Strange Magic’s Original Sin

Perhaps Strange Magic was doomed from the outset. After the widespread disappointment of the Star Wars prequels, boasting its story came from the “mind of George Lucas” did this strange little film no favors, nor did its claim of offering a “new twist” on fairy tales distinguish it among similar films glutting the market. A quiet release in January of 2015 and a sound critical thrashing ensured it suffered the “all-time worst-opening ever for a film an animated film in 3000+ theaters” before fading again into quiet obscurity. Critics, then and now, have traced its failure to the curious decision to tell its story as a jukebox musical and then shoving fourteen songs into an hour and a half film. But none, or very few, have traced its failure to a more fundamental, and yet more damning flaw. By featuring fairies as its main characters, Strange Magic fails to delineate the limits, magical and ordinary, of its fantasy world, and thus fails to create a compelling magical world. Despite advertisements to the contrary, Strange Magic is not a fairy tale.

What is a ‘Fairy Story’?

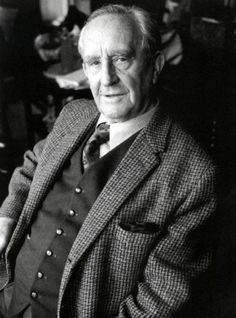

Now, such a sweeping claim requires some qualification, which requires some definition. In 1939, J.R.R. Tolkien, the Oxford professor of philology and world-renowned author of the Lord of the Rings trilogy, penned an essay which is still one of the most thorough and definitive analyses of the fairy tale (or “fairy story”) ever written. “On Fairy Stories” not only defines the fairy tale as its own genre but includes ample examples of what a fairy tale is and is not. According to Tolkien, a fairy story is not about magical creatures per se, but is “about…Faerie, the realm of state in which fairies have their being. Faerie contains many things besides elves and fays, and besides dwarfs, witches, trolls, giants, or dragons: it holds the seas, the sun, the moon, the sky; and the earth, and all things that are in it: tree and bird, water and stone, wine and bread, and ourselves, mortal men, when we are enchanted” (113). The mere presence of magical creatures does not a fairy tale make, and several of the most successful fairy tales hardly include the slightest whiff of them. It is the presence of magic, a certain kind of “enchantment,” as Tolkien puts it, that defines fairy tales and gives them their peculiar power.

While clarifying this definition, Tolkien makes an almost passing comment which proves foundational to understanding the failure of Strange Magic. In picking apart the existing definitions (“a story about fairies”), he argues that they are so inadequate in part because in truth “most good ‘fairy-stories’ are about the aventures of men in the Perilous Realm or upon its shadowy marches” (113). The few that do exist “are as a rule not very interesting” (113). Since elves and fairies, he argues, are “not primarily concerned with us, nor we with them. Our fates are sundered, and our paths seldom meet” (113). A fairy tale instead derives its primary interest from the “chance crossings” of the fairies and men, and the encounter of those unfamiliar with it with the indescribable realm of Faerie. A successful fairy tale may not feature fairies but will give a taste of that “realm of state in which fairies have their being,” and the enchantment it engenders.

The easiest and most often successful way of communicating this atmosphere or magic or enchantment is to have a character, preferably the protagonist, come to the world of Faerie from the “outside.” To impart a full sense of this awe and wonder, we need a character coming from the outside, for whom this strange realm is utterly new, beautiful, and frightening. While it’s not necessary for a modern kid to stumble into a magical world–though such a device is effective in the right hands, as with C.S. Lewis’s Chronicles of Narnia, or L. Frank Baum’s The Wonderful Wizard of Oz–the fairy story still requires a protagonist unfamiliar with the workings of this world. Hence, a typical Grimm’s fairy tale often features children or tailors or second sons drawn into a fantastic world, their prosaicness contrasting with the magical elements within, and their ordinariness allowing the original listeners or readers to identify with them and discover the magical world together.

Tolkien’s own Lord of the Rings provides a choice example in the hobbits. They are not men, but their manner of speaking, and their provincial, down-to-earth perspective grounds the reader and provides a familiar frame of reference to begin this epic fantasy saga. Seeing the world for the first time along with the protagonist allows us to discover the strange world simultaneously, giving us essential background information in an organic, even subtle, way.

What Makes an Elf an Elf?

Strange Magic conspicuously lacks any such character. Instead, the story throws us into a wholly unfamiliar world without any sort of background or context. We are expected to understand intuitively what it means that Marianne and Dawn are butterfly fairy princesses, what differentiates elves, fairies, and goblins (besides appearance), and the culture, taboos, and general attitude of this world towards magic. The characters all “look” the part, with their diminutive size, ungainly proportions, butterfly wings, and pointed ears, but they think, act, and react as we expect normal human characters would. Marianne might have butterfly wings and pointed ears, but she handles her betrayal with the same anger and bitterness we might expect of any ordinary young woman. Likewise, Dawn acts no different from a typical flirty teenager, Sunny the elf is as desperate as any a self-professed “nice guy,” and Roland’s cartoonish caddishness has little to distinguish him among other chauvinistic animated villains.

On the flip side, however, since they all belong to this magical world, and so see magical primroses and the power of flight the way we do aspirin and the wheel, we are given no entryway into their world. Since the Perilous Realm is home for fairies and elves, they cannot communicate the sense of thrill, wonder, and even fear that Faerie inspires for an outsider. Our fairyland is their workaday world. If fairies, elves, goblins, and magical primroses are all par for the course, we have no sense of what distinguishes their world from our everyday one, losing any sense of magic or Faerie. If we can’t see how this world is different from ours, or understand what’s supposed to make it magical or wonderful–well, why should we care?

Contrast the fairy characters here with the characters like Legolas, Elrond, or Galadriel in Lord of the Rings, or the inhabitants of the spirit world in a more modern work like Hayao Miyazaki’s Spirited Away. Legolas, by no means the most rarified elf in Middle Earth, often reacts in such a way as to remind us just how much elves differ from mortal creatures. When entering Fangorn in The Two Towers, he tells his companions, the 88-year-old Aragorn and 140-year-old Gimli, “[The forest] is very, very old…So old that I almost feel young again, as I have not felt since I journeyed with you children” (480). When Aragorn and his companions come to the entrance of the Paths of the Dead in The Return of the King, the narrator mentions “there was not a heart among them that did not quail, unless it were Legolas of the Elves, for whom the ghosts of Men have no terror” (769).

Hayao Miyazaki’s Spirited Away achieves something similar with the spirit world Chihiro and her parents stumble into; from the first glance the spirit world is wholly different from the world Chihiro knows with its own rules she must understand if she wants to free her parents. The spirits immediately identify Chihiro by her (apparently repulsive) smell; the witch Yubaba expects her employees to follow a scrupulous code of etiquette while all unscrupulously pursue their own self-interests; and, when Chihiro rescues the spirit Haku, her one real friend in the spirit world, her acquaintance Lin can’t understand why Chihiro cares so much, requiring clarification from the spirit tending the boiler room: “[It’s] something you wouldn’t recognize. It’s called love.”

In each instance, from Tolkien to Miyazaki, woven among the obvious differences of physical appearance are differences of philosophy, mortality, and even morality that indicate the gulf between fairies, elves, spirits, and ordinary folk. Even Tolkien’s own Silmarillion, which primarily tells the story of the Elves, is haunted by the human presence from the beginning, with the first vision of the “Children of Illuvatar,” of the “Firstborn” (the Elves) and the “Followers” (the Men). The haunting melancholy of the Elves’ story comes, in a large part, from the contrast with the mortality of men, and the mystery surrounding their final fate, how their fate is tied to the created world, and can never fully remove themselves from it, while men can and do escape, albeit through death. Strange Magic, despite fine-tuning the physical differences among all its magical creatures, conspicuously lacks these smaller, almost metaphysical touches illustrating the “otherness” of its magical creatures.

A Shallow Secondary World

Lacking a sufficient entryway into its magical world, Strange Magic fails to create, in Tolkien’s words a viable “Secondary World.” According to Tolkien, a storyteller succeeds in his work when he establishes the world of his story and the “rules” of that world so thoroughly that we can accept it as another reality, a “sub-creation”: “What really happens is that the story-maker proves a successful ‘sub-creator.’ He makes a Secondary World which your mind can enter. Inside it, he relates what is ‘true’: it accords with the laws of that world. You, therefore, believe it, while you are “inside” it. The moment disbelief arises, the spell is broken; the magic, or rather the art, has failed” (132). Without a human or outsider presence, Strange Magic instead attempts to accomplish its world-building with a spoken prologue so trite, so inadequate, and so incoherent it deserves to be quoted in full:

This is a story about two kingdoms, side by side, but worlds apart. All along the border, magical flowers grew, primroses bloomed between light and shadow. They are used to make love potions. Because after all, everybody deserves to be loved.

What are these kingdoms? Why are they “worlds apart”? What does that even mean? Who–or what–inhabits them? Who makes the love potions, and why? How do the faceless, nameless inhabitants of these kingdoms understand love potions–are they an everyday reality, a social taboo, or a miracle? While some answers are given in short order, some, among the more important, we never receive. The success of a fairy-story depends on its ability to create a “Secondary World,” casting its spell in part by creating a consistent framework and remaining faithful to that given framework. Strange Magic fails not only to develop such a framework but to remain faithful to the vague rules established within its ill-conceived framework.

The exemplar of this failure to create rules and adhere to them is the love potion itself, a symbol of the film’s mishandling of genre leading to irretrievable flaws in execution. Like potion from its inspiration, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, the love potion’s basic function is to make its recipient fall in love with the first thing (man, beast, goblin) she sees. Midsummer follows this basic stricture and never deviates from it, creating outlandish comedic mishaps while maintaining the integrity of the magical world of the play.

Strange Magic expands on the idea, but without establishing its effects or general “rules.” Whereas the “rules” of the love potion in Midsummer are simple and almost ruthlessly logical, those of Strange Magic are more complex and less coherent. While the prologue, perhaps unwittingly, aligns the love potion with the moral that “everyone deserves to be loved,” the film attempts a more nuanced understanding of the potion’s primary effect. Dawn is doused with the love potion and falls in love with the Bog King; so far, makes sense. On further application, however, the device falls apart.

A key element of the story is the Bog King’s unexplained hatred of love and love potions, exemplified by the imprisonment of the Sugar Plum Fairy, creator of said love potions. When asked, the Sugar Plum Fairy reveals the Bog King’s hatred stems from the failure of the love potion to turn the heart of the girl he loved. In response to the Bog King using the story to justify himself, the Sugar Plum Fairy declares it failed because “she was in love with someone else.” As Marianne helpfully recapitulates for us, the antidote for the love potion is “real love”: “real love” overcomes the infatuation produced by the love potion. Well, why? How is a simple little potion so discerning? Even the most self-aware among us can struggle to determine whether our affection for someone is a selfless love or self-interested infatuation; from whence does the love potion derive this power to read souls?

A Happy Ending vs. Just an Ending

Without either clear rules for this world’s magic or sufficient character development, we come to Strange Magic’s most damning flaw wrought by its original sin: lack of satisfying payoff. Tolkien spends a significant amount of time on one of the most overlooked elements in the fairy story, the happy ending, or “eucatastrophe.” Tolkien claims that “all complete fairy-tales must have it…Tragedy is the true form of Drama, its highest function; but the opposite is true of Fairy-Story” (153). The “eucatastrophe”, he explains “is a sudden and miraculous grace, never to be counted on to recur. It does not deny the existence of dyscatastrophe, of sorrow and failure…it denies universal final defeat and in so far is evangelium, giving a fleeting glimpse of Joy, Joy beyond the walls of the world, poignant as grief” (153).

Were there no magical elements in a fairy story, most of them would end in tragedy. In Snow White, for instance, it seems the wicked queen has won and Snow White is dead. In Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings, it seems at the bitter end Frodo will not cast the Ring into Mount Doom and the quest is irrevocably doomed. But then, events take a sudden “turn,” a joyful version of Aristotle’s peripeteia, wholly unexpected but not unprepared for. When all seems utterly bleak and hopeless, when despair and grim acceptance seem the only natural options, the characters are visited by a “sudden and miraculous grace,” not only delivering them from their tragic circumstances, but delivering them to circumstances better than they ever dared hope for: “It is the mark of a good fairy-story…that however wild its events or terrible its adventures, it can give to child or man that hears it, when the ‘turn’ comes, a catch of the breath, a beat and lifting of the heart, near to (or indeed accompanied by) tears” (154). Snow White not only is rescued from death, but from the thrall of her wicked stepmother, to live happily ever after with the King’s Son. Gollum, in his attempt to wrest the Ring from Frodo, unwittingly destroys it himself, and accomplishes more than the Fellowship dared hope possible.

Unlike a deus ex machina, the resolution of the fairy story, though an unexpected grace, is hinted at throughout the narrative, proceeding organically from the framework of the story. Thus, the destruction of the Ring, at the hands of the least likely candidate, is set up and hinted at with Frodo and Gandalf’s conversation about the Ring and Gollum at the beginning of The Fellowship of the Ring. A deus ex machina is tacked on, comes from nowhere, and reeks of lazy writing. Eucatastrophe is hard, a deus ex machina is easy.

The conclusion of Strange Magic, though it attempts the former, resembles the latter. Throughout the film suffers from a palpable lack of peril, with the only real crisis, Dawn’s kidnapping, played more for laughs than suspense, and Roland’s attack on the Bog King’s lair coming too late to generate any real sense of stakes. Our would-be triumphant conclusion is further muddled by the earlier lack of clarity regarding the workings of the love potion. At the conclusion of the film, Roland attempts to take his revenge by dousing Marianne with the love potion, only to receive a punch in the jaw from an unaffected Marianne. And why did the potion fail to enchant her? Supposedly, because she is “already in love” with someone else; namely, the Bog King.

Part of this ending is not magical at all, relying on withheld information rather than actual suspense. While a precedent has been set for the other part of this ending, it lacks any real effect due to the earlier failure of world-building and character work. By this point, Marianne and the Bog King have spent barely twenty-four hours in each other’s company and despised each other for two-thirds of that time. They don’t meet until half-way through the film and have one love duet before the inevitable third-act misunderstanding. Who is to say this is any different from infatuation? What makes this “real” love? According to Strange Magic, what even is love? Why is Marianne and the Bog King singing and making googly eyes at each other any “deeper” or “truer” than Dawn’s earlier flirtations with the young fairy men?

The film never differentiates the different kinds of love, despite the importance of their distinction to the central theme and conflict of the story. In the end, we realize the film has failed to define its fundamental preoccupation and theme, making the whole thing seem like so much wasted time. By failing to address these fundamental questions, Strange Magic undermines its own conclusion, and its ending seems an afterthought, an unsatisfying and nonsensical one at that.

In failing to understand its genre, Strange Magic fails to accomplish the “highest function”, of its purported genre, the fairy tale. By failing to provide a human presence within this world, it forgets to properly introduce its world. By forgetting to properly introduce its world, it neglects to establish “rules” for its world. By neglecting to establish “rules” for its world, it miscarries its own conclusion, failing to fulfill the “highest function” of a fairy tale, the happy ending. These flaws in execution can be traced to this initial failure, this original sin: making a “fairy story” about fairies. Strange Magic never grasped the fundamentals of its genre, and so floundered when it came to constructing a compelling or coherent story within that genre. Perhaps, then, Strange Magic was doomed from the outset.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

The problem with the story is that it is not really there. Bare-cones of some Shakespeare is used as a framing device to give magical creatures the opportunity to sing ’60s and ’70s pop songs. It’s basically a karaoke machine of a movie, with heavily rendered & animated visuals.

Thank you for writing this article. I had the pleasure of working in the past with a lot of the people involved in this movie. They are EXTREMELY talented, and I am proud to have had them as colleagues.

I wanted to be an animator and fell through in school 🙁 But this movie is my all time fav more than Frozen..

Christ on a cracker. I am a big Disneyphile, a Star Wars fan from about 1980, and I follow the latest animated releases (relatively) closely, but I never, ever heard of this movie until JUST NOW. I suppose that goes to show what a bomb it was…

It came and went from theaters towards the last week of January few years back without much fanfare or the usual giant promotional push that most animated films tend to get. I had no idea that it had been in the works for so long or that it was something that took forever to get made—I honestly believed it to be a quick cheapie when it came out that somehow got a theatrical release because it was winter, and why not?

I’m genuinely surprised to see it being covered here, but glad I ended up reading this article which is quite better than the film. 🙂

If you want a weird Lucas movie from before he went crazy Twice upon a time is pretty weird. I haven’t actually seen it since finding a VHS copy at the library when I was a wee lad so it’s possible it might actually just suck.

I own Twice Upon a Time on VHS. I should get it transferred to DVD or just ripped to digital if I ever expect to see it again.

It’s on DVD now; the disc includes both versions. Yes, there were two versions of Twice Upon A Time; the clean version and the gag dub where the villain swore his head off. It got out and was the version shown by HBO.

Delighted to see this article go live. You put a lot of work into it and it’s paid off. Great work and fun to read. Thanks

I’m so glad to see this published! You should be really proud of all of your hard work. I like how you related your thesis to The Lord of the Rings and A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Fairy tales are so intriguing! To call Strange Magic one is, I agree, quite a stretch. Anyways, this is a fantastic read, thank you for sharing this with us!

“In each instance, from Tolkien to Miyazaki, woven among the obvious differences of physical appearance are differences of philosophy, mortality, and even morality that indicate the gulf between fairies, elves, spirits, and ordinary folk.” That line really got me. Faerie’s nature is an “otherness” and to not portray them as “other” really removes any wonder from their actions or choices. This piece really articulates that well without coming across as overly-critical, which I appreciate.

I’m surprised George Lucas did an animated movie I always thought he was a sci fi kind of guy.

I will never understand what happen to the man who made American graffiti.

That movie is made with nothing but actual skill.

Everything else he’s had that’s successful is the byproduct of a multitude of other people but American graffiti is such a singular vision, it’s mind boggling.

Agreed, and I’m slightly softer on Lucas than others are (largely because I’m not partcularly invested in Star Wars, but also because I can’t hate a Bruce Conner fan), but by and large, I think that the best thing Lucas could have is a collaborator – a Walter Murch, Gary Kurtz, or non-accommodating Spielberg to make him toe some sort of line. Because when he’s on his own, he leaps for indulgence and self-sabotage.

I honestly think all of his good fortune came from his ex wife Marcia lucas. Even mark hamill said she was the unsung hero of star wars.

Oh yeah, THIS movie. Can’t say I blame Lucas for trying to make something for girls to like.

IMO Into the Woods was much, MUCH better than Strange Magic. It featured songs that actually made sense and didn’t read like a bizarre, stilted cover video, and a fresh parody of fairy tales instead of playing the tropes badly.

There was a winceworthy /clumsy/ girl who then switches to the spurned bad girl trope. No in between, no real meshing of the two. Love can clearly completely change personality and interests. It would have been more forgivable if she’d been interested in fighting at all BEFORE she got dumped.

Then there was her sister. A flat character if I ever saw one. She provided support for her sister and angst and a trophy for the gnome guy without ever becoming her own person. She clearly only cares about guys, and if she isn’t interested in someone she will discover this interest later sobbing into their arms. I mean unrequited love sucks but that’s no excuse to turn the friend zone (a nice place really, friends are awesome) into Tru Luv. It’s a caricature of a lady, not an actual person.

The villain. Pretty unreasonable, had a funny plot about his mom trying to hook him up, imprisoned the love fairy for her love potion not working. And love potions being used to totally subvert free will is never actually examined, and is a valid way for everyone to find love, unless the plot says otherwise.

There’s the massive plot hole of why the dickish ex even wants an army. Who would he fight? What would he gain??? Jesus.

The animation was beautiful! Sadly there’s the ever so popular trope of girl armor showing more skin instead of being cool. And the girl’s love interests were both pretty ugly, while the girls were both pretty and kinda generic in looks. While there’s nothing wrong with that it’s something I’ve seen again and again and again. And girls like their love interests pretty.

I did like the scenes where the heroine/villain were very similar, but that doesn’t spell out true love.

It has its flaws and there were times when I was thinking of tweaks and things that might make it a little better/tighter, but overall I really enjoyed it despite those things.

I was not expecting to like it so much, and I’m glad it gave me a pleasant surprise. Predictable? Yeah… but I’m a sucker for these things (animated romantic jukebox musicals, I guess).

My 12 year old daughter was cringing through the whole movie- and I think it ruined Fairies for my 7 year old… We were all relieved when the torture was over!

Nice read! I saw the movie. It was beautifully made. The animation was beyond superb. The story was interesting. The characters were oddly annoying despite the amazing animation. But the movie as a whole was terribly hard for me to watch. For me it was the fact that it was a heavy musical for which I was unprepared. I’m a 60 year old guy, but I could not tolerate old tired 60’s hits sung by the actors in the style of a musical like Grease. And not just a few. This was a Musical with a capital “M”. If you love musicals a lot, and still love 60’s hits, see this movie. There was a lot to love about this animation. But please don’t make me watch it again.

I saw this twice. Once in the theatres because it was movie day with the kids and it was the only age appropriate thing on, and once on Netflix because… I have no excuse.

Disney shafted the hell out of this movie. Shame, I bet if it had more advertising it would’ve at least made a couple million more, which wouldn’t save it but would help heal the wounds a bit.

I had no idea it was released.

What I wonder, why is Disney continuing to waste money (and time) on projects they know is not going to generate back strong returns or interest audiences? Not just with this film, but with the Planes franchise, and even when they did Winnie the Pooh as their last hand drawn animated feature film? Seriously, there are better things they can devote their time to, and push it further…maybe had this been a direct to DVD project, might not be as a bomber as in the theaters…but even I cannot promise that.

My newspaper didn’t even give it a review–it must have either been that bad–prevented from being reviewed by critics or actually forgotten.

You know… On one hand the animators did a awesome job and it looks gorgeous but on the other hand this movie just made me cringe from the trailer’s dialogue. And if I didn’t know that Strange Magic was under Disney and Lucas I would’ve assumed it was a movie to promote a World of Warcraft type of franchise. I think I will stick to reading this post.

Enjoyable film with an old-fashioned vibe, probably best for those who appreciate musicals.

Disney treated the film to ensure it would bomb… Disney tries to ensure the failure of any non-Disney or non-Pixar animated film that they are involved in distributing.

This movie wasnät failing because of “Warner Bros. flubbing Iron Giant” style marketing incompetance, it failed because it would at best appeal to a very narrow market IF it were done well, and apparently it failed to appeal even to that niche. No one wants to see “Ferngully+Glee In The Uncanny Valley” and the lack of marketing and cross-promotion was probably a wise move by Disney to avoid tainting their reputation unfairly by nominal association with something on at Burbank or Emeryville had anything to do with. This movie is just another piece of “what happened to you man, you used to be cool” kindling to throw on the George Lucas bonfire.

I didn’t hear anything about this until it was close to Christmas time, and even, I didn’t feel too strongly about this project. The premise was not detailed strongly in the promotions they had.

I actually liked the film’s take on the “Beauty and the Beast” premise. That coulld’ve been a decent movie. But the idea is fleshed out by a badly written screenplay filled with bad jokes and one-dimensional characterization. The Bog King was the only character with depth; everyone else was a cliche. And I’m still baffled with the premise of performing pop songs we’ve all heard a zillion times in a setting where they’re completely out of context. That sure didn’t work for “Sgt. Pepper” either.

Thanks, I’m looking forward to seeing it. I try to see all animated films, good or bad. As an animator there’s a chance to learn from every release.

After hearing nothing about it and doing some reading up on it, I was pleasantly surprised.

it’s a copy of Shreck kind of story and format… but with more reallistic models and dramatic light :/

Great discussion with some strong analysis that ties into the roots of such texts that want to be built of the backbone of traditional story telling. However, really not a surprise only by following the MOST literally hero’s journey was the original Star Wars a success.

After watching this movie with an audience of adolescents, we discussed what they liked most about it. All of them agreed that what they liked was that the movie encourages us to look beyond appearances and see what’s really in a person’s (or fairy’s) heart.

While I appreciated that perspective, it also caused me to realize that really the only thing the audience remembered about the film was something that had nothing to do with the world the producers attempted to create in the film. The same message could have been conveyed just as interestingly through a narrative about humans. It seems that there was no real purpose in creating the magical world except for adding interest in terms of setting and animation.

An interesting article on a movie I’m not familiar with, so now I need to see it. Sometimes that’s what you want from a well written article: Increasing curiosity in a movie or a book.

I always want to try different films, horror movies lover <3 anyone direct me to some of extreme horror movies you know? thanks

I always enjoy reading essays that delve into why a film is bad. I saw this one and didn’t give it a second thought, but you’re absolutely right on all counts.

Regarding Tolkien’s quote about fairytales, it also changes an interpretation of Spencer’s “The Farie Queen”.

I applaud Lucas for making this movie is the best movie I have ever seen. I watched it over 50 times I watched it again today, so thank you so much for making this movie. Wish you would make more.

I skim read your article….will do it justice when I have finished the comment.In this age…we are very keen on Science and empirical evidence…such an attitude will not take us into the realms of the invisible worlds.Whether invisible realms exist or not is not something we can prove or disprove….and if we do have a brush with the world of faerie…we will probably dismiss it as an illusion or that variety of “weed”… or some bad or overly strong hallucigen.Magic…is the manipulation of primal forces by an adept….whatever the title….mage ..magician….warlock….wizard….soceror…it is not meaureable by our” science”….but it is necessary to entrance into other dimensions….ignorance is the bane of humanity….knowledge is vital then comes strength…the strength to overcome egotistical drives and raise the level of our beingsAnyway I enjoyed your article…am a believer in the eternal struggle between good and evil…in realms beyond our human level or plane…I had my brush with the faerie….I am an old man now…can’t wait for the next adventure….though I doubt I’ll remember this….that is just the way it is.Thanks for your article.Richard.