The Odyssey: A Father and Son Quest for Kleos

For a harrowing twenty years, Odysseus has remained absent from his son Telemachus’ life. At the beginning of the Odyssey, readers find Telemachus on the island of Ithaca, his birthplace and a kingdom void of strong, male role models. Now ravaged by suitors and in complete disarray, the kingdom suffers in Odysseus’ absence and so do its inhabitants. The suitors have clearly violated the sacred tradition of xenia, the Greek concept of hospitality and guest-host relations, as they pillage the kingdom for food, drink, weapons, and women. Amidst this physical chaos, we are introduced to Telemachus’ emotional turmoil as well. Without a clear father figure, Telemachus is seen as immature with a severe lack of confidence in his uncertain role in Ithaca.

Key Greek Terms to Know

- Xenia – the Greek concept of hospitality and guest-host relations

- Napios – disconnected

- Polytropic – complex, complicated, multifaceted, of many turns, of many ways

- Kleos – glory, a good reputation, social identity, true identity

- Nostos – homecoming, song of homecoming

- Menos – mental power

- Mentor – he who connects mentally

The Disconnected Young Man

In an interview with the Atlantic, Dr. Gregory Nagy, professor at Harvard University, describes Telemachus as “a clueless, disconnected [napios] young man who doesn’t really understand what his role in society and in life might be.” If compared to Odysseus, the bard of the epic poem then seems to present Telemachus as a foil to his father, possessing weak and undesirable characteristics in contrast to Odysseus’ sense of authoritative assurity, prowess, resourcefulness, and multifaceted [polytropic] heroism. Throughout their synchronous journeys, Telemachus becomes characteristically more Odyssean, and with Athena’s divine guidance, she draws the men closer to each other, emotionally and proximally, closer to the inevitable recognition scene in Rhapsody 16, and closer to their shared glory [kleos]: the suitors’ death.

The Unclear Pronoun

As early as Rhapsody 1, Athena, Greek goddess and guide, announces her intentions to lead Telemachus on a literal and figurative journey. She intends to offer encouragement and power, furthering his leadership skills and sense of duty to the kingdom. She ends her speech with: “…I will conduct him to Sparta and to sandy Pylos, and thus he will learn the return [nostos] of his dear [philos] father, if by chance he [= Telemachus] hears it, and thus may genuine glory [kleos] possess him throughout humankind” (Butler, Od. 1.93-95).

In most translations, the last line, which includes the objective personal pronoun “him,” remains ambiguous. The “him” could easily mean either Telemachus or Odysseus—most likely, both. In this one line, Athena speaks divine glory into both of the men’s lives, reconnecting father and son through kleos, and solidifying their fate. Kleos is translated as “glory” in Butler’s versions of the Odyssey; however, for better clarification on the Greek term, another translator deemed this word’s meaning to be “a good reputation” (Lattimore). Dr. James Redfield, professor at the University of Chicago, takes yet another step further with his explanation of kleos as “a specific type of social identity,” a story that “can survive his personal existence” (34). Ultimately, the revengeful act of defeating the suitors will become the kleos (glory or good reputation) that possesses both men and seals their social identity. Fatefully, this moment can only occur between father and son—two generations reunited in this final role after twenty years of separation.

Mentes, Menos, and Mentor

Further into Rhapsody 1, Athena appears to Telemachus disguised as Mentes, offering advice and setting him up for his journey to Pylos and Sparta. During this interaction, she shifts Telemachus’ mentality and focuses him in the direction of his and his father’s kleos:

“With these words owl-vision Athena went away and like a bird she flew up, but into his heart [thūmos] she [= Athena] had placed power [menos] and daring, and she had mentally connected [hupo-mnē] him with his father even more than before. He felt the change, wondered at it, and knew that the stranger had been a god, so he went straight to where the suitors were sitting” (Butler, Od. 1.319-321).

This interaction demonstrates Athena’s divine direction and her influence over Telemachus. She prepares him for his personal development and introduces the concept of menos [mental power]. Telemachus’ journey will further his leadership role, as he visits well-run kingdoms; meets positive role models, Kings Nestor and Menelaus; receives proper xenia in the form of food, gifts, and rest; and finally, hears of Odysseus’ cunning. While Telemachus listens to the stories of Odysseus’ epic adventures, Athena, now appears as Mentor (“‘he who connects mentally”), relating to our modern-day term of mentorship (Nagy). She links the young hero’s thoughts to past, present, and future timelines: the connection to his father’s legacy (past), the connection to Athena (present), and the connection to his father’s return (future).

The Goddess of Wisdom

Nagy even suggests that Athena’s guidance connects Telemachus to his ancestors, and all of these mental connections combined correlate with his newfound noble behavior:

“What Athena succeeds in doing as Mentor is connecting the thinking of the young man with the realities of the heroic legacy of not only his father, but all his ancestors, male and female. This relationship literally connects the mind of Athena with the mind of Telemachus—there is a real transfer of thought from one to the other, and that transference is embodied by Mentor. She lets him know how he can behave like a true prince. It’s a recharging of the batteries” (O’Donnell).

Throughout these experiences, with the help of Athena and his father’s friends, Telemachus’ attitude changes; he begins to see himself as worthy of the throne, and with his increased confidence, his social identity or kleos finally begins to form.

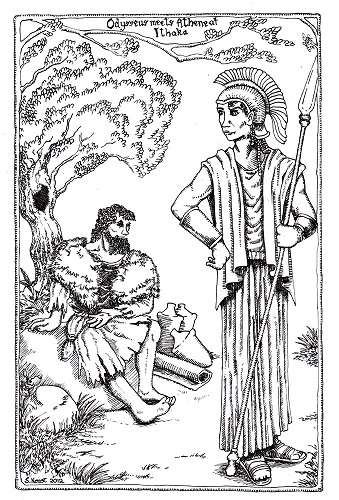

According to Tim Wright, Telemachus learns of two key pieces of information on his journey that aid in a successful recognition scene, when Odysseus finally reveals himself to his son in Rhapsody 16.

Wright explains: “From Nestor, Telemachus learns that Athena has in the past been Odysseus’ special protector (Od. 3.218–224), a fact that adds new significance to Athena’s current attendance on Telemachus himself. From Helen, he hears that Odysseus once disguised himself as a beggar and infiltrated Troy” (4.244– 258).

Athena’s guidance and Odysseus’ beggar disguise are most significant to his revenge plan on the suitors (Wright 2), both of which Telemachus has become privy to. This knowledge helps Telemachus accept Odysseus’ identity, acknowledging the beggar as his father in that key moment of recognition and demonstrating his trust. Dr. Emily Wilson, professor at the University of Pennsylvania, suggests that every character in the poem recognizes a different Odysseus, including his son: “Telemachus knows Odysseus as his role-model father, the man on whom his own honor and status in the world of adult men depends.”

“Telemachus knows Odysseus as his role-model father, the man on whom his own honor and status in the world of adult men depends.”

Wilson, Emily. The Odyssey. W.W. Norton & Company, 2018.

Without Athena’s advice and her divine hand guiding both men along their journeys, this recognition moment would never have succeeded. Telemachus needed to change and grow to fulfill his own destiny as the son of an Ithican king. He needed to hear stories of his father’s [polytropic] complex and clever ways to then practice those same traits on the suitors.

Like Father, Like Son

Many scholars have suggested that Telemachus’ journey represents a “coming of age story” or his “transition into manhood.” While this interpretation holds validity, Telemachus’ experiences transcend his transitional story. He does not just become more of a man, he becomes more like one man, in particular, his father; Telemachus becomes more Odyssean, as he is his father’s son. In “The Kleos of Telemachus,” Peter V. Jones explains that “…Telemachus’ consistently Odyssean behaviour in the last books seems to be critically connected with Athena’s promise of [kleos], true identity, at Book 1.95” (505).

Throughout the Odyssey, the relationship between father and son remains constantly entangled in their shared kleos—their shared social identity, as well as their final true identities: the self-assured Telemachus with the ability to become a rightful heir to the Ithican thrown and the returning Odysseus who reinstates himself as a father and epic hero. Furthermore, their relationship will exist in physical form upon their shared nostos (homecoming), the moment when father and son return to Ithaca simultaneously.

Telemachus’ recognition of his father in Rhapsody 16 is inextricably linked to Telemachus’ true identity as an Ithican prince. Dr. Sheila Murnaghan, professor at the University of Pennsylvania, describes this connection: “In the world of the Homeric epics, the recognition of identity also involves recognition in this broader sense [of achievement and status] because…identity is bound up with honor and prestige” (3). While Murnaghan’s comments focus on more of Odysseus’ character, the same premise can be applied to Telemachus and his succession, as he now believes in his ability to rule Ithaca (A. Gottesman 37). In one sense, the recognition scene establishes Telemachus’ glory for himself; he recognizes his father in disguise only because he has manifested the menos—or the power—of a prince.

Fit for a King

The message of Telemachus’ status actually reaches Odysseus well before “the big reveal.” In Homeric tradition, much of “achievement and status” and “honor and prestige” can be found in material goods, as both Murnaghan and Jones explain.

Athena relays Telemachus’ glory to Odysseus in Rhapsody 13: “…I sent him that he might be well spoken [kleos] of for having gone. He is in no sort of difficulty [ponos], but is staying quite comfortably with Menelaos, and is surrounded with abundance of every kind” (Butler, Od. 13.420-425).

In speaking of Telemachus’ surroundings, the Odyssey’s audience is reminded of the description of Menelaos’ “heavenly” palace (Butler, Od. 4. 43) and the royal treatment Telemachus (and Nestor’s son, Peisistratos) received upon their arrival:

“A maidservant brought them water in a beautiful golden ewer, and poured it into a silver basin for them to wash their hands; and she drew a clean table beside them. [55] An upper servant brought them bread, and offered them many good things of what there was in the house, while the carver fetched them plates of all manner of meats and set cups of gold by their side” (Butler, Od. 4 52-59).

The references to gold, silver, and plentiful food speak to the “abundance” that Odysseus would have known well and expected his successor to receive. Athena’s simple message thus confirms Telemachus’ status and offers Odysseus answers regarding his son’s kleos. Jones expresses that “…these words assure Odysseus that his son is worthy of him” (502). Her words also serve as another reminder that Athena, the goddess of war and wisdom, guides the narrative of the Odyssey, leading the two men to ultimately triumph together. Telemachus, armed with the knowledge of his father’s journey, and Odysseus, armed with the knowledge of his son’s journey, prepare for battle against the suitors. They return to their homeland of Ithaca well-equipped mentally and physically for revenge and restoration.

Works Cited

Cover image by KavallierNC.

A. Gottesman. “The Authority of Telemachus.” Classical Antiquity, vol. 33, no. 1, 2014, pp. 31–60. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/ca.2014.33.1.31. Accessed 20 Apr. 2020.

Butler, Samuel. Homer’s Odyssey. Revised by Timothy Power, Gregory Nagy, Soo-Young Kim, and Kelly McCray. Retrieved from: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/.

Jones, Peter V. “The Kleos of Telemachus: Odyssey 1.95.” The American Journal of Philology, vol. 109, no. 4, 1988, pp. 496–506. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/295075. Accessed 27 Apr. 2020.

Lattimore, Richard. The Odyssey of Homer. Harper Perennial, 1999.

Murnaghan, Sheila. Disguise and Recognition in the Odyssey. Lexington Books, 2011.

Nagy, Gregory. “A Sampling of Comments on Odyssey Rhapsody 2.” Classical Inquiries, 21 Feb. 2019, www. classical-inquiries.chs.harvard.edu/a-sampling-of-comments-on-odssey-rhapsody-2/.

O’Donnell, B.R.J. “The Odyssey’s Millennia-Old Model of Mentorship.” The Atlantic, Atlantic Media Company, 13 Oct. 2017, www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2017/10/the-odyssey-mentorship/542676/.

Redfield, James M. Nature and Culture in the Iliad: the Tragedy of Hector. Duke University Press, 2006.

Wilson, Emily. The Odyssey. W.W. Norton & Company, 2018.

Wright, Tim. “Telemachus’ Recognition of Odysseus.” Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Studies, vol. 58, 2018, pp. 1-18. Retrieved from: https://grbs.library.duke.edu/ Accessed 24 Apr. 2020.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Thank you so much for this article. As I read it, I listened to the Close Reads Podcast (Circe Institute) and felt like I was taking an Odyssey class. A poignant thing I learned was that Homer is not to be read once, but over and over again in a lifetime. These classics are not meant to be checked off a list, but savored and enjoyed.

Now, that is interesting. I never had the opportunity to read The Odyssey in school; I was in advanced classes, and expected to be “beyond” it (although I don’t know why, because The Odyssey, from the title on, is pretty complex). I love the idea of a whole class on it. You could even pair it with some adaptations like James Joyce’s Ulysses, or O Brother Where Art Thou.

This story brings new meaning to the expression about fish and house guests!

I’m a firm believer that everyone should read this poem every 10 years at least.

If there’s one thing I learned from this, it’s that the gods are fickle dicks and if you meet one, there’s a 99% chance you’ll die.

Greek mythology is something that I’ve been interested in since a very young age so naturally I love the story of Odysseus and his men encountering different mythical creatures and gods. Thank you for covering it.

Jealous! My school system did a little bit of Greek mythology, but it wasn’t a major part of the curriculum until after I graduated. I read so much, and have so many books on my TBR pile, it’s tough to get around to any specific genre.

It makes you question what it means to be a leader, and how pride can cause you a heap of trouble.

It kind of seems like Odysseus deserved to wander for 20 years, given all his bullshit? 🙂

Am in french speaking country and am doing my master in African-anglo american studies. I find your Odyssey explaining clear and helpful.

What?

Very interesting article! The experience of Telemachus is something that often gets overlooked. I always forgot how long the timeline/time span of The Odyssey is.

A timeless classic, astute observations and a very good analysis. A pleasure to read. Thank you.

I found the last few books describing Odysseus’s comeback and slaughter of the suitors exciting and gripping. I was intrigued by the fate of the collaborators such as the goatherd trussed up in the rafters and the maids strung up by the neck.

It has been many years since I read The Odyssey, and, while I appreciated it, I don’t remember actually enjoying it.

Good analysis, and I admire its epicness and marvel at the age of it, but not much else.

I mentioned to my mom I was reading this book and she immediately went to the attic of her house.

She came back down with a video tape, said it was one of her favorites, and popped it into the VCR.

What appeared on screen was a recording of a local newscast from when I was in the third grade around 1999. The piece was about how my class had read a children’s version of the Odyssey and then watched the 1997 miniseries. Two classmates get interviewed, one saying he liked the scary monsters and the other saying the underworld was cool. I am the last kid interviewed and spend the 25 seconds blubbering about how cute the actress who played Circe was while my dad who was a teacher there stood in the background making the ’30 year-old Boomer’ face.

Everyone who reads the thing seems to have an idea about the *one thing* the book is about, which is ridiculous, since even in translation you can see that it’s a bunch of different stories stitched together with some cosmetic cover-up.

Nonetheless, I have a theory for what one thing the book is about: the tragedy of hospitality. The moral code* is stressed throughout the book–be good to travelers and guests. Sometimes it’s rationalized (“the guest might be a god!” or “Zeus orders it!”), and sometime not. But the big actions of the poem are all tied to being good to guests, and how it’s just not actually possible. The two conclusions are Odysseus and crew slaughtering the suitors who, I will somewhat tendentiously argue, are guests; and the Phaeacians deciding that they have to place limits to their own kindness to guests. In other words, just as the Oresteia ends by ‘resolving’ the problem of mob-justice and revenge by setting up a formal judicial system, the Odyssey ends by resolving the problem of ‘unwritten’ laws of hospitality, by authorizing a weakening of them. I could really go out on a limb and say this is the ultimate end of the Trojan war: everyone is much more suspicious of everyone else, because too many people have abused social norms of kindness.

I don’t expect anyone to actually buy that, but I had fun coming up with the theory.

Lovely read. Despite being over 2000 years old, people are still hard-pressed to write a better adventure story than The Odyssey.

Homer sings for our time too!

Yes, as do all the best authors of the past.

Read the book after reading your article. Generally, I drag my feet on reading the classics because I think I’m going to be bored, but to my surprise I found I enjoyed The Odyssey tremendously.

A wonderful and enchanting masterpiece – I love this book.

Very insightful analysis; thank you very much! I am currently on Book V of the Odyssey.

This is the story that inspired nearly all of the stories that matter.

This is one story that really stuck with me all these years. I read this in Jr. High, and I loved it so much.

It seems like the overarching point here is that Telemachus needs to be explicitly taught to be a “real man” by following the explicit example of his father and male ancestors. I feel like there’s a real truth here: people’s conceptions of what it means to be a “real man” (or a “real woman” for that matter) aren’t automatic–they’re learned in the context of their families.

And to piggyback off that, what you learn depends on what kind of family you grow up in. No wonder so many people’s concepts of femininity and masculinity are completely messed up.

I gained new knowledge of Greek myths from this article.

Love the use of Greek terms to support your thesis. (I kind of geek out over Greek, Latin, and Hebrew stems–comes from being a Christian and having a couple of teachers who were really into vocabulary).

A good essay. I probably could have used this essay like we used Cliff Notes in high school when I had to read The Odyssey and write about it.

My favorite Telemachus moment is when his dad tells him to make sure he locks all the suitors’ weapons up in the closet, and he forgets and has to say, “sorry, my bad,” when all the suitors show up with swords, spears, armor, etc.

You’ve composed an article with striking breadth despite its brevity. I’m especially pleased with your inclusion of the theme regarding “The Disconnected Young Man.” That the “Odyssey” contains many of the most foundational and particularly western themes in literature is quite obvious and not disputed, but I would contend that it is this topic of the disconnected young man (or woman) that has been most influential in the ensuant western canon. Shakespeare’s “Hamlet,” Joyce’s “Ulysses,” David Foster Wallace’s “Infinite Jest,” and Dostoevsky’s “Crime and Punishment” (not necessarily western but the protagonist had been ‘contaminated’ by western intellectuality), but a few of the more studied and read works in the canon, all contain protagonists—dispossessed, forlorn—modeled rather explicitly after this theme found originally(?) in Homer.