Norman Rockwell around the Christmas Tree: Maturity, Sexuality and Santa

Norman Rockwell is often valorised as the producer of idealised Americana, producing kitschy images of comic and sentimental value. However, beneath the cheesy and sweet veneer lies a less innocent world. Often, Rockwell works to invert or satirise stereotypes of serious adults and pure children. Particularly, his depictions of children uncovering the falsity of Santa costumes, exudes a notion of maturity and disillusionment. However, in two examples of such works, The Discovery and Santa’s Surprise, Rockwell gives the viewer the perspective of an adult and child respectively. This shows how different generations react to the discovery of truth and maturity, implying the adults panic like children while children see the truth with a positive sense of self.

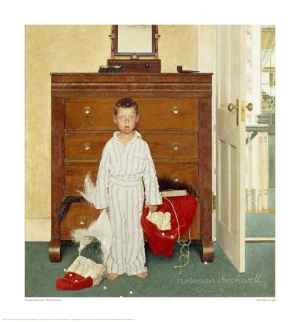

In The Discovery, we see a young boy’s demythologising of Father Christmas through the eyes of his father. The composition illustrates the boys emergence into the world of adult reality and his father’s, and our, dismayed response to such a personal event. Here, Rockwell shows a child wearing pyjamas, opening his father’s drawers and pulling out a Santa suit with a surprised expression on his face. Also, there is string dangling and unravelling from the bureau. This manifests as a reversal of opening presents on a Christmas morn. Adding to the scene are white, spherical and toxic mothballs that are strewn across the coldly blue carpet, becoming a morbid and pathetic substitution of traditional snow. In addition, the father has left his “pipe on the dresser – just like Santa would leave his pipe behind in a story of Christmas morning” (Starr). Consequently, we can see the image as a parodic inversion of a Christmas morning, with the revelation of the respective identities of both the father and Santa seen as a gift to the child: The present of maturity and access to the seriousness of adulthood. Arguably a present the adult believes opened before its due time.

Encouraging such a perspective, the artificial flowers of the wallpaper are contrasted with the real foliage of the plant in the far background. This increases the notion of artifice being undone and revealing the reality of the world. In fact, material and artificial culture is usurped by the natural and organic. Christmas is not about objects and presents but about real people, life and personal growth.

Yet this is not seen as an easy and enjoyable transition. The exaggerated and melodramatic look of shock on the boys face emphasises his feelings of betrayal and sadness. But it is not merely the child who feels oppressed, as the constant, direct and exaggerated stare of the small boy makes the viewer feel uncomfortable and “slightly exhausted” (Chevalier). We feel as traumatised as the child. In fact, the asymmetrical positioning of objects and subjects within the illustration imbue a sense of discord visually. For example, the young boy is slightly to the right of the middle of the chest of drawers and the chest of drawers is slightly rightwards of the painting’s centre. This asymmetry denies any sense of harmony and control, instead implying that this entire event has been quite traumatic and destructive for both the child and the adult witnessing the event.

So destructive in fact, that notions of identity itself are disrupted. The mirror atop the drawers is left blank, depicting only the wall’s reflection. This is an example of how “Rockwell’s images provoke the viewing self both to acknowledge and deny what it sees, thus disjoining into multiple selves” (Halpern, x). Hence, the lack of depiction demonstrates the parent’s desire not to be in this awkward moment. Simultaneously, it conveys how the paternal existence as a role-model and authority-figure is compromised, with the unreflective mirror implying how the parent’s identity is left indeterminate to the child after the recent discovery. Implying that the adult must engage with the child to gain some sense of control and power back.

This image is not merely traumatic in the sense of familial identity, but of sexual identity also, as there is an undercurrent of developing adulthood and masculinity in this seemingly sentimental image. For instance, the boy himself wears pyjamas that are too big, clothes he will grow into, emphasising an emerging sense of maturity and masculinity. The discovery of the costume forces the child to enter the adult universe of lies and deceit. However, this is not merely a discovery about reality and fiction, but “a sexual one, represented by the adult, wiry hair that the Santa suit contains in abundance” (Halpern, 169). Importantly, this sexual maturity is subversively associated with transgression against the privacy and primacy of paternal order. This is because the child has been curiously and illicitly rummaging through his father’s bureau in the bedroom. Amplifying this sense of misbehaviour, the vertical stripes of the pyjamas juxtapose with the horizontal planes of the carpet and drawers. This achieves a feeling of conflict and disorder, making the child be seen as out of position and in the incorrect place. Overall, a typical Freudian reading would read this as the Oedipal desire to kill and replace the father, destroying his suppressive ‘egotistical’ order and unleashing the boy’s own sexual potency. These sexual undertones simply add to the discomfort of the parental gaze, refusing to acknowledge the threatening and growing manhood of the child before them.

Truly, there is a feeling of diversion and distraction within the picture that implies a refusal to engage with the child. Importantly, the photographed and modelled bedroom that preoccupies the work is in direct contrast to ‘the staircase and the rooms leading away from it [that] were not there at all’ (Scholes, 96). Thus, it can be said that the background is an imagined and unreal place from the mind of both the artist and the observing character whose perspective we occupy. Arguably, then, the rooms to the right become a flight of fanciful escape from the disastrous event in front of us. Exaggerating this, there are several diagonals that go from left to right, low to high, foreground to background. This includes the Santa suit dangling out from the drawer, the banister in the landing and the curtain in the far room. Consequently, these angular objects direct the viewer’s eye, and therefore mind, outside of the room and away from the difficult situation. Indeed, the only instances of red in the painting are the festive costume at the centre and the distant vase at the border. Such visual rhyming serves to direct the eye away from the child. Overall, then, the parental gaze gives way to a childish desire to escape the confrontation and the acceptance of responsibility that comes with it.

However, a feeling of claustrophobia counteracts this feeling of liberation and releif. The exit from one room is undermined as simply an entrance to another room; the perspective from the window merely provides a view of the side of another house. Thus, freedom from liability is impossible. Indeed, the adult is reminded of their place in a family home and their position in a community. Surely, the viewer also feels manipulated and constrained into becoming a character in this narrative situation by Rockwell. Any notion of taking flight is denied, reaffirming the parent to accept culpability for their manipulation of both the child and the holiday season in general.

Resultantly, The Discovery demonstrates how adults exhibit a distinctly ‘unadult’ anxiety and surprise about the inevitable maturity and disbelief of their children. It conveys how parents and elders should accept the destructive or positive consequences of their actions and not feel dismayed about the collapse of their annual fabrications.

In contrast, Santa’s Surprise can be said to convey the child’s point of view, which shows the revelation to be a beneficial symbol of growth and adulthood. It depicts a young girl walking through a doorway only to witness her mother dress her father as Santa Claus.

Like The Discovery, understanding the reality of Christmas is seen as a step on the road to maturity. The child in the mirror is placed at the relative top of the geometrical triangle, which is formed by the presents, characters and the chair arranged in height order. This provides her with increased adult-status and positioning above or alongside that of the parents in the picture. Developing this idea, inside the ornate perimeter of the mirror we can also perceive the corner of a picture frame and the outline of a doorframe. These multiple borders constitute images-inside-images, which draws attention to the artifice of both the work itself and the adult world, denoting the emerging self-awareness of the young girl. Generally, this reveals the sense of increased maturity from the girl resulting from her unveiling of Christmas.

Once again, growing adulthood begets awakening sexuality in Rockwell’s painting. Here, the doll appears to wear a dark teal and white outfit that is similar to the mother’s own clothing. In fact, they are also positioned facing in the same direction. Therefore, we can see motherhood as an idolised role that female children, like the girl in the image, are indoctrinated into through toys. Such sanctified imagery is undermined by the sexual position of the mother on her knees, with in with the upright and phallic pillow protruding from the father’s trousers. Yet, paternal control and male sexuality is depicted through a shrivelling mask, a limp pillow and a dangling hat. This allows female agency and sensuality to be freed in the child’s maturity. Also, the mother is seen as active, stitching the helpless and dishevelled father’s clothes. Thus, the toy’s inanimate and saintly figure of the mother gives way to the reality of a pragmatic and sexual person through this conjunction of images. Overall, then, the child perceives her entrance into womanhood as positive, realistic and assertive.

Rockwell’s picture once again has a strong theme of innocence lost, of which varieties of whiteness are emblematic. If this white and vague scenery is meant to imply innocence and purity, it is a saintliness that is emphatically contrasted with the brightly colourful foreground and characters. This demonstrates the relative garishness and apparent vulgarity of the adult world. However, as the walls and carpet are illustrated only through straight, black lines, the innocent world is seen as constructed, empty and bland. Furthermore, the white background emphasises the central action with little distraction, it is an example of “an empty world […] meant to be ignored or disavowed” (Halpern, 75), illustrating the child’s questioning and emotional willingness to become involved with the scenario in front of her and us. Subsequently, Rockwell uses the vacant backdrop to convey how the child perceives their admission into adulthood as something relatively exciting and liberating from the imposed naivety of childhood.

Hence, we can see how Santa’s Surprise reveals that children gain a productive sense of agency, self-awareness and sexuality from seeing the facts behind Christmas. By placing the viewer in the child’s perspective and presenting a more symbolically positive image, Rockwell reassures us that our children can cope with the revelation in a positive and character-building manner.

Accordingly, Rockwell’s depictions of Santa can be seen to vary depending on whose perspective he gives us. Adults are forced to confront responsibility while children are happy to do so. Overall, he uses sexual symbolism, composition and colour to suggest that truth and reality are necessary for the development of children and that such veracities are nothing to worry about. Ergo, if you are ever putting up your Christmas tree and wondering what this spectacle is doing to society’s future generations, you should just relax and remember that they can handle the truth.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Much of Norman Rockwell’s work are familiar to many of us, but to some of us, they really are personal with nostalgia all around.

I never grew up with any knowledge of Rockwell, although I can relate to their idealism at times. Thus, when some people see his pictures as pure sentimentality, I tend to look at them bit more analytically. Maybe TOO seriously though! 😛

GREAT article! Whenever we think about Holidays, thanksgiving, Christmas… we always tend to want to pictures ours to be as complete, perfect, as joyful as one of Rockwell’s paintings. They never are, of course, but we can still try.

I think Rockwell is showing us that Christmas can never be utterly illusory and perfect, and that all those imperfections and revelations are essential to our entrance into the adult world. 🙂

Besides, the idea of everything being overly happy and overtly perfect creeps me out a bit :S

I grew up with Rockwell via his covers in Saturday Evening Post and did not think of him as an artist for example in the sense of Van Gogh or Rembrandt – just a great illustrator. During 1972 in Washington DC, there was an exhibit of his paintings at the Corcoran Gallery of Art, and my feelins about Normal Rockwell changed completely. The Four Freedoms is timeless, the little girl walking to school surrounded by ?? National Guardsmen spoke eloquently of America in the 1950’s. A picture truly can say a thousand words; Rockwell captured earlier 20th century America beautifully.

We might have seen more overtly political art from Rockwell if the editors at The Post and other magazines hadn’t stifled certain elements of his work. Indeed, the audience and staff didn’t want to see the controversial elements of America or its disenfranchised minorities, so it often demanded more sentimental images.

Rockwell was such a talented artist whose work defined a generation of Americans.

Part of the reason he could define a generation was the media he worked in: He illustrated magazines, book covers, calendars, booklets, catalogues, posters, sheet music, stamps, playing cards, murals. The industrial system and consumerist ethos were essential to the content of his works as well as the proliferation of his art or fame.

Norman Rockwell has been included in my cultural discussions in class. This analytical study would have come very handy. Very nice article.

Thank You. Personally, I found it pretty hard to find good analytical or critical discussions of Rockwell. So every little contribution to his legacy helps. 🙂 Halpern’s book is a decent study though and well worth a read.

I think it’s interesting to point out all of the sexual symbolism that may not be immediately obvious to the majority of viewers because they assume that the paintings capture a wholesome ideal of family life or childhood. The idea that the very purpose of Rockwell’s inclusion of the symbolism is to subtly reinforce that this discovery is natural and the child is more prepared than the parent assumes them to be is reassuring. Culture’s continued fascination with the artist’s work isn’t just that it capture’s a simpler time but that it conveys the loss of innocence as the change you can anticipate, something to be expected but not feared. Lovely article. Thank you for the perspective. It certainly stimulated my thinking.

Indeed, I often think that sometimes the IDEA of a Rockwell picture comes before the ACTUAL image for many viewers, preventing them from seeing the sexual symbolism and artistic arrangement that is vital to the intention of his work. Thanks for the thoughtful comment!

This is a really great piece and I think many of the same analyzations can be applied to some classic Christmas songs as well, particularly the ones about interactions with Santa Claus. Only now as an adult have I realized how disturbing many of the songs about Mom kissing Santa under the tree have sexualized a situation that is meant to show the child’s disillusionment you described. Yes, we can say maybe it’s Dad dressing up as Santa, which would be a perfectly understandable explanation. But the fact remains that the purpose of Santa’s existence is for the child, leading to complications when the parents are involved in perpetuating this fantasy but also somehow at fault when the illusion is shattered.

It’s the adults who idealise and commodify the concept of “innocence” and project it – annually – onto younger generations. And we haven’t even discussed all the complications with the Easter bunny or Tooth Fairy yet. Adults make childhood tough. Thanks for commenting.

Wow, this is absolutely splendid! You did a thorough, amazing job with this. It’s very insightful. I love when people analyze art like this. The arts articles on this site are some of the most interesting I’ve read. Thanks for the read!

Well, I’m glad you liked it, especially if it didn’t come across as TOO thorough. I think I have a tendancy to dull my rhypothetical readers sometimes… Thanks for commenting.

Awesome analysis. I too am struck by the use of mirrors in these two works of art, and am especially drawn to the mise-en-abyme type of mirror image in Santa’s Surprise. The troubling parallel between that maturing little girl’s growing self-awareness and her being “placed into abyss” (translation of mise-en-abyme) really lends credence to your point about Rockwell’s cheesy paintings belying a less-than-innocent world. These paintings remind me of certain Hollywood family melodramas of the 50s, like Bigger Than Life (1956) and All That Heaven Allows (1955) — I’d recommend them, especially if you’re into expressive use of color and kitschy veneers covering dark undercurrents.

Thanks for your insightful comment and taking the time to read this article. Next time I write an essay involving recursion I will try to include the term “mise-en-abyme” (I do enjoy using big, technical phrases: they make me feel clever!). And I will try and give those movies a watch 🙂