The Great Screen Impressionists, Part Two: The Cinematic Experience

While the first part of this study discussed the various types of comedic impressions found on television, the following will focus on those actors and actresses who exemplify what it is to perfect the dramatic impression, many of whom have received the ultimate acting accolade, an Oscar, for their efforts. The Oscars are not the most accurate way to judge cinematic talent; indeed it is clear that for every deserved win by Cate Blanchett, for example, there is a puzzling success for Marisa Tomei. The very fact that Leo Dicaprio does not hold an Oscar is a sin unto itself, considering how many breathtaking movies he has been a key part of. I wonder sometimes, is he going to be the Peter O’Toole of our generation?

What is most evident, however, is that the Oscars love a historical impression. Critics love a historical film. It is difficult to envision more than two years going by at the Oscars without an actor or actress nominated for playing someone else. While this year Wolf of Wall Street was a prime player, as was Dallas Buyers Club, previous years have seen Elizabeth, Shakespeare in Love, and Midnight in Paris snag major acting, directing and a whole host of other awards.

These films are not carried on the back of actors. They come about with the dedicated work of cinematographers, costume and set designers, editors, production assistants and CGI gurus, not to mention screenwriters, directors and producers. However, one bad actor, one bad impression, can utterly ruin a film. If your lead is wrong, if your love interest is flat and useless, it doesn’t matter how beautiful your scenery is, people will notice. Audiences aren’t that stupid (most of the time), and as I will talk about later, they know when someone doesn’t belong.

So, what makes a great historical impression? What makes certain actors and actresses streets ahead of the competition in terms of likeability, authenticity and sheer entertainment value? It would be easy to say it comes down to direction and costume, but the people on this list need to gaudy jewels or crowns to be their characters, they simply are (to sound terribly pretentious). I think it is a number of aspects, each of which I have detailed below, exemplified by one key actor/actress. I have limited this list to those that portray significantly famous historical entities, rather than those created from fiction or are the stuff of autobiographies, not because they are in any way better, critically, but because they more clearly emphasise the points I attempt to clarify.

Cate Blanchett: Majesty and the ‘Quiet Moment’

Great impressions often happen not at a climactic moment, with guns blazing and trumpets blaring, but in a second of quiet, in the calm before the storm. Cate Blanchett is not only an accomplished actress, but one of the finest impressionists of her generation. Aside from her Elizabeth, which we will look at in a moment, her nuanced takes on Katherine Hepburn and Bob Dylan are superb. In Aviator, Blanchett seamlessly wove her character into the narrative, bringing the bombastic and oft over-exaggerated character of Hepburn to heel.

In Elizabeth, Blanchett has plenty of opportunities to chew the scenery. However, as much as she allows costume and set to speak for her in times of pomp and circumstance, it is her quiet intensity in scenes not well known to historians that show her prowess as an actress and impressionist. Elizabeth Tudor is lauded as an English heroine, as the herald of the Golden Age- and she deserves each one of those accolades. However, she was also flighty, flirtatious, jealous, clever, curious and sarcastic: elements that many other actors fail to bring out. When famous icons are filmed, it is commonsense to focus on, or build to, climactic moments in their lives. However, far too many actors and filmmakers seem to believe that these moments define us, that they are who we are meant to be.

In one memorable scene, Elizabeth is about to be taken by the royal Guard to be imprisoned at the Tower. Rather than portraying a false sense of bravado that has been pushed upon Elizabeth’s historical character, you can practically feel the fear coming off her in waves. She shudders and shakes, finding courage only in the touch of long-time confidante Robert Dudley. Perhaps it would be truer to the collective memory of Elizabeth if she was constantly brave, constantly courageous and true, but Blanchett’s terror rings far truer, and connects the viewer far more closely to the story.

Without these quiet moments, historical domain characters can appear no more three dimensional than the history books in which they star, many of which showing far more well rounded visions than those that make it to screen. In Blanchett’s capable hands, Elizabeth is a well-rounded human being, capable of terror, majesty and childish jealousy within the space of a breath. It is in these quiet moments, rather than those of ceremony, where her portrayal shines brightest.

Helen Mirren: Respect with Truth

I used to be quite the improvisation aficionado. In my schooldays, I loved pretending to be someone or something that I was not, whether that was a role in the spotlight or as a particularly effervescent anthropomorphic lamp. I did notice, however, that during my theatre sports years, the most difficult people to impersonate were those that were still alive. Let’s forget for a moment that those impersonated might feel offended by the critique, as in my case I highly doubt famous celebrities saw my school improv performances, and focus on the audience.

What happens when the impersonated is highly valued by your audience? In Australia, where I hail from, this isn’t too much of an issue considering our laid back attitudes towards politicians and celebrities. However, one trip across the pond to the USA and you can see a far stricter dichotomy between what is ‘okay’ to satire and what isn’t. Shows like Saturday Night Live forever straddle this line between toothless and inoffensive, and biting and slightly cruel. It seems that, in many cases, we can either completely satirise and expose the underbelly of humanity, or we can present a sepia-toned and squeaky clean representation of their life that has no relevance to our modern society. Unless, of course, you are brilliant. Unless you are Helen Mirren.

The Queen wasn’t a perfect movie. I felt that, at times, it dragged slowly through ceremony and shied away from Charles’ role in those tragic hours before and after Diana’s accident. However, I believe Mirren deserved every accolade she received for her reserved, and yet somehow well-rounded, portrayal of Elizabeth II. Like Blanchett, Mirren finds her character’s humanity in small, quiet moments. There is no great breakdown, no moment when her seeming-impenetrable façade shatters, but we do see cracks. Like old, tired foundation, we can see slivers of what lurks underneath the crown. However, unlike Blanchett, Mirren has to consider another, difficult layer- that the character she portrays is still living, and while not universally loved, has a highly positive reputation. What about those who want to see a more relatable monarch, regardless of whether that is who she truly is or was? What about those who believe she had a role in her ex-daughter-in-law’s death? How do you please both monarchists and republicans alike?

Navigating these waters was never going to be easy, but I think Mirren does it with the practiced ease of an Olympian. Never leaning too far on either side, Mirren’s Elizabeth is prim, tetchy, and altogether aware of her high status, as shown quite humorously in her interactions with Michael Sheen’s Tony Blair (yet another brilliant impressionist). However, she genuinely cares not only for her family, but also for her country. The moment when she hears of the fatal accident is near-heartbreaking in its simplicity, as are her familial interactions afterward. She is cold and detached in her address to the nation, but not only was Mirren working from real stock-footage, she was staying true to the reserved character she was playing. After all, when have we ever seen a broken Elizabeth Windsor?

There is a lesson to be learned here. If you are going to portray someone who is still alive, there is no point in doing so if you are not prepared to show them, perhaps not as they truly are, but as an amalgam of what they seem.

Midnight in Paris: Fill Your Movie With The Best

It doesn’t matter how brilliant your lead is, I believe that if they are surrounded by sub-par actors, the movie will suffer. Imagine The Queen without Michael Sheen, or The King’s Speech without Helena Bonham-Carter; neither are the focus of, nor do they make the films, but they are imperative to creating a strong, authentic atmosphere. Authenticity is not solely the product or realm of costume and set designers, the casting department also has a clear role to play. Like it or not, there are certain actors that do not belong in period or historical film, mostly because they are simply too ‘of the moment’. While not strictly in the realm of films I am discussing, the most prominent example I can think of is the inclusion of Shia LaBeouf in the near-universally panned Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull. Look, the film had more problems that just casting (ALIENS), but could any of you really picture LaBeouf as a late 1950’s greaser? So, in order for a film not to be LaBeoufed, as we shall not call it, every actor chosen must suit the tone and the time period down to their soul. I can think of no greater example of this than Midnight in Paris.

For the uninitiated, Midnight in Paris takes place in two (later three and, briefly, four) different time periods, as Wilson’s stalled American author time-travels from modern day to 1920’s Paris. The film succeeds in making the classic American Wilson stand out in the 1920’s crowd due to its effortless recreation of the time period. Unlike the champagne soaked nightmare that was The Great Gatsby, Midnight (in my opinion), emphasises the loose living and let-the-good-times-roll attitude of the era without resorting to cheap gimmickry or unnecessary flesh flash. The actors who populate the world are no less authentic, with standouts (amongst a strong cast) being Tom Hiddleston (F. Scott Fitzgerald), Alison Pill (Zelda Fitzgerald) and Adrien Brody (Salvador Dali).

I will have you know that the reason I focus on Hiddleston rather than Corey Stoll’s superb Ernest Hemingway is only 20% because of the former’s impeccable cheekbones. Stoll (deservedly) received accolades for his portrayal of the troubled Hemingway, but it is Hiddleston’s understated performance that blows me away every time. With less than 10 minutes of screen time, he highlights the character’s struggle with his writing and legacy without directly having the reference either. He is assisted in this by Pill, whose troubled Zelda steals every scene she is in, hiding her deep internal struggle with booze and outlandish behaviour. She is a breath of fresh air in a film that often trends towards pushing non-leading women into the angel/whore archetype. Finally, I have to mention Brody, whose one scene as Dali not only encapsulates the latter’s twisted, colourful, absolutely mental outlook on life, but does so without becoming a caricature of himself. I won’t spoil his scene, but I would watch a movie that was purely him and Wilson discussing art . . . and I am not an ‘art’ person.

Without these actors, without these characters, these movies fail. It is a big call to make, but I can’t help but think that setting becomes little but window-dressing without the right people do make it come alive. Great historical films practically breathe with you, and invite you into their world with every intake of air. Midnight in Paris may not be perfect, but it is certainly great.

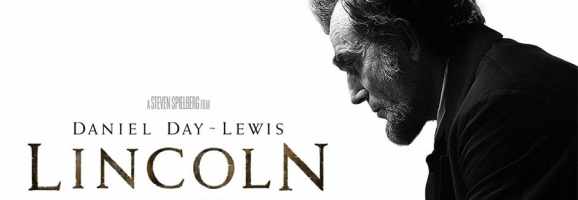

When in Doubt: Daniel Day-Lewis

I’ve never met a person with a bad comment about Daniel Day-Lewis (Or DD-L, as nobody calls him). He is one of those people who it is very difficult to hate, or criticise. Some manage to do it of course, by nitpicking and exposing their pedantry to the world, but all-in-all his historical performances tend to be near-flawless, predominantly due to the level of dedication he affords to each role.

Not many men could get away with playing Abraham Lincoln. Something about the beard and stovepipe had scream humorous, seems cliché. For many men, the role would be nothing more than the costume and some soapbox preaching about slavery. Not for Day-Lewis. He threw himself into the role with aplomb, humanising the man until one almost forgot his fame and focused on the person behind ‘four-score and twenty’. Was it the most exciting movie? No particularly. However, I can’t find fault with his personal performance.

This type of focused control is brought to each of the historical roles he has played, from his mad butcher in Gangs of New York, to Christy Brown in My Left Foot, has left him the pinnacle for what method acting is all about. Though not strictly historical drama per say (even though he was a real person), his John Proctor near singlehandedly saved The Crucible from being unwatchable. I would argue that it is his presence which lends the air of credibility the film so sorely lacks.

I just get the feeling that if Day-Lewis was case as the back half of a donkey in a Christmas play, he would do months of preparation living as a donkey. He might even get the tail surgically applied. Thus, the final point about historical drama casting and impressions? If in doubt, get Daniel Day-Lewis. Playing George Washington? Day-Lewis. King Henry VII? Day-Lewis. Emmeline Pankhurst? Screw it, Day-Lewis.

There we have four key actors and the primary methods through which they create the authenticity and believability of their portrayals. It is, of course, by no means a comprehensive list, instead working more as a guide, or a list of attributes. How could any list of impressions that does not include Colin Firth, Geoffrey Rush or the late Philip Seymour Hoffman be truly complete? Did I miss any egregious examples?

What do you think? Leave a comment.

In my opinion, “Elizabeth” is in the top 10 female performances of all time in the history of cinema. It’s one of those larger-than-life performances that fully absorb you as a viewer. Cate as the great “Queen Bess” simply must be seen to be believed – and enjoyed. For me, every time I watch the movie ( and it happened quite a lot in the last sixteen years ) it is almost like a religious experience to me ( and I’m not a very religious person ), literally something that defies any rational discourse.

When I first saw trailer for “Elizabeth” back in 1998 I was like: ” What ? This is biopic about “Gloriana” and they choose this Aussie blonde nobody ? Are you kidding me ? Seriously ? Wow, this movie is going to €%&/.” I was very disappointed because Elizabeth I was always one of my favorite historical figures and now, I didn’t even wanted to see it. But later that year, I went in the theater without great expectations and My God…well, the rest is history. Literally overnight, Cate Blanchett became my favorite actress and it continues to this day. It’s impossible to describe what she has done with the role in just two hours. So many great scenes: her dance with Dudley on the beautiful David Hirschfilder’s score, her interrogation by Mary, her immortal words – ” This is the Lord’s doing and it is marvelous in our eyes”, volta, her speech to the lords and bishops, “He shall be kept alive to always remind me of how close I came to danger” with Elgar’s “Nimrod” in the background…

Of course, “Elizabeth” isn’t without flaws – anyone who has studied that part of history will notice certain historical inaccuracies ( film covers the period from 1554 to 1572 and yet, it seems to have been only a few years, Dudley was never a traitor, Norfolk was never that evil and scheming and he was even younger than Elizabeth, Duke of Anjou wasn’t transvestite etc, etc…) but thanks to Cate’s incredible performance and Kapur’s inspired direction movie works in the best possible way ( which is not a case with the sequel ).

Everything in “Elizabeth” is delightful: the sets, costumes, photography, subtle but at the same time epic direction…very compelling and powerfully irresistible. And yes – this film was Cate Blanchett’s introduction to the world. And that is enough to gain cult status.

I completely agree, ‘Elizabeth’ is completely captivating and Blanchett’s performance is so elegant. I’d watch it again and again.

I appreciated the acting of Helen Mirren and I wasn’t at all surprised to see that she received the Oscar for her performance. She was excellent. But wow, the movie wasn’t good.

Don’t forget Martin Sheen!

Cate totally disappears in her characters. I always forget it’s her the moment she’s on screen. She makes her personality transparent and you can only see that of the character. She’s not a chameleon only in the sense of physical transformation. She’s even better in the emotional one. Not even Meryl manages to achieve that in such a grade for me. When I see Meryl, I always see Meryl first and then after some point I get into the character, but never that instantly and that deep as I do with Cate.

I was Martin Scorsese’s assistant during “Gangs Of new York” so, naturally, I had very close contact with Daniel. I loved him, I loved his approach to his craft and to the people around him. Also, he gave my mother such a warm hug when he met her that she has carried his warmth ever since.

I loved DDL’s Lincoln performance. I know I love to compare Daniel to the 50s method actors and I thought it was a very Clift-performance. If “My Left Foot” was his Brando performance – insecure, angry, individual trying to articulate and express himself. And “In the Name of the Father” was his James Dean performance – immature, fidgety teenager turns turns into a man. His Lincoln performance was quiet, subtle, the acting was centred in the eyes. His Lincoln evolves and deteriorates (though I’ve read people thought the character was static and Tommy Lee Jones had more an arc). He seems trapped. He looks tortured. He radiates a twistedness. There’s a certain mental heaviness that appears to press on his eyeslids. He’s a man with a lot on his mind. He’s always sitting or reclining, meditating on some complex moral dilemma. He’s a shock absorber for society’s insensitivities. He looks so broken and ill at ease in his body.

There’s another similarity in that alot of Clift characters – they’re rebels who stand out in a lonely crowd, forced into action at a time of great anxiety and uncertainty. Seven of his films feature some form of conflagration (the American Civil War in Raintree County, the Second World War in From Here to Eternity, the aftermath of that war in Judgement at Nuremberg, etc).

Not only that but he’s incredibly generous with the other actors – another Clift trait. Clift certainly helped Burt Lancaster, Frank Sinatra to up there game and gave them plenty of space to shine.

Excellent points about Lincoln and it being more Clift-esgue. I like that. I think LIncoln, the character, has mostly mini-arcs. The biggest arc is his decision to support the amendment and it happens in the first five minutes. He develops a goal that came as a result of a dream (his boat dream which convinced him that his destiny was to man the ship of this societal movement–to both go with the flow and help the boat move towards it destination). Its a resignation to his duty. But that being said, there are certainly moments when he feels the loneliness and burden of that duty, when he exhibits doubt and worry about his decisions. The two mini-arcs that stand out..one is shown during the Euclid scene. He almost lets the peace commissioners come to washington but when he starts talking about whether he really has free will and about the natural order of things as exemplified in the euclid he decides to put the ending of slavery above the ending of war because that’s just the way it needs to be.. This is tough decision even though I am not sure Lincoln even thinks its his decision (its fate, destiny, or God’s will and he’s just the tool. Or at least that how he copes with the guilt associated with prolonging a war) This destiny was written 2000 years ago and he is just playing his required part of that..) Another mini-arc actually takes place in his argument with his wife..maybe arc is the wrong word. But the character decides to open up a bit about the mourning of his son to his wife. that moved me. When people say that the personal stuff doesn’t fit into the movie, I think they are missing the point a bit. To be this instrument that Lincoln is, to be a leader, one has to be self-contained and a little removed (objective as possible). This is a necessity but unfortunately it makes a personal life difficult. Lincoln is not lacking warmth or even a longing to be with people (his bedtime chats with aids and telegraph officers, his affection with his youngest son and even his wife in the carriage scene prove this) but he has to withdraw as quickly as he connects with people. He ultimately has to make these important decisions by himself and he can’t wallow in his sadness too long or it will render him dysfuncational.. He is a lonely man and carries his burdens alone but that’s the way it has to be (as he explains to his wife after their fight). A simple arc is not provided but uneasiness, guilt (over the casulties) and internal conflict are and those things don’t go away. Had LIncoln lived into the reconstruction days, he would have still been burdened. Lincoln doesn’t change as much as he is trying to stay on course and remain optimistic despite worries, doubts and even an impatience over the longevity of the war.)

I do honestly think his work (and work ethic) is informed by Clift more than the others. There’s that interview where he mentions thinking there’s something special and watchable about Clift. He mentioned Charles Laughton and possibly Clint Eastwood as well.

I noticed bits of Clint Eastwood in “There Will Be Blood”. He has the same steady, purposeful walk.

On DiCaprio – he’s a talented, charismatic movie star, who, by and large (with a couple of exceptions) can’t really disappear inside his characters, regardless of how diverse they are on paper. It is partly to do with his voice and movie star persona – an inability to largely transform it, not through costume and wigs but through the schizophrenic process of ultimately dislocating your self from the character and speaking, doing, emoting as them in the context of the story as opposed to doing (whether intentionally or not), for instance, a version of you through them/you speaking through the character (and it’s not necessarily a bad thing, some people prefer that kind of actor, and many actors considered great, including some of my favorites, share something of that) – granted, not many have that “schizophrenic” ability anyway. By consequence, he becomes quite repetitive, in emotive scenes for instance, and though sometimes the phrase is misused, that’s when you hear variations of ‘playing himself’. He tries really hard though and has succeeded in the past, and that is at least commendable. On the flip side, DiCaprio isn’t a character actor, something he clearly tries to be and thinks he is, and so the ‘trying hard’ only exacerbates his relative shortcomings on screen. But hey, no actor is perfect in their job.

Very elaborate take on this perspective. Good work.

good job

Helen Mirren is so good. Her performance in the Cook, the Thief, His Wife, and Her Lover is phenomenal if you can stomach the film.

Great article. Interesting that you use Blanchett’s performance in ‘Elizabeth’ here and I do agree with you, but her return to that role in ‘Elizabeth: The Golden Age’ is scenery chewing at its most obnoxious. I often wonder what she was thinking when she even agreed to do the sequel.

The Elizabeth portrayed by Blanchette also is consistent with accounts of what the real-life Elizabeth was like.