Pynchon, Vonnegut, and Art of the 1960s: Meaningless Post-modernism

The 1960s is generally known as a time of upheaval. Everything was changing—politics, higher education, society roles, culture, etc. So much was happening that some revolutionary aspects of history get overlooked in the general mayhem—one of which is the art scene. By the mid-1960s, there were at least three major art movements on the rise—Pop Art, Minimalism, and FLUXUS—all of which not only reflected the changing times, but also influenced other parts of society as well. Thomas Pynchon’s The Crying of Lot 49 and Kurt Vonnegut’s Cat’s Cradle are two novels that feature examples of how art at this time interacted with another part of society, namely literature. A closer look at this interaction can provide a further understanding of these two particular postmodern works and the general art scene of the 1960s.

If you were to imagine The Crying of Lot 49 and Cat’s Cradle each as a postcard, what do you think would be featured on the picture side of the card? In both of these novels, there are many examples of art, but one could argue that each novel features a painting that stands out from the rest. In The Crying of Lot 49, this painting would likely be Bordando el Manto Terrestre by Remedios Varo. According to the text, the painting is depicted as follows:

“In Mexico City they somehow wandered into an exhibition of paintings by the beautiful Spanish exile Remedios Varo: in the central painting of a triptych, titled ‘Bordando el Manto Terrestre,’ were a number of frail girls with heart-shaped faces, huge eyes, spun-gold hair, prisoners in the top room of a circular tower, embroidering a kind of tapestry which spilled out the slit windows and into a void, seeking hopelessly to fill the void: for all the other buildings and creature, all the waves, ships and forests of the earth were contained in this tapestry, and the tapestry was the world. Oedipa, perverse, had stood in front of the painting and cried.” (Pynchon, 11-12)

However, when examining the painting separate from the text, you might interpret it differently. In reality, nothing about the painting suggests the women are Rapunzel-like prisoners. Even though viewers can only see two of the “heart-shaped” faces, clearly both of the women are smiling. Furthermore, “slit windows” is misleading because they are actually too low for anyone in the tower to see out of. Strictly speaking, the only real window is the imaginary and/or metaphorical window opened up by the artist to view the scene. Additionally, the tapestry flowing out of the windows does not seem to fill any void. There are several places left uncovered and, notably, these places are all bodies of water. So the tapestry does not seek to fill the entire world, just the landmasses. Last but not least—and certainly most obvious—there are two figures completely ignored in Pynchon’s description. To any other viewers, these two figures would be hard to overlook, but Oedipa makes no reference to them. Overall, Pynchon renders the original painting meaningless with his inaccurate description. It is almost as if he is talking about an entirely different painting. (Brown)

In Cat’s Cradle, the postcard picture would probably be Newt Hoenikker’s painting of a cat’s cradle—a game of no meaning. It is a game of string that forms nonsense forms, a puzzle without all the pieces. Despite its name, the game has no cat and no cradle. Throughout the novel, the cat’s cradle comes to represent all the delusions that run rampant in the characters’ search for the final meaning, and so the story becomes a game with no end.

When one compares these two postcards side by side, one might find a post-modernist connection through the theme of meaninglessness. Post-modernism is based on the idea that the traditional Grand Narrative is rendered meaningless in favor of skeptic perspectives. Newt’s painting is about a meaningless game and the Bordando el Manto Terrestre is meaningless as an inaccurate description. The fact that post-modernism tends to be presented as meaninglessness compounds the connection between these two novels.

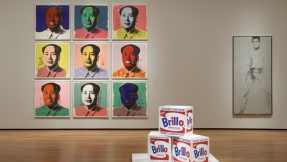

But how do these two pieces of literature tie into the overall art scene of the time period? First, let’s take a brief look at the three major movements. Pop Art was a movement mainly influenced by consumerism. After World War II ended, there was an explosion in consumerism that remained high all the way through the 1960s. Soldiers came home to find a country that had been fighting the 1930s Great Depression had been replaced with a country that now had money and jobs. It became the era of Tupperware, and Americans were eager to spend their money on houses, televisions, cars, and anything else they could afford. People believed that happiness could be bought with goods and services. (Rotillie)

With this consumerism fever, advertising skyrocketed. Businesses began churning out catchy commercial jingles and noticeable brand names one after another. Pop Art was born when artists began equating this mass consumerism with fine art. For example, Pop artist Andy Warhol took logos and products, such as Campbell soup cans, out of their commercial context and presented them as art. As a matter of fact, Warhol aptly describes Pop Art with this comparison: “When you think about it, department stores are kind of like museums” (Rotillie). In other words, mass advertisements and ordinary objects transformed into art. This art of appropriation became challenge against the traditional notion of fine art.

Another aspect of Pop Art is the idea of repetition. Pop artists took the idea of reproducing images from the mass media as a visual means for expressing emotional detachment. Warhol describes that when a viewer sees “a gruesome picture over and over again, it doesn’t really have an effect” (Rotillie). Like a droning news broadcast, repetition dissolves meaning and, with it, the ability of images to affect the viewer.

In contrast to Pop artists, Minimalists created art that featured pure, geometric properties meant to be “explored as ends in themselves rather than as metaphors for human experience” (Rotillie). In other words, Minimalists were interested in the viewers focusing on the physical essence of their art. For example, artist Donald Judd is known for creating a structure that looks like a stack of royal blue floating bookshelves. Minimalists like Donald Judd did not want to produce art that concentrated on the human narrative or the artist’s craft; they wanted to create simple, reductive forms. Essentially, objectivity becomes a priority over subjectivity for a Minimalist.

Furthermore, Minimalists created their art with common industrial materials such as aluminum, plywood, sheet metal, and Plexiglas. The use of ‘non-art’ materials was the Minimalist’s way of rejecting the traditional notion of fine art. This concept of non-materials is very similar to how Pop artists used mass goods and advertisements as fine art. In addition, Minimalists produced art that interacted with the viewer’s space. Gone was the art contained in a frame or cordoned off with a rope. The art was displayed with no barriers, forcing the viewer to reconsider his/her relationship with that particular piece of art. Overall, this spirit of innovation and pushing the boundaries is characteristic of the 1960s counterculture set of mind.

FLUXUS was an international movement that derived its name from the Latin word for “flow.” As a movement that “advocated purging the world of bourgeois, commercial, and professional art” (Rotillie), it was all about fun and games. For example, a well-known FLUXUS creation is the Flux Year Box 2, produced by a group of artists led by George Maciunas. Basically, this box held a variety of entertainment, including flip books, cards, small games, and films. The Flux Year Box 2 also highlights the notion that FLUXUS artists valued community over individuality. Most FLUXUS art was created by groups of artists, rather than one single artist.

FLUXUS art emphasized the idea that there are rules to playing games, just like there are understood rules to creating art, i.e. making, buying, selling, canonizing. All in all, FLUXUS art sought to reject traditional fine art, just like Minimalism and Pop art. FLUXUS artists wanted to create games that could be enjoyed by anyone, in contrast to the serious art that could only be enjoyed by astute art critics.

All three of these art movements had in common the rejection of traditional fine art. Pop Art focused on consumerism, Minimalism focused on objectivity, and FLUXUS focused on games—none of which were traditional fine art. One could go so far as to argue that these art movements rendered traditional fine art as meaningless. In light of this analysis, these art movements can be compared to Vonnegut and Pynchon’s artwork through the theme of meaninglessness. In some form or fashion, these different pieces and kinds of art can be interpreted from a postmodernist perspective of meaninglessness. The art movements represented traditional fine art as meaningless. The Bordando el Manto Terrestre is rendered meaningless through an inaccurate description. The painting of a cat’s cradle features a meaningless game.

From hippies to Hell’s Angels, many things were changing during the decade of sex, drugs, and rock ‘n roll. When one thinks of this time period, they generally do not think of the art scene, but nevertheless, art was changing as well during the 1960s. Understanding the various movements—Pop Art, Minimalism, and FLUXUS—helps one understand the postmodern theme in art of other areas in the 1960s, namely literature works such as Kurt Vonnegut’s Cat’s Cradle and Thomas Pynchon’s The Crying of Lot 49. With analysis, one can find that these different forms of art all share a postmodern connection to the theme of meaninglessness. Part of the pleasure in studying the 1960s is continually discovering little nuggets of insight like this analysis amidst all the various dimensions of upheaval.

Works Cited

Brown, Bill. “Playing the Post Card of Thomas Pynchon’s The Crying of Lot 49.” Not Bored. 27 February 2004. Web. 11 April 2013 < http://www.notbored.org/crying.html >

“Bordando El Manto Terrestre.” With Hidden Noise. 27 December 2008. Web. 11 April 2013 < http://withhiddennoise.net/2008/12/27/bordando-el-manto-terrestre/ >

Mattessich, Stefan. “Ekphrasis, Escape, and Thomas Pynchon’s The Crying of Lot 49” 1998. Web. 11 April 2013 < http://pmc.iath.virginia.edu/text-only/issue.598/8.3mattessich.txt >

Rotillie, Susan, “Art in the 1960s” Walker Art Center, artsconnected, n.d., Web. April 13, 2013 < http://artsconnected.org/collection/118487/art-in-the-1960s >

Plackova, Eliska. “Postmodernist features in Vonnegut’s Cat’s Cradle.” Marek Vit’s Kurt Vonnegut Corner. 2002. Web. April 12, 2013.< http://www.oocities.org/marek_vit/kv_cat_postmodernism.html >

Patterson, Kellee. Kissel, Adam ed. “Cat’s Cradle Themes”. GradeSaver, 14 April 2006 Web. 12 April 2013. < http://www.gradesaver.com/cats-cradle/study-guide/major-themes/ >

Pynchon, Thomas. The Crying Lot of 49. J. B. Lippincott & Co., 1966. Print.

“Cat’s Cradle Theme of Art & Culture” Schmoop. Schmoop University, n.d. Web. April 12, 2013. < http://www.shmoop.com/cats-cradle-vonnegut/art-culture-theme.html >

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Overall, very well written article. Good job. However, I feel like much of ‘The Crying of Lot 49′ is cleverness for cleverness’ sake (like the names Oedipa Maas and Pierce Inverarity, for example). In this way it reminds me of David Foster Wallace’s fiction – original, skillful, but ultimately unsatisfying.

The first chapter of the novel is pretty good — it brings out some interesting characters with some very funky names (Oedipa? Mucho? A shrink named Dr. Hilarius?) with neat senses of humour. It ends strongly, with the image of Oedipa imagining herself as Rapunzel and that image just running away and picking up steam, doing its own stuff, quite alive as the chapter closes out.

But unfortunately… the rest of the five chapters do not come near the intensity of the first chapter. And when Pynchon goes headlong into the Jacobean play (“The Courier’s Tragedy”), he comes out all alone, his readers left behind on the other side, dead cold and wondering just what the heck happened to this novel.

That’s how I feel about Catch-22 (which deserves Ice-Nine) while I love Cat’s Cradle.

Pynchon was able to synthesize obscurant historical references, pop culture, conspiratorial paranoia and drug use very well. And what Kurt Vonnegut can do with the written word just amazes me. Cat’s Cradle is both a rambling diatribe of apt social observations and a finely crafted novel at the same time.

The first time I read Cat’s Cradle was on a trip through Illinois heading for Chicago. I started laughing out loud almost immediately and the other people in the car had to hear the ‘funny parts’. Soon I was reading the whole book out loud and all of us were laughing our heads off constantly. This remains for me the best example of Vonnegut’s use of black humor to make a serious point. Thanks for the nostalgia.

I’ve been reading Pynchon for some time, and one of the things that still gives me a fit is when he is changing his voice. In the section closing the first chapter of Lot 49, for example, it is subtle. Is the narrator speaking for Pynchon the author? Or is the narrator speaking and describing Oedipa’s mental state. Or, is the narrator speaking for the weavers who are creating the tapestry, “which is the world?” The author seems to know. Could she(Perkalert) e-mail me her thoughts on this in a private communique?

Max Dudious

Strong piece. You know, I don’t know which is my favorite Vonnegut novel, because the one I’m reading always seems like the best one at that moment…

Thanks PerkAlert. Cat’s Cradle is a unique and creative look at the end of the world and I would personally recommend anyone to read it.

One of the things that I think gets overlooked in Pynchon is his scatological assault on the bourgeois through humor. It may seem dated now, but some scenes in Gravity’s Rainbow are so funny and sad (the dinner scene) and I hope that as time goes on Pynchon becomes less known as that impenetrable author who wrote really long books.

The postcard comparison is quite fitting considering the preoccupation with communication and the postal system in The Crying of Lot 49. I’d love to see this article informed by deconstructivist theorists (who came to their heyday in the 80s).

This is a really interesting connection, and not one that many people would easily make. Very well written piece! It makes it seem like postmodernism functions in part as a critique of the accepted notion of “fine art.”

I would argue that it’s not meaninglessness that they were concerned with, but rather the metaphysical possibility of meaninglessness as presented in a post war era. I don’t think these artist were necessarily reaching the conclusion of meaninglessness, but an overall challenge to previously established meanings to life, art, and culture.

The search for meaning is such an essential part of The Crying of Lot 49, and where Oedipa fails to find, or misinterprets meaning is an essential part of the narrative for me. I would like to know more about what you think the presentation of signs and symbols, or denial of in the case of minimalism, tell us about the times in which these works were made.

I think its an interesting connection worth continued exploration.

Great article! Your connection between postmodernism and Pop Art, Minimalism, and FLUXUS is intriguing, as I’ve never thought of postmodernism in relation to the art world.

Strong article. I’m wondering a lot about the meaningless and what that means though. The three movements you recount are meaningful for their own reasons: redefine fine art leaving fine art meaningless, industry, and games. These may be meaningless or provide meaning to a more general populous that was once left out of the loop.

The first part of your article is a welcome close-reading of Pynchon with a nice visual aid. Your comments, though, about the difference in the actual artwork and the book’s description is rather nit-picky. I think we can reasonably assume that the description of the picture is in part Oedipa’s memory and the sensory impression it had one her, which is bound to be less than meticulous (can we allow Pynchon a little poetry?) The second part of your article is a bold attempt at comparing two different mediums, however the abstract nature of all the works you discuss and the significant differences to begin with, leave one with an inescapably superficial connection between the works.

Thanks for your comment! You make an excellent point, as I did not intend for my analysis to be an exceptionally thorough examination. I think the amount of research that kind of analysis deserves would belong more in a thesis or research journal. I was merely trying to skim the surface of what might be a unique postmodern connection between these works. Yes, I was “nit-picky” in my analysis of the Bordando el Manto Terrestre, but it was to prove a point. It may not be perfect, but like you said, it’s “bold,” and how is anything accomplished without a little boldness? 🙂

You drew some excellent links between literature and fine art. I think the connection between literature and the artistic movements that dominated the creative environment in which they were written is an important part of understand the significance of that literature, yet it is often overlooked. I would be interested to hear your analysis of other artistic movements such as Dada and if they had a bearing on the literature of that period.