The Shawshank Redemption: A Retrospective

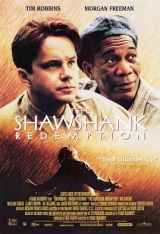

Twenty years ago (or for you anal retentive folks, twenty years, two months, and eight days ago), Frank Darabont’s prison drama The Shawshank Redemption was released. As with most releases, some didn’t care for it while others did. Although the general consensus amongst film critics ended up being in the film’s favor, it failed to attract the public’s attention, and was deemed a box-office flop. Come award season, the Academy teased the film, but ultimately left it empty handed. Out of its seven nominations, Shawshank received a resounding zero, losing all the major awards (Best Picture, Best Adapted Screenplay, and Best Actor) to its “competitor,” Forrest Gump. On paper, this film seems like a fluke; just another movie that received some praise when it came out, but couldn’t manage to stand against the test of time. How wrong one would be to think that.

Since its release, the film has proven to be anything but forgettable. It’s listed as #1 on IMDb’s Top 250 Films List (beating such films as The Godfather, Citizen Kane, and yes, Forrest Gump), #4 on Empire’s 500 Greatest Films List (also beating Forrest Gump), and #72 on the 10th Anniversary of AFI’s 100 Years…100 Movies List (you get the idea). Roger Ebert went on to declare it a Great Movie, and Tim Robbins is fond of telling the story of how Nelson Mandela personally told him that he adored the picture. Though it may seem like it, this is not a case of a film gaining a cult following. This is a movie that re-enacted its heroes’ escape from imprisonment and came out clean on the other side. Of course people are free to make what they will of the movie, but no one can claim that it hasn’t managed to carve out a rather noticeable place for itself in the pantheon of cinematic greats. Thus we reach the obvious question; how did the cinematic equivalent of the neglected girl standing alone in the corner of the gym while the prom rages on become the belle of the ball?

Regarding the film’s behind-the-scenes action, I defer completely to Margaret Heidenry, a writer for Vanity Fair, who has compiled a thorough history of the film’s production and release that provides information (or at least detailed speculation) as to why the film failed to gain an audience when it opened. The marketing was blamed, the budget was blamed, even the movie’s title was blamed (according to Morgan Freeman, it was difficult to say it smoothly, so it stands to reason that no one would want to watch a movie whose title they can’t even pronounce). The issues concerning the film’s cosmetics are certainly worth noting, but they aren’t what ultimately sunk the film. If there was any one problem that caused Shawshank to be dismissed, it was that that it failed to provide audiences with the blazing cinematic bravado that most 90s films were adopting, and instead opted for a quieter, more emotional story that didn’t mind embracing its humility.

In 1994, the cinematic world was divided between two films: Robert Zemeckis’ Forrest Gump and Quentin Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction. The former was built all around sentimentality and nostalgia which is a great, if easy, way of hooking in audiences. The latter gave birth to the “indie” genre by featuring a cast of ingenious characters, a slick soundtrack, a uniquely fragmented storyline, and a magnificently dark sense of humor. In a grander sense, these films functioned as microcosms of what may be called the classic and the innovative. While Forrest Gump told its story through a series of flashbacks that were filled with moments of sadness that balanced out with moments of levity, Pulp Fiction took glee in subverting your expectations, making you laugh one moment, cringe the next, then making you laugh again. Pulp Fiction‘s novelty immediately guaranteed it a place in pop culture history (go up to anyone and ask them what they’d call a Quarter-Pounder with Cheese in Paris and they’ll tell you, regardless of whether they’ve actually been there), but Forrest Gump still had a lot going for it in spite of its romantic sentiments. The film starred Tom Hanks, one of the 90s darlings who was hot off his 1993 Best Actor win for Philadelphia, it was directed by one of Steven Spielberg’s proteges, and it did have a fine emotional core that ranged between the heartwarming, the tragic, and the humorous. The point here is that while Forrest Gump wasn’t anywhere as original or exciting as Tarantino’s picture, the story was still told using the energy and intensity that was so prevalent in 90s films. It was like your cool grandpa who, as old as he is, still manages to kick your butt at Mortal Kombat from time to time, and not down at the arcade, but at home on your Xbox One.

Shawshank, on the other hand, was a pure classic. It had little known actors (at least for the time), the filmmaking itself wasn’t very exciting, it had a linear storyline, and though the film had an emotional core, the dominant emotions were melancholy and hope. Moreover, the film was almost entirely masculine, featuring only a handful of actresses (mostly as extras), which doesn’t do a whole lot of good in hooking in the female crowd. In essence, the film didn’t have enough new stuff in it to call itself hip, and it was lightyears away from being a purely novel experience. It was just a story about simple people caught in extraordinarily dismal circumstances, and how they managed to find a way to cope with their problems. People in the early 90s just didn’t want to see that; it was literally too ordinary to enjoy.

Yet when 1997 rolled around and the film started airing on TV, people liked it, and they liked it for all the reasons that the film had previously been ignored for. The brevity of the story was something that people could enjoy and gravitate towards, and because of its classic tone, it had a timeless quality to it. But as with the question of why Shawshank initially failed, it’d be too easy to say that cable re-runs of the film were the sole reason it bounced back. While there’s no definitive answer, I’d like to think that the reason the film was not only revived, but has managed to be passed down through the years was that its message of hope and grace was able to calm an audience of hot-blooded action junkies who had become too used to high-octane thrill-o-ramas.

In order to provide audiences with an engrossing experience, storytellers must give them sympathetic characters and a compelling story. Back in 1994, there weren’t a lot of filmmakers doing that. In fact, most of the popular movies released that year supplanted emotional substance with pyrotechnics and zany comedy; movies like Dumb and Dumber, Ace Ventura: Pet Detective, Speed, The Crow, The Mask, True Lies, Natural Born Killers, Clear and Present Danger, and Leon the Professional. Granted some of those movies were good, but they did not provide a cinematic environment in which a movie like Shawshank could be appreciated. But by 1997, audiences were starting to get movies that revolved around genuine human drama and were praised more for their narrative than for their superficial qualities; movies like Amistad, Chasing Amy, As Good as it Gets, Gattaca, Contact, Life is Beautiful, Titanic, Boogie Nights, and Good Will Hunting. People were calming down and becoming more tolerant of movies that didn’t deal in bullets, but in feelings and ideas.

Shawshank‘s triumph, then, was that it nailed the narrative bulls-eye, it just took people a while to realize it. Not only did the story revolve around a man who is sent to prison for a crime he didn’t commit (which to this day is great dramatic material), but the main characters were so vivid and emotionally complex that they’ve managed to become immortal cinematic figures. Any good story can teach people about the honorable things in life, and it’s hard to think of any better teachers than Andy and Red, the film’s central protagonists (this is spoiler country, so if you’d like to see the film, read at your own discretion).

It may be a jump to call Andy Dufresne the unluckiest man in cinematic history, but he certainly comes close (at least top ten). He’s accused of having murdered his wife and her lover, and after providing a brutally honest testimony in which he admits his mistakes while proclaiming his innocence, he is found guilty and ordered to serve two life sentences at Shawshank Prison. In case any audience member remains skeptical of Andy’s innocence, a character in the film later tells him that he met a prisoner who claimed responsibility for the murder of his wife, and gleefully declared that he got away with it because the police had pinned it on Andy. Time and again he argues his innocence, but is always cast down by the powers that be. Because he will not allow himself to be condemned for something he didn’t do, Andy eventually hatches a plan to escape from the prison and bring vengeance upon the malicious warden and captain of the guards, a plan which eventually comes to fruition. As an individual, Andy is not only a warning against those who would take advantage of people at their weakest (since he proves that given enough time, justice will be served), but also the kind of person that the Viennese psychiatrist, Dr. Viktor Frankl, lauds in his book, Man’s Search for Meaning.

A victim of the Holocaust, Frankl found that prisoners who focused on the meaningful things in their lives (e.g. their wives, children, parents, friends) were more likely to survive in the death camps than prisoners who resigned themselves and allowed the Nazis to become the sole arbiters of their existence. Andy is undoubtedly an example of the former; while he does endure the most inhumane treatment at the hands of prisoners and guards alike, he never allows himself to fall into despair. Instead, he does productive things with his life. Being a banker, he gives the guards financial advice, builds a library with funds provided by the state senate, plays music for the prisoners, and even becomes a teacher. Towards the beginning of the film, Red warns his fellow prisoners that when, “they send you here for life, that’s exactly what they take. The part that counts anyway.”

Though he doesn’t set out to do so, Andy basically proves him wrong. By finding meaningful things to do in a relatively meaningless environment, he shows that we are only as worthless as we let ourselves be. There are many callous, brittle people who wallow in their pride and self-righteousness, but they do not own the truth and they are not allowed to decide the value of a person’s life. Andy was imprisoned for something he didn’t do, and instead of letting himself die, or worse, become the kind of person that deserves to go to prison, he found a way to make his life matter, both for himself and others. In relation to us, Andy shows that it does no one, least of all yourself, any good to wallow in self-pity and worry, and the best way to prove the wicked wrong is to cultivate goodness. As the Jewish proverb goes, “living well is the greatest vengeance.”

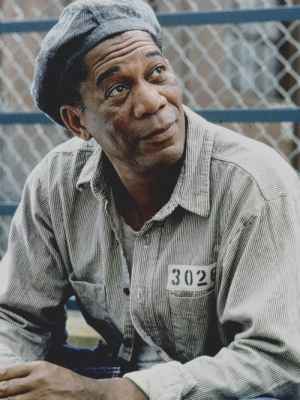

Then there’s Red. The most important difference between him and Andy is that he is guilty of murder, and more than that, he’s the only one who admits to what he did (the other inmates have a running joke that they’re all innocent; Red is the only one who doesn’t partake). He’s a good humored soul, but he’s also very tired, and while he can still see the valuable things in the world, he has a tough time finding any measure of worth in himself. What’s most interesting about him, however, is the effect that Andy has on him. Obviously Andy teaches Red how to hope, and it’s beautiful to watch Red learn how to love life again. But more importantly, Andy provides a portrait of true innocence that causes Red to accept the consequences of what he’s done.

Watch those scenes with Red talking to the parole board again and you will see just how much he changes over the course of the movie. During the first meeting, when asked if he thinks he’s been rehabilitated, Red says, “Oh yes sir, absolutely sir. I’m no danger to society anymore,” with a pair of big puppy dog eyes. During the second meeting, he answers the same way, but this time with less theatrics. And when he’s asked a third time, after having served more than forty years in prison, he finally tells the truth. He says that he doesn’t know what rehabilitation means because to him it’s, “just a bullshit word.” He regrets what he’s done, and he wishes beyond all hope that he could go back and talk himself out of the crime he committed. But he can’t. He’s just an old man who is done begging for forgiveness.

It’s vital to emphasize that Red isn’t saying this because he doesn’t care what people think of him. He’s saying this because for the first time, he realizes that forgiveness can’t be bought, bartered, or argued for. Forgiveness can only be granted through the grace of those who’ve been wronged. The greatest lesson that Red teaches the audience is that in the presence of true innocence, one cannot help but feel humbled and a need to be honest. When we’re confronted with the fact that we’ve done something wrong, there is always the temptation to either lie about it, say it isn’t as bad as it is, or promise that we’ll never do it again (Red never does the first two, but he does do the third). But after enough time and introspection, the truth will come out, and when it happens all any decent person can do is accept it. It may sound crude to call a murderer heroic for owning up to what he did, but within the context of this story, there is something admirable about Red’s eventual understanding that forgiveness is bestowed, not distributed, and in that serene act of self-realization, he becomes the redeemed.

As remarkable as both these characters are on their own, it’s when they’re together that they shine the most and provide us with images of extraordinary moral fortitude. As mentioned before, Andy has a profound effect on Red by teaching him to hope and find meaning in life, and in a roundabout way, he teaches Red to be honest. But this doesn’t mean that Andy doesn’t learn anything from Red. Though he’s hopeful of the future, Andy does find himself in moments of doubt. At one point in the movie, he even wonders if he isn’t somehow indirectly responsible for his wife’s murder. What Red provides Andy in this moment is just as important as the hope that Andy provides Red; it’s reassurance and an honest assessment of the situation. Red tells Andy that it may very well be true that he didn’t fulfill the duties of a husband, but that didn’t give his wife the right to be unfaithful, and it certainly didn’t mean that he pulled the trigger. When moments of hope pass, they are often replaced by undeserved feelings of sorrow and self-loathing, and while Red can’t keep Andy from feeling the way he does, he can at least numb those feelings a bit and provide him with an objective perspective on things. He also warns Andy about the dangers of having too much hope, and how it can end up crippling a man who believes in things that can’t or won’t happen, which ensures that Andy focuses on the tangible methods for dealing with life’s problems rather than fooling himself into thinking that his problems will just disappear.

In the end, it’d be too poetic to claim that these two guys are just halves of a whole, but their friendship is wonderful to examine precisely because of its reciprocal nature. Though I’m not a big fan of the show, I can’t help but think of Modern Family when looking at these two; if Andy is the Dreamer who believes in hope and inspires Red to reach for something that transcends himself and the prison they’re in, Red is the Realist who provides Andy a firm foundation built on experience and cunning that helped his friend survive in Shawshank. There’s no evidence to back up this claim, but if there is any one thing that I’d attribute the film’s belated success to, it’d be that viewers found a way to be inspired by the pair. If someone was going through a problem that wasn’t of their doing, it’s reasonable to assume that they admired Andy’s fearless pursuit of meaning in a place that didn’t nurture it, and how through his wit and patience, managed to find a way out of prison. Conversely, if someone was going through a problem that they had created, chances are they took comfort in Red’s graceful attitude toward himself, his eventual acceptance of what he did and the wisdom that came in knowing that forgiveness is up to other people to decide.

The Shawshank Redemption lends credence to Shakespeare’s claim that, “brevity is the soul of wit,” and its legacy transcends the fact that it went from being discarded to beloved. It’s that at the heart of the story, there is something that we can all aspire to. There’s no gunfights or car-chases, no epic cinematography, no razor-sharp dialogue, no wacky pratfalls, no schmaltzy romance (although there are probably those who would argue against this point). There’s just a couple of men facing the fact that we are all fashioned from the crooked timber of humanity, and realizing that all anyone can do about it is smile, own up to it, and work towards finding something meaningful in life. What’s more lovely than that?

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Fantastic work, August. This is my favorite article that you have written, especially because of the extensive context that you were nice enough to include. Both powerful and haunting, this movie definitely needs to be near the top of anyone’s list of greatest films. Kudos, man! Great job.

Thanks dude, I really appreciate your kind words.

Certainly not the best movie on IMDB, it was a little boring in my opinion!

Which bits in particular?

I’m curious to know what parts you found boring?

I’ve seen it 20 times and each times it gets better. There is no way that it is overrated. It is a major film masterpiece.

I’m with you. Along with movies like Taxi Driver and 12 Years a Slave, Shawshank is really one of those movies that doesn’t lose it’s quality with each viewing and offers something new. Thanks for the comments.

Shawshank is unique in the genre and unlocked a new potential for moviemakers to break the inherent confines of a prison picture.

That’s true, and I’m glad you brought it up. Up until Shawshank, it seemed that prison films were just tough guy movies where the inmates eventually rioted against the guards or it was an “inside” look at the rugged men of the prison system (I’m thinking mostly of Brute Force and The Last Castle). Shawshank offered a quainter look at this kind of movie that dealt more with survival and hope than machismo. Thanks for the comment.

Most overrated film in the history of movies. It’s a great movie but not #1 on Imdb worthy.

I don’t know if I’d call it overrated, but citing it’s place as #1 on IMDb was only evidence of popular approval, not an argument for the film’s quality. It’d be the same as if someone said that Titanic is the best movie of all time because it won 11 Oscars. The awards certainly indicate that someone liked it, but that doesn’t mean that everyone has to like it. Just wanted to make sure that you didn’t think I was prodding people into liking the film. Thanks for the comment.

Amazing movie, one of the very best. Impeccable message and story telling. A masterpiece of film making in every way.

I’m with you. Thanks for the comment.

one of the best films ever!

I agree. Thanks for the comment.

Deliberately paced, finely layered yet simple in the human instincts of survival and friendship. A beautifully done film.

Right there with you. Thanks for the comment.

The thing is this film is similar to Forrest Gump in that it is narrarated by someone and it takes place over 30 years. There are also historical events that are mentioned in both films. The difference was that Gump opened like gangbusters and was packed weeks into its run while Shawshank did not. It needed to be left in theaters and build on word of mouth and then it would’ve played a year. Columbia, a big studio, wasn’t interested, which is a shame. Seeing this film again recently I couldn’t stop watching because you see what prison life is like and how it operates and takes lives from people like Brooks and Red, who become institutionalized. It is sad when films can’t seem to build word of mouth and even in today’s climate, they don’t play many weeks.

That’s a great point that I failed to talk about. Institutionalization is a big theme in the story and serves as the biggest obstacle that Red has to overcome before learning how to live outside the walls of Shawshank. Brooks is a great, and tragic, reminder of people who can’t let go of the past and thus succumb to it. Thanks a lot for your comment.

I’ve seen it 10 times and each one times it shows signs of improvement.

Thanks for the comment Dinah, and I agree that it’s certainly the kind of film that has aged well.

IMDB has it No.1 film of all time.

It is certainly not.

It’s all about opinions. I’m sure Shawshank is not the best film ever made but it is still my favourite movie of all time. Quite different things of course.

I’m not a big fan of ranking movies either; it’s always seemed better to just say that I thoroughly enjoy one over another and even then, I may change my mind about any given movie. IMDb is an aggregate so it by no means should suggest that The Shawshank Redemption is empirically the best movie of all time, it just shows that many people care for it. Thanks for the comment.

It is a significant film artful culmination.

I agree, thanks for the comment.

My favorite movie. Or, all of our favorite movies. The entertainment value is high and our empathy is heightened for Andy and Red. A lot of deserved attention over the years has gone to Freeman, but Robbins carries his part just as well.

That’s true, I remember being confused that Robbins didn’t get nominated for best actor since he felt like the lead, but in time I’ve come to see him as the supporting role. No matter what though, I agree that Robbins deserves a lot more praise than what he’s received since the movie was released.

Turns out that this is one of the best movies EVER made and usually it’s on everyone’s top 10 list.

Thanks for the comment.

Hope is the main theme in this movie. I’d like to add that faith, a virtue similar to hope, is apparent in Red’s character.

That’s true in the long run seeing as how Red doesn’t know whether or not he’ll ever be free, he can only be honest and hope that people will appreciate that honesty. Thanks for the comment.

The execution of the movie was flawless via the edits.

That’s certainly one of the elements that helped it move at a steady pace. Thanks for the comment.

Wow! I didn’t know and would never have guessed that when the movie first came out it did horribly! It’s one of my favorites and I think it’s truly a well crafted and amazing movie overall. Good article 🙂

Thank you very much Nof

Thanks for putting this together it was very interesting reading.

Thanks Venus, I appreciate the kind words

Thank you for this critical insight into a film that I need to view again and again. I feel like you nailed it right on the head in that it seemed to miss the mark in some respects the year of its release, but rewards us with a film experience that makes a cozy home in the most remembered films throughtout the ages. This film deserves to be watched again after reading your article. Thanks.

My pleasure Matt.

Thanks, August Merz, for your insights about this classic movie. I appreciate and agree with your conclusion: “…Andy shows that it does no one, least of all yourself, any good to wallow in self-pity and worry, and the best way to prove the wicked wrong is to cultivate goodness.”

You’re welcome Ben.

Really nice, in-depth and insightful article. The first time I saw the movie, I loved it and for me it just gets better every time. It’s a classic in my opinion. Nice work.

I appreciate the kind words Brittany.

Wow I had no idea that this movie flopped when it first came out. That truly amazes me because it is one of the most incredible movies I have ever seen. Anyone who doesn’t find this movie emotionally compelling and moving has to re-watch it.

In the end, it’s always a matter of opinion, but I’d certainly agree that the film is outstanding and worthy of its place in movie history. Thanks for the comment.

“This is a movie that re-enacted its heroes’ escape from imprisonment and came out clean on the other side.” I had really never thought about the film in this way, but wow, that really encapsulates it!

Your reading of Andy and Red’s relationship is really refreshing to me, particularly in your excellent analysis of the significant changes in each of Red’s parole board meetings. Those have always been some of my favorite moments in the film, and your reading of Red’s growth as profoundly influenced by Andy’s steadfast innocence and hope makes me feel the urge to find my DVD and give the film a new look. It’s always been one of my favorites; you’ve just made me appreciate the warm sincerity of this friendship even more. Great work!

I appreciate your kind words kdaley.

Amazing work, August. When strong thought is put into cinema, it becomes something so much more. Film has a way of speaking to us viewers and I don’t believe there is a greater power than that. That is why filmmaking is as powerful as it is. You do a fantastic job digging into the psyche of Andy and Red. You bring out the essence of this film that many individuals do not see. With that being said, Bravo and keep up the good work!

Thanks for the kind words kgbell44.

-August

where there are tyranny and exploitation, there is also a rise of friendship and a group of people who can do anything for you.

Same goes for Andy and Red, where Red fulfills the wishes of Andy, and in return gave Red the hope to go further in life. When there are misery and sorrow among a group there will also be driving forces that would let you overcome that

A good essay. Interesting how the shift to TV increased the film’s popularity.

Shawshank Redemption clearly does not have a cult following. That is normally reserved for lower quality movies, which have a small but devoted (if not weird) following. Shawshank Redemption does not have either of these characteristics.