everybody experiences external and internal conflict on some level and often at the same time. Giving your readers a balanced mix of both ensures they’ll stick with your piece because they want resolutions. The conflict and resolutions can be as simple or complex as you want; the speaker of a poem, for instance, only has a few stanzas to complete a conflict arc. The protagonist of a book aimed at young children may be flummoxed at how to get that coveted toy or cookie–but if you balance that desire with something like a requirement to eat vegetables first, your reader will sympathize with that child as much as they would for the protagonist of an adult spy thriller or historical novel.

Respond to Rejection with Confidence

You might wonder if show tunes can help you when the inevitable happens. You’ve written a lovely piece with memorable characters, tight descriptions, and balanced conflict, using a theme you’re passionate about–and it gets rejected. If show tunes can teach writers about how to hone their crafts, do they have anything to say about the writing life and how difficult it can be?

The answer is a confident “yes.” You can’t sing away the sting of rejection, at least not at first. You need to experience your emotions in reality rather than covering them up. The shock of your first rejection, or the despair of your two hundred fifty-first, is easier to bear if you call it what it is, let yourself feel the associated emotions, and reach out for support.

After the initial sting though, you may well want to channel your emotions back into some form of art, or re-experience them through the safety of fictional worlds like musicals. Sometimes, writers advise each other to pursue another art form, such as dancing, visual art, cooking, or music after a particularly hard rejection or intense writing period. As you might guess, I found this outlet in singing musical numbers and placing myself in the characters’ shoes.

Rejection is a multifaceted beast in the writer’s life. Sometimes it will make you so angry you want to throw or hit something, or call up the offending agent or editor and inform them they are the genesis of all morons. Sometimes it will make you cry buckets and question your love of writing, if not your entire calling. Sometimes you’ll be able to bounce back quickly, ready to send out your piece again, tackle revisions, or start a new project. Often, I’ve felt all these emotions and more in the same day.

The good news about rejection is, it lets you focus on any character and song type you want. If anger is your predominant response, try torch songs or passive-aggressive numbers, like “Good for You” from Dear Evan Hansen or “No Way” from Six (as in, “no way” did your rejector know what they were missing and “no way” will they bring you down for good). If you need to indulge sadness, try the eponymous “Legally Blonde” (and, if you like, pair it with the peppy remix). As your confidence and desire to write return, focus on uplifting numbers like “Go, Go, Go Joseph” from Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat or Wicked’s “Defying Gravity.” Re-focus on “I Want” songs if you need a refresher course in why you love your piece or elements of it the rejector didn’t like, such as plot or characters. Use numbers or reprises wherein characters receive encouragement, such as Cinderella’s “Impossible,” when working on revisions.

Know That “You Will Be Found”

The heartbreaking yet uplifting “You Will Be Found” from Dear Evan Hansen is arguably the most memorable and beloved number in the show. The speech Evan crafts around it is based on a lie, but writers should remember the message of being found is truth. That is, the writing life is filled with obstacles. Like Evan, you may sometimes wonder if anybody’s “waving”–that is, listening to, caring about, and resonating with what you say.

While no one, including myself, can promise everything–or anything–you write will be a bestseller, writers including myself can promise you will be found. You will encounter people who need your words, characters, themes, and ideas. In finding them, you will find the piece of yourself that is most joyful when you’ve done what you were meant to do and see it pay off. Therefore, as you write, think about who you want to find and who may find you. What do they look like, not necessarily physically but mentally, emotionally, or spiritually? What needs of theirs can you meet, that other writers cannot, or don’t meet in the way you do?

Some writers advise coming up with an Ideal Reader, and writing down who that person is or having a picture of them, either through your own art or a service like Google Images. You can be that specific, but your idea of audience can also be, “I want to write for middle grade kids.” That alone will help you narrow the style and tone of your writing. You could then specify, “I want to write for middle-grade kids who’ve had to move, or who deal with disabilities, or who live in a foreign country.” That will lead you to specify more–boys, girls, both, or neither? Does moving happen because of a loss, such as of a parent’s job, or because the protagonist is a military kid? When you say “foreign country,” do you mean a place where the protagonist’s family members live, or an ancestral home, or do you mean somewhere completely new? Will you focus on physical, cognitive, learning, or psychiatric differences?

Even when you’ve settled questions like these, you might find your audience changes because of where your piece goes, or because you find your writer’s voice is more suited to certain demographics than you thought. For instance, I began a college creative writing program convinced I wanted to write for middle grade readers, specifically girls, because I had such good memories of my favorite MG books and a desire to fill in some gaps in the genre. However, more than one professor informed me my young characters sounded more like young adults, and that my attempts at authentic teen speech were stilted. My audience had to shift to young adults and adults.

If this happens, don’t think of it as a failure to reach a chosen audience. The more I wrote and learned, the more I understood why I wrote the way I did–namely, because I had been forced to grow up fast, had always been a bookworm, and was un-diagnosed but likely on the spectrum. These realizations actually freed me up to write more authentically for the people I understood best and felt most comfortable trying to reach. Similarly, you may find that a desire to write police procedurals might not work well if you’ve never been in law enforcement or don’t have close ties to someone who is. That said, you might well be a great candidate for amateur sleuth stories, or stories in which civilians are forced to handle police matters because their world is dystopian, fantasy, or otherwise unconventional.

Additionally, don’t despair if your audience is a small niche. If you already have and love a niche, don’t feel pressured to change or expand it just to get attention or increase the likelihood of publication. Remember, Harry Potter, Hunger Games, and Dork Diaries fans were part of niche communities at first. The Chronicles of Narnia is a beloved series but still maintains a smaller-than-usual niche because of its obvious Christian allegory and unashamed bent toward young children. The American Girl and Dear America series achieved acclaim and large readership long before the Internet, streaming movies and TV, and fandoms were so much as concepts. Circling back to our musical theme, Hamilton wasn’t always a worldwide phenomenon, and plenty of “smaller” musicals, such as Six, have a broad base of vocal, loyal fans. The important thing is to find your niche, speak to an audience you care about, and let them find you.

Closing Liner Notes

It’s said writing, especially creative writing, is a solitary and lonely profession. Most writers will find this true at some point in their journeys. Often, mixing writing with another creative art or outlet helps alleviate the sense of isolation. For many writers, medium mixing can provide inspiration and guidance on honing their original craft. The melding of creative writing with the crafting and enjoyment of show tunes is only one such example, as the characters and plots of musicals help novel and short story writers encapsulate who their characters are, what they want, and what tries to stop them from getting it. Whether or not you are a musical theater fan, you can find inspiration and rejuvenation for your writing in this and any other combination of mediums.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

The “I Want” song in a musical is fairly similar to the aria in an opera, but then the musical is a development from the operetta (e.g. Gilbert & Sullivan, Pirates of Penzance), which itself developed from opera. All the same, I’ve been in musicals myself (one of which was Sound of Music), so this was fun. Good job!

Musical theatre is an artform which deserves to be taken far more seriously than it is by those who cannot consider anything outside of a narrow vein of conceptual performance or inclusive applied arts as deserving of subsidy. High end skills and production values deserve significant investment.

When I used to do musical theatre in middle school the same 3 or 4 people would get the lead roles every. Single. Year. Even after the teacher in charge made a rule that you could only get cast as a lead once she STILL cast the exact same people every single year and all of them were tone deaf with two left feet.

Like I’m not saying I was a flawless singer (because little 12-14 year old me was far from being an Idina Menzel) but at least I could stay on tune and didn’t constantly trip over my own feet or forget the moves in the middle of a performance and just freeze or forget my lines and just start riffing completely out of character. Like I worked my ass off and actually took it seriously because I genuinely loved performing (unlike the others who got cast as the leads who actually openly said they were only doing it to pad their high school applications) and the only time I even got close to being a lead was when I played Patty Simcox in Grease (which totally isn’t a lead but apparently was enough of a lead for the director to count it in her stupid “one lead per person” rule so I was stuck back in the chorus or with a non-speaking role the entire rest of my time there). All of that (plus some other bs in high school that I won’t get into) was enough to make me never want to do theatre again no matter how much I loved it and how happy being on stage made me. It just wasn’t worth it.

My deepest sympathies. I’ve been there, for other reasons (you might check out my answer to another comment below). IMHO, theater arts should be one of the most welcoming and inclusive activities you can offer to someone. But egos, traditions, stereotypes, etc. still get in the way.

The principal’s son always got the lead.

It annoys me how musical theatre generally isn’t as inclusive as straight acting, I’m legally blind and I always felt like people assumed less of me because of my disability, I understand because I’m legally blind I might take a little bit longer to pick up choreography but I even felt that way when I was just singing, I feel like all areas of the performing arts have a long way to go with inclusivity but I definitely felt much more accepted and valued for my talents when I started straight acting rather than just being seen as a liability in musical theatre, but this is just based on my own experience, I hope other people have had better experiences with this

My soul sister! I completely understand. I have cerebral palsy, and while it’s mild (I am ambulatory, have all my senses, and have a gifted IQ), it did affect my ability to dance, judge where I was onstage/in space, etc. So, even though my director called my acting ability good or even phenomenal, I was only ever given walk-on roles. Modifications were not considered; I was just pulled out if I couldn’t do something. Yet, the director would, say, let a white girl play a Latina character, let girls play guys, etc. Her justification was probably that, “Leads/supporters have to dance,” but the chorus line–where she always put me–had “dance” as like, 100% of their reason for being there. I loved theater and still do, so I kept trying. And I never spoke up because, other than foreign language, chorus and theater were the only two electives my school had that I could do. I was afraid if I protested, the teacher/director would kick me out. But looking back, I wish I had challenged the whole setup.

I have a friend who is no dancer, nor a singer, but she is an INCREDIBLE actor. Therefore, she’s able to pursue dramas and plays instead!!

Theatre must go open air again, or simply hit the dirty streets of London, burlesque and all.

Musical theatre is one genre that I have to have an emotional connection to to actually enjoy. Shows I’ve seen have songs I enjoy the most (probably due to exposure bias, but there are shows I have seen that I haven’t particularly enjoyed the music from). One show in particular, The Band’s Visit has some incredibly beautiful pieces that moved me to tears. I literally cried for the first time in years when I saw that show. The soundtrack was something I listened to on loop for weeks after seeing it, and I still listen to it every once in a while nowadays.

Musicals feels totally weird. 🙂

What do people thing about musical movies?

Spontaneous singing breaks the fourth wall. This breaks immersion and takes me out of the movie.

I think this is the most common reason people don’t like musicals.

As a lover of musicals, no offense here, I think people just aren’t “getting it” or seeing it for what it is. The characters aren’t singing. It’s just a storytelling convention. Like a soliloquy in classic theatre. The character Hamlet isn’t walking around talking to himself, the soliloquy is just a convention for giving us access to his thoughts (essentially the pre-film version of a voice-over). Same deal for the singing in a musical.

I don’t really think it does break the fourth wall. Movies create their own reality, wherein the rules that the characters follow are not necessarily the rules that we in our world follow. Personally, I think that if the spontaneous singing fits with the rest of the movie, then it doesn’t matter if it doesn’t fit with real life. I get that not everyone is gonna have the same views on this but I think that if we can suspend our disbelief for superheroes and science fiction, we can suspend our disbelief for spontaneous singing.

Phantom and Les Miz are the big two musicals that work for me. Pitch Perfect is literally pulling teeth because I strongly dislike the only mouth band where people just use their mouths instead of instruments.

They’re just boring as hell to me. All of them. One moment you’re watching a movie, One moment later they all swinging along jumping on tables. It’s jarring, and breaks the immersion

Pitch Perfect isn’t a musical, just a movie about people singing with musical performances in it.

I adore a great musical film. Baz Luhrmann’s “Moulin Rouge” is still one of my all-time favorites, and “The Greatest Showman” is ‘spectacular.’ When done well, I think the heightened artifice of song and dance complements the medium really well.

I’m a big fan of them myself. Obviously there are crappy ones, but that’s true of any genre. I don’t think people give musicals enough of a fair shake, more so than with any other genre.

You know the phrase, “I liked musical theater before it was cool?” Yeah, that was me.

Musicals are amazing. I hate the excuse “it’s not realistic!”

I love musical when it’s in animated form (because suspension of belief has already occurred the second I chose to buy a ticket) and for movies like Dreamgirls where most of the songs are performances (didn’t like that movie, either though).

Animated musicals are really cool, especially the ones from Disney that have gotten Broadway shows. I often end up liking the Broadway versions even better too, because they expand on characters and backstories, and because they add new songs.

There’s a wide aesthetic divide between musical theater and the rest of performing arts to my ears, it’s hard to describe as anything other than “musical theater is insanely corny” but that’s what it comes down to a lot of the time. It’s a kind of performance I see as having little aesthetic or cultural value but I’m also a huge snob.

This article is a guilty pleasure, just like the art form!

If people really want to give musical theater a shot, I would say try Reefer Madness. It’s really funny, it gives the actors what they desire most in life: an excuse to waaaaay over act, and the subject matter is weed so no one is taking themselves super serious. There are a lot of more recent shows that are really genuinely funny.

It’s good to read this. Musicals are performed in the main by extraordinarily able people trained to a very high level.

Very well done. I teach musical theatre in middle school and plan to show this article to them for our musical history unit.

My friend is visually impaired and she feels so left out because she loves theater songs but she can’t preform in them I just feel really bad for her.

I like old musical, but probably the last one I liked was Annie in the mid 80’s. Since then, I don’t think Hollywood has done musicals well. I’m not sure what it is. Maybe the music just isn’t as good. I can’t really explain it but modern musicals usually feel pretentious. From the 30’s to the 80’s musicals were fun and made for the masses. Now they feel like they are made for a special audience of musical fans.

I think in recent years filmmakers have been borderline ashamed that they’re making musicals. Especially when doing Broadway adaptations; they want the built in audience that the stage show has, but they don’t want to make something theatrical or flamboyant, and they want it to “make sense” that the characters are singing. Sometimes this works, like in Cabaret or Chicago, but more often it doesn’t, like with Nine or Into the Woods.

I love musicals…on broadway and on stage in general. Film musicals seldom create the atmosphere I like to feel and do feel in the theatre, concert hall, or wherever. Also, I find the singing to be vastly superior when done by the stars of my favorite musicals. These are often world class baritones, tenors, sopranos, etc. Don’t get me wrong I like Phantom (the movie) a lot and Emmy Rossum is an amazing singer, but Gerard Butler has no fucking business playing that part. I’ve seen high schoolers perform that role better than he did. Just as I feel a legit movie deserves top notch acting, I also feel that a musical deserves top notch singing.

As someone who studied theatre and works as a stagehand…I’ve never cared that much about musicals. Some of them are really great, some of them are terrible, but on average, they have the same problem action movies have, which is that they’re primarily about the spectacle of theatre, and are pretty vapid underneath the choreographed dance numbers. But those sell tickets, not heady Brecht plays, so I understand why they’re popular.

That’s to say nothing of the culture around musical theatre nerds, who are all uniformally petty Disney freaks who randomly burst out into song and bitch about how much better they could have done in the lead role. No thanks, I’d much rather hang out with all the chainsmoking, shit-talking carpenters, riggers, and electricians than listen to some swish try and fail to hit that “aaaaAAAAaaaah” note from Wicked for the billionth time.

I enjoy musicals. I get entertainment out of them. They are a fun experience for me. Well, some of them. For me, there are good musicals and bad musicals, because the general field really works for me.

I wasn’t really into musicals, but I came across one on YouTube called “Firebringer” produced by Team Starkid. What I like about them is that they are comic musicals, and don’t take themselves too seriously. “Firebringer” and “Twisted” are both great musicals from them. Much like music and movies, there are different genres.

Many do seem to think that all musicals are somewhat the same, but there is actually a huge variety of different subgenres. To name just a few interesting, more unconventional ones in musical FILMS are: Dancer in the Dark (pretty much an anti-musical), The Lure, Lisztomania, The Rocky Horror Picture Show, Anna and the Apocalypse, The Happiness of the Katakuris, Repo! The Genetic Opera, Cannibal! The Musical, Head, Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band

I am a regular theatre goer but have no interest at all in musicals, don’t even read reviews of them.

This is an awesome article. I’m sharing this with college students next week in a lecture. 🙂

I love MT, but directors just giving the older kids in my school chances that I (and my fellow 5th graders) don’t get like a main role they are on there not even caring when we audition but then the older kids go there they give them respect that we didn’t get. That.

I love progressive music and music that tells a story. I also love big sound stages, especially with orchestra and maybe choir bits. I find myself only liking some songs from musicals.

In most music, even prog groups, the vocals are a fairly even partnership with the instrumentals. In musicals it’s generally much more important that people are able to get all the vocals on first listen, as they’re integral to the understanding of the story. Therefore, the quality of the sound sometimes takes a backseat in exchange for easier listen-ability.

That said, there are some songs from musicals that are flat-out amazing. Seeing You from the musical Groundhog Day is actually my favorite song (period, not just from musicals). It very much depends on the purpose of the song, and of course who wrote/arranged it.

Musical theater is not just less miserable and fiddler on the roof or some shit. I thought it was all gonna be lame as hell going in, but some of its really good.

I saw Richard E. Grant as Henry Higgins in My Fair Lady. Outstanding singing and choreography. Not big on musicals in general, but that was a lot of fun.

I liked reading your article, but I can’t stand when people randomly break out into song during scenes that don’t call for a song. It doesn’t make any sense, and it annoys the hell out of me.

Why are musical theater so campy?

I’m not sure what “campy” means. If it means “cheesy and over the top,” maybe it’s because the producers/directors are trying to achieve a form of escapism or idealized life that we will never have, but can enjoy watching.

I think the campiness is the product of an echo chamber from the past 30-40 years. People who want campy are attracted to the theatre and so shows are made more campy to fill seats, rinse and repeat for generations.

The longer I’m in this industry the more reasons I find to be annoyed by it. I love musicals so much, but the industry?? Nope nope nope lol

I’m not a huge fan of the industry either, mostly because of how they think only certain people are worthy to participate, how they idealize only certain types of bodies, etc.

Great article! On the topic of converting stage musicals to film – which do you think has been the most successful?

I’m really looking forward to In The Heights this year.

Musicals are hackneyed and campy and overblown and bombastic. What not to like!

There’s some real artistry and hard work and beauty in great musicals and I hate to see that go to waste because baseless stereotypes about musicals are so prevalent and they make people avoid them.

I use musical theatre to educate adults with disabilities.

Good post. I enjoyed Walk The line, Jersey Boys and Ray.

I can’t stand musicals like west side story, but really enjoyed chicago and little shop of horrors.

As a lover of musicals and aspiring writer, I really enjoyed your article. I agree that theater can help bring direction and tone to your own writing, and that you can even use skills that directors use for your own benefit. The line where you talk about, as a writer, how you should use your own experiences to bring something new and interesting to the table and try to connect with the people who will find your story was a strong hitter for me. I often find myself trying to come up with new engaging versions of things that already exist, but why not add a bit of my own personal experience to a story to allow people, like myself, to be seen. Thank you for writing this 🙂

It’s important to maintain conversations about musical theater, especially nowadays because it’s the medium being most disrupted by the pandemic. A lot of conversation about musical theater gets drowned out by stereotypes and negative experiences associated with it. Most people associate MT with large scale, skin deep theming, and heavy handed motifs, but that’s an unfair generalization seeing that many impactful musicals are small in scale and complex in thematic weight (Preludes and Falsettos spring to mind.)

With every other art form, musical theater has its own strengths, its own methods, its own points to make. The most effective musicals are the ones that understand this, and use music to tell their stories in unique ways. Hamilton is the obvious example, using contemporary musical stylings to tell an old story in a unique way. Another example is Preludes again, which uses Rachmaninoff’s music to tell a very modern feeling story about writer’s block and self doubt. It even goes a step further to have tunes inspired or suggested by Rachmaninoff’s music, with traditional songs, monologues set to music, and some more unconventional avant grade pieces.

Most people have negative feelings about MT, probably due to bad high school experiences or the infernal group of annoying condescending theater kids. This too is unique to musical theater, for no other art form has such a “have and have nots” mentality on the ground social level. It’s important to remember that in search of identity while growing up, it’s easy to shun or disallow because it’s a simple way to feel special. Then when people feel unwelcome or forced out, it’s quicker to hate than to understand. The point being that musical theater is such an important and specific way of expressing ideas that a lot people forget the nuances and uniqueness that musical theater has. Nuances that can help any form of writing, or creativity. One can get inspiration from literally anywhere, and musical theater is no different.

I feel as though I have found my soulmate! I have loved musicals since a very young age. Falling in love with the music of “Rent” in elementary school to graduating high school loving “Hamilton.” My love for musical theatre has enhanced my writing experience. The music itself keeping me focused on my writing but also being able to tell a story through music was always absolutely inspiring to me.

Growing up in NY, musical theater and Broadway have always hit close to home. Good job!!

I don’t see nearly as much musical theatre as I should. I do like modern musical film, however. Moulin Rouge, La La Land. I love music and don’t often see the kinds of music I gravitate towards end up on screen (or the stage!). Maybe I should write one?

great essay

nice

Interesting!

As someone who studied music and now wants to pursue writing, and has felt confused ever since about how to mediate the two art forms, this article has given me much hope! Not only am I more inspired to takes notes and apply lessons from different art forms to writing, your article has been incredibly informative in *how* exactly I could frame that learning and apply it to narrative fiction. Amazing content and a well-structured article. I’ve always been interested in how the “pure” musical aspects of numbers in musical theatre have communicated the unspoken feelings of the characters, thereby guiding the understanding of the audience as well i.e. like when a familiar theme sounds in the background. Very Wagner ‘leitmotif’ ! Also agree musical theatre definitely deserves much more attention as both a musical and storytelling form.

I think your comment just made my day. Trust me, I needed that. Glad I could help.