Poe’s Horror: Reading “The Fall of The House of Usher”

“What was it – I paused to think – what was it that so unnerved me in the contemplation of the House of Usher?” exclaims Poe’s narrator when he first encounters the House of Usher (Poe, 231). If you have ever read anything by Edgar Allan Poe, you, too, have probably wondered what precisely it is about his horror stories that allow us, the readers, to sense a specific kind of horror. One way Poe achieves his effects is by foreshadowing the horror of the story’s ending in the story’s beginning, thus creating the sense that the horrible conclusion is inexorable. Another way that Poe creates an unnerving sense is by making his narrator act as a reader, thereby providing an example for the reader’s experience. At the story’s opening, Poe’s narrator shows ambivalence: he proclaims that a mix of aesthetic pleasure and terrifying atmosphere makes him shudder thrillingly. “[He] shuddered the more thrillingly because [he] shuddered knowing not why” (Poe, 236). Let us explore what exactly this horror is and how it works. While the topic of thrilling horror may seem overdone, Halloween season still sells big-time based on some version of this recipe, and a new production of “The House of Usher” has launching on Netflix. The claim in this article, though, is that reading can be an act of horror and that Poe’s text explores how this works.

Generally, it seems to spoil Gothic fun to delve too deeply into how its horror effects are achieved, not to mention that we tend to view literary effects as secondary to the priority of the meaning of the text. The latter notion, i.e., that meaning is the most important “thing” about a text or an action, has been seriously challenged in many literary/artistic settings. Indeed, Poe’s texts have often been used to illustrate such blurring of meanings and effects by various literary positions, ranging from, e.g., psycho-analytic to academic post-modern interpretations. These interpretative positions have diverse premises and widely divergent conclusions, suggesting that each approach’s agenda pre-determines its “findings.” Consequently, they are bracketed here. Instead, the focus is on reading as an act of horror, precisely as Poe’s text suggests in its first line when the narrator gets unnerved by reading the House of Usher. Let us read.

Encountering Usher

Our narrator is a reader: he reads the house called Usher, he reads the landscape, he reads his hosts, the Ushers, and he reads his own moods. Yet despite all this reading, he keeps insisting that he does not understand how and why his readings and the people and objects they relate to affect him the way they do. Is he simply a “bad” reader? Not according to himself; in fact, he considers himself a scrutinizing observer. In describing the decaying house, the narrator observes: “Perhaps the eye of a scrutinizing observer might have discovered a barely perceptible fissure [in the house], which . . . made its way down the wall in a zigzag fashion . . . “(Poe, 233). Of course, the reader of Poe, who also notices this, can pat herself on the back for being almost equally scrutinizing. The Poe reader is already beginning to identify with the narrator and his reading, and by implication his confusion. The narrator’s persistent scrutiny and desire to understand inevitably lure in most readers despite their apparent disbelief in the world Poe erects. The premise of any enjoyable reading is, after all, some amount of identification with the narrator. We are hooked – although we may claim to know not why.

We join the narrator when at twilight, he first sees the melancholy house of Usher.

“I know not how it was – but, with the first glimpse of the building, a sense of insufferable gloom pervaded my spirit. I say insufferable; for the feeling was unrelieved by any of the half-pleasurable, because poetic sentiment, with which the mind usually receives even the sternest natural images of the desolate or terrible.”

(Poe, 213)

The building impresses itself on the narrator and thus produces an “iciness, a sinking, a sickening of the heart” (Poe, 231). The almost sentient nature of the house, its eye-like windows, results in a depression that can only be likened to the “after-dream of the reveler upon opium – the bitter lapse into everyday life – the hideous dropping off of the veil” (Poe, 231). The narrator is bewildered by these impressions but claims that he is forced to “fall back” on the conclusion that:

“[T]here are combinations of very simple natural objects which have the power of thus affecting us, still the analysis of this power lies among considerations beyond our depth.”

(Poe, 231)

This claim appears a bit disingenuous. How can a reader know that she is capable of an analysis which is “beyond our depth”? Moreover, precisely how can an analysis of a combination of natural objects be attained, given that the analysis is of a higher order than the objects it deals with? It is almost like the Poe reader is being teased by being told she can never tease out how reading horror works.

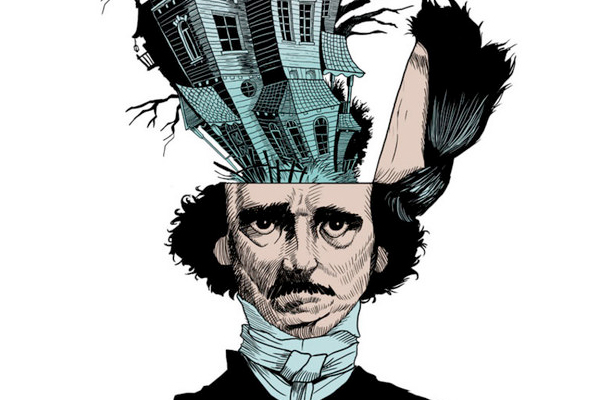

After the first view of the Usher house, the horror intensifies as we encounter the house host, Roderick Usher, who has sent for the narrator, his childhood friend to alleviate Usher’s extreme nervousness caused by his sister’s, Madeline’s, prolonged illness and death. However, Roderick’s condition is worsened by his morbid theory that the Usher house itself is sentient, and that this sentience has molded the destiny of the Usher family to the point of near obliteration: the family totally identifies with the physical, sentient house. As readers, we have returned to the weirdness of how natural objects have a power to affect us, a horrific power.

Roderick is on the point of total collapse, and he describes his struggle not with actual events but with anticipated effects of events, specifically the “struggle with the grim phantasm, FEAR” (Poe, 235). Indeed, Roderick is frightened to death, metaphorically and literally: he is metaphorically frightened to death throughout the story, and this frightens the narrator, which again may frighten the reader. Poe’s major twist is that Usher is also literally frightened to death. Towards the story’s end, the presumably dead sister, Madeline, returns alive from the burial vault, and she falls on her twin brother, who falls down dead, “a victim to the terrors he had anticipated” (Poe, 245). We should note, that Roderick is also a victim to being fallen on. In falling, Madeline finally dies.

That is some fall but it gets worse. Given the identification of the living-dead Usher family and the physical/sentient house of Usher, it is logical that at this point in the story, the physical house collapses, starting with the widening of what we were previously told was just an imperceptible fissure. As the narrator escapes (in the story’s last lines):

“[T]here was a long, tumultuous shouting sound like the voice of a thousand waters – and the deep and dank tarn at my feet closed sullenly and silently over the fragments of the ‘House of Usher.'”

(Poe, p. 245)

That sounds like utter destruction if it wasn’t for that “small” writerly gesture of italicizing the “House of Usher.” The italizing makes the name into a title, and titles relate to acts of reading: what survives is reading.

Reading as a Double or Reading as Embedded in the Text?

Let us take the exploration of reading a step further. If the narrator is a reader, then the house is her text, and since the house is doubled in the Usher twins, the narrator also reads the Ushers. Poe plays with this doubling effect almost ad nauseam: the house is mirrored in the water, the landscape mirrors the house, the house is mirrored in the twins who mirror each other, the story is mirrored in a poem, and the burial vault is mirrored in a painting of it. Finally, the shuddering narrator is mirrored by the “real” reader of Poe, the reader who shares the narrator’s feelings, who thrillingly shudders with him, scrutinizes with him, and struggles to put into words the presentiment of the inexorable horror, which culminates with the appearance of enshrouded lady Madeline.

The indefinite mirroring could lead to the observation that the text might be nothing but the play of reflections; as such, we could conclude that there is no original text, no text that mirrors any origin, any secure meaning. The mirroring is the meaning. Similarly, the effect, the horror, is the meaning, and there is no meaning hiding behind it. The text is its performance. This interpretation’s strength is that it accounts for the textual feature of reflection and its effects, but its weakness is that it places the readerly act outside the text. Reading the text is something someone is doing to the text. We get a binary between text and reader, and the assumption is then that the interpretative analysis is something the literary theorist does to and for the text. What is the problem with that approach? This approach is an ideology about reading, and it does not do justice to what happens in reading “The House of Usher,” where we have clearly seen that acts of reading are already embedded. What happens if we then consider reading as an act already embedded in the text? Since the text has already “read” reading, the Poe reader’s reading is haunted by text’s reading. No one can read Poe without Poe’s reading first falling on it. Granted, his (any?) text does more than read reading: it entertains, enlightens, spreads joy, horror, etc. But (some) texts also read reading. Therefore, descriptions of Usher (the house and the twins) are readings about reading.

Reading Reading: The Fall

Granting this approach, we discover some kind of insufferable horror, a horror that escapes aesthetic play. Rather than being a play of mirrors and reversals, which all turn out to shuffle either binaries or identical twins, we find ourselves faced with a horror that follows a downward movement without ever going in depth: it moves from the high to the low to a lapse to a dropping. It keeps falling.

The text falls, from the title to the opening lines, to the fall of Madeline upon her brother to the sinking of the physical house of Usher. What do these falls have in common? They all mix the metaphorical and the literal, and they mix them in such a way that the metaphorical is taken literally. This turn exposes that a metaphor cannot ever erase the literal, even if metaphors seem to only work if they do so. Moreover, the whole idea that we can exchange one “thing” for another with no remainder – which is the underlying logic of metaphor – falls apart.

Falling is so ordinary, though, ironically, this ordinariness seems over-the-top in the context of the unbelievable appearance of Madeline. Her literal fall is quickly re-inscribed into the text’s horror as we see the house sinking into the deep and dank tarn and the narrator fleeing the premises, only leaving his story and its reading behind. Considering that Madeline’s fall is passed over quickly, is it all that horrible?

Madeleine’s literal fall is perhaps easily glossed over, buried by the text, and it can become imperceptible like the fault line of the house of Usher, yet it is precisely this literalness that is a stumbling block for a narrator and a reader who constantly try to make sense of things through a metaphoric logic of substitution according to which one thing – a house, a person, something alive, something dead – can stand in for another. As noted, the narrator admits that horror is created from a power combining “very simple natural objects” (Poe, 231), but he will not further investigate how that works. Indeed, for him, the recognition of something as literal is something he is forced to “fall back upon.” His phrase here is intended as a figure of speech because the literal always escapes him, or maybe we should say, he escapes from literal reading.

Another argument in favor of Poe’s destruction of metaphor is his creation of situations where it becomes impossible to decide if we know whether or not something truly significant is the case: are people dead or alive? Live people are buried; half-dead people are alive; dead things (houses) live deadened sentient lives. The metaphorical, figurative exchange between death and life has become meaningless if we cannot distinguish between life and death, if we cannot decide if we know or do not know. Why does Poe create these scenarios, apart from the thrill of horror? It could be argued that Poe is after something sophisticated, from a literary perspective. He wants to show that metaphoric logic (exhanging this for that, by trying to erase the literal) is not necessarily identical to meaning. The implication is that when a text knows its own meaning-creation, it knows itself. It has read itself. Of course, no text resists metaphor and the logic of exchange to build meaning forever, nor does it need to. One imperceptible crack in how we create meaning in reading is enough to get us to question. It is inevitable – and this inexorability is the true horror: questioning meaning.

Yet we can fall even further. Returning to Madeline’s fall, it is precisely the literalness that deflates the heightened atmosphere of the inexorable horror. Whatever we expect from the prematurely buried, we do not expect them to fall on anyone. It deflates the fear. Such deflating also happens as the alive Madeline frightens herself to death. It seems overly absurd. A revenant might be expected to frighten others to death, but we do not expect them to frighten themselves to death. Actually, we expect phrases such as “frightened to death” to be taken in their metaphorical sense, and not be taken literally, not to be taken on their words. Taking words on their word can lead to all sorts of horrors, such as the horror of someone losing his breath, as Poe shows us in the story “Loss of Breath” (Poe, 395), or the horror of waking up as a literal monstrous vermin as Kafka shows us when he takes literally the cliché: “salespeople are a pest”. Perhaps it is Poe’s ultimate meaning-defying gesture that he takes words on their word, whether it is “frightened to death” or the challenge of the title, where the meaningful combination of letters “house of Usher” after all could fall apart into the simple repetition of the non-meaning letters e/s/h/o/u (and adding a single f and r). Letters or meaning? Both and neither.

Choosing to read a la Poe

Perhaps we feel like abandoning reading reading just like Poe’s narrator, who cannot withstand the collapse of his house of metaphors because it is too scary. If non-meaning is at the heart of meaning, how can we mean something, anything, in a safe, secure manner? Perhaps this is the wrong way to look at the matter, asking the question as if one can avoid Poe’s horror of glimpsing of non-meaning. A more productive way to use our analysis would be to keep reading humble. We could add the above acts of reading to everything we already do when we read. Of course, there will also be the enjoyment of reading, the mix of shudder and delight; we will no doubt still insist on “finding” many meanings in texts because that is what we do, “knowing not why,” to echo our narrator. However, reading reading a la Poe keeps us a bit more honest as readers, admitting that we sometimes do not “find” but rather “create” meanings in our readings and that if we were to read those acts of readings they would – fall. There would be no sublime shuddering, just an ordinary fall. And if we repress this insight, we might find ourselves in another Poe story where our denials end up sitting on top of what we try to bury, purring like a certain black cat. That, though, is another story.

Works Cited

Poe, Edgar Allan. The Collected Tales and Poems of Edgar Allan Poe. Modern Library ed. New York: Modern Library, 1992.

Select Bibliography

Auerbach, Erich. Mimesis: The Representation of Reality in Western Literature. Princeton: Princeton UP, 1953.

Derrida, Jacques. Of Grammatology. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins UP, 1976.

Gadamer, Hans. Truth and Method. New York: Seabury, 1975.

Johnson, Barbara. “The Frame of Reference: Poe, Lacan, Derrida.” Yale French Studies: 457.

Koelb, Clayton. Inventions of Reading: Rhetoric and the Literary Imagination. Ithaca: Cornell UP, 1988. Print.

Man, Paul. Allegories of Reading: Figural Language in Rousseau, Nietzsche, Rilke, and Proust. New Haven: Yale UP, 1979.Newmark, Kevin. “Irony on Occasion.” (2012).

Ricoeur, Paul. Interpretation Theory: Discourse and the Surplus of Meaning. Fort Worth: Texas Christian UP, 1976.

Ricoeur, Paul. The Rule of Metaphor Multi-disciplinary Studies of the Creation of Meaning in Language. Toronto: U of Toronto, 1993.

Waters, Lindsay. Reading De Man Reading. Minneapolis: U of Minnesota, 1989.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Loved this article when I edited it, and am so happy to see it on the site! Congratulations, and thank you for making me want to take the perspectives you bring to light in this piece into my own readings of Poe in the future!

Hi Siothrun, Thank you for being a supportive editor. Gitte

As a big Poe fan, this was a great read.

Hi Sunni Ago, Thank you for being a supportive editor. Gitte

I stormed into Poe’s writings as a teen- and when I finally fought my way through to the other side, I was a shadow of my former self.

For my money, there’s no scarier story than “The Fall of the House of Usher.” Maybe there are better ones. But none scarier.

Though, I’m willing to be proven wrong.

Scarier story? The Confession of Charles Linkworth by E.F. (Fred) Benson of Mapp and Lucia fame

Yeah. Frightens the bejesus out of me every time I read it.

I think it’s a little the opposite, it’s one of the best stories ever written (although how would I know since I have not read 99.999999% of all stories). It is not so much scary to me as poetically intensified psychology of dread, anguish, mental disintegration, drug use, languishing illness, neurasthenia, terror, in a poetically intensified ambiance of oppresive moldering, stultifying, decay. Of course in our own time the telly, the news, fiction, and movies have made all of the foregoing rather common. Those words “poetically intensified” are important to understanding Poe. He was a highly wrought author baroque perhaps to the point of the churrigueresque, but he did it wih such absolute mastery, and beauty as to make it awesome.

See below DVGriffen’s discussion of Usher. You can of course just pick it up and read it as historical Gothic. But, with no disprect, it is not like Lovecraft or Stephen King or other masters of the macabre, and I mean masters, Poe is in a unique and often demanding, literary class of his own.

BTW I believe his true immortality is in his prose fiction, but his poetry is powerful however sparse. Personally I don’t think it is one bit overwrought, however highly wrought, although maybe somewhat tortured. I have no problem with tortured. It would be very overwrought if weren’t so good. But it is so good and therefore is not overwrought

I think Poe is one of those writers (like many writers beloved by cinema) whose ideas are greater than his prose. And each one of his stories has a cracking, if rather morbid, idea.

Love Poe. Vivid. Contorted. Quiver.

The gothic vibes did not disappoint in this creepy tale.

I really do love this story. It’s so atmospheric and gloomy, the tension is stifling and it’s so strange and unusual.

Great creepy short story from one of literature’s finest masters.

I found Usher to be an intriguing character. Utterly creepy but really interesting. His condition of hypochondria and axiety made him even more intriguing, and also, it was crucial to the plot.

The ending… damn. I loved it, but damn. Poe sure knew how to write horror, and I love that.

I’ve recently read a meta-linguistic narrative in which the author said “No useless words, all of them, the absolute totality, loaded with signification. Novel readers have time to lose; short-stories readers, don’t.” While reading this Poe’s story, I couldn’t agree more.

I adored the gothic style, just as the guilt, disgrace and fear carried by Roderick Usher. His hyperesthesia and hypochondria really potentialized the horror in the story.

I recommend listening to this book instead of reading. With proper sound effects, this book is purely terrifying!

It’s not a book. It’s a short story.

To be honest, I didn’t like this story. It doesn’t make any sense until the end. There is really nothing to learn from it except: Don’t bury your sibling alive when you’re mentally ill.

NOBODY writes insanity as well as this man.

The theme is really dark and mysterious, which made the book kind of scary, but the way it was written made me travel two centuries back so easily.

I really hope that my English will get better so I could read more ancient books and actually understand them.

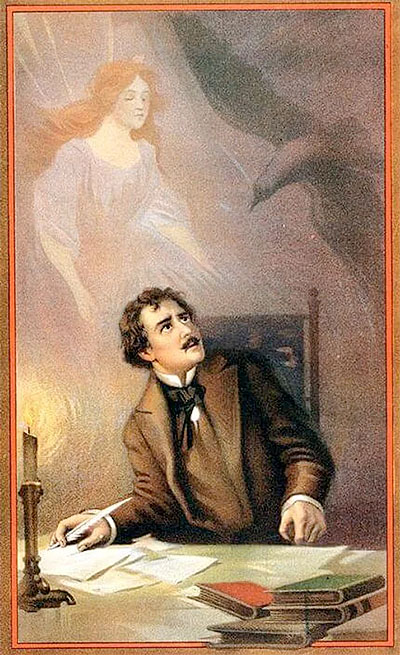

Great post for this time of year. I especially love the images. Also, I am as always honored to have helped with the revisions.

Hi Stephanie, Thank you for being a supportive editor. Gitte

This is the first of Poe’s stories I’ve read.

This is my first Edgar Allan Poe read and wow I really enjoyed it. Thanks for writing about it.

This one is a great example of how an author such as Poe gets straight to the point.

I agree. He doesn’t bore the reader with lots of filler, but rather only describes every detail that is important to the story.

When he was describing Usher’s maladies I felt a twinge of hypochondria and later as night fell in the story my heart raced with the unknown suspense of what terrors would be in store for me.

The audiobook I listened to was narrated by Tony Addison. Highly recommend that one!

Are you normal or do you feel like you simply HAVE to read the book any new film or show is based on before watching the new film or show.

Possibly the darkest and most literary haunted house story ever written. I feel as if Poe wrote it as a means of describing the depression that I believe plagued him during his too brief life.

Great article. And just in time for Halloween!

Poe really knows how to set a mood and a cold, depressing, scary one at that.

This story is what made me like Poe more than The Raven, The Telltale Heart, The Pit and the Pendulum, or any of his other works did.

I still try to read this tale every year around Halloween. I can’t explain what the appeal to me is of a house that drove all it’s residence insane and then kills them but it never fails to bring me back.

Lovecraft called Poe his “God of Fiction” and considered “Usher” Poe’s masterpiece. There’s very good reason for this!

One of my favorite Poe stories. I remember reading this in High School and was impressed with it then.

Edgar Allen Poe is such an incredible writer. My favorite by him is Annabel Lee and The Raven. This one is just as great! 🙂

Such an eerie, psychedelic and surreal read. Poe is a master.

If he isn’t the king of spooky, I don’t know who is.

To me it seems like an extension of the theme developed in The Premature Burial…. gothic horror at its best!

I actually read this quite a number of years ago when I was reading a lot of Poe. I think around 1997 or so. At some point I saw the movie version with Vincent Price and it was creepy good fun.

I came across a dramatized version of this yesterday from audible and listened while out for a walk. It is FANTASTIC ! I highly recommend all three versions. I have had a long time love of Poe. He is genius. This gave me such a thrill yesterday. I really want to just play it again. It is raining today. In the dramatization we get to hear the sounds of the coming tempest. The sound of rain is perfect, with the wind blowing in the audio I listened to.

Poe never fails at creating an immense feeling of disturbing dread.

One of the best short-stories I have read so far.

Deliciously dark and devilishly comic.

This is a complex subtle tale open to a lot of interpretations.

I love the unnerving feelings that this story produces. The perfect amount of horror for me.

Not my fav by him but I love Poe!

My kind of happy ending.

I appreciate how you comment on the double-meaning of the word ‘reading.’ Especially through a first-person narration, themes of perception/reading are so much stronger and contribute not only to the sense of unreliability as we guess what’s being read ‘correctly’ but also that the tale itself becomes self-aware in a ‘one without the other’ relationship between narrator and reader.

After watching the Netflix series, I re-read the book. “Keeping reading humble” is something I need to reflect on. Thanks for this great piece.

I love the idea that part of what makes Poe’s writing so scary is the fact that he takes the literal meanings of expressions that are generally read as metaphors.