The Idol Phenomenon in Japan and Anime

“Magazines, radio, above all television: in whatever direction one turns, the barely (and thus ambiguously) pubescent woman is there both to promote products and purchase them, to excite the consumer and herself be thrilled by the flurry of goods and services that circulate like toys around her.” – John Whittier Treat (1993, as cited in Galbraith & Karlin, 2012).

Jpop is a broad term that refers to Japanese pop music, or even popular Japanese music (Covington, 2014). As much fun as a catchy, silly pop song is, a more interesting phenomenon in Japan is the idea of “idol pop”, music by pop idols, sometimes called aidoru. They are distinguished from normal pop singers since they are a product of recruitment agencies and have a large focus on promotion. Although idols can exist and function outside of an agency, the most successful ones have a contract with a company (Galbraith & Karlin, 2012).

In its humble beginnings it nurtured boy bands, but nowadays the trend favors females (Covington, 2014). The mounting popularity of aidoru has coincided with similar ‘cute’ media in Japan like manga, anime, K-pop and hot spots for these forms of entertainment like in Akihabara and Shibuya. The trend of adorableness has even spawned its own set of Japanese buzzwords to define sexy-cute, classy-cute and trendy-cute (Galbraith & Karlin, 2012).

Nakamori argued that the phenomenon has grown to such an extent that idols are the main face of Japanese culture. In recent years this phenomenon has gained the interest of scholars for their profitability, as Japan is one of the world’s top media consumers. CDs for these idol groups sell even when file sharing and music rental services are at an all time high (Calbraith & Karlin, 2012), indicating that the success and over-saturation of idols may be a strike of marketing brilliance. This article aims to examine the history of idols, their function and their integration into anime.

1971 is considered the beginning of the boom with the first idol group Sannin Musume (Kimura, 2007, as cited in Galbraith & Karlin, 2012). The first idol group recruitment agency was Johny & Associates in 1963 and these were aimed toward males as well as females (Covington, 2014). The timing was perfect since half of Japanese households had a television in the 1960s. One popular all-male group called Arashi made their start with this company in 1999 and are still going strong (Covington, 2014). Another hit male idol boy band is SMAP who are also still producing hit singles after their debut, matching the success of the Backstreet Boys but managing to stay big for longer (Bennett, 2012).

From the 70s the output of artists was rapid. In the 80’s there were so many idol groups making debuts in Japan that the decade is often referred to as the “Golden age of Idols”, with the artists staying relevant by making numerous television, commercial and movie appearances. It is through idol groups that music was used for television theme songs and in short TV commercials (Stevens, 2011, as cited in Galbraith & Karlin, 2012), an advertising technique which has crossed over into anime as well. In the West some of these marketing tactics were used for the Spice Girls, Girls Aloud and Britney Spears (Campion, 2005), so the thinking behind it is not as alien as one may think. With the careful placement of idols that infiltrate every aspect of the media, Japan’s entertainment industry can be seen as more than the sum of its parts. The concepts of celebrities, spectacle and music all link together and influence each other in a circular pattern, only emphasized further by idol appearances being over analysed by news programs in a political comedy type fashion.

Since the mid 90s the popularity of idols exploded and hasn’t slowed down, with Tokyo holding their first idol festival in 2010. For the dual relationship between idols and advertising this decade has been labelled as “hyper-capitalist” (Galbraith & Karlin, 2012). Below is one of the more colorful and creative AKB48 videos which could be a giant product placement for eating more vegetables. It is a prime example of the group’s identifying features – lots of attractive young girls wearing cute clothes, dancing happily and singing to bubblegum pop similar to Billie Piper, S Club 7 or Hilary Duff.

Producer Yasushi Akimoto was inspired to form the gigantic over 130 member female group AKB48 out of the idea “idols you can meet”. The large number of members means the subgroups can perform in multiple areas at once (Covington, 2014), the name being derived from their beginnings in Akihabara. They have been going strong since 2005, although their existence isn’t just confined to a CD or their songs playing over the radio. AK48 is “integrated into the everyday life of Japan today”, with their personalities appearing in commercials, news segments, as hosts of television shows, on advertisements in trains and magazine covers (Galbraith & Karlin, 2012). They are an inescapable encounter in a Japanese person’s day.

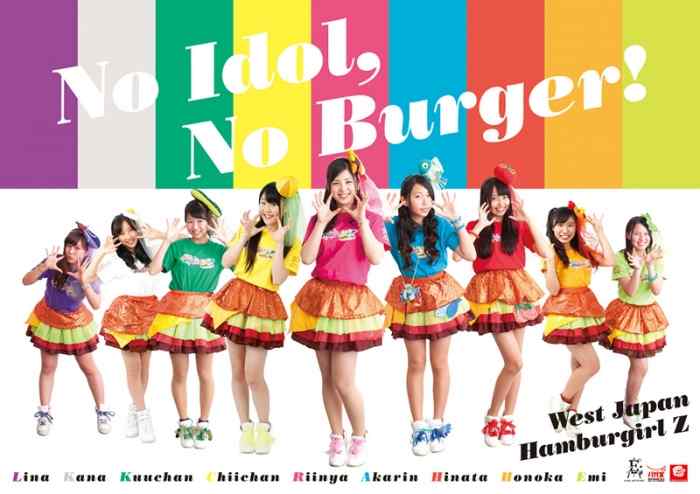

Morning Musume is AKB48’s closest competitor, started in 1997 and is the second highest on Oricon’s music chart, according to Wikipedia. Other idol groups are nearly indistinguishable from normal pop artists, like Perfume who is made up of three members or Momoiro Clover Z who are well known for the Sailor Moon Crystal theme song, or more recently, Babymetal. They don’t have to be in a group either. Kyary Pamyu Pamyu is a solo artist who started as a fashion blogger. Her aim is to make fun of the idol genre altogether (Covington, 2014). Even though Hamburgirl Z group is bordering on hilarious with each member representing an ingredient on a burger (Mami, 2015), perhaps the strangest idol group of all is KBG84 that is made entirely of the elderly (Phro, 2015).

Up Front Promotion is another company that holds auditions for aspiring idol performers, that can be anywhere between 7 years old and 20, although the turn over rate is very high and many of the girls don’t last long. When an AKB48 idol member hits 25 years old they are replaced by a younger member. The recruitment process has a mixture of judges and a voting system, similar to The Voice or American Idol (Covington, 2014).

Jimusho or those who work in agencies have multiple roles like teaching their idols singing, dancing, theatre, and organizing television, commercial and film appearances. The fact that idols are recycled through a big brand name means that children can grow up with them and remain fans for life, allowing them to be drawn to the group out of nostalgia purposes as well (Galbraith & Karlin, 2012). This is brilliantly displayed in 桜の栞 by AKB48, with many comments re-mincing on the idol members earlier years.

The fans themselves have developed a nasty stereotype of being obsessive and even crazy, like the extremes of fandom in the West but possibly more widespread. However, the industry thrives on creating these kinds of fans. In 2011 an event was hosted where fans were able to shake hands with their favorite idols on the condition they bought a CD. With every additional handshake, another copy of a CD needed to be purchased. However, pathological cases of fans are littered over the internet, one being a 24 year old man who sabotaged a hand shaking event by wielding a chain saw. In South Korea and Japan, idols sign a contract that says they must keep their relationships completely secret, perhaps to give the illusion of being innocent and available, so many choose to not date altogether (Airi, 2013). It isn’t just the idols that have the high potential of being treated disrespectfully. Sometimes the company’s marketing ploys are brought to unfair, scam-like heights. “Supporters”, as they like to call themselves, were outraged when tickets for an Arashi concert didn’t even guarantee them a seat, and they had to pay an additional fee for the ticket to be refunded if they didn’t get in (Galbraith & Karlin, 2012).

What does the anime genre of ‘moe’ and idols have in common? Not only did AKB48 start off aiming their songs toward anime fans by dressing up in sailor suits and cat ears (The Eternal Student, 2013), but both have young and cute girls. This is not dismissing the squealing fans for the male idol groups though. Their appeal may be similar to what draws fans to the pop groups in the first place. According to Yaiko Shimizu from Asian Pop Shock, “I think, for some Japanese fans who are attracted to the ‘cuteness’ of male idols, a lot of the appeal has to do with the implied openness and sensitivity that’s presented as being a part of that kind of persona. While a cute idol can still be masculine – think Arashi’s Sho Sakurai – he’s not someone who’s likely to be perceived as threatening. It makes these idols safe, comfortable love objects, particularly since they’re generally considered out of reach.”

Moe has multiple meanings depending on the context (ANNCast, 2013), although psychiatrist Sato defines it as a “quasi-love for a fictional character” (Hornyak, 2014). There are varying opinions on the subject which Galbraith highlights in an interview with Otaku USA on his book The Moe Manifesto,”Affection for fictional characters was a something to be stated, shared, something political. I remember these guys passing out fliers in Akihabara. Half of them were dressed like Haruhi Suzumiya – many of them guys, by the way – and the other half were dressed up in the helmet, dark glasses and face towel that marks the student radical in Japan. They were just sort of playing around, but also saying these radical things. Like, no censorship of manga, regardless of content, or no to the three-dimensional, so-called “real” world.”

Know Your Meme (2010) adds that the moe genre deals with cute characters, while Okada Toshio says the rising of moe can be blamed on men in their 30’s who grew up watching Neon Genesis Evangelion. More than that, they have adopted spending habits similar to young girls who fill their rooms up with all things adorable and innocent. The 80’s was a time where more consumer goods were aimed toward otaku and it is unclear if it coinciding of the idol golden age is related or coincidence. Most fans of moe claim that their consumption of the material is out of a protective instinct, but ‘nurturing’ dating simulator games that involve a relationship with a moe character turning sexual tell a different story (Galbraith, 2009).

There is a lot of cross over of the moe genre and the idol anime genre. ANNCast (2013) like to point to K-On! (2009) for the beginning of anime with a more cutesy-than-usual art style. This show centers on a group of girls who play music as part of their school club, so while K-On! focuses on a group of budding musicians it is not an idol anime. Where did it come from? Funnily enough, the idol genre seems to include anime centered around the music industry, possibly because the idol and entertainment industry are so intertwined. For example, earlier this year Japanese fans got to vote on their favorite Top 16 Idol anime with 80’s hits Super Dimension Fortress Macross and Magical Angel Creamy Mami ranking top of the list (Schley, 2015). However, these relate to individual artists and not a group.

When most Western anime fans think of idol anime more recent series come to mind that include an entire group of idols. These shows are basically soap operas which tend to focus around what it means to be part of that industry. Funnily enough, the sports anime Basquash (2009) had a group of three side characters who were part of an idol group, but it was not the main part of the story. The series’ focused solely on a large group of idols seemed to have come later. AKB0048 is a 2012 series based in the future about – who would have thought? – the monster idol group of AKB48, including their songs. According to The Nihon Review, as ridiculous as the sci-fi premise is it is played “straight enough that it somehow works”. Beyond the craziness of AKB0048, Wake Up, Girls! shows the darker side of the idol industry and has been praised for its characterization (Kazar, 2014). It is receiving a second season.

Love Live! School Idol Project (2013) and The Idolm@ster are incredibly popular, so much so that the Love Live film received a film screening in Australia this year. Love Live! is available on legal streaming sites and introduces the premise in a way that eases the unassuming viewer into the world of idols. The main character knows very little about the topic until she discovers a school that teaches on how to be one.

Variations on these types of schools do exist. A very expensive, elite school for athletes and artists is Horikoshi Gakuen in Tokyo. Many famous idols have attended this school although they are escorted by bodyguards on campus. The classes are divided into University (‘mainstream curriculum’), sport and art which includes music and idols (Sofiana, 2012). According to Blah! Since I Know blog their entertainment course is called TRAIT, and a new rule from 2010 meant that these students must be accompanied everywhere by a teacher even if they already have bodyguards and are not allowed to communicate with other students. There are also strict rules on uniform, personal presentation and dating. Thankfully, there are plenty of other art schools in Japan that are not as prestigious as that one (Sofiana, 2012).

Idolm@ster takes time to investigate the character’s conflicts and challenges with their stage personality and real self, something which is very important to building characters (Smit, 2015). In this way the characters in an idol anime are shown with more respect and care than the blatant walking advertisements of real life idols. Songs aside, it is fortunate that the score for these series are quite high although the artwork and animation can leave a lot to be desired. In Love Live! the use of 3D animation is considered distracting (Creamer, 2015). Wake Up, Girls! has the most mature visual aesthetic as far as coloring and character design work goes. In the first episode writing keep to the point and the main character’s energy helps add an upbeat quality to scenes. Perhaps because of its length Love Live‘s direction and writing is strong and could contribute to the series success compared to idol series that came before it (Creamer, 2015).

The idol phenomenon in Japan has became such a major part of Japanese culture that it infiltrates and feeds off every aspect of the entertainment industry, similar to how Agent Smiths can make themselves appear at any point in the Matrix. It isn’t exactly surprising that given their heightened popularity in the past couple of years that more anime that center around idol groups have been coming out. Anime therefore is added into the continuous, circular stream of media aimed to promote product, although the animated series have an opportunity to showcase the darker and more serious aspects of idol life, which could make them more valuable than a concert depending on one’s reasons for engaging in that material.

Works Cited

(2013). Girl groups: A social phenomenon in Japan. Hope Sings. Retrieved 13th November 2015 from: http://hopesings.net/blog/2013/7/16/tmrmvi1s94pkihumbh7e3yoe5h66vh

(2012). Horikoshi Gakuen, High School of the Famous. Blah! Since I Know. Retrieved 14th November 2015 from: http://blahknow.blogspot.com.au/2012/05/horikoshi-gakuen-high-school-of-famous.html

Airi. (2013). Lets Talk About Japanese Korean Idols and that No Dating Rule. Let’s Throw in Western Idols Too. Retrieved 14th November 2015 from: http://www.mibba.com/Blogs/Read/542518/Lets-Talk-About-Japanese-Korean-Idols-and-that-No-Dating-Rule-Lets-Throw-in-Western-Idols-Too/

ANNCast. (2011). Moe Money, Moe Problems [podcast]. Retrieved November 13th 2015 from: http://www.animenewsnetwork.com/anncast/2011-01-06

Bennett, C. (2012). The mystique of the Japanese male idol. CNN. Retrieved 14th November 2015 from: http://geekout.blogs.cnn.com/2012/05/03/the-mystique-of-the-japanese-male-idol/

Campion, C. (2005). J-Pop’s dream factory. Retrieved 13th November 2015 from: http://www.theguardian.com/music/2005/aug/21/popandrock3

Covington, A. (2014). Unraveling a fantasy: A beginner’s guide to Japanese idol pop. Retrieved 13th November 2015 from: http://www.avclub.com/article/unraveling-fantasy-beginners-guide-japanese-idol-p-206896

Creamer, N. (2015). Review – Love Live! School Idol Project. Sub.Blu-Ray – Season 1 [Premium Edition]. Retrieved 14th November 2015 from: http://www.animenewsnetwork.com/review/love-live-school-idol-project/sub.blu-ray-season-1/.83897

Galbraith, P. W. (2009). Moe: Exploring Virtual Potential in Post-Millennial Japan. Retrieved 13th November 2015 from: http://www.japanesestudies.org.uk/articles/2009/Galbraith.html

Galbraith, P. W. & Karlin, J. G. (2012). Idols and celebrity in Japanese media culture. Retrieved 13th November 2015 from: https://masterofants.files.wordpress.com/2013/09/idols-book.pdf

Hornyak, T. (2014). Japan’s ‘Moe’ obsession: the purest form of love, or creepy fetishization of young girls? The Japan Times. Retrieved 13th November 2015 from: http://www.japantimes.co.jp/culture/2014/07/26/books/book-reviews/japans-moe-obsession-purest-form-love-creepy-fetishization-young-girls/#.VkWYmnYrLcd

Kazar, K. (2014). Wake Up, Girls!: The Ani-TAY Review. Retrieved 13th November 2015 from: http://tay.kinja.com/wake-up-girls-the-ani-tay-review-1556487586

Know Your Meme. (2010). Moe. Retrieved 13th November 2015 from: http://knowyourmeme.com/memes/moe

Mami. (2015). Meet The World’s Only Hamburger Idol Group: Hamburgirl Z. Retrieved 13th November 2015 from: http://www.tofugu.com/2015/10/06/interview-with-hamburgirl-z-japan-hamburger-idol-group/

Phro, P. (2015). KBG84, Japan’s oldest idol group, release their first major label single. Japan Today. Retrieved 13th November 2015 from: http://www.japantoday.com/category/entertainment/view/kbg84-japans-oldest-idol-group-release-their-first-major-label-single

Schley, M. (2014). The Moe Manifesto: Patrick Galbraith Interview (Part One): The author behind the new book on moe. Otaku USA. Retrieved 13th November 2015 from: http://www.otakuusamagazine.com/Anime/News1/The-Moe-Manifesto-Patrick-Galbraith-Interview-Part-5772.aspx

Schley, M. (2015). Japanese Fans Rank Top 16 Idol Anime: What? No Chance Pop Session?! Otaku USA. Retrieved 13th November 2015 from: http://www.otakuusamagazine.com/LatestNews/News1/Japanese-Fans-Rank-Top-16-Idol-Anime-6175.aspx

Smit, A. (2015). The idolm@ster Anime Wants You to Believe in Idols, and Here’s Why You Should. Retrieved 13th November 2015 from: http://www.themarysue.com/the-idolmster-anime-wants-you-to-believe-in-idols-and-heres-why-you-should/

Sofiana, N. (2012). Horikoshi Gakuen is the most elite high school in Japan. Retrieved 14th November 2015 from: http://natsujapaneselovers.blogspot.com.au/2012/04/horikoshi-gakuen-is-most-elite-high.html

The Eternal Student. (2013). The Social Phenomenon that is AKB48. Retrieved 13th November 2015 from: http://lameibergen.tumblr.com/post/43449279092/the-social-phenomenon-that-is-akb48

What do you think? Leave a comment.

The only Idol anime I’ve watched completely was Wake Up Girls, but by god did I love it. One of my favorite animes from last year, and rewatching it is making me consider adding it to my all time favorites. I’ve watched a bit of AKB0048 but never finished.

For anyone interested in idol animes: definitely watch AKB0048. It’s especially good for getting guys interested in the genre. I had a few male friend who were completely against idols in the first place, but grew to love them through AKB0048.

It’s practically a Gundam show but with cute singing girls doing the fighting xD

The Japanese idol has always been really fascinating to think about (what subcultures is this group fusing together, what social phenomenom is behind it).

In my mind, J-Pop is the ultimate “immersion required” genre/category of music. While I am not really interested in idol pop,

This is true. Understanding J-Pop requires you to immerse in stuff like Persona 3 & 4, JRPGs, the Yakuza games and slice of life anime.

This was a hell of an article.

Honestly for me, the best idol remains “Kouyama Mitsuki”.

For an article with such a bountious list of references, it would really help if parts of it weren’t overburdened with frequent reference tobsources for facts that don’t need to be cited. Statements like ‘Jpop is a broad term that refers to Japanese pop music, or even popular Japanese music’, for instance, come from a bank of shared knowledge, aren’t governed by one source and don’t need direction as to where one can find further clarification for the assertion.

Not sure if articles can be revised after publication, but editing out these unnecessary citations would make for a much smoother read, and would give the article the academic edge it deserves (for its so-well-researched nature) rather than the trying-so-hard-to-be-academic feeling it gives off with its over-abundance of references in parentheses.

Someone did give me this feedback when it was pending for publication, and I tried changing the referencing style to something different, but it didn’t quite work, so I wasn’t sure what to do. If you can think of something else (maybe just remove some of them?) I’d like to know. I struggle with removing in text citations because my University is very strict about referencing. Thanks!

My university is strict about not referencing too much ><

Understanding that anything that isn't common knowledge or from personal experience ought to be cited, the main issue seems to be that 'Galbraith & Karlin' crops up at least once – sometimes thrice – per paragraph. It makes the opening and first part of the article read mostly like a re-representation of their work, and the lack of page numbers makes trying to use those citations a nightmare; if page numbers were being used, multiple references to G&K in one paragraph, if needed, could be covered by the second instance being merely '(page number)'.

I'm sure there are however many other sources that could cover a number of things they mention, including the sources they cite for the information this article has used without full citation to their origin. Regarding the fact that 'half of Japanese households had a television in the 1960s', for instance, Galbraith & Karlin reference 'Yoshimi 2003, 37'. Not only that, but the statistic is that /more that half/ of households had a television /by 1960/. The link between the first idol agency and the ownership of televisions is also something I couldn't immediately get – were the first idols immediately seen/needed on television? The existence of stand-up comics, for instance, pre-dates their first emergence onto the little screen. G & K seem to argue that it took another decade for Japanese celebrity culture to infect – and be infected by – television in the way it was.

Since the cited text is an electronic version of a G & K's published book, the bibliography's reference should also include information about the work's publication.

'Calbraith and Karlin' is also cited once. Not sure who that is.

You make good points. I’ve just had one of the admins remove a number of the in text citations to make it easier to read. The “Calbraith and Karlin” one is referencing a website.

The reference list itself isn’t as “by the book” with APA as it could be, but at least the basic elements are there. The Artifice isn’t overly strict on referencing because every author uses a different system so I can get away with it.

I never realized how far back “idol” culture went in Japan. It’s incredible how long a brand can keep going just by replacing its members regularly. Despite all the obsessive fandom that goes on, I wonder how often they risk over-saturation with all the advertising that goes on.

Excellent article.

I only have three (non-constructive) things to say about Idols and Idol anime:

1. No.

2. GTFO.

3. You are guaranteed to have zero-development of anything in order to not incur the wrath of the crazy Otaku.

Saw both 0048 and Perfect Blue, both of which represent the opposite sides of the idol coin, and tell stories differently, one from a master who skillfully combines sci-fi/fantasy with idols, the other a master of suspense and macabre and cynicism. One sees the evolution of would-be young entertainers, from all walks of life, to be put into a long-running battle to win hearts and minds of people and to defend their right to perform, figuratively and literally; the other sees how a former idol tries to change her image by breaking away (it’s called “graduation”) and trying something uncommon by becoming an actress in a third-rate production, but with dire consequences both to her and to people around her.

Anyone remember Idol Defense Force Hummingbird and Idol Project? Yep, the 90s had some of this too.

My descent into idol hell… I got around to Love Live only after being unable to escape it. I thought it was fine, but I didn’t really feel the need to keep going. Cute girls doing cute things, as a whole, was sort of something that I didn’t really get. It was boring. After going through some pretty intense stress in my life, though, I revisited Love Live, just because I wanted something that to relax to. It worked. It worked incredibly well. I’ve been unable to escape since.

Watching Idol shows, for me, is like watching any other Iyashikei show. It makes me feel happy.

It’s easy to de-stress and enjoy the small things when you are watching a group of girls do their best to achieve a simple but admirable goal and to just make people happy. I don’t think it is an overstatement to say that Idol anime played a part in getting my life back on track. And I will always love them for that.

My personal favorite is Wake Up, Girls!, just because of how real it feels, in contrast to other Idol shows. The one thing lacking from most other Idol shows, in my opinion, is that, sometimes, they seem soo idealized, that its hard to imagine them as real people. And therefore a little harder to get invested in them. Wake Up, Girls! had a lot more of an impact on me, because it addressed that issue. It put the girls through much tougher trials, but showed them overcoming them and coming out better for it. It is still heartwarming and triumphant, but not fake, or sugarcoated.

What’s really intriguing has been the games (usually the ones we don’t get in the US). Most of the anime I’ve seen focused on idol groups could be saying a lot more about the music world, but instead come down to believe in yourself and moe fanservice. Wake-Up Girls was a major disappointment in that category.

I agree about Wake Up, Girls! I never got past the 3rd or so episode.

I certainly appreciate the detail and at-length coverage of this article.

Thank you. 🙂

I appreciate the extensive amount of research put into this very interesting article but as a complete novice in this subject I fail to see the significance of these musical groups. I guess more to the point it would be beneficial to explain how these groups came to have such cultural influence and commercial success. How have they endured and become a staple of Japanese and Korean culture as opposed to fading away like so many other pop fads?

I guess that’s the same question of why particular product sells over others. It is a difficult question to answer as it isn’t easy to predict the market/fan reaction. Obviously the combination of cute girls/boys and catchy, upbeat music seems to appeal to a large number of people in Asia.

Idol anime make people happy.

Aikatsu will always be my favorite idol anime. Locodol was pretty fun too, but those 2 are all I’ve seen.

Good post. As for me watching idol anime, it’s more for an nice, easy experience with very cute characters and good music for the most part.

I’ve also sorta found myself sucked into the world of idol anime through Love Live. Although it’s not that I’ve ever thought them “beneath me” – as someone who once sung the school anthem from K-On! in his cousin’s wedding limo, I don’t think I’m in any position to be casting stones.

I have lived in japan for a few years now and i have been exposed to most strains of japanese pop. take my opinion or leave it, but i believe that perfume is the only j-pop worth listening to, basically without qualification. unlike AKB and mostly every other idol group, the perfume girls’ ‘personas’ are pretty much secondary; their performances (and indeed, their auto-tuned vocals) are all deliberately as robotic as possible.

But musically, perfume is electro/disco pop on a VERY sophisticated scale.

Western audiences have a weird knee-jerk reaction to the cutesy robo-voices of perfume, but even if you were to ignore the vocals entirely (even though the lyrics are actually not bad, in perfume’s case) you would still be left with solid electro that i’m would find an audience even in western markets.

The production is fkn phenomenal and some of their latest tunes have even (non-surprisingly) started borrowing elements from dubstep and drum & bass. of course it’s all thanks to producer yasutaka, but his other projects (kary and capsule) aren’t nearly as well-executed as perfume.

Perfume is easy to get into.

I love One Room Disco, Glitter and Secret Secret. And that’s particularly due to Yasutaka Nakata’s wonderful Electro House productions.

I appreciate how indepth this analysis is! I find it fascinating that there are different words to define sexy-cute, classy-cute and trendy-cute. How does this cultural trend link in to the rise of Hatsune Miku and vocaloids?

I can’t believe I forgot vocaloid! http://www.digitaljournal.com/article/315756

It began in 2007 which is close date wise to the beginning of AKB48.

Macross definitely puts up familiar idols in the form of Lynn Minmay and Ranka Lee, where they go from nobodies to winning contests, rising in popularity, and basically objectified and commercialized extremely fast. I guess the major difference to the bevy of idol anime now is that they’re all solo acts and not part of huge groups, except for Fire Bomber who are rockers and not exactly idols.

A lot of the idol fanbase are corporate slaves, it’s true, they are oblivious to the suffering their favorite idol may be going through, don’t care, and in some cases defend it.

Considering that idol groups really became a Japanese cultural phenomenon in the 1970s, I’m actually surprised that it took the trend so long to be reflected in anime. I reviewed the anime Locodol for several months ago, and in that review I gave a brief historical overview of the development of idol groups in the Japanese music industry. It seems that anime finally caught up soon after idols themselves became animated; for instance, the Vocaloids. The development of these new virtual idols–who literally belong to anyone who uses them–is in complete contrast to the environment that existed early in the Japanese idol phenomenon, when handlers and record companies sought to increase idols’ popularity by surrounding them in secrecy and even fabricated bios. Again, I’m just surprised that anime is so late to this party.

There have been idol characters in anime for a long time, but it has only become incredibly popular in the past few years to have anime based solely around idol groups.

Am I xenophobic for being fucking creeped out by how these girls are manipulated and essentially turned into living dolls for the public’s amusement?

Are they any more produced and packaged then Britney Spears or New Kids on the Block? It’s part of the music business for better or worse.

Yet another brilliant article, Jordan! I haven’t personally watched any idol-based series before, but I have been noticing the growing trend of idol activity and it being more and more picked up by the media in news, anime, and gaming these days.

The term, “idol” for them is perfect as it illustrates the positive and negative within their line of work. The positive being that they get to become the center of attention and become well respected and revered as a role model which people should follow. However, there is also the negative in which it is unknown whether this figure being shown is their true self or a false representation brought about by the media attempting to craft their own perfect beings.

Thank you, and good point about the name ‘idol’. 🙂

I’ve always wanted to see an anime that deconstructs the idol phenomenon.

All I know of contemporary Japanese music is either classical (Toru Takemitsu, Toshio Hosokawa [who I briefly got to meet]) or film (Ryuichi Sakamoto, Joe Hisaishi).

This whole idol thing is just one aspect of j-pop, it seems that pop music in japan, like anywhere else on earth, is filled with mostly just harmless love songs. (and some japanese alternative rock bands are pretty chill.

AKB0048 was my first known foray into idol anime; Macross Frontier (followed closely by the original Macross SDF) were my true “firsts”, though those seem much, much closer to normal pop artists that modern-day idols. I liked AKB0048 a lot, but I can’t tell if it’s just because of how it ran against the grain or because it felt more sci-fi than slice of life.

Arashi is part of Johnny’s Entertainment, whose head is the Japanese Lou Pearlman and was accused of pedophilia many many times.

For the first time, i actually boycotted the Japanese release of Howl’s Moving Castle because it has a Johnny’s member voicing Howl. It was great that Christian Bale voiced Howl in the US release instead.

It’s hard to recommend any of the Japanese boy bands as something to actually listen to for pleasure, rather than just ironically. I say this as someone who considers Kouhaku one of the highlights of their year, too.

and shrieking idol girl groups are better because they cater to your asian school girl pedo feitish amirite.

but he didn’t do anything wrong, the head of the company did. kinda dumb to boycott over that though..

I still have Utada Hikaru’s Ultra Blue unopened, which I bought in Japan many years back which I really must get around to listening to. I really liked her theme song for one of the Neon Genesis Evangelion Rebuild movies too.

The Japanese have created this extraordinary scene for their celebrities, particularly for their musical celebrities. I have always found their fascination with this intense worship scene for pop idols, and as I began to understand the difference between the fan experience compared to the United States, I also became more interested in the celebrity experience. Jpop idols have a lot of expectations to live up to, including, but are not limited to things such as making it seem as though they do not indulge in personal romantic relationships; because they are supposed to maintain the image of availability (so that the fans can imagine and fantasize about them dating the idols themselves) – which sounds completely absurd, even with our insanely obsessive paparazzi culture here in the U.S. It’s incredibly interesting the differences between the Japanese and U.S. standards for celebrities. This was an excellent article!

Thank you! I also find the approach to their celebrities very interesting. It obviously works well, so I’d be interested to see what would happen if something similar was done in a Western culture.

Japan has a lot of interesting and exciting culture. Jpop is the opposite of all that.

Could you expand on what you mean?

AKB0048 is an odd one, even for an idol anime. At times, it both celebrates and is critical of the idol industry, especially with its usage of the AKB0048 successor drama that drives so many of these young girls to both strive to be their best, but also to do so by becoming in spirit the original AKB4008 members.

There are a lot of different ways to go about with Idols. Love Live and Idolmaster being two series that you mentioned I have seen. There is also IdolMaster Cinderella Girls. Each ones has their own ways of showing off what idols are like. Love Live, despite being a little humorous at times, still has drama, but more of the idea of trying to become one. Idolmaster is the more real life, sort of thing. Cinderella Girls, despite my dislike for it, was more all drama and showed the more conflicting points in an idol life. Each have something to promote, Love Live has their VAs, Idolmaster has their games. But they can still say something about the idea of ideas as a whole, and in some ways become just as popular as real ones.

It seems like some of your facts about idols are just wrong

“Up Front Promotion is another company that holds auditions for aspiring idol performers…”

-Up Front is the holding company for Hello Project, the company that Morning Musume is a part of. While they do have their own idols, it’s a complicated relationship where artists in Hello Project are also in Up Front.

“When an AKB48 idol member hits 25 years old they are replaced by a younger member. The recruitment process has a mixture of judges and a voting system, similar to The Voice or American Idol (Covington, 2014).”

-AKB members aren’t forced to graduate when they hit 25 – current AKB idol Kojima Haruna is 28 and still in the group. Members graduate when they want to, or are forced to when they are caught in “scandals” (which is basically dating). In fact writing about the scandals and expectations of purity may be a good direction to explore, since it’s such an unspoken standard when talking about idols.

“However, pathological cases of fans are littered over the internet, one being a 24 year old man who sabotaged a hand shaking event by wielding a chain saw.”

-If you read the article, a “50cm saw” is not a chain saw – it was a foldable handsaw. Not any better, but hardly some grotesque horror-movie chainsaw. The man who attacked them was also not a fan; further reading on the topic will reveal that it was a mentally unhealthy person who literally said he wanted to attack someone, and the handshake event was convenient.

As an idol fan myself these things bothered me about the article, as they perpetuate stereotypes and are such blanket statements. I hope the article will be revised with the correct facts. I would also hesitate to call Babymetal just another idol group given their recent appearance on the Late Show, but to each their own.

“I would also hesitate to call Babymetal just another idol group given their recent appearance on the Late Show, but to each their own.”

but they are. the only thing that makes them different is that they’re layering their voices over a heavy metal track, but really they’re just another sub unit of typical idol group that’s trying to be edgy.

you also cannot deny that female idols aren’t meant to be a certain age. kojima is anomaly because being a female idol over the age of 30 is seen as embarrassing in japan.

Some very interesting points… Great read!

The article does remind one that the entertainment industry is much more controlled in Japan than in, for example, the United States. It is very reminiscent of the Studio System in the United States from the 1930s to the 1960s.

The article’s discussion of idol anime in relation to the rest of the industry is super compelling! With the globalization of the idol industry it gets harder and harder for fans/consumers to appreciate the complexity of the systems responsible for producing this kind of celebrity. With how tightly regulated and censored idol discourse often is by companies, exposure to the negative sides of the industry can really only be explored in depth through fiction. In that sense, I agree that idol fiction, whether it’s anime or dramas, offers a unique opportunity for critical engagement with the idol industry.

However, having just recently watched “I Will Be Your Bloom”, I wonder if live-action narratives starring idols are equally critical. Anime and other media which don’t directly map a recognizable person to their characters seem more free to explore and challenge industry norms and struggles than idol actors who are always superceded by their idol persona.

Regardless, I think these kinds of narratives are valuable for giving new fans who may not know much about idol culture context that encourages a more ethical and humanized perspective for consuming idol media.